Abstract

Different species respond differently to environmental change so that species interactions cannot be predicted from single-species performance curves. We tested the hypothesis that interspecific difference in the capacity for thermal acclimation modulates predator–prey interactions. Acclimation of locomotor performance in a predator (Australian bass, Macquaria novemaculeata) was qualitatively different to that of its prey (eastern mosquitofish, Gambusia holbrooki). Warm (25°C) acclimated bass made more attacks than cold (15°C) acclimated fish regardless of acute test temperatures (10–30°C), and greater frequency of attacks was associated with increased prey capture success. However, the number of attacks declined at the highest test temperature (30°C). Interestingly, escape speeds of mosquitofish during predation trials were greater than burst speeds measured in a swimming arena, whereas attack speeds of bass were lower than burst speeds. As a result, escape speeds of mosquitofish were greater at warm temperatures (25°C and 30°C) than attack speeds of bass. The decline in the number of attacks and the increase in escape speed of prey means that predation pressure decreases at high temperatures. We show that differential thermal responses affect species interactions even at temperatures that are within thermal tolerance ranges. This thermal sensitivity of predator–prey interactions can be a mechanism by which global warming affects ecological communities.

Keywords: sustained locomotion, sprint performance, attack speed, predator escape, climate change

1. Introduction

Within-individual plasticity (acclimation) of physiological systems alters the thermal sensitivity of performance in response to chronic changes in temperature [1,2]. Acclimation can thereby compensate for the effect of thermal variation in the environment on physiological functions. Acclimation is now thought to be one of the most effective responses to human-induced global warming because it renders individuals more resilient to change [3–5]. Most studies of acclimation have concentrated on single species. However, organisms do not exist in isolation, and biological communities comprise numerous interactions within and between species. The outcomes of biotic interactions depend on the performance of individuals, so that interactions can be affected by environmental factors that modulate physiological performance. Predator–prey interactions depend on locomotion and its underlying physiological mechanisms [6], and in ectotherms it is likely that these interactions will be modified by the thermal environment. The thermal sensitivity of locomotor performance in ectotherms differs between species [7,8], and predators and their prey may respond differently to similar thermal changes [9,10]. Different responses of predator and prey species to thermal change can alter the success of predators in catching prey as a result of disproportional increases or decreases in prey and predator locomotor performance. Consequently, predation pressures may shift as a result of changes in environmental temperatures, and different thermal responses of species can influence the abundances of predators and prey, and therefore community structure. The aim of this study was to determine whether a predator and its prey respond differently to changes in temperature, and whether this affects the outcome of their interaction.

Locomotion is necessary for behaviours such as foraging and predator escape, and thermal acclimation of locomotor performance can affect fitness [11–13]. Predation may involve different types of locomotion, including an initial burst [14] followed by prolonged pursuit. As a result, both burst and sustained swimming may be important in determining predator success or prey escape. We chose Australian bass (Macquaria novemaculeata) as the predator and mosquitofish (Gambusia holbrooki) as its prey, because the species are sympatric over some of their range, and predation by bass could curtail the spread of invasive mosquitofish. However, in contrast to M. novemaculeata, which are restricted to coastal drainages in temperate regions of eastern Australia, mosquitofish occur across a wide range of thermal conditions ranging from the tropics and hot springs to cool mountain habitats [15,16]. It may be expected, therefore, that the thermal performance range and capacity for acclimation differ between these species. Hence, we tested the hypotheses that (i) G. holbrooki has a broader thermal locomotor performance range than M. novemaculeata, and (ii) that predator success will decline at the higher and lower ends of G. holbrooki's thermal performance range. We determined thermal performance curves for burst and sustained swimming of each species after acclimation to different temperatures to test whether the species respond differently to chronic changes in the thermal environment. We then determined thermal performance curves for predator motivation and success at catching prey.

2. Methods

(a). Study animals and acclimation

Juvenile Australian bass (M. novemaculeata; mean ± s.e. mass = 3.216 ± 0.197 g, mean ± s.e. total length = 5.869 ± 0.095 cm) of mixed sex were obtained from a fish farm (Searle Aquaculture, Palmers Island, NSW, Australia) and housed in plastic tanks (35 × 60 × 27 cm; 10 animals per tank). Mosquitofish (G. holbrooki; mean ± s.e. mass = 0.236 ± 0.010 g, mean ± s.e. total length = 2.692 ± 0.054 cm) were caught from the wild in the Sydney metropolitan area (151.183° E, 33.891° S) using hand nets. They were housed in plastic tanks (35 × 60 × 27 cm; 25 animals per tank) with both males and females (1 : 1) to simulate natural conditions; however, only adult males were used in the experiments, to avoid differences in behaviour and the effects of pregnancy on swimming performance [15]. All fish were housed in a constant 12 L : 12 D cycle that was maintained throughout experiments. Fish were kept for two weeks at 20°C to habituate to their new environment before acclimation treatments were started. Bass were fed pellets (Cichlid pellets, New Life Spectrum, Homestead, FL) daily and mosquitofish were fed fish flakes (Gourmet flake blend, Wardley Total Tropical, Secaucus, NJ) daily. Throughout the experiments, tanks were continuously aerated with sponge filters, and approximately one-third of water in all tanks was replaced weekly with aged, dechlorinated water at the same temperature.

Bass (n = 14 per acclimation treatment) and mosquitofish (n = 85 per acclimation treatment; adult males only) were acclimated to two constant temperatures—a ‘warm’ temperature treatment (water temperature: 25.0 ± 0.5°C) and a ‘cold’ temperature treatment (water temperature: 15.0 ± 0.5°C)—for four weeks. Both temperatures were within the seasonal extremes naturally experienced by both species, which range from 12 to 27°C in coastal water bodies and rivers (F. Seebacher 2011, unpublished data [16]). During acclimation treatments, bass were housed individually in plastic tanks (25 × 35 × 15 cm), and mosquitofish were kept in male and female (1 : 1) groups (25 × 35 × 15 cm; n = 10 per tank). Tanks were kept in a temperature-controlled room, and acclimation temperatures were reached by gradually increasing or decreasing water temperature by 2.5°C per day. The feeding regime for mosquitofish was the same as described earlier during acclimation treatments. However, after three weeks of acclimation, each bass was fed one mosquitofish per day to train bass to recognize mosquitofish as prey [17]; bass from both acclimation treatments readily ate one mosquitofish per day. All trials were conducted during daylight hours.

(b). Swimming performances

Burst and sustained swimming performances of both species from each acclimation treatment were measured at acute test temperatures of 10, 15, 20, 25 and 30°C. We chose these test temperatures because they include acclimation temperatures as well as temperatures above and below that allowed us to determine possible declines in performance at more extreme temperatures. To measure burst swimming velocity, individuals (bass: n = 14 per acclimation treatment; mosquitofish: n = 25 per acclimation treatment) were placed into a plastic tray (40 × 25 × 5 cm) filled with water to a depth of 3 cm and were allowed to equilibrate for 15 min. Burst swimming responses were initiated by startling individuals by lightly tapping their tail (enough to elicit an escape response) with a blunt metal probe. The ensuing responses were filmed from above with a camera (Quickcam Pro, Logitech, China) filming at 30 frames s−1, and analysed with video analysis software (Tracker; Open Source Physics, USA). We used bass repeatedly at each test temperature in random order; animals had 48 h rest between swimming trials [18], and swimming trials were conducted after predation experiments (see below). Individual mosquitofish were used only once. Three escape responses were measured for each individual, and the fastest velocity recorded was used as the maximum burst swimming performance [19].

Sustained swimming performance was measured as the critical sustained swimming speed (Ucrit), and was determined for individuals (n = 14 bass, n = 15 mosquitofish) used in fast start trials at each test temperature according to published protocols [20]. Briefly, swimming flumes consisted of a clear Perspex tube (150 × 50 mm) fitted over a submersible inline pump (12 V DC, iL500, Rule, Hertfordshire, UK) at one end, with a plastic grid separating the flume from the pump. The other end of the tube was filled with hollow straws to reduce turbulence. A DC power source (MP3090, Powertech, Sydney, NSW, Australia) was used to adjust flow speed, and flow in the flume was calibrated using a flow meter (FP101, Global Water, Gold River, CA, USA). Each fish was tested once at each test temperature, and Ucrit was determined as Ucrit = Uf + Tf/Ti × Ui, where Uf is the highest speed maintained for an entire interval (Ti = 5 min), Tf is the time until exhaustion in the final speed interval and Ui is the speed increment (2 BL s−1).

(c). Predator–prey interactions

Predator–prey interactions were determined at the same five test temperatures (10, 15, 20, 25 and 30 ± 0.5°C) as swimming performance, with 24 h between trials; the sequence of test temperatures was randomly selected. Bass from each acclimation treatment (n = 14) were placed individually into a plastic tank (35 × 25 × 20 cm; 10 cm depth) and allowed to equilibrate to the surroundings and the acute test temperature for 30 min. After 30 min, a mosquitofish from the same acclimation treatment was placed into the tank and confined to a clear cylindrical Perspex tube (150 × 50 mm) standing on its end in the middle of the tank. The mosquitofish were also allowed to equilibrate for 30 min, so that both fish had the opportunity to become aware of each other, but without direct access to one another. After this equilibration period, the Perspex tube was lifted, and interactions were filmed for 30 min using a digital camera (Quickcam Pro; 30 frames s−1) suspended above the behavioural arena. Fish were observed in real time from outside the experimental room to minimize disturbance and to monitor any injuries that may occur. After 30 min, both fish (if mosquitofish were not consumed) were removed and bass were returned to their holding tanks. Mosquitofish were not re-used during subsequent predation trials. Bass were re-used in subsequent swimming trials.

Videos were analysed to determine maximal attack velocities of bass and maximal escape velocities of mosquitofish in each interaction; we present attack and escape speeds as both absolute speeds (m s−1), to determine whether the likelihood of escape changes in different thermal environments, and as body lengths (BL) s−1 to compare with swimming trial results. In addition, we measured the time until the first predation attempt by bass; the maximum duration of all attempts made during each interaction, where duration of attempt was defined as the period from the onset of the attack until bass were stationary again; and the number of attempts per minute for each trial. Finally, we recorded the total number of successful captures.

(d). Statistical analysis

We used a PERMANOVA (Primer 6, ePrimer, UK) to analyse Ucrit and burst swimming performance measured in the swimming flume and arena, as well as attack and escape speeds during predation trials within each species with acclimation and test temperature as fixed factors. To compare Ucrit and burst swimming between species within acclimation treatments (i.e. compare cold-acclimated bass with cold-acclimated mosquitofish and warm-acclimated bass with warm-acclimated mosquitofish), we used species and test temperature as fixed factors. To estimate relative energy reserves of predators that could influence their motivation to capture prey, we calculated condition factors of bass as mass per total length3 × 100, and compared these before predation trials between acclimation treatments with t-tests.

We compared maximal attack velocities and maximal escape velocities with burst swimming velocities measured in the swimming arena (both measured in BL s−1) of warm-acclimated bass and warm-acclimated mosquitofish, respectively, using a PERMANOVA with experimental condition (predation trial versus swimming arena) and test temperature as fixed factors. We used a paired t-test to compare the maximal absolute (m s−1) attack speeds of bass with absolute escape speeds of mosquitofish at the two warmest temperatures.

For analyses of predation measures, we used a PERMANOVA with acclimation as a fixed factor and test temperature as a random factor; note that the range of test temperatures was 15–30°C for predation attempts, and we did not conduct predation trials of warm-acclimated fish at 10°C because mosquitofish did not swim at this temperature. To test the hypothesis that the number of successful captures depends on the frequency of attacks, we regressed the success rate of bass capturing the mosquitofish of the 10 independent predation trials as dependent variable against the average number of attacks per minute across all temperatures and acclimation treatments.

The truncated product method [21] was used to combine all the p-values in this study to determine whether there is a bias from multiple hypothesis testing. The truncated product method p-value was less than 0.0001, showing that the results are not biased. Raw data are available on request from the corresponding author.

3. Results

(a). Swimming performance

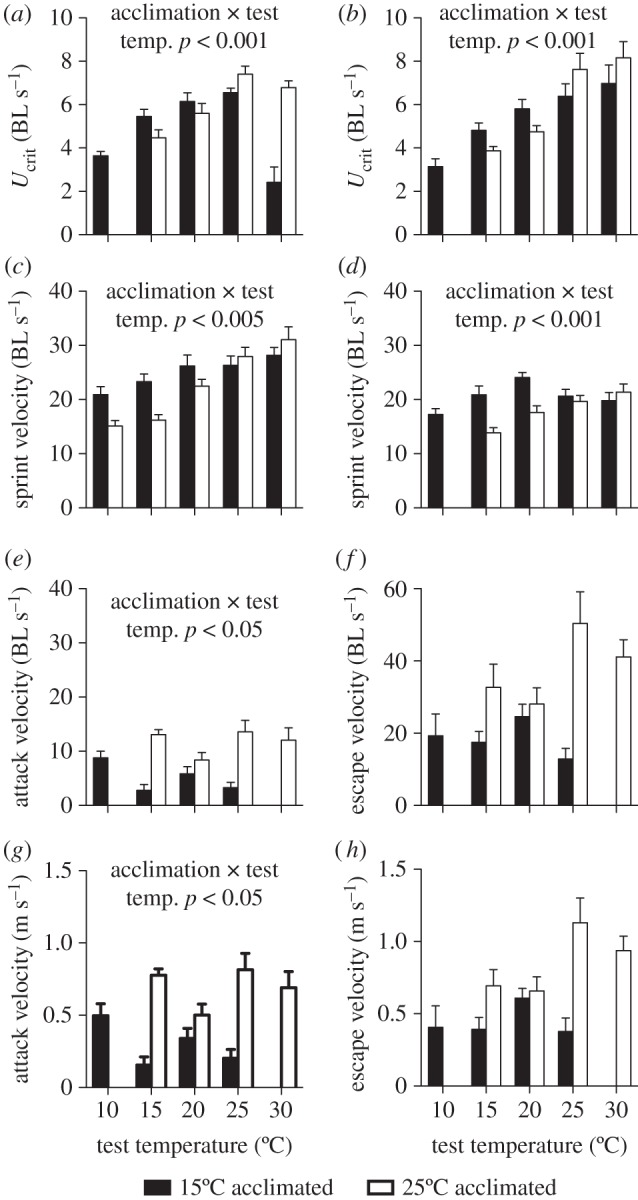

In bass, Ucrit of cold-acclimated fish decreased at the highest test temperatures, and that of warm-acclimated fish decreased at lower temperatures (interaction between acclimation and test temperature: F4,129 = 48.395, p < 0.001; figure 1a). Burst swimming performance in bass declined to a greater extent at low temperatures in warm-acclimated compared with cold-acclimated fish (interaction between acclimation and test temperature: F4,129 = 4.462, p < 0.05; figure 1c).

Figure 1.

(a,c,e,g) Swimming performance in bass and (b,d,f,h) mosquitofish. There were interactions between acclimation treatment and test temperatures for sustained swimming performance (Ucrit) in (a) bass and (b) mosquitofish, as well as for burst swimming in (c) bass and (d) mosquitofish. Similarly, there was an interaction between acclimation treatment and test temperature in attack speeds of (e) bass, but escape speeds of (f) mosquitofish did not change significantly with acclimation treatment or test temperature. Interestingly, attack speeds of bass were significantly lower than burst speeds measured in the swimming arena, but escape speeds of mosquitofish were significantly higher than burst speeds. Absolute escape speeds of (h) mosquitofish were significantly higher than attack speeds of (g) bass at 25°C and 30°C. Black bars represent cold-acclimated fish and white bars represent warm-acclimated fish. Means and s.e. are shown, and results of statistical analyses are indicated in each panel.

In mosquitofish, Ucrit declined to a greater extent in warm- compared with cold-acclimated fish at low temperatures, but it increased at warm temperatures in fish from both acclimation treatments (interaction between acclimation and test temperature: F4,140 = 29.385, p < 0.001; figure 1b). Similarly, burst swimming performance of cold-acclimated mosquitofish was higher at colder temperatures, but it was similar at the high temperatures (interaction between acclimation and test temperature: F4,240 = 108.22, p < 0.001; figure 1d).

There was an interaction between species and test temperature in Ucrit of cold-acclimated fish (F4,135 = 4.301, p < 0.001), but not of warm-acclimated fish (F4,135 = 1.4, p = 0.212); cold-acclimated bass showed a decrease in performance at warmer temperatures while cold-acclimated mosquitofish maintained high performance levels. Conversely, there was an interaction between species and test temperature in burst swimming velocity for warm-acclimated individuals (F4,185 = 99.307, p < 0.001), but not for cold-acclimated individuals (F4,185 = 1.531, p = 0.188); warm-acclimated mosquitofish did not swim at the coldest temperature.

(b). Attack and escape speeds

For bass attack speeds, there was an interaction between acclimation and test temperature (F2,40 = 3.851, p < 0.05; figure 1e), and performance declined at high or low temperatures for cold- and warm-acclimated fish, respectively. Maximal escape speeds of mosquitofish did not change with test temperature (F2,40 = 2.422, p = 0.073), but warm-acclimated fish were significantly faster than cold-acclimated animals (F1,40 = 10.15, p < 0.01); but there was no interaction (F4,40 = 2.422, p = 0.067; figure 1f).

Interestingly, maximum escape speeds of mosquitofish during predation trials were significantly higher than burst swimming performance determined in the arena (F1,120 = 58.802, p < 0.001), and there was a main effect of test temperature (F3,120 = 4.333, p < 0.001). In contrast, maximal attack speeds of bass were lower than burst swimming speeds measured in the arena (F1,76 = 78.255, p < 0.001), but temperature affected attack speeds and burst swimming in the arena differently (interaction: F3,76 = 5.989, p < 0.001).

The maximal absolute attack speeds of warm-acclimated bass were significantly lower than the maximal absolute escape speeds of warm-acclimated mosquitofish at the two warmest temperatures (figure 1g,h; 25°C: t6 = 2.629, p < 0.05; 30°C: t7 = 4.762, p < 0.05).

(c). Predator–prey interactions

Condition factors of bass did not differ between warm- (mean = 1.50 ± 0.062 s.e.) and cold-acclimated fish (mean = 1.39 ± 0.11 s.e.) at the end of the acclimation period (t = −0.94, p = 0.36). Warm-acclimated bass were quicker to attack compared with cold-acclimated fish (F1,40 = 12.39, p < 0.001; figure 2a), but there was no effect of test temperature (F4,40 = 0.512, p = 0.853) or an interaction (F2,40 = 0.158, p = 0.971). The maximum duration of attacks by bass was longer in warm-acclimated animals compared with cold-acclimated fish (F1,40 = 6.569, p < 0.01), but it did not change with test temperature (F4,40 = 0.762, p = 0.577), and there was no interaction (F2,40 = 1.097, p = 0.328; figure 2b). Warm-acclimated bass also made more attacks than cold-acclimated fish, particularly at warm temperatures, although the number of attacks decreased at the highest temperature (30°C; interaction between acclimation and test temperature: F3,68 = 2.452, p < 0.05; figure 2c). The success of bass in capturing their prey increased linearly with the number of attacks made per minute (r2 = 0.85, F1,8 = 45.94, p < 0.0001; figure 2d).

Figure 2.

Predator–prey interactions. (a) Warm-acclimated bass were quicker to attack than cold-acclimated fish, and (b) attacked for longer. (c) Warm-acclimated bass also made more attacks than cold-acclimated fish, particularly at warm temperatures, although the number of attacks decreased at the highest temperature. (d) The success of bass in capturing prey (the proportion of the ten independent predation trials in which bass captured a mosquitofish) increased linearly with the number of attacks made per minute; the regression line ±95% confidence intervals are shown. Black bars and circles represent cold-acclimated fish, and white bars and circles represent warm-acclimated fish. (a–c) Means and s.e. are shown, and results of statistical analyses are indicated in each panel.

4. Discussion

Thermal acclimation can affect fitness by its effects on individual performance during intraspecific aggressive interactions and reproduction [22,23]. Here, we have shown that in addition to its effect on interactions within species, thermal acclimation also modifies interactions between species. We show that bass were more resilient than mosquitofish at colder temperatures, but (unlike in bass) sustained performance of mosquitofish did not decline at warmer temperatures, and ultimately prey escape speed was greater than predator attack speed at high temperatures. Differences in the acclimation of locomotor performance between species may be due to differences in cellular biochemistry and regulatory processes, such as evolutionary differences in the regulatory mechanisms involved in mitochondrial bioenergetics and biogenesis [24,25]. Evolutionary theory predicts that animals experiencing greater within-generation variability in temperature also have greater capacity for thermal acclimation [26]. In an evolutionary sense, mosquitofish may be expected to acclimate better than bass because the species experiences a much wider and more variable range of temperatures, including greater short-term variation in shallower water [15]. However, even though thermal sensitivity curves differed, both species acclimated, so that evolutionary theory alone cannot explain thermal responses. This raises interesting questions about the enabling mechanisms underlying acclimation, which are poorly understood and may be an inherent property of thermoregulatory pathways [27].

Interestingly, both attack and escape speeds differed from burst swimming performances in the swimming arena, indicating that realized swimming performance depends on the role of the species in an ecological context [28]. Prey may be more motivated when pursued by a predator than in arena trials, and therefore achieve closer to maximal speeds. In lizards, intrinsically slower animals performed close to their maximum capacity in the field, whereas lizards with faster maximal capacities sprinted at a lower percentage of their maximum speed in the field [29]. Hence, when under strong selection (predator escape) in the field, species or individuals with lower physiological capacities compensate behaviourally and sprint closer to their maximum. Similar behavioural ‘locomotor compensation’ [29] may operate in mosquitofish that experience very strong selection (being eaten by a predator) and therefore sprint at greater speeds than the arena maximum, compared with bass that experience much weaker selection (missing out on a meal) and therefore sprint at a lower than maximal speed. Additionally, it is possible that maximal speeds of bass are not optimal for prey capture [14]. Laboratory measures of sprint speed are commonly used to assess animal performance under different experimental treatment and as a proxy measure for fitness [7,29]. The mismatch between arena measures and escape and attack speeds we observed means that caution has to be exercised when interpreting laboratory measures in an ecological context (see also [29]).

Predation pressure was lower in cold acclimation conditions. Time until first attack, duration of attacks and number of attacks may be interpreted as measures of predator motivation, and bass chronically exposed to low temperature showed lower motivation even at high test temperatures. Condition factors were similar in the two acclimation groups so that starvation did not play a role in determining motivation. The differences in motivation were induced by the chronic (acclimation) temperature differences rather than by the temperature of the predator at the time of the predation trials, because all measures of motivation were higher in the warm-acclimated group at all acute test temperatures.

The number of attacks, in particular, is associated with success of predators in catching prey, and its decline in cold-acclimated fish, regardless of the acute thermal conditions, would lead to a decline in predation pressure in winter, for example. Nonetheless, swimming performances acclimated well to cold temperatures, indicating that muscle function and the metabolic capacity to support swimming were maintained even though the motivation to catch prey, and probably food requirements, declined. The implications are that activity and daily metabolic requirements are also reduced at cooler temperatures, and that higher swimming performance may be ecologically important for predator escape rather than for catching prey, especially in juvenile bass. Similar responses occur in aestivating frogs, where metabolic rates are reduced during inactivity, but muscle mass is maintained, except at high temperatures (30°C [30]). Maintaining muscle mass and function is advantageous for aestivating frogs because it permits immediate emergence following rainfall. Avoidance of muscle disuse atrophy in aestivating frogs is thought to be facilitated by the reduction of reactive oxygen species resulting from lower metabolic rates [30].

Interestingly, even though predation pressure is higher under warm-acclimation conditions, the number of attacks made by bass declined at the test temperature (30°C) that exceeded acclimation temperature (25°C). At the same time, mosquitofish were significantly faster than bass at the high temperatures (25°C and 30°C). These data imply that under very warm conditions, predation pressures will decrease again. Specifically, for bass and mosquitofish, temperatures in freshwater bodies around Sydney could reach 30°C for brief periods in mid-summer but would be relatively rare currently (F. Seebacher 2011, unpublished data). However, elsewhere within the more northerly sympatric range of bass and mosquitofish (coastal areas from latitude 25°–39° S), and under future climate change, these temperatures will be more common. More generally, temperature influences predator–prey relationships [31–33], and similar differential acclimation responses that we report for bass and mosquitofish may be common for many interacting species.

Differential responses of species to thermal changes can have broader ecological implications [34,35]. Invasive species may benefit from warmer temperatures, particularly if their predators are unable to acclimate functional traits to a similar or greater extent. Our data indicate that at a population level, predation pressure on species such as mosquitofish will increase and then decrease as temperature rise. Warmer temperatures increase the metabolic demands of both predator and prey, and as temperatures increase beyond a critical point when predation success decreases, this could lead to a decline of predator populations as a result of starvation [36]. Thermal effects on predation pressure and capture success can modify community structure [37] by modulating trophic interactions [38,39]. In southeast Australia, mosquitofish compete with native fish [40] and predate on native larval anurans [41] so that reduced predation pressure on mosquitofish due to warmer temperatures can have negative implications for these aquatic communities.

We show that differential thermal responses at chronic and acute time scales affect species interactions, which suggests that this can be a mechanism by which global warming affects ecological communities. Most commonly, climate change is thought to influence species distribution and persistence by shifting environmental conditions beyond thermal tolerance ranges of individuals [42–44]. Importantly, we show that even within thermal tolerance ranges relatively modest thermal changes that do not cause mortality directly can have profound effects on the functioning of organisms and ecosystems.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by an Australian Research Council Discovery Grant to F.S. V.S.G. was supported by the International Postgraduate Research Scholarship from the Australian Department of Innovation, Industry, Science and Research. This work was approved by University of Sydney Animal Ethics Committee (approval no. L04/5-2010/2/5324) and by an NSW Industry and Investment Scientific Collection permit (permit no. P08/0028–2.0).

References

- 1.Huey R. B., Berrigan D., Gilchrist G. W., Herron J. C. 1999. Testing the adaptive significance of acclimation: a strong inference approach. Am. Zool. 39, 323–336 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson R. S., Franklin C. E. 2002. Testing the beneficial acclimation hypothesis. Trends Ecol. Evol. 17, 66–70 10.1016/S0169-5347(01)02384-9 (doi:10.1016/S0169-5347(01)02384-9) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seebacher F., Davison W., Lowe C. J., Franklin C. E. 2005. A falsification of the thermal specialization paradigm: compensation for elevated temperatures in Antarctic fishes. Biol. Lett. 1, 151–154 10.1098/rsbl.2004.0280 (doi:10.1098/rsbl.2004.0280) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Franklin C. E., Davison W., Seebacher F. 2007. Antarctic fish can compensate for rising temperatures: thermal acclimation of cardiac performance in Pagothenia borchgrevinki. J. Exp. Biol. 210, 3068–3074 10.1242/Jeb.003137 (doi:10.1242/Jeb.003137) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chown S. L., Gaston K. J., van Kleunen M., Clusella-Trullas S. 2010. Population responses within a landscape matrix: a macrophysiological approach to understanding climate change impacts. Evol. Ecol. 24, 601–616 10.1007/s10682-009-9329-x (doi:10.1007/s10682-009-9329-x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Domenici P., Claireaux G., McKenzie D. J. 2007. Environmental constraints upon locomotion and predator–prey interactions in aquatic organisms: an introduction. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 362, 1929–1936 10.1098/rstb.2007.2078 (doi:10.1098/rstb.2007.2078) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnston I. A., Temple G. K. 2002. Thermal plasticity of skeletal muscle phenotype in ectothermic vertebrates and its significance for locomotory behaviour. J. Exp. Biol. 205, 2305–2322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guderley H. 2004. Metabolic responses to low temperature in fish muscle. Biol. Rev. 79, 409–427 10.1017/S1464793103006328 (doi:10.1017/S1464793103006328) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stenseth N. C., Mysterud A., Ottersen G., Hurrell J. W., Chan K. S., Lima M. 2002. Ecological effects of climate fluctuations. Science 297, 1292–1296 10.1126/science.1071281297/5585/1292 (doi:10.1126/science.1071281297/5585/1292) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freitas V., Campos J., Fonds M., Van der Veer H. W. 2007. Potential impact of temperature change on epibenthic predator-bivalve prey interactions in temperate estuaries. J. Therm. Biol. 32, 328–340 10.1016/j.jtherbio.2007.04.004 (doi:10.1016/j.jtherbio.2007.04.004) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huey R. B., Kingsolver J. G. 1989. Evolution of thermal sensitivity of ectotherm performance. Trends Ecol. Evol. 4, 131–135 10.1016/0169-5347(89)90211-5 (doi:10.1016/0169-5347(89)90211-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Husak J. F., Fox S. F., Lovern M. B., Van Den Bussche R. A. 2006. Faster lizards sire more offspring: sexual selection on whole-animal performance. Evolution 60, 2122–2130 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watkins T. B. 1996. Predator-mediated selection on burst swimming performance in tadpoles of the Pacific tree frog, Pseudacris regilla. Physiol. Zool. 69, 154–167 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Domenici P., Blake R. W. 1997. The kinematics and performance of fish fast-start swimming. J. Exp. Biol. 200, 1165–1178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pyke G. H. 2008. Plague minnow or mosquito fish? A review of the biology and impacts of introduced Gambusia species. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 39, 171–191 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.39.110707.173451 (doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.39.110707.173451) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harris J. H. 1986. Reproduction of the Australian bass Macquaria novemaculeata (Perciformes: Percichthyidae) in the Sydney basin. Aust. J. Mar. Freshw. Res. 37, 209–235 10.1071/MF9860209 (doi:10.1071/MF9860209) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reid A. L., Seebacher F., Ward A. J. W. 2010. Learning to hunt: the role of experience in predator success. Behaviour 147, 223–233 10.1163/000579509x12512871386137 (doi:10.1163/000579509x12512871386137) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jain K. E., Birtwell I. K., Farrell A. P. 1998. Repeat swimming performance of mature sockeye salmon following a brief recovery period: a proposed measure of fish health and water quality. Can. J. Zool. 76, 1488–1496 10.1139/z98-079 (doi:10.1139/z98-079) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilson R. S., James R. S., Johnston I. A. 2000. Thermal acclimation of locomotor performance in tadpoles and adults of the aquatic frog Xenopus laevis. J. Comp. Physiol. B 170, 117–124 10.1007/s003600050266 (doi:10.1007/s003600050266) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sinclair E. L. E., Ward A. J. W., Seebacher F. 2011. Aggression-induced fin damage modulates trade-offs in burst and endurance swimming performance of mosquitofish. J. Zool. 283, 243–248 10.1111/j.1469-7998.2010.00776.x (doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2010.00776.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zaykin D. V., Zhivotovsky L. A., Westfall P. H., Weir B. S. 2002. Truncated product method for combining p-values. Genet. Epidemiol. 22, 170–185 10.1002/gepi.0042 (doi:10.1002/gepi.0042) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seebacher F., Wilson R. S. 2006. Fighting fit: thermal plasticity of metabolic function and fighting success in the crayfish Cherax destructor. Funct. Ecol. 20, 1045–1053 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2006.01194.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2435.2006.01194.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilson R. S., Hammill E., Johnston I. A. 2007. Competition moderates the benefits of thermal acclimation to reproductive performance in male eastern mosquitofish. Proc. R. Soc. B 274, 1199–1204 10.1098/rspb.2006.0401 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2006.0401) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnston I. A., Guderley H., Franklin C. E., Crockford T., Kamunde C. 1994. Are mitochondria subject to evolutionary temperature adaptation? J. Exp. Biol. 195, 293–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bremer K., Moyes C. D. 2011. Origins of variation in muscle cytochrome c oxidase activity within and between fish species. J. Exp. Biol. 214, 1888–1895 10.1242/Jeb.053330 (doi:10.1242/Jeb.053330) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gabriel W., Luttbeg B., Sih A., Tollrian R. 2005. Environmental tolerance, heterogeneity, and the evolution of reversible plastic responses. Am. Nat. 166, 339–353 10.1086/432558 (doi:10.1086/432558) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seebacher F. 2009. Responses to temperature variation: integration of thermoregulation and metabolism in vertebrates. J. Exp. Biol. 212, 2885–2891 10.1242/jeb.024430 (doi:10.1242/jeb.024430) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Irschick D. J., Losos J. B. 1998. A comparative analysis of the ecological significance of maximal locomotor performance in Caribbean anolis lizards. Evolution 52, 219–226 10.2307/2410937 (doi:10.2307/2410937) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Irschick D. J., Herrel A., Vanhooydonck B., Huyghe K., Van Damme R. 2005. Locomotor compensation creates a mismatch between laboratory and field estimates of escape speeds in lizards: a cautionary tale for performance to fitness studies. Evolution 59, 1579–1587 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Young K. M., Cramp R. L., White C. R., Franklin C. E. 2011. Influences of elevated temperature on metabolism during aestivation: implications for muscle disuse atrophy. J. Exp. Biol. 214, 3782–3789 10.1242/jeb.054148 (doi:10.1242/jeb.054148) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anderson M. T., Kiesecker J. M., Chivers D. P., Blaustein A. R. 2001. The direct and indirect effects of temperature on a predator–prey relationship. Can. J. Zool. 79, 1834–1841 10.1139/z01-158 (doi:10.1139/z01-158) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lass S., Spaak P. 2003. Temperature effects on chemical signalling in a predator–prey system. Freshwater Biol. 48, 669–677 10.1046/j.1365-2427.2003.01038.x (doi:10.1046/j.1365-2427.2003.01038.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kishi D., Murakami M., Nakano S., Maekawa K. 2005. Water temperature determines strength of top-down control in a stream food web. Freshwater Biol. 50, 1315–1322 10.1111/j.1365-2427.2005.01404.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2427.2005.01404.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Viergutz C., Kathol M., Norf H., Arndt H., Weitere M. 2007. Control of microbial communities by the macrofauna: a sensitive interaction in the context of extreme summer temperatures? Oecologia 151, 115–124 10.1007/s00442-006-0544-7 (doi:10.1007/s00442-006-0544-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baldridge A. K., Smith L. D. 2008. Temperature constraints on phenotypic plasticity explain biogeographic patterns in predator trophic morphology. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 365, 25–34 10.3354/Meps07485 (doi:10.3354/Meps07485) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abrahams M. V., Mangel M., Hedges K. 2007. Predator–prey interactions and changing environments: who benefits? Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 362, 2095–2104 10.1098/rstb.2007.2102 (doi:10.1098/rstb.2007.2102) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sanford E. 1999. Regulation of keystone predation by small changes in ocean temperature. Science 283, 2095–2097 10.1126/science.283.5410.2095 (doi:10.1126/science.283.5410.2095) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Platt T., Fuentes-Yaco C., Frank K. T. 2003. Spring algal bloom and larval fish survival. Nature 423, 398–399 10.1038/423398b (doi:10.1038/423398b) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Winder M., Schindler D. E. 2004. Climate change uncouples trophic interactions in an aquatic ecosystem. Ecology 85, 2100–2106 10.1890/04-0151 (doi:10.1890/04-0151) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arthington A. H., Marshall C. J. 1999. Diet of the exotic mosquitofish, Gambusia holbrooki, in an Australian lake and potential for competition with indigenous fish species. Asian Fish. Sci. 12, 1–16 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morgan L. A., Buttemer W. A. 1996. Predation by the non-native fish Gambusia holbrooki on small Litoria aurea and L. dentata tadpoles. Aust. Zool. 30, 143–149 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Parmesan C., Yohe G. 2003. A globally coherent fingerprint of climate change impacts across natural systems. Nature 421, 37–42 10.1038/Nature01286 (doi:10.1038/Nature01286) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thomas C. D., et al. 2004. Extinction risk from climate change. Nature 427, 145–148 10.1038/Nature02121 (doi:10.1038/Nature02121) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Terblanche J. S., Clusella-Trullas S., Deere J. A., Chown S. L. 2008. Thermal tolerance in a south-east African population of the tsetse fly Glossina pallidipes (Diptera, Glossinidae): implications for forecasting climate change impacts. J. Insect Physiol. 54, 114–127 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2007.08.007 (doi:10.1016/j.jinsphys.2007.08.007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]