Abstract

In this study we tried to confirm the effect of an astaxanthin-rich Haematococcus pluvialis extract on cognitive function in 96 subjects by a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled study. Healthy middle-aged and elderly subjects who complained of age-related forgetfulness were recruited. Ninety-six subjects were selected from the initial screen, and ingested a capsule containing astaxanthin-rich Haematococcus pluvialis extract, or a placebo capsule for 12 weeks. Somatometry, haematology, urine screens, and CogHealth and Groton Maze Learning Test were performed before and after every 4 weeks of administration. Changes in cognitive performance and the safety of astaxanthin-rich Haematococcus pluvialis extract administration were evaluated. CogHealth battery scores improved in the high-dosage group (12 mg astaxanthin/day) after 12 weeks. Groton Maze Learning Test scores improved earlier in the low-dosage (6 mg astaxanthin/day) and high-dosage groups than in the placebo group. The sample size, however, was small to show a significant difference in cognitive function between the astaxanthin-rich Haematococcus pluvialis extract and placebo groups. No adverse effect on the subjects was observed throughout this study. In conclusion, the results suggested that astaxanthin-rich Haematococcus pluvialis extract improves cognitive function in the healthy aged individuals.

Keywords: Astaxanthin, Haematococcus pluvialis, cognitive function, aging, clinical efficacy

Introduction

It is widely accepted that cognitive function decreases with aging. Moreover, dementia, Alzheimer disease, etc., are diseases in which cognitive function is drastically reduced.(1) Astaxanthin (Ax) is a carotenoid found in marine organisms such as shrimp, crab, krill, salmon, and microalgae.(2) It has strong anti-oxidant properties, as it consumes free radicals such as singlet oxygen to form stable triplet oxygen. In recent years, the effect of Ax against aging and against illnesses related to oxidisation stress has been confirmed by its use in cosmetics and whitening products and in the treatment of fatigue and cancer.(3,4) Ax exhibits immunomodulation properties;(5,6) alleviates eye fatigue;(7) and prevents Helicobacter pylori infection,(8) metabolic syndrome,(9) and atopic dermatitis.(10)

Due to its high consumption of glucose and oxygen, the brain tends to produce active oxygen and free radicals even though it is composed of substances that are easily oxidisable, such as unsaturated fatty acids and catecholamine. That is, the brain is an organ that is easily damaged by oxidisation stress. Brain health, such as that during normal aging and in neurodegenerative conditions such as Alzheimer disease or Parkinson disease, is closely related to oxidisation stress.(11,12) Halliwell reported oxidative damage in the aging brain, and suggested that anti-oxidants may play a role in protecting the brain from reactive oxygen species (ROS).(13)

Therefore, since Ax is a strong antioxidant, we anticipate that it will be beneficial for maintaining brain health. Ax improved cell survival and reduced apoptosis and caspase 3 and 9 activation in neuroblastoma cells exposed to oxidative stress. Ax also inhibits oxidation stress-induced apoptosis in nerve cells. Memory and learning ability, as assessed in the T-maze test, is improved in immature mice by treatment with Ax. Moreover, when a normal aging mouse was medicated with Ax, memory improvement was observed. In Morris water maze examinations in Fischer rats, Ax treatment improved the memory of both immature (4 months) and aged rats (18 months). The effect was more remarkable in the old rats than in the young ones, suggesting that Ax improves cognition and/or prevents age-related cognitive damage.

We performed a preliminary clinical trial of 12 weeks of astaxanthin-rich Haematococcus pluvialis extract (Ax-Hp) treatment in 10 healthy men between 50 to 69 years of age, who complaints of age-related forgetfulness to assess the effects of the supplements on cognition.(14) We reported changes in the P300 brain waves, related to cognitive function, and improvements in CogHealth scores.(14) This randomised double-blind placebo-controlled study was performed to validate the effects of Ax-Hp on cognitive function. In the preliminary trial, a 12-mg/day dose of Ax elicited an effect. In this trial, we employed a 12-mg/day dose and a 6-mg/day dose to look for the presence of a dose response.

Materials and Methods

Study subjects

Healthy men and women between 45 to 64 years of age, who complaints of age-related forgetfulness were recruited; 138 subjects participated after providing signed informed consent. The subjects’ height, body weight, body mass index (BMI), blood pressure, and pulse rate were measured, along with performing haematological and urinary analyses, the Hachinski Ischaemic Scale, and tests of cognitive function (Hasegawa Dementia Scale-Revised [HDS-R], CogHealth, and Groton Maze Learning Test [GMLT]).

Subjects were excluded if they exhibited signs of dementia (HDS-R score, ⩽20 points) or cerebrovascular dementia (Hachinski Ischaemic Score, ⩾7), habitually consumed Ax supplements, used games and books designed to improve cognitive function, or were judged unfit for participation due to the results of their laboratory analyses. Eventually, 96 subjects (46 men and 50 women, 55.7 ± 3.7 years of age) qualified for participation.

Study design

This randomised double-blind placebo-controlled study consisted of a high-dosage group (12 mg/day of Ax), low-dosage group (6 mg/day of Ax), and a placebo group. The subjects were randomly allocated into 3 groups (n = 32 per group). After confirming that the average age and BMI of each group were equivalent, the study coordinator named the 3 groups as the high-dosage group, low-dosage group, and placebo group, and created the allocation table. The coordinator also labelled the high-dosage, low-dosage, and placebo supplements with the subject IDs, according to the allocation table. The coordinator sealed and stored the allocation table until the study ended. The demographic characteristics of each group are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study subjects

| Characteristic | Placebo group |

Ax-Hp low-dosage group |

Ax-Hp high-dosage group |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | |

| No. of subjects | 32 | 32 | 32 |

| No. of men/women | 15/17 | 16/16 | 15/17 |

| Age (years) | 51.6 ± 5.3 | 51.1 ± 5.9 | 51.5 ± 5.7 |

| Height (cm) | 161.6 ± 7.0 | 161.8 ± 8.4 | 161.4 ± 8.9 |

| Body weight (kg) | 61.1 ± 10.1 | 61.0 ± 10.8 | 62.6 ± 11.6 |

| BMI | 23.3 ± 2.8 | 23.2 ± 2.9 | 23.9 ± 3.3 |

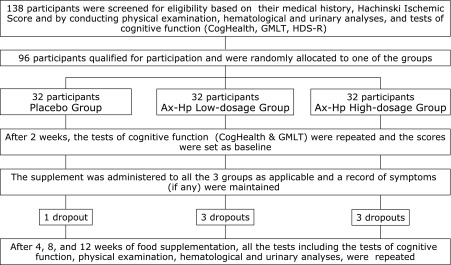

To minimise the learning effect, the CogHealth battery and GMLT were repeated 2 weeks after the screening tests; these scores were set as the baseline. Assessments of subjective symptoms, somatometry, haematological and urinary tests, and cognitive function tests (CogHealth and GMLT) were performed after 4, 8, and 12 weeks of Ax-Hp administration. The subjects maintained a diary to record their daily Ax-Hp supplement doses and the subjective symptoms during the 12-week study period (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the experimental design and procedure.

Supplements

Puresta® (YAMAHA Motor Co., Ltd.)(15) was used for Ax-rich Haematococcus pluvialis oil. The raw materials of the supplements were olive oil (K. Kobayashi & Co., Ltd.), gelatine (porcine in origin), Ax-Hp (6 or 12 mg of Ax dialcohol), glycerine, vitamin E, and an emulsifier. The placebo capsule had corn oil (J-OIL MILLS, Inc.) as a substitute for Ax-Hp. The subjects ingested the supplement after breakfast everyday for 12 weeks. When they could not take the supplement after breakfast, they were asked to take it after lunch or supper.

Ethics

The study protocol and informed consent documents were reviewed and approved by the ethics committee of Anti-Aging Science, Inc. All study subjects provided written informed consent prior to participation. The protocols were carried out under the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Cognitive function tests

CogHealth battery

The CogHealth battery measures response time and accuracy with 5 card games played on a personal computer. The card games include tests of ’simple reaction’, ’choice reaction’, ’working memory’, ’delayed recall’, and ’divided attention’. The ’simple reaction’ task requires the subjects to push a button as quickly as possible when the cards are placed face-up on a table. The ’choice reaction’ task requires subjects to identify whether a card is red or black by pushing a button (labelled YES or NO) when cards are placed face-up on a table. These tasks measure the reaction and control in a frontal lobe function. The ’working memory’ task requires subjects to identify whether a card is the same or different from the previous card. The ’delayed recall’ task requires subjects to identify whether overturned cards have appeared previously. These 2 tasks measure immediate memory and episodic memory. The ’divided attention’ task requires subjects to identify whether a card touches a line while moving up and down at random. This task measures spatial attention.

The response time is measured with a sensitivity of 1/1,000 s. The CogHealth battery is not influenced by culture, language, or level of education,(16) and is not influenced by the learning effect. Moreover, it can detect a slight change in cognitive function and can be used to diagnose mild cognitive impairment.(17,18)

The CogHealth battery is based on task switching as an evaluation of high-order cognitive functions (execution function), such as control of action or reconstruction of information processing.(19–21) Moreover, brain image analysis by fMRI has revealed frontal lobe activity associated with task switching; thus, the CogHealth test is also a frontal lobe function test.(22,23)

Reaction time in a task-switching test is a measure of the processing time in total cognition and performance processing, and is widely used as an index of cognitive information-processing ability.

Although CogHealth battery was developed in Australia, it has been validated in Japanese subjects.(24) A Japanese version of the CogHealth battery and the GMLT were offered with the cooperation of Health Solution, Inc. (Tokyo).

The subjects performed the CogHealth battery with a keypad that consists of only 2 keys to exclude the influence of computer skills. Prior to performing each task, the subjects received a full explanation of the task and were permitted to practice.

GMLT. The ’maze’ of the GMLT was specified at random on a personal computer in a 10 × 10 layout requiring 28 steps to move from the upper left to the lower right goal.(25) The subjects worked through the same hidden maze 5 times, and then performed 5 CogHealth tasks. The same maze was performed once again at the end of testing, to provide a measure of spatial working memory. The GMLT indicates a learning effect, while the CogHealth is not affected by learning.

In order to exclude the influence of computer skills, the subjects performed the test on a touch screen. The subjects received instructions for all tasks of CogHealth battery and GMLT, were asked to ’Please push a button quickly and correctly’, and were guided so that maximum performance might be demonstrated.(26)

Analysis of the results of CogHealth battery included mean response time (ms) for every task, mean accuracy (%) of ’working memory’ and ’delayed recall’, and those of the results of the GMLT included mean total duration (s) and total errors after performing a maze 6 times.

Somatometry

Somatometry data included height, body weight, BMI, blood pressure (systolic/diastolic), and pulse rate.

Haematological and urinary tests

Haematological parameters, including white blood cell count, red blood cell count, haemoglobin level, haematocrit, platelet count, MCV, MCH, and MCHC; biochemical parameters, including levels of total protein, albumin, total bilirubin, triglycerides, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, BUN, creatinine, AST, ALT, γ-GTP, LDH, ALP, uric acid, serum electrolytes (Na, K, and Cl), and fasting blood sugar and A/G ratio; and qualitative urinalysis parameters, including protein, glucose, occult blood, pH, and urobilinogen, were determined.

Statistical analysis

All cognitive parameters of CogHealth and GMLT were compared between groups with 2-way factorial ANOVA adjusted for age and sex. One-way repeated measure ANOVA, adjusted for age and sex, was used to compare scores at baseline and at after 4, 8, and 12 weeks; multiple comparisons were performed using Bonferroni correction.

All statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 16.0J for Windows (SPSS Japan Inc., Tokyo, Japan).

Results

The effectiveness and safety of Ax-Hp were evaluated in 89 subjects who participated in all tests (high-dosage group, 29; low-dosage group, 29; and placebo, 31). The subjects ingested 80% or more of the provided Ax-Hp supplements.

Improvement of CogHealth score

Table 2 shows the comparison of 3 groups at the time of Ax-Hp administration, and Table 3 shows the mean response time of all 5 CogHealth tasks and the mean accuracy of 2 tasks—’working memory’ and ’delayed recall’—at baseline and at 4, 8, and 12 weeks of Ax-Hp administration. The 3 groups did not significantly differ. However, the changes in response time were as follows: in the high-dosage group, improvement trends were observed for ’choice reaction’ (451.1 ± 56.7 vs 480.1 ± 77.5), ’delayed recall’ (818.3 ± 195.9 vs 880.1 ± 189.4), and ’divided attention’ (385.3 ± 72.5 vs 419.4 ± 79.6), each p values <0.1 at 12 weeks, and ’working memory’ was significantly improved (609.2 ± 123.5 vs 655.9 ± 136.5; p<0.05) at 12 weeks; improvement trends were observed for ’working memory’ (644.6 ± 124.7 vs 686.0 ± 148.9; p<0.1) at 12 weeks in the placebo group and ’delayed recall’ (844.4 ± 103.8 vs 912.2 ± 145.6; p<0.1) at 8 weeks in the low-dosage group. ’Delayed recall’, a measure of accuracy, significantly improved in the high-dosage group at 12 weeks (72.9 ± 7.5 vs 67.3 ± 11.8; p<0.05). The results of the CogHealth test suggest that 12 weeks of high-dose Ax-Hp administration improved cognitive function.

Table 2.

Comparison of the 3 groups of CogHealth at the time of Ax-Hp administration

| Task |

p value |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Time | Group | Interaction | |

| Response time | |||

| Simple reaction | 0.376 | 0.249 | 0.817 |

| Choice reaction | 0.601 | 0.770 | 0.826 |

| Working memory | 0.220 | 0.636 | 0.436 |

| Delayed recall | 0.174 | 0.552 | 0.423 |

| Divided attention | 0.621 | 0.467 | 0.810 |

| Accuracy | |||

| Working memory | 0.074 | 0.892 | 0.178 |

| Delayed recall | 0.343 | 0.344 | 0.635 |

Dropouts were excluded from the data analysis. Data were analyzed by 2-way factorial ANOVA adjusted for age and sex.

Table 3.

Mean response times and accuracies (±SD) on CogHealth tasks at baseline, and after 4, 8, and 12 weeks of Ax treatment

| Group/Task | Baseline |

4 weeks |

8 weeks |

12 weeks |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | p (vs baseline) | Mean ± SD | p (vs baseline) | Mean ± SD | p (vs baseline) | |

| Placebo group (n = 31) | |||||||

| Response time (ms) | |||||||

| Simple reaction | 288.7 ± 59.1 | 271.5 ± 38.2 | 0.789 | 267.8 ± 40.6 | 0.345 | 265.0 ± 36.9 | 0.123 |

| Choice reaction | 467.5 ± 70.9 | 446.4 ± 53.1 | 0.506 | 453.1 ± 56.5 | 1.000 | 440.9 ± 52.8 | 0.124 |

| Working memory | 686.0 ± 148.9 | 647.7 ± 100.4 | 0.194 | 670.6 ± 151.5 | 1.000 | 644.6 ± 124.7 | 0.071† |

| Delayed recall | 909.7 ± 218.1 | 875.3 ± 217.8 | 1.000 | 887.8 ± 243.1 | 1.000 | 903.8 ± 270.1 | 1.000 |

| Divided attention | 413.0 ± 103.3 | 390.0 ± 75.2 | 0.597 | 379.6 ± 82.0 | 0.153 | 388.7 ± 73.9 | 0.397 |

| Accuracy (%) | |||||||

| Working memory | 95.1 ± 5.3 | 96.2 ± 3.8 | 1.000 | 95.2 ± 5.5 | 1.000 | 94.9 ± 8.3 | 1.000 |

| Delayed recall | 66.9 ± 10.3 | 68.8 ± 8.6 | 1.000 | 71.1 ± 10.4 | 0.355 | 69.2 ± 9.4 | 1.000 |

| AX low-dosage group (n = 29) | |||||||

| Response time (ms) | |||||||

| Simple reaction | 303.4 ± 81.7 | 284.3 ± 46.2 | 0.660 | 274.8 ± 39.4 | 0.077 | 285.0 ± 48.0 | 0.608 |

| Choice reaction | 468.0 ± 82.6 | 448.8 ± 60.4 | 0.558 | 440.2 ± 52.9 | 0.080 | 446.7 ± 44.0 | 0.393 |

| Working memory | 661.9 ± 120.2 | 651.4 ± 94.2 | 1.000 | 629.6 ± 96.4 | 0.352 | 641.6 ± 91.8 | 1.000 |

| Delayed recall | 912.2 ± 145.6 | 882.3 ± 139.5 | 1.000 | 844.4 ± 103.8 | 0.051† | 878.4 ± 131.4 | 1.000 |

| Divided attention | 428.8 ± 72.4 | 411.9 ± 85.7 | 1.000 | 406.7 ± 71.9 | 0.960 | 405.3 ± 81.6 | 0.483 |

| Accuracy (%) | |||||||

| Working memory | 94.1 ± 5.0 | 95.3 ± 4.4 | 1.000 | 96.4 ± 5.3 | 0.159 | 96.7 ± 3.7 | 0.186 |

| Delayed recall | 70.7 ± 6.7 | 72.4 ± 11.0 | 1.000 | 72.9 ± 8.8 | 1.000 | 71.0 ± 7.9 | 1.000 |

| AX high-dosage group (n = 29) | |||||||

| Response time (ms) | |||||||

| Simple reaction | 302.9 ± 71.2 | 292.2 ± 49.7 | 1.000 | 284.5 ± 56.7 | 0.626 | 280.6 ± 47.3 | 0.242 |

| Choice reaction | 480.1 ± 77.5 | 454.7 ± 64.1 | 0.207 | 453.1 ± 67.2 | 0.104 | 451.1 ± 56.7 | 0.083† |

| Working memory | 655.9 ± 136.5 | 638.6 ± 130.2 | 1.000 | 624.5 ± 132.1 | 0.319 | 609.2 ± 123.5 | 0.044* |

| Delayed recall | 880.1 ± 189.4 | 843.9 ± 182.8 | 0.852 | 829.4 ± 209.8 | 0.302 | 818.3 ± 195.9 | 0.097† |

| Divided attention | 419.4 ± 79.6 | 415.4 ± 104.9 | 1.000 | 392.3 ± 86.9 | 0.483 | 385.3 ± 72.5 | 0.074† |

| Accuracy (%) | |||||||

| Working memory | 95.4 ± 5.8 | 93.8 ± 6.6 | 0.433 | 95.4 ± 5.5 | 1.000 | 95.6 ± 7.4 | 1.000 |

| Delayed recall | 67.3 ± 11.8 | 71.3 ± 9.0 | 0.361 | 71.5 ± 7.3 | 0.320 | 72.9 ± 7.5 | 0.028* |

Dropouts were excluded from the data analysys. †p<0.1, *p<0.05, **p<0.01 (vs baseline). Data were analyzed by one-way repeated measure ANOVA, adjusted for age and sex. Multiple comparisons of 4, 8, and 12 weeks with baseline were performed using Bonferroni correction.

Improvement of GMLT score

Table 4 shows the comparison of 3 groups at the time of Ax-Hp administration, and Table 5 shows the total durations and errors of the 6 trials of GMLT at baseline and at 4, 8, and 12 weeks of Ax-Hp administration. There was no significant difference in the 3 groups. In each group, the total duration was significantly shortened at 8 weeks, but there was no difference between the groups.

Table 4.

Comparison of the 3 groups of GMLT at the time of Ax-Hp administration

| Task |

p value |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Time | Group | Interaction | |

| Total duration | 0.185 | 0.850 | 0.870 |

| Total errors | 0.724 | 0.905 | 0.278 |

Dropouts were excluded from the data analysys. Data were analyzed by 2-way factorial ANOVA adjusted for age and sex.

Table 5.

Mean total duration and total errors (±SD) on GMLT tasks at baseline, and after 4, 8, and 12 weeks of Ax treatment

| Group/Task | Baseline |

4 weeks |

8 weeks |

12 weeks |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | p (vs baseline) | Mean ± SD | p (vs baseline) | Mean ± SD | p (vs baseline) | |

| Placebo group (n = 31) | |||||||

| Total duration (s) | 158.8 ± 36.0 | 148.7 ± 35.6 | 0.193 | 143.0 ± 34.9 | 0.017* | 134.4 ± 33.2 | <0.001** |

| Total errors | 74.3 ± 22.9 | 67.8 ± 23.3 | 0.925 | 65.1 ± 23.0 | 0.258 | 60.7 ± 25.6 | 0.003** |

| Ax low-dosage group (n = 29) | |||||||

| Total duration (s) | 157.8 ± 25.9 | 147.3 ± 21.5 | 0.322 | 137.2 ± 23.8 | 0.002** | 127.8 ± 16.2 | <0.001** |

| Total errors | 79.9 ± 31.0 | 63.3 ± 24.5 | 0.005** | 61.3 ± 21.6 | 0.001** | 57.3 ± 20.7 | <0.001** |

| Ax high-dosage group (n = 29) | |||||||

| Total duration (s) | 162.0 ± 44.8 | 153.2 ± 43.0 | 0.517 | 139.5 ± 34.3 | <0.001** | 135.4 ± 33.2 | <0.001** |

| Total errors | 83.0 ± 36.9 | 68.9 ± 33.9 | 0.024* | 60.8 ± 24.5 | <0.001** | 60.6 ± 25.1 | <0.001** |

Dropouts were excluded from the data analysys. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 (vs baseline). Data were analyzed by one-way repeated measure ANOVA, adjusted for age and sex. Multiple comparisons of 4, 8, and 12 weeks with baseline were performed using Bonferroni correction.

However, the total errors in each group were as follows: the low-dose group showed significant improvement after 4 weeks (63.3 ± 24.5 at Week 4, 61.3 ± 21.6 at Week 8, and 57.3 ± 20.7 at Week 12, each p<0.01 vs baseline; 79.9 ± 31.0); the high-dose group also showed significant improvement after 4 weeks (68.9 ± 33.9; p<0.05 at Week 4, and 60.8 ± 24.5; p<0.01 at Week 8 and 60.6 ± 25.1; p<0.01 at Week 12, each p values vs baseline; 83.0 ± 36.9), whereas the placebo group showed significant improvement at 12 weeks (60.7 ± 25.6 vs 74.3 ± 22.9, p<0.01).

On the basis of these results, we conclude that short-term spatial working memory was improved by ingestion of 6 mg of Ax.

Safety evaluation of Ax-Hp

Somatometry, haematological and urinary tests, and an oral consultation after 12 weeks of Ax-Hp administration revealed no confirmed adverse effects, indicating that Ax-Hp supplementation is safe.

Discussion

There have been many reports of research on cognitive functional improvement in the fields of medicine, psychology, and exercise physiology. The aging population and the medical issues that accompany aging have raised concerns about cognitive function improvement. And it is hoped that prevention may be achieved via specific dietary changes; there have been promising reports on the effectiveness of docosahexaenoic acid,(27) arachidonic acid,(28) Ginkgo biloba,(29) Pinus radiata bark extract,(30) and acetic acid bacteria(31) in retarding cognitive function loss.

Ax is a strong anti-oxidant. Nakagawa et al.(32) reported the anti-oxidant effect of Ax-Hp on phospholipid peroxidation in human erythrocytes. Iwabayashi et al.(33) reported that Ax-Hp increases the biological anti-oxidants potential (BAP) in human. It is clear that the anti-oxidant activity of Ax-Hp is effective in human and animal studies. This study lets expect that Ax-Hp reduces oxidisation in the brain, leading to improved scores in tests of cognitive function.

Flavonoids are strong natural anti-oxidants like Ax, and they were thought to improve age-related cognitive decline. Youdim et al.(34) reported on the neuroprotective effects of dietary flavonoids in vivo. Pipingas et al.(30) reported that flavonoid-rich P. radiata bark extract improved cognitive function in tests of immediate recognition and spatial working memory. It is thought that the brain and nervous oxidisation are improved by the anti-oxidant activity of flavonoids, as is the case with Ax-Hp.

We performed a preliminary clinical trial of Ax-Hp and cognitive function improvement in 10 healthy men between 50 to 69 years of age, who complained of age-related forgetfulness. We reported that the response time of 5 CogHealth tasks was significantly improved (p<0.05) and that the amplitude of P300 brain waves, which are related to cognitive function, tended to increase (p<0.1) after 12 weeks of Ax-Hp treatment.

This randomised double-blind placebo-controlled study was performed to validate the beneficial effects of Ax-Hp on cognitive function in human subjects. Based on the results of the preliminary study, the high dosage was set at 12 mg/day, and 6 mg/day was set as the low dosage in order to confirm the presence of a dose response. The administration period was set to 12 weeks as in the preliminary study. Brain function was assessed with the CogHealth test and GMLT, both of which can perform objective measures in a large number of subjects.

We failed to show a significant difference between groups in the CogHealth test. No differences were observed at any of the assessments (4, 8, or 12 weeks). In addition, there were no differences between the high-dosage, low-dosage, and placebo groups in the reaction time and accuracy of the task-switching test. However, we observed significant improvements in the high-dose group in the response time for 1 task and in the accuracy of 1 task, and improvement trends was observed in 3 tasks. We conclude that these significant differences and trends are indicative of the Ax-induced improvement in cognitive function.

GMLT also revealed no significant differences between groups. The total duration did not change between groups or over time. However, total error improved significantly by 4 weeks in the low-dosage and high-dosage groups in contrast to the placebo group, which showed significant improvement only at 12 weeks. These results also suggest the Ax-induced improvement in cognitive function.

Although improvements in the CogHealth test were observed only with a dose of 12 mg/day, GMLT scores were improved at 6 mg/day. This difference may be because the methods of measuring cognitive performance differ. The GMLT includes a test of spatial working memory that is highly sensitive, can be used to measure age-related reductions in cognitive function, and can detect the effect of a supplement or remedy. Further verification is required.

Although the tests employed by Pipingas et al.(30) differ from the tests used in this study, immediate recognition is evaluated by the CogHealth test and spatial working memory is evaluated by the GMLT. The combination of these tasks may be useful to verify other supplements or remedies.

The CogHealth test revealed improvements in cognitive function with 12 mg/day Ax-Hp for 12 weeks. This supports the results of our preliminary clinical study. In particular, the improvement in response time, which is a measure of short-term memory, and in the accuracy of the ’delayed recall’ task was remarkable. Moreover, total errors in the GMLT, which is also associated with memory, showed significant improvement with 6 and 12 mg/day Ax-Hp.

However, significant differences between groups were not observed, possibly due to the small sample size. Moreover, the average age may have been too young to observe age-related cognitive decline. We plan to investigate this issue further.

We observed no adverse effects to express any concerns regarding the safety of Ax-Hp.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Y. Koga (Department of Neuropsychiatry, Kyorin University School of medicine) for planning the study design; R. Sakurai (Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Gerontology) for data analysis.

Conflicts of Interests

This work was supported by a grant from Yamaha Motor Co., Ltd.

References

- 1.Savla GN, Palmer BW. Neuropsychology in Alzheimer’s disease and other dementia research. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2005;18:621–627. doi: 10.1097/01.yco.0000184413.36706.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hussein G, Sankawa U, Goto H, Matsumoto K, Watanabe H. Astaxanthin, a carotenoid with potential in human health and nutrition. J Nat Prod. 2006;69:443–449. doi: 10.1021/np050354+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kurihara H, Koda H, Asami S, Kiso Y, Tanaka T. Contribution of the antioxidative property of astaxanthin to its protective effect on the promotion of cancer metastasis in mice treated with restraint stress. Life Sci. 2002;70:2509–2520. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(02)01522-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tanaka T, Kawamori T, Ohnishi M, et al. Suppression of azoxymethane-induced rat colon carcinogenesis by dietary administration of naturally occurring xanthophylls astaxanthin and canthaxanthin during the postinitiation phase. Carcinogenesis. 1995;16:2957–2963. doi: 10.1093/carcin/16.12.2957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jyonouchi H, Sun S, Mizokami M, Gross MD. Effects of various carotenoids on cloned, effector-stage T-helper cell activity. Nutr Cancer. 1996;26:313–324. doi: 10.1080/01635589609514487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mahmoud FF, Haines DD, Abul HT, Abal AT, Onadeko BO, Wise JA. In vitro effects of astaxanthin combined with ginkgolide B on T lymphocyte activation in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from asthmatic subjects. J Pharmacol Sci. 2004;94:129–136. doi: 10.1254/jphs.94.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nagaki Y, Hayasaka S, Yamada T, Hayasaka Y, Sanada M, Uonomi T. Effects of astaxanthin on accommodation, critical flicker fusion, and pattern visual evoked potential in visual display terminal workers. J Trad Med. 2002;19:170–173. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang X, Willén R, Wadström T. Astaxanthin-rich algal meal and vitamin C inhibit Helicobacter pylori infection in BALB/cA mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:2452–2457. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.9.2452-2457.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uchiyama A, Okada Y. Clinical efficacy of astaxanthin-containing Haematococcus pluvialis extract for volunteers at-risk of metabolic syndrome. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2008;43:38–43. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Satoh A, Kawamura T, Horibe T, et al. Effect of the intake of astaxanthin-containing Haematococcus pluvialis extract on the severity, immunofunction and physiological function in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Environ Dermatol Cutan Allergol. 2009;3:429–438. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mattson MP, Chan SL, Duan W. Modification of brain aging and neurodegenerative disorders by genes, diet, and behavior. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:637–672. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00004.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schon EA, Manfredi G. Neuronal degeneration and mitochondrial dysfunction. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:303–312. doi: 10.1172/JCI17741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Halliwell B. Role of free radicals in the neurodegenerative diseases: therapeutic implications for antioxidant treatment. Drugs Aging. 2001;18:685–716. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200118090-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Satoh A, Tsuji S, Okada Y, et al. Preliminary clinical evaluation of toxicity and efficacy of a new astaxanthin-rich Haematococcus pluvialis extract. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2009;44:280–284. doi: 10.3164/jcbn.08-238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Satoh A, Ishikura M, Murakami N, Zhang K, Sasaki D. The innovation of technology for microalgae cultivation and its application in functional foods and the nutraceutical industry. In: Bagchi D, Lau FC, Ghosh DK, editors. Biotechnology in Functional Foods and Nutraceuticals. London: Taylor & Francis Group, CRC Press; 2010. pp. 313–329. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cairney S, Clough AR, Maruff P, Collie A, Currie BJ, Currie J. Saccade and cognitive function in chronic kava users. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:389–396. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Darby D, Maruff P, Collie A, McStephen M. Mild cognitive impairment can be detected by multiple assessments in a single day. Neurology. 2002;59:1042–1046. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.7.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cho A, Sugimura M, Nakano S. Detection of mild cognitive impairment by CogHealth. Jpn J Geriatric Psychiatry. 2006;17:210–217. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cepeda NJ, Kramer AF, Gonzalez de Sather JC. Changes in executive control across the life span: examination of task-switching performance. Dev Psychol. 2001;37:715–730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hsieh S, Liu LC. The nature of switch cost: task set configuration or carry-over effect? Brain Res Cogn Brain Res. 2005;22:165–175. doi: 10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kramer AF, Hahn S, Cohen NJ, et al. Ageing, fitness and neurocognitive function. Nature. 1999;400:418–419. doi: 10.1038/22682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dove A, Pollmann S, Schubert T, Wiggins CJ, von Cramon DY. Prefrontal cortex activation in task switching: an event-related fMRI study. Brain Res Cogn Brain Res. 2000;9:103–109. doi: 10.1016/s0926-6410(99)00029-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kimberg DY, Aguirre GK, D’Esposito M. Modulation of task-related neural activity in task-switching: an fMRI study. Brain Res Cogn Brain Res. 2000;10:189–196. doi: 10.1016/s0926-6410(00)00016-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ogata S, Yamada T, Motohashi N. Evaluation of reliability, validity and transportability of CogHealth. Jpn J of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2008;10:119–120. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pietrzak RH, Maruff P, Snyder PJ. Convergent validity and effect of instruction modification on the Groton maze learning test: a new measure of spatial working memory and error monitoring. Int J Neurosci. 2009;119:1137–1149. doi: 10.1080/00207450902841269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Woodworth RS. Experimental psychology. New York: Holt; 1938. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hamazaki T, Thienprasert A, Kheovichai K, Samuhaseneetoo S, Nagasawa T, Watanabe S. The effect of docosahexaenoic acid on aggression in elderly Thai subjects—a placebo-controlled double-blind study. Nutr Neurosci. 2002;5:37–41. doi: 10.1080/10284150290007119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kotani S, Sakaguchi E, Warashina S, et al. Dietary supplementation of arachidonic and docosahexaenoic acids improves cognitive dysfunction. Neurosci Res. 2006;56:159–164. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kennedy DO, Scholey AB, Wesnes KA. The dose-dependent cognitive effects of acute administration of Ginkgo biloba to healthy young volunteers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2000;151:416–423. doi: 10.1007/s002130000501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pipingas A, Silberstein RB, Vitetta L, et al. Improved cognitive performance after dietary supplementation with a Pinus radiata bark extract formulation. Phytother Res. 2008;22:1168–1174. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fukami H, Tachimoto H, Kishi M, et al. Continuous ingestion of acetic acid bacteria: effect on cognitive function in healthy middle-aged and elderly persons. Anti-Aging Medicine. 2009;6:60–65. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakagawa K, Kiko T, Miyazawa T, et al. Antioxidant effect of astaxanthin on phospholipid peroxidation in human erythrocytes. Br J Nutr. 2011;105:1563–1571. doi: 10.1017/S0007114510005398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Iwabayashi M, Fujioka N, Nomoto K, et al. Efficacy and safety of eight-week treatment with astaxanthin in individuals screened for increased oxidative stress burden. Anti-Aging Medicine. 2009;6:15–21. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Youdim KA, Spencer JP, Schroeter H, Rice-Evans C. Dietary flavonoids as potential neuroprotectants. Biol Chem. 2002;383:503–519. doi: 10.1515/BC.2002.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]