Abstract

Objective

To assess the efficacy of an intervention to encourage the adoption of smoke-free policies among owners and managers of multiunit housing.

Design

A pretest-posttest quasi-experimental design was employed.

Participants

The study population included 287 multiunit housing operators (MUHOs) from across New York State who were recruited to complete a baseline survey designed to assess policies about smoking in the housing units that they owned and/or managed. Subjects were surveyed between March and July 2008 (n = 128 intervention, n = 159 control) and recontacted 1 year later to complete a follow-up survey (n = 59 intervention, n = 95 control).

Intervention

An informational packet on the benefits of implementing a smoke-free policy was mailed to MUHOs in the New York State counties of Erie and Niagara between March and July 2008. For comparison purposes, a sample of MUHOs located outside of Erie and Niagara counties who did not receive the information packet were identified to serve as control subjects.

Main Outcome Measures

Logistic regression was used to assess predictors of policy interest, concern, and implementation at follow-up. Predictors included: intervention group, baseline status, respondent smoking status, survey type, government-subsidy status, quantity of units operated, and average building size, construction type, and age.

Results

Multiunit housing operators who received the information packet were more likely to report interest in adopting a smoke-free policy (OR = 6.49, 95% CI = 1.44–29.2), and less likely to report concerns about adopting such a policy (OR = 0.16, 95% CI = 0.04–0.66) compared to MUHOs who did not receive the information packet; however, the rate of adoption of smoke-free policies was comparable between the groups.

Conclusion

Sending MUHOs an information packet on the benefits of adopting a smoke-free policy was effective in addressing concerns and generating interest toward smoke-free policies but was not sufficient in itself to generate actual policy adoption.

Keywords: intervention studies, public policy, smoking, tobacco smoke pollution

There is a considerable body of scientific evidence documenting the detrimental effects of secondhand smoke (SHS), which has led to the adoption of policies to protect nonsmokers from exposure.1–4 As of April 2010, 38 states have instituted clean indoor air laws that prohibit smoking inside workplaces, bars, or restaurants, whereas 19 of these states have comprehensive laws in effect that prohibit smoking in all 3 venue types.5 These state laws, in addition to regional laws, cover approximately 74% of the US population.6 Studies of indoor air quality and biomarkers of exposure have found significant reductions in both indoor air pollution and salivary cotinine following the implementation of such laws.7–10 However, these policies are primarily targeted toward public areas, whereas limited effort has been devoted to personal living areas.

Personal living areas are major sources of SHS exposure for many individuals.2 Metabolites of a tobacco-specific lung carcinogen attributable to SHS have been observed in otherwise healthy, nonsmokers who have a spouse who smokes and exposure in the home has been consistently linked to an increased risk of heart disease and lung cancer in nonsmoking adults.2,11 Research suggests that smoke-free home policies reduce SHS in the home and can even increase cessation among smokers and decrease relapse among former smokers.12,13 Nonetheless, approximately 60% of smokers and 20% of nonsmokers report that smoking is permitted inside their home.14 This problem is compounded by the fact that Americans spend nearly 69% of their time in personal living spaces and the effects from SHS are intensified with increasing exposure.2,15,16

The potential for involuntary SHS exposure in the home is seemingly higher among individuals who reside in close proximity to one another in one of the approximately 22.5 million multiunit housing (MUH) structures throughout the United States17 Research indicates that SHS contains high levels of fine particulate matter that can infiltrate through building cracks and even brief exposure has been shown to adversely affect nonsmokers.18–22 Although many studies have assessed smoke-free policy support and adoption in public worksites,23,24 literature assessing these issues with respect to homes, and more specifically MUH, are limited. The few studies that have been conducted reveal that SHS transfer in MUH is common, that the prevalence of smoke-free policies is low, and that there is a lack of awareness of the benefits of such policies among multiunit housing operators (MUHOs).25–28

Accordingly, this study was undertaken to test the efficacy of a simple, low cost intervention aimed at encouraging MUHOs to adopt smoke-free policies.

Methods

Study population

Participants were identified using the Occupational Safety and Health Administration’s Standard Industrial Classification System. All individuals classified under Standard Industrial Classification code 65.13 (“operators of apartment buildings”) with New York State business addresses were eligible to participate. Eligible participants were stratified into 2 groups: (1) MUHOs located in Erie or Niagara counties (n = 241, intervention-eligible group); or (2) MUHOs located in New York State, but outside of Erie and Niagara counties (n = 4734, control-eligible group).

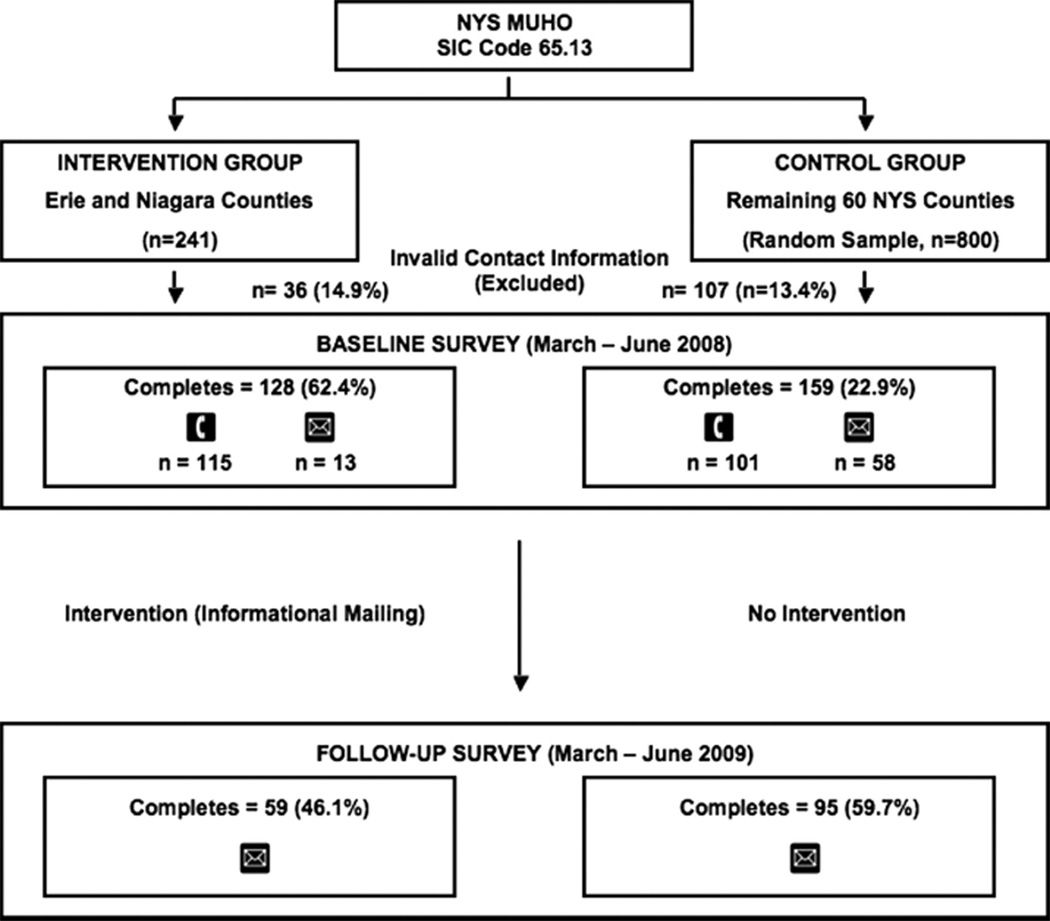

All MUHOs in the intervention-eligible group (n = 241) and a random sample of 800 MUHOs from the control-eligible group (16.9%) were invited to participate in the study. As shown in the Figure, 115 MUHOs in the intervention group and 101 MUHOs in the control group completed a baseline telephone survey between March and June 2008. Mail-based forms were subsequently sent to 533 subjects (n = 70 intervention, n = 463 control) who did not respond after 5 telephone call attempts. This secondary mailing resulted in 71 additional completed baseline surveys, of which 13 were from the intervention group and 58 were from the control group. In all, 287 MUHOs completed the baseline survey (n = 128 intervention, n = 159 control), which included 57 questions asking about the characteristics of the living units managed, existing smoking policies in those units, interest in and concerns about adopting a smoke-free policy, and demographic and smoking history information of the respondent. After correcting for invalid contact information, the overall response rate to the baseline survey was 32% (62.4% intervention, 22.9% control).

FIGURE. Flowchart of Participant Recruitment.

Abbreviations: MUHO, Multiunit housing operator; NYS, New York State; SIC, standard industrial classification.

Participants who completed the baseline survey were sent a follow-up survey between March and July 2009. The follow-up survey was administered by mail only with 2 mailing attempts. The overall response rate to the follow-up survey was 53.6% (46.1% intervention, 59.7% control).

Participants were compensated $50 for completing each survey. All procedures were reviewed and approved by the institutional review board at Roswell Park Cancer Institute.

Intervention

The intervention consisted of an information packet that included the following 3 components: (1) a report summarizing the findings of the baseline MUHO survey; (2) a fact sheet detailing answers to frequently asked questions regarding the legality and benefits of a smoke-free policy for MUH; and (3) a report on smoke-free MUH in UNITS magazine, a publication of the National Apartment Association.29–31 The information packet was prepared in collaboration with the Erie-Niagara Tobacco-Free Coalition and mailed to all individuals in the intervention group (n = 128) along with a cover letter from the Director of Erie-Niagara Tobacco-Free Coalition offering assistance in policy implementation.

Outcome Measures

Three primary outcomes measures were assessed to evaluate the benefits of the intervention. These included (1) presence or absence of a smoke-free policy; (2) interest in adopting a smoke-free policy; and (3) concerns expressed about a smoke-free policy. The measures used to assess each of these outcomes are described below:

Smoke-free policy

Respondents were asked: “Do you currently have a policy in place restricting smoking in any of the apartment units in your buildings?” Respondents, who indicated a response of “yes,” were subsequently asked: “Is smoking prohibited inside all the residential units within any of your buildings?” Respondents were considered to have a smoke-free policy if they answered “yes” to the first question and a smoke-free building policy if they also answered “yes” to the second question.

Interest in a smoke-free policy

Respondents who answered “no” to the question: “Do you currently have a policy in place restricting smoking in any of the apartment units in your buildings?” were asked: “How interested are you in restricting smoking in any of your units and/or buildings?” Respondents were asked to choose a single response from the following options: “very interested,” “somewhat interested,” “a little interested,” or “not at all interested.” Respondents were considered to be interested in implementing a smoke-free policy if they answered “very interested,” “somewhat interested,” or “a little interested” to the aforementioned question.

Concerns expressed about a smoke-free policy

Respondents who answered “no” to the question: “Do you currently have a policy in place restricting smoking in any of the apartment units in your buildings?” were asked: “What is the most important concern you have about restricting smoking in any of your units and/or buildings?” Respondents were asked to choose a single response from the following options: “higher vacancy rate,” “higher turnover,” “decrease in market size of potential tenants,” “increase in staff time for enforcement,” “legal costs associated with enforcement,” “legality of smoke-free designation,” “no concern,” or “other.” Respondents who indicated a response other than “no concern” were considered to have a concern about policy implementation.

Covariates

Respondents were asked to provide the following information about their MUH properties: quantity of units owned and/or managed (open response), quantity of units subsidized by the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) (open response), average building age (≤10, 11–20, 21–30, >30 years), average building size (2–4, 5–9, 10+ units, and ≤3 floors, 10+ units and 4+ floors), and building construction type (masonry, wood-frame, other). Respondents were also asked about their smoking status (smoker vs nonsmoker).

Data Analysis

The data presented in this article are limited to the 154 respondents who completed both the baseline and follow-up surveys. All data analyses were performed using SPSS 14.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, Illinois). Descriptive statistics from the baseline interview were used to compare the equivalence of the 2 study groups. Two-sample t tests and χ2 tests were used to identify statistically significant differences between the intervention and control groups, whereas a McNemar test was used to identify significant differences within groups.

Binary logistic regression models were constructed to test the impact of the intervention and to identify significant predictors of the following outcomes: (1) smoke-free policy or no policy; (2) interest in a smoke-free policy or no interest in a policy; and (3) concerns expressed about a smoke-free policy or no concerns expressed. Predictor variables included: intervention status (intervention or control), baseline status (interest/concern or no interest/no concern), baseline survey type (telephone or mail), respondent smoking status (nonsmoker or smoker), quantity of units owned/managed (2–49, 50–99, 100–149, or 150 or more units), HUD subsidy status (no HUD units or any HUD units), as well as average building age (≤20, 21–30, or >30 years), size (2–4, 5–9, or 10 or more units), and construction type (all masonry, all wood-frame, or other).

Results

Participant characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the baseline characteristics of the participants and shows that the intervention and control groups were largely equivalent with regard to demographics and smoking history. The only difference between intervention and control groups was building construction type, with a higher percentage of the intervention group reporting all masonry construction compared to controls.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Respondents in the Intervention and Control Groups

| Interventiona (n = 59) |

Controlb (n = 95) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | P (χ2) | |

| Total units owned/managed | .10 | ||||

| 2–49 | 19 | 32.2 | 38 | 40.0 | |

| 50–99 | 9 | 15.3 | 25 | 26.3 | |

| 100–149 | 15 | 25.4 | 13 | 13.7 | |

| ≥150 | 16 | 27.1 | 19 | 20.0 | |

| Average size of buildings | .68 | ||||

| 2–4 units | 16 | 27.1 | 27 | 28.4 | |

| 5–9 units | 13 | 22.0 | 26 | 27.4 | |

| ≥10 units | 30 | 50.9 | 42 | 44.2 | |

| Average age of buildings | .50 | ||||

| ≤20 y | 15 | 25.4 | 19 | 20.0 | |

| 21–30 y | 9 | 15.3 | 21 | 22.1 | |

| >30 y | 35 | 59.3 | 55 | 57.9 | |

| Construction type of buildings | <.01 | ||||

| All masonry | 37 | 62.7 | 30 | 31.6 | |

| All wood-frame | 15 | 25.4 | 50 | 52.6 | |

| Other | 7 | 11.9 | 15 | 15.8 | |

| HUDc subsidy status of units | .38 | ||||

| No HUD units | 28 | 47.5 | 52 | 45.3 | |

| HUD units | 31 | 52.5 | 43 | 52.5 | |

| Smoking status of respondent | .23 | ||||

| Nonsmoker | 52 | 88.1 | 89 | 93.7 | |

| Smoker | 7 | 11.9 | 6 | 6.3 | |

Intervention = Erie and Niagara counties, New York.

Control = New York State excluding Erie and Niagara counties.

US Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Smoke-free policy

Table 2 shows that 13.6% (21 of 154) of MUHOs reported that smoking was prohibited inside all the units within any of their buildings (ie, smoke-free building policy) at baseline compared to 18.8% (29 of 154) 1 year later. An additional 3.9% reported that smoking was prohibited inside individual units but not entire buildings at baseline, which remained unchanged at follow-up. Exposure to the intervention did not significantly increase the adoption of a smoke-free building policy. Between baseline and follow-up 6.8% (4 of 59) of MUHOs in the intervention condition reported implementing a smoke-free building policy compared to 6.3% (6 of 95) in the control group. Two MUHOs removed their smoke-free building policy between baseline and follow-up, one of which was from the control group. Adoption of a smoke-free building policy was also not found to be significantly associated with any of the measures of building characteristics or to respondent smoking status.

TABLE 2.

Type of Smoke-Free Policies Reported by Study Groupa

| Interventionb (n = 59) |

Controlc (n = 95) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Baseline, n (%) | Follow-up, n (%) | Relative % Difference |

Baseline, n (%) | Follow-up, n (%) | Relative % Difference |

| At least 1 smoke-free building | 6 (10.2) | 9 (15.3) | +33.3 | 15 (15.8) | 20 (21.1) | +25.1 |

| At least 1 smoke-free unitd | 7 (11.9) | 11 (18.6) | +36.0 | 20 (21.1) | 24 (25.3) | +16.6 |

There were no statistically significant differences observed between or within groups.

Intervention = Erie and Niagara counties, New York.

Control = New York State Excluding Erie and Niagara counties.

Includes MUHOs with a smoke-free building.

Interest in a smoke-free policy

A total of 77.3% (119 of 154) of MUHOs reported that they did not have any type of smoke-free policy at both baseline and follow-up (Table 3). Among these individuals, 72.3% (86 of 119) expressed interest in implementing a smoke-free policy at baseline, whereas 77.3% (92 of 119) expressed such an interest 1 year later. At follow-up, the percent of MUHOs with self-reported interest in a smoke-free policy was greater among the intervention group (77.1%–87.5%, n = 48, P = .07) than among the control group (69.0%–70.4%, n = 71, P = .62).

TABLE 3.

| Intervention,c (n = 48) |

Control,d (n = 71) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Baseline, n (%) | Follow-up, n (%) | Relative% Difference |

Baseline, n (%) | Follow-up, n (%) | Relative% Difference |

| Interest in adopting a smoke-free policy | 37 (77.1) | 42 (87.5)e | +11.9 | 49 (69.0) | 50 (70.4) | +2.0 |

| Concerns about adopting a smoke-free policy | 41 (85.4) | 30 (62.5)e,f | −26.8 | 54 (76.1) | 62 (87.3)f | +12.8 |

| Primary type of concern | ||||||

| Increased vacancy | 10 (20.8) | 8 (16.7) | −19.7 | 21 (29.6) | 23 (32.4) | +8.6 |

| Decreased market share | 13 (27.1) | 12 (25.0) | −7.8 | 11 (15.5) | 11 (15.5) | No Change |

| Other | 18 (37.5) | 10 (20.8)e,f | −44.5 | 22 (31.0) | 28 (39.4)f | +21.3 |

Among respondents with no policy at either baseline or follow-up (n = 119).

No statistically significant differences were observed between intervention and control groups at baseline.

Intervention = Erie and Niagara counties, New York State.

Control = New York State excluding Erie and Niagara counties.

P < 0.05 when compared to control group at follow-up (χ2).

P < 0.05 when compared to baseline (McNemar).

Table 4 summarizes the results of a logistic regression analysis to identify predictors of interest in adopting a smoke-free policy at follow-up. Significant predictors of interest in adopting a smoke-free policy included exposure to the intervention (OR = 6.49, 95% CI = 1.44–29.2), baseline interest in policy implementation (OR = 5.25, 95% CI = 1.45–19.0), and having HUD-subsidized units (OR = 5.86, 95% CI = 1.56–21.9) or buildings with wood frame construction (OR = 5.37, 95% CI = 1.09–26.4).

TABLE 4.

Predictors of Interest in Smoke-Free Policy Implementation Among Multiunit Housing Operators at Follow-up, Binary Logistic Regressiona

| Predictor | n | % | ORb | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total units owned/managed | ||||

| 2–49 | 38 | 73.7 | 1.00 | |

| 50–99 | 27 | 81.5 | 1.07 | 0.17–6.53 |

| 100–149 | 25 | 80.0 | 0.56 | 0.11–2.91 |

| ≥150 | 29 | 82.8 | 1.59 | 0.29–8.80 |

| Average building size | ||||

| 2–4 units | 28 | 75.0 | 1.00 | |

| 5–9 units | 30 | 80.0 | 1.40 | 0.24–8.03 |

| ≥10 units | 61 | 80.3 | 1.11 | 0.25–4.90 |

| Average building age | ||||

| ≤20 y | 27 | 88.9 | 1.00 | |

| 21–30 y | 22 | 86.4 | 0.59 | 0.06–5.86 |

| >30 y | 70 | 72.9 | 0.33 | 0.05–2.33 |

| Building construction | ||||

| All masonry | 51 | 72.5 | 1.00 | |

| All wood-frame | 50 | 88.0 | 5.37c | 1.09–26.4 |

| Other | 18 | 72.2 | 0.59 | 0.09–3.70 |

| HUD subsidy status | ||||

| No HUD units | 57 | 66.7 | 1.00 | |

| HUD units | 62 | 90.3 | 5.86c | 1.56–21.9 |

| Participant smoking status | ||||

| Nonsmoker | 107 | 81.3 | 1.00 | |

| Smoker | 12 | 58.3 | 0.24 | 0.04–1.33 |

| Baseline Survey Type | ||||

| Telephone | 87 | 80.5 | 1.00 | |

| 32 | 75.0 | 1.42 | 0.40–5.10 | |

| Baseline interest status | ||||

| No Interest | 31 | 54.8 | 1.00 | |

| Interest | 88 | 87.5 | 5.25c | 1.45–19.0 |

| Intervention status | ||||

| Control | 71 | 73.2 | 1.00 | |

| Intervention | 48 | 87.5 | 6.49c | 1.44–29.2 |

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; HUD, US Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Among respondents with no policy at either baseline or follow-up (n = 119).

Adjusted for all covariates listed in table.

Statistically significant ORs are given in bold.

Concerns expressed about a smoke-free policy

Table 3 summarizes the concerns expressed by MUHOs with no smoke-free policy at baseline or follow-up. The most common concerns expressed were those related to vacancy rates and limiting the pool of potential tenants to which units could be rented. It appears that the intervention had a positive impact on reducing concerns about adopting a smoke-free policy. Among respondents who reported no smoke-free policy at either baseline or follow-up, an overall decrease was observed in the proportion of intervention participants who reported having a concern about such a policy (85.4%–62.5%, n = 48, P < .01) between baseline and follow-up. The greatest reductions in concern were related to higher vacancy rates (20.8%–16.7%, P = 0.48) and “other” issues (37.5%–20.8%, P = .01). In contrast, overall concern increased among controls (76.1%–87.3%, n = 71, P = .01) between baseline and follow-up. The greatest increases in concern among controls were related to higher vacancy rates (29.6%–32.4%, P = .75) and “other” issues (31.0%–39.4%, P = .04).

The results of the logistic regression analysis show that among respondents with no smoke-free policy at either baseline or follow-up, MUHOs from the intervention group (OR = 0.16, 95% CI = 0.04–0.66) and those with no baseline concern about policy implementation (OR = 0.19, 95% CI = 0.05–0.82) were less likely to report having a concern about implementing a smoke-free policy at follow-up. In contrast, MUHOs who operate either 50 to 99 total units (OR = 5.91, 95% CI = 1.05–33.2) or 150 or more units (OR = 12.5, 95% CI = 1.77–88.0) were more likely to report having a concern about implementing a smoke-free policy (data not shown).

Discussion

This study shows that sending MUHOs an information packet on the benefits of adopting a smoke-free policy was effective in addressing concerns and generating interest in a smoke-free policy. However, it was not sufficient in itself to generate actual policy adoption. This finding may be a consequence of limited sample size, interventional simplicity, and/or the relatively short period between intervention and follow-up. Given that MUHOs who designate smoke-free buildings must generate new lease amendments and provide due notice to tenants, the time frame for implementation may have been too limited to see a change in actual policy adoption.32,33 Therefore, future studies should incorporate more time-intensive interventions with repeated messages and longer follow-up periods to more accurately gauge the impact of efforts to influence policy adoption.

The findings also reveal that smoke-free policies in MUH are presently more the exception than the rule, with fewer than 20% of MUHOs reporting a smoke-free policy. This figure is higher than previously conducted assessments, which may suggest an increasing trend toward the adoption of such policies with time.14 Our results also suggest that managers who operate units subsidized through HUD and those who manage wood-frame buildings expressed the greatest interest in adopting a smoke-free policy. Possible explanations for these findings include the disproportionately higher rates of smoking and MUH residency among individuals with low socioeconomic status27 and increased susceptibility to fire damage.

The US Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Promote Healthy Homes emphasizes the public health impact of housing and stresses the importance of instituting smoke-free policies in MUH.34 There are currently no federal or state laws that prevent MUHOs from implementing smoking restrictions.32 This legal permissibility extends to living units subsidized through HUD, which strongly encourages Public Housing Authorities to implement smoking restrictions in some or all of their units.35

There are several limitations to the current study that need to be acknowledged. First, participants were not randomly assigned to receive the intervention. There were differences in respondent characteristics by interventional group, not the least of which was the geographic distribution of respondents. More specifically, this geographic variation corresponds to relevant macro-economic factors that could influence the voluntary adoption of smoke-free policies. Both Erie and Niagara counties are relatively economically depressed regions that have lost substantial population over many years relative to the rest of New York State.36 Thus, the fact that there was an equivalent increase in the adoption of smoke-free policies in intervention and control areas may suggest that the intervention was more impactful than this study has described. Second, this study had a relatively modest sample size, so the power to detect a small but meaningful impact of the intervention was limited. Third, the study population was restricted to MUHOs in New York State, which limits the external validity of the findings. However, participants were recruited using a standardized system and random sampling was employed to identify controls. Moreover, estimates of policy interest and implementation were comparable to the only other published assessment of MUHOs.26

In summary, the present research indicates that an inexpensive, mail-based educational intervention appears to increase interest in smoke-free policies and decrease concerns about policy adoption among MUHOs. Because few MUHOs have designated smoke-free buildings, these findings provide evidence to support future efforts to develop interventions to promote policy adoption. Based on the concerns expressed by those without a smoke-free policy, economic incentives such as discounts on insurance and subsidies to promote advertising of smoke-free buildings are seemingly good strategies to accelerate smoke-free policy adoption among MUHOs.

Acknowledgments

This study was partially supported by a grant to the Erie-Niagara Tobacco-Free Coalition from the New York State Department of Health, Division of Chronic Disease, and Injury Prevention. Additional support was also provided by Grant/Cooperative Agreement Number 1R36 DP001848 from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

The authors thank Anthony Billoni and Annamaria Masucci from the Erie-Niagara Tobacco-Free Coalition for their logistical support.

REFERENCES

- 1.US Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Involuntary Smoking. A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health & Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, Center for Health Promotion, Office on Smoking & Health; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 2.US Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Involuntary Exposure to Tobacco Smoke: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Coordinating Center for Health Promotion, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.California Environmental Protection Agency. Identification of Environmental Tobacco Smoke as a Toxic Air Contaminant. San Francisco, CA: Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eriksen MP, Cerak RL. The diffusion and impact of clean indoor air laws. Annu Rev Public Health. 2008;29:171–185. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Americans for Non-Smokers’ Rights. [Accessed June 10, 2010];Smoke-Free Lists, Maps, and Data. http://www.no-smoke.org/goingsmokefree.php?id=519.

- 6.Americans for Non-Smokers’ Rights. [Accessed June 10, 2010];Percent of US State Population Protected by 100% Smoke-Free Air Laws. http://www.no-smoke.org/pdf/percentstatepops.pdf.

- 7.Travers MJ, Cummings KM, Hyland A, et al. Indoor air quality in hospitality venues before and after implementation of a clean indoor air law—Western New York, 2003. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53(44):1038–1041. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farrelly MC, Nonnemaker JM, Chou R, Hyland A, Peterson KK, Bauer UE. Changes in hospitality workers’ exposure to secondhand smoke following the implementation of New York’s smoke-free law. Tob Control. 2005;14:236–241. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.008839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abrams SM, Mahoney MC, Hyland A, Cummings KM, Davis W, Song L. Early evidence on the effectiveness of clean indoor air legislation in New York State. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(2):296–298. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.055012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bauer U, Juster H, Hyland A, et al. Reduced secondhand smoke exposure after implementation of a comprehensive statewide smoking ban — New York, June 26, 2003–June 30, 2004. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56(28):705–708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anderson KE, Carmella SG, Ye M, et al. Metabolites of a tobacco-specific lung carcinogen in nonsmoking women exposed to environmental tobacco smoke. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93(5):378–381. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.5.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hyland A, Higbee C, Travers MJ, et al. Smoke-free homes and smoking cessation and relapse in a longitudinal population of adults. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11(6):614–618. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mills A, Messer K, Gilpin E, Pierce J. The effect of smoke-free homes on adult smoking behavior: a review. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11(1):1131–1141. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giovino GA, Chaloupka FJ, Hartman AM, et al. Cigarette Smoking Prevalence and Policies in the 50 States: An Era of Change—The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation ImpacTeen Tobacco Chart Book. Buffalo, NY: University at Buffalo, SUNY; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klepeis NE, Nelson WC, Ott WR, et al. The National Human Activity Pattern Survey (NHAPS): a resource for assessing exposure to environmental pollutants. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol. 2001;11:231–252. doi: 10.1038/sj.jea.7500165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davis RM. Exposure to environmental tobacco smoke: identifying and protecting those at risk. JAMA. 1998;280:1947–1949. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.22.1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.US Census Bureau. American Housing Survey for the United States: 2007. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office; 2008. Current Housing Report, Series H150/07. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klepeis NE, Apte MG, Gundel LA, Sextro RG, Nazaroff WW. Determining size-specific emission factors for environmental tobacco smoke particles. Aerosol Sci Technol. 2003;37(10):780–790. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu DL, Nazaroff WW. Particle penetration through building cracks. Aerosol Sci Technol. 2003;37:565–573. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thatcher TL, Lunden MM, Revzan KL, Sextro RG, Brown NJ. A concentration rebound method for measuring particle penetration and deposition in the indoor environment. Aerosol Sci Technol. 2003;37:847–864. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Junker MH, Danuser B, Monn C, Koller T. Acute sensory response of nonsmokers at very low environmental tobacco smoke concentrations in controlled laboratory settings. Environ Health Perspect. 2001;109:1045–1052. doi: 10.1289/ehp.011091045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heiss C, Amabile N, Lee AC, et al. Brief secondhand smoke exposure depresses endothelial progenitor cells activity and endothelial function: sustained vascular injury and blunted nitric oxide production. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51(18):1760–1771. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Borland R, Yong HH, Siahpush M, et al. Support for and reported compliance with smoke-free restaurants and bars by smokers in four countries: findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Tob Control. 2006;15(suppl 3 iii):34–41. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.008748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hyland A, Higbee C, Borland R, et al. Attitudes and beliefs about secondhand smoke and smoke-free policies in four countries: findings from the International Tobacco Control Four Country Survey. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11(6):642–649. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hennrikus D, Pentel PR, Sandell SD. Preferences and practices among renters regarding smoking restrictions in apartment buildings. Tob Control. 2003;12:189–194. doi: 10.1136/tc.12.2.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hewett MJ, Sandell SD, Anderson J, Niebuhr M. Secondhand smoke in apartment buildings: renter and owner or manager perspectives. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9(suppl 1):S39–S47. doi: 10.1080/14622200601083442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.King BA, Travers MJ, Cummings KM, Mahoney MC, Hyland AJ. Prevalence and predictors of smoke-free policy implementation and support among owners and managers of multiunit housing. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12(2):159–163. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.King BA, Cummings KM, Mahoney MC, Juster HR, Hyland AJ. Multiunit housing residents’ experiences and attitudes toward smoke-free policies. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12(6):598–605. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.King BA, Hyland AJ, Billoni AG, Cummings KM. Western New York Landlords’ Preferences and Practices Regarding Smoke-Free Building Policies: Findings from Erie and Niagara Counties. Buffalo, NY: Roswell Park Cancer Institute; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 30.New York State Department of Health. [Acccesses February 18, 2011];Steps to Smoke-Free Housing N: Landlords and Property Owners’ Q & A. http://www.smokefreehousingny.org/landlords.html.

- 31.UNITS Magazine. Clearing the Air: Industry Discusses Trend Toward Smoke-Free Housing. Arlington, VA: National Apartment Association; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schoenmarklin S. Analysis of the Authority of Housing Authorities and Section 8 Multiunit Housing Owners to Adopt Smoke-Free Policies in Their Residential Units. [Accessed August 22, 2009];Smoke-Free Environments Law Project. http://www.tcsg.org/sfelp/public_housing24E577.pdf.

- 33.Carney D. [Accessed August 22, 2009];Legal Research Regarding Smoke-Free Buildings and Transfer of Environmental Tobacco Smoke Between Units in Smoking-Permitted Buildings. http://www.mncee.org/pdf/research/report.pdf.

- 34.US Department of Health and Human Services. The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Promote Healthy Homes. Rockville: US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 35.US Department of Housing and Urban Development. [Accessed August 7, 2010];Non-Smoking Policies in Public Housing. Notice: PIH-2009-21 (HA). http://www.hud.gov/offices/pih/publications/notices/09/pih2009-21.pdf. Published July 17, 2009.

- 36.New York State Comptrollers Office. [Accessed July 27, 2010];Population Trends in New York State’s Cities. http://www.osc.state.ny.us/localgov/pubs/research/pop_trends.pdf.