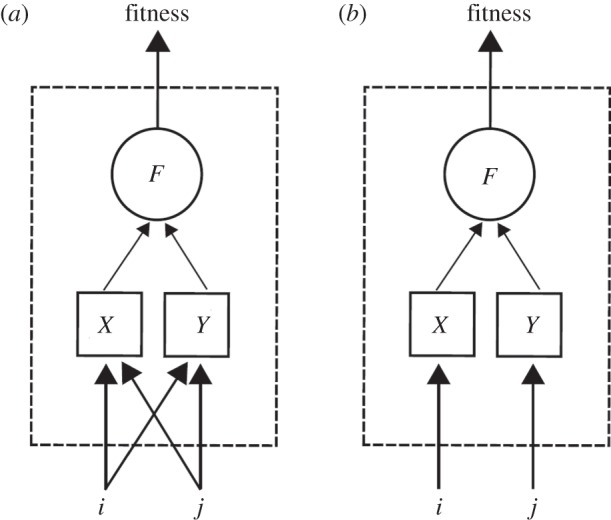

Figure 1.

Schematic depiction of how we quantify epistasis relative to a fitness function that depends on two quantitative traits, or phenotypes. (a) Two alleles or genetic perturbations i and j are assumed to potentially affect multiple traits, here X and Y (‘low-level traits’). The phenomenon in which a genetic perturbation affects multiple traits is called pleiotropy. Here we assume that there is no epistasis at the level of the individual traits X and Y. A ‘high-level trait’ (e.g. fitness f) is defined as a function F of the two traits X and Y. These assumptions allow us to predict how the functional shape of F affects epistasis between the two perturbations. Without any knowledge of this internal structure (dashed box), the presence of epistasis could only be measured experimentally, but not inferred mathematically. (b) The same model as described above, in the absence of pleiotropy. In this case, perturbations i and j affect each a single trait, i.e. X and Y respectively, and can be thought of acting on different modules. Depending on the function F, this may still lead to epistasis.