Abstract

Background

This study examines the effects of types of liver resection on the growth of liver and lung metastasis.

Materials and Methods

Experimental liver metastases were established by spleen injection of the Colon 26 murine adenocarcinoma cell line expressing GFP into transgenic nude mice expressing RFP. Experimental lung metastases were established by tail vein injection with Colon 26-GFP. Three days after cell injection, groups of mice underwent liver resection (35%+35% [repeated minor resection] vs. 70% [major resection]). Metastatic tumor growth was measured by color-coded fluorescence imaging of the GFP-expressing cancer cells and RFP-expressing stroma.

Results

Although major and repeated minor resection removed the same volume of liver parenchyma, the two procedures had very different effects on metastatic tumor growth: major resection, stimulated liver and lung metastatic growth as well as recruitment of host-derived stroma compared to repeated minor resection. Repeated minor resection did not stimulate metastasis or stromal recruitment. There was no significant difference in liver regeneration between the two groups. Host-derived stroma density, which is stimulated by major resection compared to repeated minor resection, may stimulate growth in the liver-metastatic tumor. TGF-β is also preferentially stimulated by major resection and may play a role in stroma and metastasis stimulation.

Conclusions

The results of this study indicate that when liver resection is necessary, repeated minor liver resection is superior to major liver resection, since major resection, in contrast to repeated minor resection, stimulates metastasis, which should be taken into consideration in clinical situations indicating liver resection.

Keywords: Nude mice, liver resection, lung metastasis, liver metastasis, stroma, green fluorescent protein, red fluorescent protein, color-coded imaging

INTRODUCTION

Liver resection is often performed on patients with liver metastases [1-4]. However, the recurrence rate following liver resection of metastasis is high [5, 6]. Recurrence has been found in the remnant liver as well as at distant metastatic sites. Recurrence has been linked to several factors, including the accuracy of diagnosis and surgical technique. One hypothesis is that the type of liver resection may stimulate occult tumor growth at both intra-hepatic and extra-hepatic sites.

The degree of hepatic resection has been found to be a key factor in tumor stimulation. A number of studies have found that the larger the percentage of liver resection, the higher the incidence and volume of recurrence [7, 8]. Many factors upregulated during liver regeneration after liver resection have been implicated in tumor growth and recurrence [9-11] and the extent of the up-regulation of these factors correlated with the degree of liver resection. Numerous studies have suggested that regenerative growth factors, many of which are elevated immediately after liver resection, play a role in tumor recurrence by stimulating tumor cells to proliferate following resection [9]. However, the difference between a major liver resection and repeated minor resections, which remove the same volume of liver parenchyma in different ways, on the growth of malignant tumors is poorly understood.

Our laboratory pioneered in vivo imaging with green fluorescent protein (GFP) and/or red fluorescent protein (RFP) [12-14]. The use of fluorescent proteins for imaging in vivo has been particularly useful to study tumor growth and progression [12-14]. With the use of multiple colored-proteins, we developed color-coded imaging of the tumor-host interaction by color-coding cancer and stromal cells [15-19].

This study examines the effects of different types liver resection on the growth of the liver and the lung metastatic tumors in an experimental-metastasis mouse model using GFP-expressing cancer cells and RFP-expressing transgenic host nude mice producing RFP-expressing stroma, after major (70%) and repeated minor (35%+35%) liver resections.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

GFP gene transduction of cancer cells

For GFP gene transduction, 70% confluent Colon 26 murine adenocarcinoma cells were incubated with a 1:1 precipitated mixture of retroviral supernatants of PT67 GFP-expressing packaging cells and RPMI 1640 containing 10% fetal bovine serum for 72 h. Fresh medium was replenished at this time. Cells were harvested with trypsin/EDTA 72 h after transduction and subcultured at a ratio 1:15 into selective medium, which contained 200 mg/ml G418. The level of G418 was increased stepwise up to 800 mg/ml [19-21]. Clones of Colon 26 expressing high level of GFP (Colon26-GFP) were isolated with cloning cylinders using trypsin/EDTA and amplified by conventional culture methods.

Cell culture

Colon 26-GFP cells were maintained in RPMI1640 medium (Hyclone Laboratories, Logan, UT, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FCS; Hyclone Laboratories). The cells were incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air. The cells were collected after trypsinization and stained with trypan blue (Sigma). Only viable cells were counted with a hemocytometer (Hausser Scientific, Horsham, PA).

Animals

Mice were bred and maintained in a barrier facility under HEPA filtration at AntiCancer, Inc. Mice were fed with autoclaved laboratory rodent diet (Teckland LM-485; Western Research Products, Orange, CA). All animal studies were conducted in accordance with the principals and procedures outlined in the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals under PHS Assurance Number A3873-1.

Transgenic red fluorescent protein nude mice

C57/B6-RFP mice express the RFP (DsREDT3) under the control of a chicken β-actin promoter and cytomegalovirus enhancer. All of the tissues from this transgenic line, with the exception of erythrocytes, are red under blue excitation light [22].

Six-week-old transgenic RFP female mice were crossed with both 6-8-week-old BALB/c nu/nu and NCR nu/nu male mice (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN), respectively. Male F1 red fluorescent nude mice were crossed with female F1 immunocompetent RFP mice. When female F2 immunocompetent RFP mice were crossed with male RFP nude or F2 RFP nude male were backcrossed with female F1 immunocompetent RFP mice, approximately 50% of their offspring were RFP nude mice [15]. RFP nude mice were then consistently produced using the methods described above.

Surgical techniques

All surgical procedures were performed under general anesthesia using isoflurane (Isothesia, Butler Animal Health Supply, Dublin, OH) inhalation. The period of anesthesia was the same for all groups. Mouse liver resection was performed using the methods introduced by Higgins and Anderson [23]. We employed three models of liver resection: Minor liver resection (35%), consisting of the removal of the left lateral hepatic lobe, major liver resection (70%), consisting of the removal of the left lateral and median hepatic lobes, and repeated minor liver resection (35% +35%), in which seven days after left lateral hepatic lobe resection, the median hepatic lobe was resected. Midventral laparotomy was performed as a sham operation (0%). A hyaluronic acid-carboxymethylcellulose membrane (Seprafilm®, Kaken Pharmaceutical, Tokyo) was used in order to prevent liver adhesion to the abdominal wall after all types of liver resections and a sham operation.

Experimental liver metastasis

After anesthesia, an incision was made just below the rib cage on the left flank of the mouse and the spleen was exteriorized. To generate the experimental liver metastasis model, mouse Colon 26-GFP cells were injected at a concentration of 105 in 50 μL PBS into the spleen of RFP nude mice through a 31-gauge needle followed by subsequent splenectomy 3 min later. Three days after cancer cell injection, three types of liver resection were performed as well as the sham operation. Seventeen days after cancer cell injection (14 days after the first liver resection), mice were sacrificed and the liver was then removed. Liver regeneration was determined by weight. Tumor size was determined with the OV100 Small Animal Imaging System and the IV100 Intravital Scanning Laser Imaging System (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

Stroma recruitment in experimental liver metastasis

Host-derived RFP-expressing stroma was imaged in the GFP-expressing liver tumors. Tumor sections were imaged and analyzed for RFP intensity with the Olympus OV100. The mean host-derived stromal density in the liver tumors was calculated by total RFP intensity in the tumor cross-section divided by the tumor area (mm2).

Experimental lung metastasis

To generate the experimental lung metastasis model, a total of 200 μL PBS containing 2×105 Colon 26-GFP cells were injected into the tail vein of nude mice. Three days after cancer cell injection, the three types of liver resection as well as the sham operation were performed. Seventeen days after cancer cell injection (14 days after the first liver resection), mice were sacrificed and the lungs were removed. Liver weight and lung metastasis were examined. Lung metastases were examined using the OV100.

Blood sample collection and growth factor assay

Systemic venous blood samples were obtained from the inferior vena cava by direct puncture with a 27-gauge syringe in order to assess hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) at 3 days, 7 days, 10 days, and 14 days after liver resection. Minor liver resection, repeated minor liver resection, and major liver resection were compared. Five mice were used in each day and each group. Following collection of the samples into plasma separator tubes and centrifugation for 10 minutes at 3000 g, the plasma samples were stored at −80°C until analysis. The HGF, VEGF, and TGF-β concentrations were measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (HGF: Institute of Immunology, Japan, VEGF: IBL, Japan, and TGF-β: invitorgen, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Fluorescence imaging

The OV100 Small Animal Imaging System, containing an MT-20 light source (Olympus Biosystems, Planegg, Germany) and DP70 CCD camera (Olympus) [24] and the IV100 Intravital Scanning Laser Microscope [25] were used in this study. High-resolution images were captured directly on a personal computer (Fujitsu Siemens Computers, Munich, Germany). Images were analyzed with the use of CellR software (Olympus Biosystems).

Statistical Analysis

The experimental data are expressed as the mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was performed using the one-way ANOVA to evaluate any differences in the means among the 4 groups, and then pairwise comparisons was performed using the Tukey method test as a post hoc test. A p value less than 0.05 was used to indicate a significant difference.

RESULTS

Liver regeneration after liver resection

Fourteen days after liver resection, the liver was weighed in order to evaluate liver regeneration after liver resection. There was no significant difference in liver regeneration between the four types of resection (sham: 1.55 ± 0.33 g; minor liver resection: 1.44 ± 0.27 g; repeated minor liver resection: 1.43 ± 0.29 g; major liver resection: 1.44 ± 0.43 g, p = n.s.; Fig. 1). After repeated minor liver resection, the liver regenerated adequately within 7 days after the second liver resection. Ten mice were used in each group.

Fig. 1.

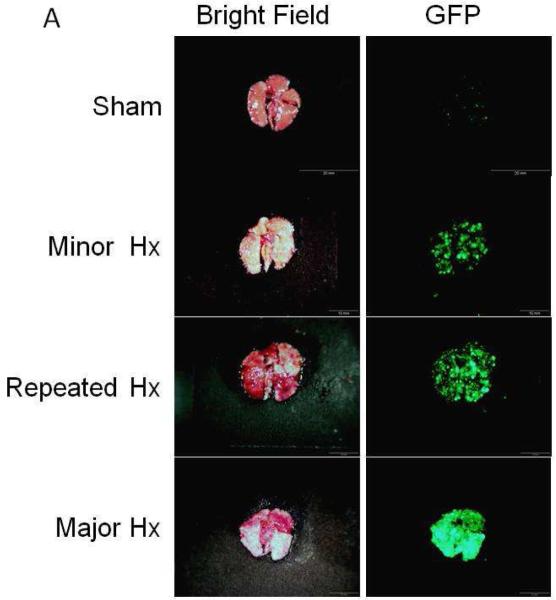

Lung metastasis after different types of liver resection. (A) macroscopic appearance of lungs. Experimental lung metastases were established by tail vein injection with a total of 200 μL PBS containing 2×105 Colon 26-GFP cells. Three days after cancer cell injection, four types of surgery were performed. Seventeen days after cancer cell injection (14 days after the first liver resection), mice were sacrificed and the lungs was excised. Excised lungs were imaged under bright light (left column) and fluorescence (right column). Fluorescence imaging visualized the Colon 26-GFP lung metastasis. Lung metastases were imaged and analyzed using the OV100 Small Animal Imaging System. (Scale Bars: 2 mm). (B) Quantitative analysis of the total GFP intensity in the lung after 4 types of resection. Major resection stimulated lung metastatic growth. In contrast to major resection, the other 3 types of resection including repeated minor resection, significantly had less growth of metastatic lung tumors (*: p < 0.001).

Lung metastasis after liver resection

Colon 26-GFP cells (2×105 cells / 200 μL PBS) were injected into the tail vein of nude mice to establish experimental lung metastasis. Three days after cancer cell injection, four types of surgery were performed. Seven mice were used in each group. Figure 1A shows the macroscopic appearance and GFP fluorescence of the Colon-26 cells on the lungs 14 days after the first liver resection (17 days after cancer cell injection). Major resection significantly stimulated lung metastatic growth. In contrast to major resection, the other 3 types of resection including repeated minor liver resection, had significantly fewer metastatic lung tumors (Fig. 1B, *: p < 0.001). There was no statistically-significant difference in lung metastasis between the sham, minor liver resection, or repeated minor liver resection (Sham vs minor liver resection: p = 0.865, minor liver resection vs repeated minor liver resection: p = 0.498, Sham vs repeated minor liver resection: p = 0.125; Fig. 1B).

Liver metastasis after liver resection

Colon 26-GFP cells (1×105 cells / 50 μL PBS) were injected into the spleen of RFP transgenic nude mice to establish experimental liver metastasis. Three days after cancer-cell injection, four types of surgery were performed. Seven mice were used in each group. Figure 2A shows fluorescence imaging of livers 14 days after the first liver resection (17 days after cancer cell injection). Color-coded fluorescence imaging visualized the RFP-expressing liver and the metastatic Colon-26-GFP cells. Major resection significantly stimulated liver metastatic growth. In contrast to major resection, the other 3 types of resection, including repeated minor resection, had significantly less liver metastasis (Fig. 2B, *: p < 0.001, **: p = 0.003). There were no statistically-significant differences among sham, minor liver resection, and repeated minor liver resection groups (sham vs minor liver resection: p = 0.983, minor liver resection vs repeated minor liver resection: p = 0.999, sham vs repeated minor liver resection: p = 0.993; Fig. 2B).

Fig.2.

Liver metastasis after different types of liver resection. (A) Macroscopic appearance of livers. Experimental liver metastases were established by intrasplenic injection of 50 μL PBS containing 1×105 Colon 26-GFP cells. Three days after cancer cell injection, four types of surgery were performed. Seventeen days after cancer cell injection (14 days after the first liver resection), mice were sacrificed and the liver was excised. Color-coded fluorescence imaging visualized the RFP expressing liver (left column) and Colon 26-GFP liver metastasis (middle column). Liver metastases were imaged and analyzed using the OV100 Small Animal Imaging System. (Scale Bars: 2 mm). (B) Quantitative analysis of the total GFP intensity in the liver of 4 types of resection. Major resection stimulated liver metastatic growth. In contrast to major resection, the other 3 types of resection including repeated minor resection, significantly had less effect on growth of metastatic liver tumors (*: p < 0.001, **:p = 0.003).

Effect of type of liver resection and recruitment of stroma in liver metastasis

Color-coded imaging of tumor–host interaction determined the density of RFP expressing host-derived stroma in GFP labeled liver metastatic tumors by measuring total RFP intensity (Fig. 3A). Seven mice were used in each group. The mean host-derived stroma density in the liver metastatic tumor after major liver resection was significantly greater than in the liver metastatic tumors after the other 3 types of resection, including repeated minor liver resection (Fig. 3B, p < 0.001). There were no statistically-significant differences among sham, minor liver resection, and repeated minor liver resection group (sham vs minor liver resection: p = 0.979, minor liver resection vs repeated minor liver resection: p = 0.988, sham vs repeated minor liver resection: p = 1.000; Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Color-coded imaging of stromal recruitment by liver-metastatic tumors after different types of liver resection. A: Host-derived RFP-expressing stroma was visualized in the liver metastasis of the GFP-expressing Colon 26 murine adenocarcinoma tumor in the transgenic RFP mouse. Images were taken with the Olympus OV100 Small Animal Imaging System (upper) and the Olympus IV100 intravital scanning microscope (lower) using tumor tissue obtained from the liver. (Scale bars; upper: 1mm, lower: 200 μm). (B) Quantitative analysis of the total RFP intensity in the GFP-expressing liver tumor of 4 types of resection. Total RFP intensity indicates the density of host-derived stroma in the liver metastatic tumor. The mean host-derived stroma density in the liver metastatic tumors after major liver resection was significantly more than in the liver metastatic tumors after other 3 types of resection including repeated minor resection (*: p < 0.001).

HGF, VEGF, and TGF-β level in plasma after liver resection

The time-course changes in HGF, VEGF, and TGF-β level in plasma after different types of liver resection are shown in Fig. 4. The concentrations of HGF, VEGF, and TGF-β in plasma were measured by ELISA. HGF level reached its peak value on day 3 after minor and major resection. After repeated minor resection, HGF level reached a peak value on day 10. There was no difference in peak value among minor, repeated, and major resections (minor liver resection: 12.5±1.46 ng/ml, repeated minor liver resection: 12.7±1.67 ng/ml, major liver resection: 13.0±1.35 ng/ml, respectively, p = n.s. Fig. 4A). After minor and repeated resection, VEGF levels decreased on day 7. However, after major resection, VEGF level maintained a higher level than the other groups on day 7 (minor liver resection: 214.5±78.3 pg/ml, repeated minor liver resection: 225.3±65.8 pg/ml, major liver resection: 376.7±74.3 ng/ml, major liver resection vs repeated minor liver resection: p = 0.049, major liver resection vs minor liver resection: p = 0.025, Fig. 4B). The TGF-β level reached its peak value on day 10 after minor and repeated resection and decreased on day 14. After major resection, however, TGF-β level reached its peak value on day 14 and its level was significantly higher than the maximum value of other groups (minor liver resection: 2260.9±172.5 pg/ml on day 10, repeated minor liver resection: 3018.1±876.0 pg/ml on day 10, major liver resection: 4324.4±274.9 pg/ml on day 14, major liver resection vs repeated minor liver resection: p = 0.039, major liver resection vs minor liver resection: p = 0.003, Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

The time-course of changes in HGF (A), VEGF (B), and TGF-β (C) level in plasma after liver resection. The concentrations of HGF, VEGF, and TGF-β in plasma were measured by ELISA. (A) HGF level reached its peak value on day 3 after minor and major resection. But after repeated resection, HGF level reached a peak value on day 10. There were no difference in peak values among all groups (p = n.s.). (B) After minor and repeated resection, VEGF levels decreased on day 7. However, after major resection, the VEGF level maintained higher levels than the levels of the other groups on day 7 (*: p = 0.049 versus repeated minor liver resection, **: p = 0.025 versus minor liver resection). (C) TGF-β level reached its peak value on day 10 after minor and repeated resection and decreased on day 14. However, after major resection, the TGF-β level reached a peak value on day 14, which was significantly higher than the maximum value of other groups (*: p = 0.039 versus repeated minor liver resection on day 10, **: p = 0.003 versus minor liver resection on day 10). Five mice were used each day for each group. All graphs show mean ± SD.

DISCUSSION

Tumor recurrence in the liver has been linked to several factors, including inaccurate preoperative staging and presence of residual cancer in resection margins. Another factor may be the type of liver resection which may stimulate occult tumor growth at both intrahepatic and extrahepatic sites.

Other studies have shown that liver resection does not result in tumor stimulation. However, in all these studies, the resections performed were less than 50% hepatectomies and would be considered as minor resections [26, 27].

In the present study, powerful color-coded mouse models and imaging technologies were used to investigate the effects of different types of liver resection on the growth and metastases of colorectal tumors in the liver and the lung. The role of liver resection type on metastasis stimulation was examined by performing a sham operation, minor resection (35%), repeated minor resection (35% + 35%) and major resection (70%). In the present study, tumor growth was measured by fluorescence imaging. We have previously validated this method to measure tumor growth. A future study will focus on the cell biology of tumor response after liver resection and mitosis will be studied using cancer cells expressing GFP in the nucleus and RFP in the cytoplasm [21, 31].

Although major and repeated minor resection removed the same volume of liver parenchyma, only major resection stimulated lung and liver metastatic growth as well as recruitment of host-derived stroma. In contrast to major resection, animals which underwent repeated minor resection did not have stimulation of metastatic lung and liver tumors or stromal recruitment. Furthermore, there was no significant difference between repeated minor resection and minor resection in metastatic tumor growth and recruitment of host-derived stroma. In the present study we wanted to show that the livers were comparable in weight among all groups 14 days after resection. More detailed cellular experiments of the regenerating liver will be the focus of a future study. Color–coded imaging of an RFP-expressing host and GFP-labeled cancer cells demonstrated that host-derived stroma recruitment was stimulated by major resection more than minor and repeated minor resection. We have shown that major liver resection induces a strong stromal-recruitment response compared to a sham operation or minor repeated micro resections. We used color-coded imaging whereby tumors expressed GFP and stroma expressed RFP to visualize this spectacular stromal recruitment in the tumor after major liver resection. These results suggest an important role for the stroma. A future study will focus on the actual role of the stroma on tumor growth stimulated by major liver resection.

After major resection, plasma VEGF maintained a higher level than the other groups and peak value of plasma TGF-β was highest in the major resection group. Furthermore, the time-course of growth factors after repeated minor resection was different from that of after major resection even though same volume of liver parenchyma was excised in both surgical procedures. The growth-factor pattern after repeated minor resection was similar to that of minor resection (Fig. 4). These results suggest that major resection stimulates secretion of TGF-β more than repeated minor resection, which may promote stroma recruitment and growth. The accelerated recruitment of host-derived stroma after major resection may promote growth of the metastatic tumors.

The results of the present study show that repeated minor resection of the liver is much safer regarding metastatic tumor stimulation than major resection. Thus, stimulation of metastasis tumor depends not on the frequency or the total volume of resected liver but on the extent of liver resection that occurs at one time.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated the effects of various types of liver resection on the growth of liver and the lung metastatic tumors using GFP-expressing cancer cells and RFP transgenic nude mice to measure the cancer cell growth and stromal recruitment, respectively, by color-coded imaging. Color-coded imaging using an RFP expressing host and GFP labeled cancer cells is highly effective in visualizing tumor–host interaction. The results of this study indicate that when liver resection is necessary, repeated minor liver resection is superior to major liver resection, since major resection stimulates metastasis. Host-derived stroma density, which is stimulated by major resection, may affect and have an important role in growth of the metastatic tumors. Stromal recruitment and growth may depend on stimulation of TGF-β by a large one-time liver resection. These findings contribute to further understanding and surgical strategy for liver metastases. From our findings, the smaller the extent of one-time liver resection, the less stimulation of growth of any remaining tumor in the liver or at distant sites. We suggest that multiple wedge resection may be is preferable to lobectomy for single-lobe disease, and staged operations may be advantageous to extended lobectomy (major liver resection) for metastatic bilobar metastatic disease.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This study was supported in part by the National Cancer Institute grant CA132971.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Poon R, Fan ST, Lo CM, et al. Improving survival results after resection of hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective study of 377 patients over 10 years. Ann Surg. 2001;234:63. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200107000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenberg SA, editor. Surgical Treatment of Metastatic Cancer. J.B. Lippincott; Philadelphia: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adam R, Laurent A, Azoulay D, et al. Two-stage hepatectomy: a planned strategy to treat irresectable liver tumors. Ann Surg. 2000;232:777. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200012000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adam R, Bismuth H, Castaing D, et al. Repeat hepatectomy for colorectal liver metastases. Ann Surg. 1997;225:51. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199701000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hughes KS, Simon R, Songhorabodi S, et al. Resection of the liver for colorectal carcinoma metastases: a multi-institutional study of patterns of recurrence. Surgery. 1986;100:278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ercolani G, Grazi GL, Ravaioli M, et al. Liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma on cirrhosis: univariate and multivariate analysis of risk factors for intrahepatic recurrence. Ann Surg. 2003;237:536. doi: 10.1097/01.SLA.0000059988.22416.F2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ikeda Y, Matsumata T, Takenaka K, et al. Preliminary report of tumor metastasis during liver regeneration after hepatic resection in rats. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1995;21:188. doi: 10.1016/s0748-7983(95)90468-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mizutani J, Hiraoka T, Yamashita R, et al. Promotion of hepatic metastases by liver resection in the rat. Br J Cancer. 1992;65:794. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1992.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jiang W, Hiscox S, Matsumoto K, Nakamura T. Hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor, its molecular, cellular and clinical implications in cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 1999;29:209. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(98)00019-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lukomska B, Dluzniewska J, Polanski J, Zajac L. Expression of growth factors in colorectal carcinoma liver metastatic patients after partial hepatectomy: implications for a functional role in cell proliferation during liver regeneration. Comp Hepatol. 2004;3(Suppl 1):S52. doi: 10.1186/1476-5926-2-S1-S52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoon SS, Kim SH, Gonen M, et al. Profile of plasma angiogenic factors before and after hepatectomy for colorectal cancer liver metastases. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:353. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2006.03.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chishima T, Miyagi Y, Wang X, et al. Cancer invasion and micrometastasis visualized in live tissue by green fluorescent protein expression. Cancer Res. 1997;57:2042. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang M, Baranov E, Jiang P, et al. Whole-body optical imaging of green fluorescent protein-expressing tumors and metastases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:1206. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.3.1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoffman RM. The multiple uses of fluorescent proteins to visualize cancer in vivo. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:796. doi: 10.1038/nrc1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang M, Reynoso J, Bouvet M, Hoffman RM. A transgenic red fluorescent protein-expressing nude mouse for color-coded imaging of the tumor microenvironment. J Cell Biochem. 2009;106:279. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang M, Li L, Jiang P, et al. Dual-color fluorescence imaging distinguishes tumor cells from induced host angiogenic vessels and stromal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:14259. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2436101100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang M, Reynoso J, Jiang P, et al. Transgenic nude mouse with ubiquitous green fluorescent protein expression as a host for human tumors. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8651. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tran Cao HS, Reynoso J, Yang M, et al. Development of the transgenic cyan fluorescent protein (CFP)-expressing nude mouse for “Technicolor” cancer imaging. J Cell Biochem. 2009;107:328. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoffman RM, Yang M. Color-coded fluorescence imaging of tumor-host interactions. Nature Protocols. 2006;1:928. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoffman RM, Yang M. Whole-body imaging with fluorescent proteins. Nature Protocols. 2006;1:1429. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoffman RM, Yang M. Subcellular imaging in the live mouse. Nature Protocols. 2006;1:775. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vintersten K, Monetti C, Gertsenstein M, et al. Mouse in red: red fluorescent protein expression in mouse ES cells, embryos, and adult animals. Genesis. 2004;40:241. doi: 10.1002/gene.20095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Higgins GM, Anderson RM. Experimental pathology of the liver. Arch Pathol. 1931;12:186. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yamauchi K, Yang M, Jiang P, et al. Development of real-time subcellular dynamic multicolor imaging of cancer-cell trafficking in live mice with a variable-magnification whole-mouse imaging system. Cancer Res. 2006;66:4208. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang M, Jiang P, Hoffman RM. Whole-body subcellular multicolor imaging of tumor-host interaction and drug response in real time. Cancer Res. 2007;67:5195. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Castillo MH, Doerr RJ, Paolini N, Jr, et al. Hepatectomy prolongs survival of mice with induced liver metastases. Arch Surg. 1989;124:167. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1989.01410020037005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ono M, Tanaka N, Orita K. Complete regression of mouse hepatoma transplanted after partial hepatectomy and the immunological mechanism of such regression. Cancer Res. 1986;46:5049. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Byrne AM, Bouchier-Hayes DJ, Harmey JH. Angiogenic and cell survival functions of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) J Cell Mol Med. 2005;9:777–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2005.tb00379.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Olumi AF, Grossfeld GD, Hayward SW, Carroll PR, Tlsty TD, Cunha GR. Carcinoma-associated fibroblasts direct tumor progression of initiatedhuman prostatic epithelium. Cancer Res. 1999;59:5002–5011. doi: 10.1186/bcr138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Orimo A, Gupta PB, Sgroi DC, et al. Stromal fibroblasts present in invasive human breast carcinomas promote tumor growth and angiogenesis through elevated SDF-1/CXCL12 secretion. Cell. 2005;121:335–348. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Katz MH, Takimoto S, Spivack D, Moossa AR, Hoffman RM, Bouvet M. A novel red fluorescent protein orthotopic pancreatic cancer model for the preclinical evaluation of chemotherapeutics. J. Surg. Res. 2005;113:151–160. doi: 10.1016/s0022-4804(03)00234-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]