Abstract

Objective

Otolaryngic disorders are very common in primary care, comprising 20–50% of presenting complaints to a primary care provider. There is limited otolaryngology training in undergraduate and postgraduate medical education for primary care. Continuing medical education may be the next opportunity to train our primary care providers (PCPs). The objective of this study was to assess the otolaryngology knowledge of a group of PCPs attending an otolaryngology update course.

Methods

PCPs enrolled in an otolaryngology update course completed a web-based anonymous survey on demographics and a pre-course knowledge test. This test was composed of 12 multiple choice questions with five options each. At the end of the course, they were asked to evaluate the usefulness of the course for their clinical practice.

Results

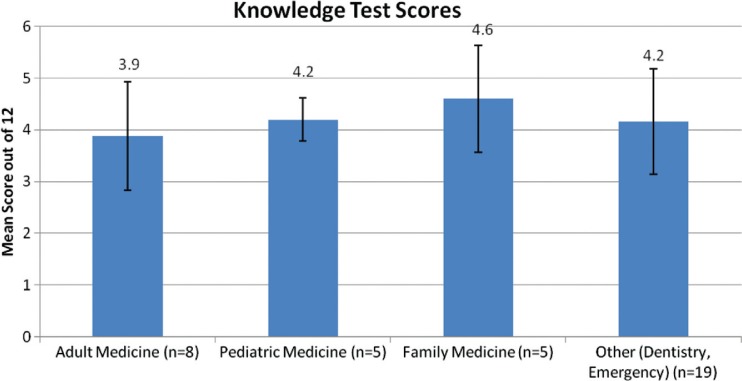

Thirty seven (74%) PCPs completed the survey. Mean knowledge test score out of a maximum score of 12 was 4.0±1.7 (33.3±14.0%). Sorted by area of specialty, the mean scores out of a maximum score of 12 were: family medicine 4.6±2.1 (38.3±17.3%), pediatric medicine 4.2±0.8 (35.0±7.0%), other (e.g., dentistry, emergency medicine) 4.2±2.0 (34.6±17.0%), and adult medicine 3.9±2.1 (32.3±17.5%). Ninety one percent of respondents would attend the course again.

Conclusion

There is a low level of otolaryngology knowledge among PCPs attending an otolaryngology update course. There is a need for otolaryngology education among PCPs.

Keywords: primary care providers, continuing medical education

Otolaryngic issues comprise a significant portion of presenting complaints to primary care. Approximately 20% of adult general practice consultations are for otolaryngology complaints (1)1 . A survey on the prevalence of otolaryngic problems in the community reported that roughly one fifth of respondents complained of hearing loss, tinnitus, or vertigo. About 13–18% reported persistent nasal symptoms or hay fever. About 30% reported severe sore throat or tonsillitis. In the pediatric population, this number rises to around 50% (2, 3). It is imperative for primary care providers (PCPs) to know how to successfully diagnose and manage these otolaryngology disorders and to know when to appropriately refer to an otolaryngologist. These PCPs may be trained in family medicine, pediatrics, or emergency medicine, or be trained as allied health professionals, such as physician assistants (PAs), nurse practitioners (NPs), and dentists.

A recent survey of over 1,000 primary care residents shows that they are not aware of the scope of practice of otolaryngology (4). Only 47.2% of primary care residents chose otolaryngologists as experts for thyroid surgery, 32.4% for sleep apnea, and 2.7% for restoring a youthful face. In fact, only 43% of patients are even aware that an otolaryngologist is a physician (5). There is obviously a misperception among PCPs regarding the role of an otolaryngologist. By analyzing these misperceptions, we may find areas for improvement in the training of PCPs in otolaryngology.

There are three opportunities to train a primary care provider in otolaryngology. The first is in medical school with undergraduate medical education. The second is in residency with postgraduate medical education (family medicine or pediatrics). The third is in practice with continuing medical education (CME). Several studies have examined the otolaryngology training in undergraduate medical education (6–11) and postgraduate medical education (12, 13). There is, however, a paucity of studies on CME in otolaryngology for PCPs. As specialists in otolaryngology, we bear part of the responsibility of educating our PCPs with whom we share patients. The purpose of this study was to assess the otolaryngology knowledge of a group of PCPs attending an otolaryngology update course.

Methods

A web-based anonymous survey was conducted among PCPs enrolled in an otolaryngology update course at our university institution. No remuneration was offered for completing this survey. This survey involved questions on demographic data and a pre-course knowledge test. The knowledge test was composed of 12 multiple choice questions with five options each. The knowledge test was created by two board certified otolaryngologists practicing at an academic institution, one of whom organized the otolaryngology update course. Examples of the questions are shown in Table 1. At the end of the course, the participants were asked to evaluate the usefulness of the course for their primary care practice.

Table 1.

Sample questions and answers from the pre-course knowledge test. There were a total of 37 participants, however, each participant could choose more than one answer per question, hence, the total number of responses was more than 37

| Sample questions | Response n (% total) |

|---|---|

| 1. What are the indications for tonsillectomy? | |

| (a) Six episodes of pharyngitis in 1 year | 13 (25%) |

| (b) Two documented suppurative tonsillitis in 1 year | 9 (18%) |

| (c) Very enlarged tonsils on exam | 2 (4%) |

| (d) Very loud snoring by parent report and tonsillary hypertrophy on exam | 10 (20%) |

| (e) All of the above | 17 (33%) |

| Correct answer is d | |

| Total | 51 (100%) |

| 2. When should ear tubes be placed? | |

| (a) Four episodes of documented recurrent otitis media over 12 months requiring antibiotics | 5 (12%) |

| (b) An ear effusion that lasts more than two months with documented hearing loss | 5 (10%) |

| (c) Bilateral sensorineural hearing loss for greater than four months | 1 (2%) |

| (d) Choices A and B | 31 (75%) |

| (e) None of the above | 0 (0%) |

| Correct answer is e | |

| Total | 41 (100%) |

| 3. You see an adult patient for complaints of hearing loss. On ear exam, there is a unilateral effusion of the right ear. What is the most appropriate next step? | |

| (a) Treat with antibiotics and re-examine | 15 (39%) |

| (b) Refer for a nasopharyngeal exam | 11 (29%) |

| (c) Order a CT scan of the head and neck | 3 (8%) |

| (d) All of the Above | 8 (21%) |

| (e) None of the Above | 1 (3%) |

| Correct answer is b | |

| Total | 38 (100%) |

Following acquisition of participant data, statistical analysis was performed using commercially available software packages (Catalyst and Microsoft Excel, 2007). Primary analyses included the percentage of correct responses to the knowledge test questions and calculation of means and standard deviations. Data was displayed with frequency charts. This study was reviewed by our institutional review board and deemed exempt.

Results

Thirty seven out of a total of 50 participants responded to the survey; thus, the response rate was 74%. The different specialty areas of the participants and their knowledge test scores are shown in Fig. 1. In descending order, the mean scores out of a maximum score of 12 were: family medicine 4.6±2.1 (38.3±17.3%) (n=5), pediatric medicine 4.2±0.8 (35.0±7.0%) (n=5), other (e.g., dentistry, emergency medicine) 4.2±2.0 (34.6±17.0%) (n=19), and adult medicine 3.9±2.1 (32.3±17.5%) (n=8). Overall, the mean knowledge score out of a maximum score of 12 was 4.0±1.7 (33.3±14.0%) (n=37). Among the 37 respondents, 16 (43.2%) were trained as medical doctors (MD) and 21 (56.8%) were trained as allied health professionals (e.g., NPs, PAs, dentists, etc.). The mean scores of the medical doctors were 4.7±1.6 (39.1±13.5%) and the mean scores of the allied health professionals were 3.8±2.0 (31.3±16.6%). This difference was not statistically significant (p=0.14). Table 1 shows the responses on three sample questions from the knowledge test. There were a total of 37 participants, however, each participant could choose more than one option per question, hence the total number of responses were more than 37.

Fig. 1.

Knowledge test scores sorted by area of specialty. The bars show the standard deviation.

At the end of the otolaryngology update course, the PCPs were asked to evaluate the course. Eleven out of the 50 (22%) responded to the post-course questionnaire. Ninety one percent of these respondents would attend the course again. When asked how often the course should be offered, 55% replied yearly, 36% replied every 2 years, and 18% replied every 3–5 years. The cost to attend this course was $125 for physicians and $100 for non-physicians. Sixty-four percent felt that the cost of attending the course was fair.

Discussion

The importance of otolaryngology in primary care has been established (1–3). The high percentage of presenting complaints of otolaryngology in primary care is only one indication of its importance. Surveys of PCPs also show that they value its importance in their clinical practice (6, 7). A survey of primary care physicians in Wisconsin showed that they ranked otolaryngology as the third most important surgical subspecialty, after general surgery and orthopedic surgery (6). These primary care physicians were board certified in family medicine, pediatric, and internal medicine. These respondents were asked to identify three areas in the clerkship's core curriculum perceived as the most critical for third-year medical students to learn based on their day-to-day clinical practice. A survey of primary care physicians in Kentucky showed that they ranked disorders of the ear, nose, and throat and airway obstruction as extremely important and relevant to their clinical practice (7). These respondents were provided a list of topics and asked to give their opinion on the relevance of these topics to their practice of medicine. Hence, these survey responses were based on the clinical needs of the patient population.

Despite the importance of otolaryngology in primary care, there is limited time for otolaryngology training for PCPs – among physician trainees, the first opportunity is in undergraduate medical school curricula. A survey of the content, structure, and quantity of otolaryngology training in Canadian medical schools showed that there is no standardized curriculum and also a large variation in the quantity of otolaryngology training that is offered (8). The amount of time ranged from 1 to 20 hours of otolaryngology instruction. Clerkship rotations are not uniformly offered and the length of placements is limited. Skills in otolaryngology are rarely tested. Surveys of undergraduate otolaryngology training in the United Kingdom have also been conducted (10, 11). Six of the 27 (22%) medical schools do not have a compulsory otolaryngology rotation. The average time spent with the otolaryngology department during medical school training is one and a half weeks. Forty-two percent of students do not have a formal assessment of their clinical skills or knowledge at the end of the otolaryngology rotations. This rather low emphasis on otolaryngic disease during undergraduate medical education contrasts with the 20–50% incidence of disease that these individuals will manage as practitioners.

The second opportunity for training among physicians is in postgraduate medical education. A survey of Canadian family medicine residents reported that 66.7% received very little classroom instruction and 75.6% received very little clinical otolaryngology instruction (12). This finding is supported by another Canadian study which showed that opportunities for formal education in otolaryngology in primary care residencies are rare (8). A survey in Ireland reported that were a small number of 3-month otolaryngology intern posts available, while one otolaryngology senior house officer post is reserved for a general practitioner in the country, and otolaryngology courses are variable (3). This study deemed the non-specialist postgraduate otolaryngology exposure to be inadequate.

A review of PubMed shows virtually no studies on otolaryngology training among NPs and PAs. This is likely an area that would benefit from further study.

An additional opportunity for training, potentially for all PCPs, is continuing medical education. There is a paucity of studies on CME in otolaryngology for PCPs. A survey of general practitioners (GP) in England showed that 75% would like further training in otolaryngology (13). Three-quarters of these GPs felt that their undergraduate training in otolaryngology was inadequate and almost half felt that their postgraduate training in otolaryngology was inadequate (13). Our study also showed that PCPs would like further training in otolaryngology: 91% of respondents would attend the otolaryngology update course again.

Our institution has a strong tradition in primary care with its residency program ranked number one in the country. The PCPs in our study were all very motivated to attend a CME course and may have self-identified weaknesses in their knowledge base. The results of the pre-course knowledge test were disappointing. Mean knowledge score out of a maximum score of 12 was 4.0±1.7 (33.3±14.0%) (n=37). The results were further sorted by specialty area, and again all categories scored poorly on the pre-knowledge test.

Primary care in the United States is also being delivered by allied health professionals, like PAs and NPs. According to the National Ambulatory Medical Survey conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2009, 55.4% of primary care physicians had at least one NP, PA, or certified midwife working with them (14). In contrast, the same survey showed that advanced practice clinicians (e.g., NPs and PAs) have a relatively limited role in ambulatory otolaryngology clinics (15). An estimated 38.6±3.7 million outpatient otolaryngology visits were studied in this survey. An advanced practice clinician was seen in only 6.3±2.0% of these otolaryngology visits. Among these visits, 1.7±0.9% saw a NP and 4.6±1.9% saw a PA (15).

A review of PubMed shows virtually no studies on specifically the otolaryngology training among NPs and PAs. In terms of their more general training, the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners states that NPs all complete a bachelor's degree in nursing (4 years) (16). NPs then proceed to more advanced, graduate training through a NP degree program (2–4 years), which may be a master's or doctorate degree. According to the American Academy of Physician Assistants, PAs undergo an educational program that is modeled after medical school curriculum, which includes a combination of classroom and clinical instruction (17). The average length of a PA program is 27 months. Most PA programs require at least 2 years of college courses and the vast majority award master's degrees. Since all PAs must practice medicine with physician supervision, the otolaryngology knowledge base of the supervising physician is also important in examining PA primary care management of otolaryngology complaints.

The knowledge test questions were designed for any primary care provider, including an allied health professional (NP or PA). Any primary care provider needs to know when to appropriately refer a patient to a specialist. For example, indications for common otolaryngic procedures, like tonsillectomy and ear tubes, and red flags, like a concern for nasopharyngeal cancer, are all appropriate knowledge for any primary care provider. We also performed subgroup analysis and found that the mean scores of the medical doctors were not significantly different from the allied health professionals.

The sample questions in Table 1 highlight some interesting observations. In the first question, only 20% of primary care physicians knew the indication for a tonsillectomy (total responses = 51). This finding is similar to a Canadian survey which reported that few family physicians were aware of acceptable indications of referral to an otolaryngologist for tonsillectomy (18). Despite the fact that the American Academy of Otolaryngology has recently published clinical practice guidelines for tonsillectomy (19), the majority of PCPs are still unaware. For the second question on indications for ear tubes, none of the PCPs answered it correctly. There are well established indications for myringotomies and tympanostomy tubes (20). The American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Academy of Family Physicians have published clinical practice guidelines for the management of acute otitis media (21). A Canadian survey asked otolaryngologists and family physicians to rate the importance of 46 otolaryngology topics. Both groups ranked management of acute otitis media as the most important (9). In our study, none of the PCPs answered this question correctly. For the third question, only 29% of the respondents answered this question correctly (total responses = 38). A unilateral effusion in an adult is a red flag for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. This concept is taught in otolaryngology and needs to be highlighted to PCPs.

This study is one of the few studies to actually test the otolaryngology knowledge base of PCPs. It shows that the pre-course knowledge base in otolaryngology at a CME course is quite low among PCPs. Previous surveys have shown that PCPs are aware of their need for CME in this area (3, 13). Carr et al. tested family medicine residents on their knowledge and skill in anterior nasal packing (9). Fifty percent of the residents had already faced this problem in clinical care; however, the residents had average scores of less than 30%. This study, though, tested residents still undergoing training and not practicing primary care physicians.

It should also be stressed that the field of science, and specifically otolaryngology, is continually changing. New clinical guidelines aimed at PCPs are constantly being published, like the recent tonsillectomy guidelines launched by the American Academy of Otolaryngology – Head & Neck Surgery in 2011 (19). New technologies are being introduced, like the bone anchored hearing aid and newer versions of the cochlear implant. Surgeons have innovated with new operations, like the world's first laryngeal transplant in 1998, and the innovations continue Therefore it is an obligation of the primary care provider to be abreast of these new developments and help to offer these new treatment options to the patient.

There are some limitations to our study. Our knowledge test was not a thoroughly validated test on otolaryngology knowledge. Two board certified otolaryngologists created it based on their clinical experiences and reviewed each other's questions; thus, the test only had construct validity. Our sample questions show that the questions are at a reasonable level for a PCPs and they examine important topics, like indications for tonsillectomy and ear tubes. Secondly, the PCPs all enrolled in an otolaryngology update course. They may have a self-assessed weakness in otolaryngology, and hence, sought CME. As a counter-argument, these PCPs were motivated enough to seek CME. Unmotivated PCPs who do not keep up with literature may have even weaker knowledge of otolaryngology and never present to a CME course. Lastly, a post course test was not performed. It is outside the scope of this study to determine if a CME intervention is effective in educating PCPs. Our objective was to assess the otolaryngology knowledge in this group. This is a direction for future study to determine if a CME intervention will increase short term knowledge of otolaryngology among PCPs.

In conclusion, there is a low level of otolaryngology knowledge among PCPs attending an otolaryngology update course. There is a need for otolaryngology education among PCPs. Limited exposure to otolaryngology in training has created an environment where CME is the next opportunity to train our PCPs. Furthermore, science continues to develop new treatment possibilities and that continuously demands knowledge development. As medical educators, we share a responsibility to educate our PCPs to deliver high quality, current otolaryngology care and to make appropriate referrals for patients outside of their scope of practice.

Footnotes

Presented at the American Academy of Otolaryngology – Head & Neck Surgery 2011 Annual Meeting, San Francisco, USA, on Tuesday, September 13, 2011.

Conflict of interest and funding

The authors have not received any funding or benefits from industry or elsewhere to conduct this study.

References

- 1.Griffiths E. Incidence of ENT problems in general practice. J R Soc Med. 1979;72:740–2. doi: 10.1177/014107687907201008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hannaford PC, Simpson JA, Bisset AF, Davis A, McKerrow W, Mills R. The prevalence of ear, nose and throat problems in the community: results from a national cross-sectional postal survey in Scotland. Fam Pract. 2005;22:227–33. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmi004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donnelly MJ, Quiraishi MS, McShane DP. ENT and general practice: a study of paediatric ENT problems seen in general practice and recommendations for general practitioner training in ENT in Ireland. Ir J Med Sci. 1995;164:209–11. doi: 10.1007/BF02967831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Domanski MC, Ashktorab S, Bielamowicz SA. Primary care perceptions of otolaryngology. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;143:337–40. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2010.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Medical Association. Truth in Advertising: 2008 and 2010 survey results. Available from: http://www.ama-assn.org/resources/doc/arc/tiasurvey.pdf [cited 16 June 2012]

- 6.Lewis BD, Leisten A, Arteaga D, Treat R, Brasel K, Redlich PN. Does the surgical clerkship meet the needs of practicing primary care physicians? WMJ. 2009;108:398–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spratt JS, Papp KK. Practicing primary care physicians’ perspectives on junior surgical clerkship. Am J Surg. 1997;173:231–3. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(97)89598-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wong A, Fung K. Otolaryngology in undergraduate medical education. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;38:38–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carr M, Brown D, Reznick R. Needs assessment for an undergraduate otolaryngology curriculum. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;120:865–8. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(99)70328-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mace A, Narula A. Survey of current undergraduate otolaryngology training in the United Kingdom. J Laryngol Otol. 2004;118:217–20. doi: 10.1258/002221504322928008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joshi J, Carrie S. A survey of undergraduate otolaryngology experience at Newcastle University Medical School. J Laryngol Otol. 2006;120:770–3. doi: 10.1017/S0022215106002131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glicksman JT, Brandt MG, Parr J, Fung K. Needs assessment of undergraduate education in otolaryngology among family medicine residents. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;37:668–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clamp PJ, Gunasekaran S, Pothier DD, Saunders MW. ENT in general practice: training, experience and referral rates. J Laryngol Otol. 2007;121:580–3. doi: 10.1017/S0022215106003495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park M, Cherry D, Decker SL. NCHS Data Brief No. 69. 2011. Nurse practitioners, certified nurse midwives, and physician assistants in physician offices; pp. 1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhattacharyya N. Involvement of physician extenders in ambulatory otolaryngology practice. Laryngoscope 2012. doi: 10.1002/lary.23274. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Academy of Nurse Practitioners. Position statement on nurse practitioner curriculum. Available from: http://www.aanp.org/AANPCMS2/AboutAANP/NPCurriculum.htm [cited 15 April 2012].

- 17.American Academy of Physician Assistants. What is a PA? Available from: http://www.aapa.org/the_pa_profession/what_is_a_pa.aspx [cited 15 April 2012]

- 18.Carr MM, Kolenda J, Clarke KD. Tonsillectomy: indications for referral by family physicians versus indications for surgery by otolaryngologists. J Otolaryngol. 1997;26:225–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baugh RF, Archer SM, Mitchell RB, Rosenfeld RM, Amin R, Burns JJ, et al. American Academy of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery. Clinical practice guideline: tonsillectomy in children. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;144(Suppl 1):S1–30. doi: 10.1177/0194599810389949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morris MS. Tympanostomy tubes: types, indications, techniques, and complications. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1999;32:385–90. doi: 10.1016/s0030-6665(05)70140-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.American Academy of Pediatrics Subcommittee on Management of Acute Otitis Media. Diagnosis and management of acute otitis media. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1451–65. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.5.1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]