Abstract

A genetic factor model is introduced for decomposition of group differences of the means of phenotypic behavior as well as individual differences when the research variables under consideration are ordered categorical. The model employs the general Genetic Factor Model proposed by Neale and Cardon (Methodology for genetic studies of twins and families, 1992) and, more specifically, the extension proposed by Dolan et al. (Behav Genet 22: 319–335, 1992) which enables decomposition of group differences of the means associated with genetic and environmental factors. Using a Latent Response Variable (LRV) formulation (Muthén and Asparouhov, Latent variable analysis with categorical outcomes: multiple-group and growth modeling in Mplus. Mplus web notes: No. 4, Version 5, 2002), proportional differences of response categories between groups are modeled within the genetic factor model in terms of the distributional differences of latent response variables assumed to underlie the observed ordered categorical variables. Use of the proposed model is illustrated using a measure of conservatism in the data collected from the Australian Twin Registry.

Keywords: genetic factor model, latent response variable formulation, ordered categorical variables, Mplus, twins

The genetic factor model is used in behavior genetics to determine the relative contributions of genetic and environmental components on a phenotypic behavior (Martin and Eaves 1977; Neale and Cardon 1992). In its basic form, the genetic factor model is an application of multiple-group confirmatory factor analytic models that decomposes variances of observed phenotypic variables into genetic and environmental factors with genetically informative data collected from twin pairs. Although the genetic factor model is often used to explain a phenotypic behavior measured by a single indicator variable, the effect of genetic and environmental factors on phenotypic behaviors measured by multiple indicators can be estimated using analogous latent variables in a multivariate genetic factor model (Heath et al. 1989b; Neale and Cardon 1992).

Although applications of the genetic factor model have primarily been focused on the decomposition of individual differences in terms of covariance structures, the mean structures of phenotypic indicators can also be modeled by genetic and environmental factors. Dolan (1989) proposed a model for the genetic factor analysis with mean structures based on the adjoined sum of squares and cross products (SSCP) matrix in which the intercepts of phenotypic indicators are set to zero and factor means are estimated. Although this model can estimate the means of genetic and environmental factors, setting intercepts of all indicator variables to zero ignores intercept differences between variables. The assumption of identical zero intercepts is not necessarily appropriate in many situations (Dolan et al. 1992). It is more reasonable to believe that the intercept of each indicator is different across indicator variables or that measurement artifacts may produce baseline differences in indicator variables not due to the factors in the model. For this reason, models which include manifest variables intercepts in addition to factor means have been appealing.

Unfortunately, models with both estimated intercepts and factor means are not mathematically identified without further restrictions in single-group analyses (Dolan et al. 1992). In multiple-group settings, however, relative differences of factor means and variances across groups can be estimated. Under multiple-group settings, factor means and variances in a selected reference group are fixed to zero and one, respectively, and factor means and variances in non-reference groups can be estimated as departures from those of a reference group, given that factor loadings and intercepts are assumed invariant across groups (Sörbom 1974). Dolan et al. (1992) applied this method to a genetic factor model to decompose factor mean differences between groups into genetic and environmental factors, in which zygosity groups are further divided by additional grouping variables, such as sex or ethnicity. In this model, factor means in the non-reference groups are estimated as differences relative to the factor means in the reference groups in which factor means are set to zero. Thus, the mean of each factor indicator in non-reference groups is determined by its intercept and the differences from the reference groups due to each factor, while the mean of each indicator variable in the reference groups is determined by its intercept alone. This model enables estimation of the direction and extent of the changes in means of phenotypic behavior between groups due to genetic and environmental factors without assuming zero intercepts of phenotypic indicators.

The model proposed by Dolan et al. (1992) has been employed in subsequent studies (Dolan and Molenaar 1994; Rowe and Cleveland 1996; Rowe and Rodgers 1997; Cleveland et al. 2000; Heiman et al. 2003) to determine the origins of within and between group variations on phenotypic behaviors due to genetic and environmental components. However, the model has yet to be applied to phenotypic behaviors measured by ordered categorical indicator variables. This is surprising, given that many psychological measurements used in behavior genetics involve categorical variables with relatively few ordered response categories (e.g., Likert scales or attitude scales). Direct applications of the traditional genetic factor model to ordered categorical variables, in which ordered categorical variables are treated as continuous variables, can often be misleading because the assumptions of factor analytic models are not met (Bollen 1989). This problem has been dealt with by assuming that the observed categorical variables are categorizations of normally distributed latent continuous variables which underlie observed categorical variables.

Applications of genetic factor models based on underlying latent continuous variables have been attempted using polychoric correlation matrices as input data (Loehlin 1993; Truett et al. 1992). However, using a polychoric correlation matrix is equivalent to analyzing standardized variables and the decomposition of latent means is not possible because no factor means can be estimated. Analyses of ordered categorical variables via underlying continuous variables were generalized under the framework of the Latent Response Variable (LRV) formulation (Christoffersson 1975; Muthén 1984; Muthén and Asparouhov 2002; Skrondal and Rabe-Hesketh 2004). The LRV formulation is an extension of the general idea of polychoric correlations in that it relates the observed categories of responses to an underlying continuous variable. The LRV formulation, however, more generally extends factor analytic and structural models to ordered categorical variables by relating the latent response variables to observed categorical variables using thresholds given distributional assumptions on latent response variables. Prescott (2004) described genetic factor analyses of ordered categorical variables using LRV formulation in Mplus (Muthén and Muthén 2007). Although Prescott (2004) described several types of possible genetic factor analyses with continuous and categorical variables in single-and multiple-group settings, the decomposition of group differences of phenotypic means into genetic and environmental factors, as in Dolan et al. (1992), has not been applied to the case of ordered categorical variables.

In this paper, a multiple-group genetic factor model is proposed for decomposition of mean differences of a phenotypic behavior between groups when the indicator variables under consideration are ordered categorical. In contrast to limitations inherent in analysis of the polychoric correlation matrix, the LRV formulation allows estimation of distributional differences of latent response variables using equality constraints on thresholds across groups. Analyses of ordered categorical variable in multiple-group settings have been described elsewhere (Muthén and Christoffersson 1981; Muthén and Lehman 1985; Muthén 1989; Muthén and Asparouhov 2002; Millsap and Yun-Tein 2004). However, decomposition of phenotypic means within the genetic factor model requires additional model specification and identification considerations beyond traditional multiple-group structural models due to the rationale underlying the specification of genetic and environmental effects in genetic factor models. Specifically, under the genetic factor model, differential covariance structures due to genetic and environmental factors are identified across groups defined on the basis of the zygosities of twin pairs. In multiple-group settings using the genetic factor model, these zygosity groups are often further divided based on additional grouping variables such as sex or ethnicity. The standard approach in multiple-group analyses is to select a group as a reference group, in which some parameters are fixed to constants to determine scale of measurement of the factors with these respective parameters are freely estimated. Under the multiple-group genetic factor model, by contrast, reference and non-reference groups are determined based on the additional grouping variable(s). All zygosity groups within a selected level of additional grouping variables are set as the reference groups, with relevant parameters fixed to constants and with the corresponding parameters estimated in the remaining non-reference groups subject to equality constraints across zygosity groups in the same level of the grouping variable. In order to avoid confusion in the presentation which follows, “group” refers to the group divided by additional grouping variables and “zygosity group” refers to grouping of twin pairs based on zygosity.

In addition, identification of factor analytic models with ordered categorical variables is more complicated than for factor models with continuous variables, in that latent response variables are indirectly modeled via distributional assumptions on latent response variables and thresholds. Thus, identification of means and variances of both factors and latent response variables should be considered. Millsap and Yun-Tein (2004) derived general conditions of identification that can be applied to various forms of factor analytic models but, as they pointed out, the identification conditions of a specific model should be developed considering its structure and the hypotheses to be tested. Specification of such models for the multiple-group genetic factor model with factor means based on ordered categorical manifest variables has not been developed.

This paper begins with a brief presentation of the genetic factor model for phenotypic means proposed by Dolan et al. (1992) followed by a description of the application of LRV formulation for decomposing mean differences of latent response variables associated with phenotypic behaviors measured by ordered categorical variables into genetic and environmental factors. Model specification and identification are derived within this context, along with related discussions of intercept differences of variables, as pointed out by Dolan et al. (1992), and factorial invariance within the context of the proposed model. As an example of the approach, the model is used to explore sex differences in genetic and environmental factors in items taken from the conservatism scale (Wilson and Patterson 1968) in data from the Australian Twin Registry using Mplus (Muthén and Muthén 2007).

The Model

The genetic factor model for phenotypic means

The genetic factor model (Neale and Cardon 1992) is an application of the multiple-group factor model used to identify the relative contributions of genetic and environmental factors on individual differences in phenotypic behavior based on covariance matrices of genetically informative data collected from twin pairs. When multiple phenotypic indicators for a phenotypic behavior are available, variances of each observed variable are represented as a linear function of genetic and environmental factors and a residual variance term unique to each indicator variable. This model is called the Independent Pathway model or Biometric model, because each indicator variable has a distinct factor loading from each factor (Neale and Cardon 1992). Another way of modeling phenotypic behaviors measured by multiple indicators is the Common Pathway model or Psychometric model in which genetic and environmental factors are assumed to have factor loadings on a single latent variable extracted from multiple indicators. For reasons described below, the present paper discusses the LRV formulation for the biometric model rather than the common pathway model due to identification difficulties associated with the latter.

In multiple-group genetic factor models, in which zygosity groups are further divided based on additional grouping variables, mean difference of each indicator variable across the groups due to each genetic and environmental factors can be estimated (Dolan et al. 1992). This model can be represented in matrix form as:

| (1) |

where y1j(g) and y2j(g) represent the observed variable j from i-th twin (i ={1, 2}) from group g, which is defined by the levels of additional grouping variables. Ai(g), Ci(g), and Ei(g) represent the additive genetic factor, the common environmental factor shared by both twins in the same family, and the unique environmental factor, respectively, for the i-th twin. αj(g) is the intercept of variable yij(g) and εij(g) is the residual of each variable which is not explained by the genetic and environmental factors. Differential structures in the correlation matrix of genetic and environmental factors are assumed across zygosity groups. Specifically:

| (2) |

In Equation 2 the correlation between A1 and A2, r, is set to 1 for monozygotic (MZ) twin pairs and 0.5 for dizygotic (DZ) twin pairs.

The model in Equation 1 is not identified because factor means and intercepts of indicator variables cannot be estimated simultaneously without further constraints. However, in multiple-group settings, as Sörbom (1974) discussed, factor mean differences between groups can be estimated relative to a selected reference group in which factor means and variances are set to zero and one, respectively, provided that the intercept and factor loading of each respective manifest variable are invariant across groups. Dolan et al. (1992) applied this method to decompose phenotypic mean differences between groups in terms of genetic and environmental factors. Specifically, zygosity groups are further divided by an additional grouping variable and all zygosity groups within one level of the grouping variable are set as the reference groups. Factor means and variances are estimated in the remaining groups which share the same level of the grouping variable but are constrained to equality within level of the grouping variable. Given that factor loadings and intercepts are invariant across the reference and non-reference groups, factor means and variances in the non-reference groups are interpreted relative to the latent variable metric observed in the reference groups. Under this model, the mean of variable j is determined as

where δ(n)'s are the factor mean differences from the reference groups. Therefore the mean of each variable in non-reference groups is determined by the intercept and change in the mean from reference groups due to each factor, while the mean of each variable in the reference groups is determined solely by its intercept. The variance/covariance structure between twins is determined as

where ϕ(n)'s are the variances of factors in the non-reference groups, θ represents the residual variance of each variable, and r is the correlation between additive genetic factors for twin 1 and 2, from Equation 2. This model requires multiple indicator variables and, as mentioned above, the independent pathway model. Because there are three common factors for each twin at least three phenotypic means are needed to identify factor means. If the common pathway model is used, the model with factor means estimated in non-reference groups cannot be identified because three factor means in non-reference groups cannot be estimated based on a single latent variable. For this reason, the common pathway model cannot be employed for the purpose of current study.

Application to Ordered Categorical Variables

As mentioned above, direct application of the factor analytic model to ordered categorical variables, in which ordered categorical variables are treated as continuous variables, is often problematic, especially when relatively few response categories are used (Olsson 1979; Johnson and Creech 1983; Lubke and Muthén 2004), due to violations of assumptions of factor analytic models of continuous variables (Bollen 1989). In the LRV formulation, a normally distributed latent response variable, which underlies each observed categorical variable, is assumed and factor models are applied to latent response variables, instead of the observed categorical variables (Muthén 1984; Muthén and Asparouhov 2002; Skrondal and Rabe-Hesketh 2004). Under the LRV formulation, Equation 1 is expressed in terms of the latent response variables. Denoting yij* as continuous latent response variables that underlie observed variable yij for i-th twin (i ={1, 2}), with Cj response categories, the Equation 1 then becomes:

| (3) |

where αj*(g) and εij*(g) are the intercept and residual variance, respectively, of latent responsevariable yij*. From Equation 3 the mean of the latent response variable yij* is determined by its intercept and the means of common factors. The variance/covariance matrix between twins is determined by factor loadings and factor variances/covariances. A latent response variable yj* maps onto observed categorical variable yj with Cj – 1 thresholds.

| (4) |

τj1, τj2...,τjcj–1 are the thresholds which segment the latent response variable yj* into Cj categories. From Equations 3 and 4, the conditional probability that variable yj falls into category c, given the intercept and genetic and environmental factors, is determined as the cumulative probability associated with the (c – 1)-th category subtracted from cumulative probability of the c-th category. Assuming ε*ij is normally distributed with mean of zero and variance of θij, given factors Ai, Ci, and Ei and intercept αj, the probability that variable yij falls into category c is,

| (5) |

where Φ is the cumulative distribution function of standard normal distribution and κ's are the factor means.

The LRV formulation introduces additional parameters (i.e., thresholds). Thresholds are estimated from the marginal distribution of each latent response variable yj*. In single-group analyses yj* is usually assumed to follow a standard normal distribution and thresholds are estimated as z-scores corresponding to the cumulative proportion associated with each response category, which is a consistent estimator of the cumulative probability of the latent response variable. However, latent response variables assumed to have standard normal distributions cannot be used for genetic factor models that decompose means of latent response variables because no information is present regarding mean differences of latent response variables between groups. In multiple-group settings, the distributions of latent response variables do not necessarily have means of zero and unit variances across all groups. By setting the distributions of latent response variables in the reference groups to have mean of zero and unit variance, means and variances of latent response variables for the non-reference groups can be estimated relative to the metric of latent response variables in the reference groups. Minimally, to estimate the mean and variance of each latent response variable in the non-reference groups, two thresholds per each variable need to be constrained equal across groups in order to provide the location and scale of the latent response variable in the non-reference groups. Denoting zj1(n) and zj2(n) as the z-scores corresponding to the cumulative proportions of the first and second categories of variable yj(n) in the non-reference groups and τj1 and τj2 as the thresholds estimated from the reference groups, based on standard normal distribution, μj*(n) and σj*(n), the mean and variance of yj(n), can be estimated from following.

| (6) |

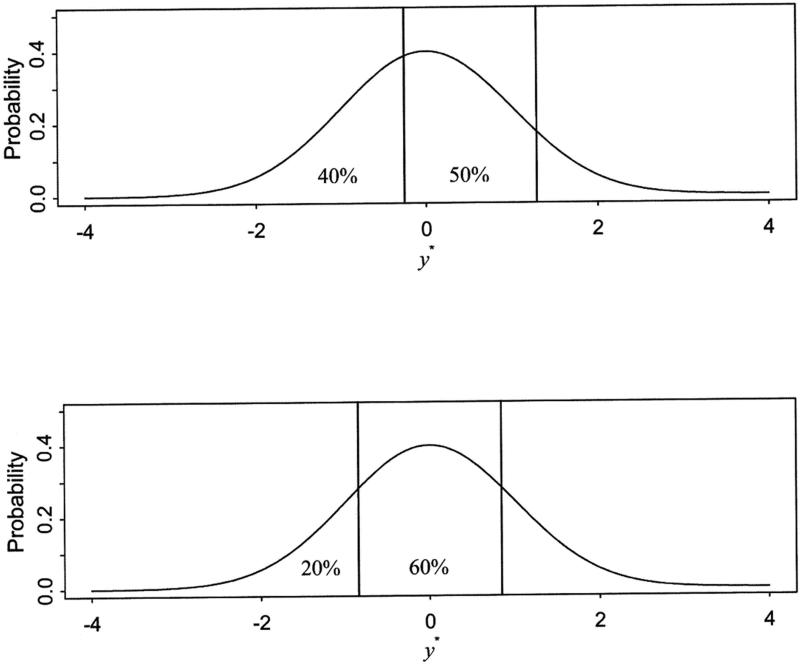

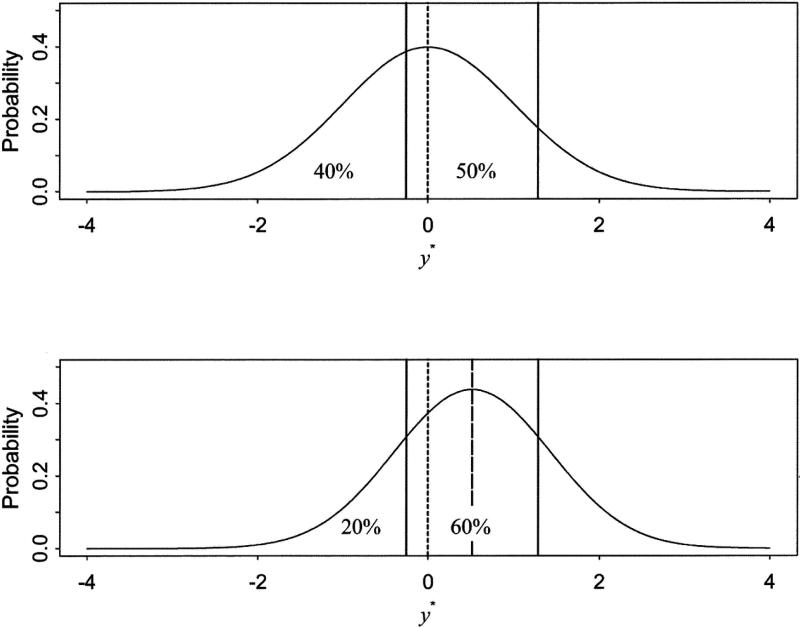

Figures 1 and 2 illustrate estimation of means and variances of a latent response variable across groups. Assuming three response categories, the upper panel of Figure 1 shows the thresholds based on a standard normal distribution for the variable with cumulative proportions of 40% and 90%. Thresholds are estimated as z-scores corresponding to these cumulative proportions and are –0.2533 and 1.2816, respectively. The lower panel shows thresholds for the cumulative proportion of 20% and 80%. With the same distributional assumption on the latent response variable, the first and second thresholds are changed to –0.8416 and 0.8416, respectively. In Figure 2, using the same cumulative proportions as in Figure 1, thresholds are fixed at values from the upper panel and the mean and variance of the latent response variable in the lower panel are estimated by Equation 6. The upper panel is based on standard normal distribution so that the mean is zero (as indicated by a dashed reference line) and the variance is 1. In the lower panel of Figure 2, for the cumulative proportions of 20% and 80%, mean and variance are estimated based on the fixed thresholds and the distribution in the lower panel is changed to have the mean of 0.5141 (marked by a heavy dashed line) and the variance of 0.9119. In short, locational differences of thresholds provide information on the mean differences and the interval between thresholds provides information on the variance differences of latent response variables. Obtained means and variances of the latent response variables can thus be modeled. In general multiple-group analysis of ordered categorical variables, differences in means and variances of a latent response variable across the groups are estimated by constraining respective thresholds to be equal across a selected reference group and remaining non-reference groups (Muthén and Asparouhov 2002; Millsap and Yun-Tein 2004). In multiple-group genetic factor analyses, the reference and non-reference groups are defined by the levels of additional grouping variables. All zygosity groups within the selected level of the grouping variable are set as the reference groups with appropriate equality constraints applied across the reference and non-reference groups.

Figure 1.

Different thresholds estimated for different response proportions based on the standard normal distributions. In the upper panel, thresholds estimated for the cumulative proportions of 40% and 90% are -0.2533 and 1.2816 (vertical lines in the upper panel), respectively. In the lower panel, thresholds estimated for the cumulative proportions of 20% and 80% are -0.8416 and 0.8416 (vertical lines in the lower panel), respectively.

Figure 2.

Different means and variances estimated based on the fixed thresholds. In the upper panel, thresholds estimated for the cumulative proportions of 40% and 90% are -0.2533 and 1.2816 (vertical lines in the upper panel), respectively. In the upper panel, mean and variance are zero (dashed line in the upper panel) and one, respectively. In the lower panel, for the cumulative proportions of 20% and 80%, thresholds are fixed to the same values from the first panel (vertical lines in the lower panel) and mean and variance are estimated as in Equation 5 based on the fixed thresholds, which are 0.5141 (heavy dashed line in the lower panel) and 0.9119, respectively.

Even though the means and variances of latent response variables can be estimated as departures relative to the reference groups, this model is still under-identified. The identification of the model is further complicated because the latent response variables are indirectly modeled based on distributional assumptions and thresholds. The model in Equation 3 can be identified, however, by applying constraints on parameters. Millsap and Yun-Tein (2004) developed the general minimum conditions to identify multiple-group factor models of ordered categorical manifest variables. Although these minimal identification conditions cover factor analytic models generally, the unique structure and requirements of the genetic factor analysis require additional consideration when developing identification constraints.

It can be shown that the following set of constraints can minimally identify the model in Equation 3: (a) the mean and variance of each latent response variable, yj*, are set to zero and one, respectively, in the reference groups, (b) the mean and variance of each factor are set to zero and one, respectively, in the reference groups, (c) factor loadings are constrained to be equal across groups, (d) the intercept for each variable is set to zero for both reference and non-reference groups, and (e) for three selected indicator variables two thresholds are set to be equal across groups. Constraints (a) and (b) identify all parameters in the reference groups by providing the scale for latent response variables and factors. Constraint (c) identifies the factor loadings for the non-reference groups. Constraint (e) identifies the means and variances of the latent response variables of the three chosen indicator variables in the non-reference groups, which, in conjunction with the constraints (c) and (d), leads to the identification of the distributions of the factors in the non-reference groups. The means and variances of the latent response variables not included in constraint (e) can be estimated based on the distributions of the factor and factor loadings. Identification of the model is detailed in Technical supplement A. Thus, the covariance structures are determined as follows

where ϕ(n)`s are the variances of factors. Means of each latent response variable are determined as,

| (7) |

where δ(n)'s are the differences of factor means from the reference groups.

Several related issues of the proposed model require further elaboration. First, intercept differences between variables are not included in the current model. As noted by Dolan et al. (1992), setting intercepts of the variables to zero is equivalent to assuming that all indicator variables have same intercepts, which ignores possible location differences among the variables. However, in the LRV formulation, intercepts and thresholds are not entirely distinct from each other and intercept differences between the latent response variables are absorbed into the differently estimated thresholds across variables (Muthén and Asparouhov 2002; Millsap and Yun-Tein 2004). To show this point, Equation 5 is revisited.

| (8) |

Differences of intercepts and thresholds cannot be simultaneously estimated. It requires either intercepts of variables fixed to a constant or one of the thresholds set equal across variables to estimate thresholds or intercept differences. Assuming that the variables have the same number of categories, estimating the intercept difference between variables requires that at least one threshold is set equal across the variables, to provide a reference point from which intercept differences can be estimated, and one intercept of a selected variable is fixed to a constant, usually zero. With the intercept differencesin the model and a constrained c-th threshold, the conditional probability that the response yj is less than or equal to c-th category, given intercept and factors, is,

| (9) |

The subscript j is omitted from τc because c-th threshold of each variable has been set equal across variables. From Equation 9 the threshold for the c-th category of variable j is adjusted from τc by αj, which is (τc – αj). Thus, if any intercept difference exists between variables, it is captured by differentially estimated thresholds across variables. A common threshold adjusted for variable j, (τc – αj), from Equation 9, and the threshold estimated for variable j, τcj, from Equation 8 should be equivalent. Also, the numbers of estimated intercept and threshold parameters are the same in Equations 8 and 9. Supposing p variables with C categories each, Equation 8 contains p(C – 1) estimated thresholds. In Equation 9, parameters to be estimated are a threshold, τc; constrained across variables; p(C – 2) remaining thresholds; and (p – 1) intercepts making a total of p(C – 1) estimated parameters. Thus, Equations 8 and 9 are re-parameterizations of each other and, given that the different intercept is not a main substantive question, estimating the differential intercept across the variables is unnecessary. Differences of intercepts across variables are therefore absorbed into different estimates of thresholds across the variables. Likewise, intercept differences of a subset of variables across groups are also captured by differently estimated thresholds. In the identification constraints described above, two thresholds per each of three selected indicator variables are constrained to be equal across groups. Thus the rest of the thresholds can be differently estimated across groups and the intercept differences of those variables across groups are absorbed into group specific thresholds for each indicator variable.

Second, although, in the minimal constraints described above, differences of factor means and variances across groups can be estimated based on the invariance of factor loadings and thresholds of a subset of parameters, the invariance of the remaining parameters not constrained can further be investigated as part of a larger examination of factorial invariance across groups. Testing invariance hypotheses in factor models using ordered categorical variables is more complicated than in the cases of continuous variables because the latent response variables are indirectly modeled using distributional assumptions and thresholds. As such, factorial invariance involves interrelated equalities of factor loadings, intercepts, residual variances, and thresholds of latent response variables across groups. Testing invariance hypotheses using LRV's within the proposed model is more complicated because constraints in the minimally identified model require factor loadings to be constrained to equality in order to estimate the means and variances of the latent response variables and the genetic and environmental factors. Further, the location of the LRV must be determined as a function of factor means in those variables chosen for the minimal identification constraints.

Nevertheless, there is some flexibility when investigating invariance hypotheses relative to a base model with minimal identification constraints. This model can then be compared to a model in which these thresholds are set equal across groups. Under the LRV approach, as seen above (see Equation 6 and Figures 1 and 2), thresholds play important roles because they contain information about means and variances of latent response variables. By comparing the fit of a model with fully invariant thresholds and loadings to the fit of the minimally constrained model, one can at least test whether a model with fully invariant thresholds and loadings is a parsimonious, well-fitting alternative. If it fits appreciably worse than the minimally constrained model, either factor loadings or thresholds may not be invariant. Although the specific source of misfit of the model may be difficult to pinpoint, general strategies for probing the possible sources of model misfit in the discussion section below.

Finally, factorial invariance of ordered categorical variables also involves the invariance of the residual variance of the latent response variable associated with each indicator variable. The invariance of residual variances can also be tested by fitting the model with equality constraints on residual variances. However, it should be noted that, depending on the parameterization method used, residual variances of latent response variables may not be independent parameters to be estimated (Muthén and Asparouhov 2002) and, thus, applying constraints on residual variances may not be possible. Note also that no genetic factor structure is specified at the level of each indicator variable in Equation 3. It is possible to incorporate additional genetic and environmental factor structures specific for each variable (as was done for the original genetic factor model described by Heath et al. 1989a for continuous variables) without modifying current identification constraints. However, given the computational burden introduced by including genetic and environmental components unique to each variable, sample size considerations, and the fact that such effects are often not of substantive interest, allowing residual covariance between twins which vary across zygosity groups appears a reasonable accommodation of the unique genetic and environmental factors associated with individual indicator variables.

Illustrative Example

Data collected from the Australian Twin Registry on Wilson-Patterson conservatism scale (Wilson and Patterson 1968) were used as an example application of the proposed model (see Martin et al. 1986 for more information on data collection and summary statistics). Based on zygosity and sex, 3,808 pairs of twins were divided into five groups. There are 1202 pairs of monozygotic female (MZF) twins, 567 pairs of monozygotic male (MZM) twins, 747 pairs of dizygotic female (DZF) twins, 350 pairs of dizygotic male twins (DZM), and 912 pairs of opposite sex (DZO) twins. The Wilson-Patterson conservatism scale consists of 50 items with three response categories per each item that indicate the degree of assent: “Yes”, “?”, and “No”. Response categories are assumed to be ordered because they reflect the degree of a respondent's supportive attitude on each item. As originally developed, odd-numbered items were worded to have positive relationships with conservative attitude (e.g. Apartheid, Church Authority, etc.) and even-numbered items were worded to have negative relationships (e.g. Colored Immigration, Evolution Theory, etc.) (Wilson and Patterson 1968).

Because analyzing all 50 items in one model poses great computational burdens on parameter estimation of the model being considered, items were first factor analyzed to determine general sub-dimensions of conservative attitude and each subset of items was separately analyzed. This practice is also in keeping with the original design of the scale, which assumes that an individual can have different attitudes on different sub-dimensions of conservatism (Wilson and Patterson 1968). An exploratory factor analysis performed in Mplus version 5 (Muthén and Muthén 2007) using promax rotation produced four oblique sub-dimensions. Each sub-dimension was named according to the items included: the political, religious, racial, and social dimensions. Within each factor, items with factor loadings with an absolute value greater than 0.4 were retained, and are shown in Table 1. The pattern of items included in each dimension is roughly consistent with earlier exploratory factor analyses of the data (Truett et al. 1992; Eaves et al. 1999).

Table 1.

Items Included in Each Dimension

| Political | Patriotism, Licensing Law, Royalty, Censorship, Strict Rules, Inborn Conscience |

| Religious | Evolution Theory, Sabbath Observance, Birth Control, Divine Law, Legalized Abortion, Church Authority, Divorce |

| Racial | Death Penalty, Empire Building, Women Judges, Apartheid, Caning, Colored Immigration |

| Social | Hippies, Modern Art, Student Pranks, Nudist Camps, Jazz, Casual Living, Pyjama Party |

Age was included in the model as a covariate because of the age-cohort effect on conservatism (Truett 1993; Eaves et al. 1999). Truett (1993) found strong evidence that conservatism scores on this scale are greater in older respondents than in younger respondents after adjusting for a variety of other covariates and found that this change is more rapid after the fifth decade of life. In this sample, such a rapid change after the fifth decade of life was not found and, thus, the linear effect of the deviation score from the mean of age was used as a covariate. The regression coefficient of age on each variable was constrained to be equal across groups.

Model Specification

In matrix form, for the variable j, the model is expressed as

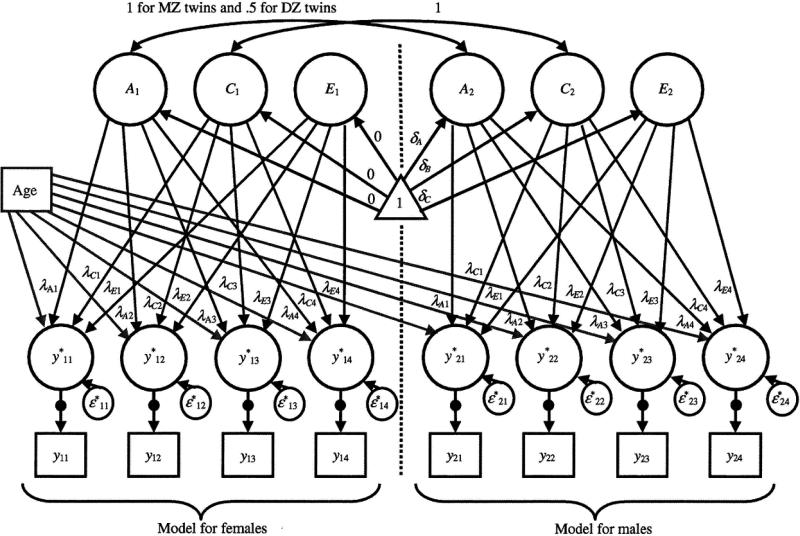

where βj is the regression slope for variable j on age. Since all observed variables have three ordered categories, the latent response variable yj*(g) in group g is mapped onto the observed variable yj(g) with two thresholds, τj1(g) and τj2(g). In order to set female groups as reference groups, the MZF, DZF and female twins of DZO group were set as the reference groups, and MZM, DZM, and the male twins of DZO group were set as the non-reference groups. The path diagram in Figure 3 illustrates this model with four indicator variables. To present the models for both female and male groups in one diagram, the left side of diagram is the model for female groups and the right side is the model for male groups. The triangle in the diagram denotes a column vector of ones and, as such, the loadings originating from this variable to factors represent factor means. Note that factor means in the female part are set to zero, but are estimated in the male part of the diagram. Latent response variables are represented as circles linked to observed categorical variables via filled circles to represent the transformation from latent response variables to observed categorical variables.

Figure 3.

The path-diagram of the proposed model. The left side of diagram is the model for females and the right side is the model for males. The loadings originating from the triangle to factors represent the factor means. Latent response variables are represented as circles linked to observed categorical variables via filled circles.

Mplus version 5 (Muthén and Muthén 2007) was used to estimate the model parameters. The default estimation method for ordered categorical variables in Mplus, weighted least squares (WLSMV), was used (Muthén and Muthén 2007). The variance of each variable in non-reference groups was estimated via scale parameters using the Delta Parameterization method (Muthén and Asparouhov 2002). The scale parameter is the inverse of the standard deviation of the marginal distribution of the latent response variable for each categorical indicator variable. Thus, the scale parameter for each variable was estimated in the non-reference groups and fixed to one in the reference groups. Although the delta parameterization has computational advantages over the theta parameterization (Muthén and Asparouhov 2002), which is an alternative parameterization in Mplus, each residual variance is not a free parameter to be estimated and no equality constraints across the groups on residual variances are permitted withthe delta parameterization. The residual variances are computed as in reference groups and as in non-reference groups. Inability of imposing equality constraints on residual variances with the delta parameterization prevents the assessment of the invariance of residual variances. Equality constraints on residual variances can be applied with the theta parameterization, but the models using the theta parameterization for these data did not converge in any sub-dimensions.

The model was specified in accordance with the minimal identification constraints described in previous sections. Variances of latent response variables in MZF, DZF, and the female part of DZO groups were set to one by setting the scale parameters for each variable to one. The scale parameters in MZM, DZM, and male part of DZO groups were estimated. Factor means and variances were set to zero and one, respectively, in female groups, and were estimated in male groups. Setting factor means to zero in female groups sets the means of latent response variables to zero because Mplus does not allow intercepts for ordered categorical variables and the intercepts are set to zero by default. Factor loadings were set to be equal across groups. The thresholds of the first three indicator variables were set to be equal across female and male groups. As in other genetic factor analyses, the model is symmetric and respective parameters are constrained to be equal across twins in the same pair. The covariance structure between twins was specified by With statements in Mplus, but With statements does not permit direct specification of correlations between non-standardized variables. Instead, to apply the correlation structure in Equation 2, nonlinear constraints were applied to covariances between factors using Model constraint statements. Covariances between common environmental factors (factor C) were constrained to be equal to the variance of factor C in MZM and DZM groups and the square root of the variance of factor C estimated for male part in DZO group. Covariances between additive genetic factors (factor A) were constrained equal to the variance of additive genetic factor in MZM group; as half of the variance of factor A in DZM group; and as half of the square root of the variance of factor A estimated for the male part in DZO group. Instead of modeling genetic factor structure for each variable, the covariance between twins for each variable was estimated. The residual covariances between twins were allowed to vary across zygosity groups (MZF and MZM for monozygotic twins and DZF, DZM, and DZO groups for dizygotic twins) to accommodate different correlation structures between monozygotic and dizygotic twins. An example Mplus program is in Table 7 with detailed description in Technical supplement B.

Analysis

Models with minimal identification constraints were fit first for all sub-dimensions. Even though χ2 values were significant, which might be due to the large sample size, other fit indices indicated acceptable fit for all sub-dimensions (χ2 (218) = 258.709, CFI = 0.989, TLI = 0.987, RMSEA = 0.016 for the political dimension; χ2 (190) = 274.355, CFI = 0.993, TLI = 0.993, RMSEA = 0.024 for the religious dimension; χ2 (201) = 294.627, CFI = 0.981, TLI = 0.977, RMSEA = 0.025 for the racial dimension; χ2 (241) = 411.206, CFI = 0.982, TLI = 0.980, RMSEA = 0.030 for the social dimension). Models with fully invariant thresholds were then fit and compared with the minimally constrained models. Since χ2 values from weighted least square estimation (WLSMV) are not valid for χ2 difference testing (Muthén and Muthén 2007), the difftest option in Mplus was used. For the political dimension and religious dimension, χ2 differences between the models with fully invariant thresholds and minimally constrained models were not significant (χ2 diff (5) = 1.166, P = 0.948 for the political dimension and χ2 diff (6) = 7.628, P = 0.267 for the religious dimension), while χ2 differences were significant for the racial dimension and social dimension (χ2 diff (5)= 17.714, P = 0.003 and χ2 diff (5)= 19.813, P = 0.002, respectively). As discussed above, worse fit of models with fully invariant thresholds than the minimally constrained model may indicate lack of factorial invariance between groups for those sub-dimensions and further investigations to locate the origin of factorial invariance is appropriate. However, because assessing the factorial invariance is not a major purpose of this illustration, it is not described here.

Tables 2, 3, 4, 5 show the parameters estimated from the model for each sub-dimension. Models with fully invariant thresholds for the political dimension (Table 2) and the religious dimension (Table 3) are shown in accordance with the results of χ2 difference tests of the model with fully invariant thresholds. The models for the racial dimension (Table 4) and the social dimension (Table 5) are the models with minimal identification constraints. The square of the factor loading associated with each factor represents the proportion of the variance in each latent response variable explained by each factor in female groups, but same interpretation is not valid for male groups because variances of factors and latent response variables are not set to one in male groups. Thus, the R2's for each item due to each factor for female and male groups are shown to the right of the factor loadings to show the relative contribution of each factor to the variance of each latent response variable. Signs of factor loadings inform the direction of the factors on the each item. As mentioned in the previous section, odd-numbered items were positively worded and even-numbered items were negatively worded for conservative attitudes. Therefore factor loadings on positively worded item and negatively worded item are expected to have opposite signs, but, for some factors, this pattern was not clearly presented. Factor means are estimated means for the male groups relative to the factor means of female groups in which factor means were set to zero. Estimated means quantify the magnitude and direction of differences in factor means of male groups relative to females. A factor mean multiplied by its factor loading on each item represents the mean difference of the latent response variable between female and male groups due to each factor (see Equation 7). Estimated means of each item for the male groups are shown in Table 6. Item means are computed as linear combinations of factor means as in Equation 7. For ease of presentation, the signs of mean scores of the negatively worded items are reversed in Table 6, so that higher scores represent more conservative attitudes for all items. Factor variances in Tables 2, 3, 4, 5 represent the variances of factors in male groups relative to the factor variances of female groups, in which factor variances were set to one.

Table 2.

Parameter Estimates for the Political Dimension*

| Item | Additive Genetic |

Common Environment |

Unique Environment |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loading (SE) | R2 for female and male | Loading (SE) | R2 for female and male | Loading (SE) | R2 for female and male | |

| Patriotism | 0.632 (0.041) | 0.399 0.381 |

0.253 (0.077) | 0.064 0.030 |

0.103 (0.033) | 0.010 0.013 |

| Royalty | 0.422 (0.029) | 0.178 0.147 |

-0.086 (0.058) | 0.007 0.003 |

0.215 (0.030) | 0.046 0.049 |

| Censorship | 0.396 (0.035) | 0.157 0.143 |

-0.148 (0.054) | 0.022 0.010 |

0.503 (0.041) | 0.253 0.294 |

| Strict Rules | 0.367 (0.061) | 0.135 0.156 |

-0.466 (0.047) | 0.217 0.123 |

0.212 (0.030) | 0.045 0.066 |

| Licensing Laws | 0.219 (0.030) | 0.048 0.073 |

0.031 (0.039) | 0.001 0.001 |

0.383 (0.036) | 0.147 0.284 |

| Inborn Conscience | 0.297 (0.030) | 0.088 0.066 |

0.156 (0.045) | 0.024 0.001 |

0.111 (0.029) | 0.012 0.012 |

| 95% CI | 95% CI | 95% CI | ||||

| Factor Mean** (SE) | 0.231 (0.163) | -0.129 0.590 |

-0.067 (0.167) | -0.395 0.260 |

-1.431 (0.236) | -1.894 -0.968 |

| Factor Variance*** (SE) | 0.934 (0.148) | 0.644 1.225 |

0.457 (0.115) | 0.232 0.682 |

1.190 (0.239) | 0.720 1.190 |

| Fit Statistics | χ2 (219) = 264.465, CFI=0.988, TLI = 0.985, RMSEA = 0.017 | |||||

For the political dimension, parameter estimates are from the model with fully invariant thresholds.

Factor means are estimated in male groups and are set to zero in female groups.

Factor variances are estimated in male groups and are set to one in female groups.

Table 3.

Parameter Estimates for the Religious Dimension*

| Item | Additive Genetic |

Common Environment |

Unique Environment |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loading (SE) | R2 for female and male | Loading (SE) | R2 for female and male | Loading (SE) | R2 for female and male | |

| Legalized Abortion | 0.739 (0.041) | 0.546 0.515 |

0.389 (0.061) | 0.152 0.147 |

0.195 (0.032) | 0.038 0.041 |

| Birth Control | 0.684 (0.038) | 0.468 0.384 |

0.252 (0.064) | 0.064 0.053 |

0.114 (0.040) | 0.013 0.012 |

| Divorce | 0.571 (0.037) | 0.326 0.298 |

0.332 (0.049) | 0.110 0.103 |

0.180 (0.029) | 0.032 0.034 |

| Evolution Theory | 0.266 (0.042) | 0.071 0.073 |

0.389 (0.031) | 0.151 0.160 |

0.164 (0.023) | 0.027 0.032 |

| Sabbath Observance | -0.159 (0.056) | 0.025 0.025 |

-0.498 (0.025) | 0.248 0.251 |

-0.451 (0.023) | 0.203 0.232 |

| Divine Law | -0.137 (0.057) | 0.019 0.022 |

-0.518 (0.024) | 0.268 0.316 |

-0.464 (0.023) | 0.215 0.287 |

| Church Authority | -0.203 (0.059) | 0.041 0.040 |

-0.546 (0.027) | 0.298 0.297 |

-0.448 (0.023) | 0.201 0.226 |

| 95% CI | 95% CI | 95% CI | ||||

| Factor Mean** (SE) | -0.647 (0.271) | -1.178 -0.115 |

1.809 (0.719) | 0.400 3.218 |

-1.189 (0.776) | -2.711 0.332 |

| Factor Variance*** (SE) | 1.386 (0.264) | 0.828 1.943 |

1.418 (0.230) | 0.967 1.870 |

1.602 (0.228) | 1.156 2.049 |

| Fit Statistics | χ2 (190) = 274.355, CFI = 0.993, TLI = 0.993, RMSEA = 0.024 | |||||

For the religious dimension, parameter estimates are from the model with fully invariant thresholds.

Factor means are estimated in male groups and are set to zero in female groups.

Factor variances are estimated in male groups and are set to one in female groups.

Table 4.

Parameter Estimates for the Racial Dimension*

| Item | Additive Genetic |

Common Environment |

Unique Environment |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loading (SE) |

R2 for female and male |

Loading (SE) |

R2 for female and male |

Loading (SE) |

R2 for female and male |

|

| Death Penalty | 0.669 (0.051) |

0.447 0.521 |

0.023 (0.025) | 0.001 0.003 |

-0.097 (0.024) |

0.009 0.029 |

| Empire-building | 0.340 (0.045) |

0.115 0.046 |

0.402 (0.045) |

0.162 0.319 |

-0.675 (0.053) |

0.456 0.480 |

| Women Judges | -0.074 (0.041) |

0.005 0.004 |

-0.181 (0.039) |

0.033 0.105 |

0.188 (0.039) |

0.035 0.061 |

| Apartheid | 0.221 (0.037) |

0.049 0.022 |

0.336 (0.037) |

0.113 0.251 |

-0.345 (0.032) |

0.119 0.142 |

| Caning | 0.386 (0.033) |

0.149 0.201 |

-0.014 (0.023) |

0.000 0.001 |

-0.084 (0.022) |

0.007 0.0254 |

| Colored Immigration | -0.349 (0.033) |

0.122 0.073 |

-0.290 (0.034) |

0.084 0.248 |

0.316 (0.030) |

0.010 0.157 |

| 95% CI | 95% CI | 95% CI | ||||

| Factor Mean** (SE) | 0.974 (1.086) |

-1.154 3.102 |

14.262 (11.995) |

-9.248 37.772 |

10.108 (8.028) |

-5.626 25.843 |

| Factor Variance*** (SE) | 1.431 (0.380) |

0.686 2.175 |

7.074 (2.187) |

2.787 11.360 |

3.779 (0.915) |

1.985 5.573 |

| Fit Statistics | χ2(201) = 294.627, CFI = 0.981, TLI = 0.977, RMSEA = 0.025 | |||||

For the racial dimension, parameter estimates are from the model with minimal identification conditions.

Factor means are estimated in male groups and are set to zero in female groups.

Factor variances are estimated in male groups and are set to one in female groups

Table 5.

Parameter Estimates for the Social Dimension*

| Item | Additive Genetic |

Common Environment |

Unique Environment |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loading (SE) |

R2 for female and male |

Loading (SE) |

R2 for female and male |

Loading (SE) |

R2 for female and male |

|

| Hippies | 0.584 (0.021) |

0.341 0.332 |

-0.042 (0.039) |

0.002 0.005 |

0.316 (0.024) |

0.100 0.123 |

| Modern Art | 0.295 (0.026) |

0.087 0.076 |

-0.083 (0.029) |

0.007 0.017 |

0.553 (0.031) |

0.306 0.336 |

| Student Pranks | 0.526 (0.026) |

0.277 0.354 |

-0.160 (0.039) |

0.026 0.094 |

0.051 (0.023) |

0.003 0.004 |

| Nudist Camps | 0.644 (0.031) |

0.415 0.371 |

0.274 (0.053) |

0.075 0.194 |

0.290 (0.025) |

0.084 0.095 |

| Jazz | 0.237 (0.027) |

0.056 0.048 |

-0.042 (0.026) |

0.002 0.004 |

0.487 (0.030) |

0.237 0.256 |

| Casual Living | 0.397 (0.028) |

0.158 0.155 |

0.168 (0.036) |

0.028 0.080 |

0.257 (0.026) |

0.066 0.082 |

| Pyjama Party | 0.427 (0.029) |

0.182 0.171 |

0.194 (0.036) |

0.038 0.102 |

0.298 (0.024) |

0.089 0.105 |

| 95% CI | 95% CI | 95% CI | ||||

| Factor Mean** (SE) | 0.670 (0.219) |

0.240 1.100 |

-0.675 (0.811) |

-2.264 0.915 |

-0.855 (0.189) |

-1.226 -0.484 |

| Factor Variance*** (SE) | 1.357 (0.184) |

0.966 1.717 |

3.914 (0.803) |

2.339 5.488 |

1.716 (0.234) |

1.258 2.174 |

| Fit Statistics | χ2(241) = 411.206, CFI = 0.982, TLI = 0.980, RMSEA = 0.030 | |||||

For the social dimension, parameter estimates are from the model with minimal identification conditions.

Factor means are estimated in male groups and are set to zero in female groups.

Factor variances are estimated in male groups and are set to one in female groups.

Table 6.

Estimated Means of Latent Continuous Variables for Males*

| Political | Mean | Religious | Mean | Racial | Mean | Social | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patriotism | -0.018 | Birth Control | 0.122 | Death Penalty | -0.001 | Hippies | -0.149 |

| Licensing Law | -0.500 | Legalized Abortion | 0.004 | Empire-building | -0.758 | Modern Art | 0.219 |

| Royalty | -0.204 | Divorce | -0.017 | Women Judges | 0.753 | Student Pranks | -0.417 |

| Censorship | -0.618 | Evolution Theory | -0.337 | Apartheid | 1.520 | Nudist Camps | 0.001 |

| Strict Rules | -0.187 | Sabbath Observance | -0.262 | Caning | -0.673 | Jazz | 0.229 |

| Inborn Conscience | -0.101 | Devine Law | -0.297 | Colored Immigration | 1.282 | Casual Living | 0.067 |

| Church Authority | -0.324 | Pyjama Party | 0.010 |

The signs of mean scores of the negatively worded items were reversed, so that higher scores represent more conservative attitudes for all items.

For the political dimension, in Table 2, R2's indicate that the additive genetic factor was an important factor that determined the variance of most items included in this dimension, while environmental factors were only important for some items (“Strict Rules” and “Licensing Laws”). The R2's were not noticeably different between female and male groups with a few exceptions (the common environmental factor on “Strict Rules” and the unique environmental factor on “Licensing Law”). The factor mean of the unique environmental factor was negative and the largest in absolute value while factor means of the additive genetic factor and common environmental factor were not significantly different from zero. The patterns of factor means and loadings resulted in the negative net effect on each item for males (the first column of Table 6). Relative to women, men showed more variance in the unique environmental factor but less variance in the additive genetic and common environmental factors.

For the religious dimension, as shown in Table 3, variances of items related to marriage and procreation were determined relatively more by the additive genetic factor, whereas the variances of items related to religious claims were largely determined by environmental factors. R2's indicate that the contributions of each factor on each latent response variable were not noticeably different between female and male groups. The mean of the common environmental factor for men was positive and the largest in absolute value and the corresponding mean of the additive genetic factor was negative. The mean of the unique environmental factor was negligible. Thus, mean differences between men and women were mainly determined by the common environmental and additive genetic factors, which resulted in the negative net effect on the items related to religious claims and positive net effect on the items related with procreation in men (second column of Table 6). Higher factor variances on the bottom of Table 3 indicate that the factor variances were larger in men.

For the racial dimension, factor loadings and R2's in Table 4 show no dominant factor affecting all items in this dimension. The additive genetic factor was relatively more important in determining the items “Death Penalty” and “Caning”. The relative contributions of factors varied between female and male groups in some items. Factor means were not significant for all three factors, and thus further interpretation of factor means is not necessary. Men appeared much more variable in terms of their environmental factors, as evidenced by the larger factor variances associated with the environmental factors.

For the social dimension, in Table 5, the additive genetic factor was an important factor for explaining the variance of most items while unique environmental factors were important for items “Modern Art” and “Jazz.” No noticeable differences between male and female groups were found for R2 due to each factor. The factor mean was negative and largest in absolute value for the unique environmental factor. The factor mean for the additive genetic factor was positive and the factor mean for unique environmental factor was negative. Thus, the mean differences between men and women were mainly determined by the additive genetic factor and unique environmental factor, which results in the pattern of net effect in Table 6. Factor variances associated with environmental factors were larger in men (shown on the bottom of Table 5).

Discussion

The model proposed in this study incorporates latent mean structures for ordered categorical variables in a genetic factor model using the LRV formulation. Between group differences of means in estimated latent response variables associated with the ordered categorical variables are decomposed into differences due to genetic and environmental factors. A main advantage of the proposed model is its ability to test hypotheses regarding the origins of within and between group variations in phenotypic behaviors due to environmental and genetic factors in ordered categorical variables and to make statements as to whether these effects suppress or elevate levels of a phenotypic behavior. In the case of continuous phenotypic indicators, the genetic factor model with mean structure proposed by Dolan et al. (1992) provides a method in this regard, and the model proposed here extends it to the case of ordered categorical variables. The minimal constraints needed to identify the model with latent mean structures were derived and the models with further constraints on the subset of parameters of interest can fit and compared to the model with minimal constraints to test related hypotheses.

The framework of the proposed model can also be applied to the case of longitudinal panel studies. Analogous to multiple-group settings, one of the occasions of repeated measurements can be set as a reference point. If the same variable is measured repeatedly for the same respondent, one can justifiably assume invariant thresholds across repeated measurements. Proportional differences across repeated measurements can then be converted into distributional differences of the latent response variables based on equally constrained thresholds across repeated measurements (Bollen and Curran 2006; Mehta et al. 2004). If the distributional differences of latent response variables over time are estimated, then the autoregressive effects of genetic and environmental factors on mean differences over time can be estimated (Dolan et al. 1991) or genetic and environmental effects on the latent growth factors, intercept and slope, can be analyzed (McArdle 1986).

Although the model as proposed offers a useful method for decomposing latent differences of ordered categorical variables across groups via genetic and environmental factors, several limitations of the model must be kept in mind when applying and interpreting such model. Most of these limitations derive from the fact that distributional differences of latent response variables are estimated by means of proportional differences of observed categorical variables, and the constraints required to identify the model. First, although the minimum identification constraints derived can provide some flexibility for further constraints on parameters, invariance constraints on required parameters are not avoidable. It is possible to constrain alternative sets of parameter constraints and use of a different set of minimal parameter constraints would result in different estimated parameters. This is a common issue associated with factor models with ordered categorical variables because latent response variables are indirectly modeled by distributional assumption and thresholds and not all parameters can be estimated (Millsap and Yun-Tein 2004). Thus, the purpose and structure of specific models should be considered when identification constraints are chosen. Although the identification constraints derived are appropriate for the purpose and structure of the proposed model, some examination of these assumptions should be explored.

Recall that three variables are required to have two invariant thresholds across groups. Selected three variables function as anchoring variables across groups in order to provide the scales of three factors – additive genetic, common environmental, unique environmental factors. Although, in the example, the first three variables were chosen for the threshold constraints, any set of three variables could have been selected and could lead to different results. Moreover, if the variables have more than three response categories, so that there are more than two thresholds per variable, any of two thresholds can be constrained equal across groups. If the thresholds of one subset of indicator variables are more invariant than of other variables, it is more reasonable to apply the equality constraints on those variables. These questions are not confined to genetic factor analyses and Mehta et al. (2004) suggested a mathematical formulation on the threshold invariance in the context of repeatedly measured ordered categorical variables which can also be applied to multiple-group contexts. However this method only applies to the case of more than two thresholds per variable. Determining which set of variables has invariant thresholds may be analogous to finding anchoring items with invariant item characteristics as described in studies of differential item functioning (DIF) analyses within item response theory (IRT). As such, iterative processes that have been proposed to find such anchoring items (e.g. Candell and Drasgow 1988; Drasgow 1987), and can be utilized in the context of genetic factor analyses to find appropriate combination of the variables to apply equality constraints on thresholds.

As noted earlier, assessment of invariance of factor loadings in the proposed model is somewhat complicated. Factor loadings are set equal across groups in the minimal identification constraints and freeing them across groups to test factor loading invariance would under-identify the model. Thus, testing factor loading invariance therefore requires the use of alternative approaches. One possible solution is to constrain thresholds fully invariant and to free any factor loadings not required to identify the model. This model could be compared to the proposed model, although these models are not nested within each other and such comparison would have to be based on information criteria. Alternatively, group specific factor loadings could be estimated if means and variances of both factors and latent response variables are set to zero and one in all groups. Group specific thresholds can then be estimated. This method may provide an alternative for assessing factor loading invariance because different factor loadings between groups can be estimated across groups while the group differences of means and variances of latent response variables are captured by differently estimated thresholds across groups. Factor loadings can be constrained equal across groups from this model and those two models can be compared to obtain the evidence of factor loading invariance. However, with this setting, mean of each latent response variable is not decomposed into genetic and environmental factors, and adding factor means may produce different patterns of factor loadings. This strategies while heuristic and labor intensive may prove quite useful in future applications.

Additionally, the delta parameterization method of Mplus has been used in example analysis. Under the delta parameterization, the latent variance of each ordered categorical indicators is modeled in terms of a scale parameter which is the inverse of the standard deviation of a latent response variable. Scale parameters are allowed to vary across groups to estimate the across group differences of the variance of each latent response variable. Although the delta parameterization method has computational advantage in model estimation (Muthén and Asparouhov 2002), it has other disadvantages in addition to the inability of applying constraints on residual variances: Three different sources – differences in factor loadings, factor variances, and residual variances –can contribute to the differences of scale parameters across groups and these sources cannot be distinguished using delta parameterization (Muthén and Asparouhov 2002). With the theta parameterization method, this disadvantage can be circumvented. However, in the example analyses, corresponding models using the theta parametrization did not converge, even after repeated attempts. Even though the R2's associated with the genetic and environmental factors in Tables 2, 3, 4, 5 did not show appreciable differences across groups, it is still possible that the differences in scale parameters are an artifact of differences in other parameters across groups. In spite of the limitations of the delta parameterization, given the computational burdens of estimating the proposed model with ordered categorical variables, the delta parameterization appears to be an attractive alternative of specifying the model.

Finally, the model specification with identification constraints outlined for the general ordered categorical case cannot be applied when indicator variables are dichotomous, in which only a single threshold can be estimated for each indicator variable. Differences of means and variances of latent response variables in the non-reference groups are estimated based on two equally constrained thresholds across groups (Equation 6). Because a dichotomous variable has only one threshold, it provides only a reference point to estimate mean differences across groups Multiple-group factor models with dichotomous variables can be identified by setting the variances of the latent response variables to fixed uniform reference values (usually one) (Millsap and Yun-Tein 2004) permitting mean differences to be estimated. Although it may be argued that this is a fundamental limitation of the data and not the proposed statistical model, it should be noted that many psychological measures used in behavior genetics studies are dichotomous in nature (e.g., diagnosis classifications or symptom observations). Although it is possible to specify the proposed model for such cases, researchers must keep in mind that entirely plausible alternative models based on group variability, and not group mean differences, may explain the data equally well.

While limitations of implementation and some arbitrariness of model specification exist, the model proposed in this study provides a method to identify group differences of ordered categorical variables due to genetic and environmental factors via genetic factor model of ordered categorical variables that can estimate the differences of factor means and variances across groups. Given that many variables used in behavior genetic studies are assessed using ordered categorical variables, the proposed model represents a reasonable extension of conventional genetic factor models to categorical data.

Acknowledgements

Preparation of this research was supported by grants to Kenneth J. Sher (R37 AA07231) and Andrew C. Heath (P50 AA11998) from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. This research was facilitated with access to the Australian Twin Registry, a national research resource supported by an Enabling Grant (ID 310667) from the National Health & Medical Research Council, and administered by The University of Melbourne. The authors are grateful to Dr. Nicholas G. Martin for providing access to the Australian Twin Registry data.

Technical Supplement A: Mathematical Details of Model Identification

Minimal constraints needed to identify the proposed model are:

The mean and variance of each latent response variable, yj*, are set to zero and one, respectively, in the reference groups.

The mean and variance of each factor are set to zero and one, respectively, in the reference groups.

Factor loadings are constrained to be equal across groups.

Intercept of each variable are set to zero in both reference and non-reference groups.

For three selected indicator variables, two thresholds are set to be equal across groups respectively.

This section outlines how factor means and distributions of latent response variables can be identified under minimal identification constraints. Denote observed variable j for twin i (i={1, 2}) in group g as yij(g) and its corresponding continuous latent response variable as yij*(g). Constraints (a) and (b) identify all the parameters in reference groups by providing the scale of latent response variables and factors, from which factor loadings and thresholds are estimated. Thresholds are estimated as z-scores which correspond to the cumulative proportions of each response category. Factor loadings in non-reference groups are identified by constraint (c). By constraint (e) the means and variances of selected three variables in non-reference groups are identified. Those three latent response variables in non-reference groups are denoted as y1*(n), y2*(n), and y3*(n). Subscripts identifying the first and second twin in the same pair are omitted because the order of twin is assumed to be randomly selected and the means and variances from each twin in the same pair are assumed to be the same (Neale and Cardon 1992). For the first latent response variable, y1*(n), in non-reference groups, denoting two thresholds constrained to be equal as τ11 and τ12, the mean and variance, μ1*(n) and σ12*(n), respectively, can be identified from the following.

| (10) |

z11(n) and z12(n) are z-scores correspond to the cumulative proportions for the first and second response categories, respectively, of y1*(n) in non-reference groups. The superscripts of group membership on τ11 and τ12 are omitted because they are set to be equal across groups. Because τ11 and τ12 are given from constraint (e), and z11(n) and z12(n) are given from data, the Equation 10 contain two unknowns, μ1*(n) and σ1*(n), with two equations. Therefore μ1*(n) and σ1*(n) can be identified as following.

If there are more than three response categories in y1*(n), the remaining thresholds can be identified from the mean and variance identified in Equations 10. Denoting the third threshold of y1*(n), as τ13(n) τ13(n) is identified from z-score corresponding third category.

Means, variances, and the rest of thresholds not included in constraints (e) for y2*(n) and y3*(n) can be identified in the same way.

Constraint (e), combined with constraints (c) and (d), identifies the means and variances of factors in the non-reference groups. The means of latent response variables in the non-reference groups selected in constraint (e) – μ1*(n), μ2*(n), and μ3*(n)– can be expressed as linear combinations of factor means differences from reference groups and factor loadings.

| (11) |

δ(n) is the factor mean difference from reference groups for each factor. There are three equations with three unknowns because factor loadings are identified by constraint (c), so δ(n) for each factor can be identified. Factor variances can be identified from polychoric correlations among y1*(n), y2*(n), and y3*(n).

| (12) |

ϕ(n) is the variance of each factor in non-reference groups and ρhk(n) is the polychoric correlation between variable h and k in non-reference groups. Because polychoric correlations are given from the data, factor loadings are given from constraints (c), and the variances of each latent response variables are given from Equations 10, Equation 12 consists of three equations with three unknowns. Thus, factor variances can be identified from Equation 12. The means and variances of latent response variables not included in constraint (e) can be identified from factor loadings constrained from constraint (c) and factor means identified from Equation 11. Denoting one of the latent response variable not included in constraint (e) as y4*(n) and its mean and variance as μ4*(n) and σ42*(n), respectively, μ4*(n) and σ42*(n) are identified from following.

| (13) |

| (14) |

Because the mean and variance of y4*(n) are identified the thresholds of y4*(n) can be identified from z-scores correspond to the cumulative proportions of each response categories. Denotingthe first threshold of y4*(n) as τ41(n),

| (15) |

and the rest of the thresholds of y4*(n) are identified likewise. Means, variances, and thresholds for the rest of the variables in the non-reference groups can be identified in the same way as in Equations 13-15. Thus, all parameters are identified.

Technical Supplement B: Description of sample Mplus Program

An excerpt of an Mplus program used for the racial sub-dimension is presented in Table 7 as a sample program code. Rather than going over general Mplus programming, the description of program is focused on the specification of the proposed model with Mplus. The details of Mplus programming are described in the Mplus User's Guide (Muthén and Muthén 2007). The Mplus program starts with Data statement which specifies the location of the data file. The Variable statement specifies the variables to be used and missing values and grouping variables. The Categorical statement specifies categorical variables. In the Grouping statement five groups are specified by the variable zygw1t1. Because the grouping variables cannot be used in combination, when more than one variable define groups, such as zygosity and gender in this case, grouping variable should be defined as a single variable beforehand. The Model statement specifies the overall model and model specific for each group should be specified after defining overall model. The model specific for each group is specified by Model statement followed by a group name. Latent factors are defined by By statement followed by indicator variables. The latent variables F1 through F3 are the additive genetic factor, common environmental factor, and unique environmental factor, respectively, for the first twin in the same family. Factors F4 through F6 are the same factors, respectively, for the second twin. The variable names without any parameter or bracket represent the variance of independent variables or residual variances of dependent variables. The variable names in the bracket [ ] represent the mean or intercept of the variable. The parameters can be labeled by the number in the parenthesis. The equality constraints can be applied by assigning the same label. Parameters for the twins in the same family are constrained to be equal. Labels of parameters are also used in the Model constraint option to apply non-linear constraints. Asterisks after the parameter indicate free parameters, and are often used to override Mplus to estimate the parameters fixed to constants by default. Asterisks are needed for the factor loadings because Mplus constrains the factor loading for the first indicator of each factor to one by default. The Symbol “@”fixes the parameter to a following value. The With statement specifies the covariance between variables. Regression on a covariate variable is specified via the On statement. Each phenotype indicator variables is regressed on the variable aget1. Regression coefficients for the same variable are constrained to be equal across groups by assigning the same label across groups. Because, unless specified, Mplus estimates the covariances between exogenous variables, covariances among factors should be explicitly set to zero. Thresholds are specified by the variable name with “$” sign in the bracket [ ]. The numbers following the “$”sign indicate the order of threshold. There are two thresholds ($1 and $2) because each item has three response categories. To estimate the thresholds in male groups which are not constrained to be equal to those in female groups, the labels different than in the overall model are used. Factor means and variances are also estimated in male groups by using labels different than labels in overall model statement. Scale parameter for each variable is specified by the variable name in the bracket { }. Scale parameters are estimated for male groups, while they are set to one in overall model statement. In the Model constraint option, non-linear constraints for covariance structure in male groups are specified to impose correct correlation structure in Equation 2.

Excerpt of Mplus program

Table 7.

| Title: Genetic Factor Model with the Means of Genetic and Environmental Factors Data: | |

| File is ‘ c: \ data\ozpairw.txt’; | ! the location of the data |

| Variable: | |

| Names are xfam xid sexw1t1 zygw1t1 w1t1a1 w1t1a2...; | |

| Usevariables are w1t1a1 ... w1t2A48 aget1; | ! list of variables to be used; |

| Categorical are w1t1a1 ... w1t2A48; | ! list of categorical variables; |

| Gouping is | |

| zygw1t1 (1=mzf, 2=mzm, 3=dzf, 4=dzm, 5=dzo); | ! specifying grouping variable; |

| Analysis: | |

| Type=general meanstructure H1; | ! specifying analysis options; |

| Param=delta; | |

| output: | ! Requesting the outputs to display; |

| standardized samp res; | |

| Model: | ! Overall model specification; |

| F1 by | ! F1 is additive genetic factor; |

| w1t1a1* (1) | ! for the first twin; |

| w1t1A17* (2) | |

| w1t1A30* (3) | |

| w1t1A33* (4) | |