Abstract

With the recent development of siRNA and shRNA expression libraries, RNAi technology has been extensively employed to identify genes involved in diverse cellular processes, such as signal transduction, cell cycle, cancer biology and host-pathogen interactions. In the field of viral infection, this approach has already identified hundreds of new genes not previously known to be important for various virus lifecycles. In this brief review, we focus on recent studies performed using genome-wide RNAi-based screens in mammalian cells for the identification of essential host factors for viral infection and pathogenesis.

Keywords: siRNA, shRNA, HIV, genome-wide screening, virus replication

Introduction

Viruses are intracellular parasites that exploit host cell machineries in every step of their lifecycles.1,2 In recent years, it has become clear that human cells conserve the RNAi machinery found across plant and animal kingdoms.3 The RNA-dependant gene-silencing process was initially described for the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans wherein double stranded RNAs can trigger the cleavage and subsequent degradation of sequence homologous mRNA transcripts.4 Indeed, increasing amounts of experimental findings are consistent with the RNAi mechanism being employed by human cells to restrict viral infections.5–10 Accordingly, viruses have evolved RNAi suppressors,11–18 which may serve to change the small non-coding RNA profile in virus infected host cells.19–21

The conservation of RNAi-machinery in human cells has allowed for the development of RNAi-based genome-wide screening techniques to identify and investigate the cellular factors involved in viral replication and pathogenesis. Originally developed in C Elegans and Drosophila using long dsRNA,22–25 large-scale RNAi screens have been successfully applied using either synthetic short interfering RNAs (siRNAs) or vector-expressed short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) for mammalian cells.26–31 Genome-scale RNAi screens in mammalian cells have been performed for studies in cancer biology and host-pathogen interactions.32–44

Here, we review in brief the extant experience of RNAi based screens using siRNAs and shRNAs to study the cell factors used by various viruses for replication in host cells.

siRNA and shRNA methods for RNAi-based genome-wide screens

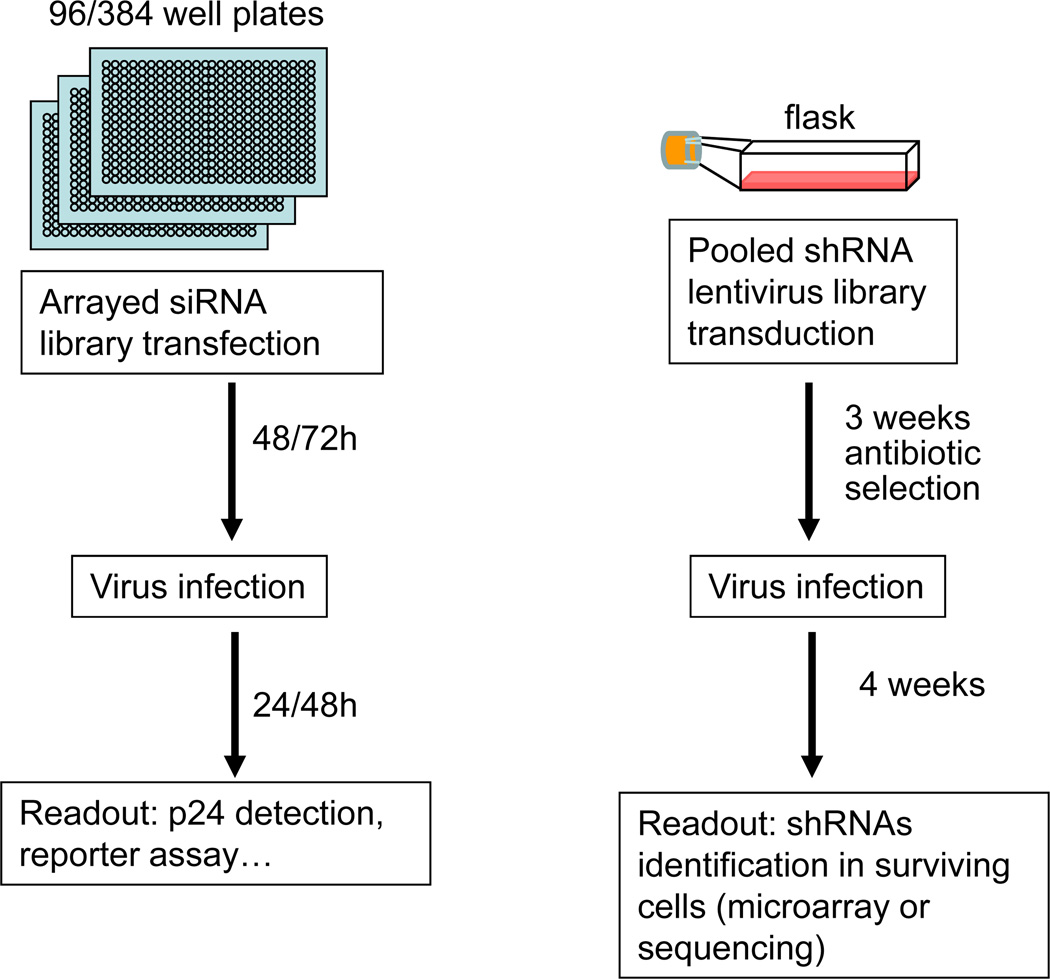

Two methodological approaches have been applied commonly for RNAi-based genome screenings --- large scale transfections using a synthetic siRNA library or viral transduction of a shRNA library into cells (Figure 1). These two methods are typically performed using two different formats. The application of siRNA libraries is usually performed in a cell-based array (commonly in 96 or 384 well microtiter plates), in which individual genes are silenced in each well. On the other hand, the shRNA library is applied in a pooled format, where the entire library is introduced into cells and a subsequent selection and/or screening read out is employed in bulk. Both of these approaches have been successfully used to study different biological processes, and each has advantages and disadvantages.

Figure 1. Schematics of the 2 different assay formats used in RNAi-based genome-wide screens.

The arrayed format used with siRNA libraries (left) and the pooled format used with shRNA libraries (right) are represented. The timing of the specific steps is indicated.

In the arrayed format, the siRNAs are transfected into cells, and the detection of the assay is monitored by individual readouts from each well (e.g. colorimetric, fluorescence or luminescence plate reading). The advantage of this assay is that the plate format facilitates high throughput manipulations, and that the identity of the gene candidate is directly given by the position on the plate. Moreover, several parameters can be evaluated for each well or targeted gene. However, when a large number of genes are targeted in a genome-scale analysis, numerous plates must be screened in a “labor-intensive” manner which would require the use of robotic machines. Also, because the siRNA-based screenings are transfection-based, this approach can be applied best to cells that are easily transfected, and thus the approach may not be useful for studies that require primary cells which are often difficult to transfect.

In a separate approach, retroviral vectors expressing shRNAs packaged into lentiviral particles are used to constitute a shRNA library that can be transduced into cells in a pooled format.27,28 These particles can be employed to stably transduce target cells, and the cells can be enriched by the selection of a co-transduced drug marker. shRNA-transduced cells can then be infected by virus, and the resulting outcome can be phenotypically characterized. For example in a recent assay, cells that survived lytic infection by HIV-1 represented those that have received a shRNA which has knocked down a cellular protein needed for intracellular HIV-1 replication.34 Alternatively, depending on how the assay is set up, infected cells could be isolated using fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) or other readouts. Thus, in a shRNA screening focused on kinases and phosphatases genes, Rato et al. used FACS to eliminate HIV infected cells and selected for cells which are resistant to HIV.45 In this way, they were able to implicate specific cellular kinases and phosphatases that act in the HIV-1 lifecycle. In the shRNA-library transduction approach, the shRNAs resident in the selected cells can then be amplified by PCR followed by sequencing or microarray hybridization for direct identification. An advantage of the shRNA-transduction approach using lentiviral particles instead of transfection is that transduction can introduce genetic material into a much larger range of dividing and non-dividing cells. Hence, this method is amenable for studying primary cells that may otherwise be refractory to transfection. Pooled shRNA screenings are also more easily conducted by most laboratories because this type of screening can generally be successfully executed without the need for expensive robotic tools.

RNAi-based genome-wide screens applied to host-virus interactions studies

Genomewide screenings in mammalian cells have been used for HIV34,39,42,43, influenza viruses,32,33,38 West Nile virus,41 hepatitis C virus,35,37 amongst others. We discuss in brief some of these screenings below.

HIV

In the literature, there are currently four studies of genome-wide screenings for host cell factors that are important for HIV-1 gene expression and replication (Table 1).34,39,42,43 Out of the four HIV screens, 3 were performed using siRNAs.39,42,43 Two of these used siRNA transfection into HeLa cells engineered to express the viral receptor CD4 followed by infection with virus.39,43 Thus, Brass et al. investigated early and late steps of HIV life cycle (from viral entry to virus budding and infectivity), and identified 273 genes out of a total of 20,000 mRNAs that were knocked down.43 By comparison, Zhou et al. used a similar strategy and found 232 candidate genes.39 Surprisingly, between the two studies only 15 genes overlapped. A third study by Konig et al. focused only on the early steps of HIV life cycle, from uncoating to protein synthesis.42 This system differed from the previous two screenings in its use of 293T cells instead of HeLa, and in the use of a virus pseudotyped with vesicular stomatitis virus G protein. Not surprisingly, of the 295 genes identified, very limited overlap was observed between this work,42 and the two other studies.39,43

Table 1.

genome-wide RNAi based screens for viral host factors in mammalian cells.

| Virus | cells | Assay readout | Candidate genes / genes tested (Reagent) |

Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV | ||||

| HIV-1 (IIIB) | HeLa (CD4+, BGal reporter) | p24; reporter activation | 273/21,121 (siRNA) | 43 |

| HIV-1 (HXB2) | HeLa (CD4+, BGal reporter) | Reporter activation | 232/19,709 (siRNA) | 39 |

| HIV-1 Luc vector, VSV-G pseudotyped | 293T | Luc reporter | 295/19,628 (siRNA) | 42 |

| HIV-1 (NL4.3) | Jurkat | Cell survival | 252/54,509 (shRNA) | 34 |

| INFLUENZA | ||||

| A/Puerto Rico/8/34 (H1N1; PR8) | Osteosarcoma cells (U2OS) | HA expression | 133/17,877 (siRNA) | 38 |

| Recombinant WSN (HA-Luc) | Human lung cells (A549) | Luciferase activity | 295/19,628 (siRNA) | 32 |

| A/WSN/33 (H1N1) | Human lung cells (A549) | NP staining; Luc reporter | 287/22,843 (siRNA) | 33 |

| HCV | ||||

| HCV (1b Luc replicon) | Huh7/Rep-Feo | Luc reporter | 96/21,094 (siRNA) | 35 |

| HCV (JFH-1 genotype 2a) | Human hepatocellular cell line (Huh 7.5.1) | Core 6G7 protein staining | 262/19,470 (siRNA) | 37 |

| WNV | ||||

| WNV (2471) DENV (NGC) | HeLa | Viral E-protein staining | 305 (WNV)/21,121 (siRNA) (124 shared with DENV) | 41 |

DENV: Dengue virus; HA: Hemagglutinin; VSV-G: Vesicular stomatitis virus G protein; WNV: West Nile virus.

The lack of overlap between these three screenings illustrates that in different settings different genes may be limiting for HIV-1 replication. The issue then becomes how does one interpret meaningfully these divergent findings.46,47 Bushman et al. attempted a meta-analysis to integrate the three siRNAs screens together with data obtained from other methods.48 The analyses showed that variations between replicates, between time points and between filtering thresholds all likely contributed to the differences observed between the siRNA screens. A take-home message appears to be that the various studies converge more at identifying relevant cellular pathways rather than at identifying the exact same genes within a commonly identified pathway.46

A fourth HIV study was performed by Yeung et al. using a shRNA library transduced into cells in a pooled format.34 The shRNA screening employed transduction instead of transfection; thus the investigators could use suspension Jurkat human T-cells which is a more physiological target cell model for HIV-infection than the adherent HeLa and 293T cells used in the three siRNA screens. The shRNA approach also allows for stable durable knock down of cellular mRNAs over an extended time period. Thus indirect apparent effects on viral replication due to cytotoxicity from the knock down of certain genes are less likely to emerge as false positive candidates in the shRNA- than the siRNA- screening. In the approach performed by Yeung et al., cells were transduced with a shRNA library that target 54,509 human transcripts, and then the cells were selected over 3 weeks with puromycin for those that have stably taken up a shRNA. [Each shRNA in the library was marked with a puromycin-resistance gene.] At this stage, the analysis of puromycin selected cells by Yeung et al. showed that only shRNA clones targeting 9,357 genes out of the starting 54,509 were still represented in the surviving cells. This result suggested that only 18.2% of the cell’s total transcripts can be tolerably knocked down without affecting Jurkat cell viability in tissue culture. A corollary of this finding is that the extended knock down of 82% of cellular transcripts is cytotoxic to cells in tissue culture. The puromycin-resistant cells were then infected for an additional 4 weeks with HIV-1, and cells that survived lytic infection by the virus were analyzed for their shRNA content. The microarray hybridization results showed that shRNAs targeting 252 distinct transcripts were enriched between 2 to 22 fold in the survivor cells. These transcripts represent candidate cellular factors that contribute to HIV-1 replication in Jurkat cells. Of course, further detailed functional validations are needed before one can understand how each gene affects HIV-1 propagation in Jurkat cells. It should be noted that because their approach differed in both duration of selection and cell type which was employed, not unexpectedly, Yeung et al. observed only minimal overlap with genes identified in the other three siRNA studies.39,42,43 Nevertheless, there was significant concordance in the pathways identified as important by Yeung et al.,34 and those identified earlier.46 By combining the results of these 4 studies, 40 genes were found common to at least 2 of the 4 screens (Table 2).

Table 2.

List of genes detected in at least 2 of the genome-wide RNAi-based screenings listed in table 1 for HIV, influenza and HCV.

| HIV | Influenza | HCV | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADRBK1 | MED28 | AHCYL1 | JUN | RPS16 | ARCN1 |

| AKT1 | MED4 | AIG1 | KIAA0652 | RUNX1 | CEBPD |

| ANAPC2 | MED6 | ARCN1 | KPNB1 | SF3A1 | COPA |

| ANKRD30A2 | MED7 | ATP6AP1 | LRP1B | SF3B1 | COPB1 |

| CAV2 | MID11P1 | ATP6AP2 | LY6G6C | SF3B14 | CTSF |

| CCNT1 | MRE11A | ATP6V0B | MAP2K3 | SNRP70 | DLK1 |

| CD4 | NFKB1 | ATP6V0C | MDM2 | TNK2 | DLX6 |

| CH5T1 | NUP153 | ATP6V0D1 | NHP2L1 | TRIM28 | HAS1 |

| CTDP1 | NUP98 | ATP6V1A | NUP98 | WDR18 | IDS |

| CXCR4 | RAB11 | ATP6V1B2 | NXF1 | ITGA7 | |

| DDX3X | RAB28 | BZRAP1 | OPRS1 | NOP5/NOP58 | |

| DMXL1 | RANBP2 | CD81 | PHF2 | NUAK2 | |

| EPAS1 | RELA | CLK1 | PIP5K1C | PI4KA | |

| HMCN2 | RGPD8 | COPA | PLK3 | RABEPK | |

| IBTK | RNF26 | COPB2 | PPP1R14D | TRIM62 | |

| IDH1 | RPL3 | COPG | PRPF8 | ||

| JAK1 | TCEB3 | FKBP8 | PTPRN | ||

| MAP4 | TNPO3 | IGSF1 | PTS | ||

| MED14 | TRIM55 | IKBKE | RACGAP1 | ||

| MED19 | WNK1 | IL17RA | RPS10 | ||

In bold are the genes detected in more than 2 screens of the same virus. In red are the genes common between 2 different viruses.

Influenza

To date, 3 independent genome-wide RNAi screens in mammalian cells have been published on identifying host factors important for influenza virus replication. Two of these studies were performed using the same human lung cell line A549,32,33 and the third one used osteosarcoma cells.38 Whereas the study of Karlas et al. covered the entire viral replication cycle, from viral entry to budding, the other two studies were limited to the early and middle stages of the viral lifecycle, from virus entry to protein translation. By targeting more than 17,000 genes, they identified 120,38 295,32 and 287,33 human genes involved in influenza virus replication. As in the case of HIV, only minimal overlap was observed in the lists of candidates from these three studies, with a maximum of 32 overlapping genes between the screens conducted by Konig et al. and Karlas et al. and a total of 49 genes were found in at least 2 of the 3 screens (Table 2).

As was done for the HIV-1 analyses, Watanabee et al. combined the results of these three influenza virus studies in a meta-analysis with data obtained from other methods, and finally arrived at a list of 128 human genes common to at least 2 genome-wide screens.49 Bioinformatics analysis of these genes revealed that they formed clusters of several proteins involved in similar host cellular functions important for the influenza virus life cycle, such as endocytosis, nuclear transport and translation initiation.

Other viruses

Genome-wide siRNA based screenings have been used in the study of two other viruses, West Nile virus (WNV) and Hepatitis C virus (HCV).Krishnan et al. recently identified 305 host factors that influence infection by WNV, with 283 factors facilitating and 22 antagonizing virus infection.41 Interestingly, the study also revealed that the silencing of 36% of the host factors used by WNV also reduced infection by Dengue Virus, a related flavivirus.

Two studies concerning HCV were recently published (Table 1). Tail et al. reported 96 genes candidates for HCV virus replication using a subgenomic replicon system.35 However, the replicon system was not able to address the full HCV lifecycle. Using a different system recapitulating the complete lifecycle of the virus, Li et al. identified 262 host factors important for HCV replication.37 Over 30 of the genes were previously implicated in the replication of HCV or West Nile virus (WNV, a related flavivirus) using functional genomic studies. A comparison of Li et al. with the work of Tail et al. performed with HCV replicon system showed an overlap of 15 genes out of 96 identified (Table 2).35 Interestingly, when compared with the host factors identified for HIV, the analysis revealed 10 common factors needed for the replication of both HIV and HCV. This is of particular interest considering that an estimated 25–30% of HIV-infected individuals are chronically co-infected with HCV.50

CONCLUSION

Genome-wide RNAi-based screening represents a powerful new approach for the identification of host factors involved in virus life-cycle. To date, at least several hundreds potential candidate genes have been identified in the few screenings discussed here for the various viruses. Moreover, considering that there was only limited concordance between the different screenings, this suggests that viral infection in varying setting may be limited by different factors. Thus the picture for “required” cellular factors for virus replication in human cells may be quite complex. Accordingly, future screenings will likely identify several hundreds more candidates, each specific for divergent scenarios. An ultimate goal is for investigators to carefully validate the mechanism whereby each identified candidate assists/detracts viral infection.

By comparing the list of factors identified for different types of viruses, we appreciate only a few common factors (Table 2). This is not surprising considering the poor overlap observed between independent screens conducted for the same virus. However, if data sets for each virus could be accrued that analyze different cell types and different settings of infection and if more studies could be extended to additional viruses, then the ever larger list of genes could reveal informative patterns to tell which are factors common to many viruses and which are factors specific to individual viruses (under defined conditions).

The study by Yeung et al. for HIV-1 is the first genome-wide screen for host factors involved in virus infection using shRNA vectors in a pooled format.34 This method seems promising because it broadens the amenable range of cells for functional analyses which could otherwise be limited only to cells that are easily transfectible by siRNAs. Thus shRNA-based lentiviral transductions could potentially be performed in physiologically relevant primary target cells. Moreover, the transduction approach offers numerous versatilities such as the use of shRNA library under inducible expression and the use of cell sorting after selection of transduced cells for phenotypical readouts.

By accelerating the discovery of new host factors important for the virus replication, genome-wide RNAi-based screens will undoubtedly reveal new therapeutic targets. The next few years promise to be exciting and productive.

Acknowledgements

Work in KTJ’s laboratory is supported by intramural funds from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and by funds from the Intramural AIDS Targeted Antiviral Program (IATAP) from the office of the Director, NIH.

Footnotes

Authors contribution

LH and KTJ wrote the paper together. Each author reviewed and edited the writing and approved its submission.

Contributor Information

Laurent Houzet, Email: houzetl@niaid.nih.gov.

Kuan-Teh Jeang, Email: kj7e@nih.gov.

REFERENCES

- 1.Goff SP. Host factors exploited by retroviruses. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:253–263. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lever AM, Jeang KT. Replication of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 from entry to exit. Int J Hematol. 2006;84:23–30. doi: 10.1532/IJH97.06112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cerutti H, Casas-Mollano JA. On the origin and functions of RNA-mediated silencing: from protists to man. Curr Genet. 2006;50:81–99. doi: 10.1007/s00294-006-0078-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fire A, Xu S, Montgomery MK, Kostas SA, Driver SE, Mello CC. Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 1998;391:806–811. doi: 10.1038/35888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Song L, Liu H, Gao S, Jiang W, Huang W. Cellular MicroRNAs Inhibit Replication of the H1N1 Influenza A Virus in Infected Cells. J Virol. 2010 doi: 10.1128/JVI.00456-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ellis-Connell AL, Iempridee T, Xu I, Mertz JE. Cellular MicroRNAs 200b and 429 Regulate the Epstein-Barr Virus Switch Between Latency and Lytic Replication. J Virol. 2010 doi: 10.1128/JVI.00923-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang X, Ye L, Hou W, Zhou Y, Wang YJ, Metzger DS, Ho W. Cellular microRNA expression correlates with susceptibility of monocytes/macrophages to HIV-1 infection. Blood. 2009;113:671–674. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-09-175000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nathans R, Chu CY, Serquina AK, Lu CC, Cao H, Rana TM. Cellular microRNA and P bodies modulate host-HIV-1 interactions. Mol Cell. 2009;34:696–709. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahluwalia JK, Khan SZ, Soni K, Rawat P, Gupta A, Hariharan M, Scaria V, Lalwani M, Pillai B, Mitra D, Brahmachari SK. Human cellular microRNA hsa-miR-29a interferes with viral nef protein expression and HIV-1 replication. Retrovirology. 2008;5:117. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-5-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang J, Wang F, Argyris E, Chen K, Liang Z, Tian H, Huang W, Squires K, Verlinghieri G, Zhang H. Cellular microRNAs contribute to HIV-1 latency in resting primary CD4+ T lymphocytes. Nat Med. 2007;13:1241–1247. doi: 10.1038/nm1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karjee S, Minhas A, Sood V, Ponia SS, Banerjea AC, Chow VT, Mukherjee SK, Lai SKl. The 7a accessory protein of SARS-CoV acts as a RNA silencing suppressor. J Virol. 2010;84:10395–10401. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00748-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schnettler E, de Vries W, Hemmes H, Haasnoot J, Kormelink R, Goldbach R, Berkhout B. The NS3 protein of rice hoja blanca virus complements the RNAi suppressor function of HIV-1 Tat. EMBO Rep. 2009;10:258–263. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qian S, Zhong X, Yu L, Ding B, de Haan P, Boris-Lawrie K. HIV-1 Tat RNA silencing suppressor activity is conserved across kingdoms and counteracts translational repression of HIV-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:605–610. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806822106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Vries W, Haasnoot J, Fouchier R, de Haan P, Berkhout B. Differential RNA silencing suppression activity of NS1 proteins from different influenza A virus strains. J Gen Virol. 2009;90:1916–1922. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.008284-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Vries W, Berkhout B. RNAi suppressors encoded by pathogenic human viruses. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:2007–2012. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haasnoot J, de Vries W, Geutjes EJ, Prins M, de Haan P, Berkhout B. The Ebola virus VP35 protein is a suppressor of RNA silencing. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e86. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bennasser Y, Yeung ML, Jeang KT. HIV-1 TAR RNA subverts RNA interference in transfected cells through sequestration of TAR RNA-binding protein, TRBP. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:27674–27678. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C600072200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bennasser Y, Le SY, Benkirane M, Jeang KT. Evidence that HIV-1 encodes an siRNA and a suppressor of RNA silencing. Immunity. 2005;22:607–619. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Houzet L, Yeung ML, de Lame V, Desai D, Smith SM, Jeang KT. MicroRNA profile changes in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) seropositive individuals. Retrovirology. 2008;5:118. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-5-118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Triboulet R, Mari B, Lin YL, Chable-Bessia C, Bennasser Y, Lebrigand K, Cardinaud B, Maurin T, Barbry P, Baillat V, Reynes J, Corbeau P, Jeang KT, Benkirane M. Suppression of microRNA-silencing pathway by HIV-1 during virus replication. Science. 2007;315:1579–1582. doi: 10.1126/science.1136319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yeung ML, Bennasser Y, Myers TG, Jiang G, Benkirane M, Jeang KT. Changes in microRNA expression profiles in HIV-1-transfected human cells. Retrovirology. 2005;2:81. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-2-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tabara H, Grishok A, Mello CC. RNAi in C. elegans: soaking in the genome sequence. Science. 1998;282:430–431. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5388.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clemens JC, Worby CA, Simonson-Leff N, Muda M, Maehama T, Hemmings BA, Dixon JE. Use of double-stranded RNA interference in Drosophila cell lines to dissect signal transduction pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:6499–6503. doi: 10.1073/pnas.110149597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fraser AG, Kamath RS, Zipperlen P, Martinez-Campos M, Sohrmann M, Ahringer J. Functional genomic analysis of C. elegans chromosome I by systematic RNA interference. Nature. 2000;408:325–330. doi: 10.1038/35042517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kamath RS, Fraser AG, Dong Y, Poulin G, Durbin R, Gotta M, Kanapin A, Le Bot N, Moreno S, Sohrmann M, Welchman DP, Zipperlen P, Ahringer J. Systematic functional analysis of the Caenorhabditis elegans genome using RNAi. Nature. 2003;421:231–237. doi: 10.1038/nature01278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elbashir SM, Harborth J, Lendeckel W, Yalcin A, Weber K, Tuschl T. Duplexes of 21-nucleotide RNAs mediate RNA interference in cultured mammalian cells. Nature. 2001;411:494–498. doi: 10.1038/35078107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berns K, Hijmans EM, Mullenders J, Brummelkamp TR, Velds A, Heimerikx M, Kerkhoven RM, Madiredjo M, Nijkamp W, Weigelt B, Agami R, Ge W, Cavet G, Linsley PS, Beijersbergen RL, Bernards R. A large-scale RNAi screen in human cells identifies new components of the p53 pathway. Nature. 2004;428:431–437. doi: 10.1038/nature02371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paddison PJ, Silva JM, Conklin DS, Schlabach M, Li M, Aruleba S, Balija V, O'Shaughnessy A, Gnoj L, Scobie K, Chang K, Westbrook T, Cleary M, Sachidanandam R, McCombie WR, Elledge SJ, Hannon GJ. A resource for large-scale RNA-interference-based screens in mammals. Nature. 2004;428:427–431. doi: 10.1038/nature02370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Echeverri CJ, Perrimon N. High-throughput RNAi screening in cultured cells: a user's guide. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:373–384. doi: 10.1038/nrg1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boutros M, Ahringer J. The art and design of genetic screens: RNA interference. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:554–566. doi: 10.1038/nrg2364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mohr S, Bakal C, Perrimon N. Genomic screening with RNAi: results and challenges. Annu Rev Biochem. 2010;79:37–64. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060408-092949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Konig R, Stertz S, Zhou Y, Inoue A, Hoffmann HH, Bhattacharyya S, Alamares JG, Tscherne DM, Ortigoza MB, Liang Y, Gao Q, Andrews SE, Bandyopadhyay S, De Jesus P, Tu BP, Pache L, Shih C, Orth A, Bonamy G, Miraglia L, Ideker T, García-Sastre A, Young JA, Palese P, Shaw ML, Chanda SK. Human host factors required for influenza virus replication. Nature. 2010;463:813–817. doi: 10.1038/nature08699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karlas A, Machuy N, Shin Y, Pleissner KP, Artarini A, Heuer D, Becker D, Khalil H, Ogilvie LA, Hess S, Mäurer AP, Müller E, Wolff T, Rudel T, Meyer TF. Genome-wide RNAi screen identifies human host factors crucial for influenza virus replication. Nature. 2010;463:818–822. doi: 10.1038/nature08760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yeung ML, Houzet L, Yedavalli VS, Jeang KT. A genome-wide short hairpin RNA screening of jurkat T-cells for human proteins contributing to productive HIV-1 replication. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:19463–19473. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.010033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tai AW, Benita Y, Peng LF, Kim SS, Sakamoto N, Xavier RJ, Chung RT. A functional genomic screen identifies cellular cofactors of hepatitis C virus replication. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5:298–307. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Luo J, Emanuele MJ, Li D, Creighton CJ, Schlabach MR, Westbrook TF, Wong KK, Elledge SJ. A genome-wide RNAi screen identifies multiple synthetic lethal interactions with the Ras oncogene. Cell. 2009;137:835–848. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li Q, Brass AL, Ng A, Hu Z, Xavier RJ, Liang TJ, Elledge SJ. A genome-wide genetic screen for host factors required for hepatitis C virus propagation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:16410–16415. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907439106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brass AL, Huang IC, Benita Y, John SP, Krishnan MN, Feeley EM, Ryan BJ, Weyer JL, van der Weyden L, Fikrig E, Adams DJ, Xavier RJ, Farzan M, Elledge SJ. The IFITM proteins mediate cellular resistance to influenza A H1N1 virus, West Nile virus, and dengue virus. Cell. 2009;139:1243–1254. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou H, Xu M, Huang Q, Gates AT, Zhang XD, Castle JC, Stec E, Ferrer M, Strulovici B, Hazuda DJ, Espeseth AS. Genome-scale RNAi screen for host factors required for HIV replication. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;4:495–504. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Luo B, Cheung HW, Subramanian A, Sharifnia T, Okamoto M, Yang X, Hinkle G, Boehm JS, Beroukhim R, Weir BA, Mermel C, Barbie D, Awad T, Zhou XC, Nguyen T, Piqani B, Li C, Golub T, Meyerson M, Hacohen N, Hahn WC, Lander ES, Sabatini DM, Root DE. Highly parallel identification of essential genes in cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:20380–20385. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810485105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krishnan MN, Ng A, Sukumaran B, Gilfoy FD, Uchil PD, Sultana H, Brass AL, Adametz R, Tsui M, Qian F, Montgomery RR, Lev S, Mason PW, Koski RA, Elledge SJ, Xavier RJ, Agaisse H, Fikrig E. RNA interference screen for human genes associated with West Nile virus infection. Nature. 2008;455:242–245. doi: 10.1038/nature07207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Konig R, Zhou Y, Elleder D, Diamond TL, Bonamy GM, Irelan JT, Chiang CY, Tu BP, De Jesus PD, Lilley CE, Seidel S, Opaluch AM, Caldwell JS, Weitzman MD, Kuhen KL, Bandyopadhyay S, Ideker T, Orth AP, Miraglia LJ, Bushman FD, Young JA, Chanda SK. Global analysis of host-pathogen interactions that regulate early-stage HIV-1 replication. Cell. 2008;135:49–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brass AL, Dykxhoorn DM, Benita Y, Yan N, Engelman A, Xavier RJ, Lieberman J, Elledge SJ. Identification of host proteins required for HIV infection through a functional genomic screen. Science. 2008;319:921–926. doi: 10.1126/science.1152725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Silva J, Chang K, Hannon GJ, Rivas FV. RNA-interference-based functional genomics in mammalian cells: reverse genetics coming of age. Oncogene. 2004;23:8401–8409. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rato S, Maia S, Brito PM, Resende L, Pereira CF, Moita C, Freitas RP, Moniz-Pereira J, Hacohen N, Moita LF, Goncalves J. Novel HIV-1 knockdown targets identified by an enriched kinases/phosphatases shRNA library using a long-term iterative screen in Jurkat T-cells. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9276. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kok KH, Lei T, Jin DY. siRNA and shRNA screens advance key understanding of host factors required for HIV-1 replication. Retrovirology. 2009;6:78. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-6-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goff SP. Knockdown screens to knockout HIV-1. Cell. 2008;135:417–420. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bushman FD, Malani N, Fernandes J, D'Orso I, Cagney G, Diamond TL, Zhou H, Hazuda DJ, Espeseth AS, König R, Bandyopadhyay S, Ideker T, Goff SP, Krogan NJ, Frankel AD, Young JA, Chanda SK. Host cell factors in HIV replication: meta-analysis of genome-wide studies. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000437. e1000437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Watanabe T, Watanabe S, Kawaoka Y. Cellular networks involved in the influenza virus life cycle. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;7:427–439. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Andersson K, Chung RT. Hepatitis C Virus in the HIV-infected patient. Clin Liver Dis. 2006;10:303–320. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2006.05.002. viii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]