Abstract

One recent, double-blind, randomized clinical trial with 200 patients showed that clarithromycin administered intravenously for 3 days in patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) accelerated the resolution of pneumonia and decreased the risk of death from septic shock and multiple organ dysfunctions (MODS). The present study focused on the effect of clarithromycin on markers of inflammation in these patients. Blood was drawn immediately before the administration of the allocated treatment and on six consecutive days after the start of treatment. The concentrations of circulating markers were measured. Monocytes and neutrophils were isolated for immunophenotyping analysis and for cytokine stimulation. The ratio of serum interleukin-10 (IL-10) to serum tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) was decreased in the clarithromycin group compared with the results in the placebo group. Apoptosis of monocytes was significantly increased on day 4 in the clarithromycin group compared with the rate of apoptosis in the placebo group. On the same day, the expression of CD86 was increased and the ratio of soluble CD40 ligand (sCD40L) to CD86 in serum was unchanged. The release of TNF-α, IL-6, and soluble triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1 (sTREM-1) by circulating monocytes after stimulation was greater in the clarithromycin group than in the placebo group. The expression of TREM-1 on monocytes was also increased in the former group. These effects were pronounced in patients with septic shock and MODS. These results suggest that the administration of clarithromycin restored the balance between proinflammatory versus anti-inflammatory mediators in patients with sepsis; this was accompanied by more efficient antigen presentation and increased apoptosis. These effects render new perspectives for the immunotherapy of sepsis.

INTRODUCTION

Severe sepsis and septic shock are among the leading causes of death worldwide. It is estimated that more than 3 million people annually develop severe sepsis and septic shock in North America and Northern Europe; 35% to 50% of them die (9). In a recent survey in hospitals in Greece, mortality from septic shock was almost 65% for patients outside the intensive care unit (ICU) and almost 50% for patients hospitalized in an ICU (8).

The high lethality of sepsis syndrome has led to an early understanding that factors other than direct growth of the invading microorganism have an impact on the final outcome and that one of these factors is the overwhelming inflammatory reaction often seen in patients with sepsis (15). Several clinical trials have been performed with agents aiming to modulate the exaggerated inflammatory response of the host. However, most of these trials ended in failure (20), probably due to factors such as heterogeneity of the patient population and poor selection of study cohorts. In a multicenter, double-blind, randomized clinical trial conducted in Greece (4), a homogeneous cohort of 200 patients with sepsis due to ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) were allocated to receive intravenously either placebo or clarithromycin for three consecutive days. The two treatment groups did not differ in disease severity and in the appropriateness of coadministered antimicrobial agents. The results revealed significant clinical benefits of clarithromycin in the following parameters: (i) resolution of VAP, reduced from 15.5 days to 10.0 days; (ii) time to deintubation, reduced from 22.5 days to 16.0 days; and (iii) mortality, with an odds ratio (OR) for death due to septic shock and multiple-organ dysfunction (MODS) of 19.00 in the placebo group which was reduced to 3.78 in the clarithromycin group.

This profound clinical benefit created the need to better understand the mechanism of intervention of clarithromycin in the pathophysiology of sepsis. The present study was performed with biological materials collected from the patients participating in the trial. To obtain insight into the probable mechanisms behind the beneficial effects of clarithromycin, we tested a broad panel of biomarkers. Furthermore, particular emphasis was given to the probable effect of clarithromycin on the innate immune response as assessed by the function of circulating monocytes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design.

A total of 200 patients were enrolled in this multicenter, double-blind, randomized trial after written informed consent was obtained from their first-degree relatives, as previously described (4) (www.clinicaltrials.gov, NCT00297674). All patients were suffering from septic syndrome and VAP, and they were randomly allocated to receive blindly either intravenous placebo or clarithromycin treatment for three consecutive days through a central catheter. The administered regimen of clarithromycin was 1 g within 1 h of continuous infusion through a central catheter. Twenty milliliters of peripheral blood was collected from each patient before the start of blinded treatment (day 0) and on six consecutive days after the start of blinded treatment by venipuncture of one forearm vein under sterile conditions. Five milliliters of blood was collected into one pyrogen-free tube (Vacutainer; Becton Dickinson, Cockeysville, MD), and the remainder was collected into two heparin-coated tubes (Vacutainer). Blood was transported within 2 h to the laboratory for processing on the same day. More precisely, the workload on the day of sampling involved (i) tube centrifugation and storage of serum at −70°C, (ii) isolation of monocytes and neutrophils, (iii) flow cytometry on freshly isolated monocytes and neutrophils, and (iv) functional analysis of freshly isolated monocytes and neutrophils. This was done by stimulation of monocytes and neutrophils. The supernatants after stimulation were stored at −70°C. As such, no cell populations were kept frozen, whereas the stimulation of monocytes and neutrophils was real time. Freezing and rethawing of serum and of cell supernatants results in a variation of cytokine measurements by less than 3% compared with the value measured before freezing.

Serum markers.

The concentrations of C-reactive protein (CRP) were estimated in serum by nephelometry (Behring, Berlin, Germany). The lower limit of detection was 3.2 mg/liter. The concentrations of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (ΤΝF-α), of interleukin-10 (IL-10), and of soluble CD40 ligand (sCD40L) were measured in serum by an enzyme immunoassay (R&D, Inc., Minneapolis, MN). The lowest limits of detection were 20 pg/ml for TNF-α, 12.5 pg/ml for IL-10, and 10 pg/ml for sCD40L. The ratio of serum IL-10 to serum TNF-α was measured for each day of sampling. This ratio was used as an index of the anti-inflammatory to proinflammatory capacity of serum, as proposed elsewhere (7).

Cytokine stimulation assays and flow cytometry.

The collected heparinized venous blood was layered over Ficoll-Hypaque (Biochrom, Berlin, Germany) and centrifuged. Isolated mononuclear cells were washed three time with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.2) (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and incubated with RPMI 1640 enriched with 10% fetal bovine serum and 2 mM glutamine in the presence of 100 U/ml penicillin G and 0.1 mg/ml streptomycin (Sigma Co., St. Louis, MO) in 25-cm3 flasks. After 1 h of incubation at 37°C in 5% CO2, nonadherent cells were removed; adherent monocytes were thoroughly washed with Hanks' solution (Biochrom). Monocytes were then harvested with a 0.25% trypsin–0.02% EDTA solution (Biochrom) and counted in a Neubauer plate with trypan blue exclusion of dead cells. Their purity was more than 95% as determined after staining with anti-CD14-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (emission, 525 nm; Immunotech, Marseille, France) and reading through the EPICS XL/MSL flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter Co., Miami, FL). Unstained cells served as negative controls.

To define the functional status of freshly isolated monocytes, monocytes were distributed in 2 wells of a 12-well plate; they were incubated with RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 2 mM glutamine for 24 h at 37°C in 5% CO2 in the absence/presence of 10 ng/ml purified lipopolysaccharide (LPS) derived from Escherichia coli O55:H5 (Sigma Co.). After incubation, the plate was centrifuged and cell supernatants were collected and kept refrigerated at −70°C until assayed. The concentrations of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-10 in supernatants were estimated with an enzyme immunoassay (lowest detection limit, 20 pg/ml; R&D, Inc.). The concentrations of soluble triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1 (sTREM-1) were estimated in supernatants of monocytes isolated on days 0, 2, 4, and 6. The results were expressed as pg/104 live cells.

Apoptosis and expression of TREM-1 and CD86 were determined on cell membranes. Fresh monocytes isolated on days 0, 2, 4, and 6 without any previous stimulation with LPS were used. Cells were stained for 15 min in the dark with the protein annexin-V–FITC (emission, 525 nm; Immunotech), with anti-TREM-1–phycoerythrin (PE) (emission, 575 nm; R&D, Inc.), with anti-CD86–PE (emission, 575 nm; Immunotech), and with propidium iodide (PI) (emission 650 nm; Immunotech). Unstained cells served as negative controls. Apoptosis was expressed as the percentage of monocytes staining positive for annexin-V and staining negative for PI after running through the EPICS XL/MSL flow cytometer. The levels of expression of TREM-1 and CD86 were assessed both by percentage and by mean fluorescence intensity (MFI).

To define the functional status of freshly isolated neutrophils, neutrophils were isolated on days 0, 2, 4, and 6. The cell pellet remaining after centrifugation of heparinized blood over Ficoll was lysed with 1.0 mM ammonium chloride. Neutrophils were washed three times with ice-cold PBS (pH 7.2) and counted in a Neubauer plate with trypan blue exclusion of dead cells. Their purity was more than 99% as determined after staining with anti-CD15–FITC (emission 525 nm; Immunotech) and reading through the EPICS XL/MSL flow cytometer. Unstained cells served as negative controls. Neutrophils were distributed in 2 wells of a 12-well plate; they were incubated with RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 2 mM glutamine for 24 h at 37°C in 5% CO2 in the absence/presence of 10 ng/ml LPS. After incubation, the plate was centrifuged and cell supernatants were collected and kept refrigerated at −70°C until being assayed for sTREM-1. The results were expressed as pg/105 live cells. Fresh neutrophils isolated on days 0, 2, 4, and 6 without any previous stimulation with LPS were also used for analysis of the expression of TREM-1 on cell membranes by flow cytometry with the method described above for the expression of TREM-1 on cell membranes of monocytes.

Blinded procedure.

Investigators involved in blood processing were completely blind to the allocated treatment. Data for each patient were entered in a case report form; all forms were thoroughly checked by a monitor blinded to the allocated treatment.

Statistical analysis.

The measured parameters under consideration did not follow the normal distribution. Therefore, all the dependent variables were log transformed and the results were expressed as the means ± standard deviations. The resulting normally distributed variables were subsequently subjected to the two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) procedure with the treatment (placebo/clarithromycin) and the presence of MODS and septic shock (no/yes) as the between-subjects factors. This was done because a significant benefit in mortality was found in that subgroup of patients (4). Apart from the main effects, the two-way interaction effect (treatment group by presence of septic shock and MODS) was considered. This was followed by post hoc pairwise comparisons between the two treatment groups within each risk group and between the two risk groups within each treatment group with the necessary Bonferroni corrections. Therefore, there were four pairs that were tested for significant differences: (i) pairwise comparisons of placebo versus clarithromycin treatment groups within the absence of septic shock and MODS group, (ii) pairwise comparisons of placebo versus clarithromycin treatment groups within the presence of septic shock and MODS group, (iii) pairwise comparisons of the absence versus presence of septic shock and MODS group within the placebo group, and (iv) pairwise comparisons of the absence versus presence of septic shock and MODS groups within the clarithromycin group. Any P value below 0.05 after adjustment for multiple comparisons was considered statistically significant. Comparisons between groups on day 4 of sampling were considered of primary significance because day 4 was early after the end of the administration of the allocated treatment. As a consequence, it was expected that the maximal effect of changes induced by clarithromycin would be found at that specific time point.

In order to investigate the possibility of an interaction between intravenous administration of hydrocortisone and blind treatment in any of the measured parameters, all dependent variables were also subjected to three-way ANOVA with the treatment (placebo/clarithromycin), the presence of MODS and septic shock (no/yes), and hydrocortisone administration (no/yes) as the between-subjects factors, including all the two- and three-way interaction effects. This was followed by all eight possible post hoc pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni corrections, reporting all cases where differences were statistically significant.

RESULTS

Study population.

One hundred patients were allocated to treatment with placebo, and another 100 patients were allocated to treatment with clarithromycin. Thirty-six of the patients allocated to placebo and 33 of the patients allocated to clarithromycin, i.e., 69 in total, presented with septic shock and MODS. The two treatment groups did not differ in their clinical characteristics, namely, gender, age, underlying diseases, disease severity, implicated pathogens, and appropriateness of administered antimicrobials, as presented in detail elsewhere (4).

Serum markers.

The baseline values of the IL-10/TNF-α ratio on day 0 before allocation to blinded treatment did not differ between groups. However, analysis revealed a significant decrease in the IL-10/TNF-α ratio on day 4 among clarithromycin-treated patients compared to the ratio in placebo-treated patients for patients with septic shock and MODS (Fig. 1). It should be emphasized that on day 4, this ratio was far greater among patients with septic shock and MODS than among patients without septic shock and MODS within the placebo group; the clarithromycin treatment led to a significant drop in the serum IL-10/TNF-α ratio of the high-risk group (presence of septic shock and MODS), to the same levels as in the low-risk group (absence of septic shock and MODS).

Fig 1.

Ratios of serum interleukin-10 (IL-10) to serum tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) on day 4 after allocation to treatment. P values refer to indicated comparisons between placebo and clarithromycin. The asterisk denotes a significant difference for the comparison between placebo-treated patients without septic shock and MODS and placebo-treated patients with septic shock and MODS (P = 0.007). A similar difference was not found within the clarithromycin group. IL-10/TNF-α ratios of day 0 are also shown.

No differences in serum CRP concentrations were found for all days of sampling (concentrations are not shown and Table 1).

Table 1.

P values of the comparisons between placebo-treated patients and clarithromycin-treated patients for all days for the parameters under investigationa

| Parameter |

P value for day: |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| Patients without septic shock and MODS | |||||||

| Serum IL-10/TNF-α ratio | 0.460 | 0.926 | 0.845 | 0.571 | 0.235 | 0.326 | 0.818 |

| Serum CRP | 0.202 | 0.359 | 0.732 | 0.751 | 0.067 | 0.702 | 0.549 |

| Monocyte apoptosis (%) | 0.450 | 0.624 | 0.852 | 0.794 | |||

| CD86 (%) on monocytes | 0.183 | 0.035 | 0.146 | 0.774 | |||

| CD86 (MFI) on monocytes | 0.508 | 0.561 | 0.742 | 0.314 | |||

| Serum sCD40L | 0.275 | 0.308 | 0.153 | 0.853 | 0.387 | 0.362 | 0.980 |

| TREM-1 (%) on monocytes | 0.116 | 0.295 | 0.468 | 0.032 | |||

| TNF-α release by LPS-stimulated monocytes | 0.052 | 0.613 | 0.013 | 0.267 | 0.023 | 0.498 | 0.008 |

| IL-6 release by LPS-stimulated monocytes | 0.265 | 0.259 | 0.171 | 0.354 | 0.194 | 0.435 | 0.292 |

| sTREM-1 release by LPS-stimulated monocytes | 0.904 | 0.059 | 0.100 | 0.677 | |||

| TREM-1 (%) on neutrophils | 0.782 | 0.745 | 0.211 | 0.888 | |||

| sTREM-1 release by LPS-stimulated neutrophils | 0.542 | 0.251 | 0.222 | 0.646 | |||

| Patients with septic shock and MODS | |||||||

| Serum IL-10/TNF-α ratio | 0.146 | 0.822 | 0.104 | 0.422 | 0.040 | 0.626 | 0.610 |

| Serum CRP | 0.761 | 0.116 | 0.223 | 0.503 | 0.810 | 0.468 | 0.540 |

| Monocyte apoptosis (%) | 0.435 | 0.563 | 0.006 | 0.618 | |||

| CD86 (%) on monocytes | 0.629 | 0.672 | 0.024 | 0.175 | |||

| CD86 (MFI) on monocytes | 0.157 | 0.316 | 0.011 | 0.881 | |||

| Serum sCD40L | 0.998 | 0.861 | 0.795 | 0.792 | 0.667 | 0.382 | 0.322 |

| TREM-1 (%) on monocytes | 0.843 | 0.025 | 0.280 | 0.330 | |||

| TNF-α release by LPS-stimulated monocytes | 0.463 | 0.572 | 0.713 | 0.413 | 0.007 | 0.336 | 0.204 |

| IL-6 release by LPS-stimulated monocytes | 0.531 | 0.886 | 0.840 | 0.532 | 0.034 | 0.463 | 0.025 |

| sTREM-1 release by LPS-stimulated monocytes | 0.505 | 0.305 | 0.089 | 0.416 | |||

| TREM-1 (%) on neutrophils | 0.276 | 0.018 | 0.358 | 0.081 | |||

| sTREM-1 release by LPS-stimulated neutrophils | 0.109 | 0.105 | 0.117 | 0.477 | |||

The comparisons were evaluated independently for patients without septic shock and multiple organ dysfunctions (MODS) and for patients with septic shock and MODS. Significant values are given in boldface. Empty cells represent days when the indicated parameter was not measured according to study design.

Apoptosis of monocytes.

Apoptosis of monocytes on day 4 is shown in Fig. 2. The baseline values on day 0 did not differ between groups. Apoptosis of monocytes was significantly increased among clarithromycin-treated patients with septic shock and MODS compared with the level in placebo-treated patients (P = 0.006). No significant differences were found on the other days of sampling (percent values not shown and Table 1).

Fig 2.

Apoptosis of monocytes of placebo-treated patients and of clarithromycin-treated patients on day 4 after allocation to treatment. P values refer to indicated comparisons between placebo and clarithromycin groups. The respective values from day 0 are also shown.

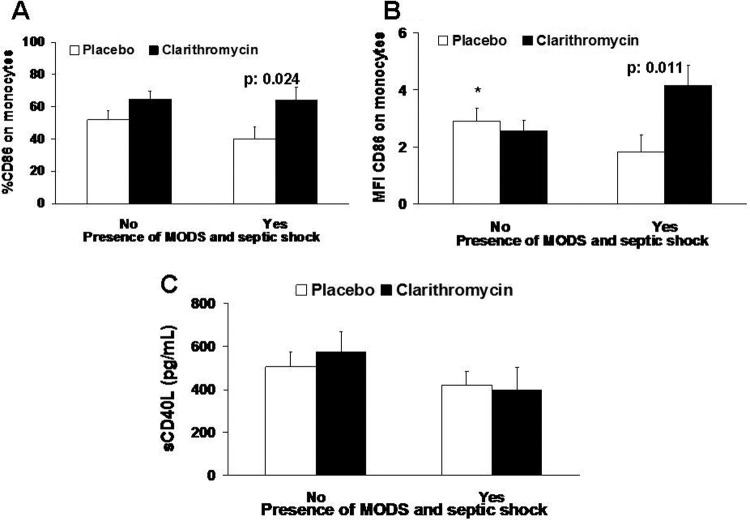

Biomarkers of antigen presentation.

The expression of CD86 on monocytes on day 4 is shown in Fig. 3. The baseline values on day 0 did not differ between groups (percent and MFI values are not shown and Table 1). The expression of CD86 on monocytes on day 4 was significantly increased among clarithromycin-treated patients with septic shock and MODS compared with the level in placebo-treated patients. This difference involved both the percentage of expression of the surface antigen CD86 on monocytes and the MFI. In the same time interval, the serum levels of sCD40L did not differ between groups. No differences were found on the other days of sampling (percent and MIF values and concentrations are not shown and Table 1).

Fig 3.

Biomarkers of antigen presentation of placebo-treated patients and of clarithromycin-treated patients on day 4 after allocation to treatment. Data on the surface antigen CD86 are given both as percentage of isolated monocytes (A) and as mean fluorescence intensity (B). Concentrations of soluble CD40 ligand (sCD40L) are shown (C). P values refer to indicated comparisons between placebo and clarithromycin. The asterisk denotes a significant difference for the comparison between placebo-treated patients without septic shock and MODS and placebo-treated patients with septic shock and MODS (P = 0.028).

Cytokine stimulation assays.

The concentrations of TNF-α and IL-6 in supernatants of LPS-stimulated monocytes on day 4 are shown in Fig. 4. The baseline values on day 0 did not differ between groups (concentrations not shown and Table 1). The release of both cytokines was below the limit of detection in the supernatants of unstimulated monocytes. The release of TNF-α was significantly greater among clarithromycin-treated patients than among placebo-treated patients without septic shock and MODS; however, within the subgroup of patients with septic shock and MODS, the release of TNF-α was significantly lower among clarithromycin-treated patients than among placebo-treated patients. On the contrary, the release of IL-6 was significantly greater among clarithromycin-treated patients with septic shock and MODS than among placebo-treated patients.

Fig 4.

Production of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (ΤΝF-α) and of interleukin-6 (IL-6) by LPS-stimulated monocytes of placebo-treated patients and clarithromycin-treated patients on day 4 after allocation to treatment. P values denote statistically significant differences between the two groups at the indicated time intervals. Asterisks denote significant differences for comparisons between placebo-treated patients without septic shock and MODS and placebo-treated patients with septic shock and MODS (*, P = 0.002; **, P = 0.015).

IL-10 remained below the limit of detection in supernatants of monocytes on all days.

TREM-1 and sTREM-1.

Treatment with clarithromycin had a significant effect on the expression of TREM-1 on cell membranes of isolated monocytes and neutrophils (percent values are not shown and Table 1). The concentrations of sTREM-1 in supernatants of unstimulated monocytes were below the limit of detection. When stimulated, the release of sTREM-1 at baseline before allocation to blinded treatment was similar between groups (concentrations are not shown and Table 1). On day 4, the release of sTREM-1 by monocytes after stimulation with LPS presented a trend of being greater among clarithromycin-treated patients than among placebo-treated patients on day 4 in patients without septic shock and MODS (Fig. 5). No statistically significant effect on the release of sTREM-1 by neutrophils after stimulation with LPS was found for treatment with clarithromycin (Fig. 6).

Fig 5.

Release of soluble triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1 (sTREM-1) from LPS-stimulated monocytes of placebo-treated patients and clarithromycin-treated patients on day 4 after allocation to treatment. P values denote statistically significant differences between the two groups.

Fig 6.

Release of soluble triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1 (sTREM-1) from LPS-stimulated neutrophils of placebo-treated patients and clarithromycin-treated patients on day 4 after allocation to treatment.

An overview of the P values of statistical comparisons between both groups for all days of the investigation is given in Table 1.

The effect of hydrocortisone.

Twenty-five patients allocated to the placebo group and 22 patients allocated to the clarithromycin group were undergoing replacement therapy with low intravenous doses of hydrocortisone to compensate for stress (4). Since hydrocortisone is an anti-inflammatory agent, the possibility of an interaction with clarithromycin in any of the measured parameters was investigated. No significant interaction between the coadministration of clarithromycin and hydrocortisone was found for any of the measured parameters either in patients without septic shock and MODS or in patients with septic shock and MODS.

DISCUSSION

A double-blind, randomized clinical trial by our group involving patients with VAP and sepsis showed significant benefits from the intravenous administration of clarithromycin (4); the times to resolution of VAP and weaning from mechanical ventilation were shortened, and the relative risk for death from septic shock and MODS was decreased. Assays of serum biomarkers and cytokine stimulations were performed daily over the follow-up of these patients, and the results are presented here. The analysis performed was done separately for patients with septic shock and MODS because they were the subgroup where most of the benefit in survival from the administration of clarithromycin was found.

The analysis presented provides robust evidence that the administration of clarithromycin was accompanied by significant effects on all studied aspects of the biology of circulating monocytes. This effect was seen on day 4, i.e., 2 days after the end of the administration of the allocated treatment. This tight time connection between treatment and effect may indicate that clarithromycin is a modulator of the biological function of monocytes. This modulation was pronounced in patients with septic shock and MODS, although significant effects were found, albeit to a lesser extent, in patients without septic shock and MODS. Septic shock and MODS were the main drivers for death in this study (4). These patients were almost 35% of the total enrolled patients, and their number was adequate to draw safe statistical conclusions. The data provided on the cell populations studied, i.e., monocytes and neutrophils, are robust and support the action of clarithromycin because they involve real-time analysis performed on viable cells isolated on the day of sampling. A similar study design has never before been conducted and published in the literature. The parameters measured were both descriptive and functional. The descriptive variables were the increases in the expression of CD86 and TREM-1 on cell membranes of monocytes and the increase in the rate of apoptosis of monocytes. The functional assays were the real-time stimulation of circulating monocytes with LPS for the release of TNF-α, IL-6, and sTREM-1. The changes in these parameters were pronounced in the subgroup of patients with septic shock and MODS. These changes should be discussed in light of the decrease of the ratio of serum IL-10 to TNF-α to create a hypothesis about the probable mechanism of action of clarithromycin.

It is now widely recognized that when severe sepsis and MODS develop, the host has entered into a state of immunoparalysis (15). The key components of sepsis-induced immunoparalysis are (i) failure of monocytes in adequate cytokine production after stimulation, (ii) failure of antigen presentation, and (iii) predominance of anti-inflammatory cytokines over proinflammatory cytokines in serum (5, 14). The increase of the ratio of IL-10 over TNF-α is the main expression of that alteration (7).

It is hypothesized that the failure of most randomized clinical studies to improve the outcome of sepsis patients is due to lack of effect on sepsis-induced immunoparalysis. Although the available data do not provide any evidence about the intracellular mechanism of action of clarithromycin, reversal of immunoparalysis seems to be a component of the benefit seen in patients in the present study. All key components of immunoparalysis were affected, i.e., the IL-10/TNF-α ratio of serum was decreased, production of cytokines by circulating monocytes upon stimulation with LPS was increased, and markers of antigen presentation were improved. All these effects were achieved on day 4 early upon the end of treatment. Although most of the data presented here point toward reversal of immunoparalysis as part of the explanation for the effect of clarithromycin, there is evidence that clarithromycin inhibited the proinflammatory response. More precisely, among patients with septic shock and MODS, clarithromycin treatment decreased the release of TNF-α.

TREM-1 is a receptor engaged on cell membranes of monocytes and neutrophils. Stimulation of that receptor leads to the production of proinflammatory cytokines, mainly TNF-α and IL-8 (18); in parallel, the receptor is shed through cleavage from the cell membrane in a soluble form known as sTREM-1 (6). A recent publication of the Hellenic Sepsis Study Group showed that, when sepsis develops in the context of VAP, the expression of TREM-1 on circulating monocytes and on circulating neutrophils is decreased upon the transition from sepsis to severe sepsis/shock and this is a component of sepsis-induced immunoparalysis (13). The increase of the expression of TREM-1 on the cell membrane of monocytes, along with the increased production of sTREM-1 by monocytes, is another finding indicating the reversal of immunoparalysis of circulating monocytes achieved by the clarithromycin treatment.

Clarithromycin treatment was also accompanied by two additional effects on monocytes: induction of apoptosis and stimulation of the expression of the costimulatory molecule CD86. The effects of clarithromycin on apoptosis of monocytes were pronounced among patients with septic shock and MODS. It is not known whether the mean increase of apoptosis of circulating monocytes by 12% in the clarithromycin arm can explain the efficacy of clarithromycin in the overall prolongation of survival of these patients. No similar animal model has ever been described. However, a clinical investigation by our group of 36 patients with septic shock developing in the context of VAP described a considerable prolongation of survival when apoptosis of circulating monocytes was increased (3).

The proapoptotic effect on monocytes described may be either direct or indirect. A direct effect would signify that clarithromycin may act on monocytes and induce apoptosis. An indirect effect would signify that the complex modulation of the inflammatory cascade by clarithromycin may affect the apoptosis of monocytes.

CD86 is a costimulatory molecule involved in antigen presentation. It is expressed on dendritic cells, on peritoneal cells, on monocytes, and on macrophages (1, 10). The expression of CD86 on monocytes is defective during the sepsis process, as demonstrated in both animal studies and human studies (11). The failure of human monocytes to express CD86 early in sepsis is associated with poor outcome (12). Thus, the increased expression of CD86 on monocytes may contribute to the benefit of clarithromycin treatment. CD40L is expressed on activated CD4 lymphocytes and binds CD40 of monocytes during antigen presentation. Circulatory concentrations of sCD40L are considered a reflection of the expression of CD40L (17). As a consequence, since the levels of sCD40L did not change upon treatment with clarithromycin, whereas the expression of CD86 on monocytes was increased in parallel, it may be postulated that therapy with clarithromycin was accompanied by more efficient antigen presentation.

It should be underscored that no interaction of clarithromycin with coadministered hydrocortisone was found for any of the parameters studied.

Five main limitations of the present study should be addressed. (i) The coexpression of HLA-DR on CD14 monocytes, which is considered an index of immunoparalysis (16), was not measured. However, the sequential estimates of cytokine release by circulating monocytes counterbalance this lack, and they represent an approach never described before in clinical trials. (ii) Subpopulations of lymphocytes were not studied. However, daily measurements of the ratio of circulating IL-10/TNF-α are proposed to represent an indirect index of the existing balance between Th1 and Th2 cell responses (2). (iii) The intracellular concentrations of clarithromycin in isolated monocytes and neutrophils were not measured. Macrolides are known to accumulate intracellularly (19), and measurement of the intracellular concentrations of clarithromycin may help explain the results of the functional assays of freshly isolated monocytes and neutrophils. (iv) Similar parameters in the lung were not studied. Ideally, macrophages should have been isolated from the tracheobronchial secretions of patients and stimulated for cytokine production. In parallel, cytokine measurements should have been performed in tracheobronchial secretions of patients. These would allow comparison of the effect of treatment with clarithromycin in the peripheral circulation with the effect in the lung. These measurements were not part of the initial study design (www.clinicaltrials.gov, NCT00297674), and they were not conducted. (v) Similar measurements were not obtained at later time intervals. Clinical data suggest that benefit from treatment with clarithromycin was shown between days 12 and 20 (4). At these time intervals, serum and cellular factors were not studied. This was because the greatest modulation of the function of monocytes was expected by the end of treatment, i.e., on day 4, according to the original study design. Although the findings presented agree with this expectation, they cannot exclude the existence of some important potential findings at later time intervals.

The present study compared serum markers, immunophenotyping characteristics of monocytes and neutrophils, and the ex vivo function of monocytes and neutrophils in patients with VAP and sepsis who participated in a double-blind, randomized clinical trial and who were treated either with placebo or with clarithromycin (Fig. 7). The results pointed toward an effect on circulating monocytes. The results presented further underscore the promising perspective of immunotherapy of sepsis with intravenous administration of clarithromycin.

Fig 7.

Main effects of treatment with clarithromycin found in serum cytokines and in freshly isolated monocytes. Abbreviations: ShMODS, septic shock and multiple organ dysfunctions; mCD86, membrane CD86 measured by flow cytometry; mTREM-1, membrane TREM-1 measured by flow cytometry; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor alpha; IL, interleukin; ↓, decrease; ↑, increase; Rx, administration of blind treatment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None of the authors has any conflict of interest related to the manuscript.

The study was supported by an unrestricted educational grant by Abbott Laboratories (Hellas) S.A. M.G.N. was supported by a Vici grant from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 7 May 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Ding Y, et al. 2004. Polymicrobial sepsis induces divergent effects on splenic and peritoneal dendritic cell function in mice. Shock 22:137–144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ. 2010. What is the pathophysiology of the septic host upon admission? Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 36(Suppl 2):S2–S5 doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2010.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ, et al. 2006. Early apoptosis of blood monocytes in the septic host: is it a mechanism of protection in the event of septic shock? Crit. Care 10:R76 doi:10.1186/cc4921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ, et al. 2008. Effect of clarithromycin in patients with sepsis and ventilator-associated pneumonia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 46:1157–1164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ, et al. 2011. Inhibition of caspase-1 activation in Gram-negative sepsis and experimental endotoxemia. Crit. Care 15:R27 doi:10.1186/cc9974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gibot S, et al. 2004. A soluble form of the triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1 modulates the inflammatory response in murine sepsis. J. Exp. Med. 200:1419–1426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gogos CA, Drosou E, Bassaris HP, Skoutelis A. 2000. Pro- versus anti-inflammatory cytokine profile in patients with severe sepsis: a marker for prognosis and future therapeutic options. J. Infect. Dis. 181:176–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hellenic Sepsis Study Group 2010. Presentation May 7, 2010. Hellenic Sepsis Study Group, Greece: www.sepsis.gr [Google Scholar]

- 9. Heron M. 2007. Deaths: leading causes for 2004. Natl. Vital Stat. Rep. 56:1–95 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lanier LL, et al. 1995. CD80 (B7-1) and CD86 (B7-2) provide similar co-stimulatory signals for T cell proliferation, cytokine production, and generation of CTL. J. Immunol. 154:97–105 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Newton S, et al. 2004. Sepsis-induced changes in macrophage co-stimulatory molecule expression: CD86 as a regulator of anti-inflammatory IL-10 response. Surg. Infect. (Larchmt.) 5:375–383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nolan A, et al. 2009. 2009. Differential role for CD80 and CD86 in the regulation of the innate immune response in murine polymicrobial sepsis. PLoS One 4:e6600 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0006600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Poukoulidou T, et al. 2011. TREM-1 expression on neutrophils and monocytes of septic patients: relation to the underlying infection and the implicated pathogen. BMC Infect. Dis. 11:309 doi:10.1186/1471-2334-11-309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Remick DG. 2007. Pathophysiology of sepsis. Am. J. Pathol. 170:1435–1444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rittisch D, Flierl MA, Ward PA. 2008. Harmful molecular mechanisms in sepsis. Nat. Immunol. 8:776–786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sáenz JJ, Izura JJ, Manrique A, Sala F, Gaminde I. 2001. Early prognosis in severe sepsis via analyzing the monocyte immunophenotype. Intensive Care Med. 27:970–977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sinistro A, et al. 2008. Downregulation of CD40 ligand response in monocytes from sepsis patients. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 15:1851–1858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tesarz AS, Cerwenka A. 2008. The TREM-1/DAP12 pathway. Immunol. Let. 116:111–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Togami K, Chono S, Morimoto K. 2011. Distribution characteristics of clarithromycin and azithromycin, macrolide antimicrobial agents used for the treatment of respiratory infections, in lung epithelial lining fluid and alveolar macrophages. Biopharm. Drug Dispos. 32:389–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Vincent JL, Sun Q, Dubois MJ. 2002. Clinical trials of immunomodulatory therapies in severe sepsis and septic shock. Clin. Infect. Dis. 34:1084–1093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]