Abstract

A novel strategy based on metal-free click chemistry was developed for the copper-64 radiolabeling of the core in shell-crosslinked nanoparticles (SCK-NPs). Compared with Cu(I)-catalyzed click chemistry, this metal-free strategy provides the following advantages for Cu-64 labeling of the core of SCK-NPs: (1) elimination of copper exchange between non-radioactive Cu in the catalyst and DOTA-chelated Cu-64; (2) elimination of the internal “click” reactions between the azide and acetylene groups in the same NPs; and (3) increased efficiency of the “click” reaction because water soluble Cu(I) does not need to reach the hydrophobic core of the NPs. When 50 mCi Cu-64 was used for the radiolabeling, the specific activity of the radiolabelled product was 975 Ci/μmol at the end of synthesis, which represents the attachment of ca. 500 Cu-64 atoms per SCK-NP, giving in essence a 500-fold amplification of specific activity of the NP over that of the Cu-64 chelate. To the best of our knowledge, this is the highest specific activity obtained for Cu-64 labeled nanoparticles.

Keywords: Copper-64 radiolabelling, Shell-crosslinked nanoparticles (SCK-NPs), High specific activity, Specific activity amplification, Metal-free click chemistry

Over the past three decades, positron emission tomography (PET) studies with radiolabeled drugs have provided new information on drug uptake, distribution, and various behavioral effects in living animals, and PET also has been used for medical diagnosis of a wide variety of vascular, pulmonary, and metabolic pathologies.1–3 Currently, the vast preponderance of PET radiopharmaceuticals are based on small molecules, but their small sizes limit their functional characteristics. In contrast, nanoparticles (NPs) possess multi-functionality and flexibility of their designs and constitutions that afford a wide range of functional characteristics. NPs comprise the components of the broader vision of “nanomedicine” and can be used as vehicles to detect disease, to deliver therapeutics selectively to diseased tissues, and to monitor progression or regression of disease states.4–6 The broad applicability of NPs takes advantage of their design, which provides both surface areas and internal volumes that serve as sites for derivatization with radionuclides or molecular targeting moieties.7–9 However, a major drawback limiting their wide usage in nuclear imaging up to now is the relatively low radiolabeling specific activity (SA, amount of radioactivity per mass) for nanoparticle-based PET imaging agents although efforts has been made to improve it.10–12 High SA of radiopharmaceuticals is extremely important for PET systems to achieve high-quality images at low dose of radioactivity, and is especially critical for high sensitivity detection of low abundance biomarkers.13 Moreover, high SA helps to ensure the “tracer” phenomenon, in which a very low mass dose of radiopharmaceutical is able to follow the biological pathway without disturbing or disrupting it. Therefore, the development of new methods or agents in order to achieve high specific activity of nanoparticles for PET imaging is a highly desirable goal for both research and clinical purposes.

Shell-crosslinked nanoparticles (SCK-NPs) containing a large variety of functional groups have shown promise for nanomedicine applications.14–18 Generally, SCK-NPs have a micellar structure, with an internal hydrophobic portion comprised of a polystyrene (or other hydrophobic) polymer and a hydrophilic external shell of a poly(acrylic acid-co-acrylamide) (or other hydrophilic) polymer. These block copolymers can self assemble in aqueous solution, and are ultimately stabilized by soluble carbodiimide-mediated crosslinking of some of the acrylates in the exterior shell zone with diamines (e.g., 3,6-dioxa-octane-1,8-diamine, or other compatible crosslinkers). These nanoparticles have demonstrated great potential in drug delivery, and their possible application in PET imaging using radiometals has been previously reported by us.7, 14, 15 Here, we investigate new possibilities for obtaining very high SA radiolabelled nanoparticles.

In recent years, copper-64 (64Cu) has attracted increasing attention as a promising radionuclide due to its suitable decay characteristics (t1/2 12.7 h; β+: 0.653MeV, 17.4%; β−: 0.578 MeV; 39%), as well as the facility and convenience with which it can be used for radiolabeling by coordination with meticulously designed ligands, such as 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetic acid (DOTA), 1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradecane-N′,N″,N‴-tetraacetic acid (TETA) and diacetyl-bis(N4-methylthiosemicarbazone) (ATSM).19–21 The Cu-64 radioisotope can be efficiently produced at high specific activity using biomedical cyclotrons via a (p,n) reaction on isotopically-enriched nickel-64,16 and relevant studies based on Cu-64 radiolabelled biomolecules have demonstrated its great potential in both PET imaging and radiotherapy for detection and treatment of cancers.22–24

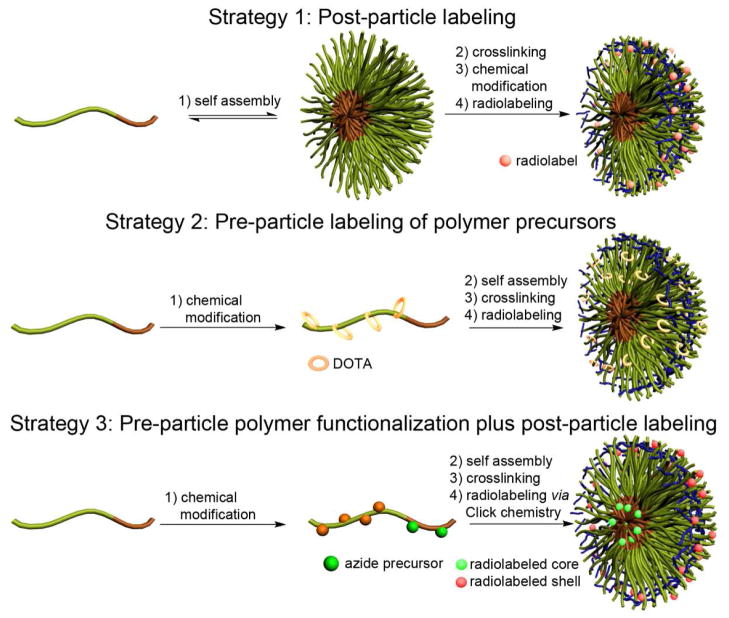

Several strategies have been previously developed to label SCK-NPs with Cu-64: (1) “Post-particle labeling” involved the formation of SCK-NPs followed by the coupling of TETA or DOTA chelators and final complexation with Cu-64 (Scheme 1, strategy 1). This approach afforded SCK-NPs with only tens of radionuclides per nanostructure.7 The low radiolabeling yield was believed to result from inefficiency of the amide-based coupling reaction, which was complicated by electrostatic repulsion between the “empty” chelator and the shell layer; (2) In the “pre-particle labeling” strategy, chelators were coupled to the amphiphilic block copolymers prior to particle assembly (Scheme 1, strategy 2). This approach improved radiolabeling yields by increasing the numbers of available chelators. However, increasing the DOTA chelators per amphiphilic block copolymer, even just from 2 to 4 DOTAs per polymer, changed the assembly processes and altered particle morphologies.25 Therefore, an efficient strategy to prepare radiolabeled nanoparticles with high SA was pursued further.

Scheme 1.

Strategies for radiolabeling of SCK-NPs.

Here, we report development of a novel strategy for Cu-64 labeling of nanoparticles with high SA based on click chemistry (Scheme 1, strategy 3). Our approach takes advantage of the unique structure of the SCK-NPs by functionalizing the shell with alkyne groups that will “click” with targeting groups and functionalizing the core with azide groups for radiolabeling via click chemistry. A distinct advantage of the designed nanoparticles is that the two functional groups, even in the presence of the copper catalyst, cannot interact because they are site-isolated – one is in the core domain and the other is in the shell layer of the nanostructure. This design also enables a single nanoparticle to be labeled either in the interior (core) or on the periphery (shell), or in both places. Different labeling and targeting needs can be accommodated by the choice and sequence of click reactions with alkynes (for the core “click”) and azides (for the shell “click”). In addition, because the Cu-complex is hidden and wrapped in the internal hydrophobic core, dissociation of water-soluble Cu-64 ion is minimized. Therefore, this new approach promises access to much higher specific activity of core-labeled nanoparticles, which is described in detail in the following sections.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Synthesis of SCK-NPs

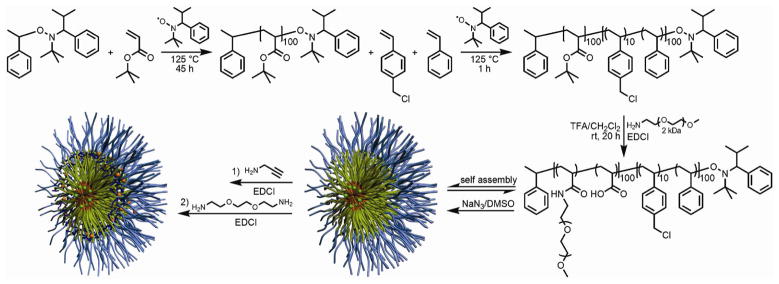

The SCK-NPs used for this study (Scheme 2) were prepared according to procedures modified from our previous report.26 Sequential nitroxide-mediated radical polymerizations were conducted to afford the protected precursor diblock copolymer, poly(tert-butyl acrylate)-b-poly(chloromethylstyrene-co-styrene) (PtBA-b-P(CMS-co-S)). A trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) deprotection followed by amidation reaction of methoxy-terminated PEO2kDa amine afforded a deprotected diblock copolymer, poly(acrylic acid)-g-mPEO2kDa-b-poly(chloromethylstyrene-co-styrene) (PAA-g-mPEO-b-P(CMS-co-S)), which was then self assembled to form core-shell micelles in water. To the micellar solution was added NaN3 in DMSO to introduce the azide functionality onto the micelle cores. A subsequent shell-functionalization reaction was carried out using propargyl amine, 2,2′-(ethylenedioxy)diethylamine and EDCI (1-[3′-(dimethylamino)propyl]-3-ethyl-carbodiimide methiodide) to introduce acetylene functionalities and crosslinks onto the shell domain and to generate shell-crosslinked core/shell “click” ready nanoparticles. In Figure 1, Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) and Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) data showed that the self-assembled micelles and the “click” ready SCK-NPs were spherical, uniform in hydrodynamic diameter as well as in core size. Infrared (IR) analyses of the functionalized SCK-NPs showed availability of the “click” functional groups. The SCK-NPs prepared by this protocol contain ca. 10% azide groups in the core styrene units and 5% acetylene groups in the shell acrylates, with corresponds to ca. 2,500 azides and 1250 acetylenes per NP.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of SCK-NPs containing azides (in the core – green dots) and alkynes (in the shell – red dots).

Figure 1.

a) A representative TEM image of a “click” ready SCK (average diameter = 22 ± 2 nm); b) A representative DLS histogram of a “click” ready SCK (Dint = 120 ± 35 nm, Dvol = 95 ± 15 nm, Dnum = 65 ± 5 nm.

Cu-64 Radiolabelling of SCK-NPs

These SCK-NPs, as prepared above, were suspended in Milli-Q water and stored at room temperature for the radiolabeling. A Cu(I)–catalyzed traditional click chemistry approach was initially attempted. However, several problems were observed (details will be discussed later): (1) copper exchange took place between the non-radioactive Cu in the catalyst and the DOTA-chelated Cu-64; (2) the efficiency of the “click” reaction was low due to difficulties that the water-soluble Cu(I) encountered in trying to reach the hydrophobic core; and (3) activity that became entrapped non-covalently in the particle core, due to the low efficiency of Cu(I)-catalyzed the “click” reaction, subsequently led to significant disassociation of Cu-64 activity from the core of the nanoparticles.

To overcome these problems, we utilized the strain-promoted [3 + 2] azide-alkyne cycloaddition, first reported by and named “metal-free click chemistry” by Bertozzi and coworkers.27 In metal-free click chemistry, the strain of the cyclooctyne system increases its intrinsic reactivity and circumvents the need for copper catalysts. After the original Bertozzi et al. publication describing this approach, several generations of strain-promoted agents were developed by the Bertozzi group, and modified approaches were developed by other groups.28–30 This methodology has seen growing application in various research areas, including drug discovery, materials science, and radiopharmacy,31–33 but as far as we know, it has not been applied to the conjugation of radiolabeled molecules into nanoparticles.

In our approach, DOTA-attached DBCO (dibenzocyclooctyne, the metal-free click moiety) was first radiolabeled with Cu-64, then the purified 64Cu-DOTA-DBCO complex was incubated and “clicked” with azide-containing SCK-NPs without the need for metal catalyst (Scheme 3). This strategy very markedly increased the SA of Cu-64 labeled nanoparticles to 975 Ci/μmol at end of synthesis (EOS), compared with 8.25 Ci/μmol, the SA previously reported for Cu-64 labeled cross-linked iron oxide (CLIO) nanoparticles.34

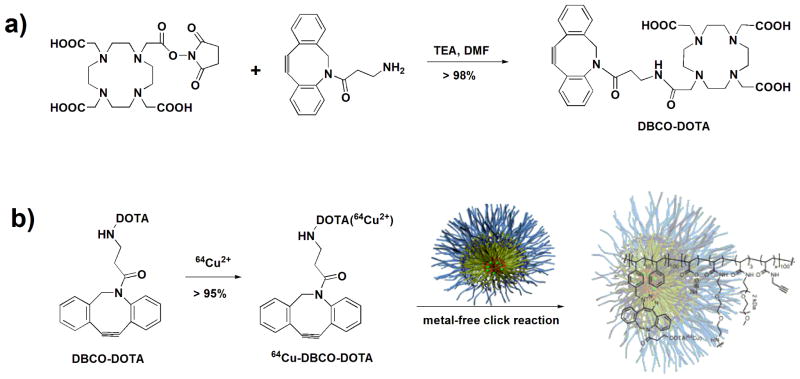

Scheme 3.

a) Synthesis of a DOTA-attached DBCO derivative; b) Radiosynthesis of Cu-64 labeled SCK-NPs.

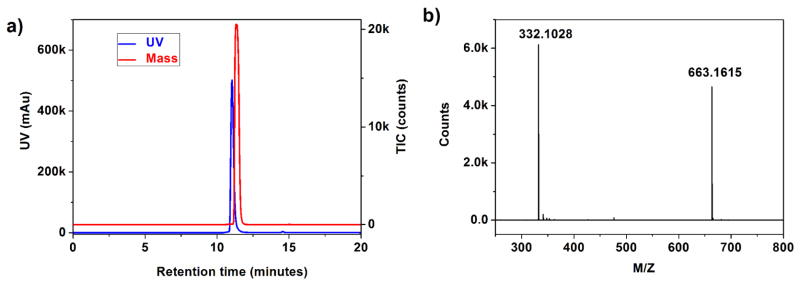

In the first step, the DOTA-conjugated DBCO was synthesized from DOTA-NHS ester and a DBCO primary amine derivative and then purified by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) for subsequent chelating experiments. UV and Total Ion Current (TIC) chromatograms are shown in Figure 2a; the peak at ~11.2 minutes in the mass spectrum (Figure 2b) corresponds to pure DOTA-DBCO, with mass-to-charge (m/z) peak of (M+H+) = 653.1516 and (M+2H+)/2 = 332.1028. After incubating Cu-64 in ammonium acetate buffer solution with a large excess (~50 fold) of DOTA-DBCO at 37 °C for 30 minutes, radiolabeling yields of over 80% were typically obtained, and the Cu-64 complex was purified under optimized HPLC conditions whereby not only could the excess DOTA-DBCO ligand be separated from its Cu2+ complexes, but also could be separated (or partially separated) from DOTA-DBCO complexes (DDCs) formed with some non-radioactive transition metal “contaminants” that are present in cyclotron-produced Cu-64 (such as Fe3+, Ni2+, Zn2+).35 The UV/radioactivity chromatograms are shown in Figure 3a. Therefore, compared with a radiometal labeling protocol lacking an isolation step to remove metal complex impurities, the SA of 64Cu-DOTA-DBCO obtained here was greatly improved and could be as high as 8600 mCi/μmol (decay corrected to bombardment). Subsequently, the identity and separation of these different metal complexes was further confirmed by HPLC chromatography (Figure 3b) obtained under the same conditions used for 64Cu-DOTA-DBCO purification.

Figure 2.

a) UV (blue) and TIC (red) traces of HPLC Chromatography of DOTA-DBCO. The lack of precise peak overlap is due to interdetector flow delay. b) Mass spectrum of the peak at ~11.2 minutes from LC.

Figure 3.

a) Chromatography of the crude Cu2+-DOTA-DBCO complex (DDCs refers to DBCO-DOTA complexes formed with non-radioactive metal contaminants); b) HPLC chromatographies of the DOTA-DBCO complexes with non-radioactive transition metals that may exist in the cyclotron-produced Cu-64 solution.

To isolate the 64Cu-DOTA-DBCO, the corresponding HPLC fraction was collected and concentrated with a Waters Sep-Pak® Light C18 cartridge, and the compound was eluted using 400 μL dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). The chemical identity of purified 64Cu-DOTA-DBCO and its non-radioactive standard were verified by the identical chromatographic elution times of the co-injected species, as well as by the correct m/z of (M+H+) = 724.1102 and (M+2H+)/2 = 362.5740 (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

a) UV (blue) and radio (red) chromatograms for co-injection of 50 μCi 64Cu2+-DOTA-DBCO and 10 μL 50μM non-radioactive standard. The lack of precise peak overlap is due to interdetector flow delay. b) Mass spectrum of peak at ~26.5 minutes from LC.

The next step of the synthesis is the radiolabeling of SCK-NPs, and in this step the metal-free click chemistry demonstrates great advantages over the use of metal catalysts, notably by elimination of exchange between non-radioactive Cu in the catalyst and DOTA-chelated Cu-64 (Table 1). Under the standard Cu(I)-catalyzed click chemistry conditions used to prepare Cu-64 CLIO nanoparticles,36 ~60% of Cu-64 exchange was observed. We have optimized the conditions of this conventional Cu(I)-catalyzed click reaction between the Cu-64 labeled acetylene and the SCK-NP core azides by controlling the stoichiometric ratios, as well as by using a Cu(I) stabilizer, TBTA (tris[(1-benzyl-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methyl]amine). However, even under those conditions, ~10% Cu exchange remained. Fortunately, the metal-free click chemistry protocol completely eliminated Cu exchange since no non-radioactive metal is introduced into the reaction mixtures. Moreover, in the radiolabeling of SCK-NPs, the metal-free click approach (which involves just two-components: SCK-NP and 64Cu-DOTA-DBCO) led to ~64% radiolabeling yields, whereas the Cu(I)-catalyzed click chemistry one (which involves three-components: SCK-NP, 64Cu-DOTA-acetylene, and Cu(I) catalyst) provided only ~10% radiolabeling yield. This suggests that the reason for the low radiolabeling yield of the Cu(I)-catalyzed reaction might be due to insufficient penetration of the water-soluble catalyst Cu(I) into the hydrophobic core of the SCK-NPs. Consequently, the catalyst would not be properly located to catalyze the reaction between the Cu-64 labeled acetylenes that have diffused into the core and the azide functions present in the core. By contrast, the metal-free click approach allows rapid reaction between the 64Cu-DOTA-DBCO and the SCK-NP core azides as soon as the more lipophilic Cu-64 labeled DBCO diffuses into the core.

Table 1.

Cu exchange under Cu(I) catalyzed “click” conditions

| Reported NPs “Click” reaction | Optimized “Click” reaction | |

|---|---|---|

| Acetylene |

(780 μCi) |

(1.0 equiv.) |

| Azide |

(1.0 equiv.) |

(1.0 equiv.) |

| Cu(II) | BPDS*-Cu(II) (2.5 equiv.) |

TBTA-64Cu(II) (carrier-added Cu-64, 1.0 equiv.) |

| Sodium Ascorbate | 25 equiv. | 1.0 equiv. |

| Extent of reaction | ~ 95% | ~ 90% |

| % of Cu exchange | ~ 60% | ~10 % |

BPDS = bathophenanthroline disulfonate sodium salt

We confirmed our hypothesis by radio-iTLC (Instant Thin Layer Chromatography): when the Cu(I)-catalyzed click approach was applied, the SCK-NPs entrapped (rather than clicked with) ~50% of 64Cu-DOTA-acetylene in the core, and this entrapped activity could be gradually extracted out by re-developing the iTLC plate several times. By contrast, using the metal-free approach, we found that less than 5% activity became entrapped in the NP core, since very little activity could be extracted out by re-developing the iTLC plate. Thus, the metal-free approach resulted in durable radiolabeling of the SCK-NP through the highly efficient click reaction between the 64Cu-DOTA-DBCO and azides in the core of SCK-NPs.

Incorporation yield and SA

Incorporation yield and SA are two important parameters for evaluating the quality of any radiosynthesis protocol. However, for a two-step protocol such as the one described here for SCK-NP radiolabeling, it is difficult to achieve high values for both parameters because in the second step, Cu-64-labeled- and unlabeled-nanoparticles cannot be effectively separated. Thus, increasing the concentration or amount of the SCK-NPs may accelerate the reaction of the 64Cu-DOTA-DBCO with the SCK-NPs and result in a higher incorporation yield (% of initial activity incorporated). However, this will be done at the expense of SA (essentially a ratio of labeled to unlabeled NP), because the final labeled product will contain more un-labeled nanoparticles than if smaller starting amounts were used in this radiolabeling step.

The results of initial test experiments in which incorporation yields were determined with a small amount of radioactivity and 8 different amounts of SCK-NPs are summarized in Table 2. When 1 μL of the SCK-NPs solution (0.81mg/mL) was used for the metal–free click reaction with 550 μCi of 64Cu-DOTA-DBCO (SA≈1000mCi/μmol, EOS), ~38 μCi of Cu-64 labeled SCK-NPs was obtained with a SA of 281 Ci/μmol, representing an incorporation yield of only 6.9%. By contrast, if 100 μL of the nanoparticle solution was used, then ~461 μCi of Cu-64 labeled SCK-NPs was obtained, representing an 83.8% incorporation yield, but the SA dropped to 32 Ci/μmol. Therefore, obtaining a sufficient quantity of Cu-64 labeled SCK-NPs for a MicroPET study at a sufficiently high SA would entail the use of a sufficient excess amount of 64Cu-DOTA-DBCO activity to account for the lower incorporation yield. As shown in Table 2, using 25 μL of SCK-NPs solution provided 351 μCi of Cu-64 labeled SCK-NPs with a balanced incorporation yield and SA of 63.8% and 104 Ci/μmol, respectively. Also shown in Table 2 is the number of Cu-64 radionuclides that are incorporated per SCK-NP determined at each SA level, which can be calculated from the factor by which SA becomes amplified by attaching multiple CA-64’s per SCK-NP.

Table 2.

Radiolabeling results of click reaction between 550 μCi purified 64Cu2+-DOTA-DBCO and SCK-NPs containing 10% azide in core, 5% acetylene in shell.

| SCK-NPs (μL) (0.81 mg/mL) |

Incorporation Yield (%) | SA of SCK-NPs (Ci/μmol) | Number of Cu-64 per SCK-NP |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6.9 | 281 | 266 |

| 5 | 20.1 | 162 | 160 |

| 10 | 39.0 | 158 | 150 |

| 25 | 63.8 | 104 | 100 |

| 50 | 69.3 | 56.6 | 54 |

| 100 | 84.0 | 34.1 | 32 |

| 200 | 92.4 | 18.7 | 18 |

| 490 | 98.8 | 8.02 | 8 |

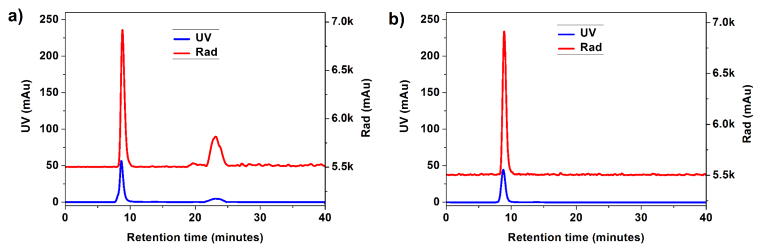

Fast protein liquid chromatography (FPLC) of the crude mixture of radiolabeling via metal-free click chemistry is shown in Figure 5a, in which the labeled NPs eluted at ~7.0 minutes and the un-clicked 64Cu-DOTA-DBCO complex at ~23 minutes. Cu-64-labeled SCK-NPs were purified by passage over a Zeba® desalting column, resulting in the Cu-64-labeled SCK-NPs with over 95% purity, as verified by radio-FPLC (Figure 5b).

Figure 5.

A) FPLC chromatography of 250 μCi of the crude metal-free click mixture before passing over Zeba® desalting column. The lack of precise peak overlap is due to interdetector flow delay. B) FPLC chromatography of 130 μCi of the Cu-64-labeled SCK-NPs after passage over Zeba® desalting column.

Based on these initial studies, 50 mCi of 64Cu was used to further increase the radiolabeling specific activity of both 64Cu-DOTA-DBCO and SCK-NPs.19 After incubating with 250 μL of 1.0 mM DOTA-DBCO for 30 minutes at 40 °C, about 70% radiolabeling yield was obtained with a SA of 1867 mCi/μmol EOS (8600 mCi/μmol at end of bombardment, EOB) as measured by HPLC. After size exclusion purification and C18 Sep-Pak cartridge concentration, elution in 400 μL DMSO gave 20.7 mCi of 64Cu-DOTA-DBCO. Then, 2.0 mL of 10.1 μg/mL SCK-NP in Mill-Q water was added to the 64Cu-DOTA-DBCO DMSO solution, and the mixture was incubated for one hour at 50 °C for radiolabeling. Using this method, we found that ~13% of the 64Cu-DOTA-DBCO was incorporated into the SCK-NPs. The SA of the labeled SCK-NPs was ~975 Ci/μmol at end of synthesis (EOS) and decay correction provided a SA of ~4420 Ci/μmol at end of bombardment. This SA is about 90 fold higher than previously reported 64Cu-CLIO nanoparticles 34 and 6 fold higher than the 64Cu-CANF-Comb37, 38, and ensures the tracer level amounts (10.2 pmol mass for 10 mCi human dose) can be administered for potential clinical studies. The detailed comparison of the SAS of Cu-64 labeled nanoparticles are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Comparison of the SA of the Cu-64 labeled radiotracers.

| SA | 64Cu-DOTA-DBCO | SCK-NPs | CLIO-NPs34 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EOS | EOB | EOS | EOB | EOS | |

| Ci/μmol | ~1.87 | ~8.60 | ~975 | ~4420 | ~11 |

| mCi/mg | ~2800 | ~12800 | ~162 | ~751 | ~8.25 |

A comparison of the EOB specific activities of the 64Cu-DOTA-DBCO precursor (8.6 Ci/μmol) with that of the final Cu-64 labeled SCK-NPs (4420 Ci/μmol) shows a 500-fold increase. Thus, it is apparent that on average ca. 500 precursor molecules have reacted with each NP, which represents reaction of ca. 20% of the azide functions present in the core of the particles. This dramatic “SA amplification” that can be obtained in the labeling of appropriately functionalized SCK-NPs by our copper-free click approach is a clear illustration of the potential value of NP multivalency as an approach to unusual functionality, in this case, remarkably high SA.

CONCLUSION

A novel strategy based on metal-free click chemistry has been developed for radiolabeling of SCK-NPs. Compared with Cu(I)-catalyzed click chemistry, the metal-free strategy improves Cu-64 labeling of the core of the nanoparticles due to the high “click” efficiency even without the metal catalyst usually needed for the click reaction. When 50 mCi of Cu-64 was used for radiolabeling of the SCK-NPs containing 10% in-core azides, very high SA was obtained, up to 975 Ci/μmol (4420 Ci/μmol at EOB). To the best of our knowledge, this is the highest SA value obtained for a Cu-64 core-labeled nanoparticle. More importantly, by increasing the percentage of azides in the core, the SA can potentially be further improved.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

All solvents and reagents were purchased from commercial sources and used without further purification, unless described otherwise. The DBCO-amine was bought from Click Chemistry Tools (Scottsdale, AZ), DOTA-NHS was bought from Macrocyclics (Dallas, TX), chelex@100 resins was obtained from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA), and all other chemicals and reagents were obtained from Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). tert-Butyl acrylate (tBA), 4-vinyl benzylchloride and styrene were filtered through a plug of aluminum oxide to remove the inhibitor. The universal alkoxyamine initiator 2,2,5-trimethyl-3-(1′-phenylethoxy)-4-phenyl-3-azahexane and the corresponding nitroxide 2,2,5-trimethyl-4-phenyl-3-azahexane-3-nitroxide were synthesized according to the literature method.39 All reactions were performed under N2, unless otherwise noted. De-ionized water (DI-H2O) was produced using a Millipore Milli-Q water system. 64Cu2+ in 0.1M HCl was produced at Washington University School of Medicine and obtained through the Radionuclide Resource for Cancer Applications.

Instrumentation

1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were recorded at 500 MHz and 125 MHz, respectively, as solutions with the solvent proton or carbon signal as a standard. HR-ESI-MS were measured on Waters LCT-premier XE LC-MS station. IR spectra of neat films on NaCl plates were recorded using a Shimadzu Prestige21 IR spectrometer. A GE (ÄKTA) fast protein liquid chromatography (FPLC) apparatus was used for analysis of the final Cu-64 labeled SCK-NPs. The C18(2) Luna HPLC column and SEC Superose FPLC column were purchased from phenomenex (Torrance, CA) and GE (Piscataway, NJ)respectively. Zeba® desalting columns used to purify the Cu-64 labeled SCK-NPs were bought from Thermo-scientific (Rockford, IL). Hewlett-Packard model 1050 high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) apparatus was used for purifying synthesized and labeled compounds. LC-MS spectra were obtained with a Waters LC-MS API-3000 spectrometer. The two elution buffers (0.1 v% TFA in de-ionized water as elution buffer A and 0.1 v% TFA in acetonitrile as elution buffer B) were used for both HPLC and LC-MS.

Gel permeation chromatography (GPC) was conducted on a Waters 1515 HPLC (Waters Chromatography, Inc. in Milford, MA) equipped with a Waters 2414 differential refractometer, a PD2020 dual-angle (15° and 90°) light scattering detector (Precision Detectors, Inc. in Bellingham, MA), and a three-column series PL gel 5μm Mixed C, 500 Å, and 104 Å, 300 × 7.5 mm columns (Polymer Laboratories, Inc. in Amherst, MA). The system was equilibrated at 35 °C in anhydrous tetrahydrofuran (THF), which served as the polymer solvent and eluent with a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. Polymer solutions were prepared at a known concentration (ca. 4 mg/mL – 5 mg/mL) and an injection volume of 200 μL was used. Data collection and analysis were performed, respectively, with Precision Acquire software and Discovery 32 software (Precision Detectors, Inc.). Interdetector delay volume and the light scattering detector calibration constant were determined by calibration using a nearly monodispersed polystyrene standard (Pressure Chemical Co. (Pittsburgh, PA), Mp = 90 kDa, Mw/Mn < 1.04). The differential refractometer was calibrated with standard polystyrene reference material (SRM 706 NIST), of known specific refractive index increment dn/dc (0.184 mL/g). The dn/dc values of the analyzed polymers were then determined from the differential refractometer response.

Dynamic light scattering measurements were conducted with a Brookhaven Instruments Company (Holtsville, NY) DLS system equipped with a model BI-200SM goniometer, BI-9000AT digital correlator, and a model EMI-9865 photomultiplier, and a model Innova 300 Ar ion laser operated at 514.5 nm (Coherent Inc., Santa Clara, CA). Measurements were made at 25 ± 1 °C. Prior to analysis, solutions were filtered through a 0.45 μm Millex®-GV PVDF membrane filter (Millipore Corp., Medford, MA) to remove dust particles. Scattered light was collected at a fixed angle of 90°. The digital correlator was operated with 522 ratio spaced channels, an initial delay of 5 μs, a final delay of 50 ms, and a duration of 8 minutes. A photomultiplier aperture of 400 μm was used, and the incident laser intensity was adjusted to obtain a photon counting of between 200 and 300 kcps. The calculations of the particle size distributions and distribution averages were performed with the ISDA software package (Brookhaven Instruments Company, Holtsville, NY), which employed single-exponential fitting, Cumulants analysis, and CONTIN particle size distribution analysis routines. All determinations were average values from ten measurements. DLS measurements were also conducted using Delsa Nano C from Beckman Coulter, Inc. (Fullerton, CA) equipped with a laser diode operating at 658 nm. Size measurements were made in nanopure water. Scattered light was detected at 15° angle and analyzed using a log correlator over 70 accumulations for a 0.5 mL of sample in a glass size cell (0.9 mL capacity). The photomultiplier aperture and the attenuator were automatically adjusted to obtain a photon counting rate of ca. 10 kcps. The calculation of the particle size distribution and distribution averages was performed using CONTIN particle size distribution analysis routines using Delsa Nano 2.31 software. The peak average of histograms from intensity, volume and number distributions out of 70 accumulations was reported as the average diameter of the particles.

TEM bright-field imaging was conducted on a Hitachi H-7500 microscope, operating at 80 kV. The samples were prepared as follows: 4 μL of the dilute solution (with a polymer concentration of ca. 0.2 – 0.5 mg/mL) was deposited onto a carbon-coated copper grid, which was pre-treated with absolute ethanol to increase the surface hydrophilicity. After 5 min, the excess of the solution was quickly wicked away by a piece of filter paper. Samples were then negatively stained with 4 μL of 1 wt% phosphotungstic acid (PTA) aqueous solution. After 1 min, the excess PTA solution was quickly wicked away by a piece of filter paper and the samples were left to dry under ambient conditions overnight.

Synthesis of poly(tert-butyl acrylate)100 (PtBA)100 (I)

To a flame-dried 50-mL Schlenk flask equipped with a magnetic stir bar and under N2 atmosphere, at room temperature (rt), was added 2,2,5-trimethyl-3-(1′-phenylethoxy)-4-phenyl-3-azahexane (635 mg, 1.95 mmol), 2,2,5-trimethyl-4-phenyl-3-azahexane-3-nitroxide (21.0 mg, 0.0975 mmol), and tert-butyl acrylate (40.0 g, 312 mmol). The reaction flask was sealed and stirred for 10 min at rt. The reaction mixture was degassed through three cycles of freeze-pump-thaw. After the last cycle, the reaction mixture was recovered back to rt and stirred for 10 min before being immersed into a pre-heated oil bath at 125 °C to start the polymerization. After 45 h, 1H NMR analysis showed 63% monomer conversion had been reached. The polymerization was quenched by quick immersion of the reaction flask into liquid N2. The reaction mixture was dissolved in THF and precipitated into H2O/MeOH (v:v, 1:4) three times to afford PtBA as a white powder (20.0 g, 76% yield based upon monomer conversion); MnNMR = 15,900 g/mol, MnGPC = 14,900 g/mol, Mw/Mn = 1.05. 1H NMR (CD2Cl2, ppm): δ 1.43 (br, 1290 H), 1.80 (br, 70 H), 2.21 (br, 160 H), 7.14–7.26 (m, 10 H). 13C NMR (CD2Cl2, ppm): δ 28.4, 36.5, 38.0, 42.5, 80.9, 174.4.

Synthesis of poly(tert-butyl acrylate)100-b-poly(chloromethylstyrene10-co-styrene90)100 (PtBA100-b-P(CMS10-co-S90)100) (II)

To a flame-dried 50-mL Schlenk flask equipped with a magnetic stir bar and under N2 atmosphere, at rt, was added I (3.00 g, 0.233 mmol), 2,2,5-trimethyl-4-phenyl-3-azahexane-3-nitroxide (2.05 mg, 9.00 μmol), 4-chloromethyl styrene (1.425 g, 9.34 mmol) and styrene (8.75 g, 84.1 mmol). The reaction flask was sealed and stirred for 10 min at rt. The reaction mixture was degassed through three cycles of freeze-pump-thaw. After the last cycle, the reaction mixture was recovered back to rt and stirred for 10 min before being immersed into a pre-heated oil bath at 125 °C to start the polymerization. After 1.3 h, 1H NMR analysis showed 25% monomer conversion had been reached. The polymerization was quenched by quick immersion of the reaction flask into liquid N2. The reaction mixture was dissolved in THF and precipitated into H2O/MeOH (v:v, 1:4) three times to afford PtBA-b-P(CMS-co-S) as a white powder, (4.65 g, 93% yield based upon monomer conversion); MnNMR = 27,500 g/mol, MnGPC = 26,000 g/mol, Mw/Mn = 1.13. 1H NMR (CD2Cl2, ppm): δ 1.43 (br, 1183 H), 1.80 (br, 118 H), 2.21 (br, 100 H), 4.53 (br, 20 H), 6.36–6.82 (m, 168 H), 7.14–7.26 (m, 254 H). 13C NMR (CD2Cl2, ppm): δ 21.5, 28.4, 36.5, 38.0, 40.5, 42.6, 80.9, 121.8, 128.9, 143.0, 149.4, 169.7, 174.7.

Synthesis of poly(acrylic acid)100-b-poly(chloromethylstyrene10-co-styrene90)100 (PAA100-b-P(CMS10-co-S90)100) (III)

To a 50-mL round bottom flask equipped with a magnetic stir bar, was added II (3.04 g, 128 μmol), trifluoroacetic acid (7.28 g, 63.9 mmol) and dichloromethane (30.0 mL). The reaction mixture was allowed to stir for 14 h at rt. Excess acid was removed under vacuum. The residue was dissolved into 10 mL of THF and precipitated into hexanes three times to afford III as a white powder (2.6 g, 87% yield). MnNMR = 22,000 g/mol. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, ppm): δ 1.80 (br, 110 H), 2.21 (br, 100 H), 4.53 (br, 10 H), 6.36–6.82 (m, 180 H), 7.14–7.26 (m, 290 H), 12.3 (br, 98 H). 13C NMR (CD2Cl2, ppm): δ 36.2, 38.0, 40.5, 42.6, 80.9, 121.8, 128.9, 143.0, 149.4, 169.7, 174.6.

Synthesis of poly(acrylic acid)100-g-(CONH-PEO2kDa-OCH3)-b-poly(chloromethylstyrene10-co-styrene90)100 (PAA100-g-mPEO2kDa-b-P(CMS10-co-S90)100) (IV)

A flame-dried 100-mL round bottom flask equipped with a magnetic stir bar was charged with III (438 mg, 19.9 μmol) and 50 mL of dry DMF. To the stirred solution, 1-hydroxybenzotrizole hydrate (HOBt) (91.2 mg, 0.675 mmol) and EDCI (201 mg, 0.675 mmol) were added and the reaction was left to proceed for 1 h, after which a solution of NH2-mPEO2kDa (667 mg, 0.334 mmol, 16.8 equiv) dissolved in 5 mL of DMF and N,N-diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA) (87.2 mg, 0.675 mmol) were added. The reaction mixture was further stirred for 20 h at room temperature before being transferred to a presoaked dialysis tubing (MWCO ca. 6000 – 8000 Da), and dialyzed against nanopure H2O for 2 days, to remove all of the impurities and afford PAA100-g-mPEO2kDa-b-P(CMS10-co-S90)100 (IV) as a white solid after lyophilization (913 mg, 92% yield). MnNMR = 28,000 g/mol. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, ppm): δ 12.3 (br, 95 H), 8.94 (br, 78 H), 7.22 (m, 10 H), 6.45 (br, 200 H), 3.50 - 3.40 (br, 280 H), 2.40 - 2.18 (br, 45 H), 1.37 (m, 240 H).

General procedure for self assembly of PAA100-g-mPEO2kDa-b-P(CMS10-co-S90)100 block copolymers

PAA100-g-mPEO2kDa-b-P(CMS10-co-S90)100 (ca. 25.0 mg) polymer was dissolved in DMF (25.0 mL) in a 100 mL round bottom flask and allowed to stir for 1 h at rt. To this solution, an equal volume of nanopure water (25.0 mL) was added dropwise via a syringe pump over a period of 3 h. The reaction mixture was allowed to stir for additional 12 h at rt and dialyzed against nanopure water for 1 day in a presoaked dialysis tubing (MWCO ca. 6 – 8 kDa) to afford a micelle solution with a final polymer concentration of ca. 0.25 mg/mL.

General procedure for core functionalization to afford micelles of PAA100-g-mPEO2kDa-b-P(AMS10-co-S90)100

To a 50-mL RB flask equipped with a magnetic stir bar was added a solution of IV micelles in nanopure H2O. To this solution, was added sodium azide dissolved in DMSO (200 molar eq. relative to the chloromethylstyrene residues). The reaction mixture was allowed to stir at rt for 24 h. The reaction mixture was transferred to pre-soaked dialysis tubing (MWCO ca. 3,500 Da) and dialyzed against nanopure water for 2 d to remove excess small molecule starting materials and by-products, and afford aqueous solutions of micelles. IR (lyophilized dry powder, KBr): 3600-3250, 3000-2850, 2097, 1695, 1557, 1502, 1495, 753, 700 cm−1.

General procedure for shell functionalization to afford micelles of poly(acrylic acid-co-propynyl amide)100-g-(CONH-PEO2kDa-OCH3)-b-poly(azidomethylstyrene-co-styrene)100 (P(AA-co-PA)100-g-mPEO2kDa-b-P(AMS-co-S)100)

To a 50-mL RB flask equipped with a magnetic stir bar was added a solution of IV micelles in nanopure H2O. To this solution was added propargyl amine dissolved in nanopure H2O (5.5 mol% relative to the acrylic acid residues). To this solution was added, dropwise via a syringe pump over 1 h, a solution of 1-[3′-(dimethylamino)propyl]-3-ethylcarbodiimide methiodide (EDCI) (7 mol% relative to the acrylic acid residues) and the reaction mixture was further stirred at rt for 24 h. Finally, the reaction mixture was transferred to pre-soaked dialysis tubing (MWCO ca. 3,500 Da) and dialyzed against nanopure water for 2 d to remove excess small molecule starting materials and byproducts, and afford aqueous solutions of micelles. IR (lyophilized dry powder, KBr): 3600-3250, 3000-2850, 2122, 2099, 1680, 1557, 1502, 1495, 753, 700, 630 cm−1.

General procedure for shell crosslinking of micelles P(AA-co-PA)100-g-mPEO2kDa-b-P(AMS-co-S)-100

To a 50-mL RB flask equipped with a magnetic stir bar was added a solution of micelles in nanopure H2O. To this solution was added a solution of 2,2′-(ethylenedioxy)diethylamine (11 mol% relative to the acrylic acid residues) for 20% nominal crosslinking extent. The reaction mixture was allowed to stir at rt for 2 h. To this solution was added, dropwise via a syringe pump over 1 h, a solution of 1-[3′-(dimethylamino)propyl]-3-ethylcarbodiimide methiodide (EDCI) (28 mol% relative to the acrylic acid residues) and the reaction mixture was stirred at rt for another 16 h. Finally, the reaction mixture was transferred to pre-soaked dialysis tubing (MWCO ca. 3,500 Da) and dialyzed against nanopure water for 2 d to remove the non-attached crosslinker, excess small molecule starting materials and by-products, and to afford aqueous solutions of shell-crosslinked spherical nanoparticles (SCK-NPs). SCK-NPs measured 33 ± 3 nm by number-average distribution dynamic light scattering measurements and 22 ± 2 nm in diameter, by TEM.

Synthesis of DOTA-DBCO ligand

A 5-mL conical self-standing vial equipped with a magnetic stir bar was charged with DBCO-amine (5.0 mg, 18.0 μmol), triethylamine (TEA, 28 μL 200 μmol) and dry DMF (1.0 mL). To the stirred solution, DOTA-NHS (15.0 mg, 20 μmol) was added. After the reaction mixture was stirred for 3 h, more than 98% DBCO-amine converted to DBCO-DOTA lignd, and then 500 μL of H2O was added to hydrolyze the excess DOTA-NHS ester for 0.5 h. The solvent was then removed under vacuum, and the residue was re-dissolved in 2 mL of 20% acetonitrile. Purification of DOTA-DBCO was performed using Phenomenex Luna C18(2) (250* 10 mm) column with the following gradient conditions (3.0 mL/minute flow rate; 0–5 minutes 70% A, 5–25 minutes 70% A to 30% A, 25–30 minutes 30% A to 10% A), and under this condition, the DOTA-DBCO was eluted out at ~10.5 minutes. The identity and purity of the purified DOTA-DBCO was confirmed by LC-MS using an Phenomenex Luna C18(2) (150*4.6 mm) column with the following gradient conditions (1.0 mL/minute flow rate; 0–5 minutes 100% A, 5–20 minutes 100% A to 10% A, 25–30 minutes 10% A). The UV chromatogram and TIC chromatogram of LC-MS are shown in Figure 2a, and the mass spectrum of the peak at ~11.2 minutes is shown in Figure 2b. It was confirmed that the peak at ~11.2 minutes corresponds to pure DOTA-DBCO by mass spectrum. (HR-ESI-MS, calculated, m/z (M+H)+, 663.3142; observed, m/z (M+H)+ = 663.3151, (M+2H+)/2 = 332.1614.)

Removing trace metal contamination from the radiometal labeling

Before experiments of radiometal labeling, reagents and vessels used must be free from trace metals contamination according to modifications of a previously reported protocol.40 To remove trace metal contaminants from reaction tubes, caps and pipette tips: 1) Soak the tubes, caps and/or tips in 2.0 M nitric acid (diluted from concentrated nitric acid with Milli-Q H2O) overnight with periodic mixing, and then drain; 2) Wash with absolute ethanol and then drain; 3) Wash with diethyl ether (for drying) and then drain; 4) Dry at room temperature under moderate nitrogen flow overnight. To remove trace metal contaminants from reaction buffers, HPLC elution buffer and other solutions: 1) Add Chelex resin (10 g/L) to the buffers and solutions; 2) Stir over night at room temperature; 3) Filter through a Corning 1-liter filter system (pore size 0.2 mm).

Preparation of 64Cu2+-DOTA-DBCO complex

1.0 mM DOTA-DBCO stock solution was prepared in 10 mM NH4OAc (pH = 6.50) buffer and used for Cu-64 labeling without further dilution. Cyclotron-produced 64Cu2+ (50 mCi at EOB, in 0.1M HCl) was diluted with 0.1 M NH4OAc (pH = 6.80) until the 64Cu2+ (pH ~ 5.50–6.00) solution with specific activity of 200 μCi/μL (decay corrected to EOB) was obtained. The DOTA-DBCO stock solution was mixed with the Cu-64 solution in the ratio 1: 2 (v: v) and the mixture incubated at 37–40 °C. Normally, more than 95% radiolabeling yield could be achieved after 30 minutes, and the 64Cu2+-DOTA-DBCO was purified by HPLC using an Phenomenex Luna C18(2) (150*4.6 mm) column with the isocratic elution (1.5 mL/minute flow rate and 20% A), and the chromatography was shown in Figure 3a. The corresponding peak was separated and collected, and then concentrated with Waters C18 Sep-Pak and eluted in 400 μL DMSO. Its identity and purity was confirmed by the co-injection on radio-HPLC with non-radioactive standard under the same HPLC condition used for the 64Cu2+-DOTA-DBCO purification (Figure 4a and 4b). The UV peak at ~26.5 minutes in the mass spectrum corresponds to the pure Cu-DOTA-DBCO complex (HR-ESI-MS, calculated, m/z (M+H)+ = 724.2282; observed, m/z (M+H)+ = 724.2289, (M+2H+/)2= 362.6136). SA of the 64Cu2+-DOTA-DBCO was determined by dividing the activity of 64Cu2+-DOTA-DBCO complex by the corresponding mass calculated from the UV peak of HPLC.

General radiolabeling procedures of SCK-NPs via the metal-free click reaction

Initial experiments were conducted with small amounts (10 μL, ~550 μCi) of 64Cu2+-DOTA-DBCO and different amounts of SCK-NPs stock solution (0.81 mg/mL, 10% azide in core, 5% acetylene in shell) diluted to 490 μL with Milli-Q water (see Table 2). After the reaction mixture was incubated for 30 minutes at 37 °C, the extent of reaction were determined with radio-iTLC. A 1 μL aliquot of product was spotted onto a radio-iTLC plate and developed using a mobile phase of 0.1 M sodium bicarbonate. After being developed, the radio-iTLC plate was then counted using the Bioscan (Washington, DC) radio-TLC scanner to quantify 64Cu2+-DOTA-DBCO complex (Rf = 0.80) and SCK-NPs “clicked” complex (Rf = 0.0). The radiolabeling yields were calculated by dividing the area of the origin radioactivity peak (Rf = 0.0, SCK-NPs “clicked” complex) by the total area of the radioactivity peaks. The Cu-64-incorporated SCK-NPs were purified by passage over a Zeba® desalting column. The identity and purity of the collected fraction was confirmed by radio-FPLC using GE Superose (10/300 GL) Column with the isocratic elution (0.8 mL/minute flow rate; 100% HEPES buffer (0.1M, pH=4.50)), as shown in Figure 5b. The peak (at ~ 23.5 minutes, in Figure 5a) of 64Cu2+-DOTA-DBCO was removed by passage over a Zeba® desalting column, and the purity of 64Cu2+-DOTA-DBCO “clicked” SCK-NPs was ≥ 95% as shown in Figure 5b. The SA of the 64Cu2+-DOTA-DBCO “clicked” SCK-NPs was calculated described as below.

General procedure to calculate the SA of the Cu-64-incorporated SCK-NPs

The SA was obtained by dividing the activity of SCK-NPs “clicked” with 64Cu2+-DOTA-DBCO by the total mass of SCK-NPs in the format of either mCi/mg or Ci/μmol. The activity of SCK-NPs “clicked” with 64Cu2+-DOTA-DBCO = total activity used for the reaction * labeling yield determined by iTLC (and/or FPLC); the total mass of SCK-NPs (mg) = density of SCK-NPs * total volume of SCK-NPs used for the labeling; and the total quantity of SCK-NPs (μmol) = the total mass of SCK-NPs (mg)*1000/average molecular weight of SCK-NPs.

The scaled up radiolabeling experiment

Preparation of 64Cu2+-DOTA-DBCO was conducted as described in the earlier section with 50mCi 64Cu and produced 20.7 mCi of 64Cu2+-DOTA-DBCO in 0.4 mL of DMSO with the SA of 1867 mCi/μmol at EOS (8600 mCi/μmol at EOB). 25 μL of the SCK-NPs solution was mixed with 2.0 mL Milli-Q water and added to the 64Cu2+-DOTA-DBCO solution (20.7 mCi, 0.4 mL) in DMSO. The reaction mixture was incubated for one hour at 40°C to give a ~10% 64Cu2+-DOTA-DBCO incorporation yield, and then another hour at 50°C, which increased the incorporation yield to ~13%. The SA of labeled SCK-NPs was ~975 Ci/μmol at EOS and decay corrected to ~4420 Ci/μmol (EOB).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for funding support from the Office of Science (BER), US Dept. of Energy, Grant No. ER64671. We also thank the cyclotron crew of the Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology, Washington University School of Medicine for their support in the production of radioisotopes. N. Lee thanks GlaxoSmithKline for their financial support through an ACS Division of Organic Chemistry Graduate Fellowship. This work was also supported in part by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health as a Program of Excellence in Nanotechnology (HHSN268201000046C) and by the Welch Foundation through the W. T. Doherty-Welch Chair in Chemistry, Grant No. A-0001. The authors thank the Department of Otolaryngology, Washington University School of Medicine for access to the TEM, and the Molecular Imaging Laboratory, University of Pittsburgh Medical School for access to Waters LCT-premier XE LC-MS station. The authors thank Drs. W. Edwards and J. Dence for discussion and editing.

References

- 1.Bonardel G, Lecoules S, Mantzarides M, Carmoi T, Gontier E, Blade JS, Soret M, Foehrenbach H, Algayres JP. Positron Emission Tomography in Internal Medicine. Presse Med. 2008;37:460–469. doi: 10.1016/j.lpm.2007.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goh AS, Ng DC. Clinical Positron Emission Tomography Imaging--Current Applications. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2003;32:507–517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Welch MJ, Mathias CJ, McGuire A. Positron Emission Tomography. Present Status and Future Prospectives. Acta Radiol Suppl. 1991;376:24–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perry JL, Herlihy KP, Napier ME, Desimone JM. PRINT: A Novel Platform Toward Shape and Size Specific Nanoparticle Theranostics. Acc Chem Res. 2011;44:990–998. doi: 10.1021/ar2000315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crombez L, Morris MC, Deshayes S, Heitz F, Divita G. Peptide-based Nanoparticle for ex vivo and in vivo Drug Delivery. Curr Pharm Des. 2008;14:3656–3665. doi: 10.2174/138161208786898842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen L, Nakano K, Kimura S, Matoba T, Iwata E, Miyagawa M, Tsujimoto H, Nagaoka K, Kishimoto J, Sunagawa K, et al. Nanoparticle-mediated Delivery of Pitavastatin into Lungs Ameliorates the Development and Induces Regression of Monocrotaline-Induced Pulmonary Artery Hypertension. Hypertension. 2011;57:343–350. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.157032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sun X, Rossin R, Turner JL, Becker ML, Joralemon MJ, Welch MJ, Wooley KL. An Assessment of the Effects of Shell Cross-Linked Nanoparticle Size, Core Composition, and Surface PEGylation on in vivo Biodistribution. Biomacromolecules. 2005;6:2541–2554. doi: 10.1021/bm050260e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Welch MJ, Hawker CJ, Wooley KL. The Advantages of Nanoparticles for PET. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:1743–1746. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.061846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Montet X, Montet-Abou K, Reynolds F, Weissleder R, Josephson L. Nanoparticle Imaging of Integrins on Tumor Cells. Neoplasia. 2006;8:214–222. doi: 10.1593/neo.05769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jarrett BR, Gustafsson B, Kukis DL, Louie AY. Synthesis of 64Cu-labeled Magnetic Nanoparticles for Multimodal Imaging. Bioconjug Chem. 2008;19:1496–504. doi: 10.1021/bc800108v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andreozzi E, Seo JW, Ferrara K, Louie A. Novel Method to Label Solid Lipid Nanoparticles with 64Cu for Positron Emission Tomography Imaging. Bioconjug Chem. 2011;22:808–18. doi: 10.1021/bc100478k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schipper ML, Iyer G, Koh AL, Cheng Z, Ebenstein Y, Aharoni A, Keren S, Bentolila LA, Li J, Rao J, et al. Particle Size, Surface Coating, and PEGylation Influence the Biodistribution of Quantum Dots in Living Mice. Small. 2009;5:126–34. doi: 10.1002/smll.200800003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jagoda EM, Vaquero JJ, Seidel J, Green MV, Eckelman WC. Experiment Assessment of Mass Effects in the Rat: Implications for Small Animal PET Imaging. Nucl Med Biol. 2004;31:771–779. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2004.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rossin R, Pan D, Qi K, Turner JL, Sun X, Wooley KL, Welch MJ. 64Cu-labeled Folate-Conjugated Shell Cross-Linked Nanoparticles for Tumor Imaging and Radiotherapy: Synthesis, Radiolabeling, and Biologic Evaluation. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:1210–1218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li Y, Hindi K, Watts KM, Taylor JB, Zhang K, Li Z, Hunstad DA, Cannon CL, Youngs WJ, Wooley KL. Shell Crosslinked Nanoparticles Carrying Silver Antimicrobials as Therapeutics. Chem Commun. 2010;46:121–123. doi: 10.1039/b916559b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang K, Fang H, Wang Z, Li Z, Taylor JS, Wooley KL. Structure-Activity Relationships of Cationic Shell-Crosslinked Knedel-Like Nanoparticles: Shell Composition and Transfection Efficiency/Cytotoxicity. Biomaterials. 2010;31:1805–1813. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.10.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang K, Fang H, Shen G, Taylor JS, Wooley KL. Well-Defined Cationic Shell Crosslinked Nanoparticles for Efficient Delivery of DNA or Peptide Nucleic Acids. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2009;6:450–457. doi: 10.1513/pats.200902-010AW. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu J, Sun G, Rossin R, Hagooly A, Li Z, Fukukawa KI, Messmore BW, Moore DA, Welch MJ, Hawker CJ, et al. Labeling of Polymer Nanostructures for Medical Imaging: Importance of Crosslinking Extent, Spacer Length, and Charge Density. Macromolecules. 2007;40:2971–2973. doi: 10.1021/ma070267j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCarthy DW, Shefer RE, Klinkowstein RE, Bass LA, Margeneau WH, Cutler CS, Anderson CJ, Welch MJ. Efficient Production of High Specific Activity 64Cu Using A Biomedical Cyclotron. Nucl Med Biol. 1997;24:35–43. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(96)00157-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lewis JS, Welch MJ, Tang L. Workshop on the Production, Application and Clinical Translation of “Non-standard” PET Nuclides: A Meeting Report. Q J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008;52:101–106. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dehdashti F, Grigsby PW, Mintun MA, Lewis JS, Siegel BA, Welch MJ. Assessing Tumor Hypoxia in Cervical Cancer by Positron Emission Tomography with 60Cu-ATSM: Relationship to Therapeutic Response-A Preliminary Report. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;55:1233–1238. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)04477-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li WP, Lewis JS, Kim J, Bugaj JE, Johnson MA, Erion JL, Anderson CJ. DOTA-D-Tyr(1)-Octreotate: A Somatostatin Analogue for Labeling with Metal and Halogen Radionuclides for Cancer Imaging and Therapy. Bioconjug Chem. 2002;13:721–728. doi: 10.1021/bc015590k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tian X, Chakrabarti A, Amirkhanov NV, Aruva MR, Zhang K, Mathew B, Cardi C, Qin W, Sauter ER, Thakur ML, et al. External Imaging of CCND1, MYC, and KRAS Oncogene mRNAs with Tumor-targeted Radionuclide-PNA-Peptide Chimeras. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1059:106–144. doi: 10.1196/annals.1339.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Connett JM, Buettner TL, Anderson CJ. Maximum Tolerated Dose and Large Tumor Radioimmunotherapy Studies of 64Cu-labeled Monoclonal Antibody 1A3 in A Colon Cancer Model. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:3207s–3212s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Welch MJ, Sun G, Xu J, Hagooly A, Rossin R, Li Z, Moore DA, Hawker CJ, Wooley KL. Strategies for Optimized Radiolabeling of Nanoparticles for in vivo PET Imaging. Adv Mater. 2007;19:3157–3162. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wooley KL, O’Reilly RK, Joralemon MJ, Hawker CJ. Functionalization of Micelles and Shell Cross-Linked Nanoparticles Using Click Chemistry. Chem Mater. 2005;17:5976–5988. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Agard NJ, Prescher JA, Bertozzi CR. A Strain-promoted [3 + 2] Azide-alkyne Cycloaddition for Covalent Modification of Biomolecules in Living Systems. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:15046–15047. doi: 10.1021/ja044996f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Codelli JA, Baskin JM, Agard NJ, Bertozzi CR. Second-Generation Difluorinated Cyclooctynes for Copper-free Click Chemistry. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:11486–11493. doi: 10.1021/ja803086r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jewett JC, Sletten EM, Bertozzi CR. Rapid Cu-free Click Chemistry with Readily Synthesized Biarylazacyclooctynones. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:3688–3690. doi: 10.1021/ja100014q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boons GJ, Ning XH, Guo J, Wolfert MA. Visualizing Metabolically Labeled Glycoconjugates of Living Cells by Copper-free and Fast Huisgen Cycloadditions. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2008;47:2253–2255. doi: 10.1002/anie.200705456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yim CB, Dijkgraaf I, Merkx R, Versluis C, Eek A, Mulder GE, Rijkers DT, Boerman OC, Liskamp RM. Synthesis of DOTA-Conjugated Multimeric [Tyr3]octreotide Peptides via A Combination of Cu(I)-Catalyzed “Click” Cycloaddition and Thio Acid/Sulfonyl Azide “Sulfo-Cick” Amidation and Their in vivo Evaluation. J Med Chem. 2010;53:3944–3953. doi: 10.1021/jm100246m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rijkers DT, Merkx R, Yim CB, Brouwer AJ, Liskamp RM. ‘Sulfo-click’ for Ligation as well as for Site-specific Conjugation with Peptides, Fuorophores, and Metal Chelators. J Pept Sci. 2010;16:1–5. doi: 10.1002/psc.1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laughlin ST, Agard NJ, Baskin JM, Carrico IS, Chang PV, Ganguli AS, Hangauer MJ, Lo A, Prescher JA, Bertozzi CR. Metabolic Labeling of Glycans with Azido Sugars for Visualization and Glycoproteomics. Methods Enzymol. 2006;415:230–250. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)15015-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nahrendorf M, Keliher E, Marinelli B, Waterman P, Feruglio PF, Fexon L, Pivovarov M, Swirski FK, Pittet MJ, Vinegoni C, et al. Hybrid PET-Optical Imaging Using Targeted Probes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:7910–7915. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0915163107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carey P, Liu Y, Kume M, Lapi S, Welch MJ. The Production of High Specific Activity Cu-64 as Measured by Ion Chromatography. J Nucl Med. 2010;(Supplement 2):1552. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nahrendorf M, Zhang H, Hembrador S, Panizzi P, Sosnovik DE, Aikawa E, Libby P, Swirski FK, Weissleder R. Nanoparticle PET-CT Imaging of Macrophages in Inflammatory Atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2008;117:379–387. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.741181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu Y, Pressly ED, Abendschein DR, Hawker CJ, Woodard GE, Woodard PK, Welch MJ. Targeting Angiogenesis Using A C-Type Atrial Natriuretic Factor-Conjugated Nanoprobe and PET. J Nucl Med. 2011;52:1956–63. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.089581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu Y, Welch MJ. Nanoparticles Labeled with Positron Emitting Nuclides: Advantages, Methods, and Applications. Bioconjug Chem. 2012 doi: 10.1021/bc200264c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Benoit D, Chaplinski V, Braslau R, Hawker CJ. Development of a Universal Alkoxyamine for “Living” Free Radical Polymerizations. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:3904–3920. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wadas TJ, Anderson CJ. Radiolabeling of TETA- and CB-TE2A-Conjugated Peptides with Copper-64. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:3062–3068. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]