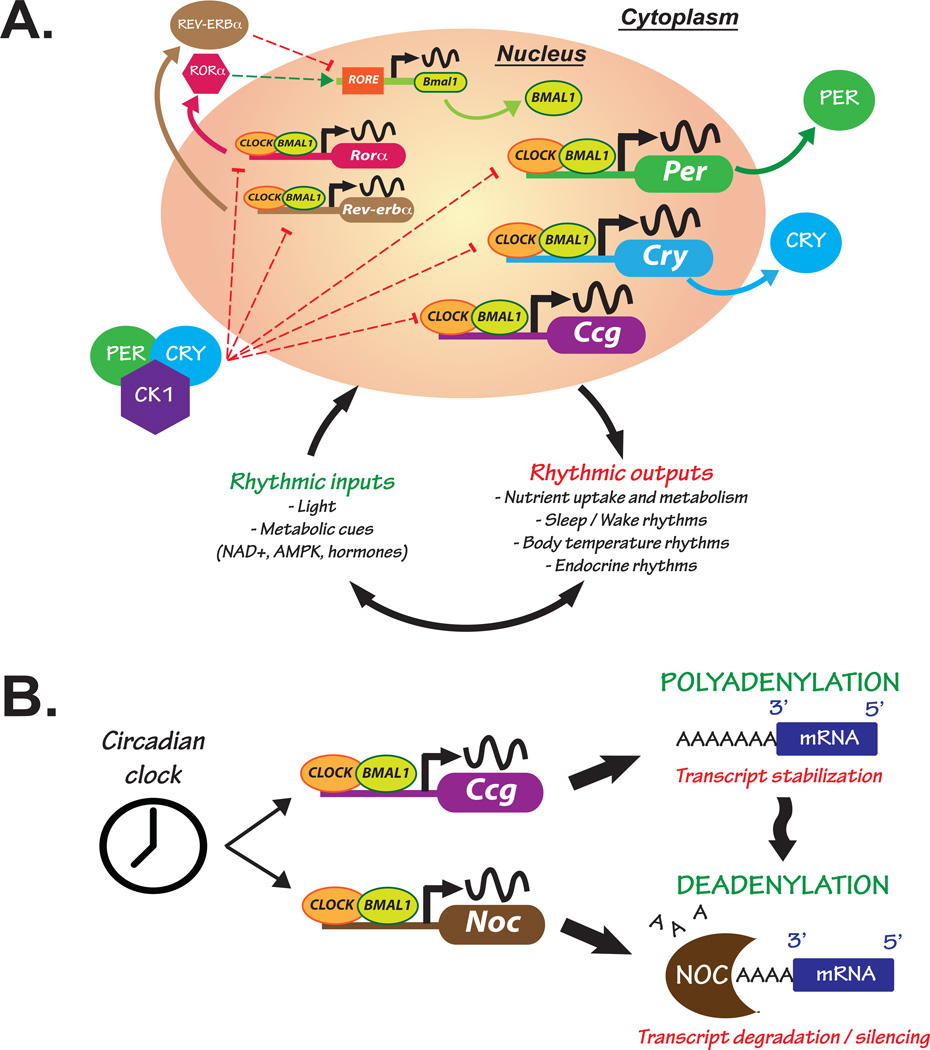

Figure 1. The molecular circadian clock is responsive to environmental and metabolic cues while maintaining tight control over gene expression.

(A) Cells from the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) within the brain receive external environmental (e.g. light) and internal (e.g. nutrients and hormones) cues that influence gene expression of core “clock” genes. The CLOCK/BMAL1 heterodimer binds to E-box enhancer elements in the promoter of core clock genes, such as Period (Per) and Cryptochrome (Cry), and other clock-controlled genes (Ccg) responsible for clock output. PER and CRY proteins accumulate in the cytoplasm where they complex with Casein Kinase 1 (CK1) and translocate back into the nucleus inhibiting their own transcription. Clock output is responsible for synchronizing rhythms in peripheral clocks and influencing processes such as rhythmic nutrient metabolism and uptake, and the sleep/wake and body temperature cycles. Nutrient signals (e.g. NAD+, AMPK) participate in crosstalk with the core clock by feeding back and influencing nuclear receptors such as Rev-erbα and the retinoic acid-related orphan receptor α (RORα), thus contributing to molecular rhythm generation. Positive and negative regulatory mechanisms are represented with green and red broken lines, respectively. (B) The circadian clock generates rhythms in gene expression, but post-transcriptional mechanisms such as deadenylation can also alter rhythmic mRNA processing. mRNA stability is maintained in part through polyadenylation, a process involving the addition of 3’ adenosine residues creating a polyA tail on messenger transcripts. Conversely, polyA tail removal through deadenylation leads to transcript degradation or silencing. The clock and metabolic cues influence rhythmic expression of the gene Nocturnin (Noc), encoding a circadian deadenylase. This could be one mechanism whereby the clock exerts tight control over expression of genes involved in nutrient metabolism through regulating post-transcriptional modifications.