Abstract

The molecular mechanisms that regulate and coordinate signaling between the extracellular matrix (ECM) and cells contributing to the developing vasculature are complex and poorly understood. Myocardin-like protein 2 (MKL2) is a transcriptional co-activator that in response to RhoA and cytoskeletal actin signals physically associates with serum response factor (SRF), activating a subset of SRF-regulated genes. We now report the discovery of a previously undescribed MKL2/TGFβ signaling pathway in embryonic stem (ES) cells that is required for maturation and stabilization of the embryonic vasculature. Mkl2–/– null embryos exhibit profound derangements in the tunica media of select arteries and arterial beds, which leads to aneurysmal dilation, dissection and hemorrhage. Remarkably, TGFβ expression, TGFβ signaling and TGFβ-regulated genes encoding ECM are downregulated in Mkl2–/– ES cells and the vasculature of Mkl2–/– embryos. The gene encoding TGFβ2, the predominant TGFβ isoform expressed in vascular smooth muscle cells and embryonic vasculature, is activated directly via binding of an MKL2/SRF protein complex to a conserved CArG box in the TGFβ2 promoter. Moreover, Mkl2–/– ES cells exhibit derangements in cytoskeletal organization, cell adhesion and expression of ECM that are rescued by forced expression of TGFβ2. Taken together, these data demonstrate that MKL2 regulates a conserved TGF-β signaling pathway that is required for angiogenesis and ultimately embryonic survival.

Keywords: Angiogenesis, Embryonic stem cell, Myocardin-related transcription factor B/MKL2, Mouse, Transforming growth factor β

INTRODUCTION

Angiogenesis and vascular patterning are dependent upon the capacity of vascular smooth muscle cells (SMCs) to transduce biomechanical and humoral signals that influence cell differentiation, migration, proliferation and survival (Owens, 1998; Owens et al., 2004). Under homeostatic conditions, vascular SMCs assume a spindle-like morphology with a rich, well-organized cytoskeleton expressing abundant SMC-restricted contractile proteins that together define the contractile properties of this muscle cell lineage. Within the arterial wall, signals transduced directly from endothelial cells and the extracellular matrix (ECM) regulate the physiological properties of SMCs (Astrof and Hynes, 2009; Hayward et al., 1995; Thyberg and Hultgårdh-Nilsson, 1994). The signals transduced between ECM components and vascular SMCs play crucial roles in regulating embryonic angiogenesis and contribute to pathogenesis of atherosclerosis and the formation of arterial aneurysms (Raines, 2000).

Our group and others have shown that the MADS box transcription factor, serum response factor (SRF), acting in concert with transcriptional co-activators in the myocardin-related transcription factor (MRTF) family, including myocardin, myocardin-like protein 1 (MKL1) and myocardin-like protein 2 (MKL2), promote the contractile SMC phenotype (Parmacek, 2007). Forced expression of any member of the MRTF family in embryonic stem (ES) cells activates transcription of endogenous genes encoding SMC-restricted contractile proteins (Du et al., 2004; Du et al., 2003). In response to Rho/actin signaling, MKL1 and MKL2 localize to the nucleus where they physically associate with SRF and activate transcription of a subset of genes associated with cytoskeletal organization (Sotiropoulos et al., 1999).

Two lines of genetically engineered mice that harbor loss-of-function mutations in the Mkl2 gene have been described (Li et al., 2005; Oh et al., 2005; Wei et al., 2007). Mice containing an Mkl2 insertional gene trap mutation located between exons 10 and 11 exhibit a hypomorphic phenotype. Gene trap mutant mice survive to birth, but die within 48 hours, exhibiting a spectrum of cardiac outflow tract and great artery patterning defects that are attributable to a cell-autonomous block in differentiation of neural crest-derived vascular SMCs (Li et al., 2005; Wei et al., 2007). Defects in development of the vitelline system that produces the liver sinusoids are also observed in Mkl2 gene trap mutant embryos (Wei et al., 2007). By contrast, Mkl2–/– embryos survive until embryonic day (E) 13.5-14.5 and they also demonstrate defective remodeling of the pharyngeal arch arteries and cardiac outflow tract, recapitulating common forms of congenital heart disease (Oh et al., 2005). In addition, Mkl2–/– embryos develop pericardial edema and hemorrhage (Oh et al., 2005). However, the observed defects in vascular patterning in Mkl2–/– null embryos fails to explain lethality at mid-gestation, raising questions of what other functions are mediated by MKL2 in differentiating cells and the embryo.

Multiple studies have shown that TGFβ signaling plays a crucial role in development of the great arteries (Pardali et al., 2010). TGFβ signaling influences vascular SMC shape, migration, homing and location through processes that are controlled by cell-surface transmembrane receptors and components of the extracellular matrix (ECM) (Massagué, 1990). TGFβ2 and, to a lesser extent, TGFβ3 are expressed by vascular SMCs (Molin et al., 2003). Genetic studies in mice and humans have shown that disruption of TGFβ signaling pathways results in defects in vasculogenesis and angiogenesis that are attributable, at least in part, to vascular SMCs (Pardali et al., 2010). Mice in which the Tgbr2 gene was conditionally ablated in vascular SMC precursors display arterial dilation and aneurysm formation, which leads to late embryonic lethality (Choudhary et al., 2009).

To examine the function of MKL2 in the developing embryo, we generated and characterized Mkl2–/– ES cells and mouse embryos. By mid-gestation, Mkl2–/– embryos develop aneurysmal dilation and dissection of the aorta, carotid arteries and select arterial beds throughout the embryo. Mkl2–/– mutant arteries display disruption of the tunica media with alterations in SMC morphology, alignment and investment of ECM. Surprisingly, analysis of Mkl2–/– ES cells revealed defects in cell adhesion that are attributable to a block in TGFβ signaling and TGFβ-regulated genes that encode ECM. Consistent with these data, TGFβ expression, TGFβ signaling and the expression of TGFβ-regulated genes encoding ECM are disrupted in the vasculature of Mkl2–/– embryos. Moreover, Tgfb2 is activated directly via binding of an MKL2/SRF complex to the Tgfb2 promoter. These data reveal an MKL2/TGFβ-dependent signaling pathway in ES cells that is also required for development and structural integrity of the embryonic vasculature.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation and characterization of Mkl2 null mice

An Mkl2 gene-targeting vector was constructed via recombineering with a BAC (BAC/PAC Resources, clone number BAC RP23-402A16) as described previously (Lee et al., 2001) (supplementary material Fig. S1). Conditionally targeted Mkl2+/F ES cells were transiently transfected with the pCMV-Cre expression plasmid to generate heterozygous Mkl2+/– ES cells. Mkl2+/– ES cells were re-targeted via electroporation with the linearized Mkl2 conditional targeting vector (supplementary material Fig. S1A). Mkl2–/F ES cells were transfected with the pTurbo-Cre plasmid (Washington University, St Louis, MO) generating homozygous Mkl2–/– ES cells. To generate Mkl2–/– ES cells that stably express TGFβ2, Mkl2–/– and wild-type ES cells were stably transfected with the pIRES2-TGFβ2-EGFP vector that expresses TGFβ2 and EGFP. Conditionally targeted Mkl2+/F ES cells were microinjected into C57BL/6 donor blastocysts as described previously (Morrisey et al., 1998). Southern blot analysis was performed to confirm that the conditionally targeted Mkl2+/F allele was passed through the germline (supplementary material Fig. S1). To create a germline mutation in the Mkl2 gene, Mkl2F/F mice were interbred with CMV-Cre transgenic mice. Genotype analyses were performed by Southern blot or by PCR as described previously (Li et al., 2005). PCR genotyping primers can be found in supplementary material Table S1. All animal experimentation was performed under protocols approved by the University of Pennsylvania IACUC and in accordance with NIH guidelines.

Histology and immunohistochemistry

Standard histology and immunohistochemistry protocols are available at http://www.med.upenn.edu/mcrc/histology_core (IHC in paraffin section and H&E staining) and http://www.med.upenn.edu/mcrc/histology_core/culturedcells/shtml. F-actin expression was assessed by staining with rhodamine-tagged phalloidin (Invitrogen, catalog code R415) and G-actin was identified with FITC-stained DNase I (Invitrogen, catalog code D12371). A list of the antibodies used is provided in supplementary material Table S2.

Immunoblot and ELISA analyses

Immunoblot analyses were performed as described previously (Li et al., 2005). The concentration of secreted fibronectin in ES cells was determined using the mouse fibronectin ELISA (Cell Application, catalog code CL0351). ES cells (1.0×106/well) were seeded in six-well plates with 2 ml medium for 1 hour and the medium was collected for measurement of secreted fibronectin. Data are expressed as ng fibronectin/ml±s.e.m.

Microarray analysis

Total RNA was extracted from wild-type and Mkl2–/– ES cells using the RNeasy protocol (Invitrogen), yielding RNA for two wild-type and three Mkl2–/– samples. Each sample was hybridized with Affymetrix Mouse Gene ST 1.0 microarrays according to standard protocols. Raw.cel files were normalized using the RMA algorithm, and exploratory analyses compared fold change in expression in Mkl2–/– versus control. These data were deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) public database (Accession Number GSE38316). To screen for signaling pathways affected by Mkl2 deletion, Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) was performed using all signaling pathways described in the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) in the Molecular Signature Database (Subramanian et al., 2005).

qRT-PCR

The sequences of the PCR primers are listed in supplementary material Table S1. Target genes were amplified by PCR with Power SYBR green (Applied Biosystems, catalog number 4309155) as described previously (Du et al., 2004). All reactions were run in triplicate, and relative gene expression was calculated against a GAPDH standard as described previously (Du et al., 2004). Data are expressed as mean gene expression (arbitrary units)±s.e.m.

Transient transfection analyses

The pTGFβ2.luc luciferase reporter plasmid contains the mouse 1.7 kb mouse TGFβ2 promoter subcloned into pGL3-Basic plasmid (Promega). The pTGFβ2 μCArG1.luc plasmid is identical to pTGFβ2.luc, except the TGFβ2 promoter contains a 2 bp mutation in CArG1 that abolishes binding of SRF to the TGFβ2 promoter. Cos-7 cells (2×105/well) were transiently co-transfected with 400 ng luciferase reporter plasmid, 100-400 ng of pcDNA3 control or pcDNA3-based expression plasmid and 5ng Renilla reference plasmid (pRL-TK) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Luciferase and Renilla assays were performed with the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega, catalog code TM040). Smad signaling activity was measured in Mkl2–/– ES cells using Cignal SMAD Reporter Kit (Qiagen, catalog code CCS-017L). All experiments were performed with duplicate plates of cells run in triplicate for each time point. Data are expressed as mean relative luciferase activity±s.e.m.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation analyses

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays were performed with DNA harvested from wild-type and Mkl2–/– ES cells using a ChIP assay kit according to the manufacturer’s directions (Millipore, catalog code 17-295). Polyclonal anti-SRF IgG (Santa Cruz, catalog code Sc335) or control rabbit IgG was used to immunoprecipitate cross-linked chromatin. Quantitative PCR was performed with Power SYBR Green PCR Mastermix and the PRISM 7500 (ABI). The nucleotide sequence of PCR primers used to amplify Tgfβ2 CArG boxes 1-5 are shown in supplementary material Table S1.

Cell adhesion assays

Cell adhesion assays were performed using the Vybrant Cell Adhesion Assay kit (Invitrogen, cat. V-13181). ES cells (5×106/ml) were grown in 0.5% fetal bovine serum for 2 hours and then stained with calcein-AM. Following 1 hour of incubation on plastic or fibronectin-coated tissue culture wells, the fluorescence intensity (O.D.) of each well was measured. The percentage of adherent cells was determined by dividing the fluorescence intensity (O.D.) by the total fluorescence intensity of adherent cells in each well. Each experiment was repeated at least three times. Data are reported as the mean percentage of adherent cells±s.e.m.

Statistical analyses

Statistical significance was determined using the Student’s t-test: *P<0.05; **P<0.01. For GSEA, significance of pathway enrichment in the setting of multiple comparisons was assessed using false discovery rate q-values as previously described (Subramanian et al., 2005). For ChIP analyses, statistical significance was determined with a one-way ANOVA test.

RESULTS

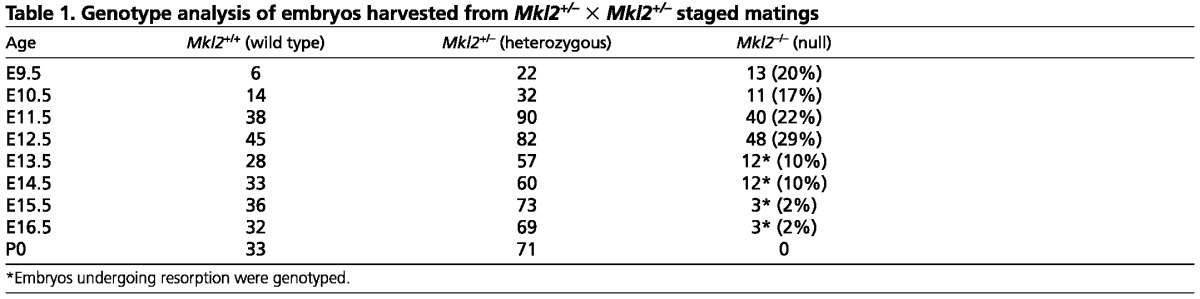

Mkl2–/– null mutant mice survive only until E13.5

Heterozygous Mkl2 (Mkl2+/–) mice were generated in which exon 8 was deleted, rendering the protein functionally null (supplementary material Fig. S1) (Wang et al., 2002). Mkl2–/– embryos survive until E13.5, but die between E13.5 and E16.5 (Table 1). At E15.5, fewer than 10% of the anticipated Mkl2–/– mutants survived and no viable Mkl2–/– embryos were observed beyond E16.5. Of note, the timing of embryonic demise is earlier than we observed in Mkl2 gene trap mutants that exhibit a hypomorphic phenotype and survive until postnatal day (P) 1-2 (Li et al., 2005). Consistent with previous reports (Li et al., 2005; Oh et al., 2005), cardiac outflow tract patterning defects were observed in E14.5-16.5 Mkl2–/– embryos (data not shown). However, these defects failed to explain lethality at E13.5-16.5, which is prior to the transition from the fetal to the adult circulation that occurs in the immediate postnatal period.

Table 1.

Genotype analysis of embryos harvested from Mkl2+/– × Mkl2+/– staged matings

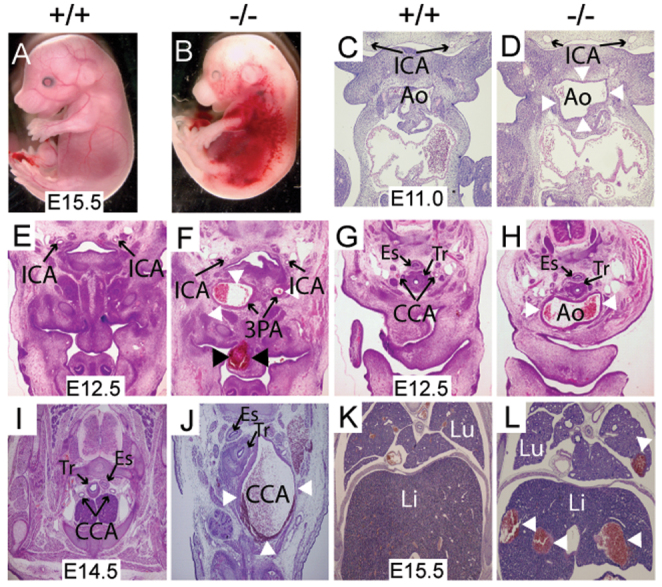

Mkl2 null embryos develop arterial aneurysms and hemorrhage

Analyses of 859 embryos revealed that through E10.5, wild-type (Mkl2+/+), heterozygous (Mkl2+/–) and null (Mkl2–/–) embryos were grossly indistinguishable. However, as early as E11.5, prior to aorticopulmonary septation, some Mkl2–/– embryos exhibited areas of focal hemorrhage. By E12.5, all Mkl2–/– mutants displayed regions of hemorrhage and all surviving E15.5 mutant embryos displayed large areas of hemorrhage covering their bodies (Fig. 1A,B). Histological analyses revealed dilation of the midline derivative of the ventral aorta (Ao) in all E11.0 Mkl2–/– embryos (Fig. 1C,D, white arrowheads). By E12.5, aneurysmal dilation (white arrows) of the aortic arch (Ao) (Fig. 1G,H) and 3rd pharyngeal arch artery (3PA) (Fig. 1E,F) was commonly observed in Mkl2–/– embryos. Aneurysmal dilation and arterial rupture (black arrows) was also observed in other arteries supplying the head and neck of Mkl2–/– embryos (Fig. 1F, arrows). In mutant embryos that survived to E15.5, massive aneurysmal dilation of the common carotid artery (CCA) was observed displacing the trachea (Tr) and esophagus (Es) (Fig. 1I,J). In addition, intraparenchymal hemorrhage of the embryonic liver and lung (white arrows) was observed in E12.5-15.5 Mkl2–/– mutant embryos (Fig. 1K,L). Taken together, these data suggest strongly that hemorrhage attributable to defects in select arteries contributed to the demise of Mkl2–/– embryos.

Fig. 1.

Mkl2–/– embryos exhibit hemorrhage and aneurysmal dilation of the great arteries. (A,B) E15.5 wild-type (+/+) and Mkl2–/– (–/–) embryos demonstrating diffuse hemorrhage in the E15.5 mutant embryo. (C,D) Hematoxylin and Eosin-stained transverse sections of E11.0 wild-type and Mkl2–/– embryo, demonstrating dilated aortic sac (Ao) (arrowheads) in the mutant embryo. Original magnification was ×20. ICA, internal carotid artery. (E,F) Hematoxylin and Eosin-stained transverse section of E12.5 wild-type and Mkl2–/– embryo, demonstrating dilation of the 3rd PA artery and dilation and hemorrhage (black arrowheads) of the lingual vessels in the Mkl2–/– mutant embryo. Original magnification was ×20. White arrowheads indicate aneurysm. (G,H) Hematoxylin and Eosin-stained section of E12.5 wild-type and Mkl2–/– embryo, showing dilation of the mutant aorta (Ao, white arrowheads) extending to the level of the common carotid artery (CCA). Original magnification was ×20. ES, esophagus; Tr, trachea. (I,J) Hematoxylin and Eosin-stained transverse section of E14.5 wild-type and Mkl2–/– embryo, demonstrating aneurysmal dilation of the mutant common carotid artery (CCA). Original magnification was ×20. Arrowheads indicate aneurysm. (K,L) Hematoxylin and Eosin-stained frontal sections of E15.5 wild-type and Mkl2–/– embryos showing intra-parenchymal hemorrhages (white arrowheads) in the liver (Li) and lung (Lu) of the mutant embryo. Original magnification was ×20.

Disruption of the tunica media and structural integrity of Mkl2–/– arteries

Striking defects in the structural organization of the tunica media was observed in E12.5-15.5 Mkl2–/– arteries. In E12.5 Mkl2–/– embryos, the aortic sac (Ao) had enlarged and expanded rostrally into the neck beyond the level normally occupied by the 6th pharyngeal arch artery (Fig. 2A,B). The tunica media of the mutant aorta was thickened in some sections and reduced to a single layer of cells (arrow) in other sections (Fig. 2C,D). At E15.5, SMCs populating the aortic arch of control embryos are distinguished by their spindle-like morphology (arrows) and layered structure (Fig. 2E,G). By contrast, the tunica media of Mkl2–/– embryos was populated with rounded heterogeneous cells lacking a predominant orientation with obvious gaps appearing between cells (Fig. 2F,H). Disruption of the tunica media was even more striking in the common carotid arteries (CCA) of E13.5-15.5 Mkl2–/– embryos (Fig. 2I-P). At E13.5, aneurysmal dilation, dissection and rupture (arrow) of the CCA was commonly observed in Mkl2–/– embryos (Fig. 2J,L). By contrast, three or four layers of circumferentially oriented vascular SMCs comprise the tunica media of wild-type littermates (Fig. 2I,K). Immunostaining with anti-tropoelastin antibody demonstrates disruption of cell-cell and cell-matrix relationships in Mkl2–/– carotid arteries compared with controls (supplementary material Fig. S2). Complex aneurysm formation and dissection with formation of a neointima that recapitulated pathological changes observed in humans was commonly observed in E15.5 Mkl2–/– carotid arteries (Fig. 2M-P). At E15.5, the tunica media of the carotid artery in wild-type embryos consists of four or five layers of well-organized, spindle-shaped SMCs (Fig. 2M,O). By contrast, gaps in the tunica media with penetrating hemorrhage (arrow) were observed in Mkl2–/– embryos and both medial and neointimal vascular SMCs were characterized by marked heterogeneity in size and orientation (Fig. 2N,P).

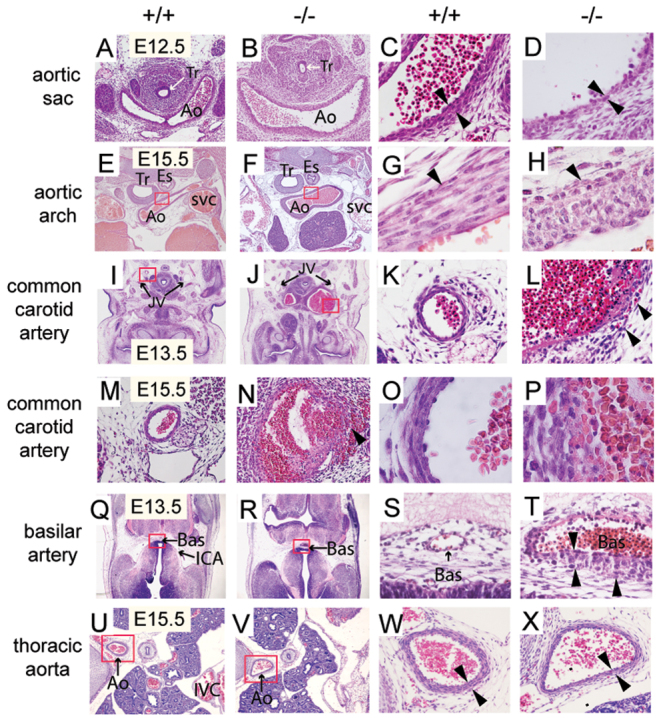

Fig. 2.

Disruption of the tunica media and aneurysm formation in Mkl2–/– embryos. (A-D) Hematoxylin and Eosin-stained transverse section of E12.5 wild-type (+/+) and Mkl2–/– (–/–) embryos, demonstrating dilation of the mutant aortic sac in the Mkl2–/– mutant aorta (Ao). Tr, trachea. (C,D) High-power magnification of the wall of the aortic sac reveals thinning of the tunica media to a single layer of cells (arrowheads) in some segments of the Mkl2–/– mutant aortic sac. Original magnifications were ×100 (A,B) and ×400 (C,D). Tr, trachea. (E-H) Hematoxylin and Eosin-stained transverse section of the aortic arch (Ao) of E15.5 wild-type and Mkl2–/– embryo, demonstrating dilation of mutant aorta arch (Ao). The red rectangles in E and F indicate the locations of G and H. (G,H) High-power magnification of the tunica media (arrowhead) of the control artery reveals spindle-shaped SMCs oriented circumferentially (G); by contrast, medial SMCs populating the mutant artery appear polygonal lacking predominant orientation with obvious gaps between cells (H). Original magnifications were ×40 (E,F) and ×1000 (G,H). (I-L) Hematoxylin and Eosin-stained transverse section demonstrating aneurysmal dilation of the common carotid arteries of E13.5 wild-type and Mkl2–/– embryos. The location of the jugular vein (JV) is indicated. The red rectangles indicate the locations of K and L. (K,L) High-power magnification reveals thinning of the tunica media and rupture through the arterial wall (arrowheads) of the in the Mkl2–/– embryo (L). By contrast, spindle-like SMCs compose the media of the control artery (K). Original magnifications were ×20 (I,J) and ×200 (K,L). (M-P) Hematoxylin and Eosin-stained section showing the common carotid artery of E15.5 wild-type and Mkl2–/– embryo, demonstrating aneurysmal dilation, dissection and rupture (arrowhead) in the Mkl2–/– embryo (N). (O,P) High-power magnification demonstrates alignment of spindle-shaped SMCs surrounding the lumen of the control carotid artery (O). By contrast, SMCs of the Mkl2–/– artery are polygonal, lacking predominant orientation with intramural hemorrhage observed between cells (P). Original magnifications were ×100 (M,N) and ×1000 (O,P). (Q-T) Hematoxylin and Eosin-stained section of the basilar artery (Bas) of E13.5 wild-type and Mkl2–/– embryos demonstrating dilation of the mutant basilar artery (Bas) (R,T). The red rectangles in Q and R indicate the locations of S and T. (S,T) High-power magnification reveals disorganization of the tunica media (arrowheads) in the Mkl2–/– artery compared with the control basilar artery, which comprises a single layer of SMCs. Original magnifications were ×40 (Q,R) and ×400 (S,T). ICA, internal carotid artery. (U-X) Hematoxylin and Eosin-stained section showing the descending thoracic aorta of E15.5 wild-type (U,W) and Mkl2–/– (V,X) embryos. The red rectangles in U and V indicate the locations of W and X. Slight thinning of the tunica media (arrowheads) is observed in the Mkl2–/– mutant artery (X) compared with the control aorta (W). Original magnifications were ×40 (U,V) and ×200 (W,X). IVC, inferior vena cava. See also supplementary material Fig. S2.

Inspection of the cerebral vasculature revealed dilation of the basilar artery in Mkl2–/– embryos compared with controls (Fig. 2Q-T). At E13.5, the lumen of the basilar (Bas) artery is typically surrounded by a single layer of circumferentially oriented SMA-positive vascular SMCs (Fig. 2Q,R). However, the basilar artery of Mkl2–/– mutants was markedly dilated and the lumen was surrounded by multiple layers of heterogeneous appearing cells (arrowheads) expressing SMC markers (Fig. 2S,T; supplementary material Fig. S5). Of note, SMCs contributing to the basilar artery are not derived from the cardiac neural crest. By contrast, only subtle differences were also observed in the descending thoracic aorta of E15.5 Mkl2–/– mutant compared with control littermates (Fig. 2U-X). In mutant embryos, the lumen of the thoracic aorta appeared eccentric with some thinning of the tunica media (arrows) compared with control littermates (Fig. 2V,X). Moreover, no obvious changes were observed in the iliac or femoral arteries of Mkl2–/– and control littermates. However, intra-parenchymal hemorrhage (white arrows) of the liver (Li) and lung (Lu) was commonly observed in E12.5-15.5 Mkl2–/– embryos (Fig. 1L). Taken together, these data demonstrate that the hemorrhage observed in Mkl2–/– embryos is attributable to defects in the structural integrity of select arteries owing to alterations in medial SMC morphology, orientation, and cell-cell and cell-ECM relationships.

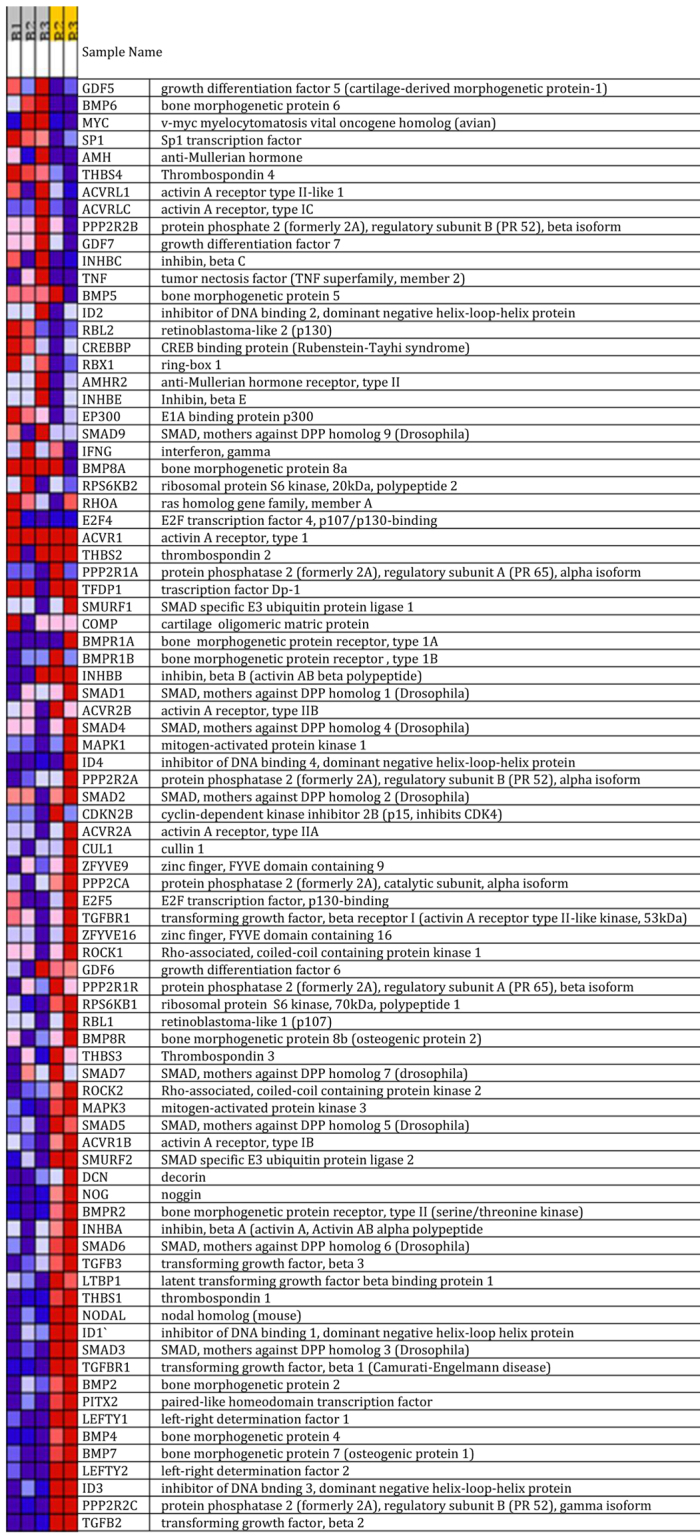

MKL2 regulates TGFβ signaling in embryonic stem cells

Microarray analyses were performed with mRNA harvested from undifferentiated Mkl2–/– embryonic stem (ES) cells and from the parental wild-type SV129 ES cell line. We chose to compare undifferentiated Mkl2–/– ES cells with control ES cells to identify MKL 2-regulated pathways that underlie basic developmental programs and to maximize signal-to-noise in the first stage of these analyses. These data were deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) public database (Accession Number GSE38316). In exploratory analyses, more genes were downregulated than upregulated in response to Mkl2 deletion, consistent with the function of MKL2 as a transcriptional co-activator (supplementary material Table S3). To screen for canonical molecular pathways regulated directly or indirectly by Mkl2 deletion, Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) was applied to the microarray data. Remarkably, no Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG)-defined molecular pathway was upregulated in Mkl2–/– ES cells compared with wild-type cells, whereas 55 KEGG-defined pathways showed evidence of repression (FDR q value<0.05; supplementary material Table S4). The most repressed pathway was TGFβ signaling, which showed substantial repression in multiple transcripts, including both TGFβ2 and TGFβ3 (FDR q value<0.0001) (Fig. 3). As shown in the heat map, TGFβ2 demonstrated the largest relative decrease in Mkl2–/– ES cells compared with wild-type ES cells (Fig. 3). qRT-PCR analysis confirmed an 84% reduction in undifferentiated TGFβ2 mRNA in Mkl2–/– ES cells compared with wild-type ES cells (supplementary material Fig. S3). Moreover, consistent with the microarray analysis, a 62% decrease in TGFβ3 mRNA was observed in Mkl2–/– ES cells (supplementary material Fig. S3). By contrast, a small, but statistically insignificant, difference was observed in TGFβ1 mRNA (supplementary material Fig. S3). However, expression of multiple other genes in the TGFβ signaling pathway was decreased in Mkl2–/– ES cells, including Tgfbr1, Smad3, Ltbp1, Tgfb3, Smad6, Smad5, Smad7, Smad2, Smad4 and Smad1 (Fig. 3). In addition, expression of multiple genes involved in the BMP signaling pathway were decreased in Mkl2–/– ES cells compared with the parental ES cell line, including Bmp7, Bmp4, Bmp2, Inhba, Bmpr2, Acvrib, Bmp8r, Acvr2a, Acvr2b, Inhbb, Bmpr1b and Bmpr1a (Fig. 3). These microarray findings were validated by qRT-PCR performed with mRNA harvested from Mkl2–/– ES cells and the parental ES cell line (supplementary material Fig. S3).

Fig. 3.

Microarray analysis reveals reduced expression of TGFβ signaling pathway genes in Mkl2–/– ES cells. Microarray analysis was performed with mRNA harvested from undifferentiated wild-type and Mkl2–/– ES cells. To screen for pathways affected by Mkl2 deletion, Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) was applied to identify KEGG-designated signaling pathways that are coordinately induced or repressed in response to Mkl2 deletion. The most repressed pathway was TGFβ signaling (FDR q value<0.0001). The heat map shown on the left displays the list of KEGG-designated genes in the TGFβ signaling pathway and their relative level of gene expression in biological replicate samples of Mkl2–/– (gray) and wild-type (yellow) ES cells. Red or blue signal indicates increased or decreased expression, respectively. Brightness is proportional to the difference from the median expression level. The NCBI gene identification names are listed on the right (see also Dünker and Krieglstein, 2002).

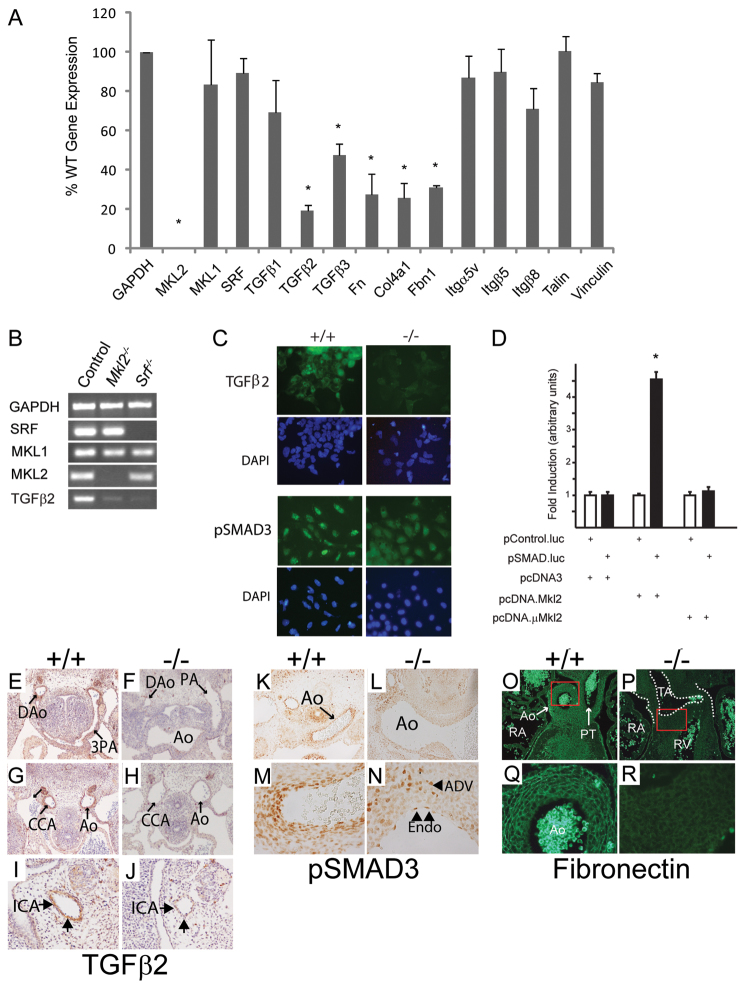

To determine whether TGFβ signaling was regulated during the differentiation of ES cells into cystic embryoid bodies, qRT-PCR was performed with mRNA harvested from Mkl2–/– and control ES cells after their differentiation into embryoid bodies (Fig. 4A). As anticipated, Mkl2 gene expression was below the limits of detection in Mkl2–/– ES cells, but the Mkl2 gene was expressed abundantly in wild-type ES cells (Fig. 4A,B) (P<0.01). No significant difference was observed in MKL1 and SRF mRNA in wild-type and Mkl2–/– ES cells (Fig. 4A,B). Once again, Tgfb2 gene expression was decreased by 84.0±3.4% in Mkl2–/– ES cell compared with control cells (Fig. 4A,B) (P<0.01). Of note, TGFβ2 mRNA was also reduced in differentiating Srf–/– ES cells (Fig. 4B). In addition, expression of TGFβ1 and TGFβ3 mRNA was reduced to 65.0±16.3% and 45.3±5.5%, respectively, in differentiating Mkl2–/– ES cells compared with control cells (Fig. 4A) (P<0.01). Moreover, TGFβ-regulated genes encoding extracellular matrix (ECM) were downregulated in differentiating Mkl2–/– ES cells. Fibronectin (Fn) exhibited a 77.3±10.1% decrease, type IV collagen α1 (Col4a1) exhibited a 78.5±7.4% decrease and fibrillin 1 (Fbn1) exhibited a 75.8±1.0% decrease compared with wild-type ES cells (Fig. 4A) (P<0.01). By contrast, integrins αV, β8 and β5, as well as the vinculin and talin genes were expressed at comparable levels in Mkl2–/– and wild-type ES cells (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

TGFβ signaling is downregulated in Mkl2–/– ES cells and the great arteries of Mkl2–/– embryos. (A) qRT-PCR analyses performed with mRNA harvested from wild-type and Mkl2–/– ES cells following 6 days of differentiation in vitro. The experiment was performed three times with three biological replicates used in each experiment. Data are expressed as the percentage of wild-type gene expression observed in Mkl2–/– ES cells±s.e.m. (*P<0.01 versus wild-type gene expression). (B) A representative ethidium bromide-stained agarose gel showing amplified RT-PCR products obtained with mRNA harvested from wild-type (control), Mkl2–/– and Srf–/– ES cells and PCR primers that amplify GAPDH, SRF, MKL1, MKL2 and TGFβ2 mRNA. (C) Photomicrograph showing differentiating wild-type (+/+) and Mkl2–/– (–/–) ES cells plated on fibronectin-coated plates immunostained with anti-TGFβ2 antibody (green stain), anti-phospho-SMAD3 (pSMAD3) antibody (green) or DAPI counterstain (blue nuclear stain). Original magnification was ×400. (D) Transient co-transfection analyses was performed with Mkl2–/– ES cells co-transfected with the pSMAD.luc reporter plasmid (black bars) or the pControl.luc plasmid (white bars) and expression plasmids encoding MKL2 (pcDNA.MKL2), a dominant-negative μMKL2 mutant protein (pcDNAμMKL2) or the negative control plasmid pcDNA3, respectively. Data are expressed as the fold induction in luciferase activity (arbitrary units) compared with luciferase activity observed in cells co-transfected with the pControl.luc reporter plasmid±s.e.m. (*P<0.001). (E-J) Transverse sections harvested from E12.5 wild-type (+/+) and Mkl2–/– (–/–) embryos immunostained with anti-TGFβ2 antibody (brown). The dorsal aorta (DAo), pharyngeal arch arteries (PA), aorta (Ao), common carotid artery (CCA) and internal carotid artery (ICA) are identified. Original magnifications were ×100 (E-H) and ×200 (I,J). Arrows in I,J indicate TGFβ2 expression. (K-N) Transverse sections showing the aortic arch (Ao) of E12.5 wild-type (K,M) and Mkl2–/– (L,N) embryos immunostained with anti-phospho-SMAD3 antibody (brown). (L,N) High-power magnification reveals abundant nuclear phospho-SMAD-3 in endothelial cells (Endo) and adventitial (ADV) cells of Mkl2–/–aorta, whereas pSMAD3 expression is markedly attenuated in medial SMCs. Original magnifications were ×100 (K,L) and ×400 (M,N). (O-R) Cardiac outflow tract of E14.5 wild-type (O,Q) and Mkl2–/– (P,R) embryos immunostained with anti-fibronectin antibody. The red rectangles in O and Q indicate the regions shown in P and R. Abundant fibronectin (green) is observed throughout the ascending aorta (Ao) and pulmonary trunk (PT) of the wild-type embryo (O,P). By contrast, expression of fibronectin is markedly attenuated throughout the mutant truncus arteriosus (TA) of the Mkl2–/– embryo (Q,R). RA, right atria; RV, right ventricle. Original magnifications were ×100 (I,K) and ×400 (J,L).

Consistent with these findings, abundant expression of TGFβ2 protein (green stain) was observed in differentiating wild-type ES cells, whereas TGFβ2 protein was not detected above background levels in Mkl2–/– ES cells (Fig. 4C). Moreover, TGFβ signaling, as assessed by the nuclear accumulation of phosphorylated Smad3, was dramatically downregulated in differentiating Mkl2–/– ES cells compared with wild-type ES cells (Fig. 4C). Co-transfection of Mkl2–/– ES cells with the pSMAD.luc luciferase reporter plasmid and an expression plasmid encoding mouse MKL2 revealed a 4.5-fold increase in luciferase reporter plasmid above levels observed in Mkl2–/– ES cells co-transfected with pSMAD.luc and pcDNA3 alone (P<0.01) (Fig. 4D). As anticipated, MKL2 failed to transactivate the negative control luciferase reporter plasmid pControl.luc and forced expression of the dominant-negative MKL2 mutant protein failed to transactivate the pSMAD.luc reporter plasmid (Fig. 4D). Taken together, these data demonstrate that MKL2 regulates TGFβ2 gene expression, TGFβ signaling and a subset of TGFβ responsive genes encoding ECM in ES cells.

Mkl2–/– mutants exhibit a block in TGFβ signaling in the embryonic vasculature

Consistent with previous reports (Molin et al., 2003), low, but detectable, levels of TGFβ3 (green stain) were observed in the cardiac outflow tract and great arteries at this stage of embryonic development (supplementary material Fig. S4A,B,E,F). At the level of sensitivity afforded by immunohistochemistry, no obvious difference in TGFβ1 or TGFβ3 expression was observed in the cardiac outflow tract and great arteries of Mkl2–/– embryos compared with wild-type littermates (supplementary material Fig. S4C,D,G,H). By contrast, abundant TGFβ2 (brown stain) was observed in the great arteries, including the right dorsal aorta (DAo), 3rd pharyngeal arch artery (3PA), common carotid artery (CCA), aorta (Ao) and internal carotid artery (ICA) of wild-type embryos (Fig. 4E,G,I). By contrast, TGFβ2 expression was markedly attenuated in the great arteries of Mkl2–/– embryos (Fig. 4F,H,J). Consistent with these observations, the nuclear accumulation of phosphorylated Smad3 (brown stain) was dramatically downregulated in the tunica media of the aorta (Ao) and great arteries in E13.5 Mkl2–/– mutant embryos (Fig. 4K-N; data not shown). By contrast, comparable levels of TGFβ2 were observed in intimal endothelial cells (End) and adventitial (ADV) cells in the control and mutant embryos (compare Fig. 4M,N). Moreover, fibronectin (green stain) was dramatically downregulated in the ascending aorta (Ao) and great arteries of E14.5 Mkl2–/– embryos compared with control littermates (Fig. 4O,P). In wild-type embryos, fibronectin is expressed throughout the media of the aorta (Ao) and pulmonary trunk (PT) (Fig. 4O,P). By contrast, very low levels of fibronectin were observed in the media of the mutant truncus arteriosus (TA) (Fig. 4Q,R). Taken together, these data demonstrate that, as in ES cells, TGFβ2 expression, TGFβ signaling and expression of the TGFβ-regulated gene fibronectin are downregulated in the great arteries of Mkl2–/– embryos.

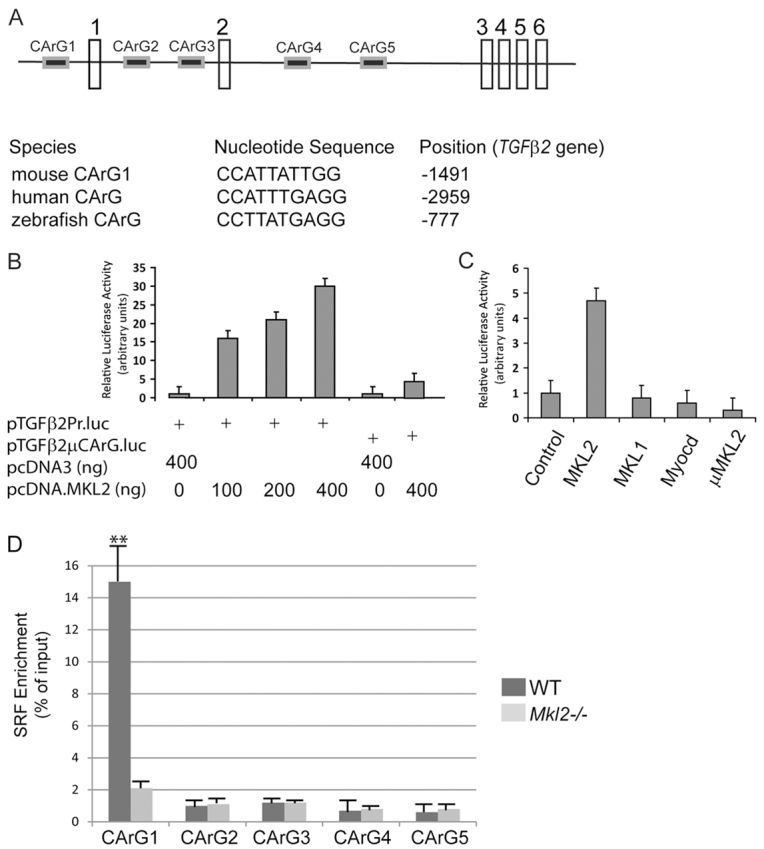

The TGFβ2 gene is a direct transcriptional target of MKL2

A bioinformatics search revealed five putative SRF-bindings sites, or CArG boxes, in the mouse TGFβ2 promoter and intron sequences, including a consensus CArG box at –1491 bp (Fig. 5A; data not shown). In addition, eight putative CArG boxes were identified within, or flanking, the human Tgfb2 gene (Fig. 5A; data not shown). Moreover, five CArG boxes (four consensus) were identified within, or flanking, the zebrafish Tgfb2 gene (Fig. 5A; data not shown). Transient co-transfection analyses of Cos-7 cells with increasing concentrations of an expression plasmid encoding mouse MKL2 (pcDNA.MKL2) and the pTGFβ2Pr.luc reporter plasmid, which is under the control of the 1.7-k murine TGFβ2 promoter, revealed a stepwise increase in luciferase activity up to 31-fold higher than levels observed when cells were co-transfected with pcDNA3 and pTGFβ2Pr.luc (Fig. 5B). By contrast, a fivefold increase in luciferase activity was observed when Cos-7 cells were co-transfected with pcDNA.MKL2 and the pTGFβ2 μCARG.luc reporter plasmid, indicating that most, but not all, MKL2-mediated transcriptional activity is dependent upon CArG box 1 in the TGFβ2 promoter (Fig. 5B). In addition, forced expression of MKL2 in Cos-7 cells transactivated the TGFβ2 promoter 4.7-fold higher than levels observed in cells co-transfected with the pcDNA3 control expression plasmid (Fig. 5C). Surprisingly, however, co-transfection with expression plasmids encoding MKL1 or myocardin failed to increase luciferase activities above levels observed when cells were co-transfected with pcDNA3 (Fig. 5C). As anticipated, forced expression of the dominant-negative MKL2 mutant protein did not transactivate the TGFβ2 promoter (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

The TGFβ2 promoter is activated by an Mkl2/Srf protein complex. (A) Schematic representation of the mouse Tgfb2 gene showing location of the five CArG boxes (CArG1-5). The nucleotide sequence of CArG boxes identified in the mouse, human and zebrafish TGFβ2 promoters are shown. (B) Cos-7 cells were co-transfected with 400 ng (+) of the pTGFβ2Pr.luc reporter plasmid or the pTGFβ2 μCArG.luc reporter plasmid and the indicated amount (ng) of the pcDNA.Mkl2 expression plasmid encoding mouse MKL2. Data are expressed as relative luciferase activity (arbitrary units) compared with cells co-transfected with the control expression plasmid pcDNA3±s.e.m. (C) Cos-7 cells were co-transfected with pTGFβ2Pr.luc and expression plasmids encoding mouse MKL2, MKL1, myocardin and dominant-negative MKL2 mutant protein. Data are expressed as relative luciferase activity (arbitrary units) compared with cells co-transfected with pTGFβ2Pr.luc and pcDNA3±s.e.m. (D) Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analyses performed with chromatin harvested from wild-type (dark-gray bars) and Mkl2–/– (light-gray bars) ES cells. Chromatin was immunoprecipitated with anti-SRF antibody and qPCR was performed with PCR primers that selectively amplify genomic DNA spanning CArG boxes 1-5, respectively, of the Tgfb2 gene. Immunoprecipitated DNA was normalized to input DNA. Data are expressed as the mean SRF enrichment (% of input)±s.e.m. (n=4). **P<0.01.

Next, to determine whether an MKL2/SRF protein complex binds directly to one or more of the CArG boxes in the mouse Tgfb2 gene in vivo, chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analyses were performed (Fig. 5D). Remarkably, 15-fold enrichment of immunoprecipitated, amplified SRF bound to CArG box 1 (CArG1) DNA was observed in wild-type ES cells (P<0.01) (Fig. 5D, dark gray bars). By contrast, in Mkl2–/– ES cells (Fig. 5D, light gray bars), only a two-fold increase in SRF bound to CArG box 1 was observed, demonstrating that binding of SRF to CArG box1 is dependent upon MKL2. Surprisingly, however, a less than two-fold enrichment of immunoprecipitated SRF bound to DNA was observed with PCR primers flanking CArG boxes 2-5, respectively, in wild-type and Mkl2–/– ES cells: a difference which was not statistically significant (Fig. 5D). Taken together, these data demonstrate that transcription of the Tgfb2 gene is activated via binding of an MKL2/SRF protein complex to CArG box 1 of the mouse TGFβ2 promoter.

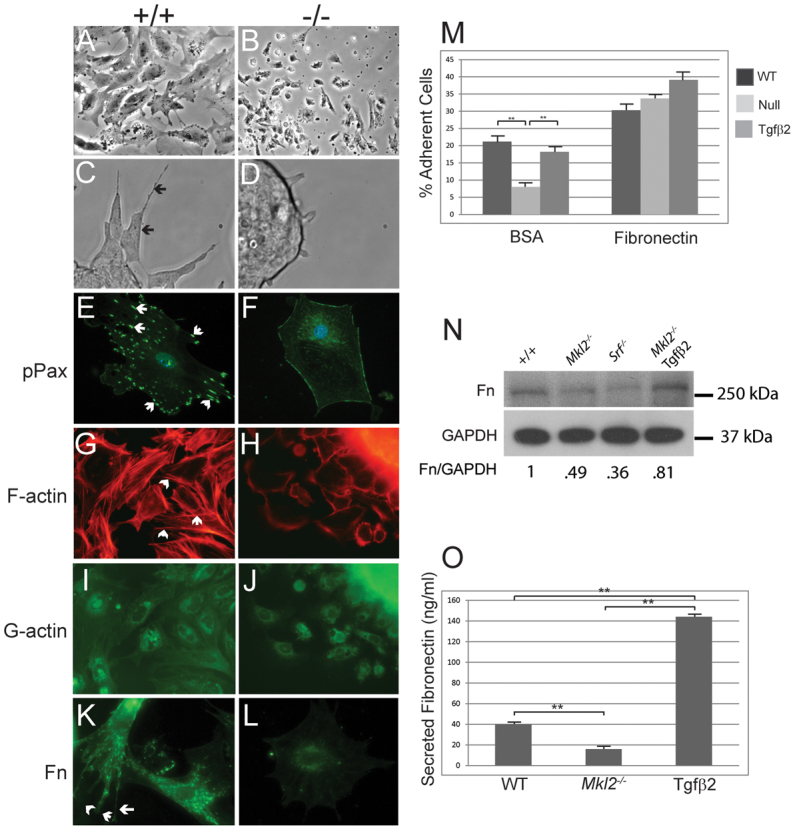

Mkl2–/– ES cells exhibit defects in cytoskeletal organization and cell adhesion

Attempts to grow Mkl2–/– ES cells were hindered because the cells failed to adhere to uncoated tissue culture plates. To overcome this problem, Mkl2–/– ES cells were grown on plates coated with fibronectin. Phase-contrast microscopy revealed that, as they differentiate, wild-type ES cells adhere to fibronectin matrix, and spread and form numerous protrusive lamellpodia and filopodia (Fig. 6A,C, arrows). By contrast, the Mkl2–/– ES cells exhibited obvious defects in cell adhesion, maintaining a rounded appearance with rare protrusions (Fig. 6B,D). To better characterize cell morphology and adhesion, differentiating control and Mkl2–/– ES cells were plated on collagen and immunostained with a panel of antibodies that recognize proteins involved in cytoskeletal organization and cell adhesion (Fig. 6E-L). Six days after plating, wild-type ES cells located on the margins of embryoid bodies spread and begin to migrate, demonstrating numerous lamellopodia and filopodia (Fig. 6A,C,E). By contrast, Mkl2–/– ES cells assumed a polygonal shape that rarely demonstrated lamellopodia or filopodia (Fig. 6B,D,F). Paxillin (pPax) (green stain), a component of focal adhesions, was observed in discrete complexes across the surface of wild-type ES cells (Fig. 6E, arrows). By contrast, relatively low levels of dot-like phosphorylated paxillin complexes were observed on the margins of Mkl2–/– ES cells (Fig. 6F). Wild-type ES cells exhibited dense F-actin networks (red stain) throughout their cytoplasm and at the leading edge of lamellopodium (Fig. 6G, arrows). By contrast, centrally located dot-like focal adhesions that are indicative of a less-motile cell were visualized in Mkl2–/– ES cells (Fig. 6H). DNase I staining revealed comparable expression of G-actin (green stain) in wild-type and Mkl2–/– ES cells, strongly suggesting that the F:G actin ratio is decreased in Mkl2–/– ES cells (Fig. 6I,J). Finally, discrete complexes containing fibronectin (Fn) were observed in wild-type ES cells, often localizing to lamellpodia and filopodia (Fig. 6K, arrows). By contrast, very low levels of fibronectin were observed in the perinuclear region of Mkl2–/– ES cells (Fig. 6L).

Fig. 6.

Mkl2–/– ES cells exhibit derangements in cytoskeletal organization and cell adhesion that are rescued by TGFβ2. (A-D) Phase-contrast micrographs showing wild-type (A,C) and Mkl2–/– (B,D) ES cells 24 hours after plating on fibronectin-coated chamber slides. Wild-type ES cells spread and form numerous protrusive lamellpodia and filopodia (arrows) (C). Original magnifications were ×20 (A,B) and ×200 (C,D). (E-L) Immunostaining of wild-type and Mkl2–/– ES cells for expression of proteins associated with cell adhesion and cytoskeletal organization. (E,F) Wild-type and Mkl2–/– ES cells immunostained with anti-phospho-paxillin (green) and counterstained with DAPI (blue), demonstrating abundant expression in complexes across wild-type ES cells and low level expression at margins of Mkl2–/– ES cell. Arrows indicate focal adhesions. (G,H) Staining with rhodamine-phalloidin, which localizes to F-actin (red), demonstrates a rich array of actin filaments in control ES cells and absence of stress fibers in Mkl2–/– ES cells. Arrows indicate actin filaments. (I,J) ES cells were exposed to DNase I to identify monomeric G-actin (green). (K,L) ES cells immunostained with anti-fibronectin antibody demonstrate abundant expression in wild-type ES cells with localization to lamellopodia and filopodia (K, white arrows). By contrast, relatively low levels of fibronectin are observed in the perinuclear regions of Mkl2–/– ES cells (L). Original magnification ×400. (M) A fluorometric cell adhesion assay was performed comparing the capacity of wild-type (WT) ES cells (black bars), Mkl2–/– null ES cells (light-gray bars) and Mkl2–/– null ES cells stably transfected with an expression plasmid encoding TGFβ2 (gray bars) to adhere to BSA- or fibronectin-coated tissue culture plates. Data are expressed as % adherent cells±s.e.m. (**P<0.01). (N) Immunoblot analysis of fibronectin (Fn) expression in cell lysates prepared from wild-type (+/+) Mkl2–/–, Srf–/– and Mkl2–/– + TGFβ2 ES cells, respectively. The fibronectin signal was normalized to expression of GAPDH (bottom panel). Data are expressed as normalized Fn expression compared with Fn expression in wild-type ES cells. MW standards are shown on the right of the blot. (O) An ELISA assay was employed to quantify secreted fibronectin in medium harvested from wild-type, Mkl2–/– and Mkl2–/– + TGFβ2 ES cells after 1 hour of incubation. Data are expressed as mean secreted fibronectin (ng/ml)±s.e.m. **P<0.001.

A quantitative fluorescence-based cell adhesion assay demonstrated that Mkl2–/– ES cells exhibit profound defects in cell adhesion to bovine serum albumin (BSA)-coated tissue culture plates. After 1 hour of incubation, 21.2±3.1% of wild-type (WT) cells adhere to the uncoated plates, whereas only 8.0±1.8% of Mkl2–/– ES cells adhere (P<0.001) (Fig. 6M). By contrast, 30.4±3.2% of wild-type ES cells and 33.7±1.9% of Mkl2–/– ES cells adhere to fibronectin-coated tissue culture plates, a difference that is not statistically significant (Fig. 6M). This suggested that the adhesive defects observed in Mkl2–/– ES cells were caused, at least in part, by a block in TGFβ2-induced expression of fibronectin. Consistent with this hypothesis, forced expression of TGFβ2 in Mkl2–/– ES cells restored the capacity of Mkl2–/– ES cells to adhere to BSA-coated tissue culture plates (8.0±1.8% versus 18.2±3.1%; P<0.001) (Fig. 6M). Of note, forced expression of TGFβ2 in Mkl2–/– ES cells enhanced the capacity of these cells to adhere to fibronectin-coated plates even beyond the capacity of wild-type ES cells (39.2±2.6% versus 30.4±3.4%; P<0.05).

To confirm that TGFβ2 did indeed induce expression of fibronectin in Mkl2–/– ES cells, two complementary assays were employed. Immunoblot analysis revealed a 51% decrease in expression of cellular fibronectin protein in Mkl2–/– ES cells compared with control cells (Fig. 6N). Similarly, Srf–/– ES cells exhibit a 63% decrease in expression of cellular fibronectin compared with wild-type ES cells (Fig. 6N). However, in Mkl2–/– ES cells stably transduced with an expression plasmid encoding TGFβ2, expression of cellular fibronectin was restored to levels approaching those observed in wild-type ES cells (Fig. 6N). Consistent with these findings, a quantitative radioimmunoassay revealed a 60% decrease in secreted fibronectin in the media of Mkl2–/– ES cells (16.2±0.5 ng/ml) compared with wild-type ES cells (40.5±1.0 ng/ml) (P<0.001) (Fig. 6O). Once again, forced expression of TGFβ2 in Mkl2–/– ES cells led to enhanced secretion of fibronectin (144.4±1.0 ng/ml) above levels observed in the media of wild-type ES cells (P<0.001) (Fig. 6O). Taken together, these data demonstrate that MKL2 activates transcription of the Tgfb2 gene, which in turn activates expression of genes encoding TGFβ-regulated genes, including fibronectin, influencing the adhesive properties of the cell.

DISCUSSION

Transcriptional co-activators play crucial roles transducing signals that expand information encoded within the genome during embryonic development and in response to environmental cues and signals. Our group and others have reported that Mkl2 loss-of-function mutant embryos exhibit defects in vascular patterning attributable to a cell-autonomous block in differentiation of neural crest-derived vascular SMCs (Li et al., 2005; Oh et al., 2005; Wei et al., 2007). However, this defect fails to explain the lethality in Mkl2–/– embryos that occurs between E13.5 and E15.5. The studies described in this report demonstrate that Mkl2–/– embryos exhibit hemorrhage caused by aneurysmal dilation and dissection of select arterial beds throughout the embryo. Surprisingly, microarray studies and qRT-PCR experiments identified a conserved MKL2-regulated TGFβ signaling pathway in ES cells. Moreover, Mkl2–/– ES cells exhibit profound defects in cell adhesion that are rescued by forced expression of TGFβ2. Consistent with this observation, TGFβ2 expression, TGFβ signaling and TGFβ-regulated genes encoding key components of the ECM are downregulated in the developing vasculature of Mkl2–/– embryos.

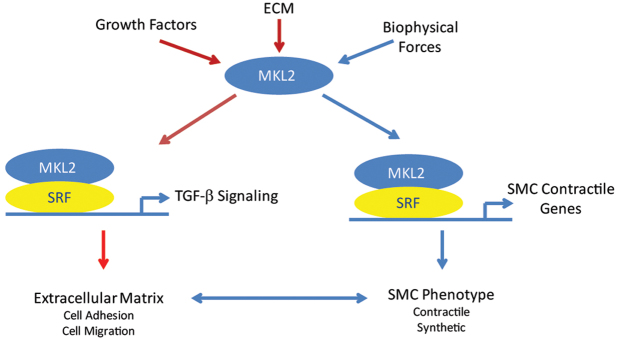

The identification of an MKL2/TGFβ signaling pathway provides important new insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying MKL2/SRF function in the embryonic vasculature. As reported previously, an SRF/MKL2 complex plays a crucial role in activating a subset of SRF-dependent genes that encode SMC contractile proteins in neural crest-derived vascular SMCs (Li et al., 2005; Oh et al., 2005; Wei et al., 2007). Indeed, expression of SM-α-actin and SM-MyHC is severely attenuated in vascular SMCs populating the aorta and pharyngeal arch arteries in E12.5 Mkl2–/– embryos compared with wild-type (WT) littermates (supplementary material Fig. S5A-H). Surprisingly, in Mkl2–/– embryos expression of SM-MyHC and SM-α-actin is also dramatically downregulated in a subset of non-neural crest-derived vascular SMCs, including those populating the mutant basilar artery (supplementary material Fig. S5I,J) and hepatic vasculature (J.L., unpublished observations). These findings demonstrate that the role of MKL2 in the vasculature is not restricted to cardiac neural crest-derived SMCs. This raises the crucial issue of whether defects in vascular patterning and stabilization in the embryo resulted primarily from an MKL2-mediated block in expression of genes encoding contractile SMC proteins versus a block in TGFβ signaling. Indeed, mutations of the ACTA2 gene are associated with familial thoracic aneurysms in humans (Guo et al., 2007; Morisaki et al., 2009; Regalado et al., 2011). However, it is noteworthy that conditional ablation of the myocardin (Myocd) gene in cardiac neural crest-derived SMCs results in dramatic suppression of the SMC contractile proteins that was not accompanied by vascular aneurysm, dissection or hemorrhage (Huang et al., 2008). Ultimately, as discussed below and shown in Fig. 7, we believe that MKL2/SRF-mediated loss of SMC contractile proteins in Mkl2–/– embryos directly contributes to the vascular phenotype observed in Mkl2–/– embryos and the loss of SMC contractile proteins indirectly influences TGFβ signaling in the vasculature. Conversely, TGFβ signaling, in turn, directly and indirectly influences the contractile SMC gene program. This model highlights the crucial role that the transcriptional co-activator MKL2 plays in regulating angiogenesis and vascular patterning in the embryo.

Fig. 7.

An MKL2/TGFβ signaling pathway is required for vascular patterning and stabilization of the great arteries during embryonic development. The transcriptional co-activator MKL2 transduces multiple signals in vascular SMCs that promote translocation of MKL2 (bound to G-actin) to the nucleus, where it physically associates with SRF. This, in turn, promotes SRF binding to CArG boxes, which activates transcription of the Tgfb2 gene and other genes encoding TGFβ signaling molecules. Activation of TGFβ signaling activates expression genes that encode key components of the ECM, including fibronectin, fibrillin and Col4a1. The ECM, in turn, feeds back on vascular SMCs, reinforcing the contractile SMC phenotype and leading to organization of the tunica media that is required for stabilization of the great arteries. In addition, MKL2 promotes SMC differentiation of the great arteries via binding to SRF, which in turn binds to CArG boxes that control expression of genes encoding SMC contractile proteins. Expression of SMC contractile proteins influences expression of TGFβ signaling and TGFβ-regulated genes encoding ECM, and visa versa, serving to define an MKL2/SRF molecular program required for vascular development and patterning in the embryo. Pathways identified in the experiments described in this work are shown in red.

The data provided in this report expands our understanding of the function of MKL2 in the embryo by revealing that MKL2 lies upstream in a transcriptional program that regulates TGFβ expression, TGFβ signaling and TGFβ-regulated genes encoding ECM. Surprisingly, we observed that MKL2 profoundly influences the morphology and adhesive properties of ES cells that act at least in part via TGFβ/BMP signaling. As shown in Fig. 7, in the embryonic vasculature, developmental cues and extracellular signals transduced via RhoA and cytoskeletal actin promote the translocation of G-actin/MKL2 complexes from the cytoplasm to the SMC nucleus (Mouilleron et al., 2011). In the nucleus, MKL2 physically associates with SRF, which promotes the binding of the MKL2/SRF complex to the TGFβ2 promoter (and related TGFβ family members), activating TGFβ signaling in the arterial wall. TGFβ signaling, in turn, activates expression of a subset of genes encoding ECM, including fibronectin (Fbn), fibrillin 1 (Fbn1) and Col4a1 (Col4a1). The ECM feeds back upon the vascular SMC, modulating its structure, morphology, adhesive and migratory properties (Astrof and Hynes, 2009; Pardali et al., 2010). These new data support a model wherein the loss of MKL2 results in a block in TGFβ signaling in select arterial beds, including the great arteries, causing alterations in cell adhesion with disruption of the tunica media, which ultimately leads to aneurysmal dilation and hemorrhage. Consistent with this model, in E10.5 EIIIA/EIIIB fibronectin-double null embryos defective association of vascular SMCs with the endothelium of the aorta is observed. Interestingly, in fibronectin mutant embryos, vascular SMCs assume a rounded morphology resembling that observed in Mkl2–/– mutant embryos (Astrof et al., 2007). As such, these new data serve to identify a second arm (shown in red) of the MKL2 signaling pathway that plays a crucial role in regulating angiogenesis and vascular stabilization required for embryonic survival (Fig. 7).

Other data supporting this model include the overlapping patterns of MKL2 and TGFβ2 expression in the embryonic vasculature. Fate-mapping studies have shown that, in the E8.0 mouse embryo, MKL2 mRNA is observed in cardiac neural crest cells located in the hindbrain prior to their migration to the cardiac outflow tract and great arteries and MKL2 is expressed abundantly in these arteries throughout development (Li et al., 2005). Similarly, TGFβ2 is the predominant TGFβ isoform expressed in the great arteries and the gene is expressed abundantly in SMCs populating the aortic sac and pharyngeal arch arteries in a temporal window consistent with MKL2-induced activation of the Tgfb2 gene (Molin et al., 2003). Therefore, it is not surprising that Mkl2–/– and Tgfb2–/– embryos exhibit vascular defects that are attributable, at least in part, to a block of TGFβ signaling in aortic sac and the 4th pharyngeal arch artery, which gives rise to the aortic arch. Consistent with this observation, abundant nuclear Smad2 expression is observed in the 4th pharyngeal arch segment of the aortic arch, but not in other pharyngeal arch segments or the ascending or descending aorta (Molin et al., 2004). Similarly, fibronectin, a TGFβ target gene that is dramatically downregulated in Mkl2–/– ES cells and arteries, is expressed abundantly in the aortic sac and pharyngeal arch arteries. Therefore, vulnerability of the aorta and fourth pharyngeal arch arteries may be linked to a localized reduced vascular Smad2/3 signaling and related expression of fibronectin in Mkl2–/– embryos. The findings that TGFβ2, the predominant TGF-β isoform expressed in the cardiac outflow tract and great arteries in the embryo, as well as SMAD signaling and fibronectin are dramatically downregulated in the great arteries of Mkl2–/– embryos is consistent with this model. Taken together, these data support the conclusion that the vascular pathology observed in Mkl2–/– embryos results from a block in MKL2-induced expression of TGFβ2 (and probably TGFβ3) and TGFβ signaling in the developing arterial wall, reflecting the crucial role that SRF and MKL2 play in development of the aorta and great arteries in the embryo.

This raises the important question of how does the block in TGFβ signaling observed in ES cells relate to the vascular phenotype observed in Mkl2–/– mutant embryos? Remarkably, multiple genes encoding TGFβ/BMP signaling molecules were downregulated in undifferentiated Mkl2–/– ES cells (Fig. 3; Fig. 4A and supplementary material Fig. S3). Some, but not all, of these genes are expressed in the developing vasculature. In this regard, it is noteworthy that MKL1 and MKL2 are expressed in undifferentiated ES cells, whereas myocardin is expressed several days after the initiation of differentiation in vitro. Nevertheless, the demonstrated block in multiple genes encoding TGFβ/BMP family members in Mkl2–/– ES cells reveals a non-redundant function for MKL2 in ES cells in this context. Similarly, even though myocardin, MKL1 and MKL2 are co-expressed in vascular SMCs, only Mkl2–/– embryos demonstrate a block in TGFβ signaling in the embryonic vasculature, revealing a unique and non-redundant function of MKL2 in select arteries and vascular beds. However, it remains possible, indeed likely, that other TGF-β/BMP signaling molecules contributed to the vascular phenotype observed in Mkl2–/– mutant embryos. In support of this hypothesis, Tgfb2–/– embryos exhibit defects in pharyngeal arch development, but fail to phenocopy Mkl2–/– embryos (Gittenberger-de Groot et al., 2006; Sanford et al., 1997). By contrast, Tgfb2/Tgfb3 compound mutant embryos recapitulate multiple aspects of the vascular changes observed in Mkl2–/– embryos (Dünker and Krieglstein, 2002).

Previous studies have shown that TGFβ2 and its cognate receptors, TGFBR2 and TGFBR1/ALK5, play a crucial role in embryonic angiogenesis and cardiovascular development (for a review, see Pardali et al., 2010). Both Mkl2 and Tgfb2 knockout mice exhibit aortic arch malformations involving the 4th pharyngeal arch artery (Gittenberger-de Groot et al., 2006; Sanford et al., 1997). However, Mkl2–/– embryos exhibit aneurysmal dilation of the aortic arch and carotid arteries, whereas Tgfb2–/–embryos exhibit defects in vascular patterning attributable to the 4th pharyngeal arch artery. What explains these differences? As a transcriptional co-activator, MKL2 regulates and coordinates expression of multiple SRF-dependent genes involved in angiogenesis. Indeed, TGFβ2 and TGFβ3 are expressed in the great arteries during embryonic development (supplementary material Fig. S4A-L) and both isoforms were markedly repressed in Mkl2–/– ES cells (Fig. 3A; supplementary material Fig. S3). Moreover, expression of genes encoding TGFβ receptors and multiple Smads were downregulated in Mkl2–/– ES cells (Fig. 3; supplementary material Fig. S3). As such, the observed differences in phenotype between Mkl2–/– and Tgfb2–/– embryos most probably result from the differential expression of SRF/MKL2-regulated genes beyond TGFβ2. As discussed above, these include both genes encoding SMC contractile proteins, as well as related TGFβ/BMP signaling molecules.

The observation that Mkl2–/– mutant embryos develop aortic aneurysms accompanied by downregulation of TGFβ isoforms, TGFβ signaling and TGFβ-regulated genes encoding ECM strongly supports a model wherein loss of function of TGFβ signaling in the vasculature leads to aneurysm formation during embryonic angiogenesis. Consistent with this observation, conditional ablation of the Tgfbr2 gene in vascular SMCs recapitulated many of the features observed in Mkl2–/– embryos, including aneurysmal dilation and dissection of the aorta during late embryonic development (Choudhary et al., 2009). However, these conclusions conflict with the observation that individuals with Marfan syndrome and Loeys-Dietz syndrome exhibit activation of TGFβ signaling and gain of TGFβ function in the arterial wall (Pearson et al., 2008). Interestingly, however, the NHLBI Go Exome Sequencing Project recently described a loss-of-function mutation in TGFB2 that is associated with familial thoracic aortic aneurysms and acute aortic dissections associated with mild system features of Marfan syndrome (Boileau et al., 2012). These data highlight gaps in current understanding of the role that TGFβ signaling plays in the embryonic and adult vasculature, and suggests that TGFβ signals are differentially transduced during embryonic and postnatal development. In any case, further studies examining the role of MKL2 and/or MKL1 in maintenance and adaptation of the adult vasculature to hemodynamic stress promise to provide important new insights into the pathogenesis of heritable and acquired forms of vascular disease involving aneurysm formation and dissection.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Jon Epstein, Mark Kahn and Ed Morrisey for their advice and helpful comments.

Footnotes

Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) [R01-HL102968 and R01-HL094520 to M.S.P., T32-HL0783 to N.B.] and by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania [to the University of Pennsylvania Cardiovascular Institute]. Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Competing interests statement

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material available online at http://dev.biologists.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1242/dev.082222/-/DC1

References

- Astrof S., Hynes R. O. (2009). Fibronectins in vascular morphogenesis. Angiogenesis 12, 165–175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astrof S., Crowley D., Hynes R. O. (2007). Multiple cardiovascular defects caused by the absence of alternatively spliced segments of fibronectin. Dev. Biol. 311, 11–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boileau C., Guo D. C., Hanna N., Regalado E. S., Detaint D., Gong L., Varret M., Prakash S. K., Li A. H., d’Indy H., et al. ; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Go Exome Sequencing Project (2012). TGFB2 mutations cause familial thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissections associated with mild systemic features of Marfan syndrome. Nat. Genet. doi:10.1038/ng.2348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary B., Zhou J., Li P., Thomas S., Kaartinen V., Sucov H. M. (2009). Absence of TGFbeta signaling in embryonic vascular smooth muscle leads to reduced lysyl oxidase expression, impaired elastogenesis, and aneurysm. Genesis 47, 115–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du K. L., Ip H. S., Li J., Chen M., Dandre F., Yu W., Lu M. M., Owens G. K., Parmacek M. S. (2003). Myocardin is a critical serum response factor cofactor in the transcriptional program regulating smooth muscle cell differentiation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 2425–2437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du K. L., Chen M., Li J., Lepore J. J., Mericko P., Parmacek M. S. (2004). Megakaryoblastic leukemia factor-1 transduces cytoskeletal signals and induces smooth muscle cell differentiation from undifferentiated embryonic stem cells. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 17578–17586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dünker N., Krieglstein K. (2002). Tgfbeta2 –/– Tgfbeta3 –/– double knockout mice display severe midline fusion defects and early embryonic lethality. Anat. Embryol. (Berl.) 206, 73–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gittenberger-de Groot A. C., Azhar M., Molin D. G. (2006). Transforming growth factor beta-SMAD2 signaling and aortic arch development. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 16, 1–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo D. C., Pannu H., Tran-Fadulu V., Papke C. L., Yu R. K., Avidan N., Bourgeois S., Estrera A. L., Safi H. J., Sparks E., et al. (2007). Mutations in smooth muscle α-actin (ACTA2) lead to thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissections. Nat. Genet. 39, 1488–1493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward I. P., Bridle K. R., Campbell G. R., Underwood P. A., Campbell J. H. (1995). Effect of extracellular matrix proteins on vascular smooth muscle cell phenotype. Cell Biol. Int. 19, 839–846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J., Cheng L., Li J., Chen M., Zhou D., Lu M. M., Proweller A., Epstein J. A., Parmacek M. S. (2008). Myocardin regulates expression of contractile genes in smooth muscle cells and is required for closure of the ductus arteriosus in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 118, 515–525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee E. C., Yu D., Martinez de Velasco J., Tessarollo L., Swing D. A., Court D. L., Jenkins N. A., Copeland N. G. (2001). A highly efficient Escherichia coli-based chromosome engineering system adapted for recombinogenic targeting and subcloning of BAC DNA. Genomics 73, 56–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Zhu X., Chen M., Cheng L., Zhou D., Lu M. M., Du K., Epstein J. A., Parmacek M. S. (2005). Myocardin-related transcription factor B is required in cardiac neural crest for smooth muscle differentiation and cardiovascular development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 8916–8921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massagué J. (1990). The transforming growth factor-beta family. Annu. Rev. CellBiol. 6, 597–641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molin D. G., Bartram U., Van der Heiden K., Van Iperen L., Speer C. P., Hierck B. P., Poelmann R. E., Gittenberger-de-Groot A. C. (2003). Expression patterns of Tgfbeta1-3 associate with myocardialisation of the outflow tract and the development of the epicardium and the fibrous heart skeleton. Dev. Dyn. 227, 431–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molin D. G., Poelmann R. E., DeRuiter M. C., Azhar M., Doetschman T., Gittenberger-de Groot A. C. (2004). Transforming growth factor β-SMAD2 signaling regulates aortic arch innervation and development. Circ. Res. 95, 1109–1117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morisaki H., Akutsu K., Ogino H., Kondo N., Yamanaka I., Tsutsumi Y., Yoshimuta T., Okajima T., Matsuda H., Minatoya K., et al. (2009). Mutation of ACTA2 gene as an important cause of familial and nonfamilial nonsyndromatic thoracic aortic aneurysm and/or dissection (TAAD). Hum. Mutat. 30, 1406–1411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrisey E. E., Tang Z., Sigrist K., Lu M. M., Jiang F., Ip H. S., Parmacek M. S. (1998). GATA6 regulates HNF4 and is required for differentiation of visceral endoderm in the mouse embryo. Genes Dev. 12, 3579–3590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouilleron S., Langer C. A., Guettler S., McDonald N. Q., Treisman R. (2011). Structure of a pentavalent G-actin*MRTF-A complex reveals how G-actin controls nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of a transcriptional coactivator. Sci. Signal. 4, ra40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh J., Richardson J. A., Olson E. N. (2005). Requirement of myocardin-related transcription factor-B for remodeling of branchial arch arteries and smooth muscle differentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 15122–15127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens G. K. (1998). Molecular control of vascular smooth muscle cell differentiation. Acta Physiol. Scand. 164, 623–635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens G. K., Kumar M. S., Wamhoff B. R. (2004). Molecular regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell differentiation in development and disease. Physiol. Rev. 84, 767–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardali E., Goumans M.-J., ten Dijke P. (2010). Signaling by members of the TGF-β family in vascular morphogenesis and disease. Trends Cell Biol. 20, 556–567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parmacek M. S. (2007). Myocardin-related transcription factors: critical coactivators regulating cardiovascular development and adaptation. Circ. Res. 100, 633–644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson G. D., Devereux R., Loeys B., Maslen C., Milewicz D., Pyeritz R., Ramirez F., Rifkin D., Sakai L., Svensson L., et al. ; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and National Marfan Foundation Working Group (2008). Report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and National Marfan Foundation Working Group on research in Marfan syndrome and related disorders. Circulation 118, 785–791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raines E. W. (2000). The extracellular matrix can regulate vascular cell migration, proliferation, and survival: relationships to vascular disease. Int. J. Exp. Pathol. 81, 173–182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regalado E., Medrek S., Tran-Fadulu V., Guo D. C., Pannu H., Golabbakhsh H., Smart S., Chen J. H., Shete S., Kim D. H., et al. (2011). Autosomal dominant inheritance of a predisposition to thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissections and intracranial saccular aneurysms. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 155, 2125–2130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanford L. P., Ormsby I., Gittenberger-de Groot A. C., Sariola H., Friedman R., Boivin G. P., Cardell E. L., Doetschman T. (1997). TGFbeta2 knockout mice have multiple developmental defects that are non-overlapping with other TGFbeta knockout phenotypes. Development 124, 2659–2670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotiropoulos A., Gineitis D., Copeland J., Treisman R. (1999). Signal-regulated activation of serum response factor is mediated by changes in actin dynamics. Cell 98, 159–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian A., Tamayo P., Mootha V. K., Mukherjee S., Ebert B. L., Gillette M. A., Paulovich A., Pomeroy S. L., Golub T. R., Lander E. S., et al. (2005). Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 15545–15550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thyberg J., Hultgårdh-Nilsson A. (1994). Fibronectin and the basement membrane components laminin and collagen type IV influence the phenotypic properties of subcultured rat aortic smooth muscle cells differently. Cell Tissue Res. 276, 263–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D. Z., Li S., Hockemeyer D., Sutherland L., Wang Z., Schratt G., Richardson J. A., Nordheim A., Olson E. N. (2002). Potentiation of serum response factor activity by a family of myocardin-related transcription factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 14855–14860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei K., Che N., Chen F. (2007). Myocardin-related transcription factor B is required for normal mouse vascular development and smooth muscle gene expression. Dev. Dyn. 236, 416–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.