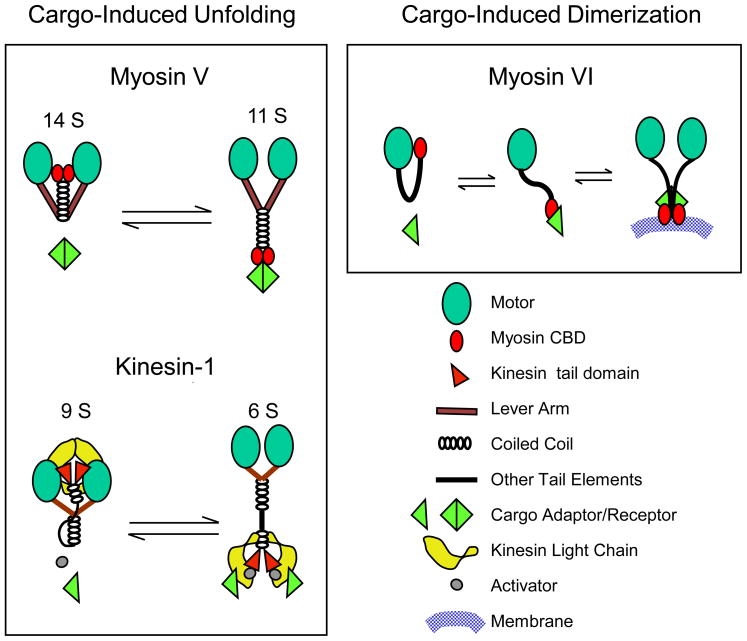

Figure 2. Cargo-dependent regulation of motors.

The schemes illustrate the two main mechanisms identified to date where cargo can regulate motor mechanochemistry: cargo-driven unfolding (myosin V and kinesin-1) and cargo-driven dimerization (myosin VI). In the case of myosin V [41] and kinesin-1 [40], these intrinsically dimeric molecules exist in a folded, enzymatically and mechanically quiescent state in the absence of cargo, and in an extended, active state in the presence of cargo. In the case of myosin V, one such unfolding/activating cargo is melanophilin [77], while the unfolding/activation of kinesin-I requires an activator (FEZ1) in addition to a cargo (JIP1) [40]. Whether cargos simply trap the motor kinetically in its extended state or can allosterically induce the extended state remains an important unanswered question. Interestingly, fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) studies showed that in folded kinesin-I, the motor’s light chains push the heads far apart, presumably to inhibit motility [40]. Other kinesin family members (e.g. kinesin-2, kinesin-7) are also subject to cargo-dependent unfolding/activation [40]. In the case of myosin VI, a quiescent, folded monomer can be converted to an extended processive dimer through interaction with dimeric cargo [9 ″″]. Dimerization may be facilitated by subsequent self association of the myosin VI heavy chains through weak coiled coil interactions, as well as by the sensing of membrane lipids by the CBD. Note that the properties of the medial tail of myosin VI (e.g. contribution to dimerization, lever arm length, reverse movement, etc) are currently areas of intense debate (see [43] for review). The cargo-unfolded, monomeric, non-processive version of myosin VI might also support certain cellular functions.