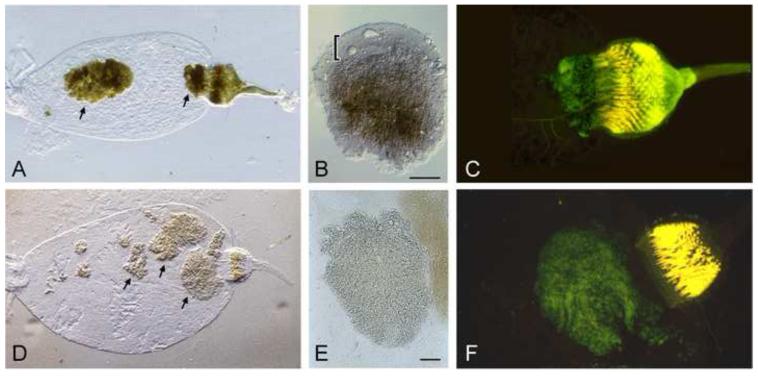

Figure 2.

The Y. pestis life stage in the flea. (A) Digestive tract from an X. cheopis flea dissected two weeks after infection with wild-type Y. pestis. Arrows indicate large aggregates of bacteria, one of which fills the proventriculus. (B) Wild-type Y. pestis aggregate dissected from the midgut. The dense mass of bacteria is brown-pigmented due to hmsHFRS-dependent sequestration of hemin derived from the flea blood meal and is enveloped by a viscous layer (indicated by the bracket) composed of biofilm ECM and lipid components, also derived from the blood meal [16]. (C) Fluorescence micrograph of the digestive tract from a flea blocked with wild-type Y. pestis expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP). The PV is swollen due to the large bacterial mass that fills it. (D) Digestive tract from a flea dissected two weeks after infection with hmsHFRS− Y. pestis. Multicellular aggregates of bacteria are present in the midgut but the proventriculus is uninfected. (E) Aggregate of hmsHFRS− Y. pestis dissected from the midgut. The bacterial aggregate is not pigmented and not surrounded by ECM. (F) Fluorescence micrograph of the digestive tract from a flea infected with hmsHFRS− Y. pestis expressing GFP. The infection is confined to the midgut and does not involve the proventriculus. Dissected digestive tracts in both Fig. 1 and Fig. 2 were mounted in H20, which clears red blood cell material from previous blood meals but not the bacterial aggregates. MG, midgut; PV, proventriculus; E, esophagus; ECM, extracellular matrix. Scale bars = 0.05 mm.