Abstract

Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) oxygenates arachidonic acid and the endocannabinoids 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) and arachidonoylethanolamide (AEA). We recently reported that (R)-profens selectively inhibit endocannabinoid oxygenation but not arachidonic acid oxygenation. In this work, we synthesized achiral derivatives of five profen scaffolds and evaluated them for substrate-selective inhibition using in vitro and cellular assays. The size of the substituents dictated the inhibitory strength of the analogs, with smaller substituents enabling greater potency but less selectivity. Inhibitors based on the flurbiprofen scaffold possessed the greatest potency and selectivity, with desmethylflurbiprofen (3a) exhibiting an IC50 of 0.11 μM for inhibition of 2-AG oxygenation. The crystal structure of desmethylflurbiprofen complexed to mCOX-2 demonstrated a similar binding mode to other profens. Desmethylflurbiprofen exhibited a half-life in mice comparable to that of ibuprofen. The data presented suggest that achiral profens can act as lead molecules toward in vivo probes of substrate-selective COX-2 inhibition.

Keywords: Substrate-selective, COX-2, (R)-profens, endocannabinoids, prostaglandins

Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) is a molecular target for nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). It generates prostaglandin-H2 (PGH2), PGH2-glyceryl ester (PGH2-G), and PGH2-ethanolamide (PGH2-EA) from arachidonic acid (AA) and the endocannabinoids 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) and arachidonoylethanolamide (AEA), respectively (Figure S1 of the Supporting Information).1,2 Metabolism of PGH2 generates PGs that function in inflammation, vascular homeostasis, and gastric cytoprotection.3,4 The biological functions of the PG derivatives of PGH2-Gs and PGH2-EAs are largely unknown, but they have been implicated in unique roles in macrophages, tumor cells, and neurons.5,6 In addition to serving as precursors to PG esters and amides, 2-AG and AEA act as agonists of the cannabinoid (CB1 and CB2) receptors.7 CB1 receptors have primarily been studied for the analgesic, locomotor, and temperature regulatory effects. Additionally, CB1 and CB2 receptors are involved in neuroprotection, modulation of inflammation, and carcinogenesis.8−10 Thus, COX-2 oxygenation of 2-AG and AEA may lower cannabinoid tone by reducing the concentrations of endocannabinoids and may generate new bioactive lipids by increasing the concentrations of PG esters and amides.11,12

Our laboratory discovered that rapid, reversible inhibitors of COX-2, such as ibuprofen and mefenamic acid, are significantly more potent inhibitors of 2-AG and AEA oxygenation than AA oxygenation.13 These “substrate-selective” inhibitors bind in one active site of the COX-2 homodimer and alter the structure of the second active site so that 2-AG and AEA oxygenation is inhibited but AA oxygenation is not.14,15 Inhibition of AA oxygenation requires rapid, reversible inhibitors to bind in both active sites. Inhibitor binding in the second active site requires much higher concentrations than binding in the first active site, which gives rise to the phenomenon of substrate-selective inhibition. More recent work from our laboratory has shown that (R)-enantiomers of the arylpropionic acid (profen) class of NSAIDs, which were considered to be inactive as COX inhibitors, are substrate-selective.16

Our goal is to develop an in vivo probe to determine the effects of blocking 2-AG and AEA, but not AA, oxygenation by COX-2. The (R)-profens are active in vitro and in intact cells but undergo unidirectional inversion to the (S)-enantiomers (which inhibit AA oxygenation) in vivo. The degree of inversion varies between species, with humans and rats subject to less inversion than that seen in mice;17 this enantiomerization is an enzymatic process proceeding through an acyl coenzyme A thioester intermediate.18 One approach to eliminate the observed inversion is to synthesize profen derivatives that lack a stereocenter. Herein, we describe the synthesis and in vitro evaluation of achiral NSAIDs based on five profen scaffolds that exhibit substrate-selective behavior (i.e., flurbiprofen, naproxen, ketoprofen, fenoprofen, and ibuprofen), with the most potent and substrate-selective inhibitors being further examined in activated RAW264.7 cells and evaluated for stability in animal models.16,19,20

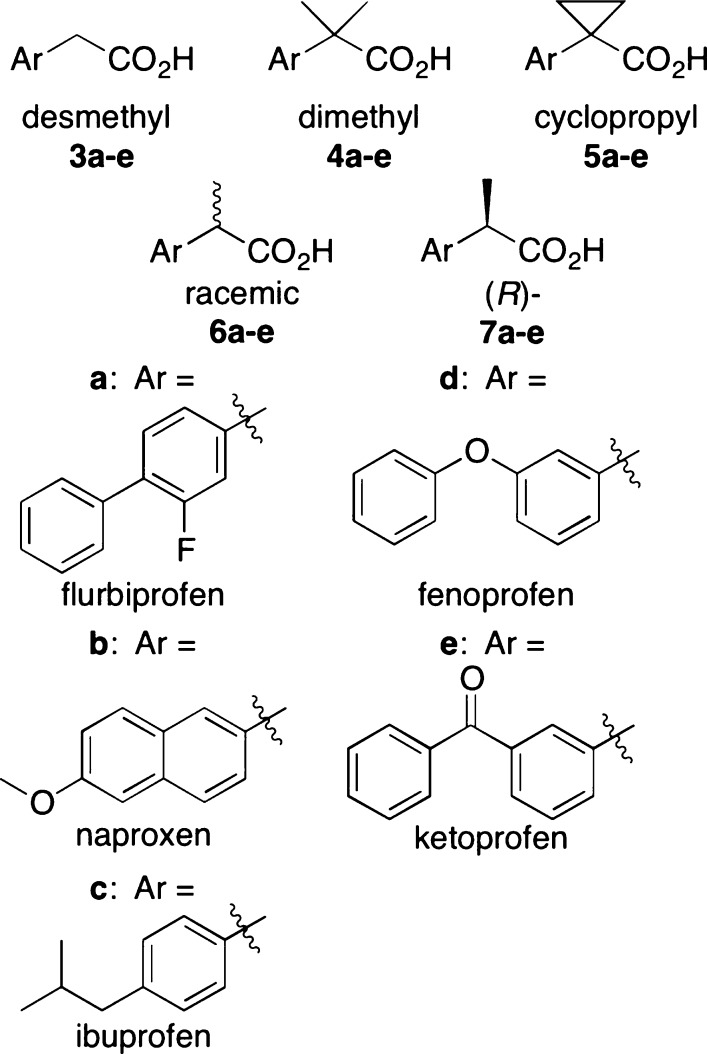

We synthesized three achiral derivatives of each profen scaffold by altering the substitution pattern at the methyl-bearing stereocenter to contain a desmethyl (two hydrogens), dimethyl (two methyls), or cyclopropyl (two methylenes) group (Figure 1). The synthetic route is outlined in Scheme 1 and described in detail in the Supporting Information.

Figure 1.

α-Substituents of desmethyl (3a–e), dimethyl (4a–e), cyclopropyl (5a–e), racemic (6a–e) and (R)- (7a–e) profens. Aryl scaffolds of flurbiprofen (a), naproxen (b), ibuprofen (c), fenoprofen (d), and ketoprofen (e).

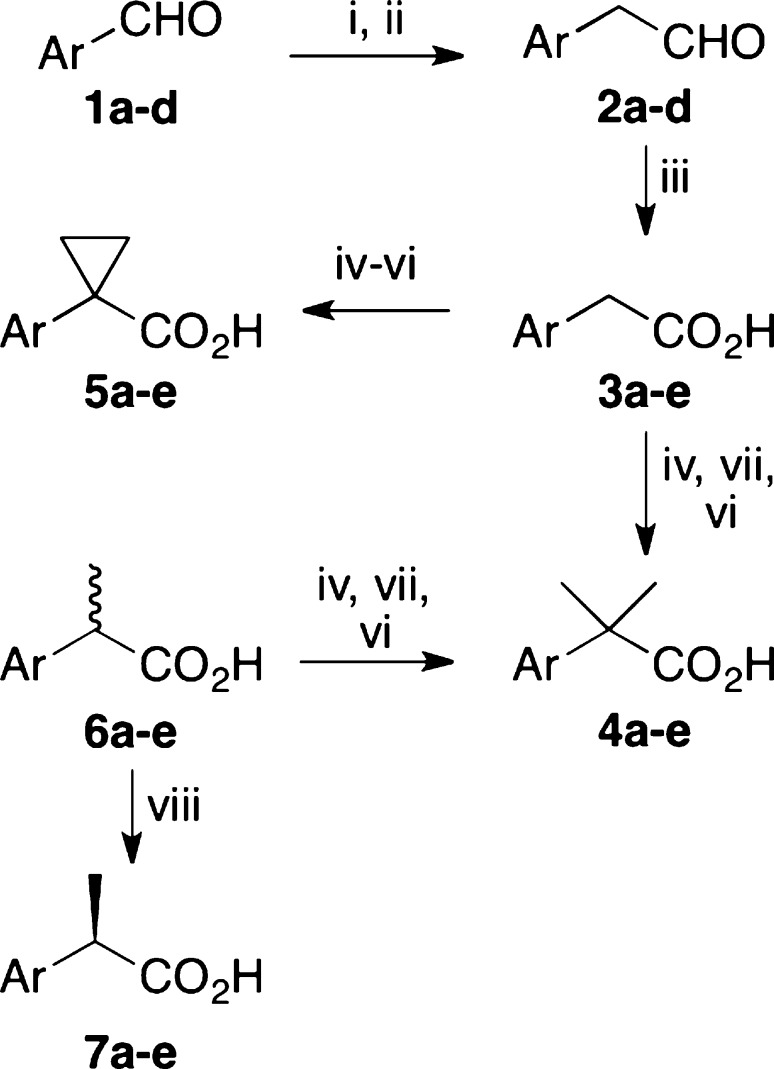

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Achiral Profens.

Reagents and conditions: (i) Ph3P = CHOMe, t-BuOK, THF, 0 °C, 45 min, rt, 1 h. (ii) 5:2 THF/5 N HCl, reflux, 1 h. (iii) 2,3-methylbutene, KH2PO4, NaClO2, 1:1 t-BuOH:H2O, 40 min, rt. (iv) H2SO4, MeOH, reflux, 2 h. (v) LDA, THF, 30 min, −78 °C, HMPA, 30 min, 0 °C, 1,2-dibromoethane, 30 min, rt. (vi) KOTMS, THF, reflux, 2 h. (vii) LDA, THF, 30 min, −78 °C, HMPA, 30 min, 0 °C, iodomethane, 30 min, rt. (viii) Chiralcel AD column, 90:10 hexane/IPA, 0.1% TFA.

Compounds 3a–e, 4a–e, and 5a–e were tested for their ability to inhibit the COX-2-dependent oxygenation of 2-AG and AA in vitro using a previously described method.16 The IC50 value for 2-AG oxygenation was determined for each compound. Since none of the compounds potently inhibited AA oxygenation, percent inhibition was determined at the highest concentration employed. Several interesting observations can be made from the data (Table 1). First, it appears that inhibition of 2-AG oxygenation is dependent on the size of the substituents on the α-carbon, with smaller groups exhibiting higher potency. In general, desmethylprofens, 3a–e, had lower 2-AG IC50 values than the dimethyl and cyclopropylprofens, 4a–e and 5a–e, respectively. Profens 4a–e and 5a–e possessed approximately equivalent IC50 values against 2-AG, reflecting their similar steric bulk. Second, regardless of the substitution on the α-carbon, flurbiprofen derivatives exhibited the lowest 2-AG IC50 values compared to the other profen scaffolds in the same class; these data are consistent with previous observations with α-methyl analogs.16 Flurbiprofen derivative 3a has a 2-AG IC50 value of 0.11 μM, significantly lower than the next best achiral inhibitor, 3e (0.5 μM). The ketoprofen scaffold was the next most potent, followed by the naproxen and then fenoprofen scaffolds. The achiral ibuprofen derivatives were the weakest inhibitors of 2-AG oxygenation, with the best ibuprofen-based inhibitor, 3c, possessing a relatively weak 2-AG IC50 value of 5.5 μM. Third, the flurbiprofen scaffold offers the best substrate selectivity of the scaffolds evaluated. Each flurbiprofen derivative had lower or equal inhibition of AA oxygenation than the other derivatives in each class while also having a lower IC50 for 2-AG. Finally, while every achiral compound besides 5a showed some inhibition of AA oxygenation, the desmethyl class of compounds was the only class where each inhibitor displayed greater than 5% AA inhibition. Within this class it appears that the gains in potency of 2-AG inhibition come at a cost of substrate selectivity.

Table 1. Inhibition of mCOX-2 Dependent Oxygenation of 2-AG and AA by Achiral Profens in Vitroa.

| compd | 2-AG IC50 (μM)b | AA % inhibitionc |

|---|---|---|

| 3a | 0.11 ± 0.02 | 7 ± 11 |

| 3b | 1.4 ± 0.4 | 16 ± 12 |

| 3c | 5.5 ± 0.8 | 14 ± 13 |

| 3d | 6.1 ± 0.5 (68%) | 24 ± 10 |

| 3e | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 10 ± 16 |

| 4a | 1.1 ± 0.4 | 5 ± 11 |

| 4b | – (12%) | 7 ± 11 |

| 4c | – (5%) | 5 ± 14 |

| 4d | 7.3 ± 0.5 (65%) | 17 ± 14 |

| 4e | 3.0 ± 1.2 | 32 ± 6 |

| 5a | 2.3 ± 1.2 (87%) | 0 ± 18 |

| 5b | 3.4 ± 1.2 (77%) | 6 ± 12 |

| 5c | – (45%) | 10 ± 9 |

| 5d | 5.0 ± 0.8 | 15 ± 10 |

| 5e | 4.1 ± 1.4 (75%) | 10 ± 20 |

IC50 values were determined by incubating five concentrations of inhibitor and a solvent control in DMSO with purified murine COX-2 (40 nM) for 3 min followed by addition of 2-AG or AA (5 μM) at 37 °C for 30 s.

Mean ± standard deviation (n = 6); dash (−) indicates <50% inhibition of 2-AG oxygenation at 10 μM inhibitor. Numbers in parentheses indicate maximum inhibition (when not equal to 100%) at 10 μM inhibitor.

% inhibition of AA oxygenation measured at 10 μM inhibitor. Mean ± standard deviation (n = 6).

Expanding upon our previous work with (R)-profens, 7a–c, we resolved the enantiomers of racemic fenoprofen and ketoprofen to determine their ability to act as substrate-selective inhibitors in our in vitro assay.16 (R)-Fenoprofen (7d) and (R)-ketoprofen (7e) possessed weak inhibitory effects on both 2-AG and AA oxygenation (Table S1). (S)-Fenoprofen and (S)-ketoprofen exhibited 2-AG IC50 and percent AA inhibition values similar to those of racemic fenoprofen (6d) and ketoprofen (6e), respectively. These data suggest that the activity of the racemates originate from their (S)-enantiomers and demonstrate that a (R)-profen scaffold does not guarantee substrate selectivity.

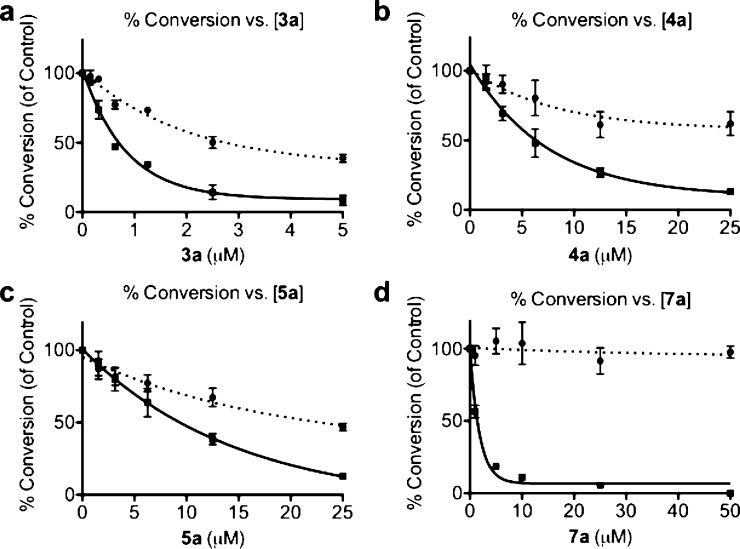

Flurbiprofen derivatives 3a, 4a, 5a, and 7a were evaluated for their ability to selectively inhibit COX-2 dependent oxygenation of 2-AG over AA in intact cells (Figure 2). RAW 264.7 macrophages were stimulated with lipopolysaccharide and interferon γ to generate endogenous sources of AA and 2-AG. Two hours after stimulation, varying doses of inhibitor were added to the cell media, and 6 h after stimulation, the media were collected and analyzed by LC-MS-MS for prostaglandin levels. The 2-AG IC50 values in RAW cells for each achiral compound were 5-fold higher than the values found in the in vitro studies, while 7a displayed a 20-fold increase. Although <10% inhibition of AA oxygenation was observed for each achiral flurbiprofen derivative in vitro, significant inhibition was observed in RAW cells (60% AA inhibition for 3a, 40% for 4a, 55% for 5a). Of particular interest was the observation of AA inhibition by 5a, the only achiral derivative not to exhibit AA inhibition with purified COX-2. Differences in substrate selectivity between in vitro and cell-based assays may be due to differences in the substrate concentration in cells compared to in an in vitro assay.21 The concentration of AA in the microenvironment surrounding COX-2 molecules in cell membranes is unknown, but it may be lower than the concentrations used in our in vitro assay (5 μM).

Figure 2.

Oxygenation of 2-AG and AA vs inhibitor concentration in RAW 264.7 cells. The dotted lines describe the percent conversion of AA to PGE2/PGD2, and the solid lines describe the percent conversion of 2-AG to PGE2-G/PGD2-G. (a) Inhibitor 3a. 2-AG IC50 = 0.6 μM, 60% AA inhibition at 5 μM inhibitor. (b) Inhibitor 4a. 2-AG IC50 = 5.2 μM, 40% AA inhibition at 25 μM inhibitor. (c) Inhibitor 5a. 2-AG IC50 = 10.2 μM, 55% AA inhibition at 25 μM inhibitor. (d) Inhibitor 7a. 2-AG IC50 = 1.3 μM, 0% AA inhibition at 50 μM inhibitor.

We evaluated the pharmacokinetic properties of the two most potent and selective profens screened to date, 3a and 7a, in C57BL/6 mice. Animals (n = 4) received intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections of 10 mg/kg 3a or 7a in 4% DMSO/2% Tween 80 in saline at 0, 8, 24, 32, 48, and 56 h, with blood collected at 72 h. Plasma was analyzed for the dosed compound and, in the case of 7a, its stereoinversion product ((S)-flurbiprofen). When compared to 7a, 3a appeared to exhibit less metabolic stability. Sixteen hours after the last injection, 3a was not detected in mouse plasma, whereas 7a gave an average plasma concentration of 20 μM. The concentration of the stereoinversion product was 31 μM.

Mice underwent acute dosing of 3a at shorter time points to better estimate the compound’s half-life in mouse plasma. Blood samples were collected at 1, 2, and 4 h after a single injection. Analysis of the resultant plasma levels revealed that the 1 h time point had an average 3a plasma concentration of 68 μM (n = 3) followed by concentrations of 50 (n = 2) and 6 μM (n = 3) at the 2 and 4 h time points, respectively. These data suggest that 3a possesses a half-life similar to that of ibuprofen (t1/2 ≈ 2–3 h).22

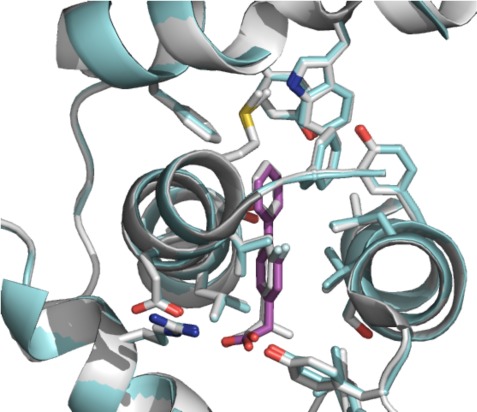

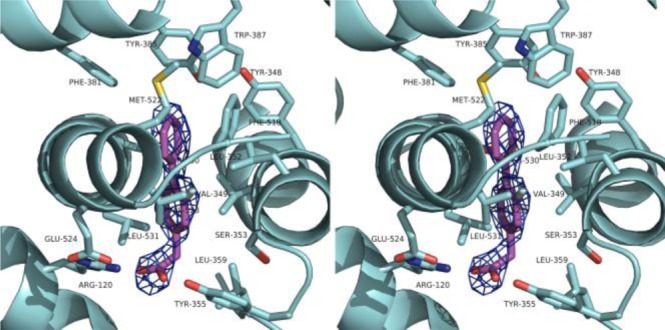

We utilized X-ray crystallography to study the interaction between achiral profens and COX-2. A complex of mCOX-2 and 3a, using a previously described crystallization procedure, diffracted to 2.81 Å (Figure 3, Table S2).16 The carboxylic acid of the ligand forms salt bridges with Arg-120 and Tyr-355. The biphenyl moiety of 3a is deeply buried into the hydrophobic channel and interacts with several residues, such as Val-349, Phe-381, Trp-387, Phe-518, Met-522, Val-523, and Leu-531.

Figure 3.

Stereodiagram of 3a in the active site of mCOX-2 (PDB: 4FM5). 3a is shown in magenta sticks while the interacting residues are presented in cyan sticks. The simulated annealing omit map (Fo – Fc) is contoured at 3σ as blue mesh in the vicinity of 3a.

When the crystal structures of (R)-flurbiprofen and 3a bound to mCOX-2 are overlaid, the two profens have the same general binding orientation in the mCOX-2 active site (0.24 Å rmsd, Figure S2). This orientation allows for the formation of a salt bridge with Arg-120, an interaction crucial for binding.16,23 Establishing the salt bridge with Arg-120 requires the carboxylic acid and α-carbon stereocenter of flurbiprofen to bind near the constriction site of the COX-2 binding pocket, a sterically congested region. Relief of this congestion is likely responsible for the increased inhibition of 2-AG oxygenation upon introduction of smaller substituents at the flurbiprofen α-carbon. Yet, there is a trade-off between potency and selectivity. Comparing the RAW cell data of 3a and 7a suggests that reducing the steric bulk at the α-carbon (i.e., converting the α-methyl group of 7a into the hydrogen present in 3a) increases potency for 2-AG and AA inhibition, resulting in less substrate selectivity. There appear to be favorable interactions promoting substrate selectivity that the more sterically demanding 7a can utilize, but are unavailable to the smaller 3a. The identity of these interactions remains unclear.

The data presented here lead us to several conclusions about achiral profen COX-2 inhibitors. First, achiral profens demonstrate substrate-selective behavior in vitro and in a cellular setting. Second, smaller α-carbon substituents (i.e., hydrogens) result in more potent but less selective inhibitors than more sterically demanding groups (i.e., dimethyl, cyclopropyl). Finally, inhibitor potency and selectivity are dependent on the profen’s aryl scaffold, with some scaffolds (e.g., flurbiprofen) offering superior behavior relative to others (e.g., ibuprofen). In addition, our most potent compound, desmethylflurbiprofen (3a), possesses metabolic stability on par with that of ibuprofen. These results indicate that achiral profens can act as lead molecules for further development toward in vivo probes of substrate-selective COX-2 inhibition.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Kebreab Ghebreselasie for generating the enzyme used for in vitro assays.

Supporting Information Available

Complete assay and synthetic procedures, crystallization data, and analytical and spectral characterization of synthesized compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

This work was supported by grants from the U.S. National Institutes of Health, the National Center for Research Resources, the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, the Department of Energy and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. See the Supporting Information for grant numbers and additional funding information.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Turini M. E.; DuBois R. N. Cyclooxygenase-2: A Therapeutic Target. Annu. Rev. Med. 2002, 53, 35–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouzer C. A.; Marnett L. J. Endocannabinoid Oxygenation by Cyclooxygenases, Lipoxygenases, and Cytochromes P450: Cross-Talk between the Eicosanoid and Endocannabinoid Signaling Pathways. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111105899–5921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funk C. D. Prostaglandins and Leukotrienes: Advances in Eicosanoid Biology. Science 2001, 298, 1871–1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouzer C. A.; Marnett L. J. Cyclooxygenases: Structural and Functional Insights. J. Lipid Res. 2009, April Supplement, S29–S34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward D. F.; Carling R. W. C.; Cornell C. L.; Fliri H. G.; Martos J. L.; Pettit S. N.; Liang Y.; Wang J. W. The pharmacology and therapeutic relevance of endocannabinoid derived cyclo-oxygenase (COX)-2 products. Pharmacol. Ther. 2008, 120171–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sang N.; Zhang J.; Chen C. COX-2 oxidative metabolite of endocannabinoid 2-AG enhances excitatory glutamatergic synaptic transmission and induces neurotoxicity. J. Neurochem. 2007, 10261966–1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svizenska I.; Dubovy P.; Sulcova A. Cannabinoid Receptors 1 and 2 (CB1 and CB2), their Distribution, Ligands and Functional Involvement in the Nervous System Structures—A Short Review. Pharmacol., Biochem. Behav. 2008, 90, 501–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomura D. K.; Morrison B. E.; Blankman J. L.; Long J. Z.; Kinsey S. G.; Marcondes M. C. G.; Ward A. M.; Hahn Y. K.; Lichtman A. H.; Conti B.; Cravatt B. F. Endocannabinoid Hydrolysis Generates Brain Prostaglandins That Promote Neuroinflammation. Science 2011, 3346057809–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D.; Wang H.; Ning W.; Backlund M. G.; Dey S. K.; DuBois R. N. Loss of Cannabinoid Receptor 1 Accelerates Intestinal Tumor Growth. Cancer Res. 2008, 68156468–6476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler C. J.; Rojo M. L.; Rodriguez-Gaztelumendi A. Modulation of the endocannabinoid system: Neuroprotection or neurotoxicity?. Exp. Neurol. 2010, 224137–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda N.; Tsuboi K.; Uyama T.; Ohnishi T. Biosynthesis and degradation of the endocannabinoid 2-arachidonoylglycerol. BioFactors 2011, 3711–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozak K. R.; Crews B. C.; Ray J. L.; Tai H.-H.; Morrow J. D.; Marnett L. J. Metabolism of Prostaglandin Glycerol Esters and Prostaglandin Ethanolamides in Vitro and in Vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 2764036993–36998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prusakiewicz J. J.; Duggan K. C.; Rouzer C. A.; Marnett L. J. Differential Sensitivity and Mechanism of Inhibition of COX-2 Oxygenation of Arachidonic Acid and 2-Arachidonoylglycerol by Ibuprofen and Mefenamic Acid. Biochemistry 2009, 48317353–7355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong L.; Vecchio A. J.; Sharma N. P.; Jurban B. J.; Malkowski M. G.; Smith W. L. Human Cyclooxygenase-2 Is a Sequence Homodimer That Functions as a Conformational Heterodimer. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 2862119035–19046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimon G.; Sidhu R. S.; Lauver D. A.; Lee J. Y.; Sharma N. P.; Yuan C.; Frieler R. A.; Trievel R. C.; Lucchesi B. R.; Smith W. L. Coxibs interfere with the action of aspirin by binding tightly to one monomer of cyclooxygenase-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2010, 107128–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duggan K. C.; Hermanson D. J.; Musee J.; Prusakiewicz J. J.; Scheib J. L.; Carter B. D.; Banerjee S.; Oates J. A.; Marnett L. J. (R)-Profens are substrate-selective inhibitors of endocannabinoid oxygenation by COX-2. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2011, 711803–809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leipold D. D.; Kantoci D.; Murray E. D.; Quiggle D. D.; Wechter W. J. Bioinversion of (R)-flurbiprofen to (S)-flurbiprofen at various dose levels in rat, mouse, and monkey. Chirality 2004, 166379–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodman T. J.; Wood P. J.; Thompson A. S.; Hutchings T. J.; Steel G. R.; Jiao P.; Threadgill M. D.; Lloyd M. D. Chiral inversion of 2-arylpropionyl-CoA esters by human alpha-methylacyl-CoA racemase 1A (P504S) - a potential mechanism for the anti-cancer effects of ibuprofen. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 7332–7334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ossipov M. H.; Jerussi T. P.; Ren K.; Sun H.; Porreca F. Differential effects of spinal (R)-ketoprofen and (S)-ketoprofen against signs of neuropathic pain and tonic nociception: evidence for a novel mechanism of action of (R)-ketoprofen against tactile allodynia. Pain 2000, 872193–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davie I. T.; Slawson K. B.; Burt R. A. P. A Double-Blind Comparison of Parenteral Morphine, Placebo, and Oral Fenoprofen in Management of Postoperative Pain. Anesth. Analg. 1982, 61121002–1005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blobaum A. L.; Marnett L. J. Molecular Determinants for the Selective Inhibition of Cyclooxygenase-2 by Lumiracoxib. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 2822216379–16390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rainsford K. Ibuprofen: pharmacology, efficacy and safety. Inflammopharmacology 2009, 176275–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya D. K.; Lecomte M.; Rieke C. J.; Garavito R. M.; Smith W. L. Involvement of Arginine 120, Glutamate 524, and Tyrosine 355 in the Binding of Arachidonate and 2-Phenylpropionic Acid Inhibitors to the Cyclooxygenase Active Site of Ovine Prostaglandin Endoperoxide H Synthase-1. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 27142179–2184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.