Abstract

Purpose

Friendship networks are an important source of peer influence. However, existing network studies vary in terms of how they operationalize friendship and friend’s influence on adolescent substance use. This study uses social network analysis to characterize three types of friendship relations: (1) mutual or reciprocated, (2) directional, and (3) intimate friends. We then examine the relative effects of each friendship type on adolescent drinking and smoking behavior.

Methods

Using a saturated sample from the Add Health data, a nationally representative sample of high-school adolescents (N=2,533 nested in 12 schools), we computed the level of exposure to drinking and smoking of friends using a network exposure model, and their association with individual drinking and smoking using fixed effect models.

Results

Results indicated that the influence from (1) is stronger on adolescent substance use than (2), especially for smoking. Regarding the directionality of (2), adolescents are equally influenced by both nominating and nominated friends on their drinking and smoking behavior. Results for (3) indicated that the influence from “best friends” was weaker than the one from non-“best friends,” which indicates that the order of friend nomination may not matter as much as nomination reciprocation.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that considering different features of friendship relationships is important in evaluating friends’ influence on adolescent substance use. Related policy implications are discussed.

Keywords: social network analysis, friends’ influence, adolescent drinking alcohol, smoking cigarette, friendship network

A number of network studies on adolescent risk-taking behavior have demonstrated that one of the strongest influences on an adolescent’s substance use occurs within friendship networks. These studies have examined network influences (either as a main explanatory variable or one of the mediated or controlled variables) and shown a significant correlation between exposure to friends’ use of substances and the likelihood of individual self use, indicating that friendships matter in influencing individual behavior (1–11). A majority of adolescent health behavioral studies operationalize friends’ influence based on a respondent-centered neighborhood network composed of alters who are directly connected to the individual.

Although many studies have agreed that friendship networks are an important source of peer influence, studies vary in terms of how friends are defined and how their influence on adolescent substance use is operationalized. More specifically, many studies define friends as a respondent’s (or ego’s) nomination or outgoing ties, and then measure the friend’s influence based on the nominating friend’s substance use behavior. Conversely, other studies have defined friends as an alter’s nomination or incoming (7), and still other studies define friends as those who reciprocate their nominations (an ego nominates an alter as a friend, and the alter also nominates the ego as a friend) (6, 9). Furthermore, still other studies distinguish between a “best friend,” as being the first nominated friend and the remaining friends— examining both influences individually or separately (1, 8, 12). These variations in the friendship definition and the operationalizations raise the question of which peers (defined by directionality or strength) are more influential sources of social influence and also, which definitions may contribute to an over- or under-estimation of friendship effects. Table 1 shows an overview of the network studies from the literature that use different types of friendship definitions and their relation to adolescent substance use.

Table 1.

An Overview of Network Studies that Use Different Types of Friendship Definitions and Relations to Adolescent Substance Use

| (a) Article reference | (b) Friendship definition | (c) Key findings | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (c.1) Alcohol | (c.2) Cigarette | (c.3) Others substances & problem behavior | ||

| Alexander, et al. (2001) | (1) Nominated friends excluding best male/female friend nomination | Peer networks with at least half of the members smoked significantly increased the risk of current smoking | ||

| (2) First named male and female friend named on the list of friendship nominations (best friend) | Having one or two best friends that smoked significantly increased the risk of current smoking | |||

| Ali & Dwyer (2009, 2010) | Nominated friends | An increase in friends’ smoking rates by 10% increases the likelihood of ever smoking by 5%. | An increase in friends’ drinking rates by 10% increase the likelihood of past 12-month drinking by roughly more than 2% | |

| Cleveland, et al. (2003) | Nominated friends | Association between individual and friends’ alcohol use varied according to school levels of alcohol use | Association between individual and friends’ smoking cigarette varied according to school levels of smoking | |

| Crosnoe et al.(2004) | Nominated friends | Association between frequent drinking and achievement varied by the level of drinking among friends | ||

| Ennett, et al. (2006) | (1) A best friends reciprocate | Adolescents with a best friend who reciprocated had significantly lower odds of past 3-months cigarette smoking at ages 11 and 13 | ||

| Ennett, et al. (2006) | (2) A set of all alters nominated by the adolescent and alters who nominate the adolescent (network neighborhood) | Adolescents with higher density network neighborhoods had significantly lower odds of past 3-month alcohol use at ages 13 | Adolescents with higher density network neighborhoods had significantly lower odds of past 3-month smoking at age 13 and 15 | Adolescents with higher density network neighborhoods had significantly lower odds of past 3-month marijuana use at age 15 |

| Fujimoto et al. (in press) | Nominated friends | Adolescents with higher proportion of friend who smoke were more likely to smoke | ||

| Hall & Valente (2007) | The number of friendship nominations an adolescent receives(peer influence) | Smokers’ influence predicts the selection of smokers as friends, and serves as a protective effect when ties were not reciprocated. | ||

| Hayne (2001) | Nominated friends | Friends’ delinquency (including cigarette use, alcohol use, got drunk) was associated with an individual’s own delinquency involvement, which was conditioned on density of friendship network and adolescent’s centrality and popularity | ||

| Kobus & Henry (2010) | Reciprocated friends | No effect on 6-month alcohol use | No significant effect on 6-month cigarette use | Significant positive effect on 6-month marijuana use |

| Mounts & Steinberg (1995) | First friend named on the list (closest friend) | Friend’s drug use (alcohol, marijuana, and other drugs) predicted changes in adolescent's use, especially for adolescents whose parents are less authoritative | ||

| Urberg (1997) | (1) First friend named on the list of friendship nominations (closest friend) | Close friend’s use significantly predicted the initiation and transition into current alcohol use | Close friend’s use significantly predicted the initiation of smoking | |

| Urberg (1997) | (2) Groups of adolescents who are connected by reciprocal friendship choices excluding the adolescent and the first-listed friend (friendship groups) | Friendship group use significantly predicted the transition into current use | ||

In an attempt to answer this question, we systematically construct different operationalizations of friendship and measure the corresponding friends’ influence on adolescent alcohol use and cigarette smoking. For our real-world dataset, we used the saturated school sample of National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health), a nationally representative school-based sample of high-school adolescents in the United States collected during 1994–95 (13). This study aims at identifying some of the features or types of friendships that are most likely to affect adolescent alcohol use and cigarette smoking by computing the level of exposure to friends’ behavior and their associations with individual behavior.

FRIENDSHIPS AND INFLUENCE

Berndt (1992) notes that the dominant theorization on the effects of friendship influence is characterized by two perspectives of the influence of: (1) friendship features, and (2) friendship behaviors (or attitudes). The former perspective emphasizes that social influence derives from the features of relationships such as mutual liking and intimacy. The latter perspective emphasizes the negative influence derived from friends having undesirable attitudes and/or behaviors (14).

The current study attempts to combine these two major theoretical perspectives of friendship features and behavior of friends by examining the effects of friendship influence on adolescent alcohol and cigarette use. Based on these two perspectives, this study categorizes the features of friendship into (1) mutuality in friendship (reciprocated versus non-reciprocated friendship), (2) directionality in friendship (i.e., influence from ego-nominating friends or being nominating by friends) by partitioning the influence of non-reciprocated friends from (1), and (3) intimacy in friendship (i.e., best friends versus other friends), and then it examines how exposure to friend behaviors based on these different friendship definitions affect adolescent alcohol and cigarette use.

Mutuality and directionality in friendship

The importance of mutual friendships on health-related behaviors such as obesity, smoking, and alcohol consumption has been reported by a series of social network studies among adults (15–17). These studies have reported that the influence from mutual friendships were the strongest, followed by the influence from ego-perceived friends (outgoing-only tie)1, and the influence from alter-perceived friends (incoming-only tie)2.

In the context of friendship networks, reciprocated friendships are believed to be substantially different from non-reciprocated ones (18), involving stronger emotional support and social capital derived from mutually agreed upon expectations and norms (19). In contrast, non-reciprocated friendships may involve a power imbalance between the two individuals (18). Best friends are more influential than other individuals in the overall peer group (20). Therefore, the first hypothesis is that influence from mutual friendships has stronger influence on adolescent drinking and smoking than non-mutual friendships.

Friends’ influence might also occur from the admiration and/or respect adolescents have for their friends. They may be influenced by these friends simply because they trust their judgment (14). Some network studies have emphasized the effect of directionality (or asymmetry) of friendships on adolescent substance use behavior. For example, Michell & Amos (1997) describe friendship group structure as hierarchical; this hierarchy was associated with smoking behavior for girls in which “top” girls were more likely to be smokers (21). Studies have shown that popular students were more likely to be become smokers before their less popular peers (22) especially in school environments where prevalence of smoking is high (1). Therefore, the second hypothesis is that the influence from friends that the adolescents admire (un-reciprocated ego-nominating friend) has a stronger effect on adolescent drinking or smoking than the one from friends to whom they do not nominate (un-reciprocated alter-nominating friends).

Intimacy in friendship

Intimacy becomes a central feature of friendship in early adolescence (14), so the class of friendship (best friendship and friendship group) may also matter in affecting different types of substance use. Existing studies have reported that best friends had particularly salient predictors of adolescent substance use compared to other social relationships, possibly because adolescents spend more time and are more invested in their closest friends (23, 24). The current study assumes that adolescents are more likely to be influenced by their closest friend (defined as the best friend) than other friends. Therefore, the third hypothesis is that the influence from the best friend has a stronger effect on adolescent drinking or smoking than influences of the remaining friends on drinking and smoking behavior.

This study tests the aforementioned three hypotheses by using a network exposure model, which allows us to operationalize different definitions of friendship by computing the level of exposures by friends of various kinds who drink alcohol or smoke cigarettes. These modeling methods provide essential information on the relative contributions of different types of friendships on alcohol and cigarette use.

DATA AND METHODS

Sample

This study uses data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health), which consists of a nationally representative sample of adolescents who were in Grades 7–12 in randomly selected schools3 in the United States during 1994–95 (13). All students from 7th through 12th graders who attended on the day of interview (N=90,118) completed the 45 minute paper-and-pencil In-School questionnaire. The In-School questionnaire asks students about general information such as basic demographic characteristics, friends, and health related risk behavior. It also asks students to nominate their 5 best male and 5 best female friends from a school roster (= 10 friends for both4) and these friendship nominations are recorded by the student identification number in the school rosters, allowing the creation of social network data5. Adolescents in grades 7–12 (n=20,745 in 132 schools) were sampled from the pool of participants in the In-School Survey to participate in the In-Home Interview where students were asked to respond to more extensive questions on sensitive topics such as substance use and sexual behavior6. Additionally, an In-Home Parent Interview was conducted at the same time with In-Home Student Interview.

The current study used both the In-School Survey and the Wave I In-Home Student and Parent Interview Data7. In the Wave I In-Home Interview data, there is a special “saturated” sample of 16 schools where all students enrolled in the school were also interviewed at home. Our study used the saturated sample since it allows us to construct complete friendship network data, all of which can be linked with In-Home Interview information about past-year drinking or current smoking. The data are used as an attribute vector of network exposure model (discussed in the following section) or as dependent variables in our study. Our study excluded three schools for having less than 70 percent of the students completed the questionnaire as recommended by the empirical literature (25), as well as one additional school because of invalid student identification numbers. The final analytic sample consisted of 2,533 students nested in 12 high-schools with both In-School Surveys and In-Home Interviews. We employed multiple imputation methods by using switching regression, an iterative multivariable regression technique of multiple imputation by chained equations (26) implemented in Stata 11 to deal with any missing values in at least one of our covariates (16 % of the total sample) for the study variables8.

Measures of outcome variables

The study outcomes of past-year drinking and current smoking were measured using the Wave I In-Home interview. For past-year drinking, adolescents reported how often they drank alcohol in the past year9, and this was coded into a dummy variable of past-year drinkers versus non past-year drinkers. As for current smoking10, adolescents reported how often they smoked cigarettes in the past 30 days, and smoking was dichotomized into a dummy variable of current smokers versus non-current smokers. The rationale for using the dichotomous drinking and smoking was due to the skewed distribution of the original measures, and to create a meaningful categorical variable so that the results can be interpreted easily.

Measures of friends’ influence

The current study uses the network exposure model (27) to model a binary behavioral outcome of alcohol and cigarette use as a function of various operationalizations of friends’ effects and other risk factors.

The general formula of exposure E is defined in the following way:

| (1) |

where E̲ is the exposure vector, Wij is a social network weight matrix that represents a given relation from i to j, and yj is a vector of j’s (alter’s) behavioral attribute (j = 1, ⋯ , N). There are two components in operationalizing W matrix where the first component addresses the issues of which alters constitute ego’s frame of reference, and the second component deals with the choice for a particular normalization that determines how social influence is allocated among these alters (28). Our study specifies two ways of operationalizing the W matrix in terms of specifying ego’s fame of reference based on outdegrees and indegrees11.

Specification of influence matrix W

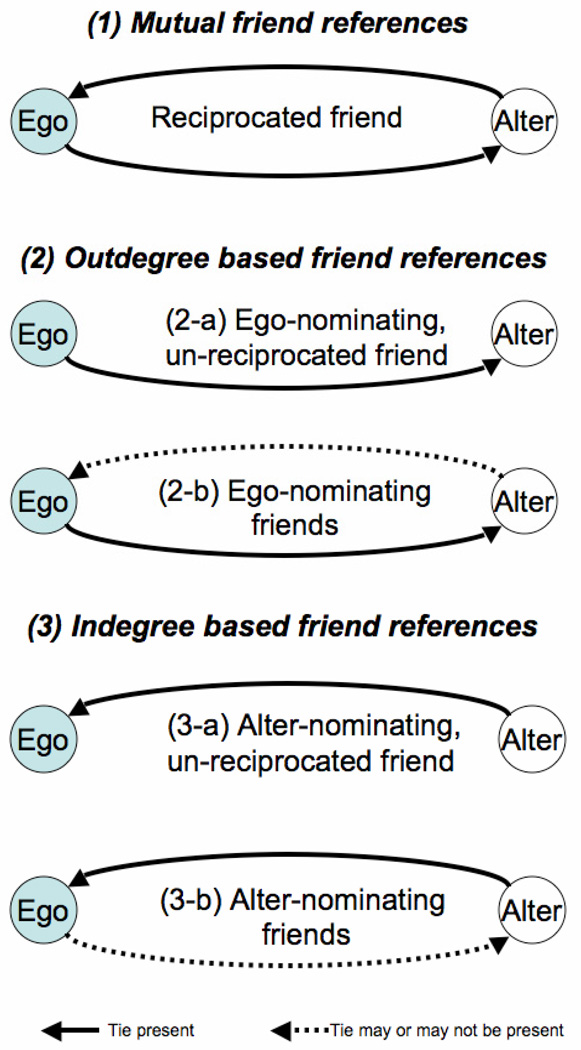

We operationalize friends’ influence based on ego’s frame of reference: (1) influence from mutual friends based on symmetric friendship, (2) outdegree-based influence where ego is influenced by the alters whom s/he nominates as friends, and (3) indegree-based influence where ego is influenced by the alters who nominate ego as friends. For (2) and (3), we further operationalize influence from (a) un-reciprocated alters, and (b) alters regardless of reciprocation. Based on these classifications, we specified five types of friends’ influence from (1) mutually nominated alters, (2-a) ego-nominating un-reciprocated friends, (2-b) ego-nominating friends, (3-a) alter-nominating ego unreciprocated friends, and (3-b) alter-nominating ego regardless of reciprocation. These different operationalizations constitute the W terms (matrix) in the network exposure model12. In defining the W matrix, we specified a minimally symmetrized (deleted unreciprocated ties) matrix of X for (1), the original friendship matrix X without reciprocated ties for (2-a) and (3-a), and the original friendship matrix X for (2-b) and (3-b). The Figure 1 describes all seven types of friends’ influence.

Figure 1.

Five types of ego’s frame of reference in friends’ influence.

For friendship intimacy, we operationalized two types of friends’ influence using outdegree-based influence, which is (4-a) influence from the first nominated friends on the list of friendship nominations, and (4-b) influence from the rest of friends excluding the first-listed friend. The W matrix for (4-a) was constructed only with the first female and first male friend nominations13. The W matrix for (4-b) was specified using the original friendship matrix X but excluding the first female and the first male friend nominations. We specified both outcome variables of past-year drinking and current smoking as alter’s attribute vector, y, to compute the corresponding exposure terms.

Measures of control variables

Socio-demographic control variables were identified in the past as correlates of alcohol use in age (in years), female gender, race/ethnicity (dummy variables for Hispanic/Latino, Non-Hispanic white, African American, with Others as a reference category), self-reported academic grade (average GPA14), and parental education (maximum level in the household15). Other control variables of public assistance (received by resident parent), emotional state (modified CES-D16 for depressive symptomatology), accessibility of alcohol or cigarette (1=easily; 0=not easily) were used. Additionally, we controlled for network positional variables of popularity and isolates based on existing network studies (1, 22). Furthermore, the In-School survey allowed respondents to nominate friends who did not attend the same school as the adolescent, and so we counted the ties to both non-school friends and sister-school friends and used the proportion of these ties as one of the control variables. To minimize the potential problem of peer selection (adolescents choosing friends based on their behavior), we controlled for classmates’ drinking or smoking behavior as another measure of peer influence, which was measured by the proportion of students (excluding the respondent) in the respondent’s grade within the school that drink or smoke (2, 3). The rationale is that peer measures drawn from classmates within a grade are not driven by peer selection and therefore partially address the selection problem (2, 3, 29, 30).

Statistical method

We model adolescent past-year drinking and current smoking as a function of the various network exposure terms (E) and the control variables. A conditional fixed effect logistic regression model17 is used to control for school-level fixed effects which accounts for environmental conditions shared by students in the same school. (31, 32).

RESULTS

Table 2 shows summary statistics for the outcome, exposure and controlled variables. Table 3 reports the estimated odds ratio of conditional school-level fixed effect model for past-year smoking and current smoking, adjusted for the control variables. The models were estimated separately for each friendship operationalization. These odds ratios are directly comparable to each other because each friendship operationalization is on the same scale. Figure 2 displays a bar graph with the estimated odds ratio (with lower and upper 95 % confidence intervals) to visually compare the effect sizes.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics for Outcome, Demographic, and Network Measures (N=2,533)

| Mean (SD; Min, Max) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Past Drinking (Last 12 Months) | 49 % | |

| Current Smoking (Last 30 Days) | 27 % | |

| Age | 15.49 (1.49; 12, 19) | |

| Female | 50 % | |

| Race Hispanic | 21 % | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 48 % | |

| African American | 12 % | |

| Others | 19 % | |

| Grade (GPA) | 2.46 (.87; .25, 4.00) | |

| Parental Education | 2.90 (1.18; 1, 5) | |

| Public Assistance | 6 % | |

| Emotional State (CES-D) | 11.79 (7.42; 0, 52) | |

| Popularity (indegree) | 4.83 (3.96; 0, 29) | |

| Isolates | 3 % | |

| Non-school nomination | 0.17 (0.27; 0, 1) | |

| Past Year Drinking | Current Smoking | |

| Easily accessible to alcohol or cig | 29 % | 31 % |

| Classmates’ drink/smoke (proportion of drinkers or smokers in the respondent’s grade and school) | 0.37 (0.14; 0, 0.89) | 0.20 (0.12; 0, 0.58) |

| Friends’ exposure (proportion of friends who drink or smoke) | ||

| (1) Influence from mutual friends | 0.33 (0.41; 0, 1) | 0.18 (0.33; 0, 1) |

| (2) Outdegree-based influence | ||

| (2-a) from un-reciprocated alters | 0.40 (0.39; 0, 1) | 0.23 (0.33; 0, 1) |

| (2-b) from alters in general | 0.42 (0.36; 0, 1) | 0.24 (0.31; 0, 1) |

| (3) Indegree-based influence | ||

| (3-a) from un-reciprocated alters | 0.37 (0.40; 0, 1) | 0.19 (0.31; 0, 1) |

| (3-b) from alters in general | 0.43 (0.37; 0, 1) | 0.22 (0.30; 0, 1) |

| (4) Intimacy of friendship | ||

| (4-a) from the best friends | 0.33 (0.44; 0, 1) | 0.18 (0.36; 0, 1) |

| (4-b) from rest of friends | 0.41 (0.37; 0, 1) | 0.22 (0.31; 0, 1) |

Table 3.

Estimated Adjusted Odds Ratio of Conditional School-Level Fixed Effect Model

| Network Exposure | Past-year drinking | Current smoking |

|---|---|---|

| (1) Influence from mutual friends | 2.07*** (0.25; 1.64, 2.61) |

4.44*** (0.69; 3.27, 6.01) |

| (2) Outdegree-based influence | ||

| (2-a) from un-reciprocated alters | 2.02*** (0.25; 1.59, 2.56) |

2.89*** (0.46; 2.11, 3.96) |

| (2-b) from alters in general | 3.29*** (0.47; 2.49, 4.35) |

4.96*** (0.90; 3.47, 7.07) |

| (3) Indegree-based influence | ||

| (3-a) from un-reciprocated alters | 1.97*** (0.24; 1.56, 2.50) |

2.73*** (0.44; 1.99, 3.74) |

| (3-b) from alters in general | 3.18*** (0.43; 2.44, 4.14) |

5.20*** (0.91; 3.69, 7.31) |

| (4) Intimacy of friendship | ||

| (4-a) from the best friends | 1.55*** (0.15; 1.29, 1.88) |

2.39*** (0.29; 1.88, 3.02) |

| (4-b) from rest of friends | 2.62*** (0.35; 2.01, 3.40) |

3.32*** (0.57; 2.37, 4.64) |

p<.001, parentheses show standard errors; upper and lower 95 % confidence intervals. Adjusted for age, gender, ethnicity, academic grade, parental education, public assistance, emotional state, popularity, isolation, proportion of non-school nominations, availability of alcohol or cigarettes in the home, and classmates’ drinking or smoking. Each friendship measure based on a given operationalization of friend was estimated separately.

Figure 2.

Estimated odds ratios (middle line) with the upper and lower 95 % confidence intervals for five types of friends’ influence and two types of intimacy of friendship on the x-axis

All friend adjusted odds ratios were significant at alpha=0.001 level. The effect from mutual friends (AOR=2.07) on past-year drinking was slightly higher than exposures from outdegree-based un-reciprocated alters (AOR=2.02) or indegree-based unreciprocated alters (AOR=1.97) on past-year drinking, but the magnitudes across all three were similar. However, the effect of exposure from mutual friends on current smoking (AOR=4.44) was almost 1.6 times higher than the effects of exposure from outdegree-based un-reciprocated alters (AOR=2.89) or indegree-based un-reciprocated alters (AOR=2.73) on current smoking. The odds ratio for the mutual friendship (AOR=4.44) falls above the upper 95% confidence intervals for both out-degree- (upper 95% CI=3.96) and indegree-based (upper 95% CI=3.74) unreciprocated alters, which provides evidence that the differences in odds ratios were statistically significant. These results indicate mutuality in friendship matters only for current smoking, and partially support our first hypothesis.

Regarding directionality of friendship among non-reciprocated alters, the effect of ego-nominating friends (outdegree-based influence, AOR=2.02) was a little bit higher than the effect of alter-nominating friends (indegree-based influence, AOR=1.97) on past-year drinking, but these effects again were similar in magnitude. We obtained similar results with regards to the effect of directionality of friendship on current smoking (AOR= 2.89 for outdegree-based influence, and AOR=2.73 for indegree-based influence). These results minimally support the second hypothesis.

The magnitude of the effect of outdegree-based influence from alters regardless of reciprocation on past-year drinking (AOR=3.29) was much higher than the effect of influence from mutual friendship on past-year drinking (AOR=2.07). The former’s odds ratio falls above the upper 95% CI (=2.61) of the latter’s, and this result indicates that influence from non-reciprocated friends also contributes to the outdegree-based influence on past-year drinking. Similarly for current smoking, the results show that the effect of influence from alter-nominating friends regardless of reciprocation (AOR=5.20) was higher than the effect of influence from mutual friendship (AOR=4.44). However, the former’s odds ratio falls below upper 95% CI (=6.01) of the latter’s, which fails to provide significant differences in the odds ratios.

With regards to the intimacy of friendships, the results have shown that the influence from the “best friends” was actually smaller than the combined influence of the remaining friends for past-year drinking (AOR=1.55 for best-friends influence, and AOR=2.62 for the rest of the friends). The odds ratio for the influence from the rest of the friends falls above the lower 95% CI of 1.88 for the best friends, which indicates that the difference in odds ratios are significant. We obtained a similar tendency for smoking (AOR=2.39 for best friends influence, and AOR=3.32 for the rest of the friends)18, but this difference was not statistically significant.

A caveat in the interpretation of these results regarding friends’ influence mechanisms is that there is a potential confound due to peer selection. These results have shown that there was no significant classmates’ influence on current smoking for all of our models, while classmates’ influence was significant for some types of friends’ influence at alpha=0.05 level for drinking outcome19.

DISCUSSION

The current study is the first empirical network study to systematically examine how friends’ influence behaviors vary based on differing operationalizations of friendship. Using a network exposure model, friendship directionality and intimacy effects on adolescent drinking and smoking behavior were estimated. The results indicated that the influence from mutual friendships had a stronger effect on adolescent smoking behavior than the one from non-mutual friendships. However, mutuality in friendship did not appear to be as important in influencing adolescent drinking behavior.

We also found that the directionality of friends’ influence (either outdegree or indegree-based influence) did not matter for both drinking and smoking behavior. Adolescents were equally influenced by the friends they nominated and the ones who nominated ego. This result differs from the network influence observed in adult networks regarding other health-related behaviors. Our study indicates that the non-reciprocated friends also contribute to influencing adolescent drinking and smoking behavior20. These results suggest that operationalizing friends’ influence based on mutual friendships might underestimate the friends’ influence since it omits undirected ties in the exposure calculation. Lastly, this study indicates that friends’ influence on substance use depends more on reciprocation rather than the rank order of the nomination or the strength of the ties21.

These results, however, are tempered by some limitations in data availability and in some methodological issues. First, our results are limited in their ability to understand the process of peer selection. It has generally been agreed that both processes of peer selection and influence account for the similarity in substance use among adolescents (7, 8, 33–38), also known as the “reflection problem.” Prior network studies have taken a two-stage least-square estimation method to address the reflection problem, and their results showed that peer effects are important determinants in both smoking and drinking behavior even after controlling for the potential biases (2, 3). Our estimation procedure may have a limitation in directly addressing the reflection problem and identifying accurately the effect of peer influence as disentangled from peer selection, which may result in a potential overestimation of peer influence.

Second, the network exposure model does not account for the network dependencies that arise within the community from network structure. The Exponential Random Graph Model (ERGM), which has been widely used as a method of directly modeling underlying structural forces in combination to actor attributes to generate observed social network data, deals with network dependencies, but may be limited in its ability to directly model peer influence.

Despite these limitations, this study demonstrates that the operationalization of friendships can be important determinants in evaluating friends’ influence on adolescent substance use. We hope these findings will serve as guidelines for network researchers who want to use friends’ influence as main explanatory variable or control variables in their analysis. These findings may also inform policy implications for school-based substance use prevention programs that include the social-influence model. For example, interventions using network data need to decide whether the data should be symmetrized and whether best friends or non-reciprocated friends should be included in the analyses.

Implications and Contribution Summary Statement.

Using Add Health data, we employ social network analysis to systematically decompose how different operationalizations of friendship and the corresponding measurement of friends’ influence vary when applied to adolescent alcohol use and cigarette smoking, which can serve as a guideline for network researchers in the operationalization of friendship influence.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported primarily by Award Number K99AA019699 (PI: Kayo Fujimoto) and partially from 1RC1AA019239-01 (PI: Thomas W. Valente) from the National Institute On Alcohol Abuse And Alcoholism. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute On Alcohol Abuse And Alcoholism or the National Institutes of Health. This research uses data from Add Health, a program project directed by Kathleen Mullan Harris and designed by J. Richard Udry, Peter S. Bearman, and Kathleen Mullan Harris at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and funded by grant P01-HD31921 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, with cooperative funding from 23 other federal agencies and foundations. Special acknowledgment is due Ronald R. Rindfuss and Barbara Entwisle for assistance in the original design. Information on how to obtain the Add Health data files is available on the Add Health website (http://www.cpc.unc.edu/addhealth). No direct support was received from grant P01-HD31921 for this analysis. We acknowledge Erik Lindsley, Janet Okamoto, and anonymous reviewers for their contributions to completing this project.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

In the case of alcohol consumption, the authors cautioned their results by pointing out the overlapping CIs indicate that the difference in the effect size may not be significant.

Christakis and Fowler (2007) observe that asymmetry of friendship may arise from the fact that the person who identifies another person as a friend esteems the other person, indicating that nomination (rather than being nominated) is important in the process of interpersonal influence.

Add Health uses the Quality Education Database, an exhaustive list of American high schools, as the primary sampling frame, and systematic sampling methods and implicit stratification ensure that the 80 high schools selected are representative of US schools with respect to region of country, level of urbanization (defined by U.S. Census Bureau), size, school type (e.g., public, private, and parochial), and racial composition. For each high school selected, a single junior high or middle feeder school was selected with a probability of being proportional to the percentage of the high school’s entering class that came from that feeder.

An advantage in employing gender-segregating friendship nomination could be that it separates the same-sex and mixed-sex friendship information so that researchers can examine peer influences that may differ by gender. A disadvantage could be that we do not know the relative strengths of the ties between each set. The Add Health data is more likely to include weak ties between members of different sexes, resulting in weaker peer influence measures in Add Health and a reduction in the likelihood of detecting peer influence across genders.

Wave I In-Home Student Interview also contains information on friendship nominations. However, many respondents nominated friends outside of the school and so the network information was not complete. Therefore, this study used only the In-School network information to compute any network measurements.

They used the Audio Computer-Assisted Self Interview (ACASI) to ensure confidentiality.

Wave I In-Home Parent Interview data were used to extract socioeconomic information.

Regarding pre-imputation missing data, out of the total analytic sample (N = 2,533) there was 0.16 % for past-drinking outcome variable, 0.79 % for current smoking outcome variable, 0.08 % for age, 0.36 % for gender, 1.70 % for race, 9.28 % for academic grade, 3.51 % for parent education, 0.67 % for public assistance, 0.32 % for CES-D, 0.43 % for accessibility of alcohol, and 0.47 % for accessibility of cigarette.

Drinking level was assessed on a scale ranging from 0 to 6: 0=never, 1 = 1–2 days in the past 12 months, 2 = once a month or less (3–12 times in the past 12 months), 3 = 2–3 days a month, 4 = 1–2 days a week, 5 = 3–5 days a week, and 6 = everyday.

There were no specific questionnaire items that directly asked for “past-year smoking” or “current drinking” in the In-Home Interview data.

For the outdegree-based operationalization of W matrix, exposure is computed by multiplying Xij by the nominated alters’ behavior yj and normalize by row-sum of Xij (i.e., actor i’s outdegree, Xi+), the resulting row-normalized exposure of Ei measures the proportion of nominated alter js who have behavioral attribute of yj in an ego network. For the indegree-based operationalization of W matrix, exposure is computed the same as the outdegree-based operationalization, but Xij is transposed. We specify both outdegree and indegree-based operationalizations of the W.

Note that (2-b) is the logical union of (1) and (2-a), and likewise, (3-b) is the logical union of (1) and (3-a).

Since not all adolescents nominated both males and females, we created a dummy variable of “no best friend exposure” and “non-zero exposure from best friends who drink alcohol or smoke” that includes “adolescents who nominated two best friends both of whom drink/smoke,” “two best friends and one who drinks/smokes,” or “one best friend who drinks/smokes” (Alexander and colleagues 2001).

Students reported their grades (1=D/F, 2=C, 3=B, and 4=A) on classes of math, science, English, and social studies in the past year. We took the value for each valid class and divided by the number of classes in which there was a valid value.

We created a scaled-down measure with 5 categories for both parents (1=less than high school; 2=high school, 3=some college, 4=college graduates, and 5=graduate education), and then took the highest value available.

In this modified version of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale (Radloff and Locke 1986), respondents reported how often they experienced 19 symptoms of depression by answering a list of the ways they have felt or behaved during the past week. The responses scale from 0=never or rarely, 1=sometimes, 2=a lot of the time, 3=most of the time or all of the time. We summed up these responses over 19 items. Higher scores indicate more severe depressive symptoms.

We employed a multilevel modeling approach with the school treated as a fixed effect (and this is considered a special case of the random effects model) in order to model the multilevel nature of the data (i.e., individuals nested within schools).

We speculate that drinking and smoking may be social behaviors that are done with more than just a person’s best male or female friends which accounts for non-best friend influences.

Our results showed that classmates’ influence was significant for the following friends’ influence: (1) influence from mutual friends (AOR=4.70; p<0.05), (2-a) outdegree-based influence from un-reciprocated alters (AOR=4.65; p<0.05), (3-a) indegree-based influence from un-reciprocated alters (AOR=4.82; p<0.05), (4-a) intimacy of friendship based on the best friend (AOR=5.89; p<0.01), and (4-b) intimacy of friendship based on rest of friends (AOR=3.95; p<0.05). Under these types of friendship, there is a possibility that our results are somewhat confounded with peer selection (although significance level is much lower than that of friends’ influence), and this caveat would need to be taken into account when interpreting the results.

We also found that gender interaction with influence from each type of friendship was significant only for the effect of (3-b) indegree-based influence from alters in general on past-year drinking (OR=1.72; SE=0.43; p<0.05).

It may be that drinking and smoking may be a more social behavior, which extends one’s best male/female friends, and thus involves non-best friends.

References

- 1.Alexander C, Piazza M, Mekos D, Valente TW. Peers, schools, and adolescent cigarette smoking. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2001;29(1):22–30. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00210-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ali MM, Dwyer DS. Estimating peer effects in adolescent smoking behavior: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2009;45(4):402–408. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ali MM, Dwyer DS. Social network effects in alcohol consumption among adolescents. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35(4):337–342. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crosnoe R. The connection between academic failure and adolescent drinking in secondary school. Sociology of Education. 2006;79(1):44–60. doi: 10.1177/003804070607900103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crosnoe R, Muller C, Frank KA. Peer context and the consequences of adolescent drinking. Social Problems. 2004;51(2):288–304. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ennett ST, Bauman KE, Hussong A, Faris R, Foshee VA, Cai L, et al. The peer context of adolescent substance use: Findings from social network analysis. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2006;16(2):159–186. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hall JA, Valente TW. Adolescent smoking networks: The effects of influence and selection on future smoking. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(12):3054–3059. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Urberg KA, Degirmencioglu SM, Pilgrim C. Close friend and group influence on adolescent cigarette smoking and alcohol use. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33(5):834–844. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.5.834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kobus K, Henry DB. Interplay of network position and peer substance use in early adolescent cigarette, alcohol, and marijuana. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2010;30(2):225–245. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cleveland H, Wiebe RP. The moderation of adolescent-to-peer similarity in tobacco and alcohol use by school levels of substance use. Child Development. 2003;74(1):279–291. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fujimoto K, Unger J, Valente TW. Network method of measuring affiliation-based peer influence: Assessing the influences on teammates smokers on adolescent smoking. Child Development. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01729.x. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mounts NS, Steinberg L. An ecological analysis of peer influence on adolescent grade point average and drug use. Developmental Psychology. 1995;31(6):915–922. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris KM. The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health), Waves I & II, 1994–1996; Wave III, 2001–2002; Wave IV, 2007–2009 [machine-readable data file and documentation] Chapel Hill, NC: Carolina Population Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berndt TJ. Friendship and Friends' Influence in Adolescence. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 1992;1(5):156–159. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Christakis NA, Fowler JH. The spread of obesity in a large social network over 32 years. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;357:370–379. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa066082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Christakis NA, Fowler JH. The collective dynamics of smoking in a large social network. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;(358):2249–2258. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0706154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosenquist JN, Murabito J, Fowler JH, Christakis NA. The spread of alcohol consumption behavior in a large social network. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2010;152:426–433. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-152-7-201004060-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vaquera E, Kao G. Do you like me as much as I like you? Friendship reciprocity and its effects on school outcomes among adolescents. Social Science Research 37. 2008;37:55–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coleman JC. Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology. 1988;94:95–120. 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Epstein J, Karweit N. Friends in School: Patterns of Selection and Influence in Secondary School. New York: Academic Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Michell L, Amos A. Girls, Pecking order and smoking. Social Science and Medicine. 1997;44(12):1861–1869. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00295-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Valente TW, Unger JB, Johnson AC. Do popular students smoke?: The association between popularity and smoking among middle school students. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2005;37:323–329. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hussong AM. Differentiating peer contexts and risk for adolescent substance use. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2002;31(3):207–220. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown BB, Dolcini MM, Leventhal A. Transformations in peer relationships at adolescence: Implications for healthrelated behavior. In: Schulenberg J, Maggs JL, Hurrelmann K, editors. Health Risks and Developmental Transitions During Adolescence. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1997. pp. 161–189. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kossinets G. Effects of missing data in social networks. Social Networks. 2006;28:247–268. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Royston P. Multiple imputation of missing values. Stata Journal. 2004;4(3):227–241. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Valente TW. Network Models of the Diffusion of Innovations. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leenders RAJ. Modeling social influence through network autocorrelation: constructing the weight matrix. Social Networks. 2002;24:21–47. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clark A, Loheac Y. It wasn't me, it was them! Social influence in risky behavior by adolescents. Journal of Health Economics. 2007;26(4):763–784. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fletcher JM. Social interactions and smoking: Evidence using multiple student cohorts, insrumental variables, and school fixed effects. Health Economics. 2009;19(4):466–484. doi: 10.1002/hec.1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cohen-Cole E, Fletcher JM. Detecting implausible social network effects in acne, height, and headaches: Longitudinal analysis. British Medical Journal. 2008;337(a):2533. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a2533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cohen-Cole E, Fletcher JM. Is Obesity contagious? Social networks vs. environmental factors in the obesity epidemic. Journal of Health Economics. 2008;27(5):1382–1387. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Engeles RCME, Knibbe RA, Drop MJ, de Haan YT. Homogeneity of cigarette smoking within peer groups: influence or selection? Health Education & Behavior. 1997;24(6):801–811. doi: 10.1177/109019819702400613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ennett ST, Bauman KE. The contribution of influence and selection to adolescent peer group homogeneity: The case of adolescent cigarette smoking. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67(4):653–663. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.67.4.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fisher LA, Bauman KE. Influence and selection in the friend-adolescent relationship: findings from studies of adolescet smoking and drinking. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1988;18(4):289–314. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haynie DL. Delinquent peers revisited: Does network structure matter? American Journal of Sociology. 2001;106:1013–1057. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kirke DM. Chain reactions in adolescents' cigarette, alcohol and drug use: Similairty through peer influence or the patterning of ties in peer networks? Social Networks. 2004;26:3–28. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mercken L, Candel M, Willems P, de Vries H. Social influence and selection effects in the context of smoking behavior: Changes during early and mid adolescence. Health Psychology. 2009;28(1):73–82. doi: 10.1037/a0012791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]