Background: PCSK9 regulates cholesterol homeostasis by enhancing the LDLR protein degradation. The effects of PPARγ on PCSK9 and LDLR expression remain unknown.

Results: PPARγ activation by ligands or dephosphorylation induces PCSK9 and LDLR expression and cholesterol metabolism.

Conclusion: PPARγ is an important transcriptional factor in regulating PCSK9 and LDLR expression.

Significance: We define a new signaling pathway that regulates PCSK9 and LDLR expression.

Keywords: Cholesterol Metabolism, ERK, Lipoprotein Receptor, Phosphorylation, Peroxisome Proliferator-activated Receptor (PPAR), PCSK9

Abstract

Proprotein convertase subtilisin kexin type 9 (PCSK9) plays an important role in cholesterol homeostasis by enhancing the degradation of LDL receptor (LDLR) protein. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) has been shown to be atheroprotective. PPARγ can be activated by ligands and/or dephosphorylation with ERK1/2 inhibitors. The effect of PPARγ on PCSK9 and LDLR expression remains unknown. In this study, we investigated the effects of PPARγ on PCSK9 and LDLR expression. At the cellular levels, PPARγ ligands induced PCSK9 mRNA and protein expression in HepG2 cells. PCSK9 expression was induced by inhibition of ERK1/2 activity but inhibited by ERK1/2 activation. The mutagenic study and promoter activity assay suggested that the induction of PCSK9 expression by ERK1/2 inhibitors was tightly linked to PPARγ dephosphorylation. However, PPARγ activation by ligands or ERK1/2 inhibitors induced hepatic LDLR expression. The promoter assay indicated that the induction of LDLR expression by PPARγ was sterol regulatory element-dependent because PPARγ enhanced sterol regulatory element-binding protein 2 (SREBP2) processing. In vivo, administration of pioglitazone or U0126 alone increased PCSK9 expression in mouse liver but had little effect on PCSK9 secretion. However, the co-treatment of pioglitazone and U0126 enhanced both PCSK9 expression and secretion. Similar to in vitro, the increased PCSK9 expression by pioglitazone and/or U0126 did not result in decreased LDLR expression and function. In contrast, pioglitazone and/or U0126 increased LDLR protein expression and membrane translocation, SREBP2 processing, and CYP7A1 expression in the liver, which led to decreased total and LDL cholesterol levels in serum. Our results indicate that although PPARγ activation increased PCSK9 expression, PPARγ activation induced LDLR and CYP7A1 expression that enhanced LDL cholesterol metabolism.

Introduction

Serum cholesterol levels, and in particular low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL cholesterol) levels, are correlated with the incidence of coronary heart disease (1). Cholesterol homeostasis is determined by several factors, such as the digestion and absorption of cholesterol from the food sources, the biosynthesis of cholesterol in the liver, the utilization of cholesterol for basic metabolic processes, and the metabolism of cholesterol in the liver. As cholesterol is metabolized, liver cells absorb and internalize LDL cholesterol through the action of LDL receptor (LDLR).3 In the liver, free cholesterol is further metabolized into bile acids for excretion by action of a series enzymes including cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase (CYP7A1), the rate-limiting enzyme (2).

The LDLR is a cell surface glycoprotein that is responsible for the clearance of ∼70% of plasma LDL cholesterol in the human liver (2). In humans, LDLR mutations cause familial hypercholesterolemia, a common autosomal dominant disorder associated with the elevation of LDL cholesterol levels, the deposition of excess LDL cholesterol in the tendons and arteries, and the formation of tendon xanthomas and atherosclerotic plaques (3). Similar phenotypes are observed in mice with genetic deletions of LDLR when the animals are fed a Western diet (4). LDLR expression is activated by sterol regulatory element-binding protein 2 (SREBP2), a transcriptional factor that functions to reciprocate cellular sterol levels (2).

Proprotein convertase subtilisin kexin type 9 (PCSK9), a member of the subtilisin-like serine convertase superfamily, was first described as a protein that is important for liver regeneration and neuronal differentiation (5). In later studies, PCSK9 was recognized to play an important role in cholesterol homeostasis (6). The proform of PCSK9 is initially produced in the liver. After its initial synthesis, PCSK9 undergoes an intracellularly regulated autocatalytic cleavage that removes its N-terminal prodomain to promote the secretion of mature PCSK9 as a cleaved complex. This mature form of PCSK9 circulates and binds to the LDLR on the surface of cells to form an LDLR-PCSK9 complex, which then internalizes and directs the LDLR toward lysosomal degradation. Therefore, PCSK9 inhibits the expression of LDLR at a post-transcriptional level (7). Indeed, the overexpression of PCSK9 has little effect on LDLR mRNA levels (8). Several lines of evidence have shown the physiological importance of PCSK9. In humans, gain of function mutations of PCSK9, such as D347Y, increase the affinity of PCSK9 for LDLR, thereby further enhancing the degradation of the LDLR protein. Patients with such mutations are associated with familial hypercholesterolemia and an increased risk of cardiovascular disease (9, 10). In contrast, loss of function mutations that cause defects in the self-cleavage and secretion of PCSK9 (such as Y142X and C679X) result in hypocholesterolemia, which is associated with a reduced cardiovascular risk (11). In cases of patients with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia, loss of function mutations of PCSK9 lead to these patients responding particularly well to statin therapy (12).

Experiments in cultures of HepG2 cells have shown that exogenous treatment with purified PCSK9 protein reduces endogenous LDLR protein levels. In animal models, transgenic mice overexpressing human PCSK9 in the liver secrete a large amount of the protein into their plasma, thereby causing an increase in plasma LDL cholesterol concentrations similar to LDLR knock-out mice (7, 13). In contrast, the genetic deletion of PCSK9 (PCSK9−/−) expression leads to increased LDLR protein expression without affecting mRNA levels in mouse liver. This increase in LDLR protein stimulates the clearance of circulating LDL cholesterol and thereby reduces plasma LDL cholesterol levels. Furthermore, the administration of statins to PCSK9−/− mice produces an exaggerated increase in LDLR protein in the liver and clearance of LDL cholesterol from the plasma (14). Mice with a hepatocyte-specific knock-out of PCSK9 demonstrate reduced circulating total and LDL cholesterol levels. Single LDLR and double LDLR/PCSK9 knock-out mice exhibit similar cholesterol profiles, indicating that PCSK9 regulates cholesterol homeostasis exclusively through the LDLR (15). Selective inhibition of PCSK9 expression by injection of PCSK9 siRNA in lipidoid nanoparticles increases LDLR protein and reduces plasma total and LDL cholesterol levels in multiple species (16). A neutralizing anti-PCSK9 antibody has also been shown to have similar effects on hepatic LDLR protein and serum cholesterol levels (17).

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) belongs to the PPAR family of ligand-activated transcription factors (other isoforms include PPARα and PPARβ/δ) (18). PPARγ activation by ligands leads to the formation of heterodimers of PPARγ with the retinoid X receptor α. A complex of PPARγ and retinoid X receptor α then binds to the PPAR-responsive element (PPRE) of target gene promoters to activate their transcription. PPARγ plays an important role in different biological processes (18). PPARγ activation by synthetic thiazolidinedione ligands enhances insulin sensitivity and improves glycemic control. Some thiazolidinediones have been prescribed to treat patients with type 2 diabetes. PPARγ is expressed at high levels in macrophage/foam cells in lesions, which implicates the important role of PPARγ in the development of atherosclerosis. Indeed, thiazolidinediones have been reported to inhibit the development of atherosclerosis in animal models (19–22).

Although the functions of PPARγ in the cardiovascular system have been well investigated, it remains unknown whether PPARγ activation is able to influence PCSK9 expression. In addition, PPARγ can be phosphorylated by ERK1/2, and dephosphorylation of PPARγ by ERK1/2 inhibitors enhances PPARγ transcriptional activity (23–28). In this study, we investigated the effect of PPARγ activation by ligands or dephosphorylation with ERK1/2 inhibitors on hepatic PCSK9 expression both in vitro and in vivo. We also studied the effect of PPARγ activation on LDLR expression as well as cholesterol metabolism. Our study indicates that although PPARγ activation induces PCSK9 expression, it does not deteriorate LDL cholesterol metabolism.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents

15-deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2 (15d-PGJ2) and rabbit anti-PCSK9 polyclonal antibody were purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). Pioglitazone was kindly provided by Takeda Chemical Industries, Ltd. (Osaka, Japan). PD98059 and U0126 were purchased from LC Laboratories (Woburn, MA). Rabbit anti-PPARγ and anti-phospho-PPARγ polyclonal antibodies were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). Rabbit anti-LDLR and SREBP2 polyclonal antibodies were purchased from Novus Biologicals (Littleton, CO). All other chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich except as indicated.

Cell Culture

The human hepatic HepG2 cell line was purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA) and cultured in complete DMEM containing 10% FCS, 50 μg/ml of penicillin/streptomycin, and 2 mm glutamine. The cells at ∼90% confluence were switched into serum-free medium before the indicated treatment.

Determination of PCSK9, LDLR, SREBP2, PPARγ, and Phospho-PPARγ Protein Expression by Western Blot

After the indicated treatment, the cells were washed twice with PBS and lysed with a lysis buffer (20 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 137 mm NaCl, 2 mm EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 25 mm β-glycerophosphate, 2 mm sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 10 μg/ml aprotinin/leupeptin, and 100 mm NaVO4). The cellular lysate was spun for 10 min at 16,200 × g at 4 °C, and the supernatant was transferred to a new test tube. Proteins (80 μg) from each sample were separated on a 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and transferred onto a nylon-enhanced nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was blocked with a solution of 0.5% Tween 20/PBS (PBS-T) containing 5% nonfat dry milk for 2 h and then incubated with the indicated rabbit polyclonal primary antibody for 1 h at room temperature followed by washing three times for 10 min with PBS-T buffer. The blot was then reblocked for 1 h followed by the addition of horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG and incubation for 1 h at room temperature. After three washes with PBS-T (10 min each), the membrane was incubated for 5 min in a mixture of equal volumes of Western blot chemiluminescence reagents 1 and 2. The membrane was then exposed to film for development.

Isolation of Total Cellular RNA and Real Time PCR Analysis of Hepatic PCSK9, LDLR, and CYP7A1 mRNA Expression

After treatment, HepG2 cells were lysed, or a piece of the liver was homogenized in TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). The lysate or homogenate was well mixed with chloroform and spun for 10 min at 16,200 × g at 4 °C. The top aqueous phase, which contains RNA, was collected and mixed with isopropanol to precipitate the total RNA. The cDNA was then synthesized with 1 μg of total RNA using a reverse transcription kit purchased from New England Biolab (Ipswich, MA). Real time PCR was performed using a SYBR green PCR master mix from Bio-Rad with the primers in Table 1. Expression of PCSK9 mRNA in HepG2 cells or expression of LDLR and CYP7A1 mRNA in mouse liver was normalized to the corresponding GAPDH mRNA.

TABLE 1.

Sequences of primers for real time PCR

| Gene | Sense | Antisense |

|---|---|---|

| hPCSK9 | 5′-AGTTGCCCCATGTCGACTAC-3′ | 5′-GAGATACACCTCCACCAGGC-3′ |

| hGAPDH | 5′-GGTGGTCTCCTCTGACTTCAACA-3′ | 5′-GTTGCTGTAGCCAAATTCGTTGT-3′ |

| mLDLR | 5′-GAGGAACTGGCGGCTGAA-3′ | 5′-GTGCTGGATGGGGAGGTCT-3′ |

| mCYP7A1 | 5′-CAGGGAGATGCTCTGTGTTCA-3′ | 5′-AGGCATACATCCCTTCCGTGA-3′ |

| mGAPDH | 5′-ACCCAGAAGACTGTGGATGG-3′ | 5′-ACACATTGGGGGTAGGAACA-3′ |

Preparation of Plasmid DNA and Determination of PCSK9 and LDLR Promoter Activity

A cDNA encoding mouse PPARγ2 was generated by reverse transcription with total cellular RNA isolated from the differentiated 3T3-L1 adipocytes and an oligo(dT)18 primer followed by PCR with forward and backward primers: 5′-TCTCGAGCTCAATGGGTGAAACTCTGGGAG-3′ and 5′-CCGCGGTACCCTAATACAAGTCCTTGTAGATCTCCT-3′. After the sequence was confirmed, the PCR product was digested with SacI and KpnI and then subcloned into a pEGFP-C2 expression vector (C2-PPARγ2). The nonphosphorylated PPARγ2 (serine 112 is mutated to alanine, γS112A) and constitutively phosphorylated PPARγ2 (serine 112 is mutated to aspartate, γS112D) expression vectors were constructed using the Phusion site-directed mutagenesis kit from New England Biolabs with C2-PPARγ2 and primers with the corresponding mutated sequences.

The mouse PCSK9 promoter (from −829 to −1) was constructed by PCR with mouse genomic DNA and the following primers: forward, 5′-TGCACTCGAGCCAGCTTGTGCTTACGATG-3′ and backward, 5′-TGCCAAGCTTCGGGGCGAGGAGAGGTGCGC-3′. After the sequence was confirmed, the PCR product was digested with XhoI and HindIII followed by ligation with the pGL4 luciferase reporter vector (pPCSK9), and the product was then transformed into Escherichia coli to amplify. The promoter with the PPRE or DR1 mutation (pPCSK9-DR1mut) or deletion (pPCSK9-DR1del) was constructed using the Phusion site-directed mutagenesis kit with pPCSK9 DNA and primers with the corresponding DR1 deletion or mutation.

The mouse LDLR promoter (from −331 to +49) including the SRE (ATCACCCCAT, located from −213 to −204) was generated by PCR with mouse genomic DNA and the following primers: forward, 5′-TGCACTCGAGCTGTGGGAGGAATTTGAGGA-3′ and backward, 5′-TGCCAAGCTTAGGAGCAGGGCGATGAC-3′. After the sequence was confirmed, the PCR product was digested with XhoI and HindIII followed by ligation with the pGL4 luciferase reporter vector (pLDLR). The promoter with the SRE mutation (pLDLR-SREmut) was constructed with pLDLR DNA and primers with the corresponding SRE mutation: pLDLR SREmu-f, 5′-gaagatttttgaaaATCACGGCATtgcagactcctccccg-3′ [CC in SRE motif (underlined) was replaced by GG]; and pLDLR SREmu-r, 5′-ggggaggagtctgcaATGCCGTGATtttcaaaaatcttc-3′.

To analyze PCSK9 or LDLR promoter activity, ∼95% confluent 293T cells in 24-well plates were transfected with DNA encoding PCSK9 or LDLR promoter and Renilla (for internal normalization) using LipofectamineTM 2000 (Invitrogen). After 24 h of transfection and treatment, the cells were lysed, and the cellular lysate was used to determine the activities of the firefly and Renilla luciferases using the dual-luciferase reporter assay system from Promega (Madison, WI).

In Vivo Studies

The protocol for in vivo studies with mice was granted by the Ethics Committee of Nankai University and conforms with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the National Institutes of Health. Male wild type mice (C57BL/6, 8 weeks old) were divided into four groups (5 mice/group) and fed normal chow or chow containing U0126 (5 mg/100 g of food) or pioglitazone (30 mg/100 g of food) or pioglitazone plus U0126 ((30 mg of pioglitazone + 5 mg of U0126)/100 g of food). The animals had free to access to food and drinking water. After 10 days of treatment, the nonfasting animals were anesthetized and euthanized in a CO2 chamber. Blood was collected and kept for more than 2 h at room temperature. After centrifugation for 20 min at 2,000 × g at room temperature, the serum was transferred to a new test tube and kept at −20 °C until assay for the secretion of PCSK9 using an ELISA kit purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN) or lipid profiles including total, LDL, and HDL cholesterol levels with assay kits purchased from Wako Chemicals (Richmond, VA).

A piece of the liver (∼30 mg) from each mouse was collected and homogenized in a protein lysis buffer mentioned above. The homogenates were spun for 20 min at 16,200 × g at 4 °C. The supernatant, which contains the total cellular proteins, was collected and used to determine the expression of PCSK9, LDLR, and SREBP2 protein by Western blot.

Isolation of LDL and Analysis of LDL Binding to HepG2 Cells

LDL (1.019–1.063 g/ml) was isolated from normal human plasma by sequential ultracentrifugation. To conduct the binding of LDL to HepG2 cells, LDL was fluorescein conjugated with a reactive succinimidyl-ester of carboxyl-fluorescein using a labeling kit purchased from Princeton Separations (Adelphia, NJ). HepG2 cells were cultured in a 4-well slide chamber. After treatments, the cells were washed twice with PBS and then incubated with 30 μg/ml of labeled LDL in serum-free medium for 2 h at 37 °C. After being washed twice with PBS and covered by Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA), the cells were observed with a fluorescent microscope and photographed.

Immunohistochemical and Immunofluorescent Staining Analysis

After treatment and sacrifice, a piece of the liver was removed and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde followed by embedding in paraffin. To determine LDLR protein expression in the liver, 5-μm paraffin sections were collected and processed as follows; the sections were initially deparaffinized and hydrated. The antigen retrieval was obtained by heating the sections in a sodium citrate solution (0.01 m, pH 6.0) for 20 min in a 95 °C water bath. The sections were then blocked with goat serum for 15 min followed by incubation with rabbit anti-LDLR polyclonal antibody (1:100 dilution) overnight at 4 °C. After the removal of the primary antibody by washing with PBS, the sections were incubated with biotin-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG for 15 min at room temperature. After washing with PBS, the sections were incubated in a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated avidin solution for 20 min followed by adding the developing solution. After development, the sections were stained with hematoxylin solution for nucleus and then mounted under cover slides with Permount. After adequate drying, the slides were observed and photographed with a microscope.

To further determine the expression and membrane location of LDLR protein, the above liver sections after the antigen retrieval were blocked with 2% BSA for 2 h at room temperature followed by incubation with rabbit anti-LDLR polyclonal antibody (1:250 dilution) overnight at 4 °C. After removal of the primary antibody by washing with PBS for 30 min, the sections were incubated with TRITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:1000 dilution) for 2 h at room temperature. After washing with PBS for 30 min, the sections were stained with DAPI solution for nucleus. Images of the sections were obtained with a fluorescence microscope (Leica).

Data Analysis

All of the experiments were repeated at least three times, and the representative results were presented. The data were presented as the means ± standard deviation and analyzed using the paired Student's t test (n = 3 for promoter activity assay and real time PCR, n = 5 for serum lipid profiles assay, and n = 10 for serum PCSK9 ELISA). The significant difference was considered at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

PPARγ Ligands Induce PCSK9 Expression in HepG2 Cells

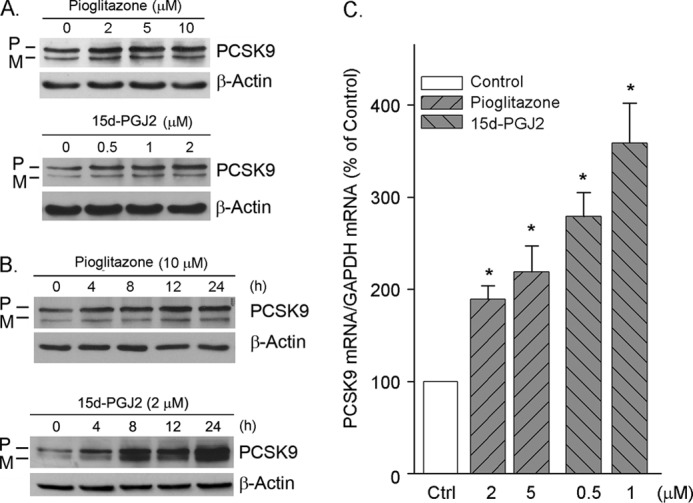

PCSK9 is mainly expressed and secreted from hepatocytes (6). To test whether the PPARγ activation is able to influence PCSK9 expression, confluent HepG2 cells in serum-free medium were treated with a natural PPARγ ligand (15d-PGJ2) or a synthetic PPARγ ligand (pioglitazone) at different concentrations overnight. The expression levels of PCSK9 protein were assessed by Western blot. Both the precursor and mature forms of PCSK9 were detectable. The results in Fig. 1A indicate that both the precursor and mature forms of PCSK9 protein were increased by PPARγ ligands, with a greater increase in precursor form indicating the stimulation of PCSK9 expression in HepG2 cells. We also performed a time course study and observed that the induction of PCSK9 expression occurred quickly after treatment, particularly in response to 15d-PGJ2. The maximal levels of induction were observed between 12 and 24 h after treatment (Fig. 1B).

FIGURE 1.

PPARγ ligands induce PCSK9 expression in HepG2 cells. A and B, confluent (∼95%) HepG2 cells in serum-free DMEM were treated with 15d-PGJ2 and pioglitazone at the indicated concentrations overnight (A) or treated with 15d-PGJ2 (2 μm) and pioglitazone (10 μm) for the indicated times (B). After treatment, the cellular proteins were extracted and used to determine both the precursor of PCSK9 (P) and mature PCSK9 (M) protein by Western blot as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The same membrane was reblotted with anti-β-actin antibody to verify equal loading. C, after extraction, the total cellular RNA was used to determine PCSK9 mRNA expression by real time PCR. *, significantly different from control (Ctrl) at p < 0.05 by the paired Student's t test (n = 3).

To study whether the induction of PCSK9 protein expression by PPARγ ligands is associated with an increase in PCSK9 mRNA expression, total cellular RNA was extracted after treatment and used to determine changes in PCSK9 mRNA by real time PCR. Consistent with PCSK9 protein expression, the results in Fig. 1C show that the PPARγ ligands increased PCSK9 mRNA expression. Thus, the induction of PCSK9 expression by PPARγ ligands can be attributed to an increase in PCSK9 transcription.

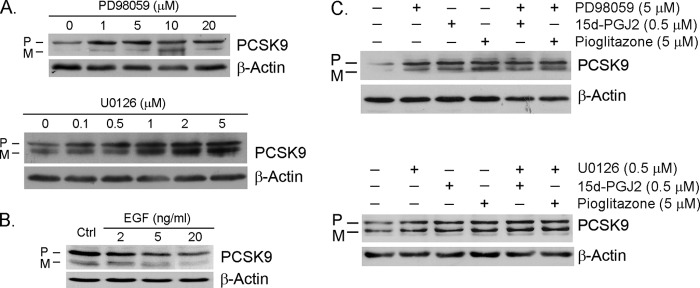

ERK1/2 Activity Influences PCSK9 Expression in HepG2 Cells by Regulating PPARγ Phosphorylation

The conserved substrate sequence for ERK1/2 in the PPARγ protein indicates that PPARγ can be phosphorylated by ERK1/2 to regulate its biological activity. In fact, dephosphorylation of PPARγ significantly increases PPARγ transcriptional activity (23–28). To determine whether PPARγ activation by dephosphorylation is also able to increase PCSK9 expression, we treated HepG2 cells with ERK1/2 inhibitors and determined the changes in PCSK9 protein levels. The results in Fig. 2A indicate that both PD98059 and U0126 induced PCSK9 expression in a concentration-dependent manner. In contrast to the effect of ERK1/2 inhibition, the activation of ERK1/2 by EGF resulted in a decrease in PCSK9 protein expression (Fig. 2B).

FIGURE 2.

Inhibition of ERK1/2 induces PCSK9 expression. A, HepG2 cells in serum-free medium were treated with PD98059 or U0126 at the indicated concentrations overnight. B, HepG2 cells were treated with EGF at the indicated concentrations overnight. C, HepG2 cells were treated with PD98059 (5 μm) or U0126 (0.5 μm) in the absence or presence of 15d-PGJ2 (0.5 μm) or pioglitazone (5 μm) overnight. Expression of PCSK9 was assessed by Western blot. Ctrl, control; P, precursor; M, mature.

PPARγ ligands and ERK1/2 inhibitors are both able to activate PPARγ to induce PCSK9 expression. To determine whether the co-treatment of ERK1/2 inhibitors and PPARγ ligands is able to induce PCSK9 expression in an additive manner, HepG2 cells were treated with PD98059 or U0126 in the presence or absence of 15d-PGJ2 or pioglitazone. Although ERK1/2 inhibitors or PPARγ ligands alone increased PCSK9 expression, their combination did not induce PCSK9 expression in an additive manner (Fig. 2C).

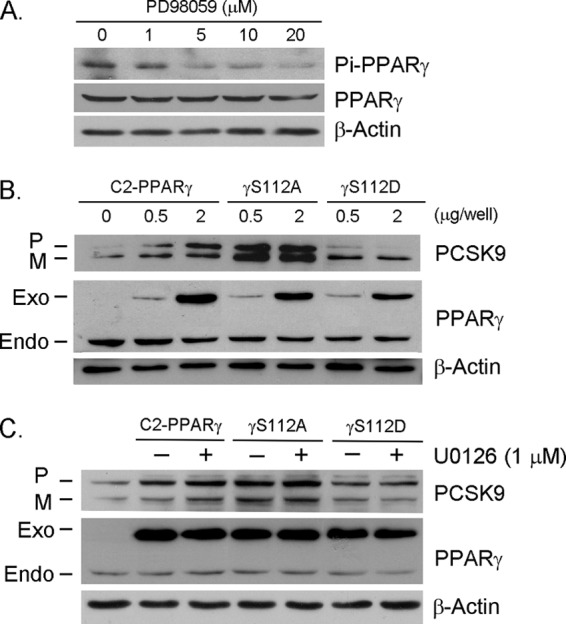

Several reports have shown that the phosphorylation of serine 112 on the PPARγ2 protein by ERK1/2 reduces its transcriptional activity, whereas the dephosphorylation of this serine enhances PPARγ function (25–28). Consistent with results showing that PPARγ activates by dephosphorylation upon treatment with ERK1/2 inhibitors, the mutation of serine 112 to alanine (PPARγS112A) abolishes PPARγ phosphorylation by ERK1/2, thereby resulting in increased PPARγ transcriptional activity (28). In contrast, compared with wild type PPARγ or PPARγS112A, the mutation of serine 112 to aspartate (PPARγS112D) results in constitutive PPARγ phosphorylation, thus significantly reducing PPARγ transcriptional activity (28). To further demonstrate that PPARγ activation by dephosphorylation induces PCSK9 expression, we first examined the changes in phospho-PPARγ protein levels in HepG2 cells after ERK1/2 inhibitor treatment. Fig. 3A demonstrates that PD98059 had little effect on PPARγ expression but significantly decreased phospho-PPARγ protein levels. We then constructed the following PPARγ expression vectors: wild type PPARγ (C2-PPARγ), nonphosphorylated PPARγ (mutation of serine 112 to alanine, γS112A), and constitutively phosphorylated PPARγ (mutation of serine 112 to aspartate, γS112D). We transfected HepG2 cells with these expression vectors and determined their effects on PCSK9 expression. The results in Fig. 3B indicate that the overexpression of wild type PPARγ increased PCSK9 expression. Compared with wild type PPARγ, the induction of PCSK9 expression was more by the nonphosphorylated PPARγ mutant (γS112A), and there was little effect by the constitutively phosphorylated PPARγ mutant (γS112D). As expected, the presence of ERK1/2 inhibitor, U0126, further enhanced the wild type PPARγ-induced PCSK9 expression but had little effect on the action of PPARγ mutants (Fig. 3C). Taken together, the results in Figs. 2 and 3 suggest that in addition to the ligands, PPARγ activation by dephosphorylation is also able to induce PCSK9 expression.

FIGURE 3.

Induction of PCSK9 expression by PPARγ dephosphorylation. A, HepG2 cells were treated with PD98059 at the indicated concentrations overnight. Expression of total PPARγ or phospho-PPARγ (Pi-PPARγ) was determined by Western blot with anti-PPARγ or anti-phospho-PPARγ antibody. B, HepG2 cells were transfected with expression vector of wild type PPARγ (C2-PPARγ) or nonphosphorylated PPARγ mutant (γS112A) or constitutively phosphorylated PPARγ mutant (γS112D) at the indicated concentrations overnight. C, HepG2 cells were transfected with expression vector of C2-PPARγ or γS112A or γS112D (0.5 μg/well of each). After 12 h of transfection, the cells were treated with U0126 (1 μm) overnight. Expression of PCSK9 and endogenous (Endo) and exogenous (Exo) PPARγ was determined by Western blot. P, precursor; M, mature.

Transcriptional Regulation of PCSK9 Expression by PPARγ Activation

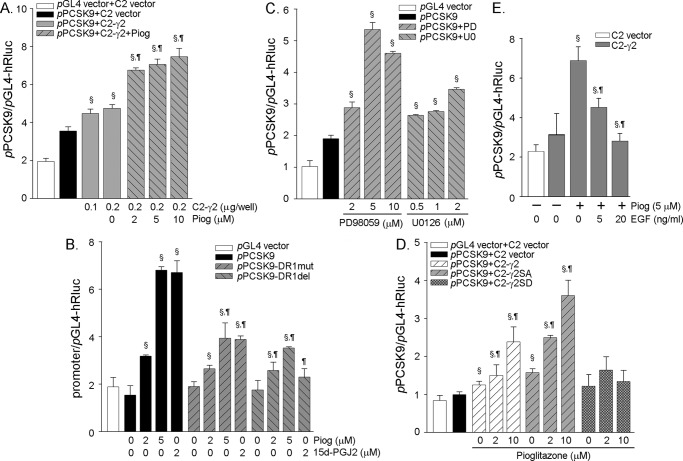

To determine whether the induction of PCSK9 expression by PPARγ activation occurs at the transcriptional level, we constructed a PCSK9 promoter (pPCSK9) and examined the effects of overexpressing PPARγ as well as PPARγ activation on the activity of PCSK9 promoter. As shown in Fig. 4A, the overexpressing PPARγ induced the activity of PCSK9 promoter, and this induction was further enhanced by a PPARγ ligand, pioglitazone.

FIGURE 4.

Regulation of PCSK9 promoter activity by PPARγ activation. All of the cells were transfected with DNA of Renilla luciferase for internal normalization. After transfection and treatment, the cellular lysate was extracted and used to determine activity of firefly and Renilla luciferases. A, 293T cells were transfected with DNA for the PCSK9 promoter and the PPARγ2 expression vector (C2-γ2, 0.2 μg/well) as indicated followed by treatment with pioglitazone (Piog) overnight. § and ¶, significantly different from the control (pPCSK9+C2 vector) and the sample of (pPCSK9+C2-γ2), respectively, at p < 0.05 by the paired Student's t test (n = 3). B, cells were transfected with DNA for wild type PCSK9 promoter (pPCSK9) or PCSK9 promoter with DR1 mutation (pPCSK9-DR1mut) or deletion (pPCSK9-DR1del) followed by treatment with pioglitazone or 15d-PGJ2 at the indicated concentrations overnight. § and ¶, significantly different from control (promoter alone) and the corresponding samples in the group of wild type promoter, respectively, at p < 0.05 (n = 3). C, cells were transfected with DNA for the PCSK9 promoter followed by treatment with PD98059 and U0126 at the indicated concentrations overnight. §, significantly different from the control (pPCSK9) at p < 0.05 (n = 3). D, cells were transfected with DNA for PCSK9 promoter and expression vector of wild type PPARγ (C2-γ2) or nonphosphorylated PPARγ mutant (C2-γ2SA) or constitutively phosphorylated PPARγ mutant (C2-γ2SD) followed by treatment with pioglitazone at the indicated concentrations overnight. § and ¶, significantly different from the sample of (pPCSK9+C2 vector) and the corresponding control (pPCSK9+C2-γ2 or pPCSK9+C2-γ2SA), respectively, at p < 0.05 (n = 3). E, cells were transfected with DNA for the PCSK9 promoter and the PPARγ expression vector followed by treatment with pioglitazone or pioglitazone plus EGF at the indicated concentrations overnight. § and ¶, significantly different from the control (C2-γ2) and the pioglitazone-treated sample (C2-γ2 + pioglitazone (5 μm), respectively, at p < 0.05 (n = 3).

Through the sequence alignment analysis, we found a putative PPRE in the PCSK9 promoter. (The sequence of the putative PPRE in the PCSK9 gene is GAGTCAtGGGTCA (from −565 to −553). The classic sequence of the PPRE is AGGTCAxAGGTCA. The PPRE is also named as direct repeat 1 (DR1) for its repeated hexanucleotides that are separated by one of any nucleotide.) To test the role of this putative PPRE in PCSK9 gene transcription, we also constructed mutant PCSK9 promoter with this PPRE or DR1 mutation (pPCSK9-DR1mut) or deletion (pPCSK9-DR1del) and compared the activities of the wild type and the mutant PCSK9 promoters. Although there was no significant difference in the basal levels among these promoters, the induction of these promoters activities by PPARγ activation was reduced by DR1 mutation or deletion, indicating the critical role of the PPRE in PCSK9 transcription (Fig. 4B). PCSK9 promoter with DR1 mutation or deletion was still activated by PPARγ activation at a lesser degree than that with wild type PCSK9 promoter was due to the existence of SRE in the promoter. Our further study demonstrated that PPARγ activation enhanced SREBP2 processing (Fig. 5; see Fig. 7). Similar to a ligand, PPARγ activation by dephosphorylation with ERK1/2 inhibitors also increased PCSK9 promoter activity, further suggesting a role for transcriptional induction (Fig. 4C). Consistent with the changes in PCSK9 protein expression, the PCSK9 promoter activity was increased by the wild type PPARγ and PPARγS112A but was not much affected by PPARγS112D (Fig. 4D). In contrast to the ERK1/2 inhibitors, EGF, an ERK1/2 activator, reduced PCSK9 promoter activity (Fig. 4E).

FIGURE 5.

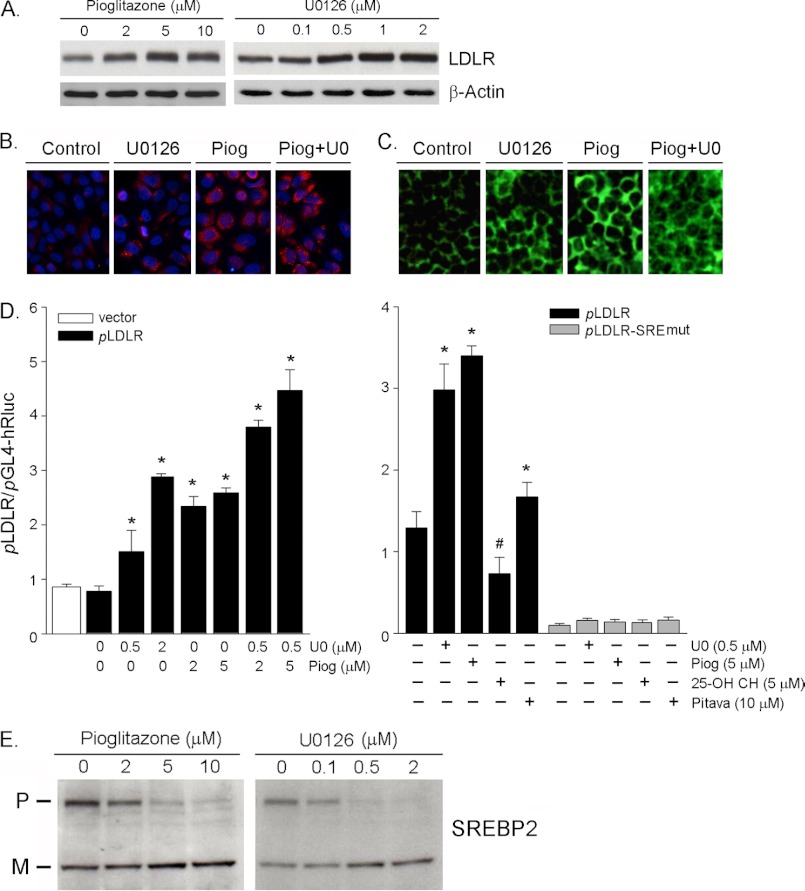

PPARγ activation induces LDLR expression and binding of LDL to HepG2 cells. A, HepG2 cells in serum-free medium were treated with pioglitazone (Piog) or U0126 at the indicated concentrations overnight. Expression of LDLR protein was determined by Western blot. B and C, HepG2 cells were treated with U0126 (1 μm) or pioglitazone (5 μm) or their combination overnight. The cells were then used to determine LDLR protein expression or uptake of LDL as described under “Experimental Procedures.” D, 293T cells were transfected with DNA for wild type LDLR promoter (pLDLR) or promoter with SRE mutation (pLDLR-SREmut). After 4 h of transfection, the cells received the indicated treatment overnight. 25-Hydroxycholesterol or pitavastatin was used as a negative or positive control. * and #, significantly different from control in the corresponding group at p < 0.05 (n = 3). E, HepG2 cells were treated with pioglitazone or U0126 at the indicated concentrations overnight. Whole cellular protein was extracted and used to determine the precursor and mature forms of SREBP2 by Western blot. P, precursor; M, mature.

FIGURE 7.

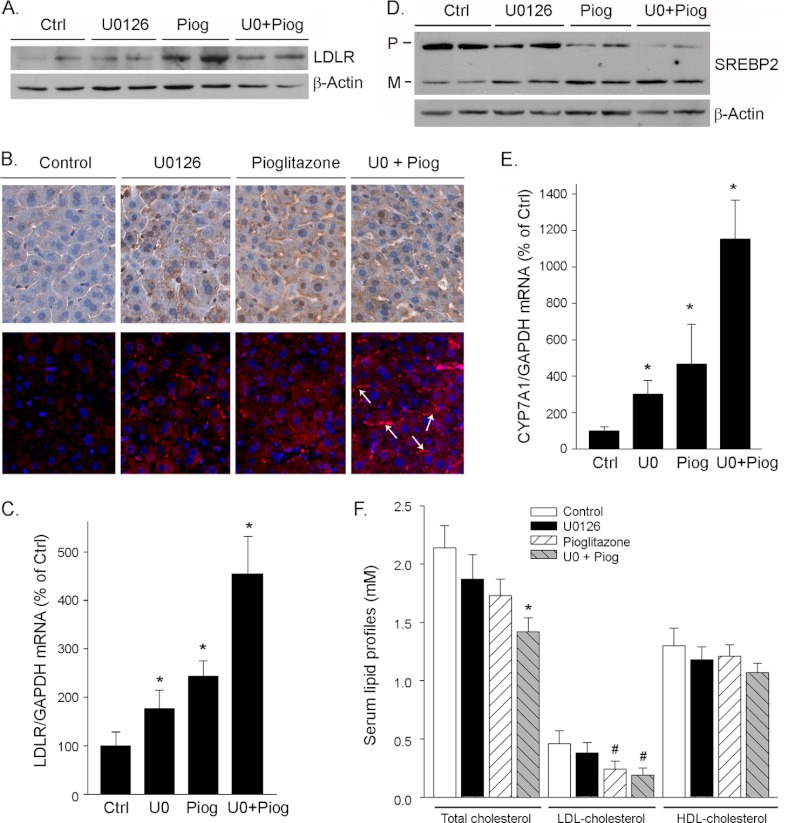

PPARγ activation induces expression of LDLR and 2CYP7A1 in mouse liver and reduces serum total and/or LDL cholesterol levels. The mice received the treatment as described in the legend to Fig. 6. Both liver and serum samples were collected and used for the following assays. A and D, expression of LDLR and SREBP2 protein in the liver was determined by Western blot. B, mouse liver sections were prepared and used to determine LDLR protein expression by immunohistochemical or immunofluorescent staining assay as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The arrows indicate the membrane location of LDLR protein. C and E, expression of LDLR and CYP7A1 mRNA in mouse liver was determined by real time PCR. *, significantly different from control (Ctrl) in the corresponding group at p < 0.05 (n = 5). F, serum lipid profiles were determined by enzymatic methods. * and #, significantly different from the corresponding control at p < 0.05 (n = 5). Piog, pioglitazone; P, precursor; M, mature.

PPARγ Activation Induces LDLR Expression in HepG2 Cells

PCSK9 reduces LDLR expression at a post-transcriptional level by enhancing LDLR protein degradation thereby deteriorating LDL cholesterol metabolism. To determine whether the induction of PCSK9 expression by PPARγ activation impacts hepatic LDLR expression, we treated HepG2 cells with pioglitazone or U0126 at different concentrations and assessed the changes in LDLR protein by Western blot. The results in Fig. 5A indicate that both pioglitazone and U0126 increased LDLR protein expression. To further confirm the inductive effect of PPARγ activation on LDLR expression, after treatment, we detected LDLR protein using an immunofluorescent staining assay. The results in Fig. 5B demonstrate that pioglitazone or U0126 alone increased LDLR expression. The increase was further enhanced by the co-treatment. Associated with the increased LDLR protein expression, the binding of LDL to the cells was also increased as the changes in LDLR protein (Fig. 5C).

PPARγ activation induces PCSK9 and LDLR expression simultaneously, suggesting that the induction of LDLR must be completed through a PCSK9-independent pathway, at least at the transcriptional level. To test whether the induction of LDLR expression by PPARγ activation is at the transcriptional level, we constructed a wild type LDLR promoter. Consistent with the effect on LDLR protein expression, the left panel of Fig. 5D indicates that pioglitazone or U0126 alone increased LDLR promoter activity, and the co-treatment further increased it. Interestingly, the SRE mutation abolished the induction of LDLR promoter activation, indicating that the induction of LDLR transcription by PPARγ activation is SRE-dependent. Therefore, we assessed the effect of pioglitazone and U0126 on the processing of SREBP2, the transcriptional factor regulating LDLR transcription. As expected, both pioglitazone and U0126 increased the mature SREBP2 (active form) while reducing the precursor of SREBP2 (inactive form), suggesting that PPARγ activation enhances SREBP2 processing.

PPARγ Activation Induces PCSK9 and LDLR Expression in Vivo

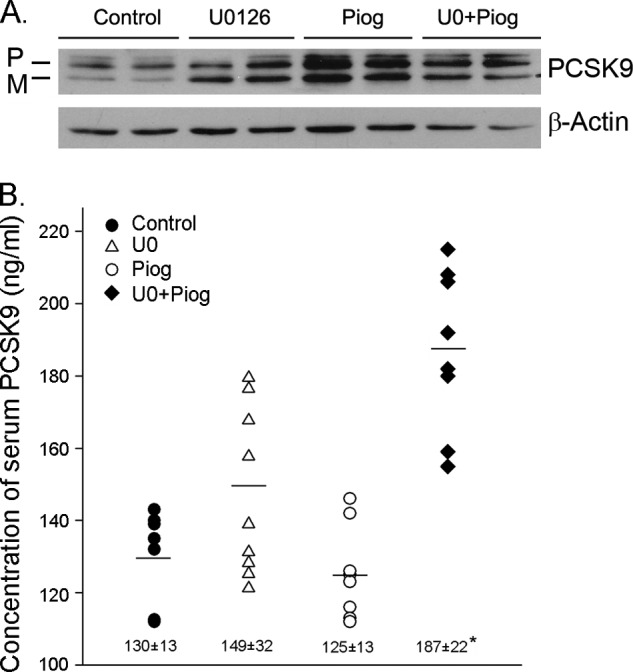

To determine the physiological relevance of the PPARγ activation on PCSK9 expression and secretion, wild type C57 mice were fed normal chow or chow containing U0126 or pioglitazone alone or U0126 plus pioglitazone for 10 days. Compared with the control mice, all of the treatment did not show any negative effect, such as the food intake and weight gain, to mice. After treatment, the expression of PCSK9 protein in the liver was assessed by Western blot. Similar to the in vitro studies, the administration of U0126 or pioglitazone alone increased PCSK9 protein expression, and the co-administration of U0126 and pioglitazone did not show an additive effect on the induction of PCSK9 protein expression in mouse liver (Fig. 6A). The concentration of mature PCSK9 in mouse serum was determined by ELISA, and the results in Fig. 6B indicate that pioglitazone or U0126 alone had little effect, whereas their co-administration increased the secretion of PCSK9.

FIGURE 6.

PPARγ activation increases PCSK9 production in vivo. Male wild type C57 mice (n = 5) were fed normal chow or chow containing U0126 (5 mg/100 g of food) or pioglitazone (Piog, 30 mg/100 g of food) or U0126 plus pioglitazone for 10 days. After treatment, mouse liver and serum samples were prepared. A, expression of PCSK9 protein in mouse liver was determined by Western blot. B, serum PCSK9 was determined by ELISA. *, significantly different from control at p < 0.05 (n = 10, each serum sample was analyzed twice). P, precursor; M, mature.

To determine whether the induction of PCSK9 expression by PPARγ activation influences LDLR expression and serum lipid profiles, we initially assessed LDLR protein levels in the liver by Western blot. Similar to the results in vitro study, although PPARγ activation increased PCSK9 expression, it induced LDLR protein expression simultaneously in the liver (Fig. 7A). The induction of LDLR protein expression either by pioglitazone or U0126 alone or their co-treatment was further confirmed by an immunohistochemical analysis (Fig. 7B, top panels). In addition, the immunofluorescent staining analysis suggested that the co-treatment enhanced the membrane translocation of LDLR protein (Fig. 7B, bottom panels, arrows). Associated with the increased LDLR protein, the results in real time PCR analysis demonstrate that PPARγ activation also induced LDLR transcription in vivo (Fig. 7C). The induction of LDLR expression by PPARγ activation was due to the enhancement of SREBP2 processing (Fig. 7D). In addition, we determined the effect of PPARγ activation on the expression of cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase (CYP7A1), the rate-limiting enzyme for cholesterol metabolism. We observed that pioglitazone or U0126 alone increased CYP7A1 mRNA expression, and the increase was further enhanced by the co-treatment. The induction of LDLR and CYP7A1 expression in the liver by PPARγ activation would lead to the enhanced LDL cholesterol metabolism. Indeed, the determination of serum profiles suggested that PPARγ activation, particularly by the co-treatment of pioglitazone and U0126, reduced serum total and LDL cholesterol levels (Fig. 7F).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we show that the PPARγ activation by ligands and dephosphorylation with ERK1/2 inhibitors increases PCSK9 expression. The induction of PCSK9 expression by PPARγ activation is PPRE-dependent. Although PPARγ activation induces PCSK9 expression, it does not decrease LDLR protein levels. In contrast, both in vitro and in vivo studies demonstrate that PPARγ activation induces hepatic LDLR expression in a SRE-dependent pathway and enhances the LDLR functions, such as the increased LDL uptake by HepG2 cells and reduced LDL cholesterol levels in serum. In addition to the induction of LDLR expression/function, PPARγ activation also induces CYP7A1 expression. Taken together, PPARγ activation, particularly by the co-treatment of ligand and ERK1/2 inhibitor, results in improved LDL cholesterol metabolism. Although we cannot conclude that a drug-mediated inhibition of PCSK9 expression will be accompanied by a decrease in LDLR expression, our study does suggest that the expression of PCSK9 does not have a dominant effect on LDLR expression or circulating LDL cholesterol levels. Our study indicates that LDLR expression is regulated by multiple signaling pathways and that some of these pathways are able to regulate PCSK9 expression simultaneously. Considering our results in combination with those of previous studies characterizing the regulation of PCSK9 and LDLR expression by other pathways, such as SREBP2 and PPARα, further work is required to discover the specific pathway that solely controls PCSK9 expression that could serve as a target for PCSK9 inhibition and LDL cholesterol reduction.

PCSK9 has been shown to play a critical role in cholesterol homeostasis by enhancing the degradation of the LDLR protein (6). The association of loss of function mutations with hypocholesterolemia and gain of function mutations with hypercholesterolemia in patients strongly supports a physiological role for PCSK9 expression/processing in the regulation of cholesterol levels (9–11). The inhibition of either PCSK9 expression or maturation causes a reduction of LDLR protein degradation and a consequent decrease in circulating LDL cholesterol levels. Thus, PCSK9 has been an interesting potential target for cholesterol-lowering drugs for the past several years.

These intensive studies have disclosed that a few transcriptional factors play important roles in the regulation of PCSK9 expression. The two typical conserved motifs for cholesterol regulation, the SRE and the Spi1-binding sites existing in the PCSK9 promoter, indicate the importance of SREBP in the regulation of PCSK9 gene transcription. In vitro, PCSK9 expression in HepG2 cells is completely dependent on cellular sterol levels. The absence of sterols in culture medium leads to the binding of SREBP to SRE and the activation of PCSK9 transcription. In animal models, although fasting decreases, whereas the refeeding increases PCSK9 expression in mouse liver, supplementing the diet with cholesterol prevents the increase of PCSK9 expression (29). Statins, a class of cholesterol-lowering medications, increase the activity/nuclear translocation of SREBP2, thereby activating PCSK9 transcription. The administration of statins increases PCSK9 protein levels in both normal and hypercholesterolemic subjects (30–32). The inductive effect of statins on PCSK9 expression is also confirmed by studies with animal models (14, 33). Statins substantially reduce circulating LDL cholesterol levels by inhibiting HMG-CoA reductase (the rate-limiting enzyme for cholesterol biosynthesis) to reduce the cholesterol biosynthesis and by activating LDLR expression to enhance the metabolism of LDL cholesterol in the liver simultaneously. However, statins also increase PCSK9 protein levels in a dose-dependent fashion. The increased PCSK9 levels largely negate the further statin-induced increases in hepatic LDLR levels that results in failure of increasing doses of statins to achieve proportional LDL cholesterol lowering effects. Indeed, statins typically follow a “6% rule,” because the reduction of LDL cholesterol achieved by a starting dose of a given statin is only improved ∼6% with each doubling of the dose (34).

PPARα is another transcriptional factor involved in the regulation of PCSK9 expression. However, the effects of PPARα on PCSK9 expression are controversial. At the cellular level, PPARα activation counteracts statin-induced PCSK9 expression by repressing PCSK9 promoter activity and by increasing PC5/6A and furin expression (PC5/6A and furin are proprotein convertases that inactivate PCSK9 protein) (35, 36). In statin-treated type 2 diabetic patients, fenofibrate decreases serum PCSK9 levels, and this reduction is correlated with decreases in total and small VLDL particle concentrations (37). Berberine, an isoquinoline plant alkaloid, induces LDLR expression at both the transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels. A reduction in hepatocyte nuclear factor 1α expression and nuclear SREBP2 and PPARα activation are believed the mechanisms by which berberine inhibits PCSK9 expression (38, 39). In contrast, administration of bezafibrate and fenofibrate to dyslipidemic subjects with impaired glucose tolerance or type 2 diabetes mellitus increases serum PCSK9 levels (40). In addition, fenofibrate and atorvastatin increased plasma PCSK9 in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and atherogenic dyslipidemia in a nonadditive fashion (41, 42).

To our knowledge, our study is the first demonstration that PCSK9 expression is induced by PPARγ activation with ligands and dephosphorylation. The existence of a conserved ERK1/2 site on PPARγ indicates that PPARγ can be phosphorylated. Many reports suggest that PPARγ dephosphorylation by chemicals or mutation enhances, whereas constitutive PPARγ phosphorylation by mutation reduces PPARγ transcriptional activity such as those required for adipogenesis and lipid metabolism in macrophages (23–28). Thiazolidinediones, the synthetic PPARγ ligands, have been shown to inhibit the development of atherosclerosis in animal models (19–22). In our study, PPARγ activation by pioglitazone and U0126 increases PCSK9 expression in the liver but has little effect on PCSK9 secretion. The co-administration of pioglitazone and U0126 induces the expression and secretion of PCSK9 (Fig. 6). The increased levels of circulating PCSK9 have been hypothesized to result from PCSK9 expression to such an extent that the PCSK9 in serum exceeds LDLR binding (31, 34). However, the increased expression/secretion of PCSK9 by this co-administration does not increase levels of serum total and LDL cholesterol. In contrast, both the total and LDL cholesterol levels are decreased (Fig. 7F). In addition, compared with the control, the ratio of HDL cholesterol levels to LDL cholesterol levels is increased by pioglitazone or pioglitazone plus U0126 (this ratio is 2.8 in control and ∼5 in groups of pioglitazone or pioglitazone plus U0126), indicating an improvement in LDL cholesterol metabolism. PPARγ activation also induces LDLR expression while increasing PCSK9 expression (Figs. 5 and 7). The inductive effect of PPARγ on LDLR expression depends on its function on the SREBP2 processing. Such induction should be in an extent that exceeds the inhibition of LDLR expression by the PPARγ-induced PCSK9. In combination with the induction of CYP7A1 expression (Fig. 7E), PPARγ activation by ligand plus ERK1/2 inhibitor results in decreased serum total and LDL cholesterol levels (Fig. 7F). The enhancement of SREBP2 processing by PPARγ activation also contributes to the PPARγ-induced PCSK9 expression because we still observed the inductive effect on the activity of PCSK9 promoters with PPRE/DR1 mutation and deletion (Fig. 4B). Therefore, our study indicates the complication in cholesterol homeostasis by regulating PCSK9 and LDLR expression, and SREBP2 may still also play a central role in PPARγ-mediated PCSK9 and LDLR expression, just as in the treatment with statins.

This work was supported by Ministry of Science and Technology of China Grants 2010CB945003 and 2009 DFB30560 (to J. H.), National Science Foundation of China Grants 30971271 (to J. H.) and 81000128 (to Y. D.), and Tianjin Municipal Science and Technology Commission of China Grants 08ZCKFSH04400, 2009ZCZDSF04200, and 11JCYBJC10600 (to J. H.).

- LDLR

- LDL receptor

- CYP7A1

- cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase

- PCSK9

- proprotein convertase subtilisin kexin type 9

- PPARγ

- peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ

- SRE

- sterol regulatory element

- SREBP2

- SRE-binding protein 2

- PPRE

- PPAR-responsive element

- TRITC

- tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate

- DR1

- direct repeat 1.

REFERENCES

- 1. Nordestgaard B. G., Chapman M. J., Ray K., Borén J., Andreotti F., Watts G. F., Ginsberg H., Amarenco P., Catapano A., Descamps O. S., Fisher E., Kovanen P. T., Kuivenhoven J. A., Lesnik P., Masana L., Reiner Z., Taskinen M. R., Tokgözoglu L., Tybjærg-Hansen A., and European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel (2010) Lipoprotein(a) as a cardiovascular risk factor: current status. Eur. Heart J. 31, 2844–2853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Defesche J. C. (2004) Low-density lipoprotein receptor. Its structure, function, and mutations. Semin. Vasc. Med. 4, 5–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. van Aalst-Cohen E. S., Jansen A. C., de Jongh S., de Sauvage Nolting P. R., Kastelein J. J. (2004) Clinical, diagnostic, and therapeutic aspects of familial hypercholesterolemia. Semin. Vasc. Med. 4, 31–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ishibashi S., Goldstein J. L., Brown M. S., Herz J., Burns D. K. (1994) Massive xanthomatosis and atherosclerosis in cholesterol-fed low density lipoprotein receptor-negative mice. J. Clin. Invest. 93, 1885–1893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Seidah N. G., Benjannet S., Wickham L., Marcinkiewicz J., Jasmin S. B., Stifani S., Basak A., Prat A., Chretien M. (2003) The secretory proprotein convertase neural apoptosis-regulated convertase 1 (NARC-1). Liver regeneration and neuronal differentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 928–933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Soutar A. K. (2011) Unexpected roles for PCSK9 in lipid metabolism. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 22, 192–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Park S. W., Moon Y. A., Horton J. D. (2004) Post-transcriptional regulation of low density lipoprotein receptor protein by proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9a in mouse liver. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 50630–50638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Maxwell K. N., Breslow J. L. (2004) Adenoviral-mediated expression of Pcsk9 in mice results in a low-density lipoprotein receptor knockout phenotype. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 7100–7105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Abifadel M., Varret M., Rabès J. P., Allard D., Ouguerram K., Devillers M., Cruaud C., Benjannet S., Wickham L., Erlich D., Derré A., Villéger L., Farnier M., Beucler I., Bruckert E., Chambaz J., Chanu B., Lecerf J. M., Luc G., Moulin P., Weissenbach J., Prat A., Krempf M., Junien C., Seidah N. G., Boileau C. (2003) Mutations in PCSK9 cause autosomal dominant hypercholesterolemia. Nat. Genet. 34, 154–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Allard D., Amsellem S., Abifadel M., Trillard M., Devillers M., Luc G., Krempf M., Reznik Y., Girardet J. P., Fredenrich A., Junien C., Varret M., Boileau C., Benlian P., Rabès J. P. (2005) Novel mutations of the PCSK9 gene cause variable phenotype of autosomal dominant hypercholesterolemia. Hum. Mutat. 26, 497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cohen J. C., Boerwinkle E., Mosley T. H., Jr., Hobbs H. H. (2006) Sequence variations in PCSK9, low LDL, and protection against coronary heart disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 354, 1264–1272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Berge K. E., Ose L., Leren T. P. (2006) Missense mutations in the PCSK9 gene are associated with hypocholesterolemia and possibly increased response to statin therapy. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 26, 1094–1100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lagace T. A., Curtis D. E., Garuti R., McNutt M. C., Park S. W., Prather H. B., Anderson N. N., Ho Y. K., Hammer R. E., Horton J. D. (2006) Secreted PCSK9 decreases the number of LDL receptors in hepatocytes and in livers of parabiotic mice. J. Clin. Invest. 116, 2995–3005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rashid S., Curtis D. E., Garuti R., Anderson N. N., Bashmakov Y., Ho Y. K., Hammer R. E., Moon Y. A., Horton J. D. (2005) Decreased plasma cholesterol and hypersensitivity to statins in mice lacking Pcsk9. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 5374–5379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zaid A., Roubtsova A., Essalmani R., Marcinkiewicz J., Chamberland A., Hamelin J., Tremblay M., Jacques H., Jin W., Davignon J., Seidah N. G., Prat A. (2008) Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9). Hepatocyte-specific low-density lipoprotein receptor degradation and critical role in mouse liver regeneration. Hepatology 48, 646–654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Frank-Kamenetsky M., Grefhorst A., Anderson N. N., Racie T. S., Bramlage B., Akinc A., Butler D., Charisse K., Dorkin R., Fan Y., Gamba-Vitalo C., Hadwiger P., Jayaraman M., John M., Jayaprakash K. N., Maier M., Nechev L., Rajeev K. G., Read T., Röhl I., Soutschek J., Tan P., Wong J., Wang G., Zimmermann T., de Fougerolles A., Vornlocher H. P., Langer R., Anderson D. G., Manoharan M., Koteliansky V., Horton J. D., Fitzgerald K. (2008) Therapeutic RNAi targeting PCSK9 acutely lowers plasma cholesterol in rodents and LDL cholesterol in nonhuman primates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 11915–11920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chan J. C., Piper D. E., Cao Q., Liu D., King C., Wang W., Tang J., Liu Q., Higbee J., Xia Z., Di Y., Shetterly S., Arimura Z., Salomonis H., Romanow W. G., Thibault S. T., Zhang R., Cao P., Yang X. P., Yu T., Lu M., Retter M. W., Kwon G., Henne K., Pan O., Tsai M. M., Fuchslocher B., Yang E., Zhou L., Lee K. J., Daris M., Sheng J., Wang Y., Shen W. D., Yeh W. C., Emery M., Walker N. P., Shan B., Schwarz M., Jackson S. M. (2009) A proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 neutralizing antibody reduces serum cholesterol in mice and nonhuman primates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 9820–9825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Brown J. D., Plutzky J. (2007) Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors as transcriptional nodal points and therapeutic targets. Circulation 115, 518–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Levi Z., Shaish A., Yacov N., Levkovitz H., Trestman S., Gerber Y., Cohen H., Dvir A., Rhachmani R., Ravid M., Harats D. (2003) Rosiglitazone (PPARγ-agonist) attenuates atherogenesis with no effect on hyperglycaemia in a combined diabetes-atherosclerosis mouse model. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 5, 45–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Li A. C., Brown K. K., Silvestre M. J., Willson T. M., Palinski W., Glass C. K. (2000) Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ ligands inhibit development of atherosclerosis in LDL receptor-deficient mice. J. Clin. Invest. 106, 523–531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Calkin A. C., Forbes J. M., Smith C. M., Lassila M., Cooper M. E., Jandeleit-Dahm K. A., Allen T. J. (2005) Rosiglitazone attenuates atherosclerosis in a model of insulin insufficiency independent of its metabolic effects. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 25, 1903–1909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Collins A. R., Meehan W. P., Kintscher U., Jackson S., Wakino S., Noh G., Palinski W., Hsueh W. A., Law R. E. (2001) Troglitazone inhibits formation of early atherosclerotic lesions in diabetic and nondiabetic low density lipoprotein receptor-deficient mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 21, 365–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Han J., Hajjar D. P., Tauras J. M., Feng J., Gotto A. M., Jr., Nicholson A. C. (2000) Transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) and TGF-β2 decrease expression of CD36, the type B scavenger receptor, through mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphorylation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 1241–1246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Han J., Hajjar D. P., Zhou X., Gotto A. M., Jr., Nicholson A. C. (2002) Regulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma-mediated gene expression. A new mechanism of action for high density lipoprotein. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 23582–23586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hsi L. C., Wilson L., Nixon J., Eling T. E. (2001) 15-Lipoxygenase-1 metabolites down-regulate peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ via the MAPK signaling pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 34545–34552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Reginato M. J., Krakow S. L., Bailey S. T., Lazar M. A. (1998) Prostaglandins promote and block adipogenesis through opposing effects on peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 1855–1858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Adams M., Reginato M. J., Shao D., Lazar M. A., Chatterjee V. K. (1997) Transcriptional activation by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ is inhibited by phosphorylation at a consensus mitogen-activated protein kinase site. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 5128–5132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shao D., Rangwala S. M., Bailey S. T., Krakow S. L., Reginato M. J., Lazar M. A. (1998) Interdomain communication regulating ligand binding by PPAR-γ. Nature 396, 377–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jeong H. J., Lee H. S., Kim K. S., Kim Y. K., Yoon D., Park S. W. (2008) Sterol-dependent regulation of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 expression by sterol-regulatory element binding protein-2. J. Lipid Res. 49, 399–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dubuc G., Chamberland A., Wassef H., Davignon J., Seidah N. G., Bernier L., Prat A. (2004) Statins upregulate PCSK9, the gene encoding the proprotein convertase neural apoptosis-regulated convertase-1 implicated in familial hypercholesterolemia. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 24, 1454–1459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Careskey H. E., Davis R. A., Alborn W. E., Troutt J. S., Cao G., Konrad R. J. (2008) Atorvastatin increases human serum levels of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9. J. Lipid Res. 49, 394–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Welder G., Zineh I., Pacanowski M. A., Troutt J. S., Cao G., Konrad R. J. (2010) High-dose atorvastatin causes a rapid sustained increase in human serum PCSK9 and disrupts its correlation with LDL cholesterol. J. Lipid Res. 51, 2714–2721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dong B., Wu M., Li H., Kraemer F. B., Adeli K., Seidah N. G., Park S. W., Liu J. (2010) Strong induction of PCSK9 gene expression through HNF1α and SREBP2. Mechanism for the resistance to LDL-cholesterol lowering effect of statins in dyslipidemic hamsters. J. Lipid Res. 51, 1486–1495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Konrad R. J., Troutt J. S., Cao G. (2011) Effects of currently prescribed LDL-C-lowering drugs on PCSK9 and implications for the next generation of LDL-C-lowering agents. Lipids Health Dis. 10, 38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Benjannet S., Rhainds D., Hamelin J., Nassoury N., Seidah N. G. (2006) The proprotein convertase (PC) PCSK9 is inactivated by furin and/or PC5/6A. Functional consequences of natural mutations and post-translational modifications. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 30561–30572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kourimate S., Le May C., Langhi C., Jarnoux A. L., Ouguerram K., Zaïr Y., Nguyen P., Krempf M., Cariou B., Costet P. (2008) Dual mechanisms for the fibrate-mediated repression of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 9666–9773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chan D. C., Hamilton S. J., Rye K. A., Chew G. T., Jenkins A. J., Lambert G., Watts G. F. (2010) Fenofibrate concomitantly decreases serum proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 and very-low-density lipoprotein particle concentrations in statin-treated type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 12, 752–756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cameron J., Ranheim T., Kulseth M. A., Leren T. P., Berge K. E. (2008) Berberine decreases PCSK9 expression in HepG2 cells. Atherosclerosis 201, 266–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Li H., Dong B., Park S. W., Lee H. S., Chen W., Liu J. (2009) Hepatocyte nuclear factor 1α plays a critical role in PCSK9 gene transcription and regulation by the natural hypocholesterolemic compound berberine. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 28885–28895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Noguchi T., Kobayashi J., Yagi K., Nohara A., Yamaaki N., Sugihara M., Ito N., Oka R., Kawashiri M. A., Tada H., Takata M., Inazu A., Yamagishi M., Mabuchi H. (2011) Comparison of effects of bezafibrate and fenofibrate on circulating proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 and adipocytokine levels in dyslipidemic subjects with impaired glucose tolerance or type 2 diabetes mellitus. Results from a crossover study. Atherosclerosis 217, 165–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Troutt J. S., Alborn W. E., Cao G., Konrad R. J. (2010) Fenofibrate treatment increases human serum proprotein convertase subtilisin kexin type 9 levels. J. Lipid Res. 51, 345–351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Costet P., Hoffmann M. M., Cariou B., Guyomarc'h D. B., Konrad T., Winkler K. (2010) Plasma PCSK9 is increased by fenofibrate and atorvastatin in a non-additive fashion in diabetic patients. Atherosclerosis 212, 246–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]