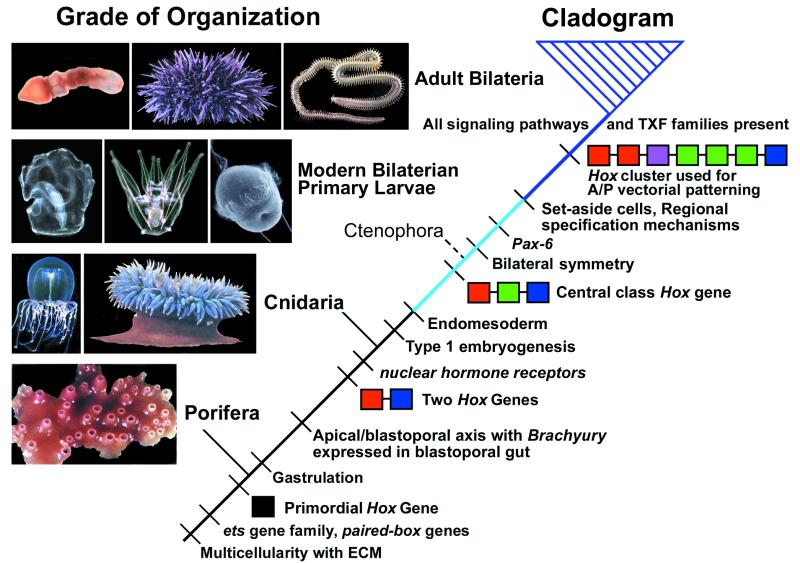

Figure 1.

A cladogram of basal metazoans and some of the important regulatory inventions leading to the crown group bilaterians (purple triangle). The dotted line leading to Ctenophora reflects the equivocal nature of evidence regarding their phylogenetic position. The change in grade of organization from a two-dimensional to a three-dimensional form required the evolution of endomesoderm. This stage is indicated by the light-blue line. With the evolution of set-aside cells and regional specification mechanisms, macroscopic bilaterian body plans are now evolvable, and this change is indicated by the purple line. By the time the crown group evolved, all signaling pathways and transcription factor (TXF) families had appeared. The single “primordial” Hox gene found in sponges is shown by the black box. Presumably this gene underwent tandem gene duplication resulting in two genes, an “anterior” gene related to Hox 1 and Hox 2 of bilaterians (shown in red) and a posterior gene related to Hox 9–13 (i.e., Abd-B relatives, shown in blue). A central class Hox gene has been found in ctenophores (Hox 4–8, shown in green). The latest common ancestor must have had at least seven Hox genes involving both gene duplications of previous classes (e.g., multiple anterior and middle genes) and new classes (Hox 3, violet box). This view of Hox cluster evolution devolves from studies of de Rosa et al. (33), Finnerty and Martindale (30), and others (see text). The adult enteropneust, the larval enteropneust, and the larval sea urchin photographs are from the authors' collections; the rest of the animal pictures are from ref. 40 [reproduced with permission from ref. 40 (Copyright 1980, Stanford University Press)].