Abstract

The negative effects on health by behavior such as cigarette smoking, lack of physical exercise, non-control of body weight and non-use of seat belts were empirically documented. Available findings of the various studies on lifestyle of the Saudi Arabian community were not encouraging. If the general health status of the Saudi population is to be improved, an enforcement of healthy lifestyles must be considered.

Keywords: Health promotion, Lifestyle, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

“Prevention is better than cure” is an often-quoted axiom. Recently, there was significant development with the enforcement of prevention as a means of avoiding disease and a movement towards positive health. The behaviour of the individuals is intimately related to their health status. This relationship will be scientifically discussed in this paper.

CIGARETTE SMOKING

In the USA, where more than one quarter of all adults smoke cigarettes,1 tobacco smoking is considered the leading preventable cause of disease, disability and premature death.2,3 It has been estimated that direct and indirect economic losses attributed to tobacco use in USA approach 85 billion US Dollars annually.2 The risk of premature death in smokers was about double that of non-smokers and was directly proportional to the frequency of smoking.2,4 Recent data showed that 15% of all cancer cases in the world were estimated to be due to cigarette smoking.5 Moreover, slightly less than 20% of all deaths in industrialized countries were attributable to tobacco.6,7

Tobacco contains about 4000 substances, more than 40 of which are carcinogenic and many others that are hazardous to cardiopulmonary systems.2 Many studies have demonstrated an association between cigarette smoking and cancers of the oral cavity, pharynx, larynx, lungs, esophagus, stomach, colon, rectum, pancreas, kidney and urinary bladder,3,5,8–11 and a less strong association with leukemia and cervical cancer.8 A causal association was found to exist between smoking and coronary artery disease, peptic ulcer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and stroke.3,10,12,13

Cigarette smoking is not only harmful to those using it deliberately, but also to involuntary smokers (the so-called “passive smokers”). Passive smoking is associated with coronary artery disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, leukemia and cancers of the lung, sinuses, cervix, breast and brain.1,2,14–16 In children, passive smoking is associated with higher incidence of asthma attacks, pneumonia, ear disease, sudden infant death syndrome and upper and lower respiratory tract infections.1,2,14,17 Fetuses are not exempted from hazards of smoking. It was found that pregnant mothers exposed to passive smoking were more prone to have low birth weight infants.18

It is doubtful that an ex-smoker will fully resume his pre-smoking health state. However, a substantial risk reduction with great improvement in life expectancy and quality is beyond doubt2,11,19–23 The benefit of quitting is documented even for old patients and those with an established tobacco-related disease.23–25

LACK OF PHYSICAL EXERCISE

More than half of Americans are considered to have a sedentary life-style.3 This is considered the most preventable risk factor for coronary artery disease.3,21,26 Regular physical exercise decreases the risk for many health problems including non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus, osteoporosis, osteoarthritis, cardiovascular disease, cancer, hypertension, obesity and hypercholestrolemia.3,27–34 Regular exer-cise was also found to be associated with better general well-being35 and life expectancy36,37 in addition to lesser mortality rates .4,22

Specific prescription of physical exercise should be given to almost all patients, bearing in mind the age and general condition of each individual .3,23 Almost every patient including elderly people and those with severe coronary artery disease and patients with congestive heart failure, has the potential of benefiting from regular physical exercise.3,24,25,37

The physiologic effects of exercise depend on its type, intensity, duration and frequency.38 Recreational physical exercise can be classified into the following two types:38,39

1. Isometric (static or anaerobic) exercise:

This type is characterized by an increase in muscle tension without much change in fiber length, with substantial energy expenditure. Examples are weight lifting, hand grip exercises and pushing or pulling against a resistance. Anaerobic exercise increases total peripheral resistance and thus leads to considerable rise in blood pressure. Therefore, this type of exercise is not suitable for patients with cardiovascular disease. It is, however, suitable for athletes to build up bulk muscle.

2. Isotonic (dynamic or aerobic) exercise:

Aerobic exercise is characterized by shortening of muscle fibers with little increase in tension. Examples are swimming, bicycling and running. In aerobic exercise, total peripheral resistance decreases but heart rate and cardiac output increase. This is the type of exercise which is recommended to the general population on a regular basis. The more frequent and prolonged the aerobic exercise, the better its effects, provided that the patient's condition permits it.33,40

NON-CONTROL OF BODY WEIGHT

The annual economic losses due to obesity are calculated in billions of dollars.41 The prevalence of obesity in UK (1986) approached 12% in males and 8% in females.42 The situation in USA is even worse, where about one quarter of all adult Americans are overweight.42,43 Further- more, recent data indicated a linear increase in the average weight of American adults over the last few decades.41

Obesity is defined by WHO as a body mass index (BMI) more than 30 kg per square metre.42,44 The risk of overweight related problems, however, starts at body mass index of 25 kg per square metre.41 Overweight adversely affects the general health of people.35 It is considered to be a risk factor for non insulin dependent diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, gallstones, low back pain, certain cancers (colorectal and prostate in males, and cervical, breast and ovarian in females) and premature death.4,26,43–48

Distribution of regional, rather than total, body fat is increasingly gaining special importance. Recent research has demonstrated an association between the amount of visceral fat and the disturbances in glucose tolerance and lipid concentrations.46 Visceral fat, which can be measured by computerized tomography,46 was found to correlate highly significantly with waist-to-hip ratio.49 Cut off points for waist-to-hip ratio, above which high risk begins, were generally agreed to be 0.95 for men and 0.80 for women.50 High waist-to-hip ratio (upper body obesity) is associated with high risk for hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hypercholestrolemia, hypertriglyceridemia, low HDL, hyperinsulinemia and mortality from cardiovascular disease.44,46,50–54

Causes of obesity include a variety of medical, genetic and lifestyle factors. The easiest and most effective modality of prevention is to deal with the lifestyle factors, namely diet and physical activity.42,55 Prevention of obesity has been proved to be highly beneficial in preventing obesity-related health hazards, resulting in a better life expectancy and general health.11,20–23,32,56–58

NON-USE OF SEAT BELTS

Seat belts were introduced for the first time in the mid 1950s. By the late 1960s, seat belts were required in all new cars in USA. The introduction of interlock devices that prevent ignition if the driver's safety belt was not fastened, resulted in a significant improvement in the use of seat belts. Unfortunately, these devices were met with strong opposition by the public. Minimal improvement occurred with the introduction of warning lights and buzzers. In the USA (1984), legislation for the use of seat belts took place and resulted in increased compliance from 15% to about 50% in a short time.59

Studies from all over the world documented the benefits of seat belts and the hazards of non-use.11,27,35,60–65 There was more than 60% reduction in the severity of injuries, hospital admissions and hospital charges for users of seat belts.66 In Germany, morbidity and mortality due to road traffic accidents have shown substantial decrease when the rates of seat belts use increased.67 Interestingly it was found that parents’ use of seat belts, influenced children to do the same68 and that non-use of seat belts was associated with other unhealthy behavior such as smoking, overweight and lack of exercise.62,69

The airbag was recently introduced in many new motor vehicles as a supplement to seat belts. This new device has proved quite effective but its effect is still limited due to the relatively small number of cars equipped with them.70

THE SITUATION IN SAUDI ARABIA

There is a belief that during the last few decades some unhealthy lifestyles have been adopted by Saudis. However, published national studies that quantify these important assumptions are few.71 Most of the studies referred to below are apparently limited by being either retrospective, based on insufficient recording systems, clinic-based, hospital-based, or done on a small scale. These limitations do not rule out the importance of such studies in providing us with rough estimates of the extent of the problem in our country.

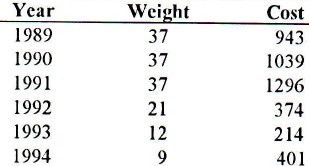

Available data point to cigarette smoking as an important health problem in Saudi Arabia.72 Following the steady increase in the quantity of tobacco imported before 1987, national statistical data73,74 showed significant reduction in tobacco imports during the period from 1989 to 1994 (Table 1). Tobacco, however, is still considered a burden on the health and economy of Saudi population. It was found that 33% of male medical students in Riyadh smoke cigarettes.75 The prevalence among other University students was even higher (37%).76 In secondary schools, 22% of male students admitted being regular smokers.77 While smoking is considered socially unacceptable among females, up to 12% of university female students reported being current smokers.78

Table 1.

The weight (in thousand tons) and cost (in million SR) of tobacco imported during the period 1989-1994

In 1987, A1-Turki found that the smoking rate in the Eastern Province was 37% and 9% for adult males and females.79 In Al-Baha Province, in 1989, Al-Bedah reported a higher rate among males; about 53% of adult males being smokers. The overall rate, however, was 29% because cigarette smoking was absolutely unacceptable among females in such a rural community.80

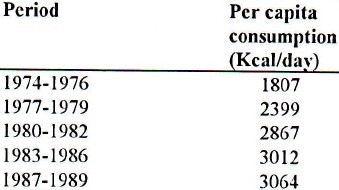

Over the past two decades, the per capita calory consumption of Saudis has shown a steady increase (Table 2).81,82 Considering BMI of 25 as a cut-off point, Binhemd et a183 found 52% of males and 65% of females visiting the primary care clinic of King Fahd Hospital of the University at Al-Khobar, to be obese. Despite the limitation of such a study, the high figures it showed were supported by findings of Al-Shammari et al.47 Al-Abbad (1995) demonstrated a prevalence of obesity (defined as a BMI of ≥ 85th percentile) approaching 29% among female students aged 11-21 years.84

Table 2.

The per capita daily dietary consumption (Kcal/day) of Saudis over the period 1974-1989

Data about recreational aerobic physical activity of Saudis are not yet available. However, if we consider the body weight as an indirect indicator, the physical activity of Saudi population does not seem to be improving in relation to other healthy life styles.

The number of cars imported by Gulf countries increased by 1031% between 1971 and 1984, and deaths due to road traffic accidents increased by 307% in the same period. In Saudi Arabia, the number of cars increased by 2400% within the 10 years ending 1986 and this was associated with 469% increase in trauma cases and a 561% increase in related deaths.85

It is not surprising, therefore, that road traffic accidents constitute the leading cause of death in the age group 16-36 years. In 1984, mortality due to road traffic accidents approached 15 deaths per day. This number reflects only those who died at the scene of the accident. Those who died en route to the hospital or following admission were almost double.86 In 1980, Khawashki estimated the economic loss in Saudi Arabia due to road traffic accidents as Saudi Rivals 4,776,836 per day.87 In Asir region alone, which contains 2.5% of all cars in the country, about 7760 persons were involved in road traffic accidents in the period from 1989-1991; 62% of these were injured, and 12% died.88

Fast driving, driving by children under 18 years of age and driving without a license were found to contribute enormously towards road traffic accidents.88–90 The authorities have responded to this by taking different measures including the imposition of severe penalties to offenders. Surprisingly, the mandatory use of seat belts which is probably easier to enforce, is still receiving little attention. In a study done by Marwa et a1,91 none of the victims of road traffic accidents were found to have had the seat belts fastened. A few small studies attempted to measure the rate of seat belts use in certain localities in the country and ended up with the rates ranging from 7--19%.90,92,93 Unfortunately, to the best of the author's knowledge, there have been no nation-wide studies on the rate of seat-belt use.

There is an obvious paucity of research about the lifestyle of Saudi population. However, the data in hand do not call for optimism. Indeed, there is a great need to enforce healthy behavior in the Saudi community as means of promoting healthy lifestyle towards the eventual goal of positive health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Leaderer BP, Samet JM. Passive smoking and adults: new evidence for adverse effects. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;150:1216–8. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.150.5.7952542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meltzer EO. Prevalence, economic, and medical impact of tobacco smoking. Ann Allergy. 1994;73:381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kerr CP. Eight underused prescriptions. Am Fam Physician. 1994;50:1497–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Breslow L, Enstrom JE. Persistence of health habits and their relationship to mortality. Prev Med. 1980;9:469–83. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(80)90042-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parkin DM, Pisani P, Lopez AD, Masuyer E. At least one in seven cases of cancer is caused by smoking.Global estimates for 1985. Int J Cancer. 1994;59:494–504. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910590411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peto R, Lopez AD, Boreham J, Thun M, Heath C. Mortality from tobacco in developed countries: indirect estimation from national vital statistics. Lancet. 1992;339:1268–78. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)91600-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doll R, Peto R, Eheatley K, Gray R, Sutherland I. Mortality in relation to smoking: 40 years′ observations on male British doctors. BMJ. 1994;309:901–11. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6959.901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wynder EL, Hoffman D. Smoking and lung cancer: scientific challenges and opportunities. Cancer Res. 1994;54:5284–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heineman EF, Zahm SH, McLaughlin JK, Vaught JB. Increased risk of colorectal cancer among smokers: results of a 26-year follow-up of US veterans and a review. Int J Cancer. 1995;59:728–38. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910590603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gidding SS, Morgan W, Perry C, Isabel-Jones J, Bricker JT. Active and passive tobacco exposure: a serious pediatric health problem. Circulation. 1994;90:2581–90. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robbins JA. Preaching in your practice - What to tell patients to help them live longer. Prim Care. 1980;7:549–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Nozha M. Tobacco and the third world. Annals of Saudi Medicine. 1991;11:133–4. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.1991.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Epstein FH. The relationship of lifestyle to international trends in CHD. Int J Epidemiol. 1989;18:203S–209S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Council on Scientific Affairs, American Medical Association. Environmental tobaccoo smoke - Health effects and prevention policies. Arch Fam Med. 1994;3:865–71. doi: 10.1001/archfami.3.10.865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steenland K. Passive smoking and the risk of heart disease. JAMA. 1992;267:94–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luenberger P, Schwartz J, Ackerman-Liebrich U, Blaser K, Bolognini G, Bongard JP, et al. Passive smoking exposure in adults and chronic respiratory symptoms (SAPALDIA study) Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;150:1221–8. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.150.5.7952544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bener A, Al-Frayh A, Ozkaragoz F, Al-Jawadi TQ. Passive smoking effects on wheezy bronchitis. Annals of Saudi Medicine. 1993;13:222–5. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.1993.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mainous AG, Hueston WJ. Passive smoke and low birth weight: evidence of a threshold effect. Arch Fam Med. 1994;3:875–8. doi: 10.1001/archfami.3.10.875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clausen JL. Questions < answers. AJR. 1994;163:1523–4. doi: 10.2214/ajr.163.6.7992759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsevat J, Weinstein MC, Williams LW, Tosteson AN, Goldman L. Expected gains in life expectancy from various coronary heart disease risk factor modifications. Circulation. 1991;83:1194–201. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.83.4.1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manson JE, Tosteson H, Ridker PM, Satterfield S, Hebert P, O’Connor GT, et al. The primary prevention of myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1406–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199205213262107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paffenbarger RS, Hyde RT, Wing AL, Lee I, Jung DL, Kampert JB. The association of changes in physical-activity level and other lifestyle characteristics with mortality among men. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:538–45. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199302253280804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simon HB. Patient-directed, nonpres-cription approaches to cardiovascular disease. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:2283–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wheatley D, Bass C. Can lifestyle changes reverse coronary heart disease. The lifestyle heart trial? Br J Psychiatry. 1991;158:264–7. doi: 10.1192/bjp.158.2.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koplan JP, Livengood JR. The influence of Changing Demographic Patterns on our Health Promotion Priorities. Am J Prev Med. 1994;10(3S):42S–44S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kupari M, Koskinen P, Virolainen J. Correlates of left ventricular mass in a population sample aged 36-37 years, focus on lifestyle and salt intake. Circulation. 1994;89:1041–50. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.3.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Knudson M, Hosokawa M. Evaluation of an educational intervention to increase health promotion by residents. Journal of Medical Education. 1988;63:309–15. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198804000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blair N, Kohl HW, Pafferbarger RS, Clark DG, Cooper H, Gibbons LW. Physical fitness and all-cause mortality-prospective study of healthy men and women. JAMA. 1989;262:2395–401. doi: 10.1001/jama.262.17.2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bassey J, Fentem P, Turnbull N. Reasons for advising exercise. Practitioner. 1987;231:1605–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.James WC. Preventive medicine as a component of the office visit - Is it time for change? West J Med. 1994;161:181–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Staessen JA, Fagard R, Amery A. Life style as a determinant of blood pressure in the general population. Am J Hypertens. 1994;7:685–94. doi: 10.1093/ajh/7.8.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ravussin E, Valencia ME, Esparza J, Beennet PH, Schulz LO. Effects of a traditional lifestyle on obesity in Pima Indians. Diabetes Care. 1994;17:1067–74. doi: 10.2337/diacare.17.9.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anroll B, Beaglehole R. Does physical activity lower blood pressure: a critical review of the clinical trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:439–47. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90093-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Amer N, Abdel-Aziz M. Effects of exercise on healthy non-athlete Jordanian individuals. Saudi Medical Journal. 1991;12:212–4. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wiley JA, Camacho TC. Life-style and future health: evidence from the Alameda county study. Prev Med. 1980;9:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(80)90056-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wicklin B. Sports and recreation for a healthy life. World Health Forum. 1992;13:250–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sherman SE, D’Agostino RB, Cobb JL, Kannel WB. Does exercise reduce mortality rates in the elderly.Experience from the Framingham Heart Study? Am Heart J. 1994;128:965–72. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(94)90596-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rubenstein E, Federman D, editors. Sports Medicine. Scientific American Inc; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Simon HB. Exercise and prevention of cardiovascular disease. In: Goroll AH, May LA, Mulley AG, editors. Primary care Medicine: office evaluation and management of the adult patient. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1995. pp. 81–8. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wilson PW, Paffenbarger RS, Morris JN, Havlik RJ. Assessment methods for physical activity and physical fitness in population studies: Report of a NHLBI workshop. Am Heart J. 1986;111:1177–92. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(86)90022-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hintlian CJ. Evaluation of excessive weight gain and obesity. In: Goroll AH, May LA, Mulley AG, editors. Primary care medicine: office evaluation and management of the adult patient. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1995. pp. 42–8. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dyer RG. Traditional treatment of obesity. Bailliere's Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994;8:661–88. doi: 10.1016/s0950-351x(05)80290-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Itallie TB. Health implications of overweight and obesity in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 1985;103:983–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-103-6-983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hodge AM, Zimmet PZ. The epidemiology of obesity. Bailliere's Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994;8:577–99. doi: 10.1016/s0950-351x(05)80287-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Manson KE, Stampfer MJ, Hennekens CH, Willet WC. Body weight and longevity - a reassessment. JAMA. 1987;257:353–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zamboni M, Armellini F, Cominacini L, Turcato E, Todesco T, Bissoli L, et al. Obesity and regional body fat distribution in men: separate and joint relationships to glucose tolerance and plasma lipoproteins. Am J Clin Nutr. 1994;60:682–7. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/60.5.682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Al-Shammari SA, Khoja TA, Kremli M, Al-Balla SR. Low back pain and obesity in primary health care, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Medical Journal. 1994;15:223–6. [Google Scholar]

- 48.McCarron DA, Reusser ME. Body weight and blood pressure regulation. Am J Clin Nutr. 1996;63:423S–425S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/63.3.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ashwell M, Cole TJ, Dixon AK. Obesity: new insight into the anthropometric classification of fat distribution shown by computed tomography. BMJ. 1985;290:1692–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.290.6483.1692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Croft JB, Keenan NL, Sheridan DP, Wheeler FC, Speers MA. Waist-to-hip ratio in biracial population: measurement, implications, and cautions for using guidelines to define high risk for cardiovascular disease. J Am Diet Assoc. 1995;95:60–4. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(95)00014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kaplan NM. Upper-body obesity, glucose intolerance, hypertriglyceridemia, and hypertension. Arch Intern Med. 1989;149:1514–20. doi: 10.1001/archinte.149.7.1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kissebah AH, Vydelingum N, Murray R, Evans DJ, Hartz AJ, Kalkhoff RK, Adams PW. Relation of body fat distribution to metabolic complications of obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1982;5-1:254–60. doi: 10.1210/jcem-54-2-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Blair D, Habicht J, Sims EA, Syhvester D, Abraham S. Evidence for an increased risk for hypertension with centrally located body fat and the effect of race and sex on this risk. Am J Epidemiol. 1984;119:526–40. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Haffner SM, Stern MP, Hazuda HP, Pugh J, Patterson JK. Do upper-body and centralized adiposity measure different aspects of regional body-fat distribution. - Relationship to non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, lipids, and lipoproteins? Diabetes. 1987;36:43–51. doi: 10.2337/diab.36.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Canadian Fitness and Lifestyle Research Institute. Physical activity and obesity. Can Med Assoc J. 1994;151:1732. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hubert HB, Feinleib M, McNamara PM, Castelli WP. Obesity as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease: a 26-year follow-up of participants in the Framingham heart study. Circulation. 1983;67:968–76. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.67.5.968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schotte DE, Stunkard AJ. The effects of weight reduction on blood pressure in 301 obese patients. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150:1701–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Savage DD, Levy D, Dannenberg AL, Garrison RJ, Castelli WP. Association of echocardiographic left ventricular mass with body size, blood pressure and physical activity (The Framingham Study) Am J Cardiol. 1990;65:371–6. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(90)90304-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nichols JL. Changing Public Behavior for Better Health: Is Education Enough? Am J Prey Mcd. 1994;10(3 Suppl):19S–22S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Steed D. The case for safety belt use. JAMA. 1988;260:3651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Newman RJ. A prospective evaluation of the protective effect of car seat belts. J Trauma. 1986;26:561–4. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198606000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sleet DA. Motor vehicle trauma and safety belt use in the context of public health priorities. J Trauma. 1987;27:695–702. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198707000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Polen MR, Friedman GD. Automobile injury - selected risk factors and prevention in the health care setting. JAMA. 1988;259:77–80. doi: 10.1001/jama.259.1.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dreghorn CR. The effect of seat belt legislation on a district general hospital. Injury. 1985;16:415–8. doi: 10.1016/0020-1383(85)90061-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Robertson LS. Reducing death on the road: the effects of minimum safety standards, publicized crash tests, seat belts, and alcohol. Am J Public Health. 1996;86:31–4. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.1.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Orsay EM, Turbull TL, Dunne M, Barrett JA, Langenberg P, Orsay CP. Prospective study of the effect of safety belts on morbidity and health care costs in motor-vehicle accidents. JAMA. 1988;260:3598–603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Marburger EA, Friedel B. Seat belt legislation and seat belt effectiveness in the Federal Republic of Germany. J Trauma. 1987;27:703–5. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198707000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Macknin ML, Gustafson C, Gassman J, Barich D. Office education by pediatri-cians to increase seat belt use. AJDC. 1987;141:1305–7. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1987.04460120067037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dillow I, Swann C, Cliff KS. A study of the effect of a health education program in promoting seat-belt wearing. Health Education Journal. 1981;40:14–8. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Barton ED. Airbag safety: deployment in an automobile crash with a fall from height. J Emerg Med. 1995;13:481–4. doi: 10.1016/0736-4679(95)80004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Al-Nozha M. Prevention of coronary artery disease - time for action! Annals of Saudi Medicine. 1995;15:309–10. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.1995.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Al-Tamimi TM, Al-Bar AA, Al-Suhaimi S, Ibrahim E, Ibrahim A, Wosornu L, Gabriel GS. Lung cancer in the eastern region of Saudi Arabia: a population-based study. Annals of Saudi Medicine. 1996;16:3–11. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.1996.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Foreign trade statistics. Riyadh: Ministry of Finance and National Economy; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Riyadh: Ministry of Finance and National Economy; 1994. Import statistics. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jarallah JS. Smoking habits of medical students at King Saud University, Riyadh. Saudi Medical Journal. 1992;13:510–3. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Taha A, Bener A, Noah MS, Saeed A, Al-Harthy S. Smoking habits of King Saud University students in Riyadh. Annals of Saudi Medicine. 1991;11:141–3. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.1991.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Felimban FM, Jarallah JS. Smoking habits of secondary school boys in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Medical Journal. 1994;15:438–42. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Felimban FM. The smoking practices and attitudes towards smoking of female university students in Riyadh. Saudi Medical Journal. 1993;14:220–4. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Al-Turki KA. Cigarette smoking in adults in Dammam and three Hijras in the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia [dissertation] Dammam (Saudi Arabia): King Faisal University; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Al-Bedah AM. Smoking pattern in Al-Baha region of Saudi Arabia and Anti-smoking program [dissertation] Dammam (Saudi Arabia): King Faisal University; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Vol. 2. Riyadh: Ministry of Agriculture and Water, Department of Economic Studies and Statistics; 1986. Saudi Arabian food balance sheets. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Vol. 3. Riyadh: Ministry of Agriculture and Water, Department of Economic Studies and Statistics; 1989. Saudi Arabian food balance sheets. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Binhemd T, Larbi EB, Absood G. Obesity in a primary health care center: a retrospective study. Annals of Saudi Medicine. 1991;11:163–6. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.1991.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Al-Abbad FA. Prevalence of obesity & risk factors among single female inter-mediate & high school students in Al-Khobar - Eastern Province, Saudi Arabia [dissertation] Dammam (Saudi Arabia): King Faisal University; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Al-Tukhi MH. Road traffic accidents: statistics and data comparing the Gulf countries and the Riyadh area. Saudi Medical Journal. 1990;11:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Al-Rodhan N, Lifeso RM. Traffic accidents in Saudi Arabia: an epidemic. Annals of Saudi Medicine. 1986;6:69–70. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.1986.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Khawashki E. Socioeconomic impact of road traffic accidents in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Medical Journal. 1980;1:246–8. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Badawi IA, Alakija W, Aziz MA. Road traffic accidents in Asir region, Saudi Arabia: pattern and prevention. Saudi Medical Journal. 1995;16:257–260. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Tamimi TM, Daly M, Bhatty MA, Lutfi AM. Causes and types of road injuries in Asir province, Saudi Arabia, 1975-1977: Preliminary study. Saudi Medical Journal. 1980;1:249–56. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Al-Ghamdi KS. Attitudes and practices of the drivers towards driving in the Jubail Naval Base. Journal of Family and Community Medicine. 1995;2(2):41–48. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Marwah S, Al-Habdan IM, Sankaran-Kutty M, Parashar S. Road traffic accidents admissions in a university hospital in Saudi Arabia (a pilot study) Saudi Medical Journal. 1990;11:389–91. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Mufti MH. Medico-legal aspects of seat belt legislation in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Medical Journal. 1986;7:84–90. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Shawan S, Al-Arfaj A, Hegazi M, Al-Habdan I, Wosornu L. Voluntary usage of seat belts in the eastern province of Saudi Arabia. Saudi Medical Journal. 1992;13:25–8. [Google Scholar]