Abstract

Background

The purpose of this study was to elucidate the molecular basis of ocular albinism type I in a Chinese pedigree.

Methodology/Principal Findings

Complete ophthalmologic examinations were performed on 4 patients, 7 carriers and 17 unaffected individuals in this five-generation family. All coding exons of four-point-one (4.1), ezrin, radixin, moesin (FERM) domain-containing 7 (FRMD7) and G protein-coupled receptor 143 (GPR143) genes were amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), sequenced and compared with a reference database. Ocular albinism and nystagmus were found in all patients of this family. Macular hypoplasia was present in the patients including the proband. A novel nonsense hemizygous mutation c.807T>A in the GPR143 gene was identified in four patients and the heterozygous mutation was found in seven asymptomatic individuals. This mutation is a substitution of tyrosine for adenine which leads to a premature stop codon at position 269 (p.Y269X) of GPR143.

Conclusions/Significance

This is the first report that p.Y269X mutation of GPR143 gene is responsible for the pathogenesis of familial ocular albinism. These results expand the mutation spectrum of GPR143, and demonstrate the clinical characteristics of ocular albinism type I in Chinese population.

Introduction

Nystagmus is a common symptom of a range of diseases including at least three X-linked disorders, with one of those being ocular albinism type 1 (OA1; MIM 300500) mapped to Xp22.3 [1]. It should be distinguished from the congenital motor nystagmus (CMN), a hereditary disorder characterized by bilateral ocular oscillations that occurs in the absence of any obvious ocular disorders [2]. Identification of the underlying disease of CMN often requires extensive clinical, electrophysiological, psychophysical, and eventually molecular genetic examinations, especially when clinical findings are unrevealing [3], [4]. The prevalence of X-linked OA1 is estimated to be 1 in 50,000 live births. Most male patients with OA1 showed normal skin and hair pigment, but will usually have signs and symptoms of ocular albinism, including nystagmus, poor visual acuity, iris translucency, foveal hypoplasia and albinotic fundus [5], [6]. However, the characteristics of OA1 have not been well defined in Asians. OA1 is caused by mutations in the G protein-coupled receptor 143 (GPR143) gene, originally also known as the OA1 gene [7]. Various types of mutations in GPR143 have been identified in different countries, but X-linked OA1 in the Chinese population was rarely reported [8].

In the present study, a five-generation Chinese family with OA1was recruited. All affected individuals exhibited nystagmus as the main symptom and failed to show photophobia, iris translucency and strabismus. This pedigree was initially considered as congenital nystagmus. Diagnosis of OA1was made by extensive clinical examinations. Four-point-one (4.1), ezrin, radixin, moesin (FERM) domain-containing 7 (FRMD7 candidate gene for CMN) and G protein-coupled receptor 143 (GPR143, candidate gene for OA 1) genes were analyzed.

Methods

Family Recruitment

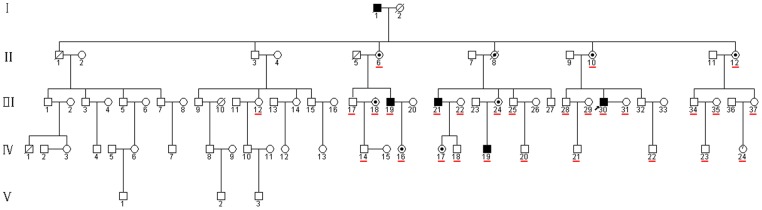

A five-generation Chinese family with OA1 was recruited in Sichuan (Figure 1). Written informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki before blood samples were taken for analysis (see attachment for details). Three minors were used in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the guardians on behalf of the minors (see attachment for details). This study was approved by both West China Hospital, Sichuan University Institute Review Board and North Sichuan Medical College Institute Review Board.

Figure 1. The pedigree of X-linked OA1.

A filled square indicates an affected male and a dot in the middle of the circle indicates a carrier. The proband is marked by an arrow. The underline indicates family members enrolled in this study.

Clinical Examination

Complete physical examination and detailed ophthalmological examination were carried out on the subjects of this family, including 4 affected patients, 7 carriers and some asymptomatic individuals. Visual acuity (VA) was measured using the best-corrected Snellen visual acuity test. Fundus and OCT examinations were performed using fundus camera (nonmyd WX 3D, Kowa, Japan) and Spectralis OCT (Heidelberg Engineering, Germay).

Mutation Screening and Sequence Analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from 200 µl of peripheral blood using the standard phenol/chloroform method. DNA integrity was evaluated by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis.

Mutation analysis of FRMD7 and GPR143 was performed using PCR and direct sequencing. Primers were designed to cover the sequences of all coding exons of the genes, according to published primer sequences with some modification (Table 1) [9], [10]. The primers were synthesized by Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). PCRs were carried out in a MyCycler thermocycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) using the following program: initial denaturation at 95°C for 2 min followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 10s, 54°C–56°C for 30s, and 72° for 1 min, and then a final extension at 72°C for 5 min.

Table 1. Primers used in PCR for amplification of FRMD7 and GPR143.

| Exon | Primer direction | Sequence (5′→3′) | Annealing temperature (°C) | Product size (bp) |

| 1 | FRMD7-1F | GAGAAAGCACCCACAGCACT | 56 | 229 |

| FRMD7-1R | CAGTCCTCCTTCATTCAGTCC | |||

| 2 | FRMD7-2F | TGTGGCTTCTACCCTTTATTC | 54 | 403 |

| FRMD7-2R | AGTGTTGGGATTACAGGCAT | |||

| 3 | FRMD7-3F | TGGAGCAGTGATTCAAATGTC | 54 | 336 |

| FRMD7-3R | TCTAACTGTGAACTCTCTTCCT | |||

| 4 | FRMD7-4F | CCTATAACTGTTGTGATGGAC | 54 | 260 |

| FRMD7-4R | CATCTCCCAGACAGTGACTTA | |||

| 5 | FRMD7-5F | TGCCAAAGTGTTCAATCAGC | 54 | 368 |

| FRMD7-5R | CTCCTGTGCTTGGTTCTCTA | |||

| 6+7 | FRMD7-6F | TGGAGGACAAGGGTATGCT | 55 | 642 |

| FRMD7-6R | GTGATAATACTGAGGGGTGAG | |||

| 8 | FRMD7-7F | GACCACAGCTCCTACCCAGT | 56 | 374 |

| FRMD7-7R | AAAGACACACCATCACTCAGG | |||

| 9 | FRMD7-8F | GAGCAATAGTTTGGAAGGCAT | 54 | 293 |

| FRMD7-8R | AAGAAGCAGTGTGAGCAGTTT | |||

| 10+11 | FRMD7-9F | TGTTCTCTGCCTGGTCCTTG | 55 | 532 |

| FRMD7-9R | TTTACACACTGGGATTCTGG | |||

| 12 | FRMD7-10F | CTACCCTAGAATAGAACATGGA | 54 | 702 |

| FRMD7-10R | ATTCCTTGGGCTTCTTTCAG | |||

| 12 | FRMD7-11F | GGAAAGGACAAGTCCACATA | 54 | 660 |

| FRMD7-11R | TTCTGCCTAAGTCGGTAACA | |||

| 1 | GPR-1F | AACCTTCCCAACCTTTCTGC | 55 | 698 |

| GPR-1R | CCTCTCGTCCTCACTCCATC | |||

| 2 | GPR-2F | CAGTGAGCAGGGTTTTTACCA | 55 | 537 |

| GPR-2R | AACAGACTCCCAGGGTTTGC | |||

| 3 | GPR-3F | GTCTACCCTGCCGTCTCAAG | 56 | 334 |

| GPR-3R | TGAGCTGCTGTGGATGTTTC | |||

| 4 | GPR-4F | CTCAGCAGCACGAGGAAACT | 56 | 465 |

| GPR-4R | ACAAACGAGAAAGGCAGAGC | |||

| 5 | GPR-5F | CTTAGGGGTCCTCCCATTTC | 55 | 575 |

| GPR-5R | TGGCACTGAGCTAACAAACG | |||

| 6 | GPR-6F | TCAGTGACTTGCTTTGCTTCCT | 54 | 387 |

| GPR-6R | TCCTCAAAGGGCACCTAGCA | |||

| 7 | GPR-7F | GCACCTGGCCCTCTTAGTTT | 55 | 458 |

| GPR-7R | ACCTGTAGTCCCAGTTACTCA | |||

| 8 | GPR-8F | ATGGTCCCTTCCAAGCGAGT | 56 | 494 |

| GPR-8R | GTTCACATGAGAGGTGCTGCT | |||

| 9 | GPR-9F | ACTCCATGCACTGAATACTGA | 54 | 485 |

| GPR-9R | GGATGTGGACCTTACACTTACT |

PCR products were directly sequenced using an ABI 377XL automated DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), and analyzed with the DNAStar (Madison, WI) software and compared with the published FRMD7 and GPR143 sequences. Mutation was named according to the nomenclature recommended by the Human Genomic Variation Society (HGVS).

Results

Clinical Phenotype

In this five-generation Chinese family, the disease was transmitted from female carrier to affected son, indicating that the disease was inherited in an X-linked recessive pattern (Figure 1). The clinical characteristics of OA1 in this pedigree are described as in Table 2, Figure 2 and 3.

Table 2. Summary of clinical features of affected males and female carriers.

| ID | Gender | Age | Visual acuity (left/right) | Iris hypopigmentation | Fundus hypopigmentation | Fundus foveal hypoplasia | Nystagmus | Mutation |

| patients | ||||||||

| III:19 | Male | 47 | 0.05/0.1 | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | hemizygous |

| III:21 | Male | 47 | 0.01/0.01 | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | hemizygous |

| III:30 | Male | 42 | 0.2/0.2 | Mild | No | Yes | Yes | hemizygous |

| IV:19 | Male | 21 | 0.1/0.1 | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | hemizygous |

| Carriers | ||||||||

| II6 | Female | 78 | 0.05/0.05 | No | Cataract, Unclear fundus | Cataract, Unclear fundus | No | heterozygous |

| II:10 | Female | 64 | 0.8/0.8 | No | No | No | No | heterozygous |

| II:12 | Female | 62 | 0.6/0.6 | No | No | No | No | heterozygous |

| III:18 | Female | 55 | 0.7/0.7 | No | No | No | No | heterozygous |

| III:24 | Female | 44 | 0.8/0.8 | No | No | No | No | heterozygous |

| IV:16 | Female | 20 | 1.0/1.0 (best corrected) | No | Yes (High myopia) | No | No | heterozygous |

| IV:17 | Female | 24 | 0.8/0.8 | No | No | No | No | heterozygous |

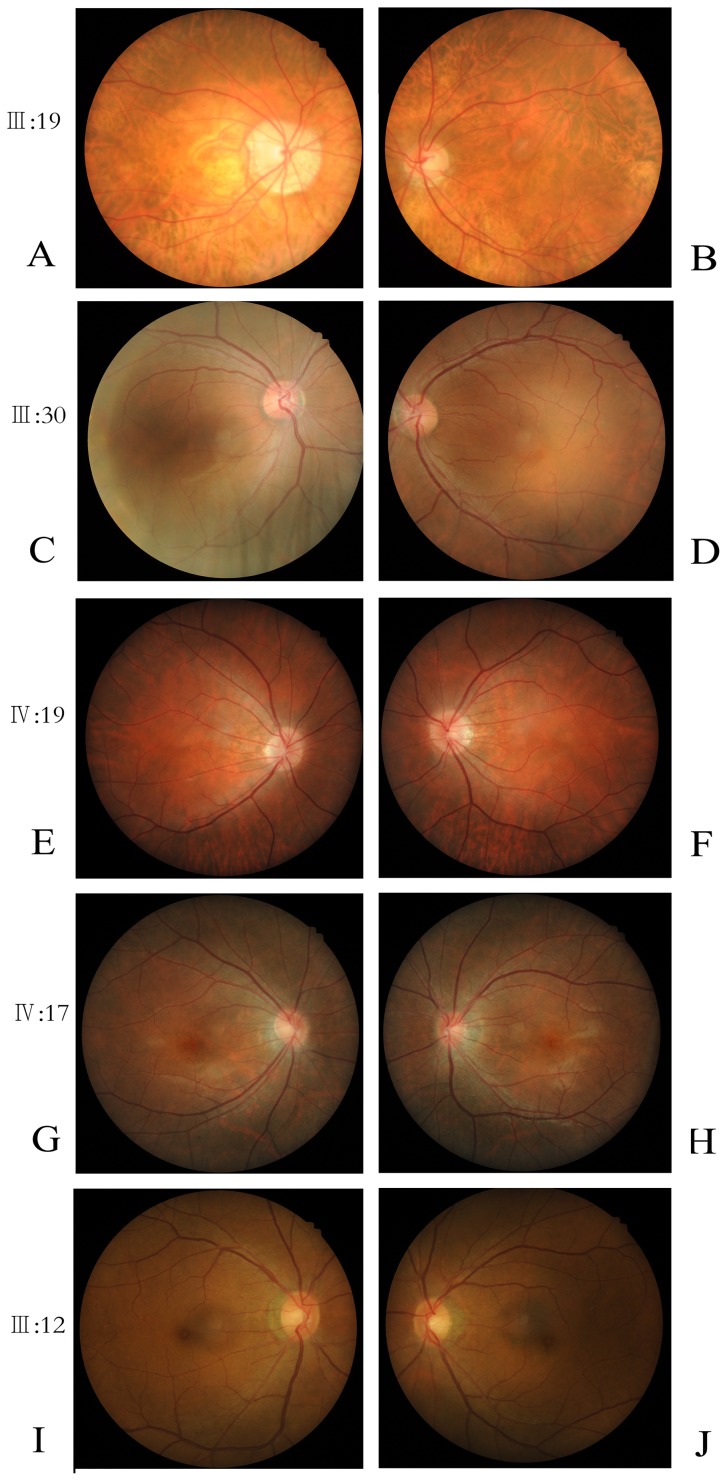

Figure 2. Fundus photographs of three patients, one carrier and one normal individual.

A–F: three patients; G–H: one carrier; I–J: one normal individual.

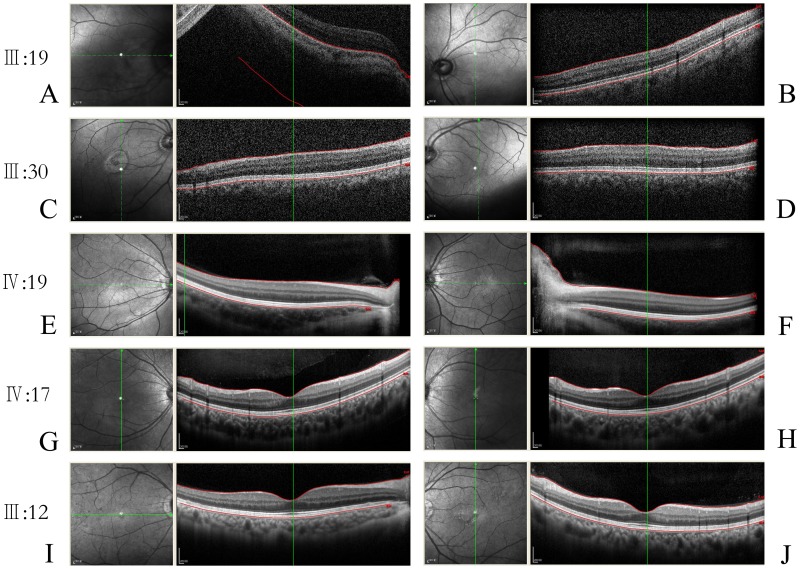

Figure 3. OCT test photographs of three patients, one carrier and one normal individual.

A–F: three patients; G–H: one carrier; I–J: one normal individual. It should be noted that detailed structural imaging of the fovea was not successfully obtained in two patients (III:19 and III:30) with more severe nystagmus due to their poor fixation. Foveal image of one patient (IV:19) with relatively mild nystagmus was obtained.

Reduced Visual Acuity and Nystagmus

All four patients presented with nystagmus and reduced visual acuity (corrected visual acuity of 0.01–0.2). The nystagmus was present during their first three months after birth. Eye movement recording revealed that the patients had conjugate horizontal nystagmus. The proband (patient III:30, Figure 1), a forty-two-year-old male, presented with nystagmus with best corrected visual acuity being 0.2 OD and 0.2 OS. He presented with nystagmus and congenital cataract on the fortieth day after birth and underwent cataract extraction and intraocular lens implantation at the age of 41. No pigmentation abnormality of skin and hair was observed in the participants. Ocular abnormalities were not found in other asymptomatic members examined in this family.

Presence of Hypopigmentation in the Fundus and Foveal Hypoplasia

Compared with normal individuals (Figure 2, I, J), the patients (III:19, IV:19) exhibited an albinotic fundus (Figure 2, A, B, C, D, E, F). All of the patients had foveal hypoplasia. The OCT showed extension of all neurosensory retinal layers through the area in which the fovea would normally be located (Figure 3). The clinical features of affected males and female carriers were shown in Table 2.

GPR143 Mutation Identification and Analysis

A novel nonsense mutation, c.807T>A, at codon 807 (TAT to TAA) of exon 7 in GPR143 gene was identified in all affected males. This mutation was presented as heterozygous in all obligate female carriers, and it was not found in normal members of the family. The c.807T>A mutation caused a substitution of tyrosine leading to a premature termination codon at position 269 (p.Y269X) of GPR143 protein.

Discussion

A Chinese family with “congenital” nystagmus as the main symptom was reported in this study. There is no difference in iris pigmentation between patients (except the proband) or carriers and normal individuals in this family. The patients presented with only mild hypopigmentation in fundus. The presence of foveal hypoplasia could be ignored since the macular morphology could not be easily obtained by OCT due to the poor fixation of the nystagmus eye of the patients. Therefore this Chinese family was considered originally as congenital nystagmus. Preising et al. reported that nystagmus, macular hypoplasia and hypopigmentation of the fundus were the characteristic signs of ocular albinism which are more reliable in identifying patients with albinism [6], [11].

For the molecular diagnosis of this pedigree, the FRMD7 gene (candidate gene for congenital nystagmus) and GPR143 gene (candidate gene for OA1) were analyzed. The sequence analysis of GPR143 demonstrated a novel nonsense mutation (p.Y269X) in exon 7. All affected males were hemizygous for the mutation and female carriers were heterozygous for the mutation whereas the other normal members of the family had no mutation. Another gene, FRMD7, involved in the development of congenital nystagmus, was screened and no mutation was found. Thus, the results of clinical and genetic findings provide solid evidence showing that this Chinese family has X-linked OA1, and the p.Y269X mutation of GPR143 is responsible for the pathogenesis.

Bassi et al. (1995) cloned GPR143 gene for ocular albinism type 1 from the distal short arm of the X chromosome [1]. Also in 1995, Schiaffino et al. screened GPR143 gene and detected various mutations in one-third of X-linked ocular albinism (XLOA) patients [7]. To date, about one hundred mutations of GPR143 were deposited in Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD), including deletion, frameshift, and nonsense mutations. Most of GPR143 mutations were reported in a large collection of patients mainly with ocular albinism [12], [13], [14], [15]. In 2001, Preising et al. reported an X-linked CN family with ocular albinism and found 14 bp deletion in GPR143 gene [6]. In 2007, Liu et al. identified a novel missense GPR143 mutation in a large Chinese family with CN as the most prominent and consistent manifestation [16]. In more recent years, GPR143 mutations have been identified in the other two Chinese families with X -linked CN without any classical phenotype of OA1. One family had a 37 bp deletion mutation in exon 1 of GPR143 [17]. The other family had a 19 bp duplication in exon 1 of GPR143 and all affected individuals exhibited nystagmus [10]. These two reports did not present sufficient clinical data to evaluate their hypothesis of isolated nystagmus from GPR143 variants. Preising et al. suggested male patients with congenital nystagmus were candidates for X-linked OA and a thorough clinical examination was needed [11]. Furthermore, analysis of the FRMD7 and GPR143 genes would be helpful to distinguish these two conditions from the molecular level.

GPR143 on chromosome Xp22.3 contains 9 exons and encodes a protein of 404 amino acids containing seven putative transmembrane domains and one potential N-glycosylation site using an asparagine at codon 106 [18]. GPR143 protein is a conserved integral membrane protein that has weak similarities to G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), which participate in the most common signal transduction system at the plasma membrane. It binds heterotrimeric G proteins, which suggests that GPR143 GPCR-mediated signal transduction systems also operate at the internal membranes in mammalian cells [19]. The p.Y269X mutation identified in our study was predicted to result in a truncated protein with 269 amino acids shorter than the normal full-length protein, suggesting that this is a loss-of-function mutation. Furthermore, the mutated transcript is likely to be degraded by the nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD) pathway. This hypothesis assumed that the truncated protein may not even be produced.

It is unclear how the mutated GPR143 causes the ocular abnormalities, such as macular hypoplasia in people with ocular albinism. Lopez et al. proposed that L-3, 4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (L-DOPA) might be a ligand for the protein encoded by GPR143 [20]. L-DOPA is a precursor in melanin synthesis that has been considered as an antimitogenic factor in cell cycle regulation, playing a crucial role in the maturation of the retina and the optic nerve [21], [22]. GPR143 is not involved in the production of melanin itself, but rather the pigment distribution or production of a precursor like L-DOPA as a cause of developmental anomalies of macular development. The impaired macular development might then cause the vision loss and nystagmus [11], as reported in this study.

The ocular disorders should be eliminated before the diagnosis of congenital motor nystagmus can be made. However, some diseases such as OA1 can be ignored or misdiagnosed. In general, OA1 is characterized by presence of photophobia, congenital nystagmus, strabismus, iris translucency, hypopigmentation of the ocular fundus, foveal hypoplasia, and impaired vision [23]. In African-American males, iris color is usually brown with little iris translucency (compared to Caucasians where iris translucency is more common) and individuals with darker skin may have scattered hypopigmented macules, but this is rarely seen in the skin of Caucasian individuals [24], [25]. The characteristics of OA1 have not been well defined in Asians. There were Chinese pedigrees of congenital nystagmus reported showing that the patients in these families had very similar symptoms as those in our pedigree. It is interesting to reevaluate these pedigree to make sure the diagnosis of “congenital nystagmus”, not “ocular albinism”, is correct, and the impression that OA1 has rarely seen in China is correct.

In summary, this study adds a novel nonsense mutation to the existing spectrum of GPR143 mutations in Chinese families with X-linked OA1. The specific molecular mechanism by which these GPR143 mutations result in OA1 is still unknown, further functional studies are needed to provide new insights to this inherited ocular disease.

Acknowledgments

The authors are deeply grateful to all the family members of this pedigree for their cooperation in this study.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC grant no. 30901635 and 81000370), from Research to Prevent Blindness. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Bassi MT, Schiaffino MV, Renieri A, De Nigris F, Galli L, et al. (1995) Cloning of the gene for ocular albinism type 1 from the distal short arm of the X chromosome. Nat Genet 10: 13–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kerrison JB, Vagefi MR, Barmada MM, Maumenee IH (1999) Congenital motor nystagmus linked to Xq26-q27. Am J Hum Genet 64: 600–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Charles SJ, Green JS, Grant JW, Yates JR, Moore AT (1993) Clinical features of affected males with X linked ocular albinism. Br J Ophthalmol 77: 222–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Faugere V, Tuffery-Giraud S, Hamel C, Claustres M (2003) Identification of three novel OA1 gene mutations identified in three families misdiagnosed with congenital nystagmus and carrier status determination by real-time quantitative PCR assay. BMC Genet 4: 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Creel D, O’Donnell FE Jr, Witkop CJ Jr (1978) Visual system anomalies in human ocular albinos. Science 201: 931–933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Preising M, Op de Laak JP, Lorenz B (2001) Deletion in the OA1 gene in a family with congenital X linked nystagmus. Br J Ophthalmol 85: 1098–1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schiaffino MV, Bassi MT, Galli L, Renieri A, Bruttini M, et al. (1995) Analysis of the OA1 gene reveals mutations in only one-third of patients with X-linked ocular albinism. Hum Mol Genet 4: 2319–2325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fang S, Guo X, Jia X, Xiao X, Li S, et al. (2008) Novel GPR143 mutations and clinical characteristics in six Chinese families with X-linked ocular albinism. Mol Vis 14: 1974–1982. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schorderet DF, Tiab L, Gaillard MC, Lorenz B, Klainguti G, et al. (2007) Novel mutations in FRMD7 in X-linked congenital nystagmus. Mutation in brief #963. Online. Hum Mutat 28: 525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Peng Y, Meng Y, Wang Z, Qin M, Li X, et al. (2009) A novel GPR143 duplication mutation in a Chinese family with X-linked congenital nystagmus. Mol Vis 15: 810–814. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Preising MN, Forster H, Gonser M, Lorenz B (2011) Screening of TYR, OCA2, GPR143, and MC1R in patients with congenital nystagmus, macular hypoplasia, and fundus hypopigmentation indicating albinism. Mol Vis 17: 939–948. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Camand O, Boutboul S, Arbogast L, Roche O, Sternberg C, et al. (2003) Mutational analysis of the OA1 gene in ocular albinism. Ophthalmic Genet 24: 167–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schnur RE, Gao M, Wick PA, Keller M, Benke PJ, et al. (1998) OA1 mutations and deletions in X-linked ocular albinism. Am J Hum Genet 62: 800–809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. d’Addio M, Pizzigoni A, Bassi MT, Baschirotto C, Valetti C, et al. (2000) Defective intracellular transport and processing of OA1 is a major cause of ocular albinism type 1. Hum Mol Genet 9: 3011–3018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Oetting WS (2002) New insights into ocular albinism type 1 (OA1): Mutations and polymorphisms of the OA1 gene. Hum Mutat 19: 85–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Liu JY, Ren X, Yang X, Guo T, Yao Q, et al. (2007) Identification of a novel GPR143 mutation in a large Chinese family with congenital nystagmus as the most prominent and consistent manifestation. J Hum Genet 52: 565–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhou P, Wang Z, Zhang J, Hu L, Kong X (2008) Identification of a novel GPR143 deletion in a Chinese family with X-linked congenital nystagmus. Mol Vis 14: 1015–1019. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mayeur H, Roche O, Vetu C, Jaliffa C, Marchant D, et al. (2006) Eight previously unidentified mutations found in the OA1 ocular albinism gene. BMC Med Genet 7: 41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schiaffino MV, d’Addio M, Alloni A, Baschirotto C, Valetti C, et al. (1999) Ocular albinism: evidence for a defect in an intracellular signal transduction system. Nat Genet 23: 108–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lopez VM, Decatur CL, Stamer WD, Lynch RM, McKay BS (2008) L-DOPA is an endogenous ligand for OA1. PLoS Biol 6: e236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ilia M, Jeffery G (2000) Retinal cell addition and rod production depend on early stages of ocular melanin synthesis. J Comp Neurol 420: 437–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ilia M, Jeffery G (1999) Retinal mitosis is regulated by dopa, a melanin precursor that may influence the time at which cells exit the cell cycle: analysis of patterns of cell production in pigmented and albino retinae. J Comp Neurol 405: 394–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rosenberg T, Schwartz M (1998) X-linked ocular albinism: prevalence and mutations–a national study. Eur J Hum Genet 6: 570–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. O’Donnell FE Jr, Hambrick GW Jr, Green WR, Iliff WJ, Stone DL (1976) X-linked ocular albinism. An oculocutaneous macromelanosomal disorder. Arch Ophthalmol 94: 1883–1892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. O’Donnell FE Jr, Green WR, Fleischman JA, Hambrick GW (1978) X-linked ocular albinism in Blacks. Ocular albinism cum pigmento. Arch Ophthalmol 96: 1189–1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]