Abstract

Background

The strong relationship between urinary albumin excretion (UAE) and pulse pressure (PP) in cross-sectional studies suggests that pressure pulsatility may contribute to renal microvascular injury. The longitudinal relationships between UAE and the various indices of blood pressure (BP) are not well studied. We compared the associations of UAE with the longitudinal burden of PP, systolic, diastolic, and mean BP.

Methods and Results

UAE was measured from 24-hour urine collections in 450 community-dwelling subjects (age=57±15 years, 53% women, all with UAE<200 µg/min). For each subject, longitudinal indices of BP were estimated by dividing the area under the curve of serial measurements of BP (median=5) during 1–22 years preceding UAE measurement by the number of follow-up years. Median [interquartile range] UAE was 4.7 [3.3–7.8] µg/min in women and 5.2 [3.7–9.8] µg/min in men. In women, UAE was not related to longitudinal indices of BP. In men, in multivariable-adjusted models that included either longitudinal systolic and diastolic BP, or longitudinal PP and mean BP, UAE was independently associated with systolic (β=0.227, P=0.03), but not with diastolic (β=−0.049, P=0.59) BP, and with PP (β=0.216, P=0.01), but not with mean BP (β=0.032, P=0.72). Comparisons of these two models and stepwise regression analyses both indicated that, of the four longitudinal indices of BP, PP was the strongest predictor of UAE in men.

Conclusion

Chronic exposure to high pressure pulsatility is a strong risk factor for hypertensive nephropathy. Future studies should examine whether PP reduction provides additional renoprotection beyond that conferred by conventional BP goals alone.

Keywords: Pulse Pressure, Albuminuria, Microvascular, Renal Function, Longitudinal Studies

Introduction

Urinary albumin excretion (UAE) is an early marker of glomerular injury and a well-established risk factor for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in diverse populations,1 even within the conventional “normal” range.2 Although increased UAE is a sign of glomerular injury, it has long been considered a marker of generalized vascular dysfunction,3 partially explaining the significant risk associated with increased UAE.1,2

Although the pathophysiologic factors that influence UAE have not been fully elucidated, a link between blood pressure (BP) and renal dysfunction in general,4 and UAE in particular,5 has long been recognized. Previous studies have uncovered significant associations between UAE and the 4 indices of BP, namely systolic BP (SBP), diastolic BP (DBP), pulse pressure (PP), and mean BP (MBP). Whereas some studies, especially earlier works, emphasized associations between UAE and DBP or MBP,6–8 more recent studies found stronger associations between UAE and SBP or PP.9–16

It is hypothesized that the high-flow, low-resistance arterial system of the kidneys and the unique arterial structure of the glomeruli contribute to BP-induced renal microvascular injury.17,18 In most systemic arterial territories, the precapillary resistance arterioles absorb the bulk of the pulsatile energy of the blood, thus shielding the microvasculature from excessively pulsatile pressure and flow. In contrast, in the kidneys, in order to maintain filtration pressure in the glomerulus, vascular resistance in the afferent arteriole is constantly maintained below that in the efferent arteriole, thus exposing the glomeruli to higher levels of pressure and flow pulsatility. Indeed, it is estimated that nearly half of the transmitted pulsatile energy is absorbed in the glomeruli.19 Notably, the myogenic response of the glomerular afferent arteriole, the mechanism that protects the kidneys from elevated BP, seems to primarily respond to changes in SBP, and is insensitive to changes in other indices of BP, including PP.20 Therefore, it may be hypothesized that, when BP is within the autoregulatory range, the pulsatile component of BP can still penetrate the glomeruli, where it can lead to renal microvascular injury.19 Thus, as a marker of glomerular injury, UAE would be expected to be more strongly associated with PP than with other indices of BP, including SBP.

Accordingly, the present longitudinal study was conducted in a community-dwelling sample of clinically healthy, normotensive and untreated hypertensive individuals with up to 22 years of follow-up. We hypothesized that a longitudinal index of PP would be a stronger predictor of UAE than other longitudinal indices of BP, namely, SBP, DBP and MBP.

Methods

Study Population

The study population was drawn from participants in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (BLSA), an ongoing, prospective, observational study of normative aging in community-dwelling volunteers. The BLSA was established in 1958 and has been described in detail elsewhere.21 Briefly, subjects, who are healthy at study entry, undergo approximately 2.5 days of medical examinations at the clinical research unit of the National Institute on Aging in Baltimore, Maryland at regular intervals.

Twenty four-hour urine collections were performed in participants who visited the study site between 1996 and 1999. The present analyses involved all BLSA volunteers who underwent UAE measurement, were free from macroalbuminuria (UAE >200 µg/min), had no clinical evidence of cardiovascular disease other than hypertension (defined as BP ≥140/90), and were not receiving medications for hypertension or diabetes mellitus.

Definition of Variables

UAE was measured with nephelometry (Beckman Array System, Brea, CA) in 24-hour urine samples collected onsite. Brachial BP was measured with conventional sphygmomanometry using an appropriately sized cuff and standard methods after at least 5 minutes of rest in the seated position. PP was calculated as [SBP − DBP] and MBP as [DBP + (PP/3)]. Blood glucose and circulating lipid concentrations were determined in samples drawn after an over-night fast using commercially available methods. Serum creatinine was not measured concurrent with UAE measurement. Therefore, in a subset of subjects in whom serum creatinine was measured during the visits immediately before and after the UAE measurement, serum creatinine at the time of UAE measurement was estimated with linear mixed effects models and an interpolation technique as previously described.22 Glomerular filtration rate was estimated using the estimated creatinine values and the 4-element Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) equation.23 White blood cell count was used as a crude measure of inflammation.

Longitudinal Variables

Cumulative exposure to all variables except age and height was estimated after the method used by Li et al,24 as previously described.25 Briefly, the area under the curve of serial measurements of each variable during visits preceding UAE measurement (median number of visits=5) was computed with linear mixed effects models and was used as a measure of cumulative exposure to that variable. The random effects included in the mixed effects models allowed the initial value of each variable (intercept) and its trajectory (slope) for each subject to vary from the corresponding population mean values. The area under the curve for each variable was then divided by the number of follow-up years for each subject to estimate the average cumulative exposure (the “longitudinal index”) for that variable.

Statistical Analysis

Variables with a skewed distribution (UAE and triglycerides) were log-transformed for analysis. Correlations between variables were assessed with Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r). Independent correlates of UAE were assessed with linear regression analyses. Variance inflation factors were monitored and were less than 4 in all models, ensuring lack of multicollinearity among the independent variables. Selection of covariates for inclusion in regression analyses were based on significant correlations in the present study or previously reported significant associations with UAE. When smoking was included in the models, it was not associated with UAE in any of the models. Therefore, smoking was removed from all models.

We used two different approaches to compare the strength of the associations between UAE and the longitudinal indices of BP. First, we used a linear regression model with a stepwise entry method that allowed all longitudinal indices of BP and other covariates to compete for entry into the model. Next, we constructed separate, non-nested models which were adjusted for the same set of covariates and differed only in that one included longitudinal SBP and DBP and the other included longitudinal PP and MBP. The combinations of SBP and DBP, or PP and MBP, were used so that both the steady and pulsatile components of BP are represented in each model. Model predictions were then formally compared with statistical methods appropriate for the comparison of non-nested models, namely J-test, Cox test and Encompassing test.26,27 These tests use three different approaches to examine two non-nested models to determine if one provides better predictions of a dependent variable than the other. Subsequently, we used a fast double bootstrap test28 to confirm the results of the comparisons of non-nested models. We also computed the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) for each model as a measure of goodness-of-fit.

Statistical analyses were performed using R 2.8.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), SPSS 14.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) and SAS 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Unless otherwise specified, descriptive statistics are expressed as mean ± SD for continuous variables and as N (%) for discrete variables. Statistical significance was inferred for P<0.05.

All participants provided written informed consent and the study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Institute on Aging. The authors had full access to the data and take responsibility for its integrity. All authors have read and agree to the manuscript as written.

Results

Characteristics of the Study Population

Characteristics of the 450 study subjects at the time of UAE measurement are summarized in Table-1. Women comprised nearly half of the study cohort, which predominantly included middle-aged, White subjects with a median follow-up of 4 years (range=1–22 years) and a BMI in the overweight range. Notably, UAE [median (interquartile range)] was well within the “normal” range in both men [5.2 (3.7–9.8) µg/min] and women [4.7 (3.3–7.8) µg/min] and only 9% of the men and 3% of the women in the study cohort had microalbuminuria (UAE=20–200 µg/min).

Table-1.

Characteristics of the study population at the time of UAE measurement

| Variable | Men (N=213) |

Women (N=237) |

|---|---|---|

| Duration of Follow-up (yr) | 8.0±5.6 | 4.2±2.8 |

| Demographics, Anthropometric Data | ||

| Age (yr) | 60±16 | 55±14 |

| Height (cm) | 176±7 | 163±7 |

| Weight (kg) | 85±14 | 69±14 |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 27±4 | 26±5 |

| White Race, N (%) | 181 (85) | 195 (82) |

| Ever Smoker, N (%) | 133 (62) | 99 (42) |

| Comorbidities and Medication Use | ||

| Hypertension, N (%) | 89 (42) | 65 (27) |

| Diabetes Mellitus,* N (%) | 2 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Lipid Lowering Drug Use, N (%) | 15 (7) | 7 (3) |

| Hemodynamic Data | ||

| Heart Rate (min−1) | 67±12 | 70±12 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure (mm Hg) | 131±20 | 125±21 |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure (mm Hg) | 82±11 | 77±11 |

| Pulse Pressure (mm Hg) | 50±17 | 48±16 |

| Mean Arterial Pressure (mm Hg) | 98±12 | 93±13 |

| Laboratory Data | ||

| Microalbuminuria,† N (%) | 19 (9) | 6 (3) |

| lnUAE (μg/min) | 1.88±0.83 | 1.67±0.62 |

| Fasting Blood Glucose (mg/dl) | 95±14 | 89±7 |

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 200±29 | 204±34 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 111±61 | 96±51 |

| White Blood Cell Count (ml−1) | 5,937±1,513 | 5,778±1,358 |

| eGFR‡ (ml/min/1.73 m2) | 89±50 | 80±23 |

Diet-controlled

Defined as UAE = 20–200 µg/min

eGFR: Estimated glomerular filtration rate at the time of UAE measurement, calculated with the 4-element MDRD equation; estimates of concurrent serum creatinine were available in 178 (84%) of the men and 184 (78%) of the women in the study cohort.

Association of UAE With Cross-Sectional Indices of BP

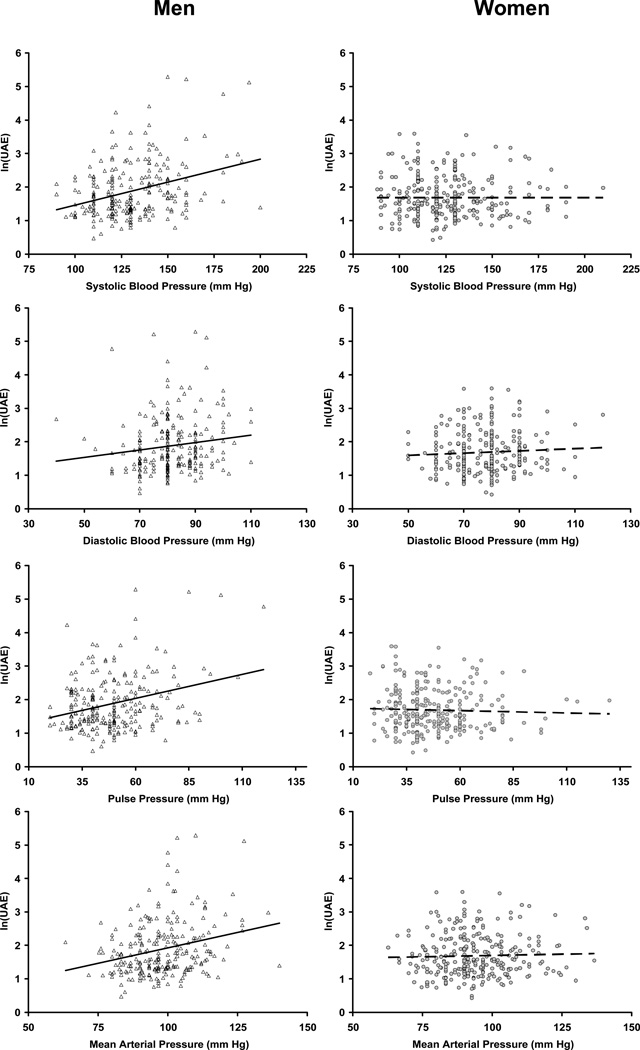

The Figure illustrates the relationships between UAE and the various cross-sectional indices of BP. In cross-sectional analyses with UAE as the dependent variable, the interactions of sex with both SBP and PP were highly significant (both P<0.001). Therefore, all analyses were performed separately in men and women.

Figure.

Urinary albumin excretion [log-transformed; ln(UAE)] was significantly related to all cross-sectional indices of blood pressure in men (left column, triangles, solid lines), but not in women (right column, circles, dashed lines). The best fit linear regression lines are shown.

In women, UAE did not correlate with any of the cross-sectional indices of BP (r=−0.02, 0.01, −0.04, and −0.01 for SBP, DBP, PP, and MBP, respectively, all P≥0.57). Therefore, no further analyses were pursued in women. Conversely, in men, UAE correlated significantly and positively with all cross-sectional indices of BP (r=0.33, 0.15, 0.29, and 0.27 for SBP, DBP, PP, and MBP, respectively, all P≤0.03), as well as with weight (P=0.23, P<0.001), heart rate (P=0.14, P=0.048) and fasting blood glucose (P=0.23, P<0.001). In cross-sectional analyses, data from men were analyzed in 2 separate models that were adjusted for the same set of covariates and included either SBP and DBP, or PP and MBP. In the model with SBP and DBP, UAE was significantly associated with SBP (standardized regression coefficient [β]=0.355, P<0.001), but not with DBP (β=−0.077, P=0.33). In the model with PP and MBP, UAE was significantly associated with PP (β=0.246, P=0.003), but not with MBP (β=0.127, P=0.09).

Association of UAE with Longitudinal Indices of BP

In women, UAE was not related to any of the longitudinal indices of BP (Table-2). Therefore, no further analyses were pursued in women. Conversely, in men, UAE correlated significantly and positively with all longitudinal indices of BP, as well as with weight, heart rate, and fasting blood glucose (Table-2). In longitudinal analyses with UAE as the dependent variable, the interactions of sex with both SBP and PP were significant (both P≤0.01). Therefore, all analyses were performed separately in men and women.

Table-2.

Longitudinal* correlates of UAE among men and women in the study cohort

| Variable | Men (N=213) |

Women (N=237) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | P | r | P | |

| Age* | 0.08 | 0.25 | −0.16 | 0.01 |

| Height* | 0.09 | 0.20 | 0.24 | 0.0003 |

| Weight | 0.22 | 0.001 | 0.17 | 0.009 |

| Heart Rate | 0.19 | 0.006 | −0.06 | 0.34 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure | 0.23 | 0.0006 | 0.01 | 0.84 |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure | 0.16 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.94 |

| Pulse Pressure | 0.23 | 0.0009 | 0.00 | 0.99 |

| Mean Blood Pressure | 0.22 | 0.002 | 0.01 | 0.88 |

| Total Cholesterol | 0.11 | 0.11 | −0.13 | 0.04 |

| ln(Triglycerides) | 0.11 | 0.11 | −0.08 | 0.228 |

| Fasting Glucose | 0.27 | <0.0001 | 0.15 | 0.02 |

| White Blood Cell Count | 0.09 | 0.21 | 0.03 | 0.66 |

Except for age and height, for which the reported statistics are computed for their values at the time of UAE measurement.

r: Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient

In men, longitudinal data were analyzed in 2 separate models similar to those described in the cross-sectional analyses above. In the model with SBP and DBP, UAE was significantly associated with SBP (β=0.227, P=0.03), but not with DBP (β=−0.049, P=0.59). In the model with PP and MBP, UAE was significantly associated with PP (β=0.216, P=0.01), but not with MBP (β=0.032, P=0.72) (Table-3, models A and B).

Table-3.

Longitudinal* determinants of UAE among men in the study cohort

| Model | A | B | C | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Model with SBP and DBP | Model with PP and MAP | Stepwise Model with SBP, DBP, PP and MAP |

||||||

| β | SE | P | β | SE | P | β | SE | P | |

| White Race | 0.041 | 0.167 | 0.57 | 0.030 | 0.165 | 0.67 | |||

| Age* (yr) | −0.029 | 0.005 | 0.73 | −0.029 | 0.004 | 0.72 | |||

| Height* (cm) | 0.092 | 0.009 | 0.25 | 0.099 | 0.009 | 0.21 | 0.134 | 0.008 | 0.04 |

| Weight (kg) | 0.065 | 0.006 | 0.45 | 0.078 | 0.006 | 0.36 | |||

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 0.070 | 0.002 | 0.34 | 0.054 | 0.002 | 0.47 | |||

| ln(Triglycerides) | −0.055 | 0.158 | 0.48 | −0.057 | 0.157 | 0.46 | |||

| Fasting Glucose (mg/dl) | 0.208 | 0.011 | 0.005 | 0.202 | 0.011 | 0.006 | 0.225 | 0.010 | 0.001 |

| White Blood Cell Count (ml−1) | 0.045 | 0.000 | 0.52 | 0.054 | 0.000 | 0.44 | |||

| Heart Rate (min−1) | 0.115 | 0.010 | 0.11 | 0.128 | 0.010 | 0.08 | 0.148 | 0.009 | 0.03 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure (mmHg) | 0.227 | 0.008 | 0.03 | … | … | … | |||

| Diastolic Blood Pressure (mmHg) | −0.049 | 0.013 | 0.59 | … | … | … | |||

| Pulse Pressure (mmHg) | … | … | … | 0.216 | 0.004 | 0.01 | 0.232 | 0.003 | 0.001 |

| Mean Blood Pressure (mmHg) | … | … | … | 0.032 | 0.011 | 0.72 | |||

Except for age and height, for which the reported statistics are computed for their values at the time of UAE measurement.

β: Standardized Regression Coefficient, SE: Standard Error

When the analyses were repeated with further adjustments for estimated glomerular filtration rate in the subset of men for whom serum creatinine was available (N=178), similar results were obtained (data not shown).

Comparisons of the Longitudinal Indices of BP as Predictors of UAE

To compare the strength of the associations between UAE and the 4 longitudinal indices of BP, we first used a stepwise model which allowed all indices of BP and other covariates to compete for entry into the model. As shown in Table-3, model C, PP was the only index of BP that entered the model.

Next, we used the J-test, the Cox test and the Encompassing test to directly compare the contributions of longitudinal SBP and DBP to those of longitudinal PP and MBP as predictors of UAE. Specifically, these tests compared models A and B in Table-3 to determine whether model A improved the predictions of UAE yielded by model B and vice versa. The results of all 3 tests indicated that the model with longitudinal SBP and DBP did not predict UAE better than the model with longitudinal PP and MBP (P=0.59, 0.54 and 0.59 for J-test, Cox test and Encompassing test, respectively). Conversely, the model with longitudinal PP and MBP provided better predictions of UAE compared to the model with longitudinal SBP and DBP (P=0.02, <0.001 and 0.02 for J-test, Cox test and Encompassing test, respectively). The results of the fast double bootstrap test also confirmed that the model with longitudinal SBP and DBP did not provide better predictions of UAE when compared to the model with longitudinal PP and MBP (P>0.10), whereas the model with longitudinal PP and MBP provided superior predictions of UAE when compared to the model with longitudinal SBP and DBP (P=0.007). Consistently, the model with longitudinal PP and MBP had a smaller AIC than the model with longitudinal SBP and DBP (1124 vs. 1126), indicating that the former provided a better fit of the data.

Considering that longitudinal DBP and MBP did not achieve statistical significance in any of the models, these results collectively suggested that among the longitudinal indices of BP, PP was the strongest predictor of UAE in men. This was confirmed when all analyses were repeated while deleting DBP and MBP from the regression models (data not shown).

Discussion

In the present study, we examined the associations between UAE and 4 longitudinal indices of BP in a community-dwelling sample of clinically healthy, normotensive and untreated hypertensive individuals. In women, UAE was not associated with any of the cross-sectional or longitudinal indices of BP. Conversely, in men, longitudinal SBP and PP were independent predictors of UAE, whereas longitudinal DBP and MBP were not. Comparative analyses indicated that among the 4 longitudinal indices of BP, PP was the strongest predictor of UAE in men.

Previous Comparisons of the Indices of BP as Predictors of Renal Injury

The association of UAE with the various indices of BP has been the subject of many prior studies.5–16 However, to date, only 1 study has compared the associations of UAE with the various indices of BP.9 In a cross-sectional study that only included men,9 Pedrinelli et al found that among the 4 indices of BP, PP was the best predictor of microalbuminuria (UAE≥15 µg/min). In another study,14 Tsakiris et al found that, after adjusting for age, spot urinary albumin concentration measured in a morning urine sample was significantly associated with concurrent SBP and PP, but not with concurrent DBP or MBP. Although, urinary albumin concentration had a stronger association with concurrent PP (β=0.199, P=0.00001) than with concurrent SBP (β=0.164, P=0.005), the associations of urinary albumin concentration with the 4 BP indices measured 3 and 12 years before urinary albumin measurement were inconsistent.14 Additionally, these associations were not directly compared in that study.14

Two other studies have compared the associations of worsening renal function with the various indices of BP.29,30 In a post-hoc analysis of data from the Reduction of Endpoints in NIDDM with the Angiotensin-II Antagonist Losartan (RENAAL) study,30 Bakris et al found that, in subjects with hypertension and established diabetic nephropathy, baseline PP was a better predictor of the primary composite outcome of doubling of serum creatinine, end-stage renal disease, or death than baseline SBP or DBP, and that SBP and PP were equivalent as predictors of incident end-stage renal disease.30 In contrast, in a subgroup of subjects from the placebo arm of the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP),29 Young et al found that baseline SBP was better than baseline PP in predicting a decline in kidney function, defined as a 0.4 mg/dl increase in serum creatinine, during 5 years of follow-up. It is noteworthy that both of these studies29,30 only used the baseline BP variables to predict the study outcomes. This is important because all subject in RENAAL30 and 44% of the subjects in the placebo arm of SHEP31 received antihypertensive medications, which would affect their BP during the course of the study.

The present study is the first to compare the relationships of UAE, a measure of renal microvascular injury, and the 4 longitudinal indices of BP. Our findings underscore the importance of the pulsatile component of BP as a risk factor for increased UAE and support the hypothesis that implicates pressure pulsatility in renal microvascular injury.17,18

Mechanistic Hypotheses That Link UAE to the Pulsatile Component of BP

Contemporary views suggest that the high-flow, low-resistance arterial system of the kidneys and the unique arterial structure of the glomeruli may play a major role in the pathogenesis of renal microvascular injury in hypertension.17,18 Specifically, in order to maintain glomerular filtration pressure, vascular resistance in the afferent arteriole is constantly maintained below that in the efferent arteriole. Thus, unlike most systemic arterial territories, where the precapillary resistance arterioles shield the microcirculation from excessive pressure pulsatility, the glomeruli are exposed to near-systemic levels of pulsatile pressure17 and nearly half of the pulsatile energy that is transmitted through the afferent arteriole is absorbed in the glomeruli.19 Further evidence for the vulnerability of glomeruli to pulsatile pressure comes from experimental studies of the myogenic response of the afferent arteriole, which is thought to be the primary mechanism that protects the glomeruli from BP-induced injury.20 Loutzenhiser et al found that this mechanism primarily responded to changes in SBP, whereas, when SBP was held constant, this renoprotective mechanism was insensitive to changes in the other indices of BP, including PP.20 Thus, it may be concluded that, whereas the glomeruli are shielded from SBP-induced barotrauma within the autoregulatory range of BP, they are not protected from the detrimental effects of PP.

Additional support for the role of PP in the pathogenesis of increased UAE comes from studies of the effects of PP on small artery structure and function. There is good evidence that among the various indices of BP, PP is most strongly correlated with small artery remodeling (e.g., increased media:lumen ratio).32,33 Interestingly, among the currently available classes of medications, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, which are the standard treatment for the reduction of UAE, also appear to be the most effective in reversing these small-artery structural abnormalities.34 Such structural changes are often accompanied by significant abnormalities in small artery function, including endothelial dysfunction,17,34 which is strongly linked to UAE.2,35

The strong association between UAE and generalized endothelial dysfunction suggests that glomerular endothelial dysfunction may play a causative role in the pathogenesis of increased UAE.2,35 Indeed, in an experimental study, endothelial dysfunction antedated the rise in UAE in hypertensive rats.36 Importantly, clinical studies indicate that endothelial dysfunction is more strongly associated with PP than with SBP,37 suggesting that endothelial cells may be more susceptible to oscillatory, than to peak, shear stress. Collectively, these findings support our results and suggest that the stronger association of UAE with longitudinal PP than with longitudinal SBP in the present study may be a manifestation of the stronger deleterious effects of chronic exposure to PP on endothelial function.

Sex-related Differences: Potential Explanations

Although the reasons for the lack of association between UAE and BP among the women in our cohort are not entirely clear, several observations may help to explain the sex-related discordance in our results. Compared to men, women in our cohort had a shorter duration of follow-up (P<0.001), significantly lower UAE (P=0.003), less microalbuminuria (P=0.009), and a lower global vascular risk burden (Table-1). Notably, sex-related differences in the incidence and severity of renal disease are not uncommon.38 Multiple studies have found higher levels of UAE in men than in women,13,39,40 which may be due to sex-related differences in endothelial function41 or glomerular hemodynamics.42

Clinical Implications

Previous studies have demonstrated that the association between UAE and the risk of adverse outcomes is linear, without any specific thresholds.43 Thus, identification of modifiable risk factors for low-grade UAE is important, especially vis-à-vis the rising prevalence of albuminuria.44 Our results suggest that, at least in men, chronic exposure to high PP can lead to higher UAE. This finding suggests that therapies that reduce central arterial stiffness may have superior renoprotective effects compared to therapies that reduce BP, but have a lesser impact on central arterial stiffness. Interestingly, the vasopeptidase inhibitor, omapatrilat, which was more effective than enalapril in reducing proximal aortic stiffness in humans,45 also produced a larger reduction in glomerular pressure and proteinuria in an animal model of glomerulosclerosis, and conferred superior renoprotection compared to enalapril.46

Strengths and Limitations

The strengths of our study include the use of the gold standard measure of UAE and utilizing longitudinal data based on repeated measurements of BP performed over long time periods. Additionally, we conducted the study in clinically healthy, community-dwelling individuals who were not using antihypertensive medications to minimize the confounding effects of comorbidities and antihypertensive medications. Moreover, the statistical methods used in the present study26–28 allowed us to avoid methodological limitations that can complicate the comparisons of the inter-related indices of BP, such as multicollinearity or the well-known concerns with the sole use of stepwise logistic regression analysis.47

One factor that potentially limits the generalizability of our results is that the BLSA participants are predominantly White, well-educated and health-conscious individuals. Another important limitation of our study is that UAE was measured at a single time point. Therefore, the effect of BP on longitudinal changes in UAE cannot be deciphered from the present study. Additionally, because of the phenomenon of PP amplification across the arterial tree, the operational BP at the level of the kidneys may differ from brachial BP and may be closer to central BP. However, longitudinal measurements of central arterial BP were not available in this cohort. Finally, the longitudinal index for each variable was computed by dividing the cumulative exposure to that variable by the number of follow-up years for each subject. This approach, which was necessary to ensure the comparability of longitudinal indices among subjects with differing durations of follow-up, may dilute the effect of the duration of exposure to each variable. However, this would not be expected to affect our findings because the duration of exposure to each of the 4 indices of BP was similar within each subject (i.e., equal to the duration of follow-up).

Conclusions

This longitudinal study provides robust evidence that the pulsatile component of BP confers the highest risk for BP-induced renal microvascular injury, as evidenced by UAE. Although our findings were restricted to men, our results do not rule out the possibility of similar associations in women with a higher vascular risk burden or a longer duration of exposure to elevated PP. Future studies should examine whether PP reduction with interventions that reduce central arterial stiffness48 can enhance the renoprotective benefits of BP reduction beyond that conferred by achieving conventional BP goals alone.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute on Aging, a portion of which was through a Research and Development Contract with MedStar Research Institute.

Footnotes

Disclosures

None

References

- 1.Sarnak MJ, Levey AS, Schoolwerth AC, Coresh J, Culleton B, Hamm LL, McCullough PA, Kasiske BL, Kelepouris E, Klag MJ, Parfrey P, Pfeffer M, Raij L, Spinosa DJ, Wilson PW. Kidney disease as a risk factor for development of cardiovascular disease: a statement from the American Heart Association Councils on Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease, High Blood Pressure Research, Clinical Cardiology, and Epidemiology and Prevention. Circulation. 2003;108(17):2154–2169. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000095676.90936.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Danziger J. Importance of low-grade albuminuria. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 2008;83(7):806–812. doi: 10.4065/83.7.806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deckert T, Feldt-Rasmussen B, Borch-Johnsen K, Jensen T, Kofoed-Enevoldsen A. Albuminuria reflects widespread vascular damage. The Steno hypothesis. Diabetologia. 1989;32(4):219–226. doi: 10.1007/BF00285287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lindeman RD, Tobin JD, Shock NW. Association between blood pressure and the rate of decline in renal function with age. Kidney Int. 1984;26(6):861–868. doi: 10.1038/ki.1984.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parving HH, Mogensen CE, Jensen HA, Evrin PE. Increased urinary albumin-excretion rate in benign essential hypertension. Lancet. 1974;1(7868):1190–1192. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(74)91002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wiseman M, Viberti G, Mackintosh D, Jarrett RJ, Keen H. Glycaemia, arterial pressure and micro-albuminuria in type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 1984;26(6):401–405. doi: 10.1007/BF00262209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Redon J, Liao Y, Lozano JV, Miralles A, Baldo E, Cooper RS. Factors related to the presence of microalbuminuria in essential hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 1994;7(9 Pt 1):801–807. doi: 10.1093/ajh/7.9.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pascual JM, Rodilla E, Miralles A, Gonzalez C, Redon J. Determinants of urinary albumin excretion reduction in essential hypertension: A long-term follow-up study. Journal of hypertension. 2006;24(11):2277–2284. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000249707.36393.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pedrinelli R, Dell'Omo G, Penno G, Bandinelli S, Bertini A, Di Bello V, Mariani M. Microalbuminuria and pulse pressure in hypertensive and atherosclerotic men. Hypertension. 2000;35(1 Pt 1):48–54. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.35.1.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cirillo M, Stellato D, Laurenzi M, Panarelli W, Zanchetti A, De Santo NG. Pulse pressure and isolated systolic hypertension: association with microalbuminuria. The GUBBIO Study Collaborative Research Group. Kidney Int. 2000;58(3):1211–1218. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Redon J, Rovira E, Miralles A, Julve R, Pascual JM. Factors related to the occurrence of microalbuminuria during antihypertensive treatment in essential hypertension. Hypertension. 2002;39(3):794–798. doi: 10.1161/hy0302.105209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Verhave JC, Fesler P, du Cailar G, Ribstein J, Safar ME, Mimran A. Elevated pulse pressure is associated with low renal function in elderly patients with isolated systolic hypertension. Hypertension. 2005;45(4):586–591. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000158843.60830.cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palatini P, Mormino P, Dorigatti F, Santonastaso M, Mos L, De Toni R, Winnicki M, Dal Follo M, Biasion T, Garavelli G, Pessina AC. Glomerular hyperfiltration predicts the development of microalbuminuria in stage 1 hypertension: the HARVEST. Kidney Int. 2006;70(3):578–584. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5001603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsakiris A, Doumas M, Lagatouras D, Vyssoulis G, Karpanou E, Nearchou N, Kouremenou C, Skoufas P. Microalbuminuria is determined by systolic and pulse pressure over a 12-year period and related to peripheral artery disease in normotensive and hypertensive subjects: the Three Areas Study in Greece (TAS-GR) Angiology. 2006;57(3):313–320. doi: 10.1177/000331970605700307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parving HH, Lewis JB, Ravid M, Remuzzi G, Hunsicker LG. Prevalence and risk factors for microalbuminuria in a referred cohort of type II diabetic patients: a global perspective. Kidney Int. 2006;69(11):2057–2063. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Viazzi F, Leoncini G, Ratto E, Vaccaro V, Tomolillo C, Falqui V, Parodi A, Conti N, Deferrari G, Pontremoli R. Microalbuminuria, blood pressure load, and systemic vascular permeability in primary hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2006;19(11):1183–1189. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2006.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mitchell GF. Effects of central arterial aging on the structure and function of the peripheral vasculature: implications for end-organ damage. J Appl Physiol. 2008;105(5):1652–1660. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.90549.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O'Rourke MF, Safar ME. Relationship between aortic stiffening and microvascular disease in brain and kidney: cause and logic of therapy. Hypertension. 2005;46(1):200–204. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000168052.00426.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mimran A. Consequences of elevated pulse pressure on renal function. J Hypertens Suppl. 2006;24(3):S3–S7. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000229462.24857.b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loutzenhiser R, Bidani A, Chilton L. Renal myogenic response: kinetic attributes and physiological role. Circulation research. 2002;90(12):1316–1324. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000024262.11534.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shock NW, Greulich RC, Aremberg D, Costa PT, Lakatta EG, Tobin JD. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1984. Normal Human Aging: The Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. NIH Publication 84–2450. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hougaku H, Fleg JL, Najjar SS, Lakatta EG, Harman SM, Blackman MR, Metter EJ. Relationship between androgenic hormones and arterial stiffness, based on longitudinal hormone measurements. American journal of physiology. 2006;290(2):E234–E242. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00059.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39(2 Suppl 1):S1–S266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li S, Chen W, Srinivasan SR, Bond MG, Tang R, Urbina EM, Berenson GS. Childhood cardiovascular risk factors and carotid vascular changes in adulthood: the Bogalusa Heart Study. Jama. 2003;290(17):2271–2276. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.17.2271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Najjar SS, Scuteri A, Shetty V, Wright JG, Muller DC, Fleg JL, Spurgeon HP, Ferrucci L, Lakatta EG. Pulse wave velocity is an independent predictor of the longitudinal increase in systolic blood pressure and of incident hypertension in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2008;51(14):1377–1383. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.10.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davidson R, MacKinnon JG. Several Tests for Model Specification in the Presence of Alternative Hypotheses. Econometrica. 1981;49(3):781–793. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mizon GE, Richard J-F. The Encompassing Principle and its Application to Testing Non-Nested Hypotheses. Econometrica. 1986;54(3):657–678. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davidson R, MacKinnon JG. Improving the reliability of bootstrap tests with the fast double bootstrap. Computational Statistics & Data Analysis. 2007;51(7):3259–3281. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Young JH, Klag MJ, Muntner P, Whyte JL, Pahor M, Coresh J. Blood pressure and decline in kidney function: findings from the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP) J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13(11):2776–2782. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000031805.09178.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bakris GL, Weir MR, Shanifar S, Zhang Z, Douglas J, van Dijk DJ, Brenner BM. Effects of blood pressure level on progression of diabetic nephropathy: results from the RENAAL study. Archives of internal medicine. 2003;163(13):1555–1565. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.13.1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Applegate WB. Quality of life during antihypertensive treatment. Lessons from the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program. Am J Hypertens. 1998;11(3 Pt 2):57S–61S. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(98)00012-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Christensen KL. Reducing pulse pressure in hypertension may normalize small artery structure. Hypertension. 1991;18(6):722–727. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.18.6.722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.James MA, Watt PA, Potter JF, Thurston H, Swales JD. Pulse pressure and resistance artery structure in the elderly. Hypertension. 1995;26(2):301–306. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.26.2.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laurent S. Evidence for benefits of perindopril in hypertension and its complications. Am J Hypertens. 2005;18(9 Pt 2):155S–162S. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tuttle KR. Cardiovascular implications of albuminuria. Journal of clinical hypertension (Greenwich, Conn. 2004;6(11 Suppl 3):13–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-6175.2004.04234.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Knight SF, Quigley JE, Yuan J, Roy SS, Elmarakby A, Imig JD. Endothelial dysfunction and the development of renal injury in spontaneously hypertensive rats fed a high-fat diet. Hypertension. 2008;51(2):352–359. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.099499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ceravolo R, Maio R, Pujia A, Sciacqua A, Ventura G, Costa MC, Sesti G, Perticone F. Pulse pressure and endothelial dysfunction in never-treated hypertensive patients. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2003;41(10):1753–1758. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00295-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Iliescu R, Reckelhoff JF. Sex and the kidney. Hypertension. 2008;51(4):1000–1001. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.101345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cirillo M, Senigalliesi L, Laurenzi M, Alfieri R, Stamler J, Stamler R, Panarelli W, De Santo NG. Microalbuminuria in nondiabetic adults: relation of blood pressure, body mass index, plasma cholesterol levels, and smoking: The Gubbio Population Study. Archives of internal medicine. 1998;158(17):1933–1939. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.17.1933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Verhave JC, Hillege HL, Burgerhof JG, Navis G, de Zeeuw D, de Jong PE. Cardiovascular risk factors are differently associated with urinary albumin excretion in men and women. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14(5):1330–1335. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000060573.77611.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ritz E. Cardiovascular risk factors and urinary albumin: vive la petite difference. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14(5):1415–1416. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000065641.03340.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Neugarten J. Gender and the progression of renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13(11):2807–2809. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000035846.89753.d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wachtell K, Ibsen H, Olsen MH, Borch-Johnsen K, Lindholm LH, Mogensen CE, Dahlof B, Devereux RB, Beevers G, de Faire U, Fyhrquist F, Julius S, Kjeldsen SE, Kristianson K, Lederballe-Pedersen O, Nieminen MS, Okin PM, Omvik P, Oparil S, Wedel H, Snapinn SM, Aurup P. Albuminuria and cardiovascular risk in hypertensive patients with left ventricular hypertrophy: the LIFE study. Annals of internal medicine. 2003;139(11):901–906. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-11-200312020-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Coresh J, Selvin E, Stevens LA, Manzi J, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Levey AS. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the United States. Jama. 2007;298(17):2038–2047. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.17.2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mitchell GF, Izzo JL, Jr, Lacourciere Y, Ouellet JP, Neutel J, Qian C, Kerwin LJ, Block AJ, Pfeffer MA. Omapatrilat reduces pulse pressure and proximal aortic stiffness in patients with systolic hypertension: results of the conduit hemodynamics of omapatrilat international research study. Circulation. 2002;105(25):2955–2961. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000020500.77568.3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Taal MW, Nenov VD, Wong W, Satyal SR, Sakharova O, Choi JH, Troy JL, Brenner BM. Vasopeptidase inhibition affords greater renoprotection than angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition alone. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12(10):2051–2059. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V12102051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tabachnik BG, Fidell LS. Using Multivariate Statistics. Third ed. New York, NY: HarperCollins; 1996. Logistic Regression; pp. 575–634. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kass DA, Shapiro EP, Kawaguchi M, Capriotti AR, Scuteri A, deGroof RC, Lakatta EG. Improved arterial compliance by a novel advanced glycation end-product crosslink breaker. Circulation. 2001;104(13):1464–1470. doi: 10.1161/hc3801.097806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]