Abstract

A simple design of “turn-on” fluorescent sensor for mercury was demonstrated based on structure-switching DNA with a low detection limit of 3.2 nM and high selectivity.

Mercury is a highly toxic and widespread pollutant in the environment. Mercury can be a source of environmental contamination when present in by-products of burning coal, mine tailings and wastes from chlorine–alkali industries.1–3 These contaminations can cause a number of severe health problems such as brain damage, kidney failure, and various cognitive and motion disorders.4 Therefore, a sensitive and selective mercury detection in the environment and food industry is highly demanded. Towards this goal, many mercury sensors based on small fluorescent organic molecules,5–12 proteins,13–15 oligonucleotides,16,17 genetically engineered cells,18 conjugated polymers,19 foldamers,20,21 membranes,22,23 electrodes,24,25 and nanomaterials26–31 have been reported. Despite the progress, few sensors show enough sensitivity and selectivity for detection of mercury in aqueous solution. Those sensors that could meet the requirement remain complicated to design and operate, or are “turn-off” sensors that are vulnerable to interferences, making it difficult for facile on-site and real-time detection and quantification. In particular, an interesting example is environmental-monitoring applications, such as mercury detection in drinking water, in which a detection limit below 10 nM (the maximum contamination level defined by US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)) is required. However, only a few reported sensors can reach this sensitivity.12,13,18,27,28 Therefore, a simple sensor with high sensitivity and selectivity for facile on-site and real-time mercury detection is still needed.

Oligonucleotides provide an attractive methodology for mercury sensing. Ono and co-workers reported that Hg2+ has a unique property to bind specifically to two DNA thymine bases (T) and stabilize T–T mismatches in a DNA duplex, and demonstrated a fluorescent sensor for Hg2+ ion detection.14,32 In their sensor design, one single-stranded thymine-rich DNA strand was labeled with a fluorophore and a quencher at each end. In the presence of Hg2+ ions, the two ends of DNA would become close to each other through thymine–Hg–thymine base pair formation, resulting in fluorescence decrease due to an enhanced quenching effect between the fluorophore and the quencher. A detection limit of 40 nM was reported. As other quenchers or external environmental species might also cause decrease of fluorescence and give a “false positive” results, a “turn-on” sensor is preferred. This Hg2+ ions induced stabilization effect on T–T mismatches have also been applied to design colorimetric sensors by using DNA and gold nanoparticles in chemically labeled26,30 or label-free methods.28,29,31 Recently, our group reported a highly sensitive “turn-on” mercury sensor by introducing thymine–thymine mismatches in the stem region of the uranium-specific DNAzyme.33 Hg2+ enhanced the DNAzyme activity through allosteric interactions, and a detection limit as low as 2.4 nM was achieved using the catalytic beacon method.34–36 Being highly sensitive and selective, however, this sensor required the use of 1 μM UO22+ for DNAzyme activity. This drawback gave us the motivation to find an alternative method for mercury sensing, with a comparable sensitivity but without the need to use other toxic metal ions as co-factors. Herein, we report a simple design of highly sensitive and selective “turn-on” fluorescent mercury sensor based on structure-switching DNA. The sensing process can be completed in less than 5 min, with a detection limit of 3.2 nM (0.6 ppb). Furthermore, mercury detection in pond water was performed to demonstrate the practical use of this sensor.

Fluorescent sensors based on structural switching aptamer have been developed to detect a number of non-metal ions such as adenosine-5′-triphosphate (ATP),37–39 cocaine,40 thrombin,41 and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF).42 Here we report a simple design that is not based on aptamers, but based on structure-switching of DNA containing thymine–thymine mismatches to detect metal ions. The design of the structure switching mercury sensor is shown in Fig. 1. The sensor system contains a 33-mer DNA (Strand A) with a FAM labeled at the 5′ end and a 10-mer DNA (strand B) with a Black Hole Quencher-1 labeled at the 3′ end (Fig. 1(a)). Strand A can be divided into three segments. The first segment (in red) together with the second segment (in purple) hybridize with strand B. Five self-complementary base pairs (bps) separated by seven thymine–thymine mismatches are introduced to the second and third segment (in green). In the absence of Hg2+, as DNA strands A and B are hybridized, the fluorophore and the quencher are close to each other, resulting in fluorescence quenching due to fluorescence resonance energy transfer. However, in the presence of Hg2+, the formation of thymine–Hg–thymine base pairs will induce the folding of the last two segments (in purple and green) into a hairpin structure (Fig. 1(a)). As a result, only five base pairs remain between strand A and B, which is not long enough to keep both strands stable at 100 mM salt concentration at room temperature. Therefore, strand B will be released from strand A, “turning-on” the signal from the quenched fluorophore. The fluorescence spectra of the sensor before and after the addition of 1 μM Hg2+ is shown in Fig. 1(b). About 8× fluorescence increase at 518 nm peak was observed. The quantum yield of the FAM conjugated to the DNA sensor is estimated to be ~66% (see ESI†) and little quenching of FAM fluorescence was observed upon addition of 1 μM Hg2+.

Fig. 1.

(a) Schematic of the “turn-on” fluorescent mercury sensor design. The 33-mer DNA strand (strand A) with a FAM attached at the 5′ end was hybridized with a 10-mer DNA (strand B) with a Black Hole Quencher-1 attached at the 3′ end, resulting in fluorescence quenching. In the presence of Hg2+, the folding of strand A releases strand B and increases the fluorescence. (b) Fluorescence spectra of the sensor in the absence of and after the addition of 1 μM Hg2+ ions for 10 min.

To study the Hg2+ induced structure-switching of the sensor system, the sensor solutions were treated with Hg2+ ions of various concentrations, and the kinetics of the fluorescence increase at 518 nm was monitored. As shown in Fig. 2(a), higher concentrations of Hg2+ ions resulted in more fluorescence emission enhancement. To quantify the Hg2+ ions, the fluorescence increase in the first 3 min after addition of different concentrations of Hg2+ ions was collected and compared. The calibration curve (Fig. 2(b)) had a sigmoid shape and was fit to a Hill plot with a Hill coefficient of 2.4. This results indicate that the Hg2+ binding to the DNA strand A is a positively cooperative process, and the binding of one Hg2+ facilitates the binding of another Hg2+ onto the same strand. Although there are seven binding sites in strand A, the release of strand B happens after binding to approximately 2.4 Hg2+ ions. Through fitting the calibration curve in Fig. 2(b) to a Hill plot, a dissociation constant of 471 nM was obtained (see ESI†). This sensor has a detection limit of 3.2 nM based on 3α/slope, which is lower than US EPA defined toxicity level of Hg2+ in drinking water (10 nM). The calibration saturated at 800 nM, meaning that the detection range of this sensor is from 3 nM to 800 nM.

Fig. 2.

(a) Kinetics of the fluorescence increase in the presence of varying concentrations of Hg2+ ions. (b) Calibration curve of “turn-on” fluorescent mercury sensor (fitted to Hill plot with a Hill coefficient of 2.4). The fluorescence increase was calculated from the first 3 min after addition of Hg2+ ions. Inset: Sensor responses at low Hg2+ ion concentrations.

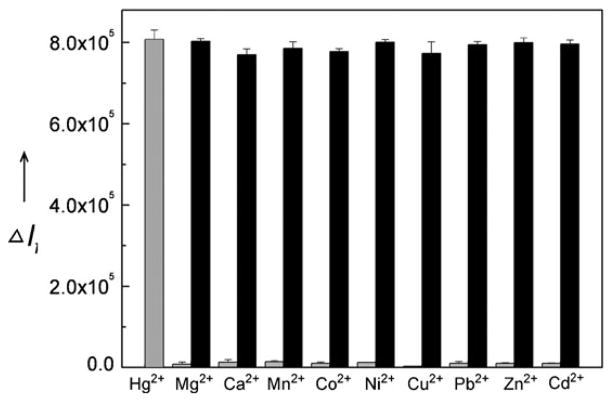

To determine the selectivity of the sensor, 1 μM of each of metal ion was individually added to the sensor solution and the fluorescence increase was monitored. As shown in Fig. 3 (grey bars), among the metal ions tested (Mg2+, Ca2+, Mn2+, Co2+, Ni2+, Cu2+, Pb2+, Zn2+, Cd2+, and Hg2+), only Hg2+ resulted in significant fluorescence signal increase. In addition, 1 μM of Hg2+ and 1 μM of another metal ion were added together to the sensor solution. The fluorescence response of the Hg2+–M2+ pair (Fig. 3, black bar) suggests excellent selectivity of Hg2+ over other metal ions as well.

Fig. 3.

Selectivity of the Hg2+ sensor. Gray bars represent fluorescence responses 8 min after addition of 1 μM of other metal ion (from left to right: Hg2+, Mg2+, Ca2+, Mn2+, Co2+, Ni2+, Cu2+, Pb2+, Zn2+, and Cd2+). Black bars represent fluorescence responses after addition of 1 μM of Hg2+ together with 1 μM of one other metal ion.

With excellent sensitivity and selectivity in buffer solution, our sensor was further tested with pond water collected on the University of Illinois campus. Using standard addition method, Hg2+ ions were added into the sensor solution in the pond water to the final concentration of 200 nM and 207% fluorescence enhancement was observed (Fig. 4). This result is similar to the fluorescence enhancement (231%) observed for the sensor in pure water in the presence of 200 nM Hg2+, indicating that our sensor is able to detect mercury in pond water with little interference.

Fig. 4.

Fluorescence spectra corresponding to the analysis of Hg2+ in pond water: pond water containing no Hg2+ (black triangle) or 500 nM Hg2+ (red circle) was added into the sensor solution, the dilution factor was 2.8. Inset of the figure shows the kinetics of the fluorescence increase after addition of the pond water.

In summary, we designed a highly sensitive and selective fluorescent sensor for mercury based on structure-switching DNA. Hg2+ induced the folding of fluorophore labeled DNA strand by thymine–Hg–thymine formation, which released the hybridized DNA strand with the quencher and increased the fluorescence. This sensor has the detection limit of 3.2 nM, which is lower than the EPA limit of Hg2+ ions in drinking water (10 nM). This simple design of highly sensitive and selective sensor makes it possible for on-site and real-time mercury detection in environmental and other applications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work has been supported by the US Department of Energy (DE-FG02-08ER64568), the NSF (DMR-0117792, CTS-0120978 and DMI-0328162), and the US National Institute of Health (ES016865).

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available: Experimental section, Fig. S1, Dissociation constant calculations. See DOI: 10.1039/b812755g

Notes and references

- 1.Joensuu OI. Science. 1971;172:1027. doi: 10.1126/science.172.3987.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clarkson TW. Environ Health Perspect. 1993;100:31. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9310031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malm O. Environ Res. 1998;77:73. doi: 10.1006/enrs.1998.3828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tchounwou PB, Ayensu WK, Ninashvili N, Sutton D. Environ Toxicol. 2003;18:149. doi: 10.1002/tox.10116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prodi L, Bargossi C, Montalti M, Zaccheroni N, Su N, Bradshaw JS, Izatt RM, Savage PB. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:6769. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guo X, Qian X, Jia L. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:2272. doi: 10.1021/ja037604y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caballero A, Martinez R, Lloveras V, Ratera I, Vidal-Gancedo J, Wurst K, Tarraga A, Molina P, Veciana J. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:15666. doi: 10.1021/ja0545766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang YK, Yook KJ, Tae J. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:16760. doi: 10.1021/ja054855t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim SH, Kim JS, Park SM, Chang SK. Org Lett. 2006;8:371. doi: 10.1021/ol052282j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ha-Thi MH, Penhoat M, Michelet V, Leray I. Org Lett. 2007;9:1133. doi: 10.1021/ol070118l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nolan EM, Lippard SJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:5910. doi: 10.1021/ja068879r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoon S, Miller EW, He Q, Do PH, Chang CJ. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2007;46:6658. doi: 10.1002/anie.200701785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen P, He C. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:728. doi: 10.1021/ja0383975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matsushita M, Meijler MM, Wirsching P, Lerner RA, Janda KD. Org Lett. 2005;7:4943. doi: 10.1021/ol051919w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wegner SV, Okesli A, Chen P, He C. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:3474. doi: 10.1021/ja068342d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ono A, Togashi H. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2004;43:4300. doi: 10.1002/anie.200454172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chiang CK, Huang CC, Liu CW, Chang HT. Anal Chem. 2008;80:3716. doi: 10.1021/ac800142k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Virta M, Lampinen J, Karp M. Anal Chem. 1995;67:667. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu X, Tang Y, Wang L, Zhang J, Song S, Fan C, Wang S. Adv Mater. 2007;19:1471. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao Y, Zhong Z. Org Lett. 2006;8:4715. doi: 10.1021/ol061735x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao Y, Zhong Z. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:9988. doi: 10.1021/ja062001i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamini Y, Alizadeh N, Shamsipur M. Anal Chim Acta. 1997;355:69. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chan WH, Yang RH, Wang KM. Anal Chim Acta. 2001;444:261. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Widmann A, van den Berg CMG. Electroanalysis. 2005;17:825. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ostatna V, Palecek E. Langmuir. 2006;22:6481. doi: 10.1021/la061424v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee JS, Han MS, Mirkin CA. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2007;46:4093. doi: 10.1002/anie.200700269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Darbha GK, Ray A, Ray PC. ACS Nano. 2007;1:208. doi: 10.1021/nn7001954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li D, Wieckowska A, Willner I. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2008;47:3927. doi: 10.1002/anie.200705991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu CW, Hsieh YT, Huang CC, Lin ZH, Chang HT. Chem Commun. 2008:2242. doi: 10.1039/b719856f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xue X, Wang F, Liu X. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:3244. doi: 10.1021/ja076716c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang L, Zhang J, Wang X, Huang Q, Pan D, Song S, Fan C. Gold Bull. 2008;41:37. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miyake Y, Togashi H, Tashiro M, Yamaguchi H, Oda S, Kudo M, Tanaka Y, Kondo Y, Sawa R, Fujimoto T, Machinami T, Ono A. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:2172. doi: 10.1021/ja056354d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu J, Lu Y. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2007;46:7587. doi: 10.1002/anie.200702006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li J, Lu Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:10466. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu J, Lu Y. Anal Chem. 2003;75:6666. doi: 10.1021/ac034924r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu J, Lu Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:9838. doi: 10.1021/ja0717358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jhaveri SD, Kirby R, Conrad R, Maglott EJ, Bowser M, Kennedy RT, Glick G, Ellington AD. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:2469. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nutiu R, Li Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:4771. doi: 10.1021/ja028962o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nutiu R, Li Y. Chem–Eur J. 2004;10:1868. doi: 10.1002/chem.200305470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stojanovic MN, de Prada P, Landry DW. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:4928. doi: 10.1021/ja0038171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hamaguchi N, Ellington A, Stanton M. Anal Biochem. 2001;294:126. doi: 10.1006/abio.2001.5169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang C, Jockusch S, Vicens M, Turro NJ, Tan W. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:17278. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508821102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.