Abstract

Qualitative screening of 295 fungi for laccases yielded 125 laccase positive ones, mostly basidiomycetes. Fifty of these were tested for laccase activity at pH 3.0, 4.5 and 6.0. Most showed maximum activity at pH 4.5, a few showed a broad activity range, two were optimal at pH 3.0 and only the mitosporic fungus Beltraniella sp. was best at pH 6. Most of the 25 fungi assayed at three different temperatures had an optimum at 45°C. The basidiomycete Auricularia sp. acted best at 30°C, while three others showed best activity at 60°C. This study shows the potential of screening diverse fungi for laccase with varying pH and temperature preferences for different applications.

Keywords: Fungi, Laccase, pH, Temperature, Optima

Laccases are multicopper enzymes found in bacteria, fungi and plants. They catalyze the oxidation of phenols and polyphenols, besides many nonphenolic compounds, resulting in reduction of molecular oxygen to water [1]. Fungal laccases occur in Ascomycota, Basidiomycota and mitosporic fungi [2]. Basidiomycetous white rot fungi such as Trametes versicolor, Pleurotus ostreatus and Ganoderma lucidum are excellent laccase producers [3]. Laccases are used in paper, textile, bioremediation and other industries [1, 2]. Such applications would benefit by laccases with different pH and temperature optima. We screened a large number of fungi for laccases for these properties. Cultures from in-house collection of the organization were used. These were identified based on morphology, using standard monographs. Initial qualitative screening was by inoculating a 5 mm. diam mycelial disc of 5 day old culture onto PDA plates containing 4 mM guaiacol. Intense brown coloration around the fungal colony was considered positive for laccase production [4].

A 5 mm mycelial disc of 7 day old culture was inoculated into 150 ml Erlenmeyer flask containing 30 ml Malt Extract broth (MEB) and grown stationarily. After 7 days, sterile glass beads were added and the mycelium was homogenized by shaking. A 5% inoculum (v/v) was transferred to 20 ml of MEB in a 100 ml Erlenmeyer flask. Three replicates were incubated for 20 days at 25°C in stationary condition. Copper sulphate (2 mM end concentration) was added in some experiments after 7 days. Enzyme was harvested by filtration using 0.45 μm Millipore filter. Spectrophotometric assays were carried out at 405 nm using 1 mM 2,2′-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulphonic acid) (ABTS) [5] at pH, 3.0, 4.5 and 6.0, using appropriate buffers and further at 30, 45 and 60°C temperatures. One laccase unit is defined as μmoles of product formed per minute per ml of culture supernatant.

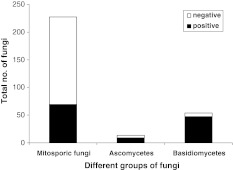

Of the total 295 fungi screened qualitatively, 125 were positive (Fig. 1). Forty-seven of fifty-four basidiomycetes (87%) and 9 of 14 ascomycetes (64%), but only 69 of 227 mitosporic and non-sporulating fungi (30%) indicated laccase activity. White-rot basidiomycetes commonly produce laccase [3]. Guaiacol plate assay helps in identifying laccase-positive fungi, but is not specific, several other oxidases also producing a colour on guaiacol plates [6]. Therefore, fifty cultures producing the broadest bands of guaiacol oxidation were selected for further quantitative estimation.

Fig. 1.

Qualitative screening of fungi for laccase of cultures

Fungi differ in their optimal media for laccase. MEB, which is a useful medium for laccase production [7] was chosen as the medium for comparative purposes. Among the 50 cultures comprising 34 basidiomycetes, 1 ascomycete, 13 mitosporic and 2 unidentified fungi assayed, several isolates of Lentinus, as well as an isolate of Ganoderma and Fomitopsis produced >1500 Units l−1 laccase even under unoptimized MEB media conditions, emphasizing the importance of basidiomycetes in laccase production (Table 1). The first two genera are known to produce high amounts of laccase [8, 9]. Copper sulphate induced laccase in three of four fungi (Table 1). Although basidiomycetes are generally the candidates for laccase, a few mitosporic fungi are also good laccase producers [1]. Interestingly, the mitosporic fungus, Geotrichum sp., isolated from mushrooms produced high amounts of 1723 Units l−1 of laccase. Geotrichum is known to transform several azo- and anthraquinone dyes, presumably owing to laccase [10]. Although a few ascomycetes produce laccase, we found only a single ascomycete with moderate amounts of laccase (319 Units l−1; Table 2).

Table 1.

Laccase activity at different pH

| No. | Fungus | Substrate | Laccase Units l−1 at three different pH | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3.0 | 4.5 | 6/8* | |||

| 1 | Agaricus heterocystis | Soil | 72.34 | 122.4 | 20.6 |

| 2 | Agaricus sp. | Soil | 10.29 | 17.49 | 0* |

| 3 | Agaricus sp. | Soil | 13.99 | 173.02 | 13.7 |

| 4 | Anthracophyllum nigritum | Wood | 6.34 | ND | ND |

| 5 | Auricularia sp. | Wood | 4.46 | 113.14 | 115.2 |

| 4.9 | 143.31 | 90.5 | |||

| 6 | Chlorophyllummolybdites | Soil | 113.83 | 752.57 | 0* |

| 7 | Clarkienda sp. | Soil | 25.44 | 179.31 | 80.2 |

| 8 | Coprinus sp. | Soil | 12.82 | 879.43 | 1.13* |

| 9 | Fomitopsis sp. | Wood | 1464 | 1194 | 249 |

| 10 | Ganoderma sp. | Wood | 1848 | 1933 | 751 |

| 11 | Hygrocybe sp. | Soil | 63.09 | 62.57 | 12.1 |

| 12 | Lentinus bambussimus | Soil | 428.57 | 1498.3 | 325 |

| 13 | Lentinus sp. | Soil | 764.57 | 1968 | 2.06* |

| 574.8 | 989.14 | 269.66 | |||

| 14 | Lentinus sp. | Wood | 11.38 | ND | ND |

| 15 | Lentinus sp. | Wood | 90.77 | 438.86 | 144.7 |

| 90.17 | 574.63 | 82.63 | |||

| 16 | Lentinus sp. | Wood | 318 | 1777.7 | 672 |

| 17 | Leucocoprinus sp. | Wood | ND | ND | 56.81 |

| 36 | 94.87 | 37.37 | |||

| 18 | Leucocoprinus sp. | Wood | 18.86 | 80.06 | 18.7 |

| 19 | Macrolepiota sp. | Soil | 81.26 | 380.57 | 131.8 |

| 54.34 | ND | ND | |||

| 20 | Marasmiellus sp. | Wood | 0 | 15.09 | 3.43* |

| 21 | Marasmius sp. | Wood | 0 | ND | ND |

| 22 | Marasmius sp. | Wood | 3.09 | 33.6 | 17.1 |

| 23 | Microporus sp. | Wood | 0.34 | 0 | 0 |

| 24 | Mycena sp. | Soil | 24 | 18.86 | 0* |

| 25 | Mycena sp. | Wood | 11.93 | ND | ND |

| 26 | Pleurotus sp. | Wood | 121.37 | 134.74 | 136.11 |

| 27 | Pleurotus sp. | Wood | 60 | 202.29 | 97.4 |

| 28 | Polypore | Wood | 4.17 | 0 | 5.04 |

| 29 | Polypore | Wood | 0 | 0 | 0* |

| 30 | Polypore | Wood | 37.71 | 40.8 | 34.3 |

| 31 | Russula sp. | Soil | 8.38 | 9.09 | 9.6 |

| 32 | Unidentified basidiomycete | Soil | 6.5 | ND | ND |

| 33 | Unidentified basidiomycete | Wood | 0 | 0 | 0* |

| 34 | Unidentified basidiomycete | Soil | 28.8 | 96 | 44.4 |

| 33.94 | 157 | 56.9 | |||

| 35 | Beltraniella sp. | Endophyte | 26.79 | 28.11 | 51.4 |

| 36 | Bisporomyces sp. | Litter | 0.82 | 2.5 | 0 |

| 37 | Dictyochaeta sp. | Litter | 2.54 | 0.39 | 0 |

| 38 | Dictyocheata sp. | Litter | 5.31 | 6.34 | 4.29 |

| 39 | Excipularia sp. | Litter | 9.27 | 0 | 0 |

| 40 | Geotrichum sp. | Mushroom | 1040.6 | 1722.9 | 1126 |

| 41 | Gyrothrix sp. | Litter | 1.18 | 9.43 | 3.31 |

| 42 | Monodictys sp. | Litter | 11.67 | 61.87 | 1.87 |

| 43 | Robillarda sp. | Endophyte | 0 | 0 | 0* |

| 44 | Selenodriella sp. | Litter | 4.71 | 14.86 | 4.3 |

| 45 | Unidentified fungus | Litter | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 46 | Unidentified fungus | Litter | 0.75 | 0.27 | 0 |

| 47 | Unidentified mitosporic fungus | Litter | 30.39 | 27.77 | 17.5 |

| 48 | Unidentified mitosporic fungus | Litter | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 49 | Unidentified mitosporic fungus | Litter | 137.83 | 192.34 | 164 |

| 50 | Unidentified ascomycete | Litter | 99.26 | 77.34 | 107 |

Highest activity for each fungus and values that fell within 75% of that are shown in bold and considered optimal pH for that fungus

Italicized rows cultures grown in MEB medium; 2 mM CuSO4 added to culture on 7th day

Non Italicized rows cultures grown in MEB medium in absence of CuSO4

ND not determined

*Fungi assayed at pH 8.0

Table 2.

Laccase activity at different temperatures

| No. | Isolates | 30°C (U/l) | 45°C (U/l) | 60°C (U/l) | Substrate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Agaricus sp. | 393 | 385 | 5 | Soil |

| 2 | Agaricus heterocystis | 1611 | 2400 | 2194 | Soil |

| 3 | Auricularia sp. | 80.57 | 22 | 37.7 | Wood |

| 4 | Chlorophyllum molybdites | 85.71 | 624 | 178 | Wood |

| 5 | Clarkienda sp. | 160 | 277 | 341 | Soil |

| 6 | Excipularia sp. | 9.89 | 15.89 | 27 | Litter |

| 7 | Ganoderma sp | 494 | 778 | 668 | Wood |

| 8 | Geotrichum sp. | 3925 | 4892 | 2965 | Mushroom |

| 19 | Hygrocybe sp. | 98 | 226 | 217 | Soil |

| 10 | Lentinus bambussimus | 3918 | 5434 | 2909 | Soil |

| 11 | Lentinus sp. | 1275 | 1474 | 1251 | Wood |

| 12 | Lentinus sp. | 306 | 579 | 126 | Wood |

| 13 | Lentinus sp. | 685.7 | 377 | 771 | Soil |

| 14 | Lentinus sp. | 150 | 996 | 1119 | Wood |

| 15 | Macrolepiota sp. | 341 | 720 | 866 | Soil |

| 16 | Monodictys sp. | 52.46 | 65.31 | 80.9 | Litter |

| 17 | Pleurotus sp. | 113 | 156 | 93 | Wood |

| 18 | Pleurotus sp. | 0.12 | 0.29 | 0.49 | Wood |

| 19 | Schizophyllum sp. | 3.21 | 4.29 | 5.26 | Wood |

| 20 | Selenodriella sp. | 38.22 | 39.25 | 17.6 | Litter |

| 21 | Termitomyces sp. | 428 | 514 | 798.8 | Wood |

| 22 | Polypore | 3497 | 4261.7 | 4479 | Wood |

| 23 | Unidentified ascomycete | 123.9 | 318.86 | 43.37 | Litter |

| 24 | Unidentified | 12 | 21.6 | 10 | Litter |

| 25 | Unidentified | 18.69 | 28.6 | 15.43 | Litter |

Highest activity for each fungus and values that fell within 75% of that are shown in bold and considered optimal temperature for that fungus

Twenty four of 50 fungi showed best laccase activity at pH 4.5 (Table 1). Of these, 19 were basidiomycetes and 5 were mitosporic fungi. Laccases of white-rot fungi are mostly optimal at pH 3.0 to 5.5 [11, 12]. Two mitosporic fungi Dictyochaeta sp., Excipularia sp. and an unidentified fungus showed an optimal pH solely at 3.0, as has also been reported in a marine isolate of the basidiomycete Cerrena versicolor, Ganoderma lucidum and Phanerochaete flavido-alba [9, 13, 14]. Only the mitosporic species, Beltraniella sp. preferred pH 6.0. Four basidiomycetes, Mycena sp., Hygrocybe sp., Ganoderma sp. and Fomitopsis sp., besides an unidentified mitosporic fungus preferred pH 3.0 and 4.5. Three basidiomycetes, Pleurotus sp., Russula sp., and a polypore, an unidentified ascomycete, and the mitosporic fungus Dictyochaeta sp. showed a broad pH range for laccase activity at all three pH. None of the nine fungi tested at pH 8.0 instead of 6.0 showed good activity at this pH (Table 1).

Twenty fungi from the 50 in Table 1, and also 5 others were selected based on high laccase activity and different pH preferences for further assays on temperature optima at 30, 45 and 60°C (Table 2). Six showed optimum activity at 45°C. Only the basidiomycete Auricularia sp. showed best activity at 30°C. Enzymes with room temperature optima are advantageous. A temperature optimum of 20°C has been reported for Ganoderma lucidum [9]. A preference for 60°C was rare, only Pleurotus sp., Termitomyces sp. and Excipularia sp. showing this (Table 2). D’Souza et al. [13]. found such a high temperature optimum in a marine isolate of Cerrena unicolor. Lentinus bambussimus and a polypore showed high laccase activity at all three temperatures.

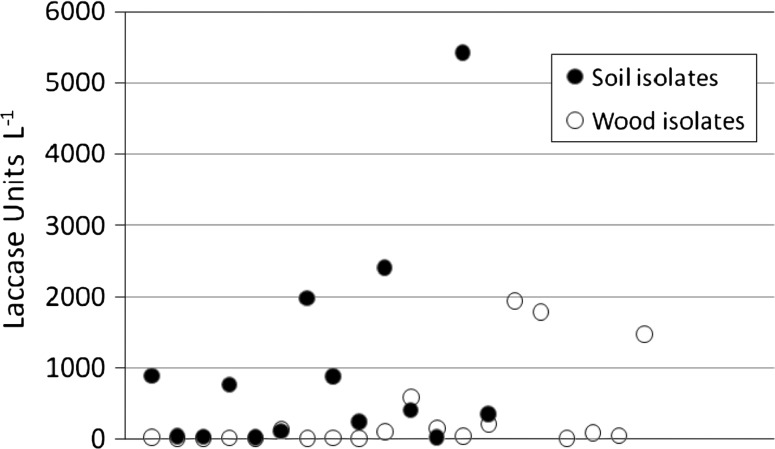

Wood-degrading basidiomycetes are generally the best laccase sources. This study suggests that fungi from other sources are equally useful, often yielding higher amounts of laccase than the former (Fig. 2; Tables 1, 2). Thus, the best laccase producers were two non-wood isolates, Lentinus bambussimus and Geotrichum sp., which produced 5434 and 4892 Units l−1 respectively (Table 2).

Fig. 2.

Laccase activity of fungi isolated from soil and wood

This study shows the usefulness of screening diverse fungi to obtain laccases of varying pH and temperature optima. It yielded a high laccase-producing mitosporic fungus, Geotrichum sp., with a pH optimum of 4.5 and temperature optimum of 30 and 45°C (Table 2). Fungi with laccases of different pH and temperature optima could be the basis of further studies, leading to specific applications.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Department of Biotechnology, Ministry of Science and Technology, Government of India, under its Small Business Innovation Research Initiative (SBIRI) Programme.

References

- 1.Baldrian P. Fungal laccases-occurrence and properties. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2006;30:215–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-4976.2005.00010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kunamneni A, Camarero S, Garcia-Burgos C, Plou F, Ballesteros A, Alcalde M. Engineering and applications of fungal laccases for organic synthesis. Microb Cell Fact. 2008;7:32. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-7-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eriksson, K E L, Blanchette RA, Ander P (1990). Biodegradation of lignin. In: Timell T (ed) Microbial and enzymatic degradation of wood and wood components. Springer, Berlin, pp 225–334

- 4.D’Souza D, Tiwari R, Kumar Sah A, Raghukumar C. Enhanced production of laccase by a marine fungus during treatment of colored effluents and synthetic dyes. Enzym Microb Technol. 2006;38:504–511. doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2005.07.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Niku-Paavola ML, Karhunen E, Salola P, Raunio V. Ligninolytic enzymes of the white-rot fungus Phlebia radiata. Biochem J. 1988;254:877–884. doi: 10.1042/bj2540877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kiiskinen L, Ratto M, Kruus K. Screening for novel laccase-producing microbes. J Appl Microbiol. 2004;97:640–646. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2004.02348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arora DS, Rampal P. Laccase production by some Phlebia species. J Basic Microbiol. 2002;42:295–301. doi: 10.1002/1521-4028(200210)42:5<295::AID-JOBM295>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shutova V, Revin V, Myakushina Yu. The effect of copper ions on the production of laccase by the fungus Lentinus (Panus) tigrinus. Appl Biochem Microbiol. 2008;44(6):619–623. doi: 10.1134/S0003683808060100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ko EM, Leem YE, Choi HT. Purification and characterization of laccase isozymes from the white-rot basidiomycete Ganoderma lucidum. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2001;57(1–2):98–102. doi: 10.1007/s002530100727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maximo C, Pessoa Amorim M, Costa-Ferreira M. Biotransformation of industrial reactive azo dyes by Geotrichum sp. CCMI 1019. Enzym Microb Technol. 2003;32(1):145–151. doi: 10.1016/S0141-0229(02)00281-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bollag J, Leonowicz A. Comparative studies of extracellular fungal laccases. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1984;48(4):849–854. doi: 10.1128/aem.48.4.849-854.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coll P, Fernandez-Abalos J, Villanueva J, Santamaria R, Perez P. Purification and characterization of a phenoloxidase (laccase) from the lignin-degrading basidiomycete PM1 (CECT 2971) Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59(8):2607–2613. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.8.2607-2613.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.D’Souza-Ticlo D, Sharma D, Raghukumar C. A thermostable metal-tolerant laccase with bioremediation potential from a marine-derived fungus. Mar Biotechnol. 2009;11(6):725–737. doi: 10.1007/s10126-009-9187-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perez J, Martinez J, Rubia T. Purification and partial characterization of a laccase from the white rot fungus Phanerochaete flavido-alba. Appl Environ Microb. 1996;62(11):4263–4267. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.11.4263-4267.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]