Abstract

We describe the case of a 35-year-old man with severe, dilated idiopathic cardiomyopathy who was placed on the waiting list for cardiac transplantation. While awaiting transplantation, his heart failure decompensated to such a degree that left ventricular assist device support was necessary. He did well on device support until a pump-pocket infection (methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative staphylococci) developed at 10 months. At that time, echocardiograms showed normal heart size and an ejection fraction of 0.45 to 0.49 without pump support. The pump was, therefore, explanted emergently. The patient has remained clinically stable with preserved ventricular function nearly 13 years after the explantation procedure.

Key words: Cardiomyopathy, dilated/complications/physiopathology; cardiovascular agents/therapeutic use; device removal; heart failure/therapy; heart-assist devices; treatment outcome; ventricular dysfunction, left/physiopathology

In patients with end-stage heart failure, mechanical circulatory support with a left ventricular assist device (LVAD) has led to improved native heart function. In some patients, prolonged LVAD support has resulted in enough improvement to permit LVAD explantation, thus allowing symptoms to be managed medically without a need for additional LVAD support or cardiac transplantation.1–5

Herein, we describe the case of a patient with idiopathic cardiomyopathy whose heart was unloaded by an LVAD for 10 months before the device had to be explanted emergently. This case shows that LVAD implantation in suitable candidates can lead to improved cardiac and end-organ function, enabling device removal.

Case Report

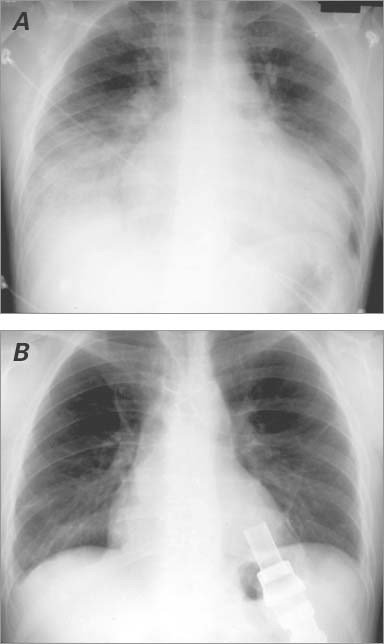

In February 1997, a 35-year-old man with a history of advanced heart failure secondary to idiopathic cardiomyopathy was evaluated at our hospital. He had a strong family history of heart failure (father, sister, and cousin). Because his condition continued to deteriorate, he was placed on the waiting list for cardiac transplantation. In September 1998, he returned with decompensated heart failure. A chest radiograph showed marked cardiomegaly and pulmonary edema secondary to heart failure (Fig. 1A). Right-sided heart catheterization showed decreases in cardiac output to 3.12 L/min and in cardiac index to 1.68 L/min/m2. Echocardiography showed a severely dilated left ventricle (LV) and severely depressed LV function (LV diastolic dimension, 7.5 cm; estimated ejection fraction [EF], <0.20). An intra-aortic balloon pump was inserted.

Fig. 1 Chest radiographs of the patient's heart show A) marked cardiac enlargement before left ventricular assist device implantation and B) normal ventricular size before explantation.

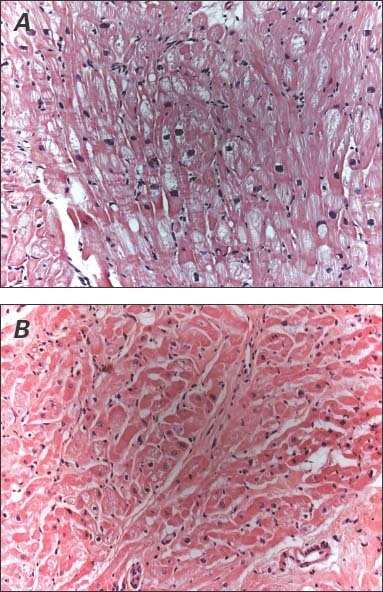

Because the cardiac decompensation was so severe, the patient qualified for LVAD implantation for continued circulatory support. Results of a heart biopsy verified myocyte degeneration and myocardial hypertrophy (Fig. 2A). The HeartMate® XVE LVAD (Thoratec Corporation; Pleasanton, Calif) was successfully implanted in November 1998. The patient's condition improved enough to enable his discharge from the hospital within a month. He was prescribed our routine medical regimen of warfarin (5–7.5 mg/d), metoprolol (5 mg twice daily), and digoxin (0.125 mg/d).

Fig. 2 Representative myocardial samples show A) myocyte degeneration and myocardial hypertrophy before left ventricular assist device implantation and B) myocyte hypertrophy and endomyocardial fibrosis after explantation (H & E, orig. ×20).

In early July 1999, the patient returned with a 3-week history of malaise and fever. He was diagnosed with a pump-pocket infection, and cultures revealed methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative staphylococci that could not be treated with intravenous antibiotics. Follow-up cardiac catheterization to determine his candidacy for LVAD explantation showed a pulmonary artery pressure of 16/5/11 mmHg, a pulmonary capillary wedge pressure of 4/4/3 mmHg, and cardiac output of 6.42 L/min. Dobutamine stress echocardiography showed that ventricular size was within normal ranges. The LVEF was 0.45 to 0.49. Results of a chest radiograph were normal (Fig. 1B). Therefore, it was decided to explant the LVAD. A concomitant biopsy of the LV again verified the presence of endomyocardial fibrosis and myocyte hypertrophy (Fig. 2B). However, this biopsy was taken from an area adjacent to the sewing cuff. The patient tolerated the explantation procedure well. He was discharged from the hospital 2 months later on a medical regimen of amiodarone (200 mg twice daily), metoprolol (5 mg twice daily), furosemide (40 mg every other day), and digoxin (0.125 mg every other day).

One year after LVAD removal, the patient had an episode of ventricular tachycardia for which an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (Medtronic, Inc.; Minneapolis, Minn) was inserted. Subsequent yearly echocardiographic follow-up showed no change in LVEF or in ventricular or atrial size. In 2005, he relocated to another city and continued to do well. As of February 2012, his current LVEF was approximately 0.40. He reported that he was active and could climb stairs without difficulty.

Discussion

This report describes the case of a patient with advanced, chronic heart failure who was awaiting heart transplantation but required LVAD implantation as a life-saving intervention when his condition deteriorated. While he was supported by the LVAD, he walked at least 2 miles daily, 5 times weekly. When he was diagnosed with a resistant pump-pocket infection, a heart was still not available, and the LVAD had to be explanted emergently. During the period in which he was supported by the LVAD, his cardiac function had improved to New York Heart Association functional class I, and it remained so after the device was removed. Because of the patient's improved clinical status, he elected not to undergo transplantation. His condition remained stable nearly 13 years after LVAD removal.

In this case, the LVAD was implanted as a bridge to transplantation and was explanted only because of the life-threatening infection, which also prevented us from weaning our patient from the device. Usually, the best results can be achieved when the unloaded ventricle is reconditioned through weaning before explantation. However, this patient's exercise regimen may have inadvertently helped to recondition the ventricle. Although histologic results showed an improved architecture, the histology was not normal, and the patient's latest echocardiograms continued to show decreased cardiac function. However, as of the last examination, his condition was being managed medically, and the heart-failure symptoms had not returned.

This patient's case shows the potential for cardiac function to improve enough—even in patients with advanced, chronic heart failure—to enable LVAD removal. Burch and colleagues6 were the first to quantify the importance of resting the myocardium to treat heart failure. Reports since then have documented improved cardiac function after resting the myocardium with an LVAD.7,8 However, until recently, there were no prospective trials designed to implement the LVAD as a therapeutic agent.5,9 This case shows that not only can improvement in myocardial function permit even emergent removal of the device but that the improvement can be sustained.

The precise cause of most dilated cardiomyopathies remains obscure. Therefore, we believe it best to consider such patients as having progressed from decompensated to compensated heart failure and also to consider them in remission from heart failure, rather than recovered from it. If patients with these conditions can improve enough to be treated successfully with medications for prolonged periods without device support or cardiac transplantation, important clinical and economic benefits can be achieved, particularly in younger patients with heart failure.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge Marianne Mallia, ELS, for her editorial assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Address for reprints: O.H. Frazier, MD, Texas Heart Institute, P.O. Box 20345, MC 2-114A, Houston, TX 77225-0345

E-mail: lschwenke@texasheart.org

References

- 1.Dandel M, Weng Y, Siniawski H, Stepanenko A, Krabatsch T, Potapov E, et al. Heart failure reversal by ventricular unloading in patients with chronic cardiomyopathy: criteria for weaning from ventricular assist devices. Eur Heart J 2011;32 (9):1148–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Dandel M, Weng Y, Siniawski H, Potapov E, Lehmkuhl HB, Hetzer R. Long-term results in patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy after weaning from left ventricular assist devices. Circulation 2005;112(9 Suppl):I37–45. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Birks EJ, Tansley PD, Hardy J, George RS, Bowles CT, Burke M, et al. Left ventricular assist device and drug therapy for the reversal of heart failure. N Engl J Med 2006;355(18):1873–84. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Hetzer R, Muller JH, Weng YG, Loebe M, Wallukat G. Midterm follow-up of patients who underwent removal of a left ventricular assist device after cardiac recovery from end-stage dilated cardiomyopathy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2000;120 (5):843–53. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Slaughter MS, Rogers JG, Milano CA, Russell SD, Conte JV, Feldman D, et al. Advanced heart failure treated with continuous-flow left ventricular assist device. N Engl J Med 2009; 361(23):2241–51. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Burch GE, Walsh JJ, Ferrans VJ, Hibbs R. Prolonged bed rest in the treatment of the dilated heart. Circulation 1965;32(5): 852–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Frazier OH, Benedict CR, Radovancevic B, Bick RJ, Capek P, Springer WE, et al. Improved left ventricular function after chronic left ventricular unloading. Ann Thorac Surg 1996;62 (3):675–82. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Khan T, Delgado RM, Radovancevic B, Torre-Amione G, Abrams J, Miller K, et al. Dobutamine stress echocardiography predicts myocardial improvement in patients supported by left ventricular assist devices (LVADs): hemodynamic and histologic evidence of improvement before LVAD explantation. J Heart Lung Transplant 2003;22(2):137–46. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Rose EA, Gelijns AC, Moskowitz AJ, Heitjan DF, Stevenson LW, Dembitsky W, et al. Long-term use of a left ventricular assist device for end-stage heart failure. N Engl J Med 2001; 345(20):1435–43. [DOI] [PubMed]