Abstract

Objectives

We seek to identify predictors of 30-day mortality after balloon aortic valvuloplasty (BAV).

Background

To date, there is no validated method of predicting patient outcomes after percutaneous aortic valve interventions.

Methods

Data for consecutive patients with severe aortic stenosis who underwent BAV at the Mount Sinai Medical Center from January 2001 to July 2007 were retrospectively reviewed. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to identify significant predictors of 30-day mortality and the resultant model was compared to the EuroSCORE using Akaike's Information Criterion and area under the receiver-operating curve (AUC).

Results

The analysis included 281 patients (age 83 ± 9 yrs, 61% women, aortic valve area: 0.64 ± 0.2 cm2), 36 (12.8%) of whom died within 30 days of BAV. Identified risk factors for 30-day mortality, critical status, renal dysfunction, right atrial pressure, and cardiac output, we used to construct the CRRAC the AV risk score. Thirty-day survival was 72% in the highest tertile versus 94% in the lower two tertiles of the score. Compared to the additive and logistic EuroSCORE, the risk score demonstrated superior discrimination (AUC = 0.75 vs. 0.60 and 0.63, respectively).

Conclusions

We derived a risk score, the CRRAC the AV score, that identifies patients at high-risk of 30-day mortality after BAV. Validation of the developed risk prediction score, the CRRAC the AV score, is needed in other cohorts of post-BAV patients and potentially in patients undergoing other catheter-based valve interventions.

Keywords: aortic valve stenosis, EuroSCORE, percutaneous

INTRODUCTION

Percutaneous balloon aortic valvuloplasty (BAV) was first performed in patients with acquired severe aortic stenosis (AS) by Cribier in 1986, at which time it was anticipated to be an alternative to surgical aortic valve replacement (AVR).(1) In the current era, BAV is recommended for the treatment of severe AS in children and young adults,(2) but initial enthusiasm surrounding this technique as an alternative to surgical AVR in older patients with fibrocalcific AS has waned. Despite significant acute improvement in aortic valve area, mean aortic valve gradients, cardiac output, symptoms, and functional class, the procedure has historically been associated with significant peri-procedural and short-term morbidity and mortality, limiting its widespread use.(3–5) Furthermore, long-term survival rates after BAV are comparable to those seen with untreated severe AS.(5–7)

Recent data on BAV suggest that technical and procedural advances have decreased procedural complication rates in high-risk patients, suggesting that increased utilization of the procedure is warranted in the growing subset of patients with limited therapeutic options.(8–11) As such, BAV is currently used as a palliative procedure for high-risk patients who are precluded from surgical AVR or as a bridge to surgery in hemodynamically unstable patients.(2) Additionally, BAV is increasingly being used as a bridge to transcatheter aortic valve implantation given the procedure's limited availability in the United States.(11,12)

The EuroSCORE is a widely used scoring system for the prediction of short-term mortality after cardiac surgery.(13,14) Despite concerns regarding the accuracy of the EuroSCORE in estimating mortality after AVR, it is nonetheless used to evaluate appropriateness of surgical AVR in those with severe symptomatic AS.(15–17) Few options exist for those deemed not to be acceptable surgical candidates. These patients are offered either continued medical management with the expectation of continued clinical deterioration, BAV as a palliative option, or transcatheter aortic valve implantation in a select few.(2,18)

Further risk stratification in patients with severe symptomatic AS may aid in better procedure selection, in periprocedural optimization, and ultimately in improving clinical outcomes. However, predicting mortality in these very high-risk patients using a scoring system generated in a large population-based study is limited given that these patients are underrepresented in such studies.(16) Additionally, although predictive of general mortality, the EuroSCORE score is specifically designed for estimating post-operative mortality.(13,19) Many of the patient characteristics included in these scores, such as surgery other than isolated coronary artery bypass, surgery on the thoracic aorta, and post infarct septal rupture, have little relevance to catheter-based interventions. We therefore sought to identify predictors of 30-day mortality post-BAV and to develop a risk prediction score for high-risk patients with severe symptomatic AS.

METHODS

Study sample

Subjects were consecutively enrolled adult patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis referred for BAV from January 2001 until July 2007 at The Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York City. A total of 376 BAV procedures were performed during the study period. Patients undergoing repeat procedures were excluded from this analysis, leaving 292 patients for further analysis. The Mount Sinai School of Medicine Institutional Review Board approved retrospective review of patient data for this study.

Balloon Aortic Valvuloplasty Procedural Details

BAV was performed according to standard techniques using the retrograde approach. The mean aortic transvalvular pressure gradient was measured using simultaneous, dual catheter measurements in the aortic root and left ventricle. Cardiac output was measured using the standard thermodilution method and aortic valve area was calculated using the Gorlin formula.(20) Incremental balloons, sized 20 to 25 mm, were used with a goal reduction in peak trans-aortic valve pressure gradients to 33 to 50% of baseline. Balloons were maximally in?ated without rapid pacing to exert a maximum dilatational force that resulted in balloon rupture in approximately 15% of patients. Aortograms were performed before and after BAV to assess the severity of baseline and post-BAV aortic regurgitation. All hemodynamic data were measured and recorded before and after BAV.

Study protocol

All relevant data were extracted from a centralized database within the Cardiac Catheterization Laboratory at the Mount Sinai Medical Center. Pre-procedural clinical data included in the database were collected using standardized interview forms prior to initiation of the procedure. These included demographic data, comorbid illnesses, laboratory parameters, and concurrent medications. Verification of comorbid illnesses was left to the discretion of the interviewing physician. Procedure-related data were entered into the database at the time of the procedure, and included relevant hemodynamic measurements as well as technical characteristics of the procedure.

Statistical analysis

Unadjusted associations between subject characteristics and 30-day mortality were assessed with Cox proportional hazards regression. Potential predictors of 30-day mortality included age, sex, comorbid illnesses, illness severity, additive and logistic EuroSCORE, (13,19) and pre-procedural right heart catheterization hemodynamic measurements. Survival time was measured beginning at the date of the index procedure until death. Individuals were censored at the time of last follow-up, repeat BAV, or surgical AVR. Individuals with missing data for >10% of the potential predictors were excluded from the analysis (11 patients).

Cox proportional hazards regression was used to identify significant predictors of 30-day mortality. A stepwise selection algorithm with conservative entry and retention significance thresholds (p < 0.01) was used to facilitate variable selection. Variables included in the selection algorithm were based on individual components of the EuroSCORE(13,14) and preprocedural hemodynamic data. Specifically, our initial models included: age; gender; presence of diabetes mellitus, peripheral arterial disease, kidney dysfunction (creatinine > 2.26 mg/dl), hyperlipidemia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, malignanacy, bacterial endocarditis, pulmonary hypertension, and critical status (ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation, aborted sudden death, preoperative ventilation, preoperative inotropic support, intraaortic balloon counterpulsation or preoperative anuria or oliguria); history of stroke, prior cardiovascular surgery, unstable angina, and recent myocardial infarction; categorized left ventricular dysfunction; symptoms of heart failure, angina, or syncope, shock; and pre-BAV right atrial pressure, cardiac output, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, mean transvalvular gradient, and aortic valve area. Excluded variables felt to hold significant clinical relevance were sequentially added back to the model on the basis of minimizing Akaike's Information Criterion (AIC).(21)

Once a final model was constructed, a scoring algorithm was created based on the model. Kaplan-Meier plots were created to assess survival by score tertiles. The score was then compared separately to the additive and the logistic EuroSCORE, using the AIC. Model discrimination was assessed by calculating the time-dependent area under the curve (AUC) and by visual inspection of receiver-operator characteristic curves with the survivalROC package in R.(22) Model calibration, which assesses agreement between observed and predicted patient outcomes, was assessed using the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test.(23) All statistical analyses were performed using SAS v9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and R v2.9.1.(24)

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Two hundred eighty-one patients were included in this analysis. The study cohort was mostly female (60.8%) and generally elderly (mean age: 83.0 ± 9.4 years) with a high prevalence of heart failure symptoms (87.3%) and of left ventricular dysfunction (44.8%; Table 1). Pulmonary hypertension was also present in the majority of patients (54.1%). Subject characteristics that were significantly associated with an increased hazard of death at 30 days in univariate analyses included EuroSCORE (both additive and logistic models), renal dysfunction, critical status, and baseline pulmonary hypertension (Table 1). Baseline pre-BAV hemodynamics confirmed a high prevalence of critical AS. Elevations of right atrial pressure and pulmonary capillary wedge pressure were common. Pre-procedural hemodynamic parameters associated with increased hazard of death at 30 days included right atrial pressure and pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics in the overall study cohort and unadjusted hazard ratio of death at 30-days post-BAV.

| Overall (n = 281) | Unadjusted HR (95% CI) 30-day mortality | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 111 (39.2%) | 1.21 (0.63 – 2.33) | 0.57 |

| Age (years) | 83.0 ± 9.4 | 0.98 (0.95 – 1.02) | 0.32 |

| Additive EuroSCORE | 11.8 ± 3.8 | 1.09 (1.01 – 1.18) | 0.02 |

| Logistic EuroSCORE | 32.8 ± 22.6 | 1.02 (1.00 – 1.03) | 0.01 |

| BSA (m2) | 1.71 ± 0.24 | 0.87 (0.22 – 3.51) | 0.85 |

| Past medical history | |||

| Diabetes | 78 (27.6%) | 1.17 (0.58 – 2.38) | 0.67 |

| COPD | 48 (17.0%) | 0.58 (0.21 – 1.65) | 0.31 |

| PAD | 57 (20.1%) | 1.85 (0.91 – 3.76) | 0.09 |

| Stroke | 33 (11.7%) | 0.95 (0.34 – 2.68) | 0.92 |

| Prior CV surgery | 59 (20.9%) | 1.45 (0.70 – 3.00) | 0.32 |

| Renal dysfunction | 53 (18.7%) | 3.23 (1.65 – 6.32) | <0.001 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 155 (54.8%) | 0.67 (0.35 – 1.29) | 0.23 |

| Smoker | 33 (11.7%) | 0.41 (0.10 – 1.72) | 0.22 |

| LV function | 0.10 | ||

| Normal | 108 (38.2%) | Reference group | |

| Moderately reduced | 42 (14.8%) | 2.44 (0.89 – 6.74) | |

| Severely reduced | 85 (30.0%) | 2.42 (1.02 – 5.77) | |

| Symptoms pre-procedure | |||

| Heart failure | 247 (87.3%) | 0.64 (0.28 – 1.46) | 0.29 |

| Angina | 70 (24.7%) | 0.69 (0.29 – 1.66) | 0.41 |

| Syncope | 17 (6.0%) | 0.56 (0.08 – 4.10) | 0.57 |

| Stability pre-procedure | |||

| Shock | 17 (6.0%) | 2.41 (0.94 – 6.20) | 0.07 |

| Critical status | 39 (13.8%) | 3.69 (1.87 – 7.29) | <0.0005 |

| Unstable angina | 37 (13.1%) | 0.63 (0.19 – 2.05) | 0.44 |

| Recent MI | 35 (12.4%) | 0.63 (0.19 – 2.05) | 0.44 |

| Pulmonary HTN | 153 (54.1%) | 2.45 (1.18 – 5.08) | <0.05 |

| Hemodynamic data | |||

| RA pressure (mmHg) | 8.0 (5.0 – 11.0) | 1.10 (1.05 – 1.15) | <0.0001 |

| PCWP (mmHg) | 18.0 (12.0 – 24.0) | 1.05 (1.01 – 1.08) | <0.05 |

| CO (1/min) | 4.1 (3.4 – 5.0) | 0.82 (0.63 – 1.07) | 0.15 |

| Mean transvalvular gradient (mmHg) | 42.0 (32.0 – 56.0) | 1.00 (0.99 – 1.02) | 0.73 |

| AVA (cm2) | 0.60 (0.50 – 0.80) | 0.21 (0.03 – 1.49) | 0.12 |

Values displayed are mean values ± standard deviation or median values (interquartile range) based of the normalcy of distribution or n (%) for categorical variables.

AVA = aortic valve area; BSA = body surface area; CO = cardiac output; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CV = cardiovascular; HTN = hypertension; LV = left ventricle; MI = myocardial infarction PCWP = pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; RA = right atrial

Balloon Aortic Valvuloplasty Outcomes

Of 281 subjects included in the analysis, 36 (12.7%) died within 30 days of BAV. The median follow-up time was 115 days (inter-quartile range 10 to 346 days). Four patients died on the day of the procedure. Hemodynamic parameters significantly improved after BAV. Aortic valve area increased from 0.64±1.8 cm2 to 1.23±0.3 cm2 (mean ± standard deviation; p<0.0001) with a concomitant decrease in mean transvalvular pressure gradients (44.8±18.0 to 16.6±9.0 mmHg; p<0.0001). Additionally, significant reductions in right atrial pressure (8.6±8.6 to 7.4±3.8 mmHg; p<0.0001) and pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (18.8±7.9 to 15.4±6.0 mmHg; p<0.0001) and an increase in cardiac output (4.3±1.3 to 4.9±1.7 L/min; p<0.0001) were observed post-BAV.

Prediction of 30-day Mortality

Using a step-wise selection procedure, critical status, renal dysfunction, and pre-BAV right atrial pressure were selected as significant predictors of 30-day mortality. Pre-BAV cardiac output was included in the model on the basis of minimizing the AIC (Table 2). This model provided a better fit of our data than models comprised of either the additive or logistic EuroSCORE as judged by the AIC. The proportional hazards assumption was satisfied for all covariates in the final models.

Table 2.

Predictors of 30-day mortality post-BAV based on multivariable CRRAC the AV model (critical status, renal dysfunction, pre-procedure RAP, and cardiac output) compared to additive and logistic EuroSCORE alone.

| Model | Hazard ratio | 95% Confidence interval | P value | AIC* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRRAC the AV | 363 | |||

| Critical status | 3.54 | 1.78 – 7.03 | <0.005 | |

| Renal dysfunction | 3.20 | 1.54 – 6.68 | <0.0005 | |

| Pre-procedural RA pressure (per 1 mmHg increase) | 1.07 | 1.02 – 1.13 | <0.01 | |

| Cardiac output (per 1 L/min increase) | 0.77 | 0.58 – 1.02 | 0.07 | |

| Additive EuroSCORE only (per 1 point increase in score) | 1.09 | 1.01 – 1.18 | <0.05 | 385 |

| Logistic EuroSCORE only (per 1 point increase in score) | 1.02 | 1.00 – 1.03 | <0.05 | 384 |

Lower values indicate a better fit of the regression model to the observed data.

Results displayed per 1 unit increase.

AIC = Akaike's Information Criterion; RA = right atrial

We calculated a summary risk score for 30-day mortality by dividing each coefficient by the smallest coefficient. Additionally, in order to ease clinical application, we dichotomized pre-BAV cardiac output around the mean (4.1 L/min) such that those with a cardiac output ≤ 4.1 L/min were defined as having low cardiac output. The score was defined as:

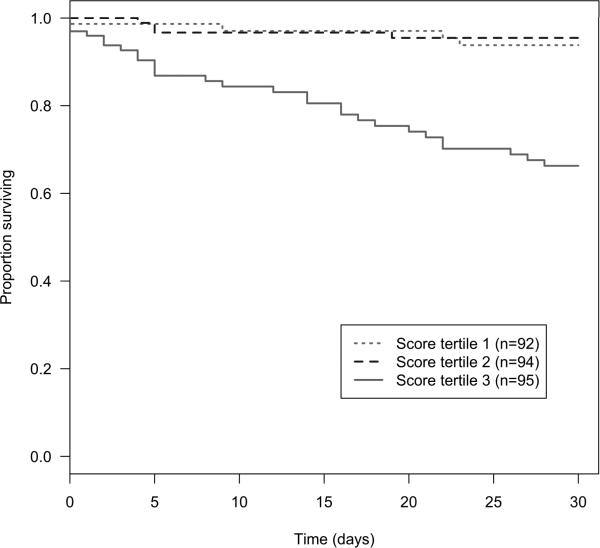

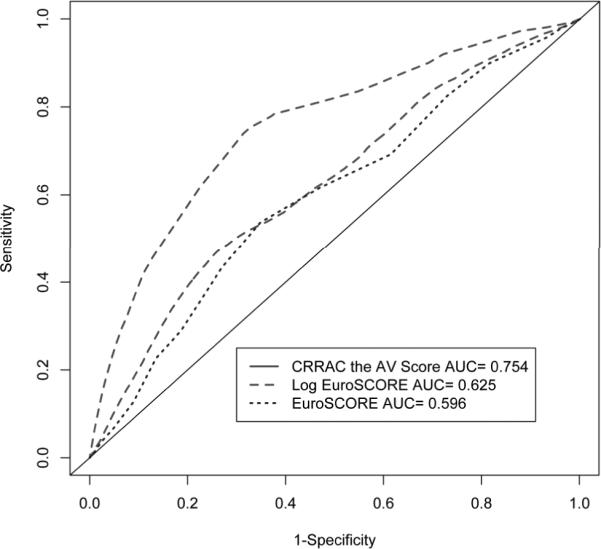

The CRRAC (Critical status, Renal dysfunction, Right Atrial pressure, Cardiac output) the AV risk score values ranged from 2 to 52, with a median score of 15. This score was significantly associated with time to death within 30 days post-BAV (HR per point increase 1.08, 95% CI 1.05 – 1.10; p<0.0001). The score demonstrated better discrimination than models comprised of either the additive or logistic EuroSCORE (Figure 1). Additionally, the Hosmer-Lemeshow test of calibration demonstrated good agreement between observed and predicted risk (p=0.92). When categorized into tertiles, the increase in risk appeared concentrated among subjects in the highest tertile (score ≥20) of risk score such that compared to the lowest tertile (score ≤10), the hazard ratio for 30-day mortality was 1.10 (95% CI 0.34 – 3.61; p=0.87) in the middle tertile and 5.82 (95% CI 2.38 – 14.19; p<0.0001) for the highest (Table 3). Similarly, the 30-day survival of subjects in the highest tertile of risk score was 72.2%, in contrast to 94.4% and 92.2% for subjects in the lowest and middle tertiles, respectively (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Time-dependent areas under the receiver-operating characteristic curves for models predicting 30-day mortality.

Table 3.

Risk of death at 30-day mortality post-BAV stratified by the CRRAC the AV risk score calculated as: 17*critical + 15*renal dysfunction + RA pressure pre-BAV + 7*low cardiac output.

| Tertile (Score) | Number of subjects | Number of deaths | HR (95% CI) for death at 30 days post-BAV | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lowest (≤10) | 92 | 6 | Referent | Referent |

| Middle (11 – 19) | 94 | 5 | 1.10 (0.34 – 3.61) | 0.87 |

| Highest (≥20) | 95 | 25 | 5.82 (2.38 – 14.19) | <0.0001 |

BAV = balloon aortic valvuloplasty; RA = right atrial

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves for survival to 30 days post-BAV by tertiles of the CRRAC the AV risk score based on critical status, renal dysfunction, pre-BAV RA pressure, and cardiac output.

DISCUSSION

In our cohort of 281 patients with symptomatic AS referred for BAV, we identified renal dysfunction, critical clinical status, increased pre-BAV right atrial pressure, and low cardiac output as predictors of 30-day mortality following BAV and developed a risk prediction score based on these high risk features. While we also demonstrate that the additive and logistic EuroSCORE were associated with 30-day mortality, the discrimination of such measures, as defined by area under the receiver operating characteristic curves, in predicting 30-day mortality was poor in comparison to our scoring algorithm. Individuals in the highest tertile of risk score values possessed a 30-day survival of only 73.7%, compared to 94.4% and 92.2% for subjects in the lower tertiles. Consequently, our data suggest that subjects with a CRRAC the AV Score greater than or equal to 20 constitute a very high-risk subset (Table 4).

Table 4.

Summary of the CRRAC the AV Score.

| CRRAC the AV Score | Points Allocated |

|---|---|

| Critical status (ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation, aborted sudden death, preoperative ventilation, preoperative inotropic support, intraaortic balloon counterpulsation or preoperative anuria or oliguria) | 17 |

| Renal dysfunction (creatinine > 2.26 mg/dl) | 15 |

| Pre-procedural RA pressure (mmHg) | 1 * RA pressure |

| Low cardiac output (≤ 4.1 L/min) | 7 |

| SUM | High risk if ≥20 |

Risk assessment for patients undergoing a myriad of cardiovascular surgeries, including AVR, is often performed using the additive or logistic EuroSCORE.(13–17,19,25,26) The score is widely used and has even been expanded to percutaneous procedures given its inclusion of a number of risk factors universally associated with poor patient outcomes.(27,28) As such, the EuroSCORE serves as the basis of our presented analyses. However, the EuroSCORE includes operation-related factors that hold little relevance to those undergoing percutaneous BAV, such as surgery other than isolated coronary artery bypass graft surgery, surgery on the thoracic aorta, or presence of a post-infarct septal rupture.(13,19) These variables likely diminishing the score's predictive power in non-surgical patients. Additionally, given that the EuroSCORE was created based on data from a population-based study of those presenting for cardiac surgery, its applicability to the highest risk patient group is unclear.(16)

In order to maximize clinical utility of any derived prediction algorithm, we sought to identify predictors of 30-day mortality post-BAV that were easily attainable in this sickest of cohorts. Thus, we did not include left heart catheterization measurements as potential predictors as their selection would imply that a left heart catheterization is necessary for proper risk stratification of individuals prior to BAV. Our findings indicate that a parsimonious model comprised of only four risk factors is superior to the EuroSCORE for predicting 30-day mortality and demonstrates desirable discrimination characteristics. These factors, when considered together, identify a uniquely high-risk subset of individuals undergoing BAV. Whether optimization of the clinical status of patients within this high-risk subset prior to BAV will result in improved outcomes, or whether these predictors merely identify a subset of individuals that are too ill to respond to interventions such as BAV, merits further evaluation.

The predictors identified in our analyses each possess implications for patient management. Critical status, renal dysfunction, increased baseline RA pressure, and low cardiac output are each indicative of a decompensated state, an obvious marker of short-term mortality and often a consequence of severe AS. The association between 30-day mortality and renal dysfunction is of particular interest as kidney disease has consistently been linked to cardiovascular disease and poor cardiovascular outcomes,(29,30) as well as increased aortic valve calcification.(31,32) As such, patients with chronic kidney disease may possess more heavily calcified valves that are less amenable to BAV. We did not find a significant difference in post-BAV aortic valve areas in chronic kidney disease compared to non-chronic kidney disease patients to support this hypothesis (not shown), but increased recoil in this patient subset is plausible.

Our study possesses several limitations. First, the presented analyses are based on a relatively small cohort from a single center. Although within the BAV literature our study includes a relatively large number of patients, confirmation and validation of our risk prediction model in other cohorts is necessary in order for changes in clinical practice to be suggested. Second, given consistent practices at the study site, we did not evaluate whether different procedural techniques, such as the anterograde approach, would affect outcomes in higher-risk patients. Third, we did not adjust for a quantitative index of renal function, and consequently cannot determine whether the increased risk associated with kidney disease is linearly associated with reduced glomerular filtration rate. Fourth, we do not possess sufficient clinical data on our cohort to calculate and compare the STS prediction score to the CRRAC the AV score. Fifth, some operators may find the CRRAC the AV score cumbersome to use in daily practice. Once validated, an electronic and/or web-based risk calculator may be needed to be developed. Lastly, causes of death were not available in our database, thereby limiting our analysis to all-cause mortality.

In conclusion, we have identified the presence of preprocedural critical status, renal dysfunction, elevated baseline RA pressure, and low cardiac output as significant predictors of 30-day mortality post-BAV. Additional study is warranted to determine whether modifying these high-risk characteristics prior to BAV improves patient outcomes or whether patients with these characteristics represent a cohort too ill for BAV. Validation of the developed risk prediction score, the CRRAC the AV score, is needed in other cohorts of post-BAV patients and potentially in patients undergoing other catheter-based valve interventions.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: Dr. Elmariah is supported by a grant from the National Heart Lung, and Blood Institute (T32 HL007824). Dr. Lubitz is supported by a grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Intsitute (T32 HL007575).

Footnotes

Disclosures: None

REFERENCES

- 1.Cribier A, Savin T, Saoudi N, Rocha P, Berland J, Letac B. Percutaneous transluminal valvuloplasty of acquired aortic stenosis in elderly patients: an alternative to valve replacement? Lancet. 1986;1(8472):63–7. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)90716-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Chatterjee K, de Leon AC, Jr., Faxon DP, Freed MD, Gaasch WH, Lytle BW, Nishimura RA, O'Gara PT. ACC/AHA 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (writing committee to revise the 1998 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease): developed in collaboration with the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists: endorsed by the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation. 2006;114(5):e84–231. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.176857. and others. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McKay RG. The Mansfield Scientific Aortic Valvuloplasty Registry: overview of acute hemodynamic results and procedural complications. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;17(2):485–91. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(10)80120-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Percutaneous balloon aortic valvuloplasty. Acute and 30-day follow-up results in 674 patients from the NHLBI Balloon Valvuloplasty Registry. Circulation. 1991;84(6):2383–97. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.84.6.2383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Otto CM, Mickel MC, Kennedy JW, Alderman EL, Bashore TM, Block PC, Brinker JA, Diver D, Ferguson J, Holmes DR., Jr. Three-year outcome after balloon aortic valvuloplasty. Insights into prognosis of valvular aortic stenosis. Circulation. 1994;89(2):642–50. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.2.642. and others. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O'Keefe JH, Jr., Vlietstra RE, Bailey KR, Holmes DR., Jr. Natural history of candidates for balloon aortic valvuloplasty. Mayo Clin Proc. 1987;62(11):986–91. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)65068-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ross J, Jr., Braunwald E. Aortic stenosis. Circulation. 1968;38(1 Suppl):61–7. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.38.1s5.v-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pedersen WR, Klaassen PJ, Boisjolie CR, Pierce TA, Harris KM, Lesser JR, Hara H, Mooney MR, Graham KJ, Kshettry VR. Feasibility of transcatheter intervention for severe aortic stenosis in patients >or=90 years of age: aortic valvuloplasty revisited. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2007;70(1):149–54. doi: 10.1002/ccd.21161. and others. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hara H, Pedersen WR, Ladich E, Mooney M, Virmani R, Nakamura M, Feldman T, Schwartz RS. Percutaneous balloon aortic valvuloplasty revisited: time for a renaissance? Circulation. 2007;115(12):e334–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.657098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharifi M, Parhizgar A, Mehdipour M, Hodge M, Neckels B, Emrani F. Percutaneous balloon aortic valvuloplasty: a new look at an old procedure: a case report. Angiology. 2006;57(6):724–8. doi: 10.1177/0003319706295518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Don CW, Witzke C, Cubeddu RJ, Herrero-Garibi J, Pomerantsev E, Caldera AE, McCarty D, Inglessis I, Palacios IF. Comparison of procedural and in-hospital outcomes of percutaneous balloon aortic valvuloplasty in patients >80 years versus patients < or =80 years. Am J Cardiol. 105(12):1815–20. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.01.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kapadia SR, Goel SS, Yuksel U, Agarwal S, Pettersson G, Svensson LG, Smedira NG, Whitlow PL, Lytle BW, Tuzcu EM. Lessons Learned from Balloon Aortic Valvuloplasty Experience from the Pre-transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation Era. J Interv Cardiol. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8183.2010.00577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nashef SA, Roques F, Michel P, Gauducheau E, Lemeshow S, Salamon R. European system for cardiac operative risk evaluation (EuroSCORE) Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1999;16(1):9–13. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(99)00134-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roques F, Nashef SA, Michel P, Gauducheau E, de Vincentiis C, Baudet E, Cortina J, David M, Faichney A, Gabrielle F. Risk factors and outcome in European cardiac surgery: analysis of the EuroSCORE multinational database of 19030 patients. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1999;15(6):816–22. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(99)00106-2. and others. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grossi EA, Schwartz CF, Yu PJ, Jorde UP, Crooke GA, Grau JB, Ribakove GH, Baumann FG, Ursumanno P, Culliford AT. High-risk aortic valve replacement: are the outcomes as bad as predicted? Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;85(1):102–6. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.05.010. and others. discussion 107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dewey TM, Brown D, Ryan WH, Herbert MA, Prince SL, Mack MJ. Reliability of risk algorithms in predicting early and late operative outcomes in high-risk patients undergoing aortic valve replacement. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;135(1):180–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leontyev S, Walther T, Borger MA, Lehmann S, Funkat AK, Rastan A, Kempfert J, Falk V, Mohr FW. Aortic valve replacement in octogenarians: utility of risk stratification with EuroSCORE. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87(5):1440–5. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.01.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vahanian A, Alfieri O, Al-Attar N, Antunes M, Bax J, Cormier B, Cribier A, De Jaegere P, Fournial G, Kappetein AP. Transcatheter valve implantation for patients with aortic stenosis: a position statement from the European Association of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), in collaboration with the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI) Eur Heart J. 2008;29(11):1463–70. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn183. and others. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roques F, Michel P, Goldstone AR, Nashef SA. The logistic EuroSCORE. Eur Heart J. 2003;24(9):881–2. doi: 10.1016/s0195-668x(02)00799-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gorlin R, Gorlin SG. Hydraulic formula for calculation of the area of the stenotic mitral valve, other cardiac valves, and central circulatory shunts. I. Am Heart J. 1951;41(1):1–29. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(51)90002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akaike H. A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans Automat Contr. 1974;19(6):716–723. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greiner M, Pfeiffer D, Smith RD. Principles and practical application of the receiver-operating characteristic analysis for diagnostic tests. Prev Vet Med. 2000;45(1–2):23–41. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5877(00)00115-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lemeshow S, Hosmer DW., Jr. A review of goodness of fit statistics for use in the development of logistic regression models. Am J Epidemiol. 1982;115(1):92–106. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Team RDC . R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Satistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bhatti F, Grayson AD, Grotte G, Fabri BM, Au J, Jones M, Bridgewater B. The logistic EuroSCORE in cardiac surgery: how well does it predict operative risk? Heart. 2006;92(12):1817–20. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2005.083204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karthik S, Srinivasan AK, Grayson AD, Jackson M, Sharpe DA, Keenan DJ, Bridgewater B, Fabri BM. Limitations of additive EuroSCORE for measuring risk stratified mortality in combined coronary and valve surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2004;26(2):318–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2004.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim YH, Ahn JM, Park DW, Lee BK, Lee CW, Hong MK, Kim JJ, Park SW, Park SJ. EuroSCORE as a predictor of death and myocardial infarction after unprotected left main coronary stenting. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98(12):1567–70. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Romagnoli E, Burzotta F, Trani C, Siviglia M, Biondi-Zoccai GG, Niccoli G, Leone AM, Porto I, Mazzari MA, Mongiardo R. EuroSCORE as predictor of in-hospital mortality after percutaneous coronary intervention. Heart. 2009;95(1):43–8. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2007.134114. and others. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, McCulloch CE, Hsu CY. Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(13):1296–305. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van der Zee S, Baber U, Elmariah S, Winston J, Fuster V. Cardiovascular risk factors in patients with chronic kidney disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2009 doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2009.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ix JH, Shlipak MG, Katz R, Budoff MJ, Shavelle DM, Probstfield JL, Takasu J, Detrano R, O'Brien KD. Kidney function and aortic valve and mitral annular calcification in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;50(3):412–20. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Piers LH, Touw HR, Gansevoort R, Franssen CF, Oudkerk M, Zijlstra F, Tio RA. Relation of aortic valve and coronary artery calcium in patients with chronic kidney disease to the stage and etiology of the renal disease. Am J Cardiol. 2009;103(10):1473–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.01.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]