Abstract

Background

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is associated with a high risk of stroke and may often be asymptomatic. AF is commonly undiagnosed until patients present with sequelae, such as heart failure and stroke. Stroke secondary to AF is highly preventable with the use of appropriate thromboprophylaxis. Therefore, early identification and appropriate evidence-based management of AF could lead to subsequent stroke prevention. This study aims to determine the feasibility and impact of a community pharmacy-based screening programme focused on identifying undiagnosed AF in people aged 65 years and older.

Methods and analysis

This cross-sectional study of community-based screening to identify undiagnosed AF will evaluate the feasibility of screening for AF using a pulse palpation and handheld single-lead electrocardiograph (ECG) device. 10 community pharmacies will be recruited and trained to implement the screening protocol, targeting a total of 1000 participants. The primary outcome is the proportion of people newly identified with AF at the completion of the screening programme. Secondary outcomes include level of agreement between the pharmacist's and the cardiologist's interpretation of the single-lead ECG; level of agreement between irregular rhythm identified with pulse palpation and with the single-lead ECG. Process outcomes related to sustainability of the screening programme beyond the trial setting, pharmacist knowledge of AF and rate of uptake of referral to full ECG evaluation and cardiology review will also be collected.

Ethics and dissemination

Primary ethics approval was received on 26 March 2012 from Sydney Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committee—Concord Repatriation General Hospital zone. Results will be disseminated via forums including, but not limited to, peer-reviewed publication and presentation at national and international conferences.

Clinical trials registration number

ACTRN12612000406808.

Article summary

Article focus

Describes the protocol for a community-based screening programme to identify previously undetected AF in adults aged 65 years and older in the community, for stroke prevention.

Key messages

Early identification of AF would allow for timely referral for medical review and subsequent initiation of appropriate evidence-based thromboprophylaxis to prevent stroke.

The efficacy of screening for AF in a community setting is yet to be tested in a well-designed clinical trial.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The main strengths of this study are that it uses a simple community-focused strategy using innovative technology to screen for AF, which may be suitable for widespread implementation. The technology delivers a single-lead electrocardiograph available for immediate interpretation and corroboration by an expert cardiologist remotely.

The sample size of 1000 will inform the design and refinement of a future large-scale intervention and implementation study.

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common heart arrhythmia, with a lifetime risk of 1:4 for adults worldwide,1 affecting at least 240 000 Australians.2 Prevalence rises with age from approximately 1% of the whole population to 5% in those older than 65 years.3 People with AF are up to seven times more likely to have a stroke than the general population and up to three times more likely to experience heart failure. AF-related strokes are also likely to be more severe.2 In addition, one in every six strokes is AF related,4 and more than 45 000 hospitalisations are caused by AF, with direct annual health system costs in Australia of $874 million.2

Many people in the general population are unaware that they have AF, with first diagnosis being made when they are admitted to hospital with a stroke or transient ischaemic attack.5 Our group undertook a review of 12-lead electrocardiograph (ECG) recordings taken in a preadmission clinic where ECGs are routinely performed on patients older than 40 years. Of the 2802 ECGs reviewed, AF was incidentally found in 12 patients (0.4%) and previously diagnosed in 100 patients (3.6%).6 Thromboprophylaxis based on CHADS2 scores was indicated in 10 of the 12 newly identified patients with AF, according to evidence-based guidelines.7 Additionally, 10 of the 12 newly identified patients with AF were asymptomatic. Another AF screening programme in the UK general practices identified previously unknown AF in 1.6% of screened patients, using pulse palpation and ECG.8

Furthermore, patients have poor knowledge of AF management and treatment, and the risks associated with AF.9 In a recent survey conducted by the American Heart Association, approximately 50% of those surveyed with AF did not know that they were at increased risk of stroke.10

Stroke is highly preventable in AF with the use of appropriate thromboprophylaxis.11 Therefore, early identification and appropriate evidence-based management of AF7 could lead to subsequent stroke prevention, significant reduction in the overall stroke burden and substantial savings to the health system.

AF screening in community pharmacies

Community pharmacies provide an ideal location, and an appropriate health professional/community interface, to screen people for AF. Approximately 90% of the Australian population visits a community pharmacy each year making it one of the most accessible healthcare services in the community.12 13 Additionally, patients older than 65 years with chronic conditions generally visit their community pharmacy at least monthly in order to fill prescriptions.14

Pharmacists are actively involved in the triage of medical problems presenting in the community, many of which are potentially serious.15 Community pharmacy also has a leading role in the management of many chronic medical problems, including cardiovascular disease management and general health screening.16–18 Recently, various professional practice incentives under the 5th Community Pharmacy Agreement have provided opportunities for community pharmacists to increase their role in chronic disease management.19 Involvement of community pharmacists in a screening project such as the one proposed here would enable performance of their obligations with regard to these incentives.

Methods and analysis

Design

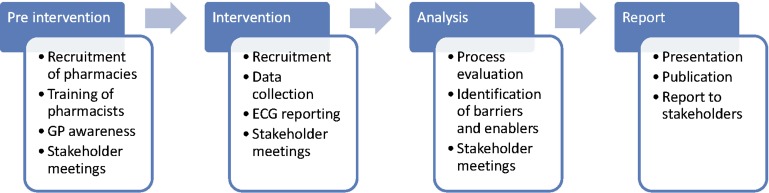

This study is a cross-sectional study of community-based screening to identify undiagnosed AF (figure 1) (ACTRN12612000406808). Screening will be offered in 10 community pharmacies in Sydney, Australia, and will be performed by the pharmacist on duty.

Figure 1.

SEARCH-AF study design.

Preintervention

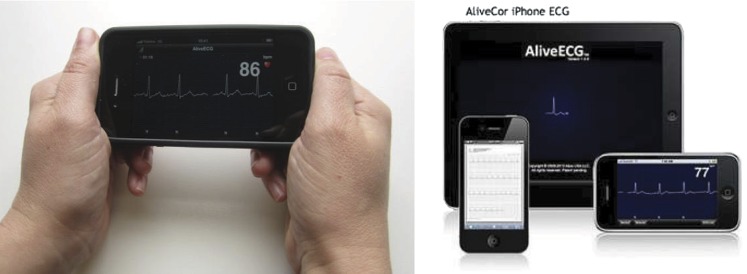

Local pharmacies will be invited to volunteer to participate in the study with a total of 10 pharmacies to be recruited. Community pharmacists working in these pharmacies will be educated regarding AF. Education will include the causes of AF, symptoms and evidence-based management, the health risks associated with AF, self-care management and cardiovascular risk reduction. The pharmacist will also be trained to obtain a relevant brief medical history related to cardiovascular disease, undertake pulse palpation, operate the AliveCor Heart Monitor for iPhone (handheld single-lead ECG)20 (figure 2) and interpret the single-lead ECG trace recording. Training of pharmacists will be undertaken using a structured training module, using a combination of online, centralised and onsite training, designed and delivered by a senior cardiologist, specialist nurse, specialist pharmacist and physiotherapist. Pharmacists will be required to demonstrate competency in essential skills and knowledge relating to AF diagnosis prior to initiating community pharmacy screening. Participating pharmacists will be eligible to claim Continuing Professional Development points on completion of the training module.

Figure 2.

AliveCor iPhone ECG.

Prior to commencement of the screening programme, participating pharmacists will provide information about the SEARCH-AF programme to the general practitioners in their local area. The information will outline the screening process, the pharmacist's involvement and the referral pathway for patients as outlined in the protocol.

A quality improvement framework is included to aid the refinement of the project through a continuous improvement design of evaluation, adjustment and re-evaluation. To aid this process, collaborative links with a stakeholder team will be developed, including representatives from consumer groups, general practitioners, the Medicare Local Network, pharmacists and the Pharmacy Guild.

Study population

All members of the general public attending pharmacies will be eligible to participate if they are aged 65 years or older, and if they provide informed consent. Those with a diagnosis of a severe coexisting medical condition that would prevent participation (eg, severe dementia or terminal illness) will be excluded from the study. This community sample is reasonably representative of the general population, as approximately 90% of the population visit pharmacies each year.12 13

Interventions

People eligible for screening will be asked by the community pharmacist if they are interested in participating in the study and provided with written information about the study. This will include explanation of the process of the screening including the sharing of information with their general practitioner and that ECGs collected during the screening process will be read by a cardiologist at Concord Hospital. Written and informed consent from all participants will be obtained by the pharmacist, prior to conducting the screening assessment.

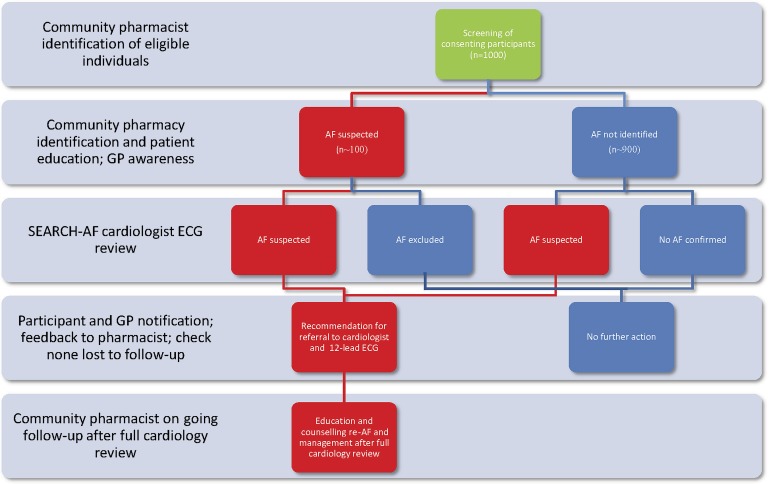

Availability of screening to the general public aged 65 years and older will be communicated via posters or flyers located within the pharmacy and at the entrance to the pharmacy. The pharmacist may also directly approach people in the pharmacy to invite them to undertake AF screening. There will be no charge for participation in the AF screening programme. Participants will also be welcome to tell their family and friends about the screening programme. The intervention flow chart is displayed in figure 3.

Figure 3.

Intervention flow chart.

Screening protocol

The screening will be approximately 5–10 min duration.

Screening will consist of an initial brief medical history, including pharmacotherapy and screen of AF symptoms. Pharmacists will perform a pulse palpation and record the result, then proceed to assess cardiac rhythm using the AliveCor iPhone handheld single-lead ECG device for 30–60 s.

The ECG record with a unique identification number will be transmitted by wireless connection on a secure server to an iCloud by the AliveCor software. The ECG record is only accessible by the cardiologist who will assess each ECG.

The pharmacist will advise the participant of the suspected diagnosis and ensure they understand it is not a definitive diagnosis and that the ECG will be reviewed by the cardiologist to either rule-out or rule-in the provisional diagnosis.

Every participant will be provided with written information on AF and how to check their pulse at home.

For every person screened, the pharmacist will send a letter to their general practitioner (GP) informing that their patient has been screened for AF, stating the suspected diagnosis, information regarding the research study, copies of the AF education handouts provided to the patient and outline how to contact the investigators if required. The letter will state that the research cardiologist will review the ECG and will contact the GP directly to advise if there are any abnormalities noted.

Protocol if a diagnosis of AF is suspected from the screening

The pharmacist will counsel the participant and advice that the SEARCH-AF team will contact them directly once the ECG is reviewed.

The pharmacist will inform the SEARCH-AF team of the suspected diagnosis within 24 h.

The ECG will be reviewed by the SEARCH-AF cardiologist within 24 h.

The participant will be contacted directly by the SEARCH-AF team to advise them of their result within 2–3 working days.

The SEARCH-AF team will call the GP to discuss the diagnosis and send a letter, which will include a copy of the ECG recording. If required, the letter will include an invitation to refer their patient for a full assessment at the Concord Hospital cardiology clinic or any other cardiology service of their choosing.

The pharmacist will call the participant approximately 1 month after the date of screening, to ensure they have not been lost to follow-up.

Protocol if AF is not suspected from the screening

All ECG's will be reviewed by the research cardiologist.

Those participants with an abnormal rhythm, not previously identified by the pharmacist, will be contacted directly by the SEARCH-AF team, counselled regarding the diagnosis and advised to return to their GP to discuss the next phase of their management. The SEARCH-AF team will call the GP to discuss the diagnosis and send a letter outlining the provisional diagnosis, including a copy of the ECG recording, and an invitation to refer their patient for a full assessment at the Concord Hospital cardiology clinic or any other cardiology service of their choosing.

Protocol if a history of AF is known prior to the screening

The pharmacist will send a letter to the participant's GP informing them that their patient was screened for AF, stating if they were in sinus rhythm or AF on the day of the screening.

All ECG's will be reviewed by the research cardiologist.

If an abnormality other than AF is identified, the following will occur: The participant will be contacted directly by the SEARCH-AF team, counselled regarding the diagnosis and advised to return to their GP to discuss the next phase of their management. The SEARCH-AF team will call the GP to discuss the diagnosis and send a letter outlining the provisional diagnosis, including a copy of the ECG recording, and an invitation to refer their patient for a full assessment at the Concord Hospital cardiology clinic or any other cardiology service of their choosing.

If the GP refers the participant to the Concord Hospital cardiology clinic, the full assessment will be performed by a Cardiologist, according to standard cardiology practice, and will include a 12-lead ECG. If appropriate, the patient may be commenced on appropriate thromboprophylaxis, according to evidence-based guidelines.7

Quality processes

The ability and accuracy of the pharmacist in interpretation of the ECG will be continually monitored. After reviewing each ECG, the research team will contact the pharmacist directly if an incorrect interpretation has been made. This will allow for feedback, mentoring and further training to improve the pharmacist's skill.

Study outcomes

Primary outcome

Proportion of screened subjects with newly identified AF in a community sample aged 65 years and older (determined from the cardiologists interpretation of the single-lead ECG)

Secondary outcomes

The level of agreement between the pharmacist's interpretations of the single-lead ECG compared with the cardiologist's interpretation of the single-lead ECG.

The level of agreement for identification of an irregular rhythm between pulse palpation by the pharmacist and the cardiologist's interpretation of the single-lead ECG taken from the AliveCore iPhone ECG monitor.

Proportion of participants that remain in AF, from the positive diagnosis from the single-lead ECG from the AliveCore iPhone ECG monitor to the 12-lead ECG performed during the cardiology review.

Process measures

A detailed process evaluation will be undertaken to better appreciate factors that might influence sustainability beyond the trial setting. After the final screening is complete, all participating pharmacists and a subsample of approximately 10 GP's involved in the care of the participants will be asked to complete a survey that will explore the barriers and enablers to the screening processes in the SEARCH-AF programme, and the effects it has had on the reported practice of the healthcare professionals involved with the participant. We will review the rate of uptake of referral to full ECG evaluation and cardiology review. In addition, we will evaluate the skills and knowledge of AF in all pharmacists involved with the screening intervention, prior to training and at the end of the screening programme.

Statistical considerations

Primary analyses will be conducted using SPSS for Windows (V.19.0). New episodes of AF will be expressed as true positives divided by total number screened with accompanying 95% CIs. A sample size of 1000 will provide a CI of ±0.8% assuming an incidence of 1.6%. χ2 tests will be used to compare new cases by gender and to identify associations between AF incidence and age group or AF risk factors. Two-tailed p values of <0.05 will be considered significant.

Ethics and dissemination

This study received formal ethical approval on 26 March 2012 from the Sydney Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committee—Concord Repatriation General Hospital zone. National Health and Medical Research Council ethical guidelines for human research will be adhered to, and written and informed consent will be obtained from all participants. The study will be administered by the Anzac Research Institute. Implementation and conduct of the study will be monitored by the project management committee (authors) who have extensive experience in qualitative research and conducting clinical trials in both cardiovascular disease and community pharmacies. The results of this study will be disseminated via the usual scientific forums, including peer-reviewed publication and presentations at international conferences.

Conclusions

AF is prevalent, affecting approximately 5% of those aged 65 years and older. Unrecognised AF is generally not associated with symptoms and raised resting heart rate. Those with unrecognised AF usually have stroke risk scores (ie, CHADS2 scores) high enough to warrant anticoagulation, which suggests that there are appreciable numbers of the well elderly in the community who would benefit from early recognition of AF through simple detection programmes, such as pulse palpation and recording an ECG, followed by thromboprophylaxis to prevent future stroke.

This cross-sectional study aims to determine the feasibility and impact of a community pharmacy-based screening, using innovative technology, focused on identifying people with undiagnosed AF, with onward referral to their GP for appropriate medical management of AF. The study also aims to explore the role of pharmacists in ongoing management of AF, as well their role in raising AF awareness in the general public. The study will inform the design and refinement of a future intervention for large-scale research and implementation.

The findings of this study will have broad implications for the general population aged 65 years and older with undiagnosed AF. We anticipate that this study will demonstrate that it is possible to identify and treat people in the community who were not previously known to have AF, thus greatly reducing the risk of stroke.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

To cite: Lowres N, Freedman SB, Redfern J, et al. Screening Education And Recognition in Community pHarmacies of Atrial Fibrillation to prevent stroke in an ambulant population aged ≥65 years (SEARCH-AF stroke prevention study): a cross-sectional study protocol. BMJ Open 2012;2:e001355. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001355

Contributors: SBF conceived the original concept of the study. All authors contributed to the design of the study, are involved in the implementation of the project and have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by an Investigator-Initiated Grant from Bristol-Myers Squibb/Pfizer and a small project award from Boehringer-Ingelheim. JR is funded by a Postdoctoral Fellowship co-funded by the NHMRC and National Heart Foundation (632933). LN is an NHMRC early career fellow (APP1036763).

Competing interests: Financial disclosures for SBF include Servier Australia (regarding Ivabradine—consultancy, honoraria, travel support); Bayer Australia (regarding Rivaroxaban—consultancy, honoraria) and Boehringer-Ingelheim (regarding Dabigatran—travel support, research grants). Financial disclosures for AM include Pharmaceutical Society of Australia (travel support) and Australian Antidoping Research Panel (Board Member).

Ethics approval: Ethics approval was provided by Sydney Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committee—Concord Repatriation General Hospital zone (reference number: HREC/11/CRGH/274).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Lloyd-Jones D, Wang T, Leip E, et al. Lifetime risk for development of atrial fibrillation: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2004;110:1042–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.PricewaterhouseCoopers Commissioned by the National Stroke Foundation, The Economic Costs of Atrial Fibrillation in Australia. 2010. http://www.strokefoundation.com.au/index2.php?option=com_docman&task=doc_view&gid=318&Itemid=39 (accessed 15 Jan 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Majeed A, Moser K, Carroll K. Trends in prevalence of atrial fibrillation in general practice in England and Wales, 1994-1998: analysis of data from the general practice research database. Heart 2001;86:284–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marini C, De Santis F, Sacco S, et al. Contribution of atrial fibrillation to incidence and outcome of ischaemic stroke: results from a population-based study. Stroke 2005;36:1115–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin HJ, Wolf PA, Benjamin EJ, et al. Newly diagnosed atrial fibrillation and acute stroke. The Framingham Study. Stroke 1995;26:1527–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deif B, Freedman SB. Prevalence of unrecognized atrial fibrillation and stroke risk in an otherwise healthy population over 40: a significant target for stroke prevention (abstract). Stroke 2012;43:A2930 [Google Scholar]

- 7.The Task Force for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J 2010;31:2369–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fitzmaurice DA, Hobbs FD, Jowett S, et al. Screening versus routine practice in detection of atrial fibrillation in patients aged 65 or over: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2007;335:383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aliot E, Breithardt G, Brugada J, et al. An international survey of physician and patient understanding, perception, and attitudes to atrial fibrillation and its contribution to cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality. Europace 2010;12:626–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Heart Association Half of those with Atrial Fibrillation Don't Know of Increased Stroke Risk, Survey Finds. http://newsroom.heart.org/pr/aha/half-of-those-with-atrial-fibrillation-215647.aspx (accessed 10 Nov 2011).

- 11.Chan PS, Maddox TM, Tang F, et al. Practice-level variation in warfarin use among outpatients with atrial fibrillation (from the NCDR PINNACLE program). Am J Cardiol 2011;108:1136–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benrimoj SI, Frommer MS. Community pharmacy in Australia. Aust Health Rev 2004;28:238–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joyce AW, Sunderland VB, Burrows S, et al. Community pharmacy's role in promoting healthy behaviours. J Pharm Pract Res 2007;37:42–4 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kansanaho H, Isonen-Sjölund N, Pietilä K, et al. Patient counselling profile in a Finnish pharmacy. Patient Educ Couns 2002;47:77–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chapman CB, Marriott JL, van den Bosch D. The Nature, Extent and Impact of Triage Provided by Community Pharmacy in Victoria. Pharmacy Guild of Australia, 2010. http://www.guild.org.au/iwov-resources/documents/The_Guild/PDFs/CPA%20and%20Programs/4CPA%20General/IIG-008/IIG008%20Full%20Final%20Report%20Triage%20Project.pdf (accessed 15 Feb 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krass I, Mitchell B, Song YJ, et al. Diabetes Medication Assistance Service Stage 1: impact and sustainability of glycaemic and lipids control in patients with Type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med 2011;28:987–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peterson GM, Fitzmaurice KD, Kruup H, et al. Cardiovascular risk screening program in Australian community pharmacies. Pharm World Sci 2010;32:373–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joyce A, Berbatis CG, Sunderland VB, et al. Analysis of primary prevention services for cardiovascular disease in Australia's community pharmacies. Aust N Z J Public Health 2007;31:516–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Government Department of Health and Ageing & the Pharmacy Guild of Australia 5th Community Pharmacy Agreement, Canberra, 2011. http://www.guild.org.au/iwov-resources/documents/The_Guild/PDFs/Other/Fifth%20Community%20Pharmacy%20Agreement.pdf (accessed 15 Feb 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saxon LA, Smith A, Doshi S, et al. iPhone rhythm strip: clinical the implications of wireless and ubiquitous heart rate monitoring. JACC 2012;59(13 Suppl):E726 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.