Abstract

It is recommended that all pregnant women should receive a comprehensive oral health evaluation because poor maternal oral health may affect pregnancy outcomes and the general health of the woman and her baby. Midwives are well placed to provide dental health advice and referral. However, in Australia, little emphasis has been placed on the educational needs of midwives to undertake this role. This article outlines the development of an online education program designed to improve midwives’ dental health knowledge, prepare them to assess the oral health of women, refer when required, and provide appropriate dental education to women and their families. The program consists of reading and visual material to assist with the oral health assessment process and includes competency testing.

Keywords: perinatal oral health, midwives, antenatal care, childbirth education

Maintaining oral health during pregnancy is important, and new perinatal guidelines strongly recommend that prenatal care providers such as midwives play an active role in promoting maternal oral health (California Dental Association Foundation, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, District IX, 2010; Ressler-Maerlender, Krishna, & Robinson, 2005). Midwives are in a unique position to assess and refer pregnant women with oral health problems to a dental professional. Many countries, including Australia, have positioned midwives to take up this role (Carl, Roux, & Metacale, 2000; Mills & Moses, 2002; Stevens, Iida, & Ingersoll, 2007), but there appears to have been little focus on the educational preparation of midwives for this role. This article describes the development of an online oral health education program targeting busy midwives who undertake antenatal care.

BACKGROUND

Expectant women are particularly at risk for poor oral health because of hormonal changes during pregnancy, and poor oral health can have a significant impact on the health of both the mother and baby (Silk, Douglass, Douglass, & Silk, 2008). Poor maternal oral health increases the risk of babies’ developing early dental caries and is linked to adverse pregnancy outcomes such as preterm birth and birth of low birth weight babies (George, Shamin, et al., 2011; López, Smith, & Guiterrez, 2002; Yost & Li, 2008). The major mechanism by which children acquire cariogenic bacteria (bacteria causing tooth decay) is through the direct transmission of infected saliva as a result of untreated caries from mother to child (Yost & Li, 2008). Mothers who have untreated dental caries after birth are at a higher risk for passing on cariogenic bacteria to their children, particularly if the mothers engage in inappropriate feeding practices such as sharing a spoon when tasting baby food, cleaning a dropped pacifier by mouth, or wiping the baby’s mouth with saliva (Barber & Wilkins, 2002; Berkowitz, 2003; Gussy, Waters, Walsh, & Kilpatrick, 2006; New York State Department of Health, 2006).

Although debate continues over the causal link between poor oral health and pregnancy outcomes, various countries have implemented preventive strategies to maintain the oral health of mothers during pregnancy (George, Johnson, Blinkhorn, et al., 2010). However, in Australia, no such strategies have been put into practice (George, Johnson, Blinkhorn, et al., 2010; George, Johnson, Ellis, et al., 2010). Compounding the issue in Australia is the limited access to public dental services and the high cost of private dental treatment (New South Wales Parliament, 2006). Although Australia follows a universal health-care system that ensures all Australians have access to free or low-cost medical care (Australian Government Department of Human Services, 2011), free public dental services are only available to low-income earners (New South Wales Health, 2009). Furthermore, because of the lengthy waiting times to access public dental services, less than 10% of the population who are eligible for such services are able to access them (New South Wales Parliament, 2006).

Poor maternal oral health increases the risk of babies’ developing early dental caries and is linked to adverse pregnancy outcomes such as preterm birth and birth of low birth weight babies.

To further explore the potential of using midwives to promote perinatal oral health and refer women to dentists, several initial research studies were undertaken that have informed the education approach. These studies were approved by the Sydney South West Area Health Service Human Research Ethics Committee. Initially, semistructured interviews with 10 women from the local antenatal clinic were undertaken (George, Ajwani, et al., 2010). The women ranged in age from 18 to 30 years, with two of them being primiparous. All except one were in their second or third trimesters of pregnancy. Six of the pregnant women confirmed that they had oral health problems. None of the women had received regular dental care, and the pregnant women identified numerous barriers in maintaining their oral health, such as lack of awareness, safety concerns, cost of treatment, and access to dental care. All women participating in the study were receptive to midwives’ providing oral health education. A further survey of 241 pregnant women attending the antenatal clinic found that more than 50% (n = 130) of the women had dental problems, with 68% or more of the women having not visited a dentist in the last 6 months, and 90% having no information on oral health and pregnancy (Bhole et al., 2010). Again, most women (n = 218; 90%) were receptive to midwives’ providing oral health education, assessment, and referrals.

Focus group interviews with 15 midwives from the local antenatal clinic were undertaken to assess their perceptions and concerns regarding promoting oral health and referring women to dentists during the antenatal period (George, Johnson, et al., 2011). The midwife participants ranged in age from 28 to over 50 years and had between 3 and 30 years of midwifery experience. The midwives suggested that a quarter of their patients had poor oral health, and they also reported a lack of knowledge about the impact of poor oral health during pregnancy on the mother and baby. Most midwives were receptive to providing dental health advice, conducting oral health assessments, and referring mothers for a dental checkup. However, potential barriers were identified, including the need for further education and assessment of the midwives’ competence to conduct oral assessments and the need for dental services to be available for low-income families frequently seen at the antenatal clinics. The midwives suggested that incentives such as continuing professional development (CPD) points (necessary for continued registration) be made available to midwives participating in the education program. It was also suggested that the program be computer-based so that midwives could access the program during work time and complete it at their own pace. Midwives requested that competency testing be included in the program because it would contribute to their confidence to deliver a new service.

Education Strategies

A computer-based system is a practical approach because online learning is convenient and flexible (Ali, Hodson-Carlton, & Ryan, 2004). Health professionals face challenges in accessing education, particularly continuing education; thus, Web-based learning is an ideal medium (Atack & Rankin, 2002). In addition, computer-based education has other positive effects. In a meta-analysis of 201 eligible studies, which included health-care professionals’ use of Internet education, Cook et al. (2008) concluded that regardless of the context, topic, learning outcome, or category of learner, all studies were associated with positive outcomes.

Some studies, however, have found that online learning can be problematic. For example, in a study exploring the impact of registered nurses completing a 6-month computer-based course from their workplace, Atack (2003) found several problems. The nurses’ difficulties included limited access to computers and the Internet; the chaotic, intense, and irregular nature of their work duties; and lack of time in which to undertake the course. Many of the nurses remained at work at the end of their shift to do their studies, whereas others completed their studies at home. Ali et al. (2004) also identified that accessing computers and especially the Internet for study purposes at work is difficult for some nurses.

Gerrish et al. (2006) also found that barriers to midwives’ and nurses’ use of computers at work include not enough time, insufficient computers, and nonsupportive colleagues. Negative attitudes from colleagues regarding undertaking computer-based study in the workplace must change in the near future as health professionals, especially in Australia, adapt to legal changes requiring lifelong learning. Under the Health Practitioner Regulation National Law Act 2009 (Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency, 2010), continuing education for the annual renewal of registration has become a standard requirement for Australian midwives (Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia, 2010). Midwives now are required to provide evidence each year that they have completed a minimum of 20 hours of approved professional development that is relevant to their area of practice. To help midwives prepare for the new standard, the Australian College of Midwives (2009a) improved the professional development section on its website. This section provides information to midwives about areas for professional development and examples of e-learning courses. Furthermore, to support online learning, the college has developed a “learning seat” page with a link to an introduction to e-learning using an online tutorial (Australian College of Midwives, 2009b). This learning opportunity supports midwives who may lack confidence in the area of online education.

The development and examination of theoretical material using online access is well established (Schmidt, Ralph, & Buskirk, 2009); however, the midwives in our focus group indicated that they wanted the program to be entirely computer-based, including the skills assessment. Examinations using multiple-choice questions related to behavioral data in video clips have been successfully used in psychology (Hertenstein & Wayand, 2008), and Barratt (2010) reported that videos relating to skills helped nurses reinforce what they had learned. The existing literature, in combination with these research findings, shaped the scope of the content, the teaching approach, and the form of the competency assessment of the online dental education program for midwives.

PROGRAM DEVELOPMENT

The dental education program for midwives was designed to provide the required background education and practical assessment skills prior to implementing a Midwifery Initiated Oral Health (MIOH) pilot program on low-risk pregnant women in South West Sydney. The MIOH program focuses on education about dental health plus oral health screening, with referral for women identified with oral health problems.

The dental education program was developed in consultation with an expert panel comprised of midwives, nurses, dentists, and academics in these respective disciplines. The key task in the development of the program was to agree on a specific midwifery competency in oral health. The final competency was determined: The midwife has the knowledge and skills to undertake oral cavity screenings on pregnant women, refer if appropriate, and provide the women with relevant evidenced-based information to promote good oral maternal and infant health. Another important task was to develop a referral pathway. The expert panel discussed numerous draft ideas, which resulted in the development of the “Oral Assessment Pathways for Midwives” document.

Theoretical Framework

Three theoretical frameworks influenced the development of the MIOH program. The theory of constructive alignment (Biggs & Tang, 2007) was chosen because it provides a framework for aligning learning outcomes with learning activity and assessment methods. Knowles’ (1990) andragogy theory of adult learning was also an important framework because the midwives were adult learners with professional midwifery experience. Most of the concepts that Knowles identified about adult learners fit with the characteristics of Australian midwives. That is, as adults, Australian midwives have life and professional experiences; they are motivated to learn because learning can satisfy their needs for professional development; and learning is a lifelong endeavor for midwives in Australia because they are required to complete professional development education and, furthermore, because of this requirement, midwives can achieve self-direction in their learning.

The third model that influenced the development of the MIOH program was Mezirow’s (2000, 2003) transformational learning theory, which describes how critical reflection influences how adults learn. This theory was an important concept in the development of the program because lifelong learning and the ability to reflect on practice is a requirement of many midwifery registration authorities (Nakielski, 2005) and is included in the Australian Nursing and Midwifery Council’s (2006) competency standards. It was therefore important that, in developing the education program, emphasis was placed on self-reflection. Professional practice challenges midwives to undertake critical thinking and problem solving in clinical practice (Riddell, 2007; Vacek, 2009).

The dental education program for midwives was also influenced in its online development by the work of Oliver (2000). This approach included using more controlled learning in the first part of the program but with areas for reflection because the learners were professionals already in practice; providing plenty of resources; making sure the learning activities within each module directly influenced the learning outcomes; and creating appropriate contexts (in our case, antenatal clinic settings) so the learning would be meaningful.

Program Content

A modular approach to the dental education program for midwives was the underlying structure because it allows midwives to undertake short learning periods when opportunities occur within the working day. The nature of midwives’ work in busy antenatal clinics can be demanding, depending on the number of women attending the clinic, the staff available, and the levels of activity in other areas of the maternity unit. This busy setting is similar to that of nurses, where working situations can be hectic (Atack, 2003).

The education program comprises three modules, which are designed to meet the theoretical and practical requirements to fulfill the competency. Each module includes aims and learning outcomes as well as required reading activities to undertake reflective exercises and review questions (Figures 1 and 2). Full details for other suggested reading materials and online resources, such as videos on YouTube, are also included. In addition, the program includes a copy of the “Oral Assessment Pathways for Midwives” document and examples of referral letters midwives can use.

The final aspect of the program is to seek feedback from the participants’ experience in order to assess the program’s effectiveness and, if necessary, to apply modifications and changes. The program includes two avenues for providing feedback. One is a feedback form that is available to each midwife on the completion of the modules. The form asks several questions, including what the midwife considered the best aspect of the program and what required improvement, and requests any other comments. Alternatively, the midwife can place a direct phone call or send an e-mail to the program coordinator.

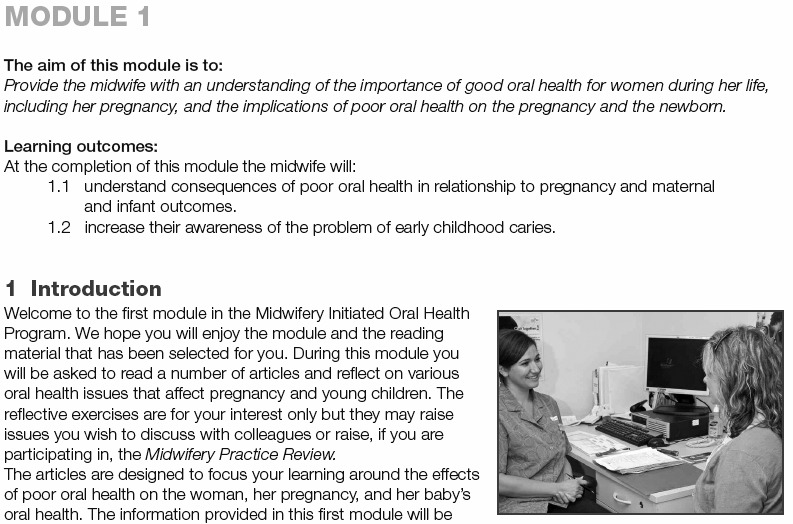

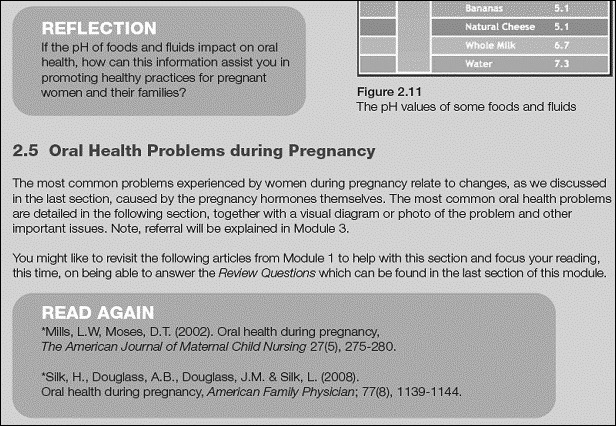

The first module of the education program focuses on background information about research that addresses the current state of oral health among pregnant women and children (Figure 1). The second module reviews some of the basic anatomy and physiology of the oral cavity and how pregnancy changes the oral environment (Figure 2). It also provides visual examples of healthy and unhealthy oral conditions.

Figure 1.

Snapshot of first module of the online education program.

Copyright 2010 by Centre for Applied Nursing Research. Reproduced with permission.

Figure 2.

Snapshot of second module of the online education program.

Copyright 2010 by Centre for Applied Nursing Research. Reproduced with permission.

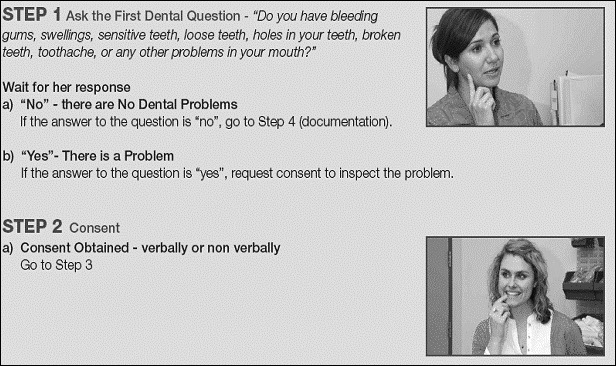

The third module relates specifically to the oral health screening skill and the referral process. It explains the questions midwives need to ask pregnant women about their oral health, and the answers are related to the screening and referral pathway. The skill is presented in a step-by-step approach, using photos taken for the project (Figure 3). The module also contains scenarios that provide midwives a further guide for practice and critical reflection.

Figure 3.

Snapshot of third module of the online education program.

Copyright 2010 by Centre for Applied Nursing Research. Reproduced with permission.

The modules were designed to allow midwives to complete each module within approximately 3–4 hours of study time, providing a total of 12 program hours. Supplying essential reading literature is important because it enables midwives to read articles or sections of an article at their own convenience. The developers of the program were also mindful that some individuals might be “visual learners” (Hertenstein & Wayand, 2008). Therefore, photographs are used extensively throughout the modules and were taken, using professional models, to illustrate key steps (Figure 3). We obtained permission to reproduce images and content from journal articles, which are acknowledged within the program documentation.

An example of a freely accessible YouTube video that provides information about the structure of a tooth is available at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T3E77eRM9qU&feature=related

Videos for training, reinforcing content, or enhancing a topic during educational sessions have been used for many years (Berk, 2009); therefore, the dental education program also uses the video medium. However, major cost implications arise when multimedia technologies are used (Lynn & MacFarlane, 2009). The cost of including videos in an educational program can be reduced by using video-sharing websites such as YouTube.

Although videos are expensive to produce and film, the costs can be offset as the video is used over time. Furthermore, using video in distance-learning programs to teach practical skills has been found to be more effective than using print-based material (Donkor, 2010). To assist midwives in developing the skill of conducting an oral health assessment, a 5-minute video was developed as part of the MIOH education program. The video was filmed in the antenatal setting and features professional actors who play the roles of a presenter, a midwife, and a pregnant woman. The video shows a midwife conducting a dental assessment during an antenatal care visit with a pregnant woman and providing her with oral health promotional material. The midwifery oral health assessment video was designed to enhance the midwives’ learning during the MIOH education program and help in their competency assessments.

To view an excerpt from the 5-minute midwifery oral health assessment video, go online to http://www.sswahs.nsw.gov.au/SSWAHS/CANR/video/short.html

Assessing Competency

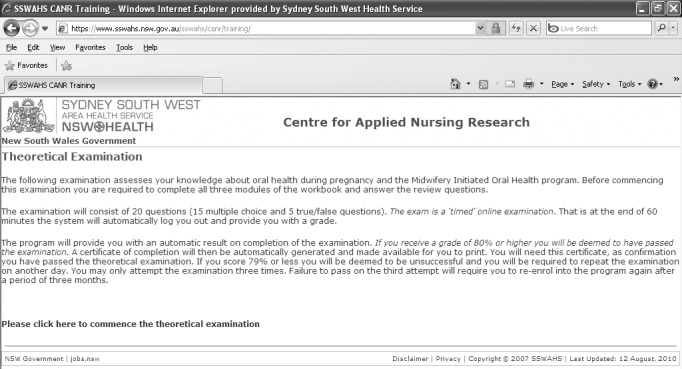

The competency assessments, as requested by the midwives in the focus group, were developed to include online theoretical and skill assessment examinations. Upon completion of the module work and at their convenience, midwives complete the online theoretical examination, consisting of multiple-choice questions and true or false questions. The examination can be accessed online via the “Examination” link on the Centre for Applied Nursing Research website, and each midwife has her own password to access the examination (Figure 4). After completing the examination, the midwife receives an instant result. If the result is “pass,” she can print out a certificate of completion.

Figure 4.

Snapshot of the online theoretical examination.

Copyright 2010 by Centre for Applied Nursing Research. Reproduced with permission.

An example of the promotional material provided in the midwifery oral health assessment video is the Keep Smiling While You Are Pregnant brochure, which is available from the New South Wales Department of Health website (http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/resources/cohs/pdf/keep_smiling_pregnant.pdf).

After the midwife successfully completes the theoretical examination, she undertakes a skill assessment. The skill assessment requires the viewing of a specifically prepared video of an oral health review. The midwife then answers a short examination consisting of multiple-choice questions relevant to the skill shown in the video. The skill assessment is also marked automatically online; thus, an immediate result is given and, if the midwife successfully passes, a certificate of completion can be printed.

Midwives who are unsuccessful in passing either the theoretical or skill assessment examination have the opportunity to resit the examinations at their convenience. They are permitted two further attempts in both the theoretical and skill assessments before the system blocks access. To maintain consistency, both assessments are designed to be “timed” examinations with an automatic lockout after a preset period. The theoretical examination has a preset time of 60 min, and the skill assessment examination has a preset time of 30 min. Both examinations are randomly generated from a bank of questions each time an examination is attempted to ensure that each resit examination has a different set of questions.

Review and Revision

After final editing, the draft program, including the pilot video via a website, was sent out to eight clinical and academic health professionals for review. Feedback was highly positive for both the program and the video. Some editing of the draft program and suggested changes in the layout and design, using professional developers, were made. The changes included correcting grammar and punctuation errors, increasing font size, modifying the background color scheme, and improving clarity of the images.

A trial of the education program was undertaken with 26 midwives who work in maternity practice at a large hospital in South West Sydney. Of the 26 midwives, 85% (n = 22) successfully passed the education program. The midwives achieved an average competency of 83.6% (range 80%–95%) and 93.8% (range 80%–100%) for the theory and skill assessment examinations, respectively. Feedback data showed that all midwives were appreciative that the program was available online and self-paced. Most found the program extremely informative and were now more confident in promoting maternal oral health.

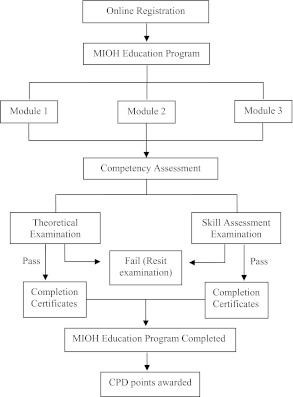

We approached the Australian College of Midwives after feedback from midwives indicated that the program should be allocated CPD points. The 26 midwives who passed the MIOH education program demonstrated that they met one or more of the Australian Nursing and Midwifery Council’s (2006) “National Competency Standards for the Midwife.” For example, Competency 14.1 ensures that midwives incorporate research evidence into practice by maintaining relevant and up-to-date research knowledge, discuss implications of evidence with colleagues and women, and support research in midwifery and maternity care. The MIOH education program meets the standards outlined in Competency 14.1 and has been endorsed by the Australian College of Midwives and awarded 16 CPD points. The program is available online (https://www.sswahs.nsw.gov.au/sswahs/canr/training/). An overview of the MIOH education program, including the competency assessments, is outlined in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Overview of the Midwifery Initiated Oral Health (MIOH) education program. CPD = continuing professional development.

DISCUSSION

The midwife-led focus group highlighted the need for developing an education program that provides background information about maternal oral health, an overview of dental problems childbearing women may encounter, and a specific validated tool for oral health screening as well as advice on referral pathways. Based on the initial positive feedback from midwives and other health professionals, the MIOH education program appears to have achieved its objectives, although more pilot testing is required.

The midwives requested an overall concept of a computer-based education program. Preliminary research, along with consultation with an expert panel, informed the framework, design, content, and competency testing of the dental health education program. The use of teaching strategies such as guided reading, reflection, online activities, and visual reinforcement were supported by previous research and are included in the program. One unexpected issue we encountered was obtaining copyright for the reading material and images used in the education program. Copyright compliance was more costly than expected and is an issue that needs to be seriously considered by researchers when budgeting for education programs.

The focus of many online education programs is to provide interactive learning such as practice exercises, discussions, or feedback, which can improve learning outcomes and the development of reflective thinking (Cook et al., 2010). Because of budget constraints, the MIOH project does not include interactive learning within the education program. Interactive learning includes activities such as word games or solving puzzles that confer instant feedback and online discussions that assist in improving critical thinking. However, the advantages of an online education program, which allows individuals to study at times convenient to themselves, probably outweigh some loss of critical thinking and reflection. Clearly, more evaluation of this program is required over time, but assessing clinical skills using a video and then answering multiple-choice questions is an underresearched area of training for all health professionals.

Improving awareness among pregnant women about the importance of maintaining oral health and using appropriate feeding practices could reduce the risks of their infants’ developing early dental decay.

For information about Kentucky’s use of CenteringPregnancySmiles to improve oral health, see http://www.ket.org/health/fixing-kys-smile.htm

Although the education program was developed initially to educate midwives prior to implementing the MIOH pilot program, it is an education initiative that would be suitable for midwives working in all areas of maternity care as well as for health professionals who conduct childbirth education and early-parenting classes. Improving awareness among pregnant women about the importance of maintaining oral health and using appropriate feeding practices could reduce the risks of their infants’ developing early dental decay. These preventative steps are important because dental caries remains the most common chronic childhood disease, occurring more frequently than asthma (Yost & Li, 2008). Furthermore, encouraging good oral hygiene practices among expectant mothers could reduce the incidence of preterm birth and low birth weight babies and indirectly influence the oral health behaviors of the mothers’ infant and other children. Current prenatal care programs that have integrated oral health education and treatment with routine prenatal care, such as the CenteringPregnancySmiles program in the United States, have demonstrated synergistic beneficial effects on birthing outcomes (Kovarik et al., 2009; Skelton et al., 2009).

The dental education program also has immense potential for use in other areas of midwifery in Australia and internationally. For example, it could be included in preregistration midwifery programs such as a Bachelor of Midwifery or Diploma of Midwifery. Additionally, the program could be used as a professional development activity for registered midwives in countries such as Canada, New Zealand, and the United States or in other English-speaking nations where midwives must continue to undertake professional education to maintain their registration to practice.

The MIOH education program is the first of its kind in Australia to provide vital knowledge and skills to midwives in promoting oral health among pregnant women. The program has potential for use in other areas of midwifery in Australia and internationally. It could be included in courses for student midwives and as a program for assisting midwives in other countries to maintain professional currency for continuing registration or licensing. Although the program requires further evaluation, it is a step in the right direction to addressing a neglected aspect of antenatal care.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We gratefully acknowledge The Centre for Oral Health Strategy (NSW) for funding to undertake this study.

Biography

AJESH GEORGE is a senior research fellow at the Centre for Applied Nursing Research for the South Western Sydney Local Health District and an adjunct fellow in the School of Nursing and Midwifery at the University of Western Sydney in Australia. MARGARET DUFF is a senior lecturer in the School of Nursing and Midwifery at the University of Western Sydney. SHILPI AJWANI is the head of Oral Health Research and Promotion for Sydney and South Western Sydney Local Health District Oral Health Services and Sydney Dental Hospital and a clinical senior lecturer in the faculty of dentistry at the University of Sydney. MAREE JOHNSON is the director of the Centre for Applied Nursing Research for the South Western Sydney Local Health District and a professor of nursing in the School of Nursing and Midwifery at the University of Western Sydney. HANNAH DAHLEN is an associate professor of midwifery in the School of Nursing and Midwifery, College of Health and Science, at the University of Western Sydney. ANTHONY BLINKHORN is the New South Wales chair of Population Oral Health in the faculty of dentistry at the University of Sydney. SHARON ELLIS is a midwifery nursing manager for antenatal services at Camden and Campbelltown Hospitals, South Western Sydney Local Health District. SAMEER BHOLE is the area clinical director for Sydney and South Western Sydney Local Health District Oral Health Services and Sydney Dental Hospital and a clinical associate professor in the faculty of dentistry at the University of Sydney.

REFERENCES

- Ali N. S., Hodson-Carlton K., Ryan M. (2004). Students’ perceptions of online learning: Implications for teaching. Nurse Educator, 29(3), 111–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atack L. (2003). Becoming a web-based learner: Registered nurses’ experiences. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 44(3), 289–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atack L., Rankin J. (2002). A descriptive study of registered nurses’ experiences with web-based learning. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 40(4), 457–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Australian College of Midwives (2009a). Welcome to the Australian College of Midwives. Retrieved from http://www.midwives.org.au/scripts/cgiip.exe/WService=MIDW/ccms.r

- Australian College of Midwives (2009b). Welcome to the Australian College of Midwives E-Learning Centre. Retrieved from http://www.learningseat.com/servlet/ShopFrontPage?companyId=acm

- Australian Government Department of Human Services (2011). Medicare. Retrieved from http://www.medicareaustralia.gov.au/public/register/index.jsp

- Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (2010). Health practitioner regulation national law act 2009 [Reprint]. Retrieved from http://www.ahpra.gov.au/Legislation-and-Publications/Legislation.aspx [PubMed]

- Australian Nursing and Midwifery Council (2006). National compentency standards for the midwife. Retrieved from http://www.anmc.org.au/userfiles/file/competency_standards/Competency%20standards%20for%20the%20Midwife.pdf

- Barber L. R., Wilkins E. M. (2002). Evidence-based prevention, management, and monitoring of dental caries. The Journal of Dental Hygiene, 76(4), 270–275 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barratt J. (2010). A focus group study of the use of video-recorded simulated objective structured clinical examinations in nurse practitioner education. Nurse Education in Practice, 10(3), 170–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berk R. A. (2009). Multimedia teaching with video clips: TV, movies, YouTube, and mtvU in the college classroom. [Article] International Journal of Technology in Teaching & Learning, 5(1), 1–21 [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz R. J. (2003). Acquisition and transmission of mutans streptococci. Journal of the California Dental Association, 31(2), 135–138 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhole S., Ajwani S., George A., Johnson M., Blinkhorn A., Ellis S. (2010). Oral health care model for pregnant women in Southwest Sydney. Journal of Dental Research, 89, Abstract 138958. Retrieved from http://www.dentalresearch.org [Google Scholar]

- Biggs J., Tang C. (2007). Teaching for quality learning at university (3rd ed.). Berkshire, UK: Open University Press/McGraw-Hill Education [Google Scholar]

- California Dental Association Foundation, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, District IX (2010). Oral health during pregnancy and early childhood: Evidence-based guidelines for health professionals. Journal of the California Dental Association, 38(6), 391–403, 405–440 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carl D. L., Roux G., Matacale R. (2000). Exploring dental hygiene and perinatal outcomes. Oral health implications for pregnancy and early childhood. AWHONN Lifelines, 4(1), 22–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook D. A., Levinson A. J., Garside S., Dupras D. M., Ewin P. J., Montori V. M. (2008). Internet-based learning in the health professions: A meta-analysis. Journal of American Medical Association, 300(10), 1181–1196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook D. A., Levinson A. J., Garside S., Dupras D. M., Erwin P. J., Montori V. M. (2010). Instructional design variations in Internet-based learning for health professions education: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Academic Medicine, 85(5), 909–922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donkor F. (2010). The comparative instructional effectiveness of print-based and video-based instructional materials for teaching practical skills at a distance. International Review of Research in Open & Distance Learning, 11(1), 96–115 [Google Scholar]

- George A., Ajwani S., Bhole S., Johnson M., Blinkhorn A., Ellis S. (2010). Promoting perinatal oral health in South-western Sydney: A collaborative approach. Journal of Dental Research, 89, Abstract 142301. Retrieved from http://www.dentalresearch.org [Google Scholar]

- George A., Johnson M., Blinkhorn A., Ellis S., Bhole S., Ajwani S. (2010). Promoting oral health during pregnancy: Current evidence and implications for Australian midwives. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 19(23–24), 3324–3333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George A., Johnson M., Duff M., Blinkhorn A., Ajwani S., Bhole S., Ellis S. (2011). Maintaining oral health during pregnancy: Perceptions of midwives in Southwest Sydney. Collegian, 18(2), 71–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George A., Johnson M., Ellis S., Dahlen H., Blinkhorn A., Bhole S., Ajwani S. (2010). Promoting dental health in pregnant women: A new role for midwives in Australia. Australian Nursing Journal, 18(1), 37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George A., Shamim S., Johnson M., Ajwani S., Bhole S., Blinkhorn A., Andrews K. (2011). Periodontal treatment during pregnancy and birth outcomes: A meta-analysis of randomised trials. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare, 9(2), 122–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerrish K., Morgan L., Mabbott I., Debbage S., Entwistle B., Ireland M., Warnock C. (2006). Factors influencing use of information technology by nurses and midwives. Practice Development in Health Care, 5(2), 92–101 [Google Scholar]

- Gussy M. G., Waters E. G., Walsh O., Kilpatrick N. M. (2006). Early childhood caries: Current evidence for aetiology and prevention. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 42(1–2), 37–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertenstein M. J., Wayand J. F. (2008). Video-based test questions: A novel means of evaluation. Journal of Instructional Psychology, 35(2), 188–191 [Google Scholar]

- Knowles M. (1990). The adult learner: A neglected species (4th ed.). Houston, TX: Gulf Publishing Company [Google Scholar]

- Kovarik R. E., Skelton J., Mullins M. R., Langston L., Womack S., Morris J., Ebersole J. L. (2009). CenteringPregnancySmiles: A community engagement to develop and implement a new oral health and prenatal care model in rural Kentucky. Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement, 13(3), 101–112 [Google Scholar]

- López N. J., Smith P. C., Gutierrez J. (2002). Higher risk of preterm birth and low birth weight in women with periodontal disease. Journal of Dental Research, 81(1), 58–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynn J., MacFarlane A. (2009). A digital media e-learning training strategy for healthcare employees: Cost effective distance learning by collaborative offline/online engagement and assessment. Proceedings of World Academy of Science: Engineering & Technology, 41, 886–890 [Google Scholar]

- Mezirow J. (Ed.). (2000). Learning as transformation: Critical perspectives on a theory in progress. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass [Google Scholar]

- Mezirow J. (2003). Transformative learning as discourse. Journal of Transformative Education, 1(1), 58–63 [Google Scholar]

- Mills L. W., Moses D. T. (2002). Oral health during pregnancy. American Journal of Maternal Child Nursing, 27(5), 275–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakielski K. P. (2005). The reflective practitioner. In Raynor M. D., Marshall J. E., Sullivan A. (Eds.), Decision making in midwifery practice (pp. 143–156). Edinburgh, Scotland: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone [Google Scholar]

- New South Wales Health (2009). Oral health—Eligibility of persons for public oral health care in NSW (PD2009_074). Retrieved from http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/policies/pd/2009/pdf/PD2009_074.pdf

- New South Wales Parliament (2006, March). Dental services in NSW: Report by Standing Committee on Social Issues p. 13. Retrieved from http://www.parliament.nsw.gov.au/prod/parlment/committee.nsf/0/46F0901A5E311E86CA256FE4000BE787

- New York State Department of Health (2006). Oral health care during pregnancy and early childhood: Practice guidelines (No. 0824) Albany, NY: Author [Google Scholar]

- Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia (2010). Registration standards. Retrieved from http://www.nursingmidwiferyboard.gov.au/Registration-Standards.aspx

- Oliver R. (2000). When teaching meets learning: Design principles and strategies for Web-based learning environments that support knowledge construction. In Sims R., O’Reilly M., Sawkins S. (Eds.), Learning to choose: Choosing to learn. Proceedings of the 17th Annual ASCILITE Conference (pp. 17–28). Lismore, NSW, Australia: Southern Cross University Press [Google Scholar]

- Ressler-Maerlender J., Krishna R., Robinson V. (2005). Oral health during pregnancy: Current research. Journal of Women’s Health (Larchmont), 14(10), 880–882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riddell T. (2007). Critical assumptions: Thinking critically about critical thinking. Journal of Nursing Education, 46(3), 121–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt M. P., Ralph D. L., Buskirk B. (2009). Using online exams: A case study. Journal of College Teaching & Learning, 6(8), 1–8 Retrieved from http://journals.cluteonline.com/index.php/TLC/article/view/1108 [Google Scholar]

- Silk H., Douglass A. B., Douglass J. M., Silk L. (2008). Oral health during pregnancy. American Family Physician, 77(8), 1139–1144 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skelton J., Mullins R., Langston L. T., Womack S., Ebersole J. L., Rising S. S., Kovarik R. (2009). CenteringPregnancySmiles: Implementation of a small group penatal care model with oral health. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 20, 545–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens J., Iida H., Ingersoll G. (2007). Implementing an oral health program in a group prenatal practice. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing, 36(6), 581–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vacek J. E. (2009). Using a conceptual approach with concept mapping to promote critical thinking. Journal of Nursing Education, 48(1), 45–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yost J., Li Y. (2008). Promoting oral health from birth through childhood: Prevention of early childhood caries. The American Journal of Maternal Child Nursing, 33(1), 7–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]