Abstract

Objectives

Health Canada's Program for Climate Change and Health Adaptation in Northern First Nation and Inuit Communities is unique among Canadian federal programs in that it enables community-based participatory research by northern communities.

Study design

The program was designed to build capacity by funding communities to conduct their own research in cooperation with Aboriginal associations, academics, and governments; that way, communities could develop health-related adaptation plans and communication materials that would help in adaptation decision-making at the community, regional, national and circumpolar levels with respect to human health and a changing environment.

Methods

Community visits and workshops were held to familiarize northerners with the impacts of climate change on their health, as well as methods to develop research proposals and budgets to meet program requirements.

Results

Since the launch of the Climate Change and Health Adaptation Program in 2008, Health Canada has funded 36 community projects across Canada's North that focus on relevant health issues caused by climate change. In addition, the program supported capacity-building workshops for northerners, as well as a Pan-Arctic Results Workshop to bring communities together to showcase the results of their research. Results include: numerous films and photo-voice products that engage youth and elders and are available on the web; community-based ice monitoring, surveillance and communication networks; and information products on land, water and ice safety, drinking water, food security and safety, and traditional medicine.

Conclusions

Through these efforts, communities have increased their knowledge and understanding of the health effects related to climate change and have begun to develop local adaptation strategies.

Keywords: community-based participatory research, climate change, health

Over the last decade, climate change researchers as well as communities have begun to better understand the impacts that climate change is having on human health in Canada. Climate is rapidly changing and this is particularly evident in Canada's North. Melting sea and lake ice, melting glaciers, thawing permafrost, greater storm surges, increasing erosion and landslides, more unpredictable weather, more freezing rain in winter, shorter winter conditions, more forest fires, and hotter summers are some of the events being observed across Canada's North. Northerners have reported that these environmental changes are affecting their livelihoods, their relationship with the land, their culture, and their well-being (1–3). The ability to travel on land and ice in order to find and hunt traditional foods, to access potable water and maintain healthy homes and communities is becoming more difficult. Climate change is a human health issue as well as an environmental one. The health implications resulting from a warmer and more unpredictable climate are not distributed evenly: current health status, age, genetics, gender, geography, and economics, are all key variables affecting the ability of individuals and communities to adapt and reduce the effects of climate change. The expected outcomes of a warmer planet are numerous and will have direct and indirect health implications particularly for northern communities.

To help address these issues, it is important to involve those communities that are being directly affected by climate change in monitoring, discussing, advocating and participating in the process of climate change adaptation. Health Canada, as a part of the Canadian Government's overall climate change strategy, has developed a Climate Change and Health Adaptation Program for Northern First Nation and Inuit Communities. The intention of this program is to fund community-based participatory research, where the research is led and carried out by community members who develop culturally appropriate and locally-based adaptation strategies to reduce the effects of climate change on their health. The work is carried out by communities who determine their own research priorities with the assistance of Aboriginal associations, academics, governments and agencies where needed. For this program the participatory research must include: a study of the impacts of climate change on health incorporating both traditional knowledge and science; locally-appropriate adaptation plans and tools; and communication of the results to the community firstly, and then regionally and more broadly as appropriate. The planned outcome is to develop relevant information and tools/materials to help in decision-making at the community, regional, national and international levels with respect to human health and a changing environment. This type of research is an important instrument for community action as well as evidence-based policy development.

Community-based participatory research by Indigenous peoples is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) (4) as: “a research process that endeavours to balance interests, benefits and responsibilities between Indigenous peoples and the research institutions concerned, through a commitment to equitable research partnership”. The term implies that the entire process, from planning to reporting, will be transparent and accessible to all parties involved. This process has also been referred to as collaborative research.

Aboriginal people in Canada are assuming a greater role in determining the kind of research that is done in their communities and participating in this research. Although Aboriginal people in Canada, specifically First Nations and Inuit, share some common cultural traits and values, they have many distinctive beliefs, laws, customs and traditions (5), and there is a wide range of differences in the capacity of First Nations and Inuit communities and organizations to understand and participate in research. However, it is important to note that “Indigenous theoretical frameworks, methods, and applications are necessarily wide-ranging, reflecting diversity, context, and traditions of Indigenous peoples in Canada. The fundamental commonality in Indigenous research approaches and methods is the need to reflect Indigenous relationships to the environment, the land and the ancestors” (6).

The Environmental Health Research Division of Health Canada, who is administering the Climate Change Program, has 3 strategic goals with respect to building Aboriginal community-based participatory research capacity. The first is to ensure inclusion and recognition of Aboriginal values and traditional knowledge. The second is to enhance capacity, facilitate and evaluate translation of Aboriginal environmental health knowledge into policy and practice, and the third is to encourage/support strategic and Aboriginal-driven development planning (7).

A one size fits all model does not work for community-based participatory research considering that many communities have varying capacities and face different challenges and circumstances. Some communities benefit from outside expertise to assist in developing priorities, methodology and implementation, while others do not need this assistance. What is important for community-based participatory research is that Aboriginal knowledge is used in partnership with science-based knowledge. The combination is often much more powerful than either when used by itself. It is not easy, however, to integrate both types of knowledge and more work is required in this field (8,9).

This partnership of knowledge can be illustrated in one of the projects: “Traditional Knowledge: A Blueprint for Change” (10). The overall goal of the project was to train Inuit residents of North West River, Labrador to collect and map ecological knowledge of Inuit in the community and record their observations of on-going landscape transformations. Using this traditional knowledge of the land and its changes, the research team created a GIS database to store and input the information so that the community can use and update the information over time. The community has a robust baseline – including current and past characteristics – against which they can measure changing characteristics and future conditions. This project used western framework to store and house vital community traditional knowledge.

Community-based participatory research requires support not only from individual community members and researchers but also from community leadership and Aboriginal organizations. Strong partnerships with these participants can ensure that the research objectives are relevant, methodology is appropriate, communications are effective and that the research project is successful for all parties involved.

Material and methods

One of the goals of the program is to support research projects that include one of the following objectives: identify health risks including those affecting vulnerable peoples, analyse the risks to health, and/or conduct a health risk assessment, and examine exposure and/or modelling data collection. Proposals must also incorporate local/traditional knowledge and must include the development of adaptation approaches to climate change impacts, as well as a plan for communicating results back to the community or communities involved.

In order to ensure successful implementation of the program, a series of community visits, 15 in total, as well as 3 capacity-building workshops were held for communities and organizations to become familiar with climate change impacts, their potential effects on health, as well as methods to develop good research proposals and budgets that would meet the requirements of the funding agreements. These workshops were delivered in partnership with Aboriginal organizations and were held in Whitehorse, Yukon; Yellowknife, Northwest Territories; and Ottawa, Ontario. During the workshops, participants were invited to share their perceptions on what kind of changes they were experiencing and their concerns about these observed changes. It was then jointly determined which of the changes they mentioned were linked to climate effects and in turn how these could affect the health and well-being of affected communities. As participants became more familiar with climate change and health, they were invited to think about what kinds of projects they could undertake to reduce these effects. On the second day of the workshops, the participants, either in small groups or together, designed one or several research projects and developed a budget that had relevance to their own communities. Over the last 3 years, 50% of the proposals came as a direct result of visits and workshops (9 proposals from communities visited and 10 from the capacity-building workshops).

Also, to ensure all eligible communities were aware of the program and because not all communities could attend the capacity-building workshops, posters about the program and the application process were widely distributed. Plain-language application guides were developed that included step-by step procedures to develop a proposal to meet Health Canada's requirements. These guides were mailed to interested applicants and organizations and were made available on northern and Aboriginal websites. The application guides included the following topics: description of the climate change program and program goals, potential fields of study, funding amounts and deadline for submission, eligible candidates/communities, required elements of the proposals, collection and storage of data, proposal review and selection process, timelines and contact information, elements for Health Canada's Ethics Review Board approval process, a summary check list, and a CD with further information and templates (e.g. proposal, budget, consent forms) that could be used for developing the proposals. Required elements of the proposals included a cover page, plain language summary, community background, introduction, project description (background, objectives, rationale, methodology, activities/outcomes, partners, capacity building, and traditional knowledge), work plan and timelines, budget, project evaluation, communication and/or results, reporting plan, background information on team members, consent forms etc., and letter(s) of support by a mandated authority. Communities were encouraged to submit draft research proposals before the deadline for feedback. Several communities sent their proposals to the program for a pre-review. This pre-review helped to ensure that the applications met program criteria, and that proposals had clear objectives, goals and realistic timelines. These proposals were successful and received approvals from the selection committees.

This application procedure follows the World Health Organization recommendations (4) to ensure strong community-based participatory research.

In order to have an equitable and transparent review process for proposals, 2 selection committees were set up, one for First Nations and a second for Inuit. Members of the committees include climate change and health experts, northern experts, members of Aboriginal organizations and government staff who were responsible for approving budgets and implementing other aspects of the program. Committee members reviewed proposals and make final decisions on which communities/organizations would receive funding.

Results

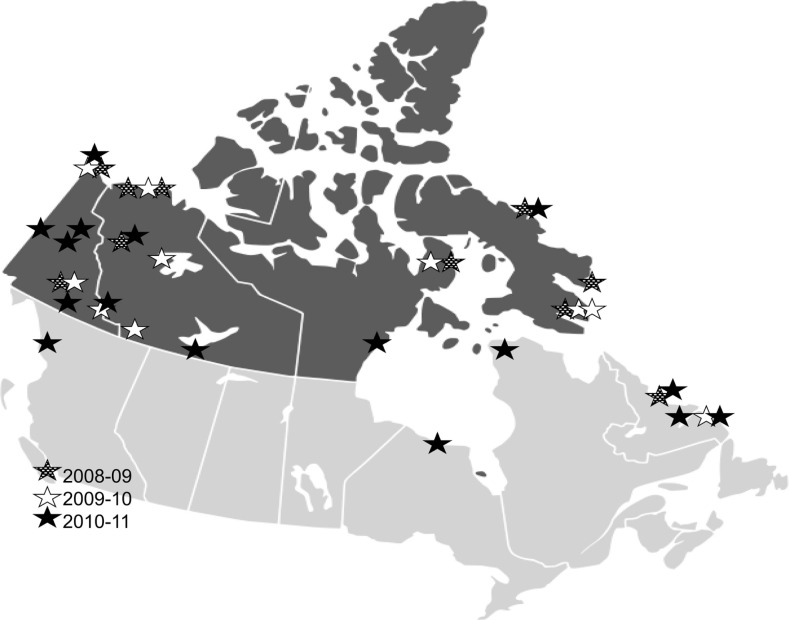

The workshops, community visits and other outreach activities generated considerable interest in the program. Ten community-based participatory health research projects from across Canada's North were funded in 2008–2009, 10 projects in 2009–2010 and 16 projects in 2010–2011 for a total of 36 (Fig. 1). Funding ranged from $30,000 to a maximum of $200,000 per year. Each year the requests for funding increased and were always greater than the funding available.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of Health Canada's Climate Change and Health Adaptation Programs funded from 2008–2011.

The research examined a range of topics including loss of traditional foods; water quality and safety, erosion/loss of permafrost, changes in traditional medicines; relationship with ice through ice monitoring; landslides; and numerous climate change and health research and education projects. Number and types of projects are listed in Table I.

Table I.

Areas of research for the Climate Change and Health Adaptation Program for Northern First Nations and Inuit Communities

| Area of research | Number of projects | Tools developed |

|---|---|---|

| Food security | 11 |

|

| Water quality | 2 |

|

| Education/Awareness/Promotion | 13 |

|

| Traditional medicine | 4 |

|

| Land erosion and land use | 2 |

|

| Ice monitoring | 3 |

|

| Water safety | 1 |

|

Many of the projects enabled youth to re-connect with their Elders and gain climate change and health awareness. In some cases, youth spent time in traditional wilderness camps learning about how to observe the land and its changes, about how to hunt and respect the land and wildlife, which helped to develop valuable attributes such as patience, respect, self-sufficiency, self-esteem and traditional knowledge on how their natural world is changing. Most importantly, youth gained a strong sense of purpose because they were a part, and in many cases, leading valuable climate change research projects. Youth created videos and blogs about their experiences and their observations of how climate change is affecting their health. These research videos are being used as education tools for youth in other regions across the North. As one of the 2008–2009 youth-driven projects points out (11), this type of research “created community conversations, discussions and awareness about climate change and its impact on health, and created many linkages between the often talked about belief that the ‘health of the land is the health of the people’ and the reality of climate change. In many ways, this project articulated the principle challenge of ‘research’, in that it remains largely a process and concept defined outside the community, and much of the challenge of community-based research is to create a way of coming- to- know that is respectful of and at the pace of the people involved.” As a number of the participants noted, these types of projects are creating strong voices that promote important messages about climate change and health not only for individual communities, but at a larger national and circumpolar level.

Some of the community-based research projects have been showcased internationally at events such as the 16th annual meeting of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP 16) held 29 November to 10 December 2010 in Mexico where nations met to assess progress in dealing with climate change and to negotiate climate change mitigation and adaptation measures. Two of the youth-led projects were invited to present their work at COP17 held 28 November to 9 December 2011 in South Africa. One of the films produced is the first-ever film about climate change impacts solely in Inuktitut (12).

In February 2011, a Pan-Arctic Results Workshop was held in Ottawa to bring northern communities, who received funding under the program, to showcase their research and results through photo-voice, videos, PowerPoint presentations, posters, and discussions. It was an opportunity for community researchers to meet others, share their project results and gain insight into what others are doing across the North. Over 150 attendees, mostly northerners but also government and non-government representatives, scientists, policy-makers, Members of Parliament, Aboriginal leaders and a few international experts actively participated in the workshop. There were some participants that had never left their communities but travelled to Ottawa to share the results of their work. Their participation is a testament to the importance that communities hold for their concern about effects of climate change for their own research and for sharing information with others in the hopes of creating further awareness and policy change.

During the workshop, participants were invited to fill in evaluation forms in order for the program to gain further perspective on how to meet the needs of community-based research and whether or not this style of workshop was beneficial for the dissemination of information. The evaluation form asked questions including: what did you like about workshop, what would have made it better, what was learned, what would you like to see as next steps for the program? With a response rate of 70%, the program received many compliments. A typical response is the following: “The program has accommodated communities at a variety of stages in understanding climate change and health issues and research. However, there remains a lot of work to be done in developing Indigenous research methodologies. This workshop represented a very useful “state of knowledge.” Many of the participants stated how important it was to have a space provided where communities can share their knowledge, their research, and their plans of how to deal with the changes through adaptation plans.” Participants also mentioned that the workshop was an opportunity to connect with and receive support from other researchers across the North where distances between communities are great and the isolation from research support is a challenge. Participants also stated that the workshop provided a forum for them to witness how their work was feeding into the “larger picture” of northern community research. One of the participant's responses when asked “What did you learn at this workshop?” summed up the effect of the workshop by saying: “I can make a difference.”

The results from all the research projects demonstrated the strong voices that represented community-based participatory research in Canada's North… voices that are creating impetus to deal with the many changes that they are experiencing.

Over the coming years, the results of this program will be used to develop innovative human health risk management plans and tools, including culturally-sensitive educational and awareness materials, to improve decision-making regarding local response plans/health adaptation measures and to raise awareness of potential vulnerabilities at community, regional, national and international levels.

An interim evaluation of the Climate Change Program was conducted a year and a half after its inception on relevance, design and delivery, success, and immediate outcomes. The initial evidence showed that the program has been successful in all aspects including its 3 intended outcomes, namely: increasing access to climate change tools and information; building capacity; and promoting collaboration. Longer-term outcomes, namely increased use of adaptation information and products; increased capacity of communities to adapt to climate change and finally reduced vulnerabilities and risks to communities will be assessed in a subsequent evaluation.

Discussion

Integral to the program's success has been the level of community engagement throughout the years of program implementation. Communities played an active role in developing and managing research projects that were meaningful and beneficial to their communities. They determined their research needs and carried out the projects with the assistance of experts where and when they determined their need. The success of this program has been reported not only by individual communities who have benefitted from the program but also by First Nations and Inuit organizations and selection committee members.

During the capacity-building workshops, northern organizations and communities gained a clear understanding of the program's purpose, goals, scope, and an awareness of climate change and health links. Participation in the workshops was also an opportunity for government staff to listen to and gain a greater understanding of the many climate change and related challenges that northern communities are currently facing on a day-to-day basis. Following the workshops, program staff have given numerous presentations to government policy and program staff on these understandings and challenges.

Another successful aspect of the program was to have northerners participate in the selection committees to determine who would receive funding. Their experience and understanding of northern issues and challenges provided significant input to the selection committees during their deliberations. They also played a vital role in making suggestions on how to improve the program, its communication tools and the application guides by suggesting tools to include such as proposal and reporting templates. These changes will be implemented in the next versions of the applications guides.

One challenge with implementation was the location of the program, which is based in the south, in Ottawa. Distance from the North made building relationships more difficult when trying to support northern communities in their research. The program has been able to alleviate this challenge by visiting a number of the communities where staff presented information about the program and learned about local challenges. The program, however, has only been able to visit a portion of eligible communities. To illustrate, after the first call for proposals in 2009, program staff focussed on visiting the Yukon where the participation rate was the lowest. Staff worked with the Council of Yukon First Nations and met with chiefs and councils, health directors, and lands and resource directors in 8 communities to discuss the program and how communities could apply for funding. The following year, Yukon had the highest number of community participants and diversity in research topics.

When a community receives approval and funding, it is essential that the program works directly with the communities. This relationship ensures that there is a person available to support each community through the various research stages including interim reporting, research ethics board reviews, budget reporting, evaluations, and final reporting. It is imperative to build these relationships, to make connections, to be flexible in order to ensure that each community feels comfortable and that research projects are successful and beneficial to the community. This relationship also ensures achievement of 2 other essential steps of community-based participatory research as outlined by the WHO (4), namely:

Mechanisms ensure regular and effective liaison and communication between the community and research organization.

Course of action to be followed by both parties if the research is stopped due to an unforeseen inability to reach its objectives, or as a result of a collective decision by the community that they no longer wish to or can participate.

A significant challenge in this community-based participatory research is the duration of funding. To date the program has been limited to funding of 1 year at a time. Although applications are reviewed and approved 3 months before the beginning of the year, there are always delays in release of funds to communities who cannot start the research project without the funding, and should not commence research until all approvals and funding are in place. When the delays extend into the field season, important information cannot be collected and the quality of research is compromised. This delay has been noted by most if not all communities and the program is looking at different funding models, such as multi-year funding, to try and address the issues.

Another challenge is the requirements for ethics review, which for the most part require the same standards as western-based laboratory or medical research and do not consider the unique nature of community-based participatory research and the incorporation of traditional knowledge, which must be protected. These challenges are being worked on to ensure the ethics review can accommodate the unique nature of this research.

Although this model of community-based participatory research has been developed in consultation with northern communities and to fit Health Canada's requirements for approvals and funding, other comparable models have been developed such as the Community Adaptation and Vulnerability in Arctic Regions (CAVIAR) methodology (13). The CAVIAR group got its beginnings, during the 2007–2008 International Polar Year (IPY), with partners from Arctic countries who came together to respond to the need for systematic assessment of community vulnerabilities and adaptations across the Arctic. This methodology has been applied in 7 Arctic countries including Russia, Norway, Sweden, Finland, Greenland, Canada and Alaska who have used this framework and its multi-disciplinary methodology to describe their communities’ social and environmental conditions that have created exposure sensitivities and that require adaptation measures. This methodology does not limit itself to climate change and health but is an excellent approach to provide a framework for communities to be an active leader in determining their specific vulnerabilities and solutions.

Although community-based participatory research may be considered as grassroots-based, it is important to promote this research to empower communities to understand and be able to make decisions on the environmental changes that affect their health and livelihood. It is also important for the program to inform governments and other organizations on its achievements to support ground-up and top-down practices required to create the evidence and impetus that are needed to address the numerous climate change and health issues that northerners face including input that will contribute to understanding and awareness in the circumpolar world.

Acknowledgements

Authors wish to acknowledge the support of many Aboriginal and northern organizations that have assisted in numerous aspects of the implementation of this community-based research program, specifically the Assembly of First Nations, Council of Yukon First Nations, Dene Nation, Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, Pauktuutit Inuit Women of Canada, Gwich'in Council International, Inuit Research Advisors, Institute for Circumpolar Health, Canadian Society of Circumpolar Health, Arctic Health Research Network Yukon, Qaujigiartiit Health Research Centre (AHRN-NU) Nunavut, Makivik Corporation, Nunatsiavut Government – Health and Wellness, Nunavut Research Institute, and the Climate Change Program in Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada.

Conflict of interest and funding

The authors have not received any funding or benefits from industry or elsewhere to conduct this study.

References

- 1.Nickels S, Furgal C, Buell M, Moquin H. Unikkaaqatigiit – Putting the human face on climate change: perspectives from Inuit in Canada. Ottawa: Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, Nasivvik Centre for Inuit Health and Changing Environments at Laval University, Ajunnginiq Centre at the National Aboriginal Health Organization; 2006. p. 196. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Furgal C. Health impacts of climate change in Canada’s North. In: Séguin J, editor. Human health in a changing climate, a Canadian assessment of vulnerabilities and adaptive capacity. Ottawa: Health Canada; 2008. pp. 303–66. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centre for Indigenous Environmental Resources. How climate change uniquely impacts the physical, social and cultural aspects of first nations. Ottawa: Centre for Indigenous Environmental Resources, prepared for the Assembly of First Nations; 2006. [cited 2011 July 7]: [p. 57]. Available from: http://www.afn.ca/uploads/files/env/report_2_cc_uniquely_impacts_physical_social_and_cultural_aspects_final_001.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization (WHO) Centre for Indigenous Peoples’ Nutrition and Environment (CINE); Indigenous peoples and participatory health research: planning and management, preparing research agreements; Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. p. 21. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Obomsawin R. First nations and Inuit health branch. Ottawa: Health Canada; 2007. Cultural competency syllabus; p. 71. [Google Scholar]

- 6.McGregor D, Bayha W, Simmons D. “Our responsibility to keep the land alive”: voices of Northern indigenous researchers. Pimatisiwin, Aboriginal and Indigenous-Community Health. 2010;8:101–23. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kwiatkowski RE. Chiang Mai: HIA 2008 Asia and Pacific Regional Health Impact Assessment Conference; 2008. Community capacity building in conducting health impact assessments. [cited 2011 July 7]. Available from: http://www.hia2008chiangmai.com/pdf/A3.1_fullpaper.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kwiatkowski RE. Indigenous community based participatory research and health impact assessment: a Canadian example. Environ Impact Assess. 2010;31:445–50. doi: 10.1016/j.eiar.2010.02.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kwiatkowski RE, Tikhonov C, McClymont Peace D, Bourassa C. Canadian indigenous engagement and capacity building in health impact assessment. IAPA. 2009;27:57–67. [Google Scholar]

- 10.North West River, Labrador. Community Report to Health Canada. North West River: North West River Community; 2011. p. 21. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fort Good Hope, NWT. Community Report to Health Canada. Fort Good Hope: Fort Good Hope Community; 2009. p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Isuma Productions. Montréal: Isuma Productions; 2010. Inuit knowledge and climate change. [cited 2011 July 20]. Available from: http://www.isuma.tv/inuit-knowledge-and-climate-change. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoversrud GK, Smit B, editors. Community adaptation and vulnerability in Arctic regions. International Polar Year (IPY) books. XVI. Dordrecht; New York: Springer; 2010. p. 353. [Google Scholar]