Summary

Cell fusion plays a well-recognized, physiological role during development. Bone-marrow-derived hematopoietic cells have been shown to fuse with non-hematopoietic cells in a wide variety of tissues. Some organs appear to resolve the changes in ploidy status, generating functional and mitotically-competent events. However, cell fusion exclusively involving hematopoietic cells has not been reported. Indeed, genomic copy number variation in highly replicative hematopoietic cells is widely considered a hallmark of malignant transformation. Here we show that cell fusion occurs between cells of the hematopoietic system under injury as well as non-injury conditions. Experiments reveal the acquisition of genetic markers in fusion products, their tractable maintenance during hematopoietic differentiation and long-term persistence after serial transplantation. Fusion events were identified in clonogenic progenitors as well as differentiated myeloid and lymphoid cells. These observations provide a new experimental model for the study of non-pathogenic somatic diversity in the hematopoietic system.

Key words: Copy number variation, Intra-hematopoietic cell fusion, Somatic diversity

Introduction

Non-pathogenic genetic variation and genome-wide copy number variation (CNV) have been demonstrated in somatic tissues of several organisms, including humans, fruit flies and yeast (Conrad et al., 2010; Hastings et al., 2009; Torres et al., 2010). Mechanisms proposed for the generation of CNV implicate cell-intrinsic means of DNA recombination (Zhang et al., 2009). Polyploid progeny of murine hepatocytes undergo ploidy reduction, propagate CNV, and generate genetically diverse events (Duncan et al., 2010). However, a recent study also demonstrates cell fusion between bone-marrow-derived cells (BMDCs) and hepatocytes, suggesting that CNV is generated by merging DNA from two separate cells rather than from recombination events within a single cell (Duncan et al., 2009).

Bone-marrow-derived cells can fuse with hepatocytes, neurons or epithelial cells of the intestine, respectively, in a process that is seemingly amplified by acute tissue damage or inflammation (Bailey et al., 2006; Davies et al., 2009; Johansson et al., 2008; Nygren et al., 2008; Rizvi et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2003; Willenbring et al., 2004). Such products of ‘heterotypic’ cell fusion have been found to acquire functional characteristics of the host tissue and are considered evidence for a physiological regenerative mechanism (Palermo et al., 2009). Other than in the liver, direct tracking of genetic markers in fusion events and serial evaluation of mitotic competence and cell fate have not been extensively performed. This probably reflects the experimental focus of previous studies, technical limitations or the post-mitotic nature of specific fusion partner cell types (e.g. neurons). Aside from rare reports of incidentally detected somatic mosaicism, changes in genomic copy number the hematopoietic system are generally associated with malignant transformation (Piotrowski et al., 2008).

Congenic mice harboring polymorphisms at the Ly5 locus expressing distinct (CD45.1, CD45.2) cell surface markers are frequently used to dissect donor–host contributions for the study of hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) function and cell–cell fusion (McCulloch and Till, 1960; Zebedee et al., 1991). Co-expression of both CD45 donor and host isotype cell surface markers after ablative transplantation is widely attributed to experimental artifact, or considered evidence of membrane protein transfer between hematopoietic cells (Cho and Hill, 2008; Yamanaka et al., 2009). Here, we carefully dissect events with parental marker co-expression and present evidence of hematopoietic ‘homotypic’ cell fusion (i.e. fusion between cells arising in the same tissue) and marker CNV by interphase FISH and SNP-PCR. We observe homotypic hematopoietic fusion at comparable rates under non-injury conditions in a parabiosis model and show that intra-hematopoietic cell fusion produces mitotically competent, clonogenic progenitors that are genotypically diverse for unique informative markers without evidence of malignant transformation.

Results and Discussion

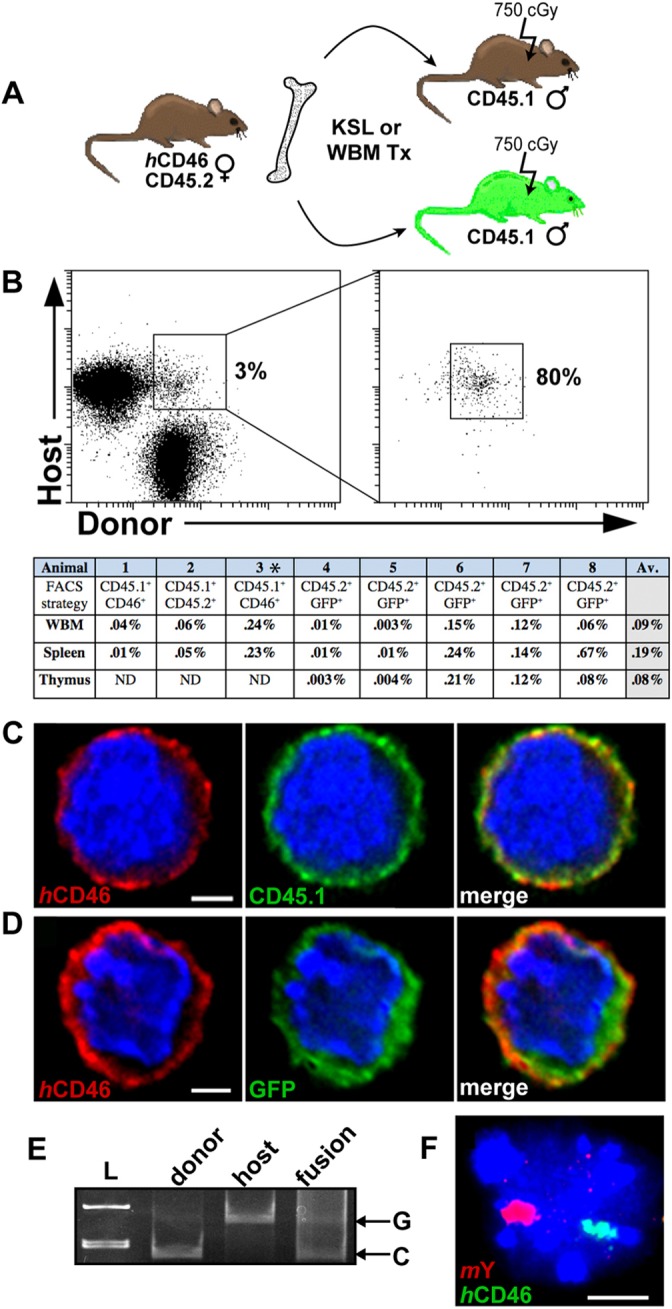

Intra-hematopoietic cell fusion events isolated from irradiated transplant animals

We hypothesized that cell fusion could be a potential mechanism for generating genetic diversity within hematopoietic tissues and sought to identify intra-hematopoietic cell fusion progeny (Anderson et al., 2011; Chandhok and Pellman, 2009). In independent experiments, sublethally irradiated male recipients (CD45.1) received either congenic, CD45 (Ly5)-mismatched c-kit+, sca-1+, Lin− (KSL) cells, or unfractionated bone marrow cells from female donors (CD45.2) transgenic (hemizygous) for human CD46 (Fig. 1A) (Yannoutsos et al., 1996). In an additional model, sublethally irradiated CD45.1 GFP+ males received whole bone marrow from CD45.2 females transgenic for human CD46 (Fig. 1A). Following hematopoietic reconstitution of recipients with multi-lineage donor chimerism (40–90%) in the peripheral blood, the hematopoietic tissues were harvested for analysis at time points between 1 and 12 months after transplantation. Cells co-expressing human CD46 (donor) and either CD45.1 cell surface antigen or GFP (both host) were serially sorted for improved stringency (Fig. 1B). A ‘doublet discriminator’ was used to exclude isolation of ‘doublets’ (i.e. two attached cells) (Hughes et al., 2009; Wersto et al., 2001). We observed cells co-expressing parental markers in all donor–host combinations and following different FACS sorting strategies (Fig. 1B). Shared marker expression in individual, sorted cells was confirmed by immunofluorescent (IF) deconvolution microscopy and z-stack analysis (Fig. 1C,D), distinguishing cells co-expressing donor–host markers from doublets. To exclude ambiguity from surface antigen or membrane transfer between donor and host hematopoietic cells (Yamanaka et al., 2009), DNA evidence of fusion was demonstrated by single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) typing (D1Mit421.1) for CD45.1 and CD45.2 alleles. Genomic DNA from flow-cytometrically isolated single CD45.1+ CD46+ cells revealed amplification of both donor and host SNPs (Fig. 1E), whereas cells sorted from control animals demonstrated only their predicted unique donor or host CD45 SNP signature (supplementary material Fig. S1). Validation of cell fusion within the sorted population was further corroborated by interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis (Fig. 1F) showing synkarya containing genetic markers of both donor (human CD46) and host (mouse Y chromosome) origin. These observations suggest the acquisition and expression of genetic markers through fusion between hematopoietic cells and illustrate their long-term persistence.

Fig. 1.

Hematopoietic cell fusion following host radiation injury. (A) Transplantation strategy. (B) FACS plots of cells isolated from transplant recipients following serial sort for co-expression of CD45.1+ (host) and human CD46+ (donor). Animal 3* received KSL, all other animals in the table received whole bone marrow. The frequency of co-expressing events recovered following serial sorting was adjusted for sort purity and is recorded in the table. (C) Images of one z-plane of a human CD46+ CD45.1+ sorted whole bone marrow cell or (D) sorted CD45.2+ GFP+ spleen cell. Cytospun cells were stained with antibodies against donor (human CD46–PE, red), and host markers (C, CD45.1–APC, green, or D, anti-GFP Alexa Fluor 488, green) and DAPI (blue), and visualized with deconvolution fluorescent microscopy. Scale bars: 2 µm. (E) Single-cell SNP-PCR on a fused CD45.2+ GFP+ sorted thymus cell of a CD45.1–GFP transplant recipient, shown with controls for each allele. A Beizer correction was applied to Fig. 1E in its entirety to reduce appearance of background smearing; linear adjustments to intensity were applied to all subsequent gel images. L, ladder. (F) Interphase FISH analysis of a fused cell that contains mouse Y (red) and human CD46 (green). Scale bar: 5 µm.

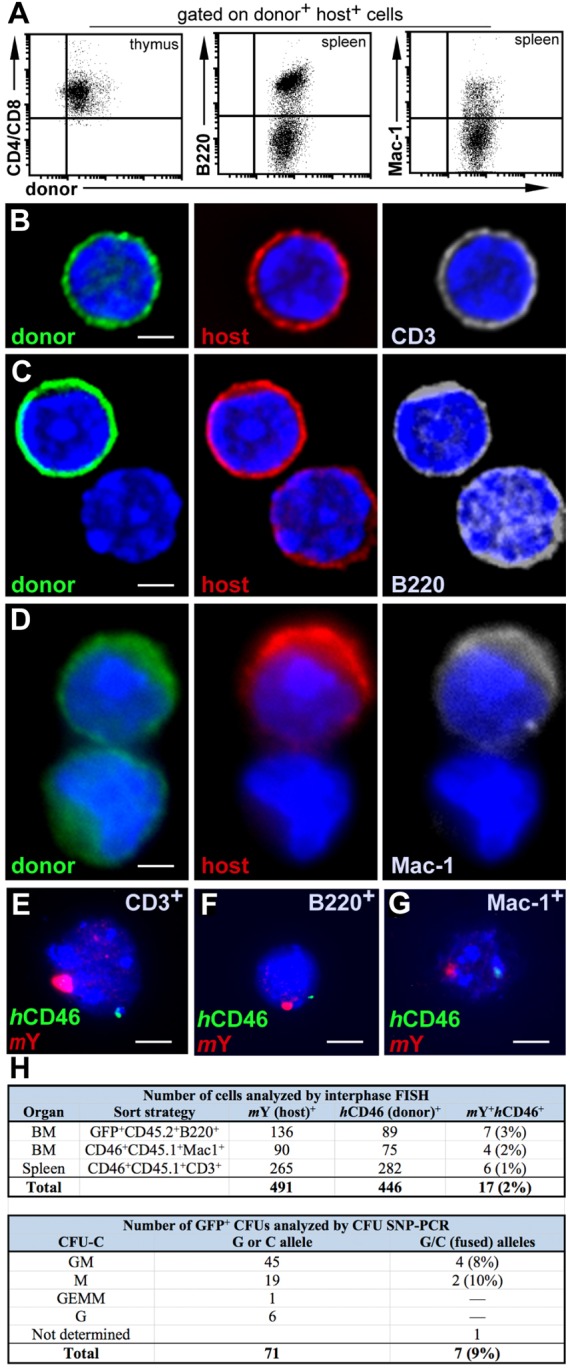

Determination of hematopoietic lineages participating in fusion events

To ascertain the potential lineage restriction of exclusively hematopoietic fusion events generated after transplantation (Fig. 1A), we isolated hematopoietic cells by flow cytometry for co-expression of donor and host immunophenotype and observed expression of T cell (CD3, CD4, CD8), B cell (B220) or macrophage (Mac1) markers (Fig. 2A). Deconvolution fluorescent microscopy further confirmed co-expression of donor, host and select lineage markers in individual cells (Fig. 2B–D), with nuclei containing both donor and host DNA markers identified by interphase FISH at frequencies ranging from 1% to 3% (Fig. 2E–H). Control samples of cells sorted concurrently from the same animals for expression of either donor or host markers did not exhibit evidence of genetic marker blending.

Fig. 2.

Marker co-expression in fusion-derived lymphoid and myeloid cells. (A) Following initial cell sort (Fig. 1A), FACS gates were set to collect CD4+ and/or CD8+ thymic cells (left), B-cell lineage B220+ spleen cells (middle), and myeloid Mac-1+ spleen cells (Wright et al., 2001). (B) Mature CD3+ splenocytes were additionally detected in the CD45.2+ GFP+ B220– fraction of host spleens. Cytospun cells were fixed and stained with anti-GFP Alexa Fluor 488 (green), human CD46–PE (red), CD3–APC (gray) and DAPI (blue). (C) B220+ cells sorted from CD45.1 host spleens were stained with anti-CD45.1–FITC (green), human CD46–PE (red), B220–APC (gray) and DAPI (blue). (D) Staining of Mac-1-sorted splenocytes with anti-CD45.1–FITC (green), human CD46-PE (red), Mac-1-APC (gray), and DAPI (blue). Cells were visualized using deconvolution fluorescent microscopy. Scale bars: 2 µm (B–D). (E) Interphase FISH analysis of CD3+ cells isolated from thymus (F) B220+ cells from spleen (G) or Mac-1+ cells isolated from spleen; cells were probed for mouse Y (red) and human CD46 (green). Scale bars: 5 µm (E–G). (H) Frequency of hematopoietic cell fusion detected by interphase FISH or SNP-PCR. GM, granulocyte or macrophage; M, macrophage; GEMM, granulocyte, erythroid, macrophage or megakaryocyte; G, granulocyte.

To determine the presence of hematopoietic progenitors among fused cells and test their capacity to undergo myeloid differentiation, we plated unfractionated bone marrow of GFP+ hosts (CD45.2 donor) in cytokine-supplemented methycellulose culture to generate clonogenic colonies (CFU-C). Among GFP-expressing colonies, 9% contained SNP-PCR signatures of both donor and host alleles (Fig. 2H). Because our calculated fusion event frequency reflects only those loci represented by FISH or SNP markers, it is probably an underestimate due to anticipated instances of marker loss.

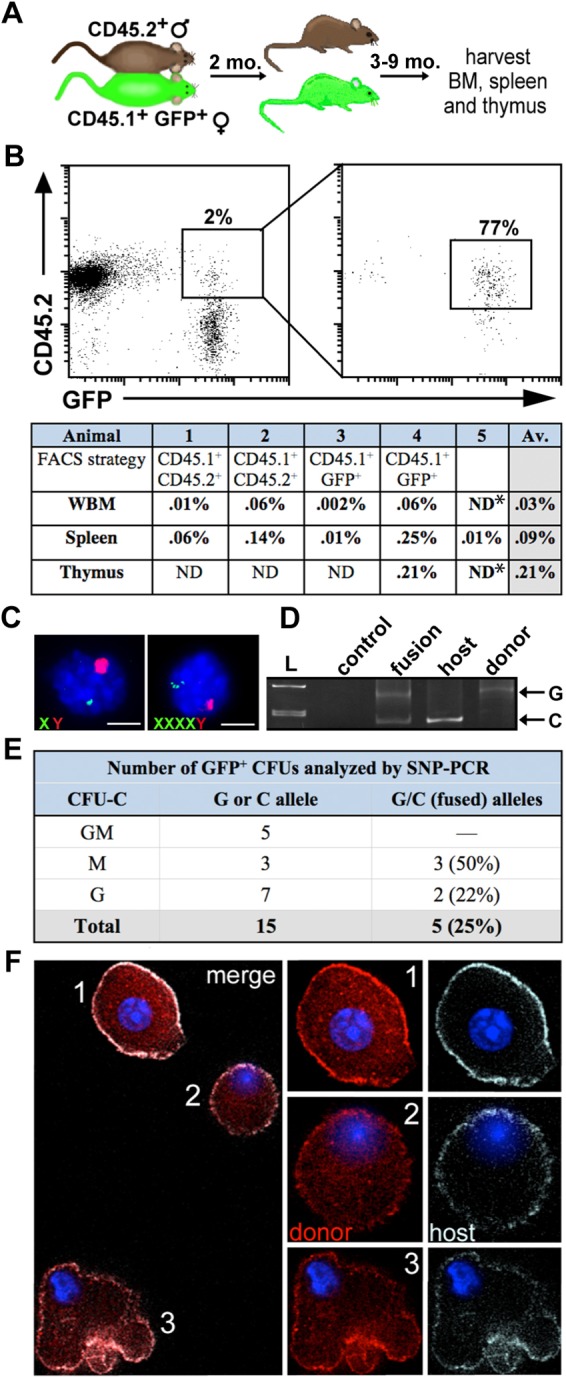

Tissue-specific injury is not required to induce intra-hematopoietic cell fusion events

Experimental models of heterotypic cell fusion use acute tissue damage or inflammation by irradiation or physical injury to initiate cell fusion (Davies et al., 2009; Nygren et al., 2008). To test the requirement for injury induction in intra-hematopoietic fusion we used a parabiosis model (Wright et al., 2001). Congenic, CD45 isotype-mismatched mice were surgically attached to establish cross circulation without injury, resulting in reciprocal parabiont partner bone marrow chimerism between 6% and 27% (Fig. 3A). At time points ranging from 3 to 9 months after separation, cells co-expressing donor and host markers were serially sorted from hematopoietic tissues of individual parabiosis partners (Fig. 3B). The frequency of co-expressing events was comparable to that observed in the transplantation model (Fig. 3B, supplementary material Table S1). For validation in gender-mismatched parabionts, we examined interphase FISH sex chromosome markers in cells isolated from the bone marrow and spleen of animals at several time points after separation. In serially sorted GFP+ (female) CD45.2 populations, we confirmed a subset of cells with evidence of donor and host genetic marker mixing by FISH (Fig. 3C). Analysis of individual CFU-C derived from unfractionated bone marrow from parabiosis pairs involving one GFP+ transgenic partner revealed that approximately 25% of the GFP-expressing colonies possessed both donor and host SNPs (Fig. 3D–F). Clearly, these intra-hematopoietic events were non-abortive and mitotically competent. Thus, independent informative SNP and FISH markers in separate parabiosis models reveal that hematopoietic cells can undergo homotypic fusion in the absence of acute irradiation injury.

Fig. 3.

Hematopoietic cell fusion without injury induction. (A) Schema of the sex-mismatched parabiosis model. (B) FACS plots of CD45.1+ GFP+ splenocytes serially sorted from a GFP+ parabiont depicted in A. *The purity of whole bone marrow and thymus samples sorted from animal 5 was not ascertained; therefore the fusion frequency was not calculated for these tissues. (C) Interphase FISH analysis on fused cells isolated from bone marrow (left) and spleen (right) of sex-mismatched parabionts. Cells were probed for mouse Y (red) and mouse X (green). Scale bars: 5 µm. (D) SNP-PCR analysis performed on fused cells isolated from CFU-C derived from female CD45-mismatched parabionts. A fused cell colony containing SNP markers from both fusion partners is shown alongside controls for each allele. L, ladder. (E) Frequency of CFU-C fusion events detected by SNP-PCR. (F) Individual cells from a clonogenic CFU-C colony isolated from a female CD45-mismatched parabiont. A field of view with several cells from one colony (left) and individual cells enlarged in right panels. CFU-C were cytospun, fixed, and stained with antibodies against donor (CD45.1-PE, red) and host (CD45.2-APC, gray), and visualized using fluorescent deconvolution microscopy.

Frequency of hematopoietic cell fusion events

We used two different methods of screening and enrichment before validation of fusion events by genetic analysis: FACS and GFP+ CFU colony isolation. The frequency of cells co-expressing both parental markers was highest when protein-based assays such as FACS or microscopy were used for detection (supplementary material Fig. S2). This is probably due to cell membrane sharing (trogocytosis) between cells (Yamanaka et al., 2009). As evident from the decreased frequency of fusion events subsequently validated by genetic assays, FACS is suitable for the prospective recovery, but suffers from lower specificity. Conversely, GFP expression-based isolation of CFU-Cs proved a more efficient method. As a host parental marker, GFP represented the minority of plated CFUs. Because CFUs arise from clonal progenitor expansion over 7–10 days in culture, marker expression profiles reflect genomic contributions, rather than residual protein, and provide sensitive and specific validation. As a caveat, the frequency of fusion events in CFUs is biased toward myeloid progenitors; however, it was necessary to use FACS enrichment for all other (i.e. non-clonal) hematopoietic cell types.

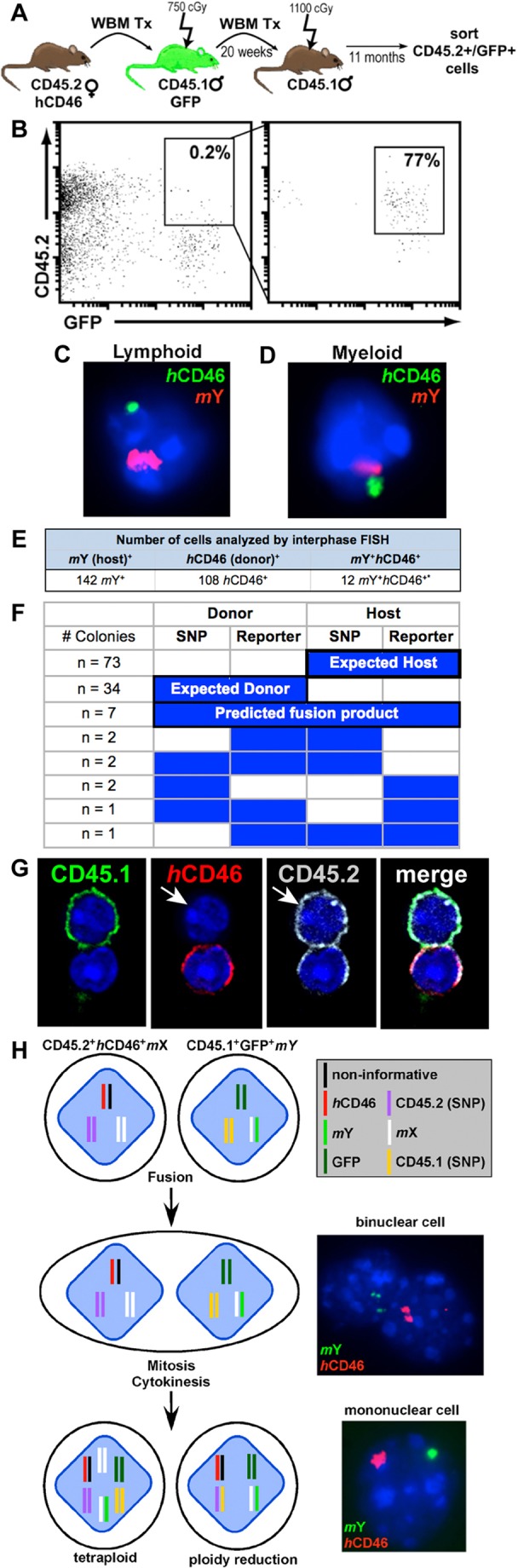

Fused hematopoietic cells do not undergo malignant clonal expansion

We investigated whether hematopoietic multipotent progenitor cells (MPPs) participate in fusion events and found that the bone marrow c-kit+ sca-1+ lineage (KSL) subset in primary transplant recipients contained up to 0.5% of cells co-expressing donor and host markers (not shown). To investigate the functional competence of MPPs, we flow-cytometrically sorted and transplanted whole bone marrow cells co-expressing primary CD45.2 human CD46 donor and GFP+ host markers at up to 1 year after primary transplantation into lethally irradiated CD45.1 GFP− secondary hosts (Fig. 4A,B). When tested by interphase FISH for genetic evidence of marker mixing, both mouse Y and human CD46 were detected in myeloid and lymphoid lineages cells of secondary recipients (Fig. 4C–E). This observation further supports the notion that long-lived MPPs participate in fusion events and these events contribute to hematopoietic repopulation following serial transplantation. Unlike observations of aneuploidy and genetic instability seen after malignant transformation (Chandhok and Pellman, 2009), our data suggest that hematopoietic cells can fuse without apparent myeloid or lymphoid bias among progeny and that genetic markers from both fusion partners are maintained throughout in vitro progenitor differentiation and in vivo repopulation.

Fig. 4.

Fused cells contribute to long-term hematopoiesis in secondary recipients. (A) Secondary transplantation scheme. (B) Cells co-expressing CD45.2+ GFP+ were FACS sorted from spleens collected from secondary hosts. (C) Interphase FISH analysis of a fused lymphoid (CD4, CD8, B220) and (D) myeloid (Mac1, Gr1) cell isolated from spleen. Cells were probed for mouse Y (red) and human CD46 (green). (E) Hematopoietic cells co-expressing donor and host markers isolated from secondary transplant recipients analyzed by interphase FISH. (F) CFU-Cs were isolated from transplant recipients. SNP-PCR and PCR for autosomal reporter genes (CD46 or GFP) was performed on each colony. (G) Whole bone marrow (WBM) was harvested from a primary transplant recipient, FACS sorted for co-expression of parental markers and cytospun onto slides. Cells were stained with antibodies against host (CD45.1, FITC), donor (CD46, PE) and donor (CD45.2, APC). Although all CD46+ cells should be CD45.2+, there were a few instances in which a host marker was acquired and one of the two donor markers was lost. (H) Model of cell fusion. The genetic markers used in our studies are shown for each cell type. Fusion of the cellular membrane results in a binuclear cell containing a nucleus from each parental cell type. Following mitosis and cytokinesis, a daughter cell will be tetraploid or will undergo ploidy reduction to revert to diploid (or near-diploid) state with concurrent gain or loss of excess chromosomal material. In these cases, the daughter cell is mononuclear.

The fusion events discussed here are uniformly hematopoietic in phenotype, with prominent CD45 expression. However, that does not preclude their origin from fusion between a hematopoietic cell and a heterologous cell type with subsequent acquisition of a purely hematopoietic fate (Palermo et al., 2009). Indeed, this would mimic proposed mechanisms for the acquisition of metastatic disease by solid tumors. However, given that no such non-malignant fusion events have been described to date and none of the fusion events described here show malignant evolution, we favor the interpretation of homotypic cell fusion.

Interestingly, examination of donor and host autosomal reporter genes (GFP and CD46) by PCR of CFU-Cs from primary transplant animals revealed independent segregation of alleles in more than half of fusion products. Whereas the donor SNP allele should segregate with the donor reporter allele and the host SNP allele with the host reporter allele, we show several instances (n = 4) in which a donor SNP was found to segregate with an autosomal host reporter, and vice versa (Fig. 4F). We observed additional instances (n = 4) of parental marker loss. These results were corroborated in immunofluorescent deconvolution microscopy studies, in which hybrid cells with loss of a parental marker were observed (Fig. 4G). Despite these genetic changes, we did not detect evidence of malignant hematopoietic transformation in animals at time points up to 17 months after transplantation or parabiosis separation. Each animal was subjected to gross necropsy, and we analyzed peripheral blood and differential leukocyte cell counts, which showed values within normal limits for strain and gender (supplementary material Table S2). Lineage analysis and CFU-C frequencies obtained from primary and secondary animals showed no abnormalities. Thus, although we observed evidence of marker gain by SNP and FISH analysis in lymphoid and myeloid fusion progeny following transplantation and parabiosis, none of the animals demonstrated overt hematopoietic malignancy, lineage restriction or an increasing frequency of homotypic cell fusion progeny over time. Rather, purely hematopoietic fusion events propagate genetically acquired markers for an extended period of time in vivo, without transformation and throughout cytokine-driven clonogenic differentiation in vitro. On the basis of the aggregate SNP and FISH data, we propose the following events to explain how hematopoietic cell–cell fusion can contribute to somatic CNV (Fig. 4H). Subsequent to fusion of the cellular membranes, an intermediate binuclear, tetraploid heterokaryon is formed. Most of the fusion events observed contained a single nucleus with DNA markers from both parental cells, suggesting nuclear reduction and completion of cell division (Duncan et al., 2009; Duncan et al., 2010).

Our findings suggest that long-lived hematopoietic cells might be more tolerant of limited chromosomal sequence gains than anticipated. Somatic adaptation is thought to contribute to clonal variegation in cancer, presumably owing to increased genetic instability of chromosomally imbalanced cells (Anderson et al., 2011). However, CNV following intra-hematopoietic cell fusion could provide a source of non-pathogenic adaptive diversity (Duelli et al., 2005; Muotri et al., 2010; Piotrowski et al., 2008) and might explain reports of unexpected lymphoid and myeloid lineage marker co-expression in hematopoietic progenitors (Balciunaite et al., 2005; Quesenberry and Aliotta, 2008).

In conclusion, this is the first demonstration of hematopoietic cell fusion resulting in functionally competent, non-pathogenic cells from multiple lineages arising under injury or non-injury conditions. We propose intra-hematopoietic cell fusion as a novel platform to investigate somatic variation in the hematopoietic system.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Mice were maintained in a breeding colony in the animal care facility at OHSU. All procedures were approved by the OHSU Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. C57BL/6 background mouse strains used in these studies (from the Jackson Laboratory unless indicated) included: C57BL/6 (CD45.2), C57BL/6Ka-Thy1.1-Ly5.1 (CD45.1), B6.FVB-Tg(CD46)2Gsv/J and C57BL/6-TgN(ACTBEGFP)Osb-YO-1 (referred to as GFP; from Masaru Okabe, Osaka University, Osaka, Japan).

Transplantation studies

Donors and hosts were between 8 and 12 weeks of age at the time of transplant. Female CD46 transgenic donor bone marrow (1×106 unfractionated cells or 1000 Lineage− c-kit+ Sca-1+ cells sorted as described (Goldman et al., 2009) was transplanted into CD45.1 or CD45.1 GFP male recipients following 750 cGy gamma irradiation. For secondary transplant studies, 1×106 unfractionated bone marrow cells from primary hosts were transplanted into lethally irradiated (1150 cGy), 8- to 12-week-old hosts. Donor engraftment was confirmed >4 weeks after transplant by peripheral blood analysis.

Parabiosis

Parabiotic pairs of 6- to 12-week-old age- and weight-matched mice were generated with CD45 congenic GFP+ or GFP− C57Bl/6 mice as previously described (Bailey et al., 2006). For sex-mismatched pairs, males were vasectomized before parabiosis. For all but one parabiotic pair, each mouse was given recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor subcutaneously (human G-CSF; 250 mg/kg) for 4 days, 2–3 weeks after joining. One pair was implanted with mini-osmotic pumps delivering 100 ml per day (7 days total) human G-CSF (300 mg/ml) and AMD3100 (5 mg/kg) 8 weeks after joining. All parabiosis partners were surgically separated 5–6 weeks after GCSF treatment.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting

Cells were prepared from long bones, spleen and thymus of experimental mice. These antibodies (from eBioscience unless indicated) were used in cell sorting: CD46–phycoerythrin (PE), CD45.1–Fluoroscein isothiocyanate (FITC; BD Pharmingen), CD45.1–allophycocyanin (APC), CD45.1–PE (BD Pharmingen), CD45.1–PE–Cy7, CD45.1–APC–efluor 780, CD45.2–APC, CD45.2–PE (BD Pharmingen), F4/80–FITC (Serotec), Mac1–Alexa-Fluor-488, B220–FITC (BD Pharmingen), CD117 (c-kit)–APC–Alexa-Fluor-750, Ly6AE (Sca1)–PE–Cy7 (BD Pharmingen) and an APC-conjugated lineage mixture (B220, Ter119, CD3, CD4, CD5, CD8, Mac1, Gr1; BD Pharmingen). Cells were serially sorted using a BD Influx fluorescence-activated cell sorter. Dead cells were excluded by a combination of scatter gates and propidium iodine, and doublets were eliminated using the pulse-width parameter.

SNP-genotyping PCR

The single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) at D1Mit421.1 (rs3022832) was used to distinguish CD45.2 cells (C allele) and CD45.1 cells (G allele). Nested SNP-PCR was performed on single sorted cells [collected as previously described (Duncan et al., 2009)] and individual CFU-C colonies. Two rounds of PCR (40 cycles each) were performed with Platinum Taq polymerase (Invitrogen) using the outside primers: 5′-TTG TTC AGG GCA TTT GCA CAG CAG-3′ and 5′-TGC AAG AGT GTG TGT GAG TCT GTG-3′ and the internal primers: 5′-GGG TCT GCC TGT CTT TGT CTT TGA-3′ and 5′-GTG TGT GTG TGT GTG TGT GTG TGT-3′. Amplicons were digested overnight with 3 units of SfcI (New England Biolabs) and resolved on a 8% polyacrylamide gel.

Immunofluorescence and deconvolution microscopy

Hematopoietic cells were prepared as previously described (Skinner et al., 2009). Deconvolution microscopy was performed at the OHSU Advanced Light Microscopy Core with, an Olympus IX71 wide field microscope, a Nikon Coolpix HQ Camera, and DeltaVision SoftWoRx software. Deconvolution and color assignments were performed with SoftWoRx software (Applied Precision). Images were acquired using the 60× 1.4 NA oil lens. Z-stacks were acquired at 0.5 µm for the complete depth of the cells and were deconvolved for nine iterations with appropriate point spread function.

Fluorescent in situ hybridization

An Enzo-Green-labeled point probe for human CD46 (human BAC RP11-454L1; from Empire Genomics), mouse Y paint probes (Cy3 labeled from Thermo Scientific and IDye556 labeled from ID Laboratories) and an IDye495-labeled mouse X point probe (ID Laboratories) were used for FISH. Cells were dropped onto non-charged slides and aged by baking for 20 minutes at 90°C. For cohybridization of human CD46 with the mouse Cy3-Y probe, slides were treated with 10 μg/ml RNase for 1 hour at 37°C, washed in 2× SSC, dehydrated in an ethanol series, denatured in 70% formamide, 2× SSC at 72°C for 3 minutes, and then dehydrated in an ice-cold ethanol series and air dried. Probes diluted in hybridization buffer were denatured at 75°C for 10 minutes and then 37°C for 30–60 minutes, and added to slides. Hybridizations were performed overnight at 37°C. Slides were sequentially washed at 43°C in 50% formamide, 2× SSC and 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 8, with 0.1% IGEPAL ca-360 and mounted in Prolong Gold (Invitrogen) containing DAPI. For cohybridization of the IDye556 mouse Y probe with the human CD46 probe or the mouse X probe, the protocol from ID Laboratories was followed. Cells were analyzed and photographed with a Zeiss Axiophot 200 microscope using a 100× 1.3 NA Zeiss ECplan-NEOFLUAR objective, a monochromatic AxioCam camera and standard epifluorescence filters for fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), Cy3 and DAPI (Carl Zeiss). Fluorescent images were digitally combined using AxioVision software (Carl Zeiss).

Colony forming unit-culture assays

Unfractionated bone marrow was plated at a density of 20,000 nucleated cells per ml in Methocult GF methylcellulose (M3434, Stem Cell Technologies or HSC007, R&D Systems) and incubated at 37°C. After 7–12 days of culture, individual, non-overlapping colonies were harvested.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Andrea McBeth, Pamela Canaday and Devorah Goldman for experimental assistance and expertise in SNP-PCR, cell sorting and interphase FISH, respectively.

Footnotes

Funding

The project was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) [grant number HL90765 to P.K. and HL095351 to A.M.S.]; and the National Institutes of Health [grant number HL069133 to William H. Fleming]. The content does not necessarily represent the official views of the NHLBI or the NIH. Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Supplementary material available online at http://jcs.biologists.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1242/jcs.100123/-/DC1

References

- Anderson K., Lutz C., van Delft F. W., Bateman C. M., Guo Y., Colman S. M., Kempski H., Moorman A. V., Titley I., Swansbury J., et al. (2011). Genetic variegation of clonal architecture and propagating cells in leukaemia. Nature 469, 356–361 10.1038/nature09650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey A. S., Willenbring H., Jiang S., Anderson D. A., Schroeder D. A., Wong M. H., Grompe M., Fleming W. H. (2006). Myeloid lineage progenitors give rise to vascular endothelium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 13156–13161 10.1073/pnas.0604203103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balciunaite G., Ceredig R., Massa S., Rolink A. G. (2005). A B220+ CD117+ CD19- hematopoietic progenitor with potent lymphoid and myeloid developmental potential. Eur. J. Immunol. 35, 2019–2030 10.1002/eji.200526318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandhok N. S., Pellman D. (2009). A little CIN may cost a lot: revisiting aneuploidy and cancer. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 19, 74–81 10.1016/j.gde.2008.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho K. S., Hill A. B. (2008). T cell acquisition of APC membrane can impact interpretation of adoptive transfer experiments using CD45 congenic mouse strains. J. Immunol. Methods 330, 137–145 10.1016/j.jim.2007.10.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad D. F., Pinto D., Redon R., Feuk L., Gokcumen O., Zhang Y., Aerts J., Andrews T. D., Barnes C., Campbell P., et al. Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium (2010). Origins and functional impact of copy number variation in the human genome. Nature 464, 704–712 10.1038/nature08516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies P. S., Powell A. E., Swain J. R., Wong M. H. (2009). Inflammation and proliferation act together to mediate intestinal cell fusion. PLoS ONE 4, e6530 10.1371/journal.pone.0006530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duelli D. M., Hearn S., Myers M. P., Lazebnik Y. (2005). A primate virus generates transformed human cells by fusion. J. Cell Biol. 171, 493–503 10.1083/jcb.200507069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan A. W., Hickey R. D., Paulk N. K., Culberson A. J., Olson S. B., Finegold M. J., Grompe M. (2009). Ploidy reductions in murine fusion-derived hepatocytes. PLoS Genet. 5, e1000385 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan A. W., Taylor M. H., Hickey R. D., Hanlon Newell A. E., Lenzi M. L., Olson S. B., Finegold M. J., Grompe M. (2010). The ploidy conveyor of mature hepatocytes as a source of genetic variation. Nature 467, 707–710 10.1038/nature09414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman D. C., Bailey A. S., Pfaffle D. L., Al Masri A., Christian J. L., Fleming W. H. (2009). BMP4 regulates the hematopoietic stem cell niche. Blood 114, 4393–4401 10.1182/blood-2009-02-206433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings P. J., Lupski J. R., Rosenberg S. M., Ira G. (2009). Mechanisms of change in gene copy number. Nat. Rev. Genet. 10, 551–564 10.1038/nrg2593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes O. R., Stewart R., Dimmick I., Jones E. A. (2009). A critical appraisal of factors affecting the accuracy of results obtained when using flow cytometry in stem cell investigations: where do you put your gates? Cytometry 75A, 803–810 10.1002/cyto.a.20764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson C. B., Youssef S., Koleckar K., Holbrook C., Doyonnas R., Corbel S. Y., Steinman L., Rossi F. M., Blau H. M. (2008). Extensive fusion of haematopoietic cells with Purkinje neurons in response to chronic inflammation. Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 575–583 10.1038/ncb1720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCulloch E. A., Till J. E. (1960). The radiation sensitivity of normal mouse bone marrow cells, determined by quantitative marrow transplantation into irradiated mice. Radiat. Res. 13, 115–125 10.2307/3570877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muotri A. R., Marchetto M. C., Coufal N. G., Oefner R., Yeo G., Nakashima K., Gage F. H. (2010). L1 retrotransposition in neurons is modulated by MeCP2. Nature 468, 443–446 10.1038/nature09544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nygren J. M., Liuba K., Breitbach M., Stott S., Thorén L., Roell W., Geisen C., Sasse P., Kirik D., Björklund A., et al. (2008). Myeloid and lymphoid contribution to non-haematopoietic lineages through irradiation-induced heterotypic cell fusion. Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 584–592 10.1038/ncb1721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palermo A., Doyonnas R., Bhutani N., Pomerantz J., Alkan O., Blau H. M. (2009). Nuclear reprogramming in heterokaryons is rapid, extensive, and bidirectional. FASEB J. 23, 1431–1440 10.1096/fj.08-122903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piotrowski A., Bruder C. E. G., Andersson R., Diaz de Ståhl T., Menzel U., Sandgren J., Poplawski A., von Tell D., Crasto C., Bogdan A., et al. (2008). Somatic mosaicism for copy number variation in differentiated human tissues. Hum. Mutat. 29, 1118–1124 10.1002/humu.20815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quesenberry P. J., Aliotta J. M. (2008). The paradoxical dynamism of marrow stem cells: considerations of stem cells, niches, and microvesicles. Stem Cell Rev. 4, 137–147 10.1007/s12015-008-9036-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizvi A. Z., Swain J. R., Davies P. S., Bailey A. S., Decker A. D., Willenbring H., Grompe M., Fleming W. H., Wong M. H. (2006). Bone marrow-derived cells fuse with normal and transformed intestinal stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 6321–6325 10.1073/pnas.0508593103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner A. M., O'Neill S. L., Kurre P. (2009). Cellular microvesicle pathways can be targeted to transfer genetic information between non-immune cells. PLoS ONE 4, e6219 10.1371/journal.pone.0006219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres E. M., Dephoure N., Panneerselvam A., Tucker C. M., Whittaker C. A., Gygi S. P., Dunham M. J., Amon A. (2010). Identification of aneuploidy-tolerating mutations. Cell 143, 71–83 10.1016/j.cell.2010.08.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Willenbring H., Akkari Y., Torimaru Y., Foster M., Al–Dhalimy M., Lagasse E., Finegold M., Olson S., Grompe M. (2003). Cell fusion is the principal source of bone-marrow-derived hepatocytes. Nature 422, 897–901 10.1038/nature01531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wersto R. P., Chrest F. J., Leary J. F., Morris C., Stetler–Stevenson M. A., Gabrielson E. (2001). Doublet discrimination in DNA cell-cycle analysis. Cytometry 46, 296–306 10.1002/cyto.1171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willenbring H., Bailey A. S., Foster M., Akkari Y., Dorrell C., Olson S., Finegold M., Fleming W. H., Grompe M. (2004). Myelomonocytic cells are sufficient for therapeutic cell fusion in liver. Nat. Med. 10, 744–748 10.1038/nm1062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright D. E., Wagers A. J., Gulati A. P., Johnson F. L., Weissman I. L. (2001). Physiological migration of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Science 294, 1933–1936 10.1126/science.1064081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka N., Wong C. J., Gertsenstein M., Casper R. F., Nagy A., Rogers I. M. (2009). Bone marrow transplantation results in human donor blood cells acquiring and displaying mouse recipient class I MHC and CD45 antigens on their surface. PLoS ONE 4, e8489 10.1371/journal.pone.0008489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yannoutsos N., Ijzermans J. N., Harkes C., Bonthuis F., Zhou C. Y., White D., Marquet R. L., Grosveld F. (1996). A membrane cofactor protein transgenic mouse model for the study of discordant xenograft rejection. Genes Cells 1, 409–419 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1996.d01-244.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zebedee S. L., Barritt D. S., Raschke W. C. (1991). Comparison of mouse Ly5a and Ly5b leucocyte common antigen alleles. Dev. Immunol. 1, 243–254 10.1155/1991/52686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F., Gu W., Hurles M. E., Lupski J. R. (2009). Copy number variation in human health, disease, and evolution. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 10, 451–481 10.1146/annurev.genom.9.081307.164217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.