Abstract

The sea slug Plakobranchus ocellatus (Sacoglossa, Gastropoda) retains photosynthetically active chloroplasts from ingested algae (functional kleptoplasts) in the epithelial cells of its digestive gland for up to 10 months. While its feeding behavior has not been observed in natural habitats, two hypotheses have been proposed: 1) adult P. ocellatus uses kleptoplasts to obtain photosynthates and nutritionally behaves as a photoautotroph without replenishing the kleptoplasts; or 2) it behaves as a mixotroph (photoautotroph and herbivorous consumer) and replenishes kleptoplasts continually or periodically. To address the question of which hypothesis is more likely, we examined the source algae for kleptoplasts and temporal changes in kleptoplast composition and nutritional contribution. By characterizing the temporal diversity of P. ocellatus kleptoplasts using rbcL sequences, we found that P. ocellatus harvests kleptoplasts from at least 8 different siphonous green algal species, that kleptoplasts from more than one species are present in each individual sea slug, and that the kleptoplast composition differs temporally. These results suggest that wild P. ocellatus often feed on multiple species of siphonous algae from which they continually obtain fresh chloroplasts. By estimating the trophic position of wild and starved P. ocellatus using the stable nitrogen isotopic composition of amino acids, we showed that despite the abundance of kleptoplasts, their photosynthates do not contribute greatly to the nutrition of wild P. ocellatus, but that kleptoplast photosynthates form a significant source of nutrition for starved sea slugs. The herbivorous nature of wild P. ocellatus is consistent with insights from molecular analyses indicating that kleptoplasts are frequently replenished from ingested algae, leading to the conclusion that natural populations of P. ocellatus do not rely on photosynthesis but mainly on the digestion of ingested algae.

Introduction

Since the discovery of “chloroplast retention” in Elysia atroviridis by Kawaguti & Yamasu [1], it has been widely accepted that many species of sacoglossan sea slugs (Sacoglossa, Gastropoda, Mollusca) retain chloroplasts of ingested algae in digestive gland cells [2]. A sequestered chloroplast is called a “kleptoplast” [3]. The kleptoplasts are not passed on to progeny, so new kleptoplasts must be acquired in each generation [4]–[7]. Food algae of sacoglossan species have been studied in laboratory feeding experiments. Most sacoglossan species have a fairly high feeding preference for one or a few algal species [7]–[9], and hence their kleptoplasts come from a limited number of source algae. For example, Bosellia mimetica only feed on Halimeda tuna [6]–[8] and algae ingested by Oxynoe antillarum are limited to 2 species: Caulerpa racemosa and C. sertularioides [7].

Kleptoplasts retain photosynthetic activity for a few days to several months in some sacoglossan species [10], [11]. Laboratory experiments showed that the photosynthetic products of kleptoplasts (e.g., sugars and amino acids) are transferred to and used by sea slugs when they are starved [12]–[14]. This “functional kleptoplasty” [15] permits sea slugs to have a mixotrophic lifestyle involving photosynthesis via kleptoplasts and heterotrophy by feeding on algae [16]. However, the relative importance of these feeding mechanisms under natural conditions has not been characterized in detail.

The retention period of functional kleptoplasts in the tropical Indo-Pacific species Plakobranchus ocellatus van Hasselt, 1824 has been estimated to be up to 10 months from linear extrapolation of the photosynthetic activity measured by pulse amplitude modulation (PAM) fluorometry [10], [17]. The natural algal source species for kleptoplasts in P. ocellatus have not been determined [17], [18], but P. ocellatus are known to feed on multiple siphonous green algae of the order Bryopsidales under artificial conditions, i.e., Chlorodesmis hildebrandtii, Rhipidosiphon javensis, Caulerpella ambigua, and Bryopsis sp. [18]–[20]. It has been proposed that once the sea slug acquires functional kleptoplasts, they are not replenished [21]. This hypothesis is based on the knowledge that the chlorophyll contents of kleptoplasts remain unaffected in starved P. ocellatus for 27 days under 500 ft-candle lighting ( = 109.5 µmol photons m−2 s−1 equivalent of incandescent light) [10], that P. ocellatus are mostly found on sandy beaches where potential food algae are rare [21], and that feeding behavior has never been observed in their natural habitats [21]. However, Dunlap [20] reported that the chlorophyll content and 14C-inorganic carbon fixation rate diminished after 2 months of incubation under outdoor lighting conditions, and concluded that kleptoplasts in P. ocellatus must be replaced continually or at periodic intervals to replace those that have degenerated. These two hypotheses remain to be examined. Before addressing which hypothesis is more likely, a number of questions must be answered. First, which algae are the sources of kleptoplasts for the sea slugs? Second, do kleptoplasts in each P. ocellatus individual derive from a single or multiple algal species? Finally, to what degree does the sea slug's nutrition depend on kleptoplast photosynthesis and on algivory?

To address these questions, we identified the source algae of kleptoplasts based on sequences of the RuBisCO (ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase) large subunit gene (rbcL), which is encoded in the chloroplast genome [9], [22], [23] and has been sequenced for a wide range of siphonous green algae [22]. We assessed the temporal kleptoplast composition in field-collected P. ocellatus to determine whether the sea slugs acquire kleptoplasts only once or repeatedly and estimated the trophic positions of the sea slugs in their natural habitat and during starvation in the laboratory based on the nitrogen isotopic composition of glutamic acid and phenylalanine [24], [25], which can be expected to serve as a proxy of the nutritional contribution of functional kleptoplasts to the sea slugs. Based on this combination of techniques, we aimed to gain insight into the ecological role of functional kleptoplasty in natural circumstances.

Materials and Methods

Sampling and DNA extraction of P. ocellatus

We collected P. ocellatus for DNA analyses by snorkeling or scuba diving in a 200-m×200-m near-shore area off Tenija, Okinawa, Japan (26°33′N 128°08′E). No permission was required for sample collection. Samples were taken each month from April to December 2005, and from May 2007 to April 2008. However, the sea slug was seldom found in winter (December 2005 and December 2007 to April 2008). Collected sea slugs were fixed in 99% ethanol at room temperature and preserved at −30°C until use.

With a DNeasy blood and tissue kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), the DNA of P. ocellatus was extracted from part of the parapodial tissue (about 5×5×2 mm) (Figure S1), which included the digestive gland (retaining kleptoplasts) but not the stomach [26]. Although a previous study showed chloroplasts on the outside of the stomach cells of P. ocellatus, no such “extracellular” chloroplasts were observed in the cavity of the parapodial digestive gland [26], and hence we believe that the sequences obtained did not include contaminant DNA from extracellular chloroplasts in the digestive tract.

Genetic analysis of P. ocellatus

Because it has been proposed that P. ocellatus is a cryptic species complex [19], [27], we checked the genetic homogeneity of the collected individuals by sequencing the mitochondrial 16S rRNA gene (mt16S rDNA). To identify the source algae of the kleptoplasts, rbcL in 7 individuals of P. ocellatus collected in nonconsecutive months were also sequenced. Fragments of rbcL and of mt16S rDNA were amplified by PCR with their respective primer sets (Table 1).

Table 1. Primer list for sequencing and T-RFLP.

| Gene | Primer name | Sequences (5′–3′) | Reference |

| 16S rDNA (on P. ocellatus (mitochondria) | 16sar-F* † | CGC CTG TTT ATC AAA AAC AT | Palumbi et al. [56] |

| 16sbr-H* † | CCG GTC TGA ACT CAG ATC ACG T | Palumbi et al. [56] | |

| rbcL (on kleptoplasts and chloroplasts) | rbc1* † | CCA MAA ACW GAA ACW AAA GC | Hanyuda et al. [57] |

| U3-2* † | TCT TTC CAA ACT TCA CAA GC | Hanyuda et al. [57] | |

| 2 U† | TTG GTW ACW GAA CCT TCT TC | Hanyuda et al. [57] | |

| rbc5† | GCT TGW GMT TTR TAR ATW GCT TC | Hanyuda et al. [57] | |

| trbcL-F‡ | CTK GCD GYD YTT MGD ATG ACA C | This study | |

| trbcL-R‡ | MRG CWA RWG AAC GTC CTT CAT T | This study |

Primers used for PCR and sequencing of mitochondrial 16S rDNA and kleptoplast (chloroplast) rbcL genes, and for T-RFLP analysis of rbcL .

Primers for PCR.

Primers for sequencing.

Primer for T-RFLP.

The PCR mixture (50 µl) contained 5 µl of 10× Ex Taq Buffer (Takara Bio, Otsu, Japan), 4 µl of dNTP mixture (10 mM), 0.2 µl of TaKaRa Ex Taq (Takara Bio), 1 µl of the template DNA, and 39.8 µl of H2O. The thermal cycle was completed under the following conditions: initial denaturation at 96°C for 1 min followed by 35 cycles of 20 s at 96°C, 45 s at 50–55°C, and 1 min 45 s–2 min at 72°C. Amplicons of rbcL and mt16S rDNA were purified using a Wizard SV Gel and a PCR Clean-Up System (Promega, Heidelberg, Germany).

Purified amplicons of the rbcL genes were cloned using a TOPO TA Cloning Kit with Top 10 E. coli (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The insert size was checked with PCR, and amplicons with the expected size were purified by Sap/ExoI digestion. The sequencing reactions were performed using a BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) with the primers used for the PCR experiments and two internal primers (Table 1). The nucleotide sequences were determined with an ABI 3130xl Sequencer (Applied Biosystems). If the genetic distance between two or more rbcL sequences was less than 0.001 in p-distance, those sequence differences were considered as a PCR error and the minor different sequences were excluded from further analyses. Using the Blastn search and tree reconstruction on partial sequences [28], two chimera sequences were detected and excluded from further processing.

Purified amplicons of sea slug mt16S rDNA were directly sequenced with the primers used for the PCR experiments (Table 1). The sequencing was performed as described above.

Sampling and genetic analysis of algae

In order to expand the reference dataset of rbcL sequences of potential source algae from the study region, species belonging to the siphonous green algal order Bryopsidales were collected at Tenija, Bise (26°42′N 127°52′E), Seragaki (26°30′N 127°52′E), and Maeda (26°26′N 127°45′E) in Okinawa, at Faro de San Rafael (24°18′N 110°20′W) in Mexico, and at Asuncion Island (19°41′N 145°23′E) in the Mariana Islands. No permission was required for sample collection. The samples were fixed in 99% ethanol and kept at −30°C until use. The species sampled were Rhipidosiphon lewmanomontiae, Rhipidosiphon sp., Caulerpa subserrata, Halimeda borneensis, Chlorodesmis fastigiata, and Poropsis sp.

We pressed voucher specimens from part of each sample and deposited them in the Herbarium of the Coastal Branch of the Natural History Museum and Institute, Chiba (CMNH) (specimen numbers CMNH-BA-6809–6816), Japan, or in the Ghent Herbarium, Belgium (G.008 and HV1774). The DNA was extracted from the ethanol-fixed algal tissues with a DNeasy blood and tissue kit (Qiagen), an Isoplant kit (Nippon Gene, Toyama, Japan), or a DNeasy plant kit (Qiagen). Then, algal rbcL genes were amplified by PCR and directly sequenced with the same primers used for PCR (Table 1) as described above.

Phylogenetic analyses of kleptoplast rbcL

The rbcL sequences obtained from P. ocellatus and algae were aligned with those of Bryopsidales and Dasycladales species in the DNA Data Bank of Japan (DDBJ) using MAFFT version 6.818b [29] with the “—auto” option. Ambiguously aligned sites were removed automatically using trimAl version 1.2 [30] with the “-automated1” option. The multiple sequence alignment finally showed 1254 positions. Phylogenetic analyses were performed with MEGA5 [31] for the neighbor-joining (NJ) method, and with RAxML version 7.2.8 [32] for the maximum likelihood (ML) method. For the NJ method, the maximum composite likelihood method for nucleotide sequences [33] was employed. Kakusan4 [34] was used to select the appropriate model of nucleotide evolution for ML analysis, and the general time-reversible model [35] incorporating among-site rate variation approximated by a discrete gamma distribution with 4 categories (GTR+Γ) was chosen. The nonparametric bootstrap was used to examine the robustness of phylogenetic relationships (1000 pseudoreplicates for NJ and 300 for ML).

Terminal restriction fragment-length polymorphism analysis of rbcL from P. ocellatus

We performed terminal restriction fragment-length polymorphism (T-RFLP) analysis [36] to assess the diversity of kleptoplasts in the sea slugs and the seasonality of their relative abundance. To avoid the biases of the amplification efficiency of PCR due to the high/low matching of the primers, we newly designed nested consensus primers for T-RFLP based on the rbcL sequences obtained (Table 1). The primers were designed to amplify the fragment including a specific restriction site for distinguishing different source algae of the kleptoplasts. We digested the rbcL regions obtained from P. ocellatus with various restriction enzymes in silico using TRiFLe [37]. TaiI (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) was found to be the most suitable to identify the multiple-source algal species of kleptoplasts (Table 2).

Table 2. In silico T-RF lengths of rbcL sequences.

| Clade in Figure 1 | Predicted T-RF length in silico (bp) | T-RFLP-category§ | Abbreviation (clade) |

| Clade A (Proposis spp.)* | 306 | Proposis spp./Halimeda borneensis | Prsp/Habo (A/D) |

| Clade B (Rhipidosiphon lewmanomontiae) | 331 | Rhipidosiphon lewmanomontiae | Rhle (B) |

| Clade C (Rhipidosiphon spp.) | 366 | Rhipidosiphon spp. | Rhsp (C) |

| Clade D (Halimeda borneensis)* | 306 | Proposis spp./Halimeda borneensis | Prsp/Habo (A/D) |

| Clade E (Halimedineae spp. 1)† | 138 | Halimedineae spp. 1/Rhipiliaceae spp. | Hasp1/Risp (E/G) |

| Clade F (Caulerpella spp.)‡ | 191/291 | Caulerpella spp. | Casp (F) |

| Clade G (Rhipiliaceae spp.)† | 138 | Halimedineae spp. 1/Rhipiliaceae spp. | Hasp1/Risp (E/G) |

| Clade H (Halimedineae spp. 2) | 260 | Halimedineae spp. 2 | Hasp2 (H) |

T-RF lengths of Proposis spp. and Halimeda borneensis were the same and indistinguishable.

T-RF lengths of Halimedineae spp. 1 and Rhipiliaceae spp. were identical and indistinguishable.

Caulerpella spp. was composed of two subtypes having two distinct T-RFs (191 and 291 bp, respectively).

The rbcL fragments were amplified from the DNA templates of P. ocellatus by PCR with the fluoresceinated primer trbcL-F and the nonfluoresceinated primer trbcL-R (Table 1). Thermal cycling was performed under the following conditions: initial denaturation at 96°C for 1 min followed by 35 cycles of 20 s at 96°C, 45 s at 57°C, and 1 min at 72°C. The composition of the PCR mixture was the same as that for clone sequencing. Amplicons in the reaction mixtures (50 µl) were purified with a Wizard SV Gel and PCR Clean-Up System (Promega, Madison, WI). The purified amplicons were digested with 0.5 µl of FastDigest TaiI (Fermentas, Vilnius, Lithuania) and then 0.5 µl of 10× FastDigest Buffer (Fermentas) in a total volume of 5 µl at 65°C for 15 min. The digestion product was mixed with 9 µl of Hi-Di formamide (Applied Biosystems) and 0.5 µl of GS 1200 (Liz) (Applied Biosystems) and then denatured by heating at 95°C for 2 min. The mixture was immediately chilled on ice and then electrophoresed with an ABI 3730xl Sequencer (Applied Biosystems).

T-RFLP profiles were analyzed using GeneMapper ver. 3.7 (Applied Biosystems). The internal size standards in electrophoresis gave an indication of the length of the terminal restriction fragments (T-RFs) obtained. Based on the different lengths (base pairs [bp]) of T-RFs, the source algae of the kleptoplasts were distinguished. Relative amounts of the respective rbcL sequences were estimated from the heights of T-RF peaks in T-RFLP electropherograms [36], [38].

Chromatograms with high-quality value (QV>75) were selected for further analyses. Fragments smaller than 100 bp and larger than 1200 bp were considered noise and excluded from further analyses. Each T-RF was identified by matching to the in silico digestion lengths of rbcL sequences from kleptoplasts (Table 2). The relative abundance was calculated from relative peak heights using the formula RA (%) = HT-RF/Htotal*100 (where RA is relative abundance, HT-RF is the peak height of a specific T-RF, and Htotal is the total of all T-RF peak heights in each chromatogram). The statistical significance of the differences in rbcL abundance between seasonally collected samples was assessed with the permuted Brunner-Munzel test [39] implemented in the “lawstat” package for “R” [40].

Amino acid nitrogen isotopic analysis

To estimate the trophic position of the sea slugs under natural conditions and during starvation, we used amino acid nitrogen isotopic analysis [24], [25]. The individuals of P. ocellatus for the amino acid nitrogen isotopic analysis were collected off Toguchi, Okinawa, Japan (26°21′N 127°44′E). No permission was required for sample collection. About 50 individuals were collected on 27 April 2010. For transport to the laboratory in Kanagawa, Japan, they were kept alive in artificial seawater (Rhotomarine, Rei-Sea, Tokyo, Japan) at room temperature for 3 days without lighting. Three healthy individuals were randomly selected and dissected, and parapodial tissues were frozen and kept in liquid nitrogen as wild samples. The samples for starvation were collected on 8 April 2008 (about 50 individuals) and incubated in an aquarium filled with artificial seawater not containing macroalgae at 24°C under light (13 µmol photons m−2 s−1) with day–night (14-h light/10-h dark) rhythms. After incubation for 156 days (about 5 months), 3 individuals were randomly selected and dissected. Their parapodial tissues were also frozen and kept in liquid nitrogen until analysis.

The nitrogen isotope analysis of amino acids was performed according to the method of Chikaraishi et al. [25]. Part of the frozen parapodial tissue of each P. ocellatus individual was hydrolyzed in 12N HCl at 100°C. The hydrolysate was washed with n-hexane/dichloromethane (6∶5, v/v) to remove any hydrophobic constituents. After derivatization with thionyl chloride/2-propanol (1∶4, v/v) and subsequently with pivaloyl chloride/dichloromethane (1∶4, v/v), the derivatives of the amino acids were extracted with n-hexane/dichloromethane (6∶5, v/v). The nitrogen isotopic composition of each amino acid was determined by gas chromatography/combustion/isotope ratio mass spectrometry using a Delta plus XP isotope ratio mass spectrometer (Thermo Finnigan MAT, Bremen, Germany) coupled to an 6890N gas chromatograph (Agilent Technologies, Massy, France) via combustion and reduction furnaces. Nitrogen isotopic compositions were expressed in δ-notation against atmospheric N2 (air). The trophic position of the organism was calculated from the nitrogen isotopic ratio in glutamic acid and phenylalanine (TPGlu/Phe value) with the formula TPGlu/Phe = (δ15NGlu−δ15NPhe−3.4)/7.6+1 [24].

We also determined the TPGlu/Phe value of a giant clam, Tridacna crocea, harboring a symbiotic dinoflagellate, zooxanthellae (Symbiodinium spp.) [41], and of an identified kleptoplast source alga, R. lewmanomontiae. Three individuals of T. crocea were collected off Sesokojima, Okinawa (26°38′N 127°52′E) on 19 November 2011. After 3 days of incubation without feeding and light for transport to the laboratory, the mantle tissues containing zooxanthellae and adductor muscles without zooxanthellae were dissected from each individual. The adductor muscles were analyzed using the same method as for the tissue of P. ocellatus. To isolate zooxanthellae, mantles of each individual were cut into pieces, homogenized with a polytron-type homogenizer (T-10 basic homogenizer, IKA, Staufen, Germany) with 20 ml of artificial seawater, and centrifuged at 750×g for 3 min [42]. After decantation of the supernatant, the pellet was suspended with 20 ml of artificial seawater. The suspension was filtered through a 20-µm mesh nylon cloth to remove host tissue debris and washed two times with 20 ml of artificial seawater. Pelleted zooxanthellae were used for the amino acid nitrogen isotopic analysis. A thallus of R. lewmanomontiae was collected at the same site with P. ocellatus (off Toguchi, Okinawa) on 27 April 2010 and its δ15N was analyzed as described above.

Results

Identification of P. ocellatus kleptoplasts

To confirm the genetic homogeneity of P. ocellatus collected and identify the source algae of kleptoplasts, we sequenced their mt16S rDNA and rbcL. The sequences of mt16S rDNA fragments [443 bp: DNA Data Bank of Japan (DDBJ) accession number, AB700359] were identical among all examined P. ocellatus individuals collected off Tenija, Okinawa, Japan, suggesting that all samples belonged to the same species.

By clone sequencing, we obtained 209 rbcL sequences of kleptoplasts from 7 individuals of P. ocellatus collected in 2005 (Table 3). After unifying highly similar sequences (p-distance<0.001), 59 sequences were used for subsequent analyses (DDBJ accession numbers, AB619256–AB619314).

Table 3. Number of clones obtained from kleptoplast rbcL clone sequences.

| Corresponding clades (in Figures 1 and 2) of clones | Total | ||||||||

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | ||

| ID of the individual (month of collection) | |||||||||

| Po-2005-A (Apr.) | 1 | - | - | - | 7 | - | - | 8 | 16 |

| Po-2005-B (May) | 18 | - | 1 | - | 2 | - | - | - | 21 |

| Po-2005-C (June) | 7 | 5 | 4 | - | - | 3 | - | - | 19 |

| Po-2005-D (Aug.) | 10 | 3 | 4 | - | - | 7 | - | - | 24 |

| Po-2005-E (Aug.) | 82 | - | - | 1 | - | - | 5 | 2 | 90 |

| Po-2005-F (Sept.) | 11 | - | - | - | - | 4 | - | - | 15 |

| Po-2005-G (Nov.) | 13 | - | 4 | 1 | - | 6 | - | - | 24 |

| Total number of clones | 142 | 8 | 13 | 2 | 9 | 20 | 5 | 10 | 209 |

Number of clones obtained in kleptoplast rbcL clone sequencing from each of 7 Plakobranchus ocellatus individuals. The source algae were identified from the phylogenetic analysis (Figure 1).

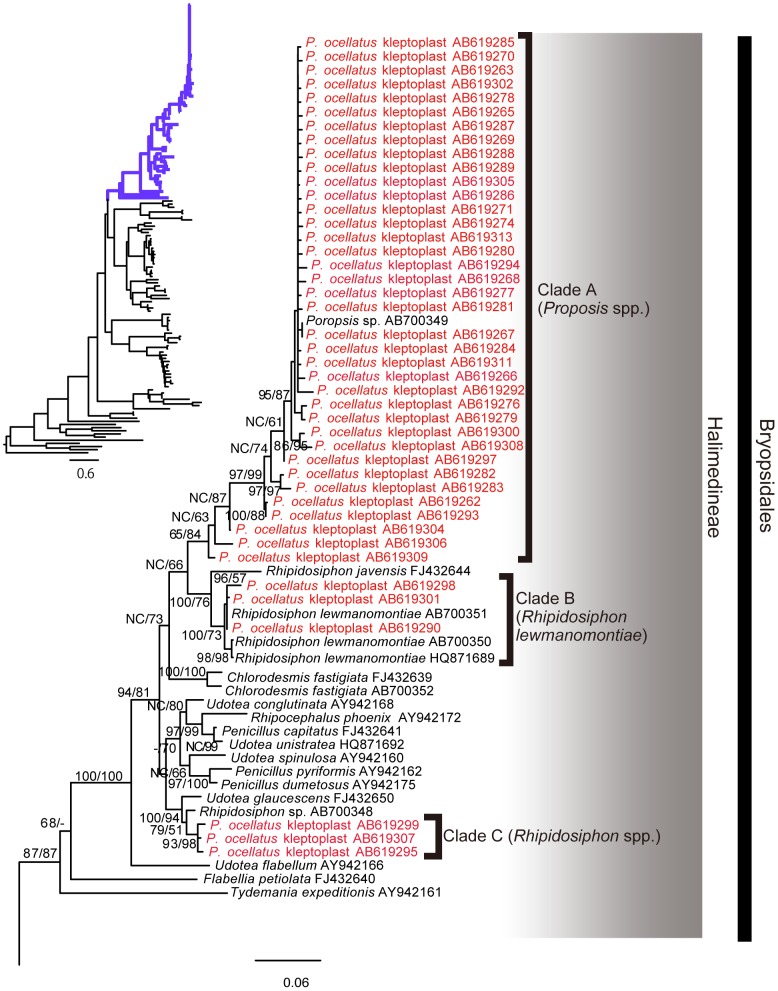

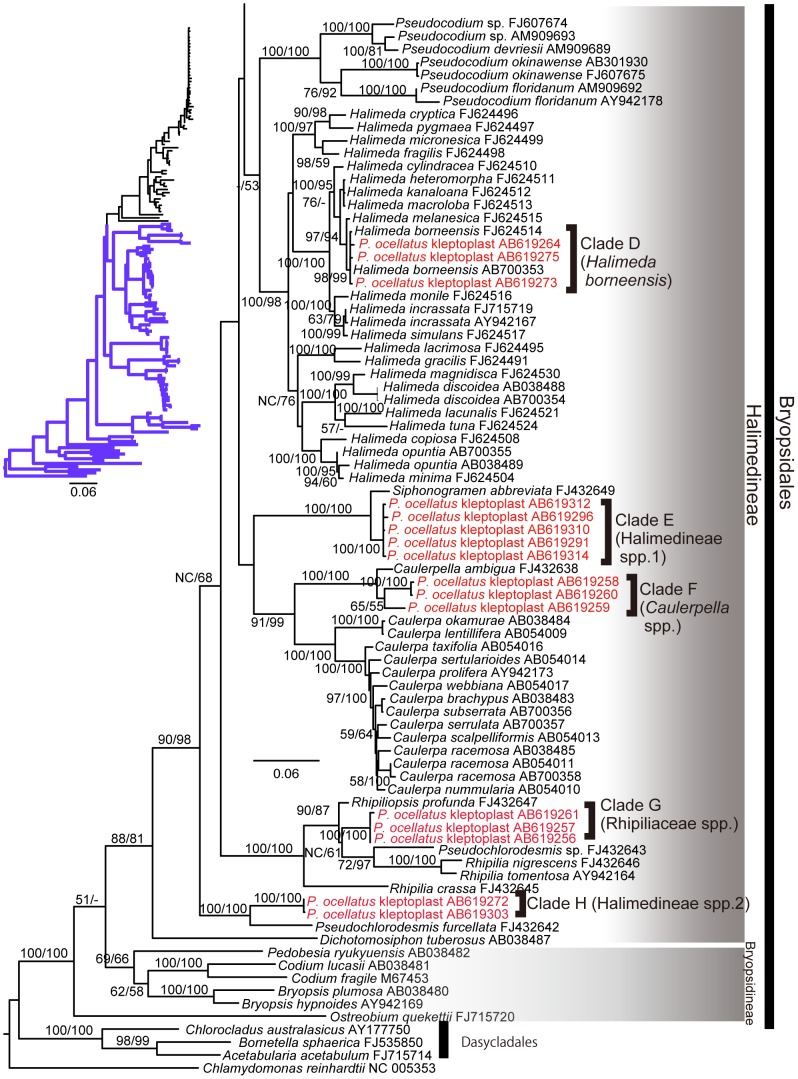

Blastn analyses showed that the kleptoplast rbcL sequences were the most similar to those from green algae belonging to the suborder Halimedineae (order Bryopsidales). In the phylogenetic tree (Figures 1 and 2), the kleptoplast sequences did not form a monophyletic clade but were divided into eight clades within the Halimedineae (clades A–H in Figures 1 and 2). Clade B sequence AB619290 was identical to R. lewmanomontiae from Tenija (AB700351). Clade D corresponded to reference sequences of H. borneensis (FJ624514 and AB700353). The remaining 6 clades of kleptoplasts (A, C, E, F, G, H) could not be identified at the species level and were assigned to higher taxa. Clade A clustered with Poropsis sp., clade C with Rhipidosiphon sp., clade F with the genus Caulerpella, and clade G with the family Rhipiliaceae. Familial relationships were unclear for clades E and H, but they both belong to the higher taxon Halimedineae. For convenience, the source algae with such imperfect identifications are indicated with a higher taxon name+spp. (e.g., Rhipiliaceae spp.).

Figure 1. Phylogenetic tree based on rbcL sequences.

Maximum likelihood (ML) phylogeny of the class Ulvophyceae based on 1254 nucleotide positions of the chloroplast-encoded rbcL gene. The phylogram of the entire tree on the upper left is colored to match the inset. Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (class Chlorophyceae) was chosen as the outgroup. Red, rbcL sequences from P. ocellatus. Black, algal rbcL sequences. Bootstrap support (BS) values >50% are provided at the nodes (neighbor-joining/ML). “-“, BS <50%; “NC”, nonconsensus node that was not observed in the neighbor-joining tree.

Figure 2. Phylogenetic tree based on rbcL sequences (continued).

Based on the rbcL sequences cloned from the 7 individuals, it was already clear that individual sea slugs contained kleptoplasts from multiple source species. As shown in Table 3, no single individual had only one type of kleptoplast. In most cases, kleptoplasts from 3 or 4 algal species were present in P. ocellatus individuals.

Seasonality of P. ocellatus kleptoplasts

To examine whether the composition of kleptoplasts changed over time, T-RFLP analysis of rbcL with TaiI digestion was performed. Halimedineae spp. 1 (clade E) and Rhipiliaceae spp. (clade G) could not be distinguished in this analysis because their predicted T-RF lengths were identical at 138 bp (Table 2). They are hereafter referred to as “Hasp1/Risp (clade E/G).” The T-RF of Poropsis spp. (clade A) could not be differentiated from that of H. borneensis (clade D) (T-RF length = 306 bp, Table 2), and they are referred to as “Prsp/Habo (clade A/D).” The heights of those T-RF peaks were regarded as the sum of the respective two algal source clades (Table 2).

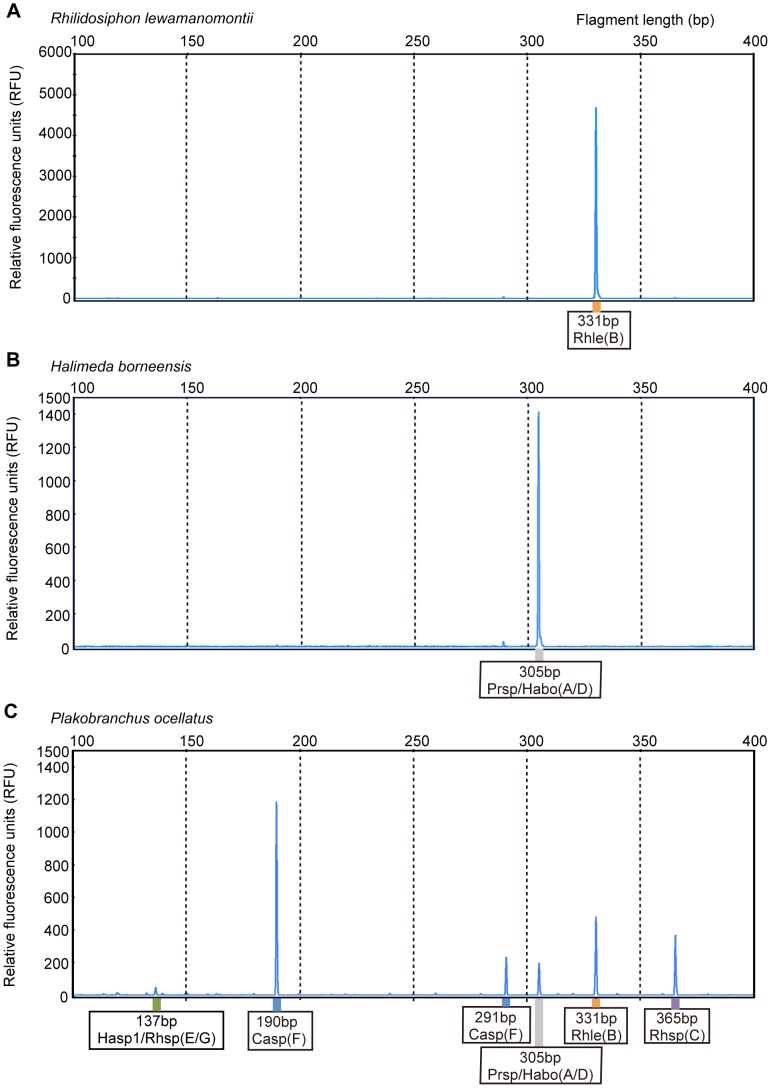

To establish the applicability of in silico T-RF predictions in actual T-RFLP analysis, we compared the predicted T-RF fragment lengths with those of PCR-amplified rbcL fragments from two algae, H. borneensis and R. lewmanomontiae. We obtained a single T-RF peak in each algal species, and its T-RF length was identical with that predicted in silico (H. borneensis = 306 bp and R. lewmanomontiae = 331 bp) (Table 2, Figure 3A, B).

Figure 3. Electropherograms of T-RFLP analysis.

T-RFLP electropherograms from (A) Rhipidosiphon lewmanomontiae, (B) Halimeda borneensis, and (C) a single individual of Plakobranchus ocellatus (sample no. Ploc051113A). Fragment lengths and corresponding source algae are shown in the box under the peak. Only a single peak with a length identical to that predicted by in silico T-RFLP was obtained from each algal individual (Table 2). The electropherogram from the sea slug (C) showed multiple peaks corresponding to those of in silico T-RFLP of the kleptoplast source algae (Table 2).

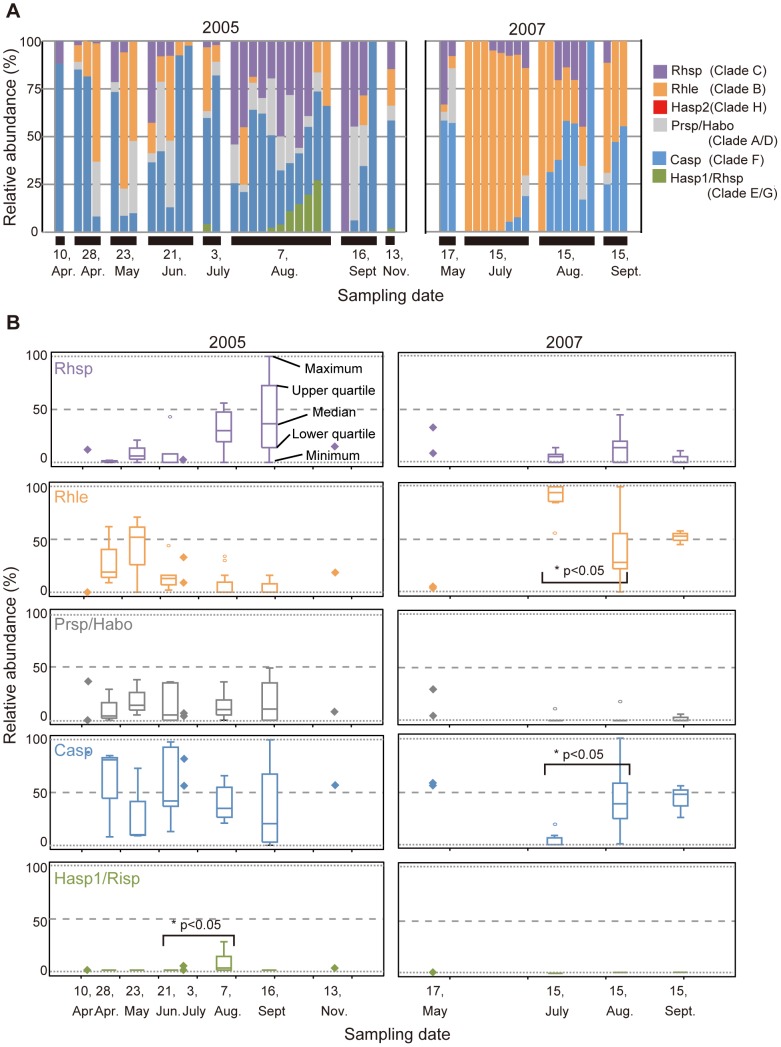

High-quality T-RFLP electropherograms (quality value >75) were obtained from 30 individuals of P. ocellatus collected in 2005 and from 20 collected in 2007 (Figure 4A). One to five peaks were found in each P. ocellatus individual (Figures 3C and 4A, Table S1). Except for the peak corresponding to Halimedineae spp. 2 (clade H) (260 bp), all predicted restriction profiles were recovered. Forty-four out of 50 individuals of P. ocellatus showed multiple T-RF peaks (28 individuals in 2005 and 16 in 2007) (Figure 4A, Table S1).

Figure 4. Time series of rbcL sequence composition in Plakobranchus ocellatus.

(A) Relative abundance of respective rbcL in individuals of Plakobranchus ocellatus collected monthly in 2005 and 2007. Source algae of kleptoplasts are shown by abbreviations of the clades (Table 2). (B) Tukey's boxplots of the relative abundance of rbcL sequences. Data points of fewer than three individuals of P. ocellatus are shown as diamonds. The brackets with “*” indicate a significant difference of the percentage value in the permuted Brunner-Munzel test. The value beside the symbol “*” indicates p-value.

Assuming that the genome copy number in the chloroplasts did not change before and after sequestration, the relative abundance of rbcLs was used to estimate that of the corresponding kleptoplasts. As shown by the boxplots in Figure 4B, the relative abundance of kleptoplasts showed marked seasonal changes. Some of the observed changes occurred over a relatively short time-span. For example, in 2005, the abundance of Hasp1/Risp (clade E/G) in August was significantly higher than that in June (p-value = 0.025) (Figure 4B). Similarly, in 2007, the percentage of Caulerpella spp. (clade F) significantly increased from July to August (p-value = 0.010), while that of R. lewmanomontiae (clade B) significantly decreased in the same period (p-value = 0.020) (Figure 4B). In 2005, clear changes in abundance were also observed for Rhipidosiphon spp. (clade C), R. lewmanomontiae (clade B), and Hasp1/Risp (clade E/G) but these were not significant in the permuted Brunner-Munzel test (p-value = 0.097, 0.571, and 0.102, respectively) (Figure 4B).

Trophic position of P. ocellatus

To estimate the trophic position of P. ocellatus, the δ15N values of glutamic acid (δ15NGlu) and phenylalanine (δ15NPhe) of the freshly collected and starved samples of P. ocellatus were measured, and TPGlu/Phe values were calculated. The mean TPGlu/Phe value of 3 freshly collected P. ocellatus individuals was 1.9±0.1 (mean ± “1σ for the TP values,” n = 3) (Table 4). On the other hand, the mean TPGlu/Phe values of P. ocellatus that had been starved under light for about 5 months (156 days) was 1.3±0.1 (n = 3) (Table 4). The TPGlu/Phe value of R. lewmanomontiae, which was a source alga of kleptoplasts in P. ocellatus, was 1.0 (n = 1). The mean TPGlu/Phe value of T. crocea adductor muscle was 2.0±0.1 (n = 3), and that of zooxanthellae isolated from T. crocea mantle was 0.9±0.0 (n = 3).

Table 4. δ15N values of amino acids and estimated trophic positions of Plakobranchus ocellatus, the alga Rhipidosiphon lewmanomontiae, and the giant clam Tridacna crocea.

| Specimen | Number of specimens | Averaged δ15N value§ (SD) | Trophic position# | |

| Glutamic acid | Phenylalanine | |||

| Plakobranchus ocellatus | ||||

| Freshly collected* (Apr. 2010) | 3 | 17.4 (0.9) | 7.3 (1.3) | 1.9 (0.08) |

| Starved† (Apr.–Nov. 2008) | 3 | 20.0 (0.5) | 14.4 (0.9) | 1.3 (0.07) |

| Rhipidosiphon lewmanomontiae (Apr. 2010) | 1 | 12.3 | 8.8 | 1.0 |

| Tridacna crocea (Nov. 2011) | ||||

| Adductor muscle | 3 | 16.1 (0.6) | 5.5 (0.1) | 2.0 (0.07) |

| Zooxanthellae‡ | 3 | 8.2 (0.4) | 5.3 (0.1) | 0.9 (0.04) |

Collected off Toguchi, Okinawa, Japan.

Starved for 156 days (5 months) in a laboratory aquarium after collection off Toguchi.

Symbiodinium spp. isolated from the mantle of T. crocea.

‰, relative to air.

Trophic position (TPGlu/Phe) = (δ15NGlu−δ15NPhe−3.4)/7.6+1.

Discussion

By combining different methods, our results offer several new insights into the ecology of functional kleptoplasty in P. ocellatus. Because unincubated wild individuals were studied, the results shed light on the natural state of this sea slug species.

Multiple algal sources of kleptoplasts in P. ocellatus

The phylogenetic analyses of the chloroplast-encoded rbcL gene identified at least 8 algal sources of kleptoplasts in P. ocellatus (Figure 1). This number exceeds the estimates from previous laboratory feeding experiments on P. ocellatus [18], [20] Our data demonstrate that P. ocellatus has one of the broadest food algal spectra in the Sacoglossa, including at least 8 species in 5 different algal genera [7]. The multiplicity of kleptoplasts in individual sea slug specimens also confirms that individuals have multiple food sources. This multiplicity of kleptoplasts was first reported in a sacoglossan, Elysia clarki (2–4 species) [9], and also recently suggested in P. ocellatus [17]. These findings strongly suggest that, in the natural setting, the sea slugs feed on several species and retain their chloroplasts in digestive gland cells.

A common conclusion of our work and previous feeding studies on P. ocellatus [7], [18], [20] is that their food/source algae are all siphonous green algae of the order Bryopsidales. The genus Caulerpella, which was identified as a food source in a previous study [20], was shown to be a major contributor to the kleptoplast pool. On the other hand, we did not detect 3 algal species that were eaten by P. ocellatus in a laboratory setting in previous studies: C. hildebrandtii (Udoteaceae); Bryopsis sp.; and R. javensis [18], [20]. Such discordance may be because the algae in question are not preferred by P. ocellatus in their natural habitats, or because the algae are ingested but their chloroplasts are not retained. For some of the algal species involved, misidentifications could also lead to the mismatch. For example, Rhipidosiphon is a genus of diminutive, fan-shaped algae in which there are several morphologically similar but genetically distinct species (Verbruggen, unpublished results), and kleptoplast clade C may originate from algae that closely resemble R. javensis. Similarly, it is possible that in the previous studies the source algae belonging to clade A (genus Poropsis) could have been misidentified as C. hildebrandtii. Because these taxa are anatomically very similar, and because the genus Poropsis is little known and not commonly included in taxonomic reference works, it may have been regarded as C. hildebrandtii in previous studies.

Our kleptoplast survey also revealed several new food algae of P. ocellatus. Among them are R. lewmanomontiae (clade B), H. borneensis (clade D), Rhipiliaceae spp. (clade G), and potentially Rhipidosiphon spp. (clade B). In addition to these taxa, we found kleptoplasts of two lineages that could not be readily assigned to a family (Halimedineae spp. 1 and spp. 2). The most closely related rbcL sequences of these two clades are Pseudochlorodesmis species (Figure 1). The diminutive siphon of Pseudochlorodesmis, if branched at all, does so only a few times [43]. Because the algae rarely exceed a few millimeters in length, it should not come as a surprise that they may have been overlooked in previous studies. The observed ulvophyceaen macroalgae in sampling sites are listed in Table S3.

An interesting observation is that P. ocellatus do not seem to discriminate among food sources based on size. Among the sources of kleptoplasts are some larger seaweeds such as H. borneensis (10 cm) and R. lewmanomontiae (3 cm) as well as several millimeter-scale taxa (Pseudochlorodesmis, Caulerpella). One commonality between these algae is that they all belong to suborder Halimedineae of the order Bryopsidales (Figure 1) [44], which is consistent with the hypothesis on the relationships between the radular tooth shape and food algal cell wall components [45]. The radular tooth of P. ocellatus has a triangular shape suitable for puncturing a hole in the halimedineaen cell wall, which is composed of xylan [45], [46], after which the cytoplasm can be ingested.

Changing annual kleptoplast composition

T-RFLP analysis showed that the kleptoplast rbcL composition of the sea slugs changed considerably from month to month. Because kleptoplasts have not been observed to divide [2], [17], these changes must result from the replacement of kleptoplasts with newly obtained chloroplasts by feeding, different spans of longevity among kleptoplasts derived from various source algae, and/or differential kleptoplast DNA replication (multimerization) rates [47], [48] due to those source algae.

Different spans of longevity and change in chloroplast genome multimerizations of the kleptoplasts would leave a specific imprint on the kleptoplast composition over time, i.e., the recovered kleptoplast composition would remain the same but their relative abundance should increase/decrease gradually over time. Our results do not suggest such a pattern but rather suggest that large, apparently stochastic changes occur in kleptoplast composition. Although we cannot entirely exclude the possibility that P. ocellatus individuals immigrated into the population at the collection sites, previous studies suggested that P. ocellatus breed in a restricted season in spring and rarely migrate as adults [18], [49]. Therefore, the hypothesis that kleptoplasts are replaced with newly obtained chloroplasts from ingested algae appears to be the most plausible explanation for our results. Although the seasonal change in the algal community may affect the kleptoplast compositions in P. ocellatus, this point remains to be studied in future.

Trophic position of P. ocellatus

Assuming an error in the TPGlu/Phe value (i.e., 1σ = 0.12) [24], the values of wild P. ocellatus (mean TPGlu/Phe value = 1.9) were identical to the trophic position of algivorous organisms, i.e., primary consumers (Table 4, S2). These results clearly indicate that, under natural circumstances, P. ocellatus individuals mainly obtain amino acids by digestion of ingested algae. This is in stark contrast to P. ocellatus individuals that had been starved for 5 months and had a TPGlu/Phe value of 1.3, which is intermediate between values typical of phototrophic organisms (primary producers) and algivores (primary consumers).

These results suggest that kleptoplasts of P. ocellatus could produce amino acids, for which the TPGlu/Phe value would be 1.0, similar to that of primary producers. The production of amino acids from inorganic nitrogen was also reported in kleptoplasts of E. viridis in a tracer experiment using 15N-inorganic nitrogen [14]. Teugels and coworkers have proposed that kleptoplasts synthesize glutamic acid from ammonium derived from seawater or made from nitrate and/or urea, and that other amino acids are synthesized from glutamic acid [14]. It is not clear whether the enzymes of these pathways remain active in the kleptoplasts [17] or whether their genes are expressed in the host animal nucleus to which they were transferred from the algal nuclear genome [50]. When the amount of amino acids from the digestion of algae is much larger than that from kleptoplasts, the TPGlu/Phe value would become 2.0. Accordingly, the observed TPGlu/Phe values (i.e., 1.3±0.1) for cultured individuals imply some significant contribution of the kleptoplast-produced amino acids to P. ocellatus during starvation.

The giant clam T. crocea harbors zooxanthellae, which contribute significantly to the host nutrition, but it also feeds on free-living plankters [51]. Previous studies showed that the zooxanthellae secrete a photosynthate, glycerol or glucose, in the mantle tissue [42], [52], [53] but the zooxanthellae are also digested in the stomach [54], [55]. Those previous results suggested that essential amino acids are derived from the digestion of zooxanthellae and plankters. The TPGlu/Phe value of the giant clam T. crocea was 2.0, which is in agreement with previous results [54], [55] showing that T. crocea gain amino acids by the digestion of zooxanthellae in symbiotic relationships as well as the digestion of free-living plankters. The data together with those of natural and starved individuals suggest that wild P. ocellatus obtain amino acids mainly from heterotrophic digestion of algae as in the case of T. crocea, while starved individuals obtain significant amounts of amino acids from photosynthetic production in kleptoplasts.

Feeding of P. ocellatus under natural conditions

The present results indicate that P. ocellatus gain kleptoplasts from multiple algal species, that each individual harbors a heterogeneous population of kleptoplasts from multiple algal species, that the kleptoplast composition changes with time, and that the sea slugs mainly gain amino acids by digesting ingested algae in nature, although kleptoplasts are probably capable of producing amino acids. These combined findings suggest that wild P. ocellatus repeatedly feed on siphonous green algae and acquire new kleptoplasts when there is sufficient algal biomass to feed the P. ocellatus population. The ecological role of functional kleptoplasty has been hypothesized to be a nutrition resource during periods of food insecurity [6], [15]. The photosynthetic activity of kleptoplasts in starved P. ocellatus is reduced by about 10% per month [10]. Replenishing kleptoplasts equivalent to the photosynthetic activity lost is necessary to sustain the required level of photosynthetic activity.

Although P. ocellatus is capable of retaining kleptoplasts for up to 10 months, our results indicate that the nutritional contribution of kleptoplasts may be insufficient even in a natural habitat where food algae are plentiful. In other sacoglossan species such as Elysia timida, E. viridis, and Thuridilla carlsoni, the nutritional contribution of functional kleptoplasts may be even less, because the photosynthetic activity of their kleptoplasts is less and retention periods are shorter than in P. ocellatus [10]. The ecological role of kleptoplasts under natural conditions when food is abundant remains unclear. Functional kleptoplasty may reduce the algal feeding and the energy cost to ingest their calcified thallus [6]. Our present study showed that the nutritional yield from kleptoplasts does not exceed that from food digestion but suggested that they provide an energy source (e.g., sugars) and essential nutrients (e.g., amino acids) under starved conditions. The TPGlu/Phe value of 1.3 during starvation suggests that the contribution of kleptoplasts to amino acid synthesis is much greater than that of autophagic digestion of reserved amino acids and proteins, which would increase the TPGlu/Phe value. It has been proposed that the function of kleptoplasts may be to complement nutrients under starved conditions [6]. Our present results support this hypothesis.

Although adult P. ocellatus are thought to be nourished by the photosynthetic activity of functional kleptoplasty, the present study suggests that the sea slug continually feeds on siphonous green macroalgae in its natural habitat and that digested algae are the major source of nutrition, while kleptoplast photosynthesis plays a very minor role. Further studies on the feeding behavior, photosynthetic activity, and nutritional contribution of kleptoplasts in P. ocellatus are necessary to understand the ecological role of the functional kleptoplasty of this species.

Supporting Information

Overviews of Plankobranchus ocellatus . (A) Dorsal views of a freshly collected intact P. ocellatus individual. (B) An anesthetized individual with spread parapodia. The tissue region in the red square was dissected and used for DNA extraction.

(TIF)

Percentage abundance of rbcL sequences from source algae in P. ocellatus *.

(XLS)

(XLS)

(XLS)

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Rie Nakano, Dr. Tohru Iseto, Dr. Seiji Takegata, and all staff in E. Hirose's laboratory for their support in the field; Dr. Tom Schils for providing some of the algal specimens; Dr. Naohiko Ohkouchi and Ms. Yoko Sasaki for their advice and help on the nitrogen isotopic study; and Dr. Dhugal Lindsay for his advice on writing the manuscript.

Funding Statement

The present research was supported by a grant from the Mikimoto Fund for Marine Ecology, a Grant-in-Aid for a Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Fellow (No. 20234567 to T. Maeda), a grant from the Research Foundation Flanders, a grant from the Australian Research Council (FT110100585 to H. Verbruggen), and a grant from the Okinawa Intellectual Cluster Program (to T. Maruyama). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Kawaguti S, Yamasu T (1965) Electron microscopy on the symbiosis between an elysioid gastropod and chloroplasts of a green alga. Biol J Okayama Univ 11: 57–65. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rumpho M, Dastoor F, Manhart J, Lee J (2007) The kleptoplast. In: The structure and function of plastids. Wise R, Hoober JK, editors. Netherlands: Springer; 451–473. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Waugh GR, Clark KB (1986) Seasonal and geographic variation in chlorophyll level of Elysia tuca (Ascoglossa, Opisthobranchia). Mar Biol 92: 483–487. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Trench R, Greene R, Bystrom B (1969) Chloroplasts as functional organelles in animal tissues. J Cell Biol 42: 404–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Curtis NE, Pierce SK, Massey SE, Schwartz JA, Maugel TK (2007) Newly metamorphosed Elysia clarki juveniles feed on and sequester chloroplasts from algal species different from those utilized by adult slugs. Mar Biol 150: 797–806. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Williams SI, Walker DI (1999) Mesoherbivore-macroalgal interactions: Feeding ecology of sacoglossan sea slugs (Mollusca, Opisthobranchia) and their effects on their food algae. Mar Biol Annu Rev 37: 87–128. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Händeler K, Wägele H (2007) Preliminary study on molecular phylogeny of Sacoglossa and a compilation of their food organisms. Bonn Zool Beitr 55: 231–254. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Händeler K, Wägele H, Wahrmund UTE, Rüdinger M, Knoop V (2010) Slugs' last meals: molecular identification of sequestered chloroplasts from different algal origins in Sacoglossa (Opisthobranchia, Gastropoda). Mol Evol Resources 10: 968–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Curtis NE, Massey SE, Pierce SK (2006) The symbiotic chloroplasts in the sacoglossan Elysia clarki are from several algal species. Invertebr Biol 125: 336–345. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Evertsen J, Burghardt I, Johnsen G, Wägele H (2007) Retention of functional chloroplasts in some sacoglossans from the Indo-Pacific and Mediterranean. Mar Biol 151: 2159–2166. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Händeler K, Grzymbowski YP, Krug PJ, Wagele H (2009) Functional chloroplasts in metazoan cells—a unique evolutionary strategy in animal life. Front Zool 6: 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Greene R, Muscatine L (1972) Symbiosis in sacoglossan opisthobranchs: photosynthetic products of animal-chloroplast associations. Mar Biol 14: 253–259. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Trench R, Trench M, Muscatine L (1972) Symbiotic chloroplasts: their photosynthetic products and contribution to mucus synthesis in two marine slugs. Biol Bull 142: 335–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Teugels B, Bouillon S, Veuger B, Middelburg JJ, Koedam N (2008) Kleptoplasts mediate nitrogen acquisition in the sea slug Elysia viridis . Aquatic Biol 4: 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Clark KB, Jensen KR, Stirts HM (1990) Survey for functional kleptoplasty among West Atlantic Ascoglossa ( = Sacoglossa) (Mollusca, Opisthobranchia). Veliger 33: 339–345. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clark KB (1992) Plant-like animals and animal-like plants: symbiotic coevolution of ascoglossan ( = sacoglossan) molluscs, their algal prey, and algal plastids. In: Algae and symbioses: plants, animals, fungi, viruses, interactions explored. Reisser W, editor. Bristol, U.K.: Biopress Ltd. 515–530.

- 17. Wägele H, Deusch O, Händeler K, Martin R, Schmitt V, et al. (2011) Transcriptomic evidence that longevity of acquired plastids in the photosynthetic slugs Elysia timida and Plakobranchus ocellatus does not entail lateral transfer of algal nuclear genes. Mol Biol Evol 28: 699–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adachi A (1991) Morphological study on sacoglossan opisthobranch Plakobranchus spp. Master's thesis, University of the Ryukyus, Nishihara, Okinawa. [In Japanese].

- 19. Jensen KR (1992) Anatomy of some Indo-Pacific Elysiidae (Opisthobranchia, Sacoglossa ( = Ascoglossa)), with a discussion of the genetic division and phylogeny. J Mollusc Studies 58: 257–296. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dunlap MS (1975) Symbiosis between algal chloroplasts and the mollusc Plakobranchus ocellatus van Hasselt (Sacoglossa: Opisthobranchia). PhD thesis, University of Hawaii.

- 21. Greene RW (1970) Symbiosis in sacoglossan opisthobranchs: functional capacity of symbiotic chloroplasts. Mar Biol 7: 138–142. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lewis LA, McCourt RM (2004) Green algae and the origin of land plants. Am J Bot 91: 1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Green BR (2011) Chloroplast genomes of photosynthetic eukaryotes. Plant J 66: 34–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chikaraishi Y, Ogawa NO, Kashiyama Y, Takano Y, Suga H, et al. (2009) Determination of aquatic food-web structure based on compound-specific nitrogen isotopic composition of amino acids. Limnol Oceanogr Methods 7: 740–750. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chikaraishi Y, Kashiyamal Y, Ogawa NO, Kitazato H, Ohkouchi N (2007) Metabolic control of nitrogen isotope composition of amino acids in macroalgae and gastropods: implications for aquatic food web studies. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 342: 85–90. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hirose E (2005) Digestive system of the sacoglossan Plakobranchus ocellatus (Gastropoda: Opisthobranchia): Light- and electron-microscopic observations with remarks on chloroplast retention. Zool Sci 22: 905–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Trowbridge CD, Hirano YM, Hirano YJ (2011) Inventory of Japanese sacoglossan opisthobranchs: Historical review, current records, and unresolved issues. Am Malac Bull 29: 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hugenholtz P, Huber T (2003) Chimeric 16S rDNA sequences of diverse origin are accumulating in the public databases. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 53: 289–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Katoh K, Toh H (2010) Parallelization of the MAFFT multiple sequence alignment program. Bioinformatics 26: 1899–1900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Capella-Gutierrez S, Silla-Martinez JM, Gabaldon T (2009) trimAl: a tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics 25: 1972–1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, et al. (2011) MEGA5: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol 28: 2731–2739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Stamatakis A (2006) RAxML-VI-HPC: maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics 22: 2688–2690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tamura K, Nei M, Kumar S (2004) Prospects for inferring very large phylogenies by using the neighbor-joining method. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101: 11030–11035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tanabe AS (2011) Kakusan4 and Aminosan: two programs for comparing nonpartitioned, proportional and separate models for combined molecular phylogenetic analyses of multilocus sequence data. Mol Ecol Resources 11: 914–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rodriguez F, Oliver JL, Marin A, Medina JR (1990) The general stochastic model of nucleotide substitution. J Theor Biol 142: 485–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Liu WT, Marsh TL, Cheng H, Forney LJ (1997) Characterization of microbial diversity by determining terminal restriction fragment length polymorphisms of genes encoding 16S rRNA. Appl Environ Microbiol 63: 4516–4522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Junier P, Junier T, Witzel KP (2008) TRiFLe, a program for in silico terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis with user-defined sequence sets. Appl Environ Microbiol 74: 6452–6456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Osborn AM, Moore ERB, Timmis KN (2000) An evaluation of terminal-restriction fragment length polymorphism (T-RFLP) analysis for the study of microbial community structure and dynamics. Environ Microbiol 2: 39–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Neubert K, Brunner E (2007) A studentized permutation test for the non-parametric Behrens-Fisher problem. Comput Stat Data Anal 51: 5192–5204. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Team RDC (2009) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. http://www.R-project.org.

- 41. Yellowlees D, Rees TAV, Leggat W (2008) Metabolic interactions between algal symbionts and invertebrate hosts. Plant Cell Environ 31: 679–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ishikura M, Adachi K, Maruyama T (1999) Zooxanthellae release glucose in the tissue of a giant clam, Tridacna crocea . Mar Biol 133: 665–673. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Verbruggen H, Vlaeminck C, Sauvage T, Sherwood AR, Leliaert F, et al. (2009) Phylogenetic analysis of Pseudochlorodesmis strains reveals cryptic diversity above the family level in the siphonous green algae (Bryopsidales, Chlorophyta). J Phycol 45: 726–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Verbruggen H, Ashworth M, LoDuca ST, Vlaeminck C, Cocquyt E, et al. (2009) A multi-locus time-calibrated phylogeny of the siphonous green algae. Mol Phylogenet Evol 50: 642–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Jensen K (1993) Morphological adaptations and plasticity of radular teeth of the Sacoglossa ( = Ascoglossa) (Mollusca, Opisthobranchia) in relation to their food plants. Biol J Linnean Soc 48: 135–155. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hillis-Colinvaux L (1980) Ecology and taxonomy of Halimeda: primary producer of coral reefs. Adv Mar Biol 17: 1–327. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Deng XW, Wing RA, Gruissem W (1989) The chloroplast genome exists in multimeric forms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 86: 4156–4160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lü F, Xü W, Tian C, Wang G, Niu J, et al. (2011) The Bryopsis hypnoides plastid genome: multimeric forms and complete nucleotide sequence. PLoS one 6: e14663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kawaguti S, Yamamoto M, Yamasu T (1965) Electron microscopy on the symbiosis between blue-green algae and an Opisthobranch, Placobranchus . Proc Jpn Acad 41: 614–617. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Rumpho ME, Pelletreau KN, Moustafa A, Bhattacharya D (2011) The making of a photosynthetic animal. J Exp Biol 214: 303–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Gannes LZ, OBrien DM, del Rio CM (1997) Stable isotopes in animal ecology: Assumptions, caveats, and a call for more laboratory experiments. Ecology 78: 1271–1276. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Klumpp DW, Griffith CL (1994) Contributions of phototrophic and heterotrophic nutrition to the metabolic and growth requirements of 4 species of giant clam (Tridacnidae). Mar Ecol Prog Ser 115: 103–115. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Muscatine L (1967) Glycerol excretion by symbiotic algae from corals and Tridacna and its control by the host. Science 156: 516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Maruyama T, Heslinga GA (1997) Fecal discharge of zooxanthellae in the giant clam Tridacna derasa, with reference to their in situ growth rate. Mar Biol 127: 473–477. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Hirose E, Iwai K, Maruyama T (2006) Establishment of the photosymbiosis in the early ontogeny of three giant clams. Mar Biol 148: 551–558. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Palumbi S, Martin A, Romano S, McMillan W, Stice L, et al. (1991) The simple fool's guide to PCR, version 2.0. University of Hawaii, Honolulu: Privately published, compiled by S Palumbi. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Hanyuda T, Arai S, Ueda K (2000) Variability in the rbcL introns of Caulerpalean algae (Chlorophyta, Ulvophyceae). J Plant Res 113: 403–413. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Overviews of Plankobranchus ocellatus . (A) Dorsal views of a freshly collected intact P. ocellatus individual. (B) An anesthetized individual with spread parapodia. The tissue region in the red square was dissected and used for DNA extraction.

(TIF)

Percentage abundance of rbcL sequences from source algae in P. ocellatus *.

(XLS)

(XLS)

(XLS)