Abstract

The developing limb has served as an excellent model for studying pattern formation and signal transduction in mammalians. Many of the crucial genes that regulate growth and patterning of the limb following limb bud formation are now well known. However, details regarding the control of limb initiation and early stages of outgrowth remain to be defined. This report is focused on genetic events that pave the way for the establishment of a hindlimb bud. Fgf10 and Tbx are crucial for early phases of limb bud initiation. Here we show that in the absence of Isl1 or of Ldb1/2 there is no hindlimb bud development. Fgf10 expression in the bud mesenchyme is dependent on Isl1 and its Ldb co-regulators. Thus, Isl1 and the Ldb co-regulators of transcription are essential early determinants of mouse limb development. Isl1/Ldb complexes regulate Fgf10 to orchestrate the earliest stages of hindlimb formation.

Introduction

Following gastrulation, paraxial, intermediate and lateral plate segments arise and migrate out of the mesoderm of the primitive streak. Limbs develop from cells of the lateral plate mesoderm (Capdevila and Izpisua Belmonte, 2001; Zeller et al., 2009). These cells form bulges underneath the ectoderm and establish the limb-forming regions that are set within a precisely coordinated expression pattern of members of the family of Hox genes (Burke et al., 1995). Tbx transcription factors are essential for the specification of limb identity. Tbx4 is associated with hindlimb development (Gibson-Brown et al., 1996), while Tbx5 acts in development of the forelimb (Chapman et al., 1996). Following Tbx expression, Fgf10 is expressed in the lateral plate mesoderm of the prospective limb bud mesenchyme. In vitro analysis has identified Fgf10 as a direct target of Tbx5 (Agarwal et al., 2003). Fgf10 is essential both for limb bud initiation and for maintaining outgrowth (Ohuchi et al., 1997; Min et al., 1998; Sekine et al., 1999). Loss of Fgf10 function abrogates hindlimb and forelimb development (Min et al., 1998; Sekine et al., 1999). Fgf10 induces the expression of Fgf8 in the ectoderm. The outgrowth and development of the vertebrate limb bud depends on reciprocal interactions between Fgf10 in the mesenchyme and a group of Fgf signals, including Fgf4, Fgf8 and Fgf17, in the overlying apical ectodermal ridge (AER) (Crossley et al., 1996; Vogel et al., 1996; Ohuchi et al., 1997; Lewandoski et al., 2000; Moon and Capecchi, 2000; Sun et al., 2002).

Several members of the LIM-homeobox (Lhx) gene family of transcription factors are essential for limb development. Earlier studies had shown that the Lhx genes Lhx2, Lhx9 and Lmx1b play key roles in limb patterning and outgrowth (Cohen et al., 1992; Diaz-Benjumea and Cohen, 1993; Ng et al., 1996). Early limb bud formation is accompanied by the expression of Lhx2 and Lhx9. Isl1, an additional Lhx gene, is expressed specifically in the early hindlimb bud of the mouse embryo, with a peak of high level of expression at E9.5 that declines rapidly during the following 24 hrs of limb bud development (Sun et al., 2007; Tzchori et al., 2009). Simultaneous ablation of the partially redundant Lhx2 and Lhx9 genes leads to severe impairment of limb development which is further exacerbated by the simultaneous knockdown of the essential Ldb1 co-regulator of Lhx gene activity in the limb bud mesenchyme (Tzchori et al., 2009). In the present study, we analyzed the role of the Lhx transcriptional machinery during the initiation of limb development in the mesenchyme of the emerging limb bud. We show that the Ldb1-Isl1 complex is essential for hindlimb development and acts upstream of Fgf10 in the limb bud mesenchyme. This is in agreement with recent findings by Kawakami et al. (Kawakami et al., 2011) who showed that Isl1 regulates hindlimb initiation upstream of Fgf10.

Results and Discussion

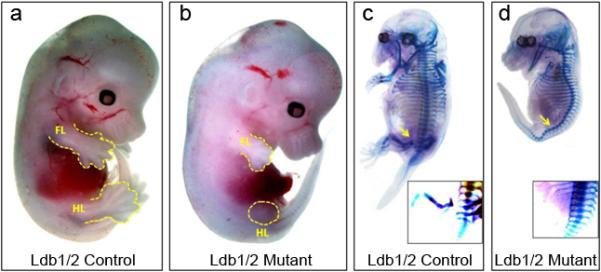

Our analysis has been facilitated by the fact that Ldb1 and Ldb2, the obligatory co-regulators of Lhx gene activity, are expressed during limb bud development (Tzchori et al., 2009). All genetic and molecular analyses to date support the idea that Ldb1 and Ldb2 proteins are functionally redundant, with Ldb1 showing higher expression levels throughout the embryo. Ldb2 null mice are fertile and phenotypically normal, whereas Ldb1 null embryos die shortly after implantation (Mukhopadhyay et al., 2003). To completely ablate Ldb activity in the developing limb, we resorted to conditional inactivation of Ldb1 in an Ldb2 null background (table 1). Floxed Ldb1 (Tzchori et al., 2009) was inactivated in the limb bud mesenchyme by crossing in a T-Cre transgene that is expressed in the mesoderm emanating from the primitive streak, the source of the limb bud mesenchyme (Perantoni et al., 2005; Verheyden et al., 2005). The resulting mutant embryos did not develop beyond E14.5. Mutants were collected at specific stages of early limb development. In the control embryos, hindlimb buds become discernible at E10. In the Ldb1/2 double mutants we failed to observe hindlimb development at this stage. There was no hindlimb bud at E14.5 either, thereby excluding the possibility that development was just delayed. Forelimb bud formation was not affected but further forelimb development was severely compromised (Fig. 1a,b). Skeletal staining of E14.5 mutants confirmed that hindlimb structures did not develop (Fig. 1c,d).

Table 1.

| Name | Mouse Line | Cross |

|---|---|---|

| Ldb1/2 Control | Ldb1fl/fl;Ldb2-/- | Ldb1fl/fl; Ldb2+/+ X Ldb1+/+;Ldb2-/- |

| Ldb1fl/+;Ldb2+/-;Tcre | Ldb1fl/fl;Ldb2-/- X Ldb1+/+;Ldb2+/+;Tcre | |

| Ldb1/2 double mutant | Ldb1fl/fl;Ldb2-/-;Tcre | Ldb1fl/fl;Ldb2-/- X Ldb1fl/+;Ldb2+/-;Tcre |

| Isl1 Control | Isl1fl/+;Tcre | Isl1fl/fl X Isl1+/+;Tcre |

| Isl1 mutant | Isl1fl/fl;Tcre | Isl1fl/fl X Isl1fl/+;Tcre |

Ldb1fl/fl, Ldb2-/-, Ldb1fl/fl;Ldb2-/-, Tcre, Ldb1fl/+;Ldb2+/-;Tcre, Isl1fl/fl, and Isl1fl/+;Tcre mice appear viable and fertile.

Fig. 1.

Ldb1/2 mutant embryos lack hindlimb formation. Ldb1fl/+;Ldb2+/- control embryo (a) compared to Ldb1fl/fl;Ldb2-/-;Tcre mutant embryo (b) at E13.5. Skeletal structure of a corresponding pair of control Ldb1fl/+;Ldb2+/- (c) and Ldb1fl/fl;Ldb2-/-;Tcre mutant embryos at E14(d). Embryos were stained with alizarin red and alcian blue. FL, forelimb; HL, hindlimb.

Forelimb development is not stopped but merely impaired by the inactivation of the obligatory Ldb co-regulators of Lhx gene activity. In our earlier study on Lhx gene involvement of limb patterning we noticed that that not all cells in the early forelimb bud mesenchyme express T-Cre. As a consequence, part of this mesenchymal tissue escapes Ldb1 ablation (Tzchori et al., 2009). The hindlimb develops about 24 hrs later (Capdevila and Izpisua Belmonte, 2001), At this stage of embryo development, sufficient levels of Cre enzyme may have accumulated in the hindlimb bud mesenchyme to quench most or all Ldb1 activity.

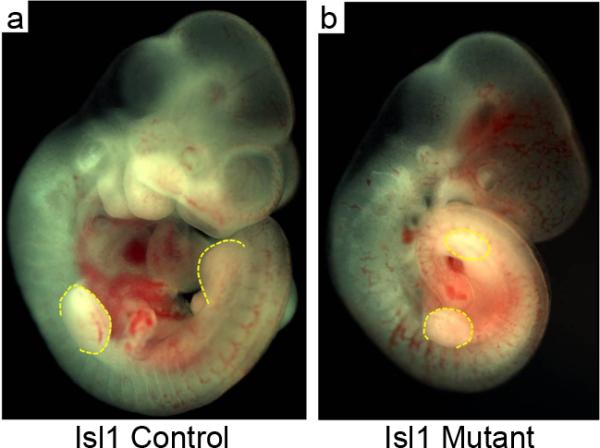

Using a similar approach, we generated mice lacking Isl1 gene activity in the hindlimb bud mesenchyme via T-Cre mediated Isl1 gene inactivation (table 1). Of all the resulting Isl1 mutant embryos (n=>20) less than 30% survived to E10.5, whereas those heterozygous for the Isl1 defect appeared normal. E9-E10.5 embryos were collected. Isl1 mutant embryos were significantly smaller than the controls and lacked hindlimb buds (Fig. 2). Their forelimb bud development was indistinguishable from that of the controls, in keeping with the fact that Isl1 is selectively expressed in the hindlimb bud.

Fig. 2.

Isl1 mutant embryos lack hindlimb formation. Isl1fl/+control embryo (a) compared to Isl1fl/fl;Tcre mutant embryo (b) at E10.5.

In a scenario where Isl1 and the Ldb coregulators are part of a complex regulating early events in hindlimb development, one would expect very similar phenotypes in the respective knockdown mutants provided Isl1 and the Ldb co-regulators work in strict conjunction in the T-Cre targeted cells. However, the Isl1 mutants are much smaller than the Ldb1/2 mutants, and they die earlier. In both cases, knockdown was mediated by T-Cre mediated excision of the Isl1 and the Ldb1 target genes, respectively. Phenotypic discrepancies between the Isl1 and the Ldb1/2 mutants may be best explained by postulating that the floxed Isl1 gene is more accessible than floxed Ldb1 for T-Cre-mediated knockdown. Such differences in Cre access to individual floxed genes have been reported earlier (Vooijs et al., 2001; Birling et al., 2009). In addition or alternatively, differences in the half lives of Isl1 and Ldb1 gene products may have affected the respective mutant phenotypes (Vooijs et al., 2001). Finally, we cannot rule out the possibility that Isl1 has functions that are independent of the co-regulator Ldb.

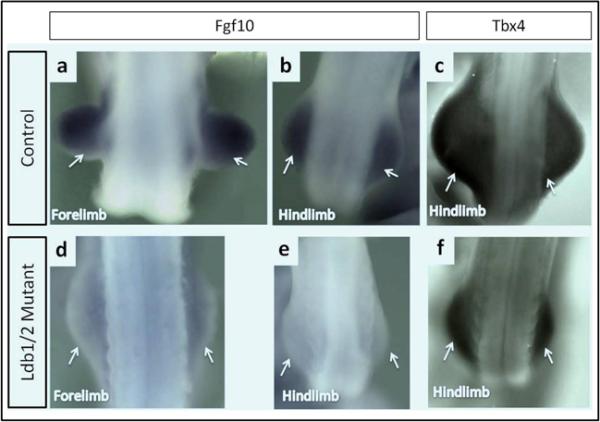

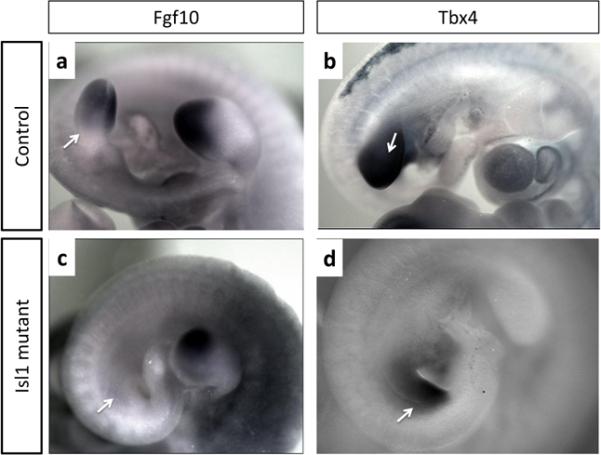

Fgf10 is recognized as a key regulator that is indispensable for limb bud formation (Ohuchi et al., 1997; Min et al., 1998; Sekine et al., 1999). Early hindlimb bud development is curtailed in Ldb1/2, Isl1 and Fgf10 mutants alike. We failed to observe Fgf10 expression in the mesenchyme of the Ldb1/2 and Isl1 mutant hindlimb bud fields (Fig. 3a,d and Fig. 4a,b). This places the activity of the Lhx transcriptional apparatus in the nascent hindlimb bud upstream of Fgf10. In the forelimb region of the Ldb mutants, Fgf10 expression was severely impaired, whereas expression persisted in the Isl1 mutants (Fig. 3b,d). Our data are in full agreement with an extensive study of hindlimb initiation by Kawakami et al. (2011) who showed that Isl1 is required for the activation of the beta catenin pathway upstream of Fgf10.

Fig. 3.

Fgf10 expression is absent in the hindlimb bud of Ldb1/2 mutant embryos. RNA whole mount In situ hybridization. Fgf10 expression in the forelimb and hindlimb buds (a,b) of Ldb1fl/+;Ldb2+/- control compared to the expression in the forelimb and hindlimb buds (d,e) of Ldb1fl/fl;Ldb2-/-;Tcre mutant embryos at E10. Tbx4 expression in the hindlimb buds of Ldb1fl/+;Ldb2+/- control (c) and Ldb1fl/+;Ldb2+/- mutant embryos (f) at E10

Fig. 4.

Fgf10 expression is absent in the hindlimb bud of Isl1 mutant embryos. RNA whole mount In situ hybridization. Fgf10 expression in the hindlimb buds (a) of Isl1fl/+ control (a) compared to that of the Isl1fl/fl;Tcre mutant (b) embryos at E10.5. Tbx4 expression in the hindlimb buds of Isl1fl/+ control (c) and Isl1fl/fl;Tcre mutant embryos (d) at E10. Hindlimb position is indicated by arrows

Isl1 is not expressed in the forelimb bud. Thus, expression of Fgf10 in the forelimb bud is regulated by an as yet unknown Isl1-independent mechanism.

Tbx4 expression in the hindlimb buds, as examined at E10, was noted in both Ldb and Isl1 mutants (Fig. 3c,f and Fig 4c,d). Kawakami et al. (Kawakami et al., 2011) report significant but not complete reduction of Tbx4 expression at E9.5 in the lateral plate mesoderm of Isl1 mutants at E 9.5 and conclude that Isl1 may participate in the regulation of Tbx4 in the hindlimb field. The persistence of Tbx4 expression in Ldb1 and Isl1 mutants that fail to form a hindlimb bud suggests that Tbx4 is not a determining factor of hindlimb bud initiation. Nonetheless, earlier knockout studies provided firm evidence that Tbx4 participates in hindlimb bud development (Naiche and Papaioannou, 2003). The pathways that link Ldb1, Isl1 and Tbx4 during early phases of hindlimb bud development remain to be determined.

We conclude that Isl1 is indispensable for early hindlimb bud formation and that its action in the bud mesenchyme is abrogated either by Isl1 mutation or by removing the obligatory Ldb co-regulators of this Lhx gene. Fgf10 expression in the hind bud mesenchyme is lost if the function of Isl1 or its Ldb co-regulators are curtailed. Both are thus firmly associated with the earliest events in hindlimb development that precede Fgf10 induction in the mesenchymal cells of the nascent limb bud.

Experimental Procedures

Mice strains and genotyping

The Ldb1 conditional mutant mouse has been described previously (Zhao et al., 2007; Tzchori et al., 2009). Primer sequences for genotyping Ldb1 wt alleles (350 bp) and Ldb1 floxed alleles (400 bp) were as follows: Ldb1S 5′-CAG CAA ACG GAG GAA ACG GAA GAT GTC AG-3′ and Ldb1AS 5′-CTT ATG TGA CCA CAGC CAT GCAT GCAT GTG-3′.

Ldb2 knockout mice (unpublished) did not have any discernible phenotype. They were healthy, fertile, and lived a normal lifespan. Primer sequences for genotyping the Ldb2 wt and null alleles were Ldb2 F2 5’- CAG ACT GCT CAT CAC ACA CTT GTT GAT-3’, Ldb2 R2-5’ CTC AAG AAA TCC AAG GGG TGT TAC TTA-3’, SCNEOR 5’-GTC CAG ATC ATC CTG ATC GAC A-3’ and Neo3 5’-GAT CCC CTC AGA AGA ACT CGT-3’, respectively. Primer sequences for genotyping the wt Isl1 allele (452 bp) and the floxed Isl1 allele (519 bp) were Isl1 KC F 5′-GGT GCT TAG CGG TGA TTT CCT C-3′ and Isl1 KC R 5′-GCA CTT TGG GAT GGT AAT TGG AG-3′, respectively. The T-Cre allele was genotyped using the primer sequences T-cre F 5’-CCA TGA GTG AAC GAA CCT GG-3’ and T-Cre R 5’- GGG ACC CAT TTT TCT CTT CC-3’.

Skeletal analysis

Skeletal staining was performed as described previously (Tzchori et al., 2009), with minor modifications. Briefly, E14.5 embryos were dissected in PBS and fixed in 95% ethanol for 1-3 days. Embryos were stained in alcian blue overnight, washed three times in 90% ethanol, incubated in 1% KOH for 2 h, and stained in alizarin red overnight. Embryos were washed in 2% KOH for 3 days or until they were clear, transferred to 20% glycerol in KOH overnight and stored in 50% glycerol in 50% ethanol.

In Situ Hybridization

Whole mount RNA in situ hybridization was performed as described previously (Mukhopadhyay et al., 2003) with minor modifications. The time of proteinase K digestion was 15 minutes for E10.5 embryos and 12 minutes for E9.5 embryos. Exposure to BM purple was overnight at 4°C. When the reaction was complete, the embryos were washed three times in PBT and refixed in 4% PFA for 1 h. Embryos were transferred to 50% then 70% glycerol.

Acknowledgements

The Isl1 conditional mutant mouse was kindly provided by Dr. Lin Gan, University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry. The Fgf10 and Tbx4 probes were generous gifts of Dr. Yingzi Yang, NIH/NHGRI. We thank Dr. Karl Pfeifer and Dr. Sohyun Ahn for helpful discussions. This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

References

- Agarwal P, Wylie JN, Galceran J, Arkhitko O, Li C, Deng C, Grosschedl R, Bruneau BG. Tbx5 is essential for forelimb bud initiation following patterning of the limb field in the mouse embryo. Development. 2003;130:623–633. doi: 10.1242/dev.00191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birling MC, Gofflot F, Warot X. Site-specific recombinases for manipulation of the mouse genome. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;561:245–263. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-019-9_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke AC, Nelson CE, Morgan BA, Tabin C. Hox genes and the evolution of vertebrate axial morphology. Development. 1995;121:333–346. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.2.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capdevila J, Izpisua Belmonte JC. Patterning mechanisms controlling vertebrate limb development. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2001;17:87–132. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.17.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman DL, Garvey N, Hancock S, Alexiou M, Agulnik SI, Gibson-Brown JJ, Cebra-Thomas J, Bollag RJ, Silver LM, Papaioannou VE. Expression of the T-box family genes, Tbx1-Tbx5, during early mouse development. Dev Dyn. 1996;206:379–390. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199608)206:4<379::AID-AJA4>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen B, McGuffin ME, Pfeifle C, Segal D, Cohen SM. apterous, a gene required for imaginal disc development in Drosophila encodes a member of the LIM family of developmental regulatory proteins. Genes Dev. 1992;6:715–729. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.5.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crossley PH, Minowada G, MacArthur CA, Martin GR. Roles for FGF8 in the induction, initiation, and maintenance of chick limb development. Cell. 1996;84:127–136. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80999-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Benjumea FJ, Cohen SM. Interaction between dorsal and ventral cells in the imaginal disc directs wing development in Drosophila. Cell. 1993;75:741–752. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90494-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson-Brown JJ, Agulnik SI, Chapman DL, Alexiou M, Garvey N, Silver LM, Papaioannou VE. Evidence of a role for T-box genes in the evolution of limb morphogenesis and the specification of forelimb/hindlimb identity. Mech Dev. 1996;56:93–101. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(96)00514-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawakami Y, Marti M, Kawakami H, Itou J, Quach T, Johnson A, Sahara S, O'Leary DD, Nakagawa Y, Lewandoski M, Pfaff S, Evans SM, Izpisua Belmonte JC. Islet1-mediated activation of the {beta}-catenin pathway is necessary for hindlimb initiation in mice. Development. 2011;138:4465–4473. doi: 10.1242/dev.065359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewandoski M, Sun X, Martin GR. Fgf8 signalling from the AER is essential for normal limb development. Nat Genet. 2000;26:460–463. doi: 10.1038/82609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min H, Danilenko DM, Scully SA, Bolon B, Ring BD, Tarpley JE, DeRose M, Simonet WS. Fgf-10 is required for both limb and lung development and exhibits striking functional similarity to Drosophila branchless. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3156–3161. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.20.3156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon AM, Capecchi MR. Fgf8 is required for outgrowth and patterning of the limbs. Nat Genet. 2000;26:455–459. doi: 10.1038/82601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay M, Teufel A, Yamashita T, Agulnick AD, Chen L, Downs KM, Schindler A, Grinberg A, Huang SP, Dorward D, Westphal H. Functional ablation of the mouse Ldb1 gene results in severe patterning defects during gastrulation. Development. 2003;130:495–505. doi: 10.1242/dev.00225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naiche LA, Papaioannou VE. Loss of Tbx4 blocks hindlimb development and affects vascularization and fusion of the allantois. Development. 2003;130:2681–2693. doi: 10.1242/dev.00504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng M, Diaz-Benjumea FJ, Vincent JP, Wu J, Cohen SM. Specification of the wing by localized expression of wingless protein. Nature. 1996;381:316–318. doi: 10.1038/381316a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohuchi H, Nakagawa T, Yamamoto A, Araga A, Ohata T, Ishimaru Y, Yoshioka H, Kuwana T, Nohno T, Yamasaki M, Itoh N, Noji S. The mesenchymal factor, FGF10, initiates and maintains the outgrowth of the chick limb bud through interaction with FGF8, an apical ectodermal factor. Development. 1997;124:2235–2244. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.11.2235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perantoni AO, Timofeeva O, Naillat F, Richman C, Pajni-Underwood S, Wilson C, Vainio S, Dove LF, Lewandoski M. Inactivation of FGF8 in early mesoderm reveals an essential role in kidney development. Development. 2005;132:3859–3871. doi: 10.1242/dev.01945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekine K, Ohuchi H, Fujiwara M, Yamasaki M, Yoshizawa T, Sato T, Yagishita N, Matsui D, Koga Y, Itoh N, Kato S. Fgf10 is essential for limb and lung formation. Nat Genet. 1999;21:138–141. doi: 10.1038/5096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X, Mariani FV, Martin GR. Functions of FGF signalling from the apical ectodermal ridge in limb development. Nature. 2002;418:501–508. doi: 10.1038/nature00902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Liang X, Najafi N, Cass M, Lin L, Cai CL, Chen J, Evans SM. Islet 1 is expressed in distinct cardiovascular lineages, including pacemaker and coronary vascular cells. Dev Biol. 2007;304:286–296. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.12.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzchori I, Day TF, Carolan PJ, Zhao Y, Wassif CA, Li L, Lewandoski M, Gorivodsky M, Love PE, Porter FD, Westphal H, Yang Y. LIM homeobox transcription factors integrate signaling events that control three-dimensional limb patterning and growth. Development. 2009;136:1375–1385. doi: 10.1242/dev.026476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verheyden JM, Lewandoski M, Deng C, Harfe BD, Sun X. Conditional inactivation of Fgfr1 in mouse defines its role in limb bud establishment, outgrowth and digit patterning. Development. 2005;132:4235–4245. doi: 10.1242/dev.02001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel A, Rodriguez C, Izpisua-Belmonte JC. Involvement of FGF-8 in initiation, outgrowth and patterning of the vertebrate limb. Development. 1996;122:1737–1750. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.6.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vooijs M, Jonkers J, Berns A. A highly efficient ligand-regulated Cre recombinase mouse line shows that LoxP recombination is position dependent. EMBO Rep. 2001;2:292–297. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeller R, Lopez-Rios J, Zuniga A. Vertebrate limb bud development: moving towards integrative analysis of organogenesis. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:845–858. doi: 10.1038/nrg2681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Kwan KM, Mailloux CM, Lee WK, Grinberg A, Wurst W, Behringer RR, Westphal H. LIM-homeodomain proteins Lhx1 and Lhx5, and their cofactor Ldb1, control Purkinje cell differentiation in the developing cerebellum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:13182–13186. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705464104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]