Abstract

A significant need exists for orthopedic implants that can intrinsically resist bacterial colonization. In this study, three biomaterials that are used in spinal implants – titanium (Ti), polyether-ether-ketone (PEEK), and silicon nitride (Si3N4) – were tested to understand their respective susceptibility to bacterial infection with Staphylococcus epidermidis, Staphlococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli and Enterococcus. Specifically, the surface chemistry, wettability, and nanostructured topography of respective biomaterials, and the effects on bacterial biofilm formation, colonization, and growth were investigated. Ti and PEEK were received with as-machined surfaces; both materials are hydrophobic, with net negative surface charges. Two surface finishes of Si3N4 were examined: as-fired and polished. In contrast to Ti and PEEK, the surface of Si3N4 is hydrophilic, with a net positive charge. A decreased biofilm formation was found, as well as fewer live bacteria on both the as-fired and polished Si3N4. These differences may reflect differential surface chemistry and surface nanostructure properties between the biomaterials tested. Because protein adsorption on material surfaces affects bacterial adhesion, the adsorption of fibronectin, vitronectin, and laminin on Ti, PEEK, and Si3N4 were also examined. Significantly greater amounts of these proteins adhered to Si3N4 than to Ti or PEEK. The findings of this study suggest that surface properties of biomaterials lead to differential adsorption of physiologic proteins, and that this phenomenon could explain the observed in-vitro differences in bacterial affinity for the respective biomaterials. Intrinsic biomaterial properties as they relate to resistance to bacterial colonization may reflect a novel strategy toward designing future orthopedic implants.

Keywords: silicon nitride, nanostructure, anti-infective, biofilm, protein adsorption

Introduction

In the year 2008, an estimated 413,171 spinal fusion operations, 436,736 primary total hip arthroplasty (THA), and 680,839 primary total knee arthroplasty (TKA) procedures were performed in the United States alone,1 leading to an approximately US$13 billion market for orthopedic implants.2 Future demand for such implants is expected to rise. When otherwise well functioning orthopedic implants become colonized with bacteria, significant patient morbidity can follow. The reason is that bacteria adhere to implant surfaces and are resistant to host immune mechanisms and systemic antibiotics. Treatment of such implant-related infections requires extensive repeat surgery, implant extrication, extended duration of systemic antibiotic therapy, bone loss, and substantial cost, suffering, and disability.

Implant-related infections occur in spine surgery between 2.6% and 3.8% of the time.3 In hip replacement surgery, deep infection occurs at 1.63% at 2-years post-operatively,4 and the figures for knee replacement are about 1.55%.5 These numbers underestimate the true incidence of infection because of difficulties related to clinical diagnoses, and a paucity of credible data from epidemiological surveys. Mortality rates from complications related to deep prosthetic infections in THA and TKA are reportedly between 2.7% and 18%,6 and infection is the most common reason for repeat surgery after otherwise successful prosthetic joint replacement.7 The incidence of infection in THA and TKA may be increasing, probably due to improved detection and also because of evolving antibiotic-resistant bacteria strains. Treatment costs related to infected orthopedic implants can range from 1.52 to 1.76 times the cost of the original surgery.8 While orthopedic implants are deemed expensive, their costs are easily overwhelmed by the overall treatment cost of implant-related infections.9 Therefore, there is considerable interest in reducing the risk of infections related to orthopedic implants.

In addition to total joint replacement and spinal devices, orthopedic implants are also manufactured as screws, plates, and percutaneously implanted pins to treat fractures; bacterial contamination of such can lead to poor bone healing.10 Unless acute implant infections can be overcome expeditiously, adjacent tissues become colonized with bacteria,11–13 and the risk of chronic bone infection (osteomyelitis) increases.13,14 Osteomyelitis can complicate fracture treatment with metal external fixator devices up to 4% of the time.11–13 Ultimately, orthopedic infections lead to implant loosening, nonhealing of fractures, and device failures.12

Bacteria present in the bloodstream and body tissues can usually be cleared by host immune mechanisms and antibiotic treatment.15 However, once bacteria colonize implant surfaces by expressing a biofilm layer, they become relatively impervious to such nonsurgical measures. Biofilm production is accompanied by changes in gene expression and growth rates such that host immune mechanisms are rendered ineffective, leading to a chronically infected environment around the implant.15–18 A related clinical concern pertains to the development of antibiotic-resistant strains of bacteria, including S. aureus and S. epidermidis, which have been well documented in the clinical orthopedic setting.19,20 Any material science-derived strategy that discourages bacterial colonization of implant surfaces will therefore be of value in reducing the need for systemic antibiotic therapy and surgical removal of infected implants.20

Changing implant surface texture from a micron-sized to a nanometer-sized topography affects osteoblast adhesion21–26 and subsequent cellular function, while decreasing competitive fibroblast activity.27,28 Nanoroughened titanium (Ti) made by electron-beam evaporation29 and nanotubular and nanotextured Ti created by anodization can enhance osteoblast adhesion and function (such as alkaline phosphatase synthesis, calcium deposition, and collagen secretion) when compared with micron nanosmooth control surfaces.30 Increased protein adsorption on nanotextured Ti surfaces is correlated with improved osteoblast function.31–33 The authors have previously shown that by selectively engineering the surface topography of a biomaterial, bacteria adhesion can be decreased.34,35

Because silicon nitride (Si3N4) is used in spinal reconstructive surgery today, the adhesion of multiple bacteria species onto polished and nanostructured versions of this biomaterial was examined, using two other orthopedic biomaterials (Ti and poly-ether-ether-ketone [PEEK]) as controls. The null hypothesis was that bacterial adhesion and surface protein adsorption (fibronectin, vitronectin, and laminin) would not differ between these materials. Gram-positive S. epidermidis and S. aureus, and Gram-negative P. aeruginosa, E. coli, and Enterococcus were tested because these strains are commonly implicated in orthopedic implant infections.19

Materials and methods

Biomaterials

Si3N4 was supplied by Amedica Corporation (Salt Lake City, UT) in two surface morphologies; with an “as-fired” surface that has nanostructured features, and a smooth polished surface, respectively. Biomedical grade 4 titanium (Fisher Scientific, Continental Steel and Tube Co, Fort Lauderdale, FL) and PEEK Optima® (Invibio, Lancashire, United Kingdom) were obtained with typical machined surfaces. The surfaces of these materials were characterized for morphology and roughness using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (using an LEO 1530 VP FE-4800 field-emission scanning electron microscope [Zeiss, Peabody, MA]). Specimens of 1 cm × 1 cm dimensions first underwent sessile water-drop tests to assess material wetting characteristics using a KRÜSS easy drop contact angle instrument connected to the drop shape analysis program (version 1.8) (KRÜSS GmbH, Hamburg, Germany) in accordance with an ASTM standard (D7334-08).36 Prior to bacterial exposure, all samples underwent sterilization with ultra violet light exposure for 24 hours on all sides, and roughness characterization with standard SEM.

Bacteria studies

Bacteria were inoculated (105) onto the material surfaces for 4, 24, 48, and 72 hours. S. epidermidis, P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, E. coli, and Enterococcus were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) (strains 35984, 25668, 25923, 26, and 6569, respectively). The dry pellet was rehydrated in 6 mL of Luria broth (LB) consisting of 10 g tryptone, 5 g yeast extract, and 5 g NaCl per liter double-distilled water with the pH adjusted to 7.4 (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) (HyClone; Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) at 10% concentration was added to the LB, and the bacteria solution was agitated under standard cell conditions (5% CO2/95% humidified air at 37°C) for 24 hours until the stationary phase was reached. The second passage of bacteria was diluted at a ratio of 1:200 into fresh LB supplemented with 10% FBS and incubated until it reached the stationary phase. The second passage was then frozen in one part LB and 10% FBS and one part glycerol (Sigma-Aldrich) and stored at −18°C. All experiments were conducted from this frozen stock. One day before bacterial seeding for experiments, a sterile 10 μL loop was used to withdraw bacteria from the frozen stock and to inoculate a centrifuge tube with 3 mL of fresh LB supplemented with 10% FBS.

Bacterial function was determined by crystal violet staining and a live/dead assay (Molecular Probes®, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) using previously described methods.35 For the live/dead assay, at the end of the prescribed time period, substrates were rinsed twice with Tris-buffered saline (TBS) comprised of 42 mM Tris-HCl, 8 mM Tris base, and 0.15 M NaCl (Sigma-Aldrich) and then incubated for 15 minutes with the BacLight™ Live/Dead solution (Life Technologies) dissolved in TBS at the concentration recommended by the manufacturer. Substrates were then rinsed twice with TBS and placed into a 50% glycerol solution in TBS prior to imaging. Bacteria were visualized and counted in situ using a Leica DM5500 B fluorescence microscope with image analysis software captured using a Retiga™ 4000R camera (QImaging, Surrey, BC, Canada).

Protein adsorption

Standard fibronectin, vitronectin, and laminin enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) were performed after soaking material samples in bacterial media (LB supplemented with 10% FBS) used above for 20 minutes, 1 hour, and 4 hours, as previously described.35 Substrates were placed in a standard 24-well culture plate and immersed in 1 mL of LB supplemented with and without 10% FBS for 20 minutes, 1 hour, and 4 hours at 37°C in 5% CO2/95% humidified air. After rinsing in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), areas that did not absorb proteins were blocked and incubated for 1 hour in bovine serum albumin, BSA (2 wt% in PBS, Sigma-Aldrich). Substrates were again rinsed twice with PBS before either fibronectin, vitronectin, or laminin were directly linked respectively with primary rabbit antibovine fibronectin, anti-vitronectin, or anti-laminin (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA) at a concentration of 6 μg/mL in 1% BSA for 1 hour at 37°C in 5% CO2/95% humidified air. After rinsing three times with 0.05% Tween 20® (AkzoNobel, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) for 5 minutes with each rinse, the samples were further incubated for 1 hour with a secondary goat anti-rabbit conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) at a concentration of 10 μg/mL in 1% BSA. Following triple rinsing with 0.05% Tween 20 for 5 minutes per rinse, surface-adsorbed protein was measured with an ABTS substrate kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) that reacted only with the HRP. Light adsorbance was measured at 405 nm on a spectrophotometer and analyzed with computer software. The average adsorbance was subtracted by the average adsorbance obtained from the negative controls soaked in LB with no FBS. ELISA was performed in duplicate and repeated three times per substrate.

Statistical analysis

Each experiment was done in triplicate with new bacteria, media, and samples. Time series data for biofilm formation, bacteria colonization, and growth were curve-fit to either linear or exponential functions. Hypothesis testing was completed using regression analysis and confidence intervals in accordance with techniques previously described.37 Paired comparison t-tests were used to assess significance for the protein adsorption studies; a P-value of <0.05 was deemed statistically significant.

Results

Comparison of materials

Relevant properties of the three biomaterials tested are compared in Table 1. Si3N4 has a protective surface layer that is composed of charged SiNH3+, SiOH2+, SiO−, and neutral SiNH2 and SiOH groups.38 The presence of the amine groups leads to a high isoelectric point (between 8 and 9) and an overall net positive surface charge.38,39 Ti has a native oxide layer (TiO2) which has an isoelectric point of about 4.5 and therefore a negative surface charge at pH 7.40 PEEK surfaces have polymeric chains ending in –OH groups, that yield an isoelectric point of about 4.5 and a negative surface charge.41 Si3N4 has the lowest wetting angle and greater hydrophilicity when compared with PEEK or Ti (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparative properties of medical grades of Si3N4, ASTM35 grade 4 Ti, and PEEK

| Property | Units | Si3N4 | Ti-ASTM grade 4 | PEEK optima® |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Composition | NA | Si3N4, Y2O3, AI2O3 | Chemically pure | Chemically pure |

| Surface composition | NA | SiNH2 and SiOH | TiO2 layer | –OH groups |

| Surface roughness (AFM) | nm | 10.1*, 25.3** | 3.06 | 1 |

| Isoelectric point | NA | 9 | ~4.5 | ~4.5 |

| Surface charge at pH = 7 | NA | Positive | Negative | Negative |

| Sessile water drop wetting angle | Degrees | 39 | 76 | 95 |

Notes:

Polished surface;

as-fired surface.

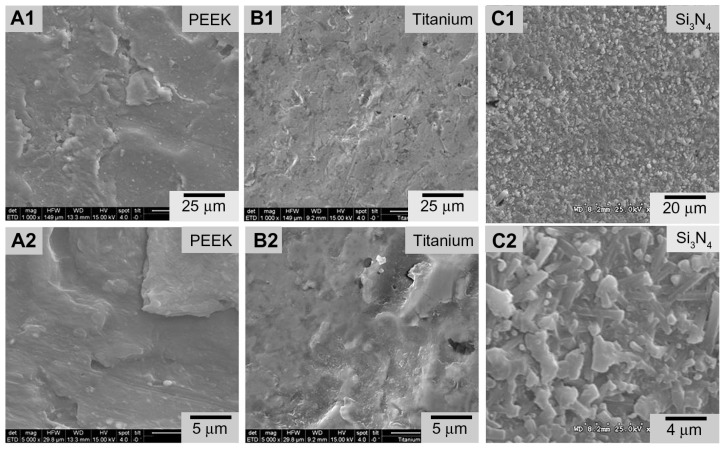

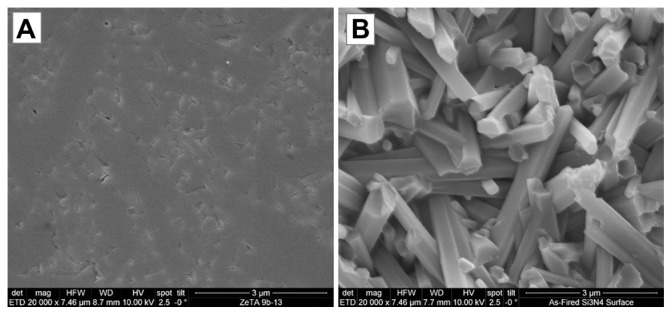

SEM images of biomaterial surfaces are illustrated in Figures 1 and 2. Of the materials tested, PEEK and Ti had machined surfaces, while Si3N4 was in as-fired and polished formulations. SEM images of PEEK and Ti show a micron-rough surface typical of machined materials. The as-fired Si3N4 had nanostructured surface features with a larger total surface area, as shown in the high magnification images (Figure 2). The as-fired Si3N4 surface morphology reflects the natural condition of this material subsequent to densification by sintering and hot-isostatic pressing.42 The surface is composed of randomly oriented acicular protruding grains typically less than 1 μm in cross-section, yielding a unique nanotexture (Figure 2B). Note that individual hexagonal grains of Si3N4 have definitive linear facets (in cross-section) and sharp corners at the termination of the acicular grains, which are typically less than 100 nm. These unique features may play a role in interaction with bacteria, resulting in their lysis. This is contrasted to the highly polished Si3N4 surface of Figure 2A in which the acicular asperities were removed.

Figure 1.

Scanning electron microscopy surface microstructures of PEEK Optima®, Ti, and Si3N4: (A1) PEEK 1000×; (A2) PEEK 5000×; (B1) Ti 1000×; (B2) Ti 5000×; (C1) Si3N4 1000×; (C2) Si3N4 5000×.

Abbreviation: PEEK, poly-ether-ether-ketone.

Figure 2.

Scanning electron microscopy surface microstructure of polished and as-fired Si3N4: (A) polished surface 20,000×; (B) as-fired surface 20,000×.

Surface roughness measurements derived from atomic force microscopy (AFM) measurements are summarized in Table 1. Results were 25 nm, 10 nm, 3 nm, and 1 nm for the asfired Si3N4, polished Si3N4, Ti, and PEEK, respectively. These AFM surface roughness values differ from those that could be obtained using contact profilometry because the areal sampling size of AFM is small compared with contact profilometry. It is obvious from a comparison of the features in Figure 1 that the micron scale roughness of Si3N4 is similar to that of Ti and PEEK, although there are notable topographical differences. However, the AFM measurements were made over fractions of nanometers. In effect, AFM is measuring the nanoroughness of the materials inbetween micron-sized surface features. These results show that as-fired Si3N4, polished Si3N4, Ti, and PEEK have markedly different surface chemistries and topographies that could affect bacterial and protein adhesion.

Bacteria studies

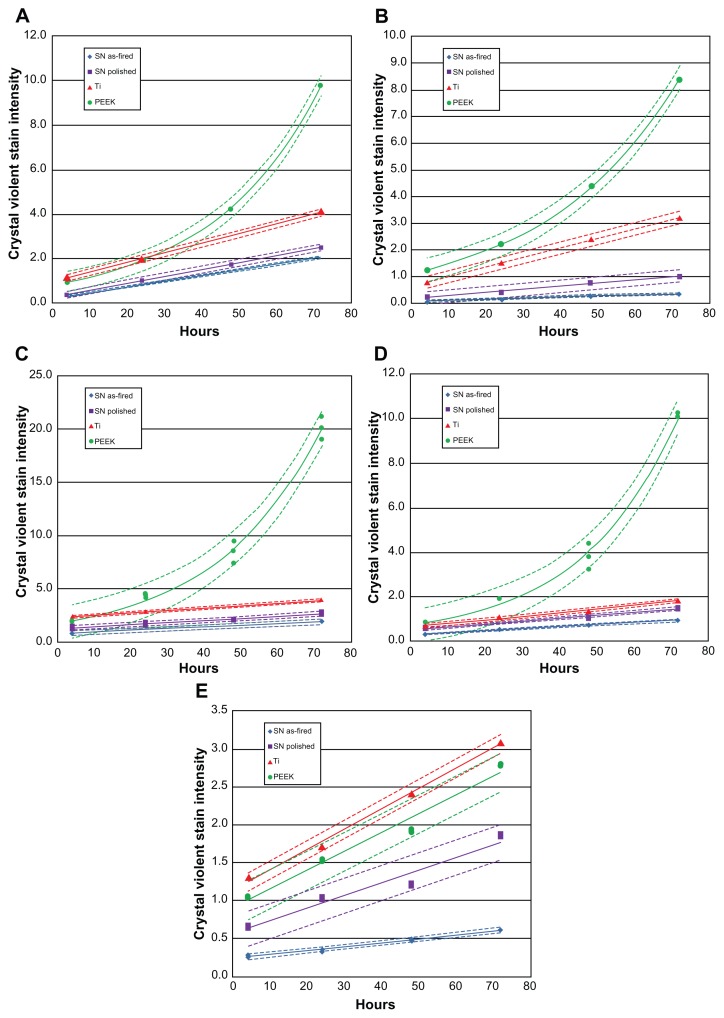

Figure 3 shows biofilm formation for each bacterial species, and Figure 4 shows corresponding live bacteria counts at each time interval. Except for Enterococcus, trends in biofilm formation were similar for all bacteria. Exponential growth of biofilm was noted on PEEK when exposed to S. epidermidis, S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, and E. coli, whereas linear growth was observed for Si3N4 and Ti. Independent of time points, the lowest biofilm formation occurred on the as-fired Si3N4, followed by polished Si3N4. These differences were statistically significant (P < 0.05) for bacterial exposure times > 24 hours. Also, with the exception of Enterococcus, biofilm formation was significantly lower (P < 0.05) on Ti compared with PEEK, for time periods > 48 hours. PEEK demonstrated the highest biofilm affinity, with values that were 5–16 times greater than those for as-fired Si3N4, 1.5–10 times more than for polished Si3N4, and between 1 and 6.7 times higher than for Ti.

Figure 3.

Biofilm formation: (A) Staphylococcus epidermidis, (B) S. aureus, (C) Pseudomonas aeruginosa, (D) Escherichia coli, (E) Enterococcus.

Note: Dashed lines represent confidence intervals at P < 0.05.

Abbreviations: SN, Si3N4; PEEK, poly-ether-ether-ketone.

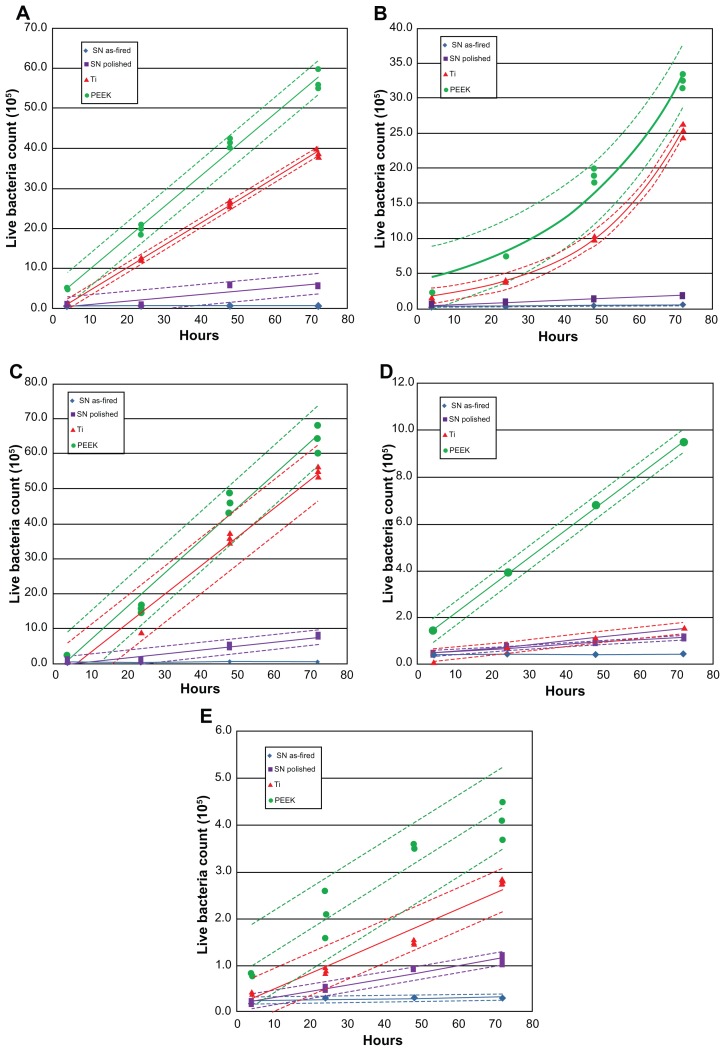

Figure 4.

Count of live bacteria: (A) Staphylococcus epidermidis, (B) S. aureus, (C) Pseudomonas aeruginosa, (D) Escherichia coli, (E) Enterococcus.

Note: Dashed lines represent confidence intervals at P < 0.05.

Abbreviations: SN, Si3N4; PEEK, poly-ether-ether-ketone.

Live bacteria counts were the highest for PEEK at all time periods, followed by Ti, polished Si3N4, and then asfired Si3N4 (Figure 4). These differences were statistically significant (P < 0.05) for all bacterial species tested, and at all time periods > 48 hours. Live bacteria manifested on PEEK were between 8 and 30 times the bacteria found on as-fired Si3N4. These results were particularly remarkable for P. aeruginosa, which is a virulent and difficult microbe to eliminate from polymeric implants.43

To summarize, less bacterial activity was manifested on Si3N4 than on either Ti or PEEK, probably because of the surface chemistry and nanostructure differences between these materials. Substantially lower loads of S. epidermidis, S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, E. coli, and Enterococcus bacteria were measured on Si3N4 surfaces than Ti or PEEK, for up to 72 hours of incubation.

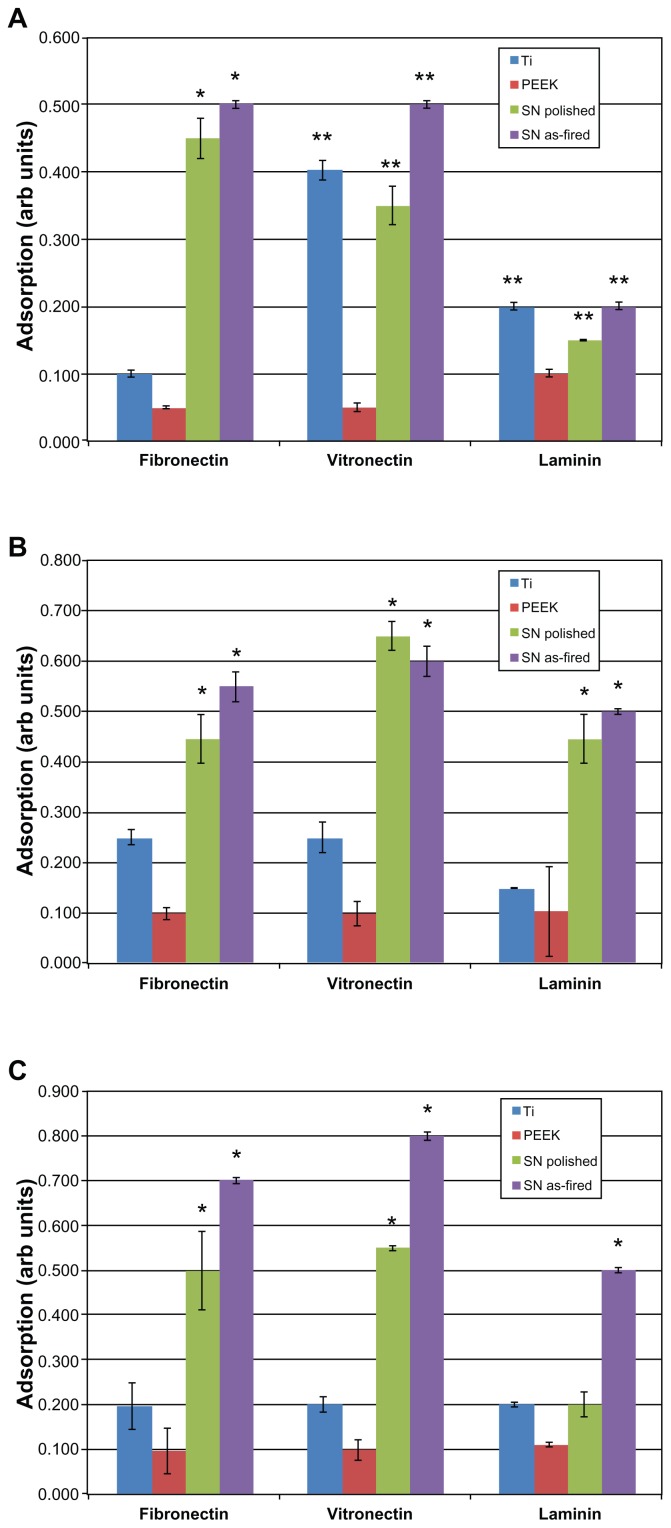

Protein adsorption studies

Figure 5 shows the relative absorbance of fibronectin, vitronectin, and laminin at 20-, 60-, and 240-minute intervals. Fibronectin and vitronectin adsorption was significantly greater on Si3N4 (whether polished or as-fired) when compared with PEEK or Ti at all time intervals (P < 0.01). As-fired Si3N4 showed a higher affinity for these two proteins than polished Si3N4. Laminin adsorption did not differ significantly between the biomaterials at the 20-minute time interval. At 60 minutes, both Si3N4 surfaces showed significant increased laminin adsorption (P < 0.01) when compared with Ti or PEEK. At 240 minutes, as-fired Si3N4 was the only surface that showed statistically more laminin adsorption (P < 0.01) than all other materials.

Figure 5.

Protein adsorption: (A) 20 minutes, (B) 60 minutes, (C) 240 minutes.

Notes: *P < 0.01 compared with all others; **P < 0.05 compared with PEEK.

Abbreviations: Arb, arbitrary; SN, Si3N4; PEEK, poly-ether-ether-ketone.

To summarize, Ti and PEEK proved inferior in terms of protein adsorption when compared with as-fired and polished Si3N4 surfaces. As-fired Si3N4 provided the highest protein adsorption platform among the materials tested. Surface protein adsorption is relevant because previous studies have correlated increased vitronectin and fibronectin adsorption to decreased bacterial activity.35

Discussion

Bacterial infection of orthopedic implants is a complex, multifactorial process that is influenced by bacterial properties, the presence of serum proteins, fluid flow around the implant, implant surface chemistry and morphology, host immune variables, and probably other variables.44 Infection can arise from inadvertent contamination of an implant, contagion from the surgical staff, bacteria arising from the patient’s skin or mucus membranes, unrecognized infection elsewhere in the body, ineffectively applied surgical disinfectants, and sepsis acquired from others.45 Most of these risk factors can be mitigated by appropriate nosocomial hygiene practices, and through the use of perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis.3,6,9,46,47 However, no strategy has proven effective in completely eliminating the risk of infections related to implant surgery. Strategies to discourage bacterial adhesion to implants have included antibacterial surface coatings and treatments, and the development and use of nanostructured surfaces, or a combination of these methods.

Surface coatings and treatments

Surface coatings or surface treatments on implants can resist pathogen adhesion or release chemicals that invade bacterial biofilm. Silver ions have been investigated as a surface antiseptic agent, although the exact mechanism for silver ion toxicity on bacteria is unclear.48 Silver can be incorporated into polymeric or inorganic coatings,48,49 and while its anti-infective properties have been known for generations, it continues to drive patent innovation.50,51 Other coatings have included pre-loaded formulations of antibiotics like vancomycin or gentamicin, or antiseptic agents like chlorohexidine and chloroxylenol.52 Antibacterial polymeric functionalized coatings which incorporate hyaluronic acid and chitosan have been investigated thoroughly.52–57 Xerogel polymers that have been modified to release nitric oxide are effective in inhibiting the adhesion of S. aureus, S. epidermidis, and E. coli.58 A limitation of all such coatings is the transient duration of effectiveness, ie, once the coating dissipates, so does any antibacterial effect.

Surface modifications of biomaterials can provide a long-term shield against bacterial infection of implants. Yoshinari et al modified the surface of Ti and studied bacterial adhesion of P. gingivalis and Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans using ion implantation of Ca+, N+, and F+, ion-beam deposition of Ag, Sn, Zn, and Pt, ion plating of TiN and Al2O3, and anodic oxidation formation of TiO2.59 Control materials included polished, sand-blasted, and striated Ti. They found a general trend toward higher bacterial adhesion on blasted and Ca+ implanted Ti. A follow-up study by these authors also showed that F+ implanted surfaces resisted initial bacterial adhesion in the absence of fluorine leaching from the surface; the antibacterial effect probably related to metal-fluorine complexes at the surface.60 Katsikogianni et al found otherwise: S. epidermidis activity on polymers with and without fluorine showed that those containing fluorine increased bacteria attachment.61 Raulio et al also investigated fluorine, and found that by coating stainless steel with fluoropolymers, it was possible to reduce biofilm formation of several bacteria strains, including S. epidermidis.62

Li et al performed a comparative study using glass and metal-oxides applied as thin films.63 These included three uncoated glass surfaces and combinations of Co-Fe-Cr, Ti-Fe-O, SnO2, SnO2-F, SnO2-Sb, Al2O3, and Fe2O3 thin films applied to glass substrates. After measuring material hydrophilicity, zeta potential, and surface energy, the authors tested them against eight strains of bacteria, and found that hydrophobicity and total surface energy (rather than material chemistry) led to increased bacterial adhesion. Hydrophilic surfaces had the fewest number of adherent bacteria, and increasing the concentration of surface ions encouraged binding for both Gram-positive (Bacillus subtilis) and Gram-negative (two P. aeruginosa strains, three E. coli strains, and two Burkholderia cepacia strains) bacteria.

Conversion of Ti surfaces to TiO2 via anodic oxidation, electrophoretic deposition, chemical vapor deposition, ion implantation, and plasma spraying has been examined as an anti-infective surface modification strategy, especially when coupled with photocatalytic activation of TiO2.64 Orthopedic implants made of porous Ti are commonly coated with hydroxyapatite to promote osteointegration, but this strategy may lead to increased harboring of S. aureus bacteria, more severe infection, and less osteointegration when compared with uncoated Ti.65,66

The results of this present study show that Si3N4 has intrinsic bacteriostatic properties, whether in an as-fired or smooth-surface morphology. This study did not elucidate the precise mechanism of Si3N4 anti-infectivity, but results suggest that material hydrophilicity and surface chemistry may contribute to less biofilm formation (Figure 3) and lower bacteria counts (Figure 4) on Si3N4 when compared with Ti or PEEK. These differences were observed for all bacteria, regardless of Gram-positive or Gram-negative strains. Hydrophilic Si3N4 surfaces were probably less conducive to bacterial adhesion, when compared with hydrophobic surfaces where water displacement is not required for microbial adherence.44 Consistent with this observation, the inert and highly hydrophobic characteristics of PEEK promoted bacterial adhesion and inhibited protein adsorption when compared with Si3N4. Other authors have supported these observations as they relate to PEEK and Ti.67,68

The anti-infectivity of Si3N4 may also relate to surface chemistry, and the authors’ observations are consistent with previous data with polymeric coatings containing chitosan, a material similar to Si3N4 in terms of a net positive charge and the presence of amine groups at the surface.52–56 The interaction of these groups with negatively charged bacteria reportedly leads to membrane disruption and lysis in chitosan-containing polymers.56 However, further research is required to confirm whether or not this is a dominant operative mechanism for Si3N4.

Nanostructured surfaces

Nanotechnology is of interest in enhancing the surface characteristics and improving the performance of orthopedic implants. Increasing micron-level surface roughness of biomedical implants correlates with increased bacterial adhesion44 and enhanced osteointegration.69 The competition between bacteria, bone cells, and serum proteins has been characterized as a “race to the surface.”10 However, surface roughness is only one of several variables that influence bacterial adhesion and protein adsorption on an implant. For instance, without specifically distinguishing changes in surface roughness, surface chemistry, or crystallinity, Truong et al showed that nanoscale roughening of ultrafine grained Ti led to greater attachment of S. aureus and P. aeruginosa, when compared with smooth surfaces.70 Conversely, Singh et al found increased bacterial adhesion and biofilm formation on Ti surfaces with Ra (roughness average) values < 20 nm, and increased protein adsorption at Ra values between 16 and 32 nm; further increases in surface roughness were associated with reduced pathogen activity. 71 In contrast, Hilbert et al could not correlate bacterial adhesion, colonization, and growth with changes in surface finish ranging from 0.1 to 0.90 μm,72 and Flint et al found that bacterial adhesion could not be related to surface roughness at all.73 Thus, surface roughness alone may not fully explain the differences in bacterial adhesion and protein adsorption.

Anselme et al reviewed the factors that affect the interaction of cells and bacteria with nanostructured surfaces. 74 In addition to surface roughness, detailed surface topography, including the size, shape, orientation, distance, and organization of surface nanofeatures were identified as important variables. Whitehead et al further supported this view when they found higher bacterial counts on substrates that contained 2 μm diameter pits as opposed to those in the range of 0.5 μm.75 Xu et al compared bacterial adhesion between two polyurethane surfaces of the same chemistry; one was smooth and the other contained oriented protrusions or pillars (400 nm diameter × 650 nm height).76 They found biofilm formation significantly less for both S. epidermidis and S. aureus when using the highly textured polyurethane. Dalby et al examined the response of fibroblasts to nanocolumn structures (100 nm diameter × 160–170 nm height) in polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) in comparison with smooth substrates and demonstrated decreased cell adhesion using the materials with nanocolumns.77 Bagno et al showed that the number of protruding peaks (ie, peak density) was positively correlated with osteoblast adhesion.78 Similar topographical effects on bacterial adhesion and protein adsorption were observed by these authors for Ti, when conventional (smooth) surfaces were compared to nanoroughened, nanotextured, and nanotubular variations. The authors also reported decreased in-vitro activity of S. aureus, S. epidermidis, and P. aeruginosa on nanorough surfaces prepared by electron-beam evaporation, but an opposite result for nanotubular and nanorough surfaces prepared via anodization.35 However, all three of the nanoprepared Ti surfaces demonstrated increased adsorption of fibronectin in comparison with conventional Ti. A subsequent study showed reduced adhesion of macrophages on anodized Ti with nanotextured and nanotubular structures.79

Engineered surfaces with topographical features in the nanometer range may affect cell behavior while reducing bacterial adhesion, but these factors alone do not sufficiently predict cellular response. Other variables related to surface energy, surface charge, and chemistry can also inhibit bacterial colonization while enhancing protein adsorption and conformation, leading to improved osteoblast adhesion and tissue growth.31–33 Biomaterial surfaces with nanorough features are associated with greater vitronectin and fibronectin adsorption that, in turn, are related to decreased bacterial function on the surface.31–33,35,80

The acicular grain structure on the as-fired surface of Si3N4 is composed of randomly oriented columnar grains that are typically 200–700 nm in diameter, and that can protrude above the surface up to about 3 μm. This as-fired surface is not only significantly rougher than Ti, PEEK, or polished Si3N4 (Table 1) but its nanotopography is fundamentally different, as suggested by AFM surface measurements. Even though the PEEK and titanium samples were as-machined, they had significantly smoother surfaces at the nanolevel than either as-fired or polished Si3N4. Consequently, bacterial and protein adherence to the biomaterials differed in the present experiments. While this study did not elucidate the precise mechanisms, it is probable that the observed behavior of as-fired Si3N4 is related to nanocolumns, protrusions, and peaks described in previous studies for polyurethane, PMMA, and Ti surfaces.76–78 In summary, the present authors believe it is the totality of silicon nitride’s nano-topography – including its protruding acicular grains with their definitive hexagonal features and sharp grain ends – combined with its surface chemistry (ie, positive surface charge and the presence of amine groups) which provides Si3N4 with its unique antibacterial and protein adsorption characteristics.

Conclusion

This study examined the behavior of Ti, PEEK, and Si3N4 when respective materials were exposed to five different bacterial species for up to 72 hours. Polished and as-fired surface formulations of Si3N4 were tested. Decreased biofilm formation and bacterial colonization were demonstrated on both as-fired and polished Si3N4 in comparison with Ti or PEEK, under in-vitro incubation for time periods of up to 72 hours. Si3N4 resisted bacterial proliferation under these conditions, despite the absence of antibiotic pharmaceutical agents. Differential protein adsorption on Ti, PEEK, and Si3N4 surfaces was also demonstrated, such that fibronectin, vitronectin, and laminin adsorbed preferentially onto Si3N4 when compared with Ti or PEEK, for time periods of up to 4 hours. Previous studies have shown that such differences in protein affinity for biomaterial surfaces may explain, at least in part, differences in biomaterial susceptibility to bacterial infection. The unique surface chemistry and nanostructured features of Si3N4 may contribute to the favorable antibacterial properties of this bioceramic material, and support further investigation into the use of Si3N4 as a material platform for orthopedic implants.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Khalid A Sethi, MD, FACS, and Christine Ann Snyder, PA, of the Southern New York NeuroSurgical Group, P.C., for their assistance in performing the studies, and David Bohrer for efforts in initiating this work. The authors also express their appreciation to Bryan McEntire, Chief Technology Officer, Alan Lakshminarayanan PhD, Senior Director of Research and Development, Ryan Bock PhD, Research Scientist, all of Amedica Corporation (Salt Lake City, UT); and Steven C Friedman, Senior Editor, Department of Orthopedic Surgery, University of Missouri, for their kind assistance with the manuscript.

Footnotes

Disclosure

B Sonny Bal is advisory surgeon to Amedica, developer of synthetic silicon nitride for orthopedic applications, and serves on the Board of Directors of Amedica, Salt Lake City, UT. Co-authors Deborah Gorth, Sabrina Puckett, Batur Ercan, Thomas J Webster, and Mohamed N Rahaman have no disclosures for this article.

References

- 1.Rajaee SS, Bae HW, Kanim LE, Delamarter RB. Spinal fusion in the United States: analysis of trends from 1998 to 2008. Spine. 2012;37(1):67–76. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31820cccfb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mendenhall S. Hip and knee implant review. Orthopedic Network News. 2011;22(3):466–469. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collins I, Wilson-MacDonald J, Chami G, et al. The diagnosis and management of infection following instrumented spinal fusion. Eur Spine J. 2008;17(3):445–450. doi: 10.1007/s00586-007-0559-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ong KL, Kurtz SM, Lau E, et al. Prosthetic joint infection risk after total hip arthroplasty in the Medicare population. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24(Suppl 6):105–109. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2009.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kurtz SM, Ong KL, et al. Prosthetic joint infection risk after TKA in the Medicare population. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:52–56. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-1013-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matar WY, Jafari SM, Restrepo C, et al. Preventing infection in total joint arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(Suppl):36–46. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.01046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gardner J, Gioe TJ, Tatman P. Can this prosthesis be saved? Implant salvage attempts in infected primary TKA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(4):970–976. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1417-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kurtz SM, Lau E, Schmier J, et al. Infection burden for hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States. J Arthroplasty. 2008;23(7):984–991. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2007.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Darouiche RO. Treatment of infections associated with surgical implants. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(14):1422–1429. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra035415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gristina AG. Biomaterial-centered infection: microbial adhesion versus tissue integration. Science. 1987;237(4822):1588–1595. doi: 10.1126/science.3629258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moroni A, Vannini F, Mosca M, Giannini S. State of the art review: techniques to avoid pin loosening and infection in external fixation. J Orthop Trauma. 2002;16(3):189–195. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200203000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mahan J, Seligson D, Henry S, Hynes P, Dobbins J. Factors in pin tract infections. Orthopedics. 1991;14(3):305–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zlowodzki M, Prakash JS, Aggarwal NK. External fixation of complex femoral shaft fractures. Int Orthop. 2007;31(3):409–413. doi: 10.1007/s00264-006-0187-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Green S, Ripley M. Chronic osteomyelitis in pin tracks. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984;66(7):1092–1098. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Costerton JW, Stewart PS, Greenberg EP. Bacterial biofilms: a common cause of persistent infections. Science. 1999;284(5418):1318–1322. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5418.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rimondini L, Fini M, Giardino R. The microbial infection of biomaterials: a challenge for clinicians and researchers. A short review. J Appl Biomater Biomech. 2005;3(1):1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fux C, Costerton J, Stewart P, Stoodley P. Survival strategies of infectious biofilms. Trends Microbiol. 2005;13(1):34–40. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Donlan RM. Biofilms and device-associated infections. Emerg Infect Dis. 2001;7(2):277–281. doi: 10.3201/eid0702.010226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baquero F. Gram-positive resistance: challenge for the development of new antibiotics. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;39(Suppl A):1–6. doi: 10.1093/jac/39.suppl_1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Campoccia D, Montanaro L, Arciola CR. The significance of infection related to orthopedic devices and issues of antibiotic resistance. Biomaterials. 2006;27(11):2331–2339. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Webster TJ, Ejiofor JU. Increased osteoblast adhesion on nanophase metals: Ti, Ti6Al4V, and CoCrMo. Biomaterials. 2004;25(19):4731–4739. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Webster TJ, Siegel RW, Bizios R. Osteoblast adhesion on nanophase ceramics. Biomaterials. 1999;20(13):1221–1227. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(99)00020-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Webster TJ, Ergun C, Doremus RH, Siegel RW, Bizios R. Enhanced functions of osteoblasts on nanophase ceramics. Biomaterials. 2000;21(17):1803–1810. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Webster TJ, Ergun C, Doremus RH, Siegel RW, Bizios R. Enhanced osteoclast-like cell functions on nanophase ceramics. Biomaterials. 2001;22(11):1327–1333. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00285-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ejiofor J, Webster T. Bone cell adhesion on titanium implants with nanoscale surface features. Int J Powder Metallurgy. 2004;40(2):43–53. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ward BC, Webster TJ. Increased functions of osteoblasts on nanophase metals. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2007;27(3):575–578. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller DC, Vance RJ, Thapa A, Webster TJ, Haberstroh KM. Comparison of fibroblast and vascular cell adhesion to nano-structured poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) films. Appl Bionics Biomech. 2005;2(1):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cohen A, Liu-Synder P, Storey D, Webster TJ. Decreased fibroblast and increased osteoblast functions on ionic plasma deposited nanostructured Ti coatings. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2007;2(8):385–390. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Puckett S, Pareta R, Webster TJ. Nano rough micron patterned titanium for directing osteoblast morphology and adhesion. Int J Nanomedicine. 2008;3(2):229–241. doi: 10.2147/ijn.s2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yao C, Slamovich EB, Webster TJ. Enhanced osteoblast functions on anodized titanium with nanotube-like structures. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2008;85(1):157–166. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Woo KM, Chen VJ, Ma PX. Nano-fibrous scaffolding architecture selectively enhances protein adsorption contributing to cell attachment. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2003;67(2):531–537. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.10098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khanga D, Kim SY, Liu-Snyder P, et al. Enhanced fibronectin adsorption on carbon nanotube/poly(carbonate) urethane: Independent role of surface nano-roughness and associated surface energy. Biomaterials. 2007;28(32):4756–4768. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Webster TJ, Ergun C, Doremus RH, Siegel RW, Bizios R. Specific proteins mediate enhanced osteoblast adhesion on nanophase ceramics. J Biomed Mater Res. 2000;51(3):475–483. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(20000905)51:3<475::aid-jbm23>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Colon G, Ward BC, Webster TJ. Increased osteoblast and decreased Staphylococcus epidermidis functions on nanophase ZnO and TiO2. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2006;78(3):595–604. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Puckett SD, Taylor E, Raimondo T, Webster TJ. The relationship between the nanostructure of titanium surfaces and bacterial attachment. Biomaterials. 2010;31(4):706–713. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.09.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.2008. ASTM D7334-08 Standard Practice for Surface Wettability of Coatings, Substrates, and Pigments by Advancing Contact Angle Measurement. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brown AM. A step-by-step guide to non-linear regression analysis of experimental data using a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2001;65(3):191–200. doi: 10.1016/s0169-2607(00)00124-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mezzasalma S. Characterization of silicon nitride surface in water and acid environment: a general approach to the colloidal suspensions. J Colloid Interface Sci. 1996;180(2):413–420. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lewis JA. Colloidal processing of ceramics. J Am Ceram Soc. 2000;59(10):2341–2359. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roessler S, Zimmermann R, Scharnweber D. Characterization of oxide layers on Ti6Al4V and titanium by streaming potential and streaming current measurements. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2002;26(4):387–395. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ma J, Wang C, Liang CH. Colloidal and electrophoretic behavior of polymer particulates in suspension. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2007;27(4):886–889. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim S, Baik S. Hot isostatic pressing of sintered silicon nitride. J Am Ceram Soc. 1991;74(7):1735–1738. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barton AJ, Sagers RD, Pitt WG. Bacterial adhesion to orthopedic implant polymers. J Biomed Mater Res. 1996;30(3):403–410. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4636(199603)30:3<403::AID-JBM15>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Katsikogianni M, Missirlis YF. Concise review of mechanisms of bacterial adhesion to biomaterials and of techniques used in estimating bacteria-material interactions. Eur Cell Mater. 2004;8:37–57. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v008a05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rosenthal VD, Maki DG, Jamulitrat S, et al. International Nosocomial Infection Control Consortium (INICC) report, data summary for 2003–2008, issued June 2009. Am J Infect Control. 2010;38(2):95–104. e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zimmerli W, Trampuz A, Ochsner PE. Prosthetic-joint infections. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(16):1645–1654. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra040181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Senthi S, Munro JT, Pitto RP. Infection in total hip replacement: meta-analysis. Int Orthop. 2011;35(2):253–260. doi: 10.1007/s00264-010-1144-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Knetsch MLW, Koole LH. New strategies in the development of antimicrobial coatings: the example of increasing usage of silver and silver nanoparticles. Polymers. 2011;3(1):340–366. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang H-L, Chang Y-Y, Lai M-C, et al. Antibacterial TaN-Ag coatings on titanium dental implants. Surf Coat Technol. 2010;205(5):1636–1641. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ziegler G, Gollwitzer H, Heidenau F, Mitteimeier W, Stenzel F. US Patent 7,906,132. Antiinfectious, biocompatible titanium coating for implants, and method for the production thereof. 2011 Mar 15;

- 51.Neumann H-G, Prinz C. US Patent Application Publication 2012/0024712. Method for producing an anti-infective coating on implants. 2012 Feb 2;

- 52.Zhao L, Chu PK, Zhang Y, Wu Z. Antibacterial coatings on titanium implants. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2009;91(1):470–480. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.31463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hamilton V, Yuan Y, Rigney D, et al. Bone cell attachment and growth on well-characterized chitosan films. Polym Int. 2007;104:641–647. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shi Z, Neoh KG, Kang ET, Poh C, Wang W. Bacterial adhesion and osteoblast function on titanium with surface-grafted chitosan and immobilized RGD peptide. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2008;86(4):865–872. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jou C-H, Yuan L, Lin S, et al. Biocompatibility and antibacterial activity of chitosan and hyaluronic acid immobilized polyester fibers. J Appl Polym Sci. 2007;104:220–225. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ikeda T, Hirayama H, Yamaguchi H, Tazuke S, Watanabe M. Polycationic biocides with pendant active groups: molecular weight dependence of antibacterial activity. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1986;30(1):132–135. doi: 10.1128/aac.30.1.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chua P-H, Neoh K-G, Kang E-T, Wang W. Surface functionalization of titanium with hyaluronic acid/chitosan polyelectrolyte multilayers and RGD for promoting osteoblast functions and inhibiting bacterial adhesion. Biomaterials. 2008;29(10):1412–1421. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Charville G, Hetrick E, Geer C. Reduced bacterial adhesion to fibrinogen-coated substrates via nitric oxide release. Biomaterials. 2008;29(30):4039–4044. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yoshinari M, Oda Y, Kato T, Okuda K, Hirayama A. Influence of surface modifications to titanium on oral bacterial adhesion in vitro. J Biomed Mater Res. 2000;52(2):388–394. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(200011)52:2<388::aid-jbm20>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yoshinari M, Oda Y, Kato T. Influence of surface modifications to titanium on antibacterial activity in vitro. Biomaterials. 2001;22:1–2. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00392-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Katsikogianni M, Spiliopoulou I, Dowling DP, Missirlis YF. Adhesion of slime producing Staphylococcus epidermidis strains to PVC and diamond-like carbon/silver/fluorinated coatings. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2006;17(8):679–689. doi: 10.1007/s10856-006-9678-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Raulio M, Järn M, Ahola J, et al. Microbe repelling coated stainless steel analysed by field emission scanning electron microscopy and physicochemical methods. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2008;35(7):751–760. doi: 10.1007/s10295-008-0343-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li B, Logan BE. Bacterial adhesion to glass and metal-oxide surfaces. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2004;36(2):81–90. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2004.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Visai L, De Nardo L, Punta C, et al. Titanium oxide antibacterial surfaces in biomedical devices. Int J Artif Organs. 2011;34(9):929–946. doi: 10.5301/ijao.5000050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vogely H, Oosterbos C, Puts E, et al. Effects of hydroxyapatite coating on Ti6Al4V implant site infection in a rabbit tibial model. J Orthop Res. 2000;18:485–493. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100180323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Oosterbos C, Vogely H, Nijhof M, et al. Osseointegration of hydroxy-apatiteöcoated and noncoated Ti6Al4V implants in the presence of local infection: a comparative histomorphometrical study in rabbits. J Biomed Mater Res. 2002;60:339–347. doi: 10.1002/jbm.1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Briem D, Strametz S, Schröder K, et al. Response of primary fibroblasts and osteoblasts to plasma treated polyetheretherketone (PEEK) surfaces. J Mater Sci Med. 2005;16(7):671–677. doi: 10.1007/s10856-005-2539-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Olivares-Navarrete R, Gittens R, Schneider J, et al. Osteoblasts exhibit a more differentiated phenotype and increased bone morphogenetic protein production on titanium alloy substrates than on polyether-ether-ketone. Spine J. 2012;12(3):265–272. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schwartz Z, Raz P, Zhao G, et al. Effect of micrometer-scale roughness of the surface of Ti6Al4V pedicle screws in vitro and in vivo. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(11):2485–2498. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.00499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Truong VK, Lapovok R, Estrinb YS, et al. The influence of nano-scale surface roughness on bacterial adhesion to ultrafine-grained titanium. Biomaterials. 2010;31(13):3674–3683. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.01.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Singh AV, Vyas V, Patil R, et al. Quantitative characterization of the influence of the nanoscale morphology of nanostructured surfaces on bacterial adhesion and biofilm formation. PloS One. 2011;6(9):e25029. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hilbert LR, Bagge-Ravn D, Kold J, Gram L. Influence of surface roughness of stainless steel on microbial adhesion and corrosion resistence. Int Biodeterior Biodegradation. 2003;52(3):175–185. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Flint SH, Brooks JD, Bremer PJ. Properties of the stainless steel substrate influencing the adhesion of thermo-resistant streptococci. J Food Eng. 2000;43(4):235–242. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Anselme K, Davidson P, Popa M, et al. The interaction of cells and bacteria with surfaces structured at the nanometre scale. Acta Biomater. 2010;6(10):3824–3846. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Whitehead KA, Colligon J, Verran J. Retention of microbial cells in substratum surface features of micrometer and sub-micrometer dimensions. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2005;41(2–3):129–138. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Xu L-C, Siedlecki C. Submicron-textured biomaterial surface reduces staphylococcal bacterial adhesion and biofilm formation. Acta Biomater. 2012;8(1):72–81. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dalby MJ, Riehle MO, Sutherland DS, Agheli H, Curtis ASG. Fibroblast response to a controlled nanoenvironment produced by colloidal lithography. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2004;69(2):314–322. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bagno A, Genovese M, Luchini A, et al. Contact profilometry and correspondence analysis to correlate surface properties and cell adhesion in vitro of uncoated and coated Ti and Ti6Al4V disks. Biomaterials. 2004;25(12):2437–2445. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rajyalakshmi A, Ercan B, Balasubramanian K, Webster TJ. Reduced adhesion of macrophages on anodized titanium with select nanotube surface features. Int J Nanomedicine. 2011;6:1765–1771. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S22763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Anagnostou F, Debet A, Pavon-Djavid G, et al. Osteoblast functions on functionalized PMMA-based polymers exhibiting Staphylococcus aureus adhesion inhibition. Biomaterials. 2006;27(21):3912–3919. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]