Abstract

Allicin was discussed as an active compound with regard to the beneficial effects of garlic in atherosclerosis. The aim of this study was to investigate the cholesterol-lowering properties of allicin. In order to examine its effects on hypercholesterolemia in male ICR mice, this compound with doses of 5, 10, or 20 mg/kg body weight was given orally daily for 12 weeks. Changes in body weight and daily food intake were measured regularly during the experimental period. Final contents of serum cholesterol, triglyceride, glucose, and hepatic cholesterol storage were determined. Following a 12-week experimental period, the body weights of allicin-fed mice were less than those of control mice on a high-cholesterol diet by 38.24 ± 7.94% (P < 0.0001) with 5 mg/kg allicin, 39.28 ± 5.03% (P < 0.0001) with 10 mg/kg allicin, and 41.18 ± 5.00% (P < 0.0001) with 20 mg/kg allicin, respectively. A decrease in daily food consumption was also noted in most of the treated animals. Meanwhile, allicin showed a favorable effect in reducing blood cholesterol, triglycerides, and glucose levels and caused a significant decrease in lowering the hepatic cholesterol storage. Accordingly, both in vivo and in vitro results demonstrated a potential value of allicin as a pronounced cholesterol-lowering candidate, providing protection against the onset of atherosclerosis.

1. Introduction

Atherosclerosis (AS) is one of the major risk factors in the development of hypertension and cardiovascular diseases. It is the narrowing or occlusion of the arteries by plaque, which consists of cholesterol, platelets, monocyte/macrophages, calcium, aggregating proteins, and other substances. Morbidity of AS-induced coronary heart disease (CHD) gradually elevates annually due to the improvement of life standard and the change of lifestyle in recent years. However, the mechanism of the onset and development of atherosclerotic lesions are not completely understood until now. Many complicated factors interaction and interrelated biological processes contribute to AS. Among these, high plasma levels of low-density lipoprotein (LDL), especially its oxidized form (ox-LDL), and activation of the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) are considered to be the key influencing factor of the generation and development of AS [1, 2].

Recently, various natural products have emerged as active ingredients effective in controlling of AS [3, 4]. The medicinal use of garlic (Allium sativum) has been known since the Ancient Egyptian era. For centuries, garlic was used for treating high blood pressure in China and Japan. Its reported beneficial effects include detoxification, antioxidation, antifungal, antibacterial activity, tumour suppression, and prevention of heart disease [5]. In relation to heart disease, a major part of these publications deals with the beneficial effect on the cardiovascular system, mainly related to AS. Garlic has been shown to alter blood lipids [6], decrease blood coagulability [7], and inhibit cell proliferation [8, 9]. Furthermore, garlic has been found to act as an antihypertensive agent [10] and has been officially recognized as the treatment of hypertension by the Japanese Food and Drug Administration [11]. Although the data available today suggest that garlic contains biologically active compounds which are beneficial in cardiovascular disease like AS, the question about the active principles and their mechanism of action is still not settled [5, 12].

Allicin ((R,S)-diallyldisulfid-S-oxide), one of the sulfur compounds from garlic, is formed by the action of the enzyme alliinase on alliin. It possesses antioxidant activity and is shown to cause a variety of actions potentially useful for human health [12]. Allicin exhibits hypolipidemic, antiplatelet, and procirculatory effects. Moreover, it demonstrates antibacterial, anticancer, and chemopreventive activities.

The background and the fact mentioned above focused our interest on the question of whether the known constituent of processed garlic, allicin, which is discussed as an active component with regard to the beneficial effects of garlic preparation, has an effect on AS. Most previous studies used various garlic preparations in which allicin levels were not well defined. In the present study, we investigated the body weight, feed intake, and lipid profile in plasma, following hepatic cholesterol storage changes in the experimental model of hypercholesterolemic ICR mice, to evaluate whether application of a known amount of pure allicin has a beneficial effect on formation of fatty streaks (AS) and blood lipid levels in mice.

2. Results

2.1. Changes in Body Weight and Feed Intake

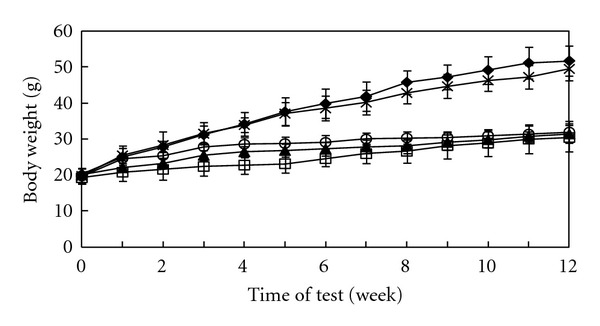

The oral administration of allicin to hypercholesterolemic ICR mice for 12 weeks resulted in a significant reduction in the body-weight gain in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 1). The body weight increased from 19.70 ± 2.23 g, 20.07 ± 0.44 g, and 19.22 ± 1.67 g at the start of the study to 31.93 ± 3.01 g, 31.39 ± 2.42 g, and 30.41 ± 3.98 g at the termination in the groups administered with doses of 5, 10, and 20 mg/kg allicin, respectively. Three test groups yielded reductions in body weight gain of 38.24 ± 7.94% (P < 0.0001), 39.28 ± 5.03% (P < 0.0001), and 41.18 ± 5.00% (P < 0.0001), respectively, as compared to the high-cholesterol control. The high-cholesterol diet alone yielded no difference in body weight gain when compared to the normal group (fed with a regular chow diet), indicating that the supplementation of cholesterol itself had no appreciable effect on body weight gain.

Figure 1.

Body weight changes (n = 6). Allicin was administered with doses (p.o.) of 0 (◆), 5 (○), 10 (▲), and 20 (□) mg/kg, respectively; the high cholesterol diet was fed throughout the test. The regular chow diet group (×) received no allicin treatment. The data are expressed as mean ± S.D. and are considered to be significantly different at P < 0.05 by the unpaired Student's t-test; P < 0.01 (from the 2th week of test) in 5 mg/kg allicin group; P < 0.0001 (from 1th week of test) in 10 and 20 mg/kg allicin groups.

A similar decline was seen in the daily food consumption of allicin treatment (Table 1). In contrast to a previous report [13], our observations demonstrated a significant decrease in food consumption in a dose-dependent manner. This tendency was most pronounced in the first two weeks of the test. From that point on, it steadily regressed toward the control value until the end of the test period except in the 20 mg/kg allicin group, where the food intake remained somewhat lower than in the control group throughout the experiment. At the 12th week of the test, the relative mean feed intake was 82.0 ± 4.7%, 80.1 ± 4.3% and 67.7 ± 2.4%, of the high cholesterol control in 5, 10, and 20 mg/kg allicin-administered groups, respectively.

Table 1.

Food intake efficiency during allicin administration (n = 6).

| Week | 1 | 2 | 3 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controld | 100 ± 2.1 | 100 ± 3.7 | 100 ± 1.4 | 100 ± 4.9 | 100 ± 6.0 |

| 5 mg/kg allicine | 90.3 ± 2.7a | 88.1 ± 4.2 | 80.0 ± 2.3a | 70.7 ± 5.9a | 82.0 ± 4.7 |

| 10 mg/kg allicine | 54.3 ± 0.5b | 74.2 ± 11.7a | 68.9 ± 1.6b | 80.5 ± 3.1a | 80.1 ± 4.3 |

| 20 mg/kg allicine | 42.0 ± 1.3c | 65.5 ± 5.7b | 53.0 ± 3.3b | 65.4 ± 3.2b | 67.7 ± 2.4a |

| Normal (regular diet)e | 89.9 ± 12.8a | 85.6 ± 2.6a | 82.3 ± 4.0a | 93.4 ± 14.8 | 82.7 ± 15.9 |

The data are mean ± S.D. and significantly different at a P < 0.05, b P < 0.01, and c P < 0.001 by the unpaired Student's t-test.

dThe high cholesterol control group, 200 μL PBS (pH 7.4) was served instead of allicin as a negative control.

eThe results are expressed as % of the high cholesterol control.

2.2. Biochemical Analysis of the Serum.

Biochemical parameters in mouse plasma and lipoproteins at the end of the study period were shown in Table 2. As shown in the results, the high-cholesterol diet group obtained an elevated TC, TG, GLU, and LDL-C, but a decreased HDL-C, suggesting an effective induction of hypercholesterolemia by supplementation of cholesterol in the diet, was effectively established in ICR mice. The allicin administration in doses of 5, 10, and 20 mg/kg lowered the elevated TC to 75.94%, 56.92%, and 64.77% of high-cholesterol control, respectively. A similar decrease was seen in LDL-C level; the concentrations of which declined to 57.92%, 56.83%, and 43.72% of control, respectively. The concentrations of HDL-C in all the allicin-treated animals, however, revealed no significant differences except 5 mg/kg group. Table 2 also showed that allicin administration lowered the elevated TG values to 63.03~89.57% and GLU levels to 57.53~62.00% of high-cholesterol control, respectively.

Table 2.

Serum parameters after 12-week allicin administration (n = 6, mM).

| Parameter | 5 mg/kg | 10 mg/kg | 20 mg/kg | Controlc | Normal (regular diet) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-cholesterol diet (allicin administered) | |||||

| TC | 43.91 ± 4.21b | 32.91 ± 1.34b | 37.45 ± 0.80b | 57.82 ± 3.51b | 32.99 ± 0.55 |

| TG | 1.66 ± 0.34a | 1.33 ± 0.11b | 1.89 ± 0.19b | 2.11 ± 0.35b | 1.04 ± 0.23 |

| GLU | 8.73 ± 0.49 | 8.22 ± 1.52 | 8.10 ± 0.14 | 14.08 ± 3.16b | 8.38 ± 0.75 |

| HDL-C | 1.25 ± 0.20a | 1.71 ± 0.59 | 1.60 ± 0.45 | 1.61 ± 0.16 | 1.94 ± 0.22 |

| LDL-C | 1.06 ± 0.52a | 1.04 ± 0.22a | 0.80 ± 0.15a | 1.83 ± 0.50 | 1.57 ± 0.43 |

The data are mean ± S.D. and significantly different at a P < 0.05 and b P < 0.01 by the unpaired Student's t-test.

TC: total cholesterol, TG: triglyceride, GLU: plasma glucose, HDL-C: high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

cThe high cholesterol control group, 200 μL PBS (pH 7.4) was served instead of allicin as a negative control.

2.3. Atherosclerotic Pathological Changes in the Liver

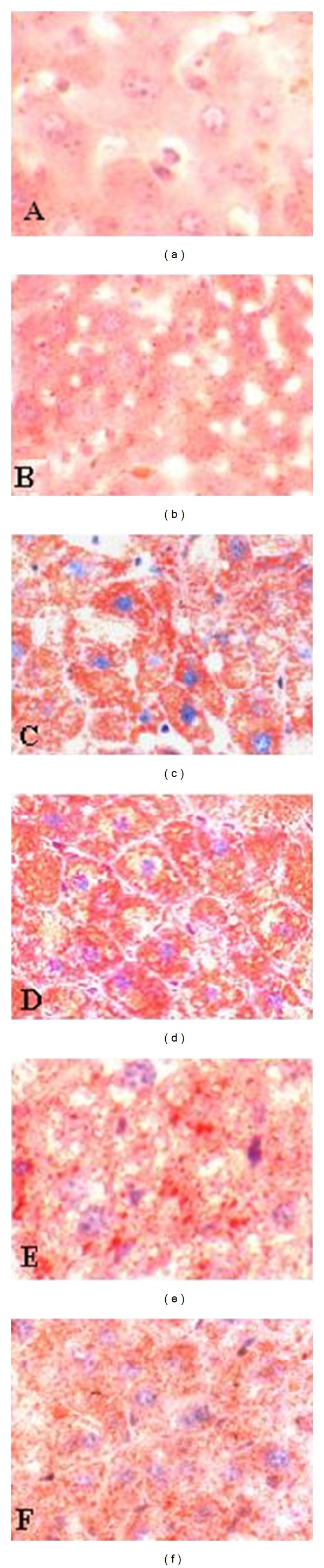

High cholesterol diet stimulation could promote hyperlipidemia, aggravated pathological changes of the liver, and even developed AS in the animals. Based on the results, the morphology of hepatic cells in allicin-administered groups showed obvious pathological changes in a dose-dependent manner compared with that of the high-cholesterol control group (Figure 2). The lipid accumulation in hepatic cells in allicin administered groups became smaller and less than those of mice given by PBS as a placebo. However, there were no significant changes accompanied with fatty alteration and accretion of cells' volume in the normal group, compared to the mice at 5 weeks of age.

Figure 2.

Photomicrographs of the section surface of livers stained with Oil Red O. (a) ICR mice (5 weeks age), fed with high cholesterol diet for one week before test; (b) normal group (17 weeks age), fed with a regular chow diet for 12 weeks; (c) high cholesterol control group (17 weeks age), fed with high cholesterol diet plus PBS for 12 weeks; (d) 5 mg/kg allicin administered group (17 weeks age), fed with high cholesterol diet for 12 weeks; (e) 10 mg/kg allicin administered group (17 weeks age), fed with high cholesterol diet for 12 weeks; (f) 20 mg/kg allicin administered group (17 weeks age), fed with high cholesterol diet for 12 weeks. Magnification: ×400.

3. Discussion

In recent years, remarkable progress has been made in the prevention and treatment of AS. Atherosclerotic diseases such as ischemic heart disease, stroke, and peripheral arterial disease are associated with high serum cholesterol, male gender, age, hypertension, cigarette smoking, diabetes, and so forth. Reduction in the concentration of blood lipids, especially cholesterol, is a major goal in several primary and secondary prevention initiatives. Therefore, the approaches to the prevention and treatment of atherosclerotic diseases are based primarily on the reduction of risk factors or rather modifiable factors such as hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and diabetes. This approach can be regarded as indirect antiatherosclerotic therapy.

Several studies have suggested that garlic may have beneficial effects on plasma cholesterol levels [14–16], while other studies found no influence [15–18]. We suggest that the composition and quantity of sulfur components of different protocol designs of garlic preparations used in various studies and the different mouse models used could account in part for the inconsistent findings. The pharmacological activities of garlic are attributed to the thiosulfinate compounds, of which allicin is approximately 75% [17]. Therefore, garlic antiatherosclerotic properties are mainly attributed to allicin. The use of pure allicin to study the atheroprotective effect of garlic is reasonable.

In the present study, by using pure allicin, we could investigate the effect of a well-defined component of garlic on AS and to seek for possible mechanisms of its antiatherogenic activity. Authors of many studies have shown the relationship between high-cholesterol levels, especially HDL-C and LDL-C, and the development of AS [18]. The high-cholesterol diet could induce a rise in blood cholesterol level to more physiologic levels, for which the rise became unphysiologic [19]. We chose not to use the transgenic mouse models of AS, although they resemble human AS better, because these models have a very strong phenotype and therefore might not be the best model for the proof of the current hypothesis. Results here demonstrated that the daily administration of pure allicin to ICR mice had a beneficial effect on the lipid profile, causing a distinct decrease in the serum TC, LDL-C, and accordingly a certain amount of decrease in the level of TG and GLU. The reduction in LDL-C was more pronounced than that of any other type of cholesterol. Since the concentration of HDL-C was not significantly changed, the cholesterol-lowering effect was in fact exclusively attributed to the decline of LDL-C, making the most characteristic changes involved in cholesterol modulation by allicin. Similar results that allicin exerted a beneficial effect on the lipid profile in hyperlipidemic rabbits had been previously reported [20].

On the other hand, the results also showed a significant decrease in lowering the hepatic cholesterol storage as compared with the controls. The lipid accumulation in hepatic cells has decreased as well, suggesting that allicin alleviated liver stress related to hypercholesterolemia and thus was advantageous to prevent from becoming a fatty liver.

Moreover, food consumption in allicin-treated animals showed a remarkable decline in a dose-dependent manner. Food consumption can play a role in cholesterol homeostasis as an independent influential factor. Since the restriction in food intake is also correlative to blood cholesterol reduction, it is quite possible that allicin has affected cholesterol homeostasis by a simple but efficient way of food intake suppression, as well as the change of body weight. And the actions of the cholesterol lowering presented in this paper would endow more nutritional and therapeutic value with allicin.

In summary, the present study confirmed and extended the understanding that allicin may beneficially affect the risk factors for AS—hyperlipidemia and attribute to lower the hepatic cholesterol storage. Thus, the active component allicin could potentially provide protection against the onset of AS. However, it is noteworthy that allicin is very reactive and rapidly converted to its metabolites [21], which may limit its biological activity. Further studies to elucidate the exact mechanism and the molecular basis of action of allicin on various animal species and in particular on humans are required.

4. Subjects and Methods

4.1. Preparation of Allicin

Allicin, synthesized compound with purity more than 95%, was obtained from Lichtwer Pharma GmbH (Germany) and dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The solution was stored in dark at 4°C until use (not more than 3 months). The chemical stability of allicin was assessed using HPLC and quantitatively determined at particular time intervals.

4.2. Oral Administration of Allicin to Hypercholesterolemic ICR Mice

Male ICR mice (3 weeks, 10 ± 2 g) were provided by the Animal Center, Academy of Chinese Traditional Medicine, Zhejiang, China. All mice were raised in a 12/12-hour light-dark cycle room with controlled temperature (21–23°C) and humidity (50–60%). The mice were fed two kinds of diet. The atherogenic high-cholesterol diet contained 15.75% fat (43% saturated fat) and 1.25% cholesterol (TD88137; Harlan). The regular chow diet consisted of 4.5% fat by weight (0.02% cholesterol) (TD19519; Koffolk). To minimize oxidation, the diets were stored in the dark at 4°C until use. The animals were given ad libitum with the regular chow diet and tap water for one week prior to any experiment. Then after the mice had been fed with high-cholesterol diet for one week, only those with over 200 mg/dL of blood cholesterol were selected for use in the experiment.

Some sources recommend that allicin should be used in high doses for medicinal purposes [13, 22]. In our preliminary study, three means of administration, intraperitoneal (ip), intravenous (iv) and oral (po) were tested for allicin. For oral administration for the dose-range experiment, higher concentrations of allicin-administered op (25 mg/kg/day) caused discomfort to the animals and were discontinued. And a regimen of 2 mg/kg/day was ineffective. We therefore tested a modified version of the allicin po regimen. Twenty-four selected mice were divided into four groups (n = 6) by randomization, three allicin test groups and one high-cholesterol control group. To the three test groups, 200 μL allicin solution in PBS was orally administered to correspond to 5, 10, or 20 mg allicin/kg body weight once per day for a period of 12 weeks (the amount of allicin administered had been found to be safe in a preliminary study). To the high-cholesterol control group, 200 μL PBS (pH 7.4) was served instead of allicin as a negative control. All the above animals were provided with the high-cholesterol diet throughout the animal test. A normal group (n = 6) fed with a regular chow diet was used for comparison and was supplied with the same volume of PBS (pH 7.4) instead of allicin. The mice were observed at least twice a day for clinical abnormalities.

4.3. Body Weight and Feed Intake

During the 12-week treatment, all mice appeared healthy and there was no evidence of toxicity. The body weight was recorded once weekly and feed intake daily. The feed intake efficiency in each group was evaluated by monitoring the feed consumption (g) in each cage for two consecutive days and was calculated per animal per day basis.

4.4. Collection of the Serum and Determination of Serum Parameters

The animals were kept at the above regimen and fed the diet as indicated above for a period of 12 weeks. At the end of the experimental period, the mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation after 16 hours of fasting. Blood samples were collected by cardiac puncture and allowed to clot for 2 h at room temperature, followed by centrifugation at 3500 xg for 10 min to obtain the serum. It was separated and stored at −80°C until analysis. The levels of total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG), glucose (GLU), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) were measured in the serum of mice using an automated enzymatic technique (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany) [23].

4.5. Assessment of AS in the Liver

The livers were also removed at the time of sacrifice for evaluating the formation of fatty streaks (AS). After thoroughly cleaning the peripheral fat, the livers were excised, weighed, and placed into individual vials containing physiologic saline (0.9%) and iced for about 2 h. The livers were prepared for sectioning by removing the lower portion with the plan of sectioning. Each liver was placed in a 15 mm × 15 mm × 15 mm cryomold mount containing octreotide (OCT, Miles Inc.) compound embedding medium, and then frozen with a cork back on liquid nitrogen. The embedded livers were kept in a freezer at −80°C until they were sectioned. Each liver was sectioned into 5 μm thick serial sections using a cryostat. Once the desired area had been located, 15 serial sections were obtained and stained with Oil Red O (Sigma, USA). These sections were viewed by light microscopy and were photographed using a Zeiss Photomicroscopy III camera.

4.6. Statistical Analysis

Each experiment was performed in triplicate and repeated at least twice. Values were expressed as means ± standard deviations (S.D.). Differences in mean values between groups were analyzed by a one-way analysis of variance and Dunnett's test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

This research was jointly supported by the Natural Scientific Foundation of Zhejiang Province (LY12C03009, Y5110135, and Y5110130). And the authors thank the Academy of Chinese Traditional Medicine, Zhejiang, China, for their technical assistance. And the authors are grateful to Professor Xiaodong Zheng of the Department of Food Science and Nutrition, Zhejiang University, China, for her valuable assistance.

References

- 1.Steinberg D, Parthasarathy S, Carew TE, Khoo JC, Witztum JL. Beyond cholesterol: modifications of low-density lipoprotein that increase its atherogenicity. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1989;320(14):915–924. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198904063201407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Esterbauer H, Gebicki J, Puhl H, Jurgens G. The role of lipid peroxidation and antioxidants in oxidative modification of LDL. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 1992;13(4):341–390. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(92)90181-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bramlett KS, Houck KA, Borchert KM, et al. A natural product ligand of the oxysterol receptor, liver X receptor. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2003;307(1):291–296. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.052852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Han LK, Zheng YN, Xu BJ, Okuda H, Kimura Y. Saponins from Platycodi radix ameliorate high fat diet-induced obesity in mice. Journal of Nutrition. 2002;132(8):2241–2245. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.8.2241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agarwal KC. Therapeutic actions of garlic constituents. Medicinal Research Reviews. 1996;16:111–124. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1128(199601)16:1<111::AID-MED4>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Phelps S, Harris WS. Garlic supplementation and lipoprotein oxidation susceptibility. Lipids. 1993;28(5):475–477. doi: 10.1007/BF02535949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Legnani C, Frascaro M, Guazzaloca G, Ludovici S, Cesarano G, Coccheri S. Effects of a dried garlic preparation on fibrinolysis and platelet aggregation in healthy subjects. Arzneimittel-Forschung/Drug Research. 1993;43(2):119–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee ES, Steiner M, Lin R. Thioallyl compounds: potent inhibitors of cell proliferation. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1994;1221(1):73–77. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(94)90218-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Orekhov AN, Tertov VV, Sobenin IA, Pivovarova EM. Direct anti-atherosclerosis-related effects of garlic. Annals of Medicine. 1995;27(1):63–65. doi: 10.3109/07853899509031938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al-Qattan KK, Alnaqeeb MA, Ali M. The antihypertensive effect of garlic (Allium sativum) in the rat two- kidney-one-clip Goldblatt model. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 1999;66(2):217–222. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(98)00173-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bolton S, Null G, Troetel WM. The medical uses of garlic—fact and fiction. American Pharmacy. 1982;NS22(8):40–43. doi: 10.1016/s0160-3450(16)31735-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reuter HD, Koch HP, Lawson LD. Therapeutic effects and applications of garlic and its preparations. In: Koch HP, Lawson LDGarlic L, editors. The Science and Therapeutic Application of Allium Sativum and Related Species. Baltimore, Md, USA: Williams and Wilkins; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abramovitz D, Gavri S, Harats D, et al. Allicin-induced decrease in formation of fatty streaks (atherosclerosis) in mice fed a cholesterol-rich diet. Coronary Artery Disease. 1999;10(7):515–519. doi: 10.1097/00019501-199910000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Banerjee SK, Maulik SK. Effect of garlic on cardiovascular disorders: a review. Nutrition Journal. 2002;1, article 1:1–14. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brace LD. Cardiovascular benefits of garlic (Allium sativum L.) Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2002;16(4):33–49. doi: 10.1097/00005082-200207000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kwon MJ, Song YS, Choi MS, Park SJ, Jeong KS, Song YO. Cholesteryl ester transfer protein activity and atherogenic parameters in rabbits supplemented with cholesterol and garlic powder. Life Sciences. 2003;72(26):2953–2964. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(03)00234-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Espirito Santo SMS, van Vlijmen BJM, Buytenhek R, et al. Well-characterized garlic-derived materials are not hypolipidemic in APOE*3-Leiden transgenic mice. Journal of Nutrition. 2004;134(6):1500–1503. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.6.1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watts GF, Lewis B, Brunt JNH, et al. Effects on coronary artery disease of lipid-lowering diet, or diet plus cholestyramine, in the St Thomas’ Atherosclerosis Regression Study (STARS) The Lancet. 1992;339(8793):563–569. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)90863-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paigen B, Morrow A, Brandon C. Variation in susceptibility to atherosclerosis among inbred strains of mice. Atherosclerosis. 1985;57(1):65–73. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(85)90138-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eilat S, Oestraicher Y, Rabinkov A, et al. Alteration of lipid profile in hyperlipidemic rabbits by allicin, an active constituent of garlic. Coronary Artery Disease. 1995;6(12):985–990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gonen A, Harats D, Rabinkov A, et al. The antiatherogenic effect of allicin: possible mode of action. Pathobiology. 2005;72(6):325–334. doi: 10.1159/000091330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coppi A, Cabinian M, Mirelman D, Sinnis P. Antimalarial activity of allicin, a biologically active compound from garlic cloves. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2006;50(5):1731–1737. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.5.1731-1737.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.George J, Afek A, Gilburd B, et al. Hyperimmunization of apo-E-deficient mice with homologous malondialdehyde low-density lipoprotein suppresses early atherogenesis. Atherosclerosis. 1998;138(1):147–152. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(98)00015-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]