Abstract

Flying insects typically possess two pairs of wings. In beetles, the front pair has evolved into short, hardened structures, the elytra, which protect the second pair of wings and the abdomen. This allows beetles to exploit habitats that would otherwise cause damage to the wings and body. Many beetles fly with the elytra extended, suggesting that they influence aerodynamic performance, but little is known about their role in flight. Using quantitative measurements of the beetle's wake, we show that the presence of the elytra increases vertical force production by approximately 40 per cent, indicating that they contribute to weight support. The wing-elytra combination creates a complex wake compared with previously studied animal wakes. At mid-downstroke, multiple vortices are visible behind each wing. These include a wingtip and an elytron vortex with the same sense of rotation, a body vortex and an additional vortex of the opposite sense of rotation. This latter vortex reflects a negative interaction between the wing and the elytron, resulting in a single wing span efficiency of approximately 0.77 at mid downstroke. This is lower than that found in birds and bats, suggesting that the extra weight support of the elytra comes at the price of reduced efficiency.

Keywords: beetles, flight, aerodynamics

1. Introduction

One of the most successful groups of flying animals is the beetles (Coleoptera), making up 40 per cent of all insects. One characteristic of beetles is that the first pair of wings has been sclerotized to become the elytra (wing coverts). The elytra protect the second, functional, wing pair and the dorsal side of the abdomen [1], and they reduce evaporation [2]. Most beetles hold their elytra extended during flight suggesting they affect the aerodynamics and hence the cost of flight. Although the aerodynamics of insect flight has been studied extensively [1,3–5], there is a relative paucity regarding aerodynamics of beetle flight ([1], but see [6–9]), and quantitative measurements of the flow generated by beetles are, to the best of our knowledge, lacking.

The ancestral state of winged insects is two pairs of wings of about similar size, comparable to those found in dragonflies [10] and fossil mayflies [11]. A double wing configuration with independently moving wings causes interactions between the wings. In beetles, the second wing pair is considerably longer than the elytra. This implies that, while the inner part of the wing system operates in a biplane or slotted arrangement, the outer part of the wing operates as a single wing. Although the inner part of the wing system may benefit from this configuration [7] and the efficiency of the flapping wings may theoretically increase, tip vortices of the elytra will be shed near the middle of the second wing pair, potentially reducing efficiency.

To determine the aerodynamic function and effect on performance of the elytra, we explore the wake of tethered dung beetles, and compare it with the wakes of other flying animals.

2. Material and methods

Six dung beetles (Heliocopris hamadryas) (electronic supplementary material, table S1) were tethered allowing only pitching motion and flown at speeds (U) of 6 (n = 5) and 7 m s–1 (n = 3) in a wind tunnel; Reynolds number range from 4500 to 7500 (Re = Uc/v, c = mean chord, v = kinematic viscosity).

Three-component velocity fields were measured using particle image velocimetry in a plane parallel to the Trefftz plane [y,z], x/c ≈ 8 downstream of the beetle. The sample rate (200 Hz) and wingbeat frequency (approx. 40 Hz) generated approximately five images per wingbeat. Nineteen sequences of 100 frames were analysed (box size 16 × 16, 50% overlap or 32 × 32, 75% overlap)—for details, see the electronic supplementary material. Two synchronized high-speed cameras filmed the beetles in side- and top views (electronic supplementary material, figure S1) for three-dimensional kinematics (electronic supplementary material, figure S2).

Bound circulation (Γ) was estimated at each position along y by integrating streamwise vorticity (ωx) along z within an area of interest incorporating the left wing's wake.

Wing beat period (T) was used to determine the relative timing within a wing beat (0 < τ = t/T < 1) of vector fields. For each y-position, a smoothing spline was fitted to the circulation of a normalized wing beat over the distance travelled, x(=UτT), and used to interpolate the bound circulation (Γ(x,y)) throughout the wingbeat (electronic supplementary material, figure S5). The vertical force (Fv) was estimated using an impulse (I) based vortex model:

where bw is the distance between the position along y and the body centre. Vertical force contribution of the wing tip/body vortices in isolation was estimated as:

where Γtip denotes tip vortex circulation and btr distance between tip and body vortex along y.

Downwash distribution (w(y)) was measured at mid-downstroke along a line between the wing tip and the centre of the body and throughout the wingbeat along a line connecting the tip vortex, elytra vortex, root vortex and the centre of the body. Span efficiency at mid-downstroke (ei) and throughout the wingbeat (ei,wb) was calculated as the ratio of the ideal induced power (Pi,ideal), based on uniform downwash generating the measured vertical force and the actual Pi based on the measured downwash ([12,13] and the electronic supplementary material).

3. Results and discussion

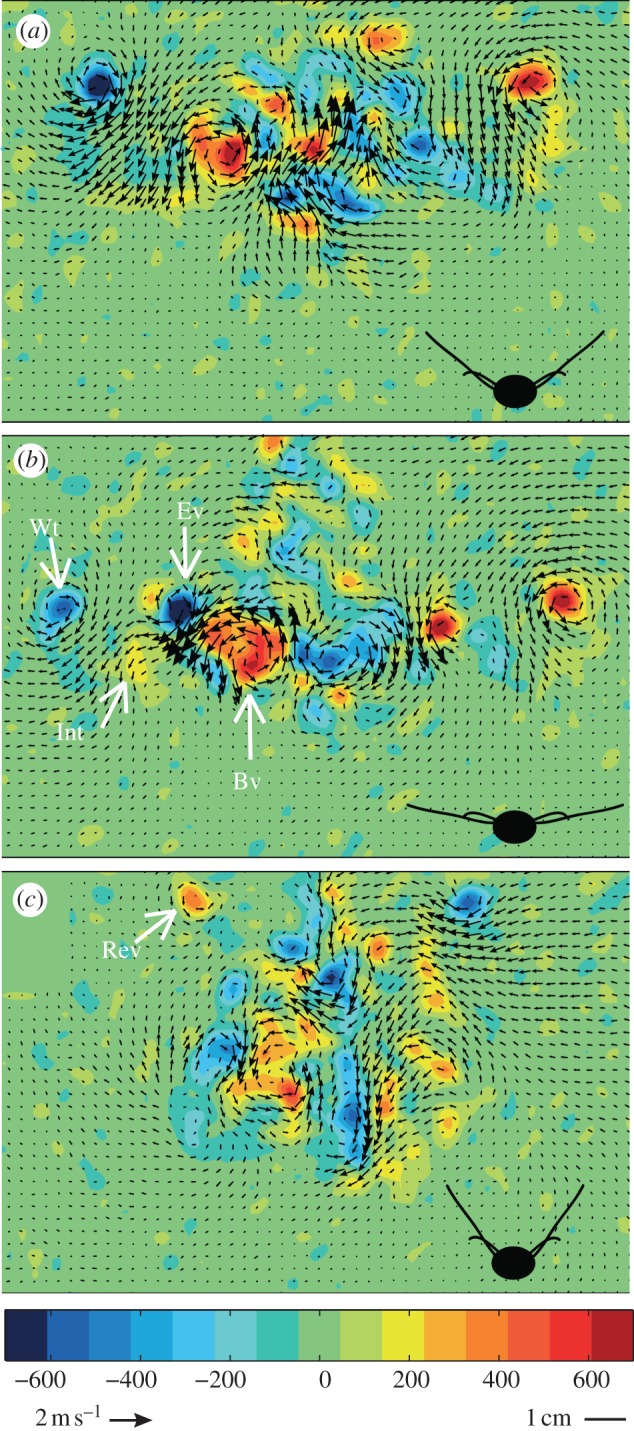

The elytra and wings both move downward during the downstroke. The elytra move in an almost vertical stroke plane relative to the body, while the wings move downwards and forwards with an inclined stroke plane (electronic supplementary material, figure S2). Beetles create a complex wake compared with previously studied animal wakes [3–4,12–17]. At the beginning of the downstroke, a tip vortex is formed in the proximity of the wingtip and a counter rotating vortex (body vortex) can be found between the tip vortex and the centre of the body (figure 1a). The body vortex migrates towards the body and remains throughout the wingbeat (figure 1). Shortly before mid-downstroke, a vortex of the same sign and approximate strength as the wingtip vortex becomes visible at mid-wing (figure 1b) and remains visible during the rest of the downstroke and for most of the upstroke (figure 1c). We name this vortex the elytron vortex (figure 2c). The downwash between the elytron vortex and the body vortex is strong compared with the downwash at the outer wing (figures 1b and 2c). Distal to the elytron vortex but proximal to the wingtip vortex, we observe a patch of vorticity of opposite sign to the wingtip vortex (figures 1b and 2c). This vortex patch is weaker than both the wingtip and elytron vortices and is present almost for as long as the elytron vortex is visible. We interpret this as a negative interaction (interaction vortex) between the elytron vortex and the flow generated by the wing. During the upstroke, the circulation of the tip and body vortex changes sign (figure 1c). The resulting vortex pair is similar to the distal vortex pair found at the end of the upstroke in the wakes of bats [12,14] and reflects a downward force, equal to approximately 3 per cent of the total upward force generated by the beetle.

Figure 1.

In-plane velocity and streamwise vorticity fields (ωx) from the transverse plane [y, z] behind beetle 2 flying at 7 m s−1 at (a) the beginning of downstroke, (b) mid-downstroke and (c) end of upstroke. Cartoons show approximate attitude of wings and elytra. Vorticity is colour-coded according to the colour bar below and vectors scaled according to the reference vector. Wt, wingtip vortex; Int, interaction vortex; Ev, elytron vortex; Bv, body vortex; Rev, reversed vortex during upstroke.

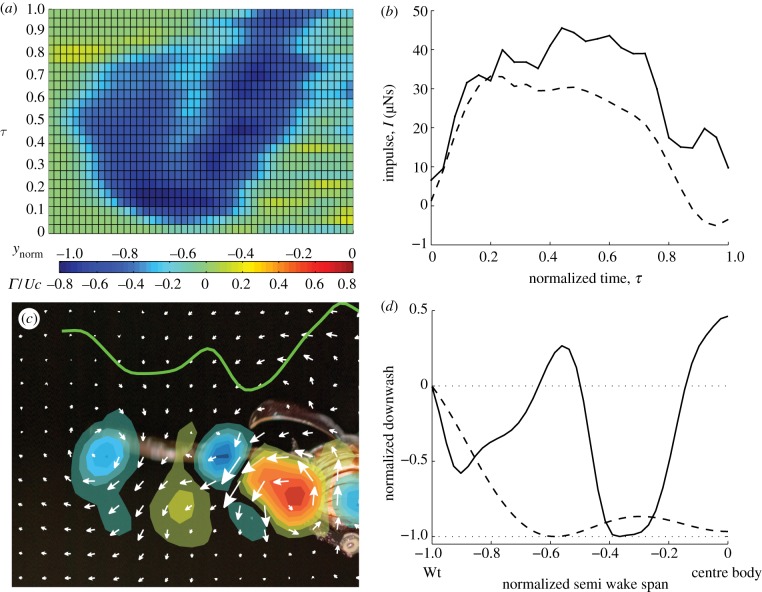

Figure 2.

(a) Circulation integrated from the tip towards the body, normalized by Uc, along the normalized semi-wing span (ynorm = −1 and 0 at wingtip and body centre, respectively) and normalized time (τ). Changes in circulation indicate the presence of a vortex in the wake (electronic supplementary material, figure S5). Circulation is scaled according to the colour bar. (b) Impulse generated over a normalized wing beat estimated using the total vorticity field (solid line) and using only the tip vortex and body vortex structures (dashed line). (c) Composite image showing the integrated spanwise circulation distribution (green line) at mid-downstroke (τ ≈ 0.5) with the corresponding velocity and vorticity field (only major vortex structures are shown) and beetle in the background for reference. Blue represents clockwise and red anti-clockwise vorticity. (d) Downwash distribution relative to maximum downwash along semi wake span (Wt, wing tip; centre body, wake symmetry plane) normalized by most distal downwash at mid-downstroke of a beetle (solid line) and a locust (dashed line) [5]. Data from five wingbeats of beetle 2 flying at 7 m s–1.

The flows generated by the elytra and the wing cannot be separated during the downstroke, owing to wake interactions. The presence of the elytra increases the circulation of the proximal part of the wing-elytra system when compared with the more distal part of the wing (figure 2a). There is also a notable interaction between the elytron vortex and the flow over the wing, causing a reduction in the integrated circulation of the central part of the wing configuration (figure 2a). To determine the net aerodynamic effect of the elytra, we estimated the vertical force generated by the wingtip-body vortex system (assuming no lift generated by the body), and compared it with the vertical force generated by the complete vortex structure. The force generated by the combined elytra-hind wing configuration is 36.2 ± 12.8% and 57.8 ± 16.7% (mean ± s.e.m.) (figure 2b; electronic supplementary material, table S2) higher than for the wingtip-body vortex system at U = 6 and 7 m s–1, respectively. The elytra thus add significantly to the weight support of the beetle.

The lowest induced power for a given lift is generally associated with an elliptical spanwise circulation distribution and a uniform downwash in planar, non-flapping wings [18]. However, in flapping wings, generating both lift and thrust, including studies of animal flight, the distribution generating the minimum induced power may look quite different from the ideal distribution. For example, theoretical models of flapping flight indicate that the optimal distribution includes a reduction in the circulation over the body during the downstroke [19]. There is also the possibility that unsteady mechanisms, such as leading edge vortices, may result in a stronger spanwise gradient in circulation. However, the spanwise circulation distribution observed in the dung beetles is more complex, owing to the presence of the elytra (figure 2a). When moving from the wingtip towards the body at mid-downstroke, the integrated circulation increases, then decreases, increases again near the elytron vortex and finally decreases to almost zero at the centre of the body (figure 2a,c). This circulation distribution, with multiple increases and decreases along the span, results in large deviations from the single downwash reduction behind the body associated with flapping wings (figure 2d). A measure for the variation in downwash is the span efficiency, ei [12,18], where uniform downwash represents ei = 1. For the flying beetles, we estimate the wingbeat average span efficiency (ei,wb = 0.62 ± 0.015), and span efficiency at mid-downstroke (ei = 0.48 ± 0.056). These values are relatively low, which is partly owing to the flow generated by the body. As we are primarily interested in the effect of the elytra, we also calculated the span efficiency for a single wing (eis,wb = 0.66 ± 0.016, eis ± 0.77 ± 0.0098, see the electronic supplementary material) and compared with the available data in the literature. We estimated the eis at mid-downstroke in pied flycatchers (0.88 ± 0.0054) [13], in Pallas’ long-tongued bat (0.89 ± 0.0067), in the lesser long-nosed bat (0.86 ± 0.016) [12] and the desert locust [5] (0.85 ± 0.043), using the current method (see the electronic supplementary material). All the studies in this comparison were made closer than a wing span behind the wings, where roll up is still moderate, suggesting the results are comparable. The eis of beetles is lower than in the vertebrates, and lower than, but not separable from, the locust, owing to the uncertainty in the single sample size locust estimate (electronic supplementary material, figure S6).

Our sample size (n = 5 and 3 at 6 and 7 m s–1, respectively) advises against over-generalization, but the results indicate that the cost of the weight support added by the elytra is reduced aerodynamic efficiency. We suggest that when the wings are able to generate weight support in solitude, evolution would favour folding the elytra, resulting in higher efficiency. This behaviour can indeed be found in some groups of beetles (e.g. within Scarabaeidae and Buprestidae), which fold their elytra back over the body after the second wing pair has unfolded, allowing this prediction to be tested.

Acknowledgements

Research was funded by the Knut and Alice Wallenberg foundation to A.H., by the Swedish Research Council to L.C.J., A.H., M.D. and S.E. and by AFOSR to E.B. and M.D. This report received support from the Centre for Animal Movement Research (CAnMove) financed by a Linnaeus grant (349-2007-8690) from the Swedish Research Council and Lund University.

References

- 1.Dudley R. 2000. The biomechanics of insect flight: form, function, evolution, 1st edn. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dizer Y. B. 1955. On the physiological role of the elytra and sub-elytral cavity of the steppe and desert Tenebrionidae. Zoologicheskii Zhurnal SSR 34, 319–322 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bomphrey R. J., Lawson N. J., Taylor G. K., Thomas A. L. R. 2006. Application of digital particle image velocimetry to insect aerodynamics: measurements of the leading-edge vortex and near wake of a hawkmoth. Exp. Fluids 40, 546–554 10.1007/s00348-005-0094-5 (doi:10.1007/s00348-005-0094-5) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bomphrey R. J., Taylor G. K., Thomas A. L. R. 2009. Smoke visualization of free-flying bumblebees indicates independent leading-edge vortices on each wing pair. Exp. Fluids 46, 811–821 10.1007/s00348-009-0631-8 (doi:10.1007/s00348-009-0631-8) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bomphrey R. J., Taylor G. K., Lawson N. J., Thomas A. L. R. 2006. Digital particle image velocimetry measurements of the downwash distribution of a desert locust Schistocerca gregaria. J. R. Soc. Interface 3, 311–317 10.1098/rsif.2005.0090 (doi:10.1098/rsif.2005.0090) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grodnitsky D. L., Morozov P. P. 1995. The vortex wakes of flying beetles. Zoologichesky Zhurnal 74, 66–72 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Le T. Q., Byun D., Yoo Y. H., Ko J. H. 2009. Experimental and numerical investigation of beetle flight. In 2008 IEEE Int. Conf. on Robotics and Biomimetics, Bangkok, Thailand, vol. 1–4, pp. 234–239 New York, NY: IEEE [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sitorus P. E., Park H. C., Byun D., Goo N. S., Han C. H. 2010. The role of the elytra in beetle flight. I. Generation of quasi-static aerodynamic forces. J. Bionic Eng. 7, 354–363 10.1016/S1672-6529(10)60267-3 (doi:10.1016/S1672-6529(10)60267-3) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burton A. J., Sandeman D. C. 1961. The lift provided by the elytra of the rhinoceros beetle, Oryctes boas Fabr. S. Afr. J. Sci. 57, 107–109 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis R. B., Baldauf S. L., Mayhew P. J. 2010. Many hexapod groups originated earlier and withstood extinction events better than previously realized: inferences from supertrees. Proc. R. Soc. B 277, 1597–1606 10.1098/rspb.2009.2299 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.2299) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wootton R. J. 1981. Palaeozoic insects. Ann. Rev. Entomol. 26, 319–344 10.1146/annurev.en.26.010181.001535 (doi:10.1146/annurev.en.26.010181.001535) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muijres F. T., Spedding G. R., Winter Y., Hedenström A. 2011. Actuator disk model and span efficiency of flapping flight in bats based on time-resolved PIV measurements. Exp. Fluids 51, 511–525 10.1007/s00348-011-1067-5 (doi:10.1007/s00348-011-1067-5) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muijres F. T., Bowlin M. S., Johansson L. C., Hedenström A. 2011. Vortex wake, downwash distribution, aerodynamic performance and wingbeat kinematics in slow-flying pied flycatchers. J. R. Soc. Interface 9, 292–303 10.1098/rsif.2011.0238 (doi:10.1098/rsif.2011.0238) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hubel T. Y., Riskin D. K., Swartz S. M., Breuer K. S. 2010. Wake structure and wing kinematics: the flight of the lesser dog-faced fruit bat, Cynopterus brachyotis. J. Exp. Biol. 213, 3427–3440 10.1242/jeb.043257 (doi:10.1242/jeb.043257) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henningsson P., Spedding G. R., Hedenström A. 2008. Vortex wake and flight kinematics of a swift in cruising flight in a wind tunnel. J. Exp. Biol. 211, 717–730 10.1242/jeb.012146 (doi:10.1242/jeb.012146) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Altshuler D. L., Princevac M., Pan H., Lozano J. 2009. Wake patterns of the wings and tail of hovering hummingbirds. Exp. Fluids 46, 835–846 10.1007/s00348-008-0602-5 (doi:10.1007/s00348-008-0602-5) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johansson L. C., Hedenström A. 2009. The vortex wake of blackcaps (Sylvia atricapilla L.) measured using high-speed digital particle image velocimetry (DPIV). J. Exp. Biol. 212, 3365–3376 10.1242/jeb.034454 (doi:10.1242/jeb.034454) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spedding G. R., McArthur J. 2010. Span efficiencies of wings at low Reynolds numbers. J. Aircraft 47, 120–128 10.2514/1.44247 (doi:10.2514/1.44247) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hall K. C., Hall S. R. 2002. A rational engineering analysis of the efficiency of flapping flight. Progr. Astronaut. Aeronaut. 195, 249–274 [Google Scholar]