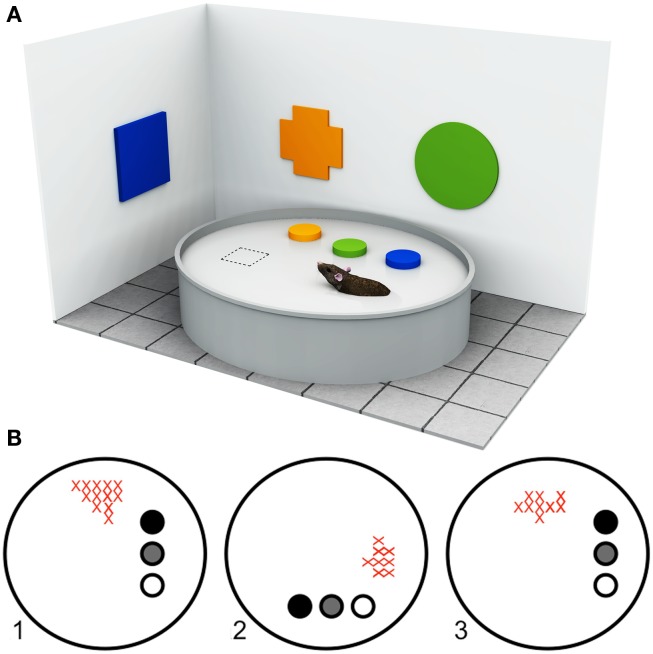

Figure 1.

Approaches to understanding landmark processing in rodents. (A) Example of a typical Morris Water Maze setup. The Morris Water Maze paradigm (Morris, 1981), originally developed for rodents, requires the animal to locate a hidden platform (dashed square) that is submerged below the surface of a large circular arena filled with opaque water, using available room cues (in this illustration, the colored geometric shapes). The start position is varied between trials so that animals cannot use proprioceptive or egocentric strategies, but must learn to use the configural relationships between objects within the room to locate the platform. By manipulating the available visual information, or by lesioning specific neural structures, it is possible to determine the types of cues and brain regions that are important for solving the task. (B) Firing rate maps of a hippocampal place cell adapted from Cressant et al. (1997). “Place cells” are spatially selective cells, found in the rodent hippocampus, that fire maximally when the rodent is within a well-defined region of the environment (i.e., within the cell’s “place field”) but not at any other location, independent of head and body direction. Place cell activity is thought to reflect a rodent’s internal spatial representation of the environment. As such, the navigational relevance of different types of environmental object can be inferred from the manner in which they influence place cell activity. The firing rates of a rodent hippocampal place cell within a circular arena are shown in the example. The filled circles represent three prominent objects within the arena. As the spatial locations of objects are rotated between trials (1–3), the place field of the place cell shifts accordingly (red crosses). In this example, the rodent’s internal spatial representation is anchored by the three objects.