Abstract

The aim of the present work was to investigate the occurrence of the cell cycle during germination as related to thermodormancy in barley (Hordeum vulgare L., cv. Pewter) grains in relation with abscisic acid (ABA) by: (i) flow cytometry to determine the progression of the cell cycle; and (ii) reverse transcription-PCR to characterize the expression of some important genes involved in cell-cycle regulation. In dry embryos, cells are mostly (82%) arrested in G1 phase of the cell cycle, the remaining cells being in the G2 (17%) or S phase (0.9%). Germination at 20 °C was associated with an increase in the nuclei population in G2 and S (up to 32.5–44.5 and 9.2–11.3%, respectively, after 18–24h). At 30 °C, partial reactivation of the cell cycle occurred in embryos of dormant grains that did not germinate. Incubation with 50mM hydroxyurea suggests that thermodormancy resulted in a blocking of the nuclei in the S phase. In dry dormant grains, transcripts of CDKA1, CYCA3, KRP4, and WEE1 were present, while those of CDKB1, CDKD1, CYCB1, and CYCD4 were not detected. Incubation at 30 °C resulted in a strong reduction of CDKB1, CYCB1, and CYCD4 expression and overexpression of CDK1 and KRP4. ABA had a similar effect as incubation at 30 °C on the expression of CDKB1, CYCB1, and CYCD4, but did not increase that of CDK1 and KRP4. Patterns of gene expression are discussed with regard to thermodormancy expression and ABA.

Key words: Abscisic acid, barley, cell cycle, cyclin, cyclin-dependent kinase, dormancy, germination, Hordeum vulgare L., KIP related protein

Introduction

The germination of seeds is essential to the life cycle of plants. It is initiated upon uptake of water by the dry seeds and is considered complete upon initiation of elongation of the embryonic root (Bewley and Black, 1994), this process not requiring mitotic activity (Gornik et al., 1997; Gendreau et al., 2008). The involvement of cell-cycle activation in germination is debatable. A current hypothesis is that cell-cycle activation, especially progression into the G1 phase, is required for germination (Vázquez-Ramos and Sanchez, 2003). Seed dormancy is a trait that is imposed during the latter stages of seed development and prevents germination in an apparently suitable environment (Bewley, 1997). In cereals originating from temperate climates, such as barley, oat, and wheat, primary dormancy of mature grains is temperature dependent and is generally expressed above 15–20 °C (Lenoir et al., 1983; Simpson, 1990; Corbineau and Côme, 1996; Benech-Arnold, 2004). There is little evidence for a role on the cell cycle in maintenance of the dormant state. However, nuclei of imbibed dormant seeds of tomato have been reported to remain in a G1-like state until dormancy is released (De Castro et al., 2001).

Cell-cycle progression is controlled by different protein complexes associating cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) and a catalytic subunit, cyclin (Inzé and De Veylder, 2006; Berckmans and De Veylder, 2009). The association of a CDK with a specific cyclin partner determines the activity of the cyclin–CDK complex (Pines, 1995; Dewitte and Murray, 2003). Five types of CDK have been identified in plants, from CDKA to CDKE (Joubès et al., 2000). The CDKA group, characterized by a PSTAIRE motif, plays a role at both the G1-to-S and G2-to-M transition points. The CDKB class, characterized by a PPTALRE motif, is required to progress through mitosis (Inzé and De Veylder, 2006). In plants, cyclins have been classified into five major groups: A, B, C, D, and H (Vandepoele et al., 2002). The A-type cyclins accumulate during S–M phases and the B-type cyclins accumulate during G2–M phases and regulate entry into the M phase. The D-type cyclins are expressed earlier in the cell cycle and control the progression from the early G1 phase to S phase in response to external growth signals, some D-type cyclins may also act in G2/M (Meijer and Murray, 2000; Koroleva et al., 2004; Planchais et al., 2004). Active cyclin–CDK complexes can be inhibited by another regulating class of protein: cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors, also known as Kip-related protein (KRP) (Oakenfull et al., 2002). In Arabidopsis, seven genes have been identified as KRPs (De Veylder et al., 2001). All KRPs, except KRP5, interact with CDKA1 and none interact with CDKB1, these interactions inducing a possible inhibition of cyclin–CDK complex activity. Futhermore, KRPs regulate both DNA synthesis and mitosis by binding and inhibiting A-type CDKs through their conserved CDK-binding domain (Oakenfull et al., 2002). To complete the regulation of cell-cycle protein, it is important to notice that proteolysis of cell-cycle proteins, especially cyclins, is a common mechanism leading to an irreversible moving forward of the cycle (Genschik et al., 1998; De Veylder et al., 2007).

In higher plants, the phytohormone abscisic acid (ABA) regulates many processes of plant development, including synthesis of seed storage proteins, promotion of seed desiccation tolerance, and dormancy (Bewley, 1997; Feurtado and Kermode, 2007). ABA is also known to inhibit cell-cycle processes in G1 (Liu et al., 1994; Swiatek et al., 2002; Sánchez et al., 2005), since it can induce genes such as KRP (Wang et al., 1998). Thus, KRP genes may be good candidates to block cell-cycle progression via ABA in dormant seeds.

The objectives of the present study were: (i) to investigate whether cell-cycle progression in dormant barley grains is related to temperature; (ii) to determine the effects of high temperature, which inhibits the germination, on the expression of the main genes involved in cell-cycle activity; and (iii) to study whether ABA interferes with cell-cycle progression as related to dormancy expression, and if so at which cell-cycle step. Experiments were performed with mature dormant grains at 20°C, a temperature at which germination can occur, and at 30°C, a temperature at which germination is impossible (Corbineau and Côme, 1996; Benech-Arnold et al., 2006). It is shown here that expression of dormancy at 30°C is associated with a blocking of the nuclei in the S phase that is related to a strong reduction in CDKB1, CYCB1, and CYCD4 transcript accumulation, and an overexpression of CDKD1 and KRP4. Application of exogenous ABA at 20 °C induced a similar effect to incubation at 30 °C but did not induce expression of CDKD1 and KRP4.

Materials and methods

Plant material

Barley (Hordeum vulgare L., cv. Pewter) seeds were harvested in July 2004 at the end of the maturation drying phase, i.e. when their water content reached 0.10–0.12g H2O (g dry weight)–1 (DW), and were provided by the ‘Coopérative de Toury’ (Eure et Loir, France). Seeds were stored at –18 °C in order to maintain their dormancy (Corbineau and Côme, 1996) until experiments started.

Germination assays

Germination assays were performed at 20 or 30 °C in darkness, in three replicates of 50 grains placed in 9-cm diameter Petri dishes on a layer of cotton wool imbibed with deionized water. A grain was regarded as germinated when the radicle had protruded through the seed-covering structures. Germination counts were conducted regularly for 7 d. The results presented correspond to the mean ± SD of the germination percentages obtained in three replicates.

Experiments with 1mM ABA or 50mM hydroxyurea, an inhibitor of the S phase (Planchais et al., 2000) were done by incubating seeds with these compounds from the beginning of imbibition.

Radicle elongation measurement

Radicle lengths of seedlings were measured for seeds incubated at 20 °C with water, 1mM ABA or 50mM hydroxyurea after 24, 48, and 72h. The results correspond to the mean ± SD of 30 measurements.

Flow cytometry

Amounts of nuclear DNA were quantified using radicles of embryos isolated from grains incubated for various times at 20 °C and 30 °C with water or at 20 °C with 1mM ABA. Samples of 15 radicles including coleorhiza were chopped on ice with a razor blade in 400 µl nuclear isolation buffer (20mM MOPS, 30mM Na citrate, 45mM MgCl2, 1% Triton X-100, w/v; adapted from Galbraith et al., 1983). The suspension was sieved through a 48 µm nylon mesh. After 15min digestion with RNase (1 µg in 10 µl) at room temperature, the samples were stained with propidium iodide (1mg ml–1) to allow measurement of the amount of nuclear DNA by fluorescence. DNA analyses were performed using an EPICS XL-MCL flow cytometer (Beckman-Coulter, Miami, FL, USA) equipped with an argon ion laser at 488nm and fluorescence was detected over a range 605–635nm. The amount of DNA is proportional to the fluorescent signal and is expressed as an arbitrary C value, in which the 1C value represents the amount of DNA of the unreplicated haploid chromosome complement. Three experiments were performed independently and the results presented correspond to a representative single experiment. The frequency of 2C, 4C, and S-phase nuclei was calculated as [2C nuclei/(2C nuclei + 4C nuclei + S-phase nuclei)] × 100, [4C nuclei/(2C nuclei + 4C nuclei + S-phase nuclei)] × 100, and [S-phase nuclei/(2C nuclei + 4C nuclei + S-phase nuclei)] × 100, respectively. The average variation between two measurements of a population of nuclei was ~3%. The different nuclei populations were measured for 10,000 nuclei.

RNA extraction

Embryos were isolated from the endosperm using a sharp scalpel blade, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and then stored at –80 °C. For each extract, 30 embryos were ground in liquid N2, and total RNA was extracted by a hot phenol procedure according to Verwoerd et al. (1989).

EST database search

In order to analyse cell-cycle transcription activity, the expression of related genes as markers of cell-cycle phase was studied. The TIGR barley expressed sequence tag (EST) databank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/Blast.cgi?PAGE_TYPE=BlastSearch&PROG_DEF=blastn&BLAST_PROG_DEF=megaBlast&BLAST_SPEC=Plants_EST) was screened using specific protein motifs for each class to identify barley genes. To complete and confirm the databank annotation, specific protein motifs were identified using the translation software from infobiogene (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/wrpsb.cgi). A class could be attributed for each gene with specific motifs, i.e. for CDKDA (CDKA1), CDKB (CDKB1), CDKD (CDKD1), CYCA (CYCA3), CYCB (CYCB1), and CYCD (CYCD4) (Vandepoele et al., 2002), and KRP (KRP4) and WEE (WEE1) (Sorrell et al., 2002). Specific primers were then designed using the software Primer3 for each EST (Supplementary Table S1) to perform reverse-transcription (RT) PCR. As an internal standard, a fragment of the barley actin gene (GI24496451) was used. Each expression profile presented was repeated at least three times in three independent experiments.

Reverse-transcription PCR

Total RNA (4 µg) was treated with DNase I (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) and then was reverse transcribed with Revertaid H minus M-MuLVRT (Fermentas, Vilnius, Lithuania). All oligonucleotides were obtained from Eurogentec (Seraing, Belgium). For semiquantitative PCR, amplifications were performed using a Mastercycler (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) with 1U Taq polymerase (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA, USA), 0.4mM dNTP, and 0.8 µM each primer in a 25 µl reaction volume. The thermal cycling program was initiation at 94 °C for 2min, 25 cycles for CDK and actin genes or 30 cycles for cyclin genes at 94 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s, and termination at 72 °C for 5min. Amplification products were detected on an agarose gel with ethidium bromide and quantified with Quantity One software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The actin level in each lane was used as an internal standard. the results presented correspond to representative profiles of gene expression obtained in three independent experiments.

Results

Germination of dormant grains at 20 and 30 °C

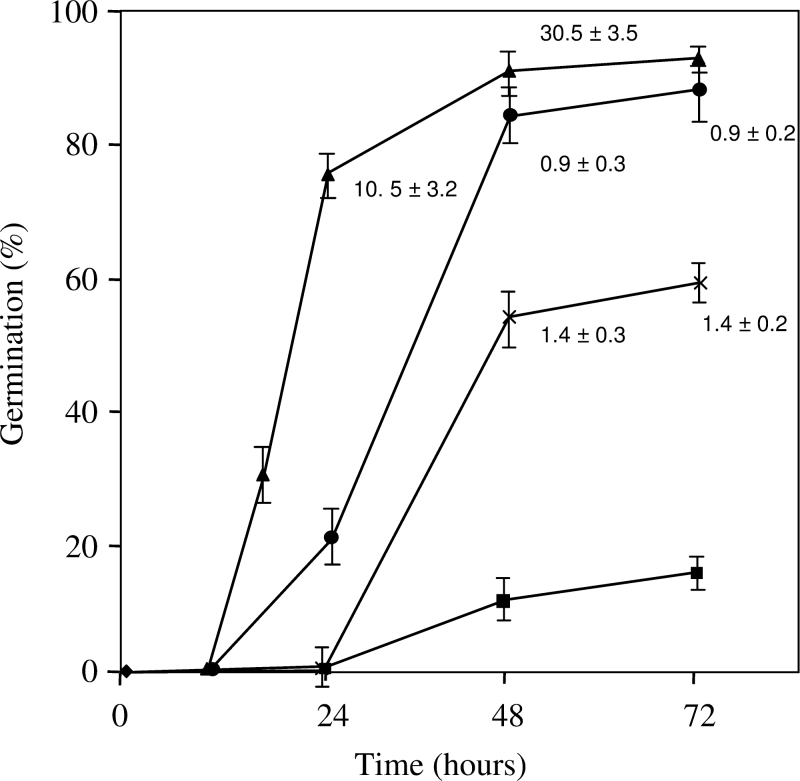

At harvest, seeds were considered dormant since only 10% of the seed population germinated at 30 °C although almost all (90%) were able to germinate within 48h at 20 °C (Fig. 1). Incubation of the grains with 1mM ABA resulted in an inhibition of the germination rate: 58% of grains germinated within 72h against 90% with water. The time to obtain 50% germination (T50) was about 20 and 48h with water and ABA, respectively (Fig. 1). Hydroxyurea (50mM) only slightly inhibited seed germination at 20 °C; T50 was 34h and more than 80% of the grains germinated within 48h.

Fig. 1.

Time course of germination of dormant grains at 20 °C with water (▴), with 1mM ABA (×) or 50mM hydroxyurea (○) and at 30 °C with water (▪). Values are mean ± SD of three replicates. Numbers on the curves correspond to radicle length in mm (mean ± SD of 30 measurements).

The mean length of radicles of seeds incubated with water was 30.5mm after 48h at 20 °C, and radicle length did not exceed 0.9 and 1.4mm with hydroxyurea and ABA, respectively (Fig. 1).

Cell-cycle activity during germination

In dry grains, approximately 82 and 17% of the nuclei of the embryonic axes gave 2C and 4C signals, respectively, indicating that the majority of cells were arrested at the G1 phase of the cell cycle (Table 1). Only 0.9% of the nuclei gave an intermediate signal and were considered as being in the S phase (Table 1).

Table 1.

Percentage of nuclei giving 2C, 4C, and S-phase signal of cells of embryonic radicle tips isolated from dry seeds and seeds incubated for various durations at 20 °C with water or with 1mM ABA, or at 30 °C with water with or without 50mM hydroxyurea

Values are mean ± SD of three measurements carried out on 10000 nuclei. The frequency of 2C, 4C, and S-phase nuclei was calculated as [2C nuclei/(2C nuclei + 4C nuclei + S-phase nuclei)] × 100, [4C nuclei/(2C nuclei + 4C nuclei + S-phase nuclei)] × 100, and [S-phase nuclei/(2C nuclei + 4C nuclei + S-phase nuclei)] × 100, respectively. The 2C* population corresponds to nuclei of cells entering S phase but blocked from further DNA synthesis by the presence of 50mM hydroxyurea (Hur). It was integrated to the total amount of nuclei for the hydroxyurea treatments.

| Imbibition time (h) | Treatment | Nuclei (%) in: | 4C/2C | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2C | 2C* | 4C | S-phase | |||

| 0 | Dry seed | 82.2±3.1 | 17.1±1.6 | 0.9±1.3 | 0.20 | |

| 18 | Water (20 °C) | 58.1±2.6 | 32.5±1.3 | 9.2±1.4 | 0.56 | |

| 24 | Water (20 °C) | 44.1±2.2 | 44.5±1.8 | 11.3±1.6 | 1.01 | |

| Water + Hur (20 °C) | 46.2±2.3 | 44.1±1.2 | 8.5±1.5 | 2.3±1.5 | 0.09 | |

| ABA (20 °C) | 69.6±1.5 | 26.2±1.9 | 4.3±1.3 | 0.38 | ||

| ABA + Hur (20 °C) | 68.1±2.2 | – | 27.5±1.2 | 5±1.4 | 0.40 | |

| Water (30 °C) | 59.9±2.5 | 30.9±1.5 | 8.8±2.5 | 0.52 | ||

| Water + Hur (30 °C) | 49.1±1.9 | 12.6±1.1 | 37.5±1.8 | 2.3±1.1 | 0.72 | |

| 48 | Water (20 °C) | 34.2±1.9 | 56.8±1.5 | 9.5±1.9 | 1.66 | |

| ABA (20 °C) | 66.5±1.8 | 28.6±2.5 | 4.8±0.9 | 0.43 | ||

| Water (30 °C) | 59.4±1.9 | 29.8±1.8 | 10.6±2.5 | 0.50 | ||

| 72 | Water (20 °C) | – | – | – | – | |

| ABA (20 °C) | 65.3±1.6 | 29.2±1.6 | 5.7±1.0 | 0.44 | ||

| Water (30 °C) | 60.4±2.0 | 30.0±1.8 | 9.6±2.2 | 0.50 | ||

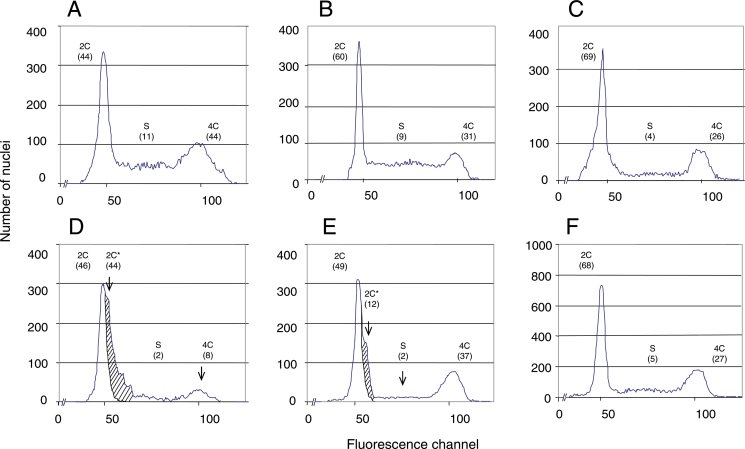

At 20 °C, germination was associated with an increase in the 4C nuclei population up to 32.5% after 18h, i.e. when 30% of the grains germinated, and 56.8% after 48h, i.e. when germination rate was maximal (90%) (Table 1). The 4C/2C ratio increased from 0.20 in dry seeds up to 0.56 after 18h of imbibition at 20 °C and reached 1.01 and 1.66 after 24 and 48h, respectively. The percentage of nuclei in S phase remained between 9.2 and 11.3 (Table 1). After 24h, 44.1, 44.5, and 11.3% of of radicle-tip nuclei were in the G1, G2, or S phase of the cell cycle (Table 1, Fig. 2A). Incubation of grains with 50mM hydroxyurea, an inhibitor of the S phase, did not suppress radicle protrusion (cf. Fig. 1), but resulted in a blocking of the cell cycle (Fig. 2D); a second shoulder in the 2C peak of nuclei was then observed, representing cells re-entering the cell cycle but blocked in the S phase (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

Flow cytometric analysis of nuclei from embryo radicles isolated from germinating grains: (A–C) after 24h with water at 20 °C (A) and 30 °C (B) or with 1mM ABA at 20 °C (C); (D–F) as for A–C but also with 50mM hydroxyurea. Numbers in parentheses indicate percentage of nuclei in 2C, 2C*, S, and 4C cell-cycle phases. Hatched area corresponds to nuclei entering S phase but blocked (2C*) from further DNA synthesis by the presence of hydroxyurea. The average variation between two independent measurements of a population of nuclei is 3% maximum. Measurements were carried out on 10,000 nuclei.

At 30 °C, there was a reactivation of the cell cycle; 30.9% of the nuclei population were in G2 phase against 17.1% for radicle tips of embryos from dry grains (Table 1). From 24 to 72h of imbibition, nuclei in the G1, G2, or S phase represented 59.4–60.4, 29.8–30.9, and 8.8–10.6% of the population, respectively (Table 1, Fig. 2B). The 4C/2C ratio remained at 0.50. When seeds were incubated with hydroxyurea (Fig. 2E), some nuclei (12%) re-entered the cell cycle but were blocked in G1 phase, suggesting that, in the dormant state, nuclei were blocked in the S phase.

ABA (1mM) inhibited germination (Fig. 1) and cell-cycle reactivation as compared with control grains incubated at 20 °C with water (Table 1). The percentage of nuclei with the 4C signal was between 26.2% (after 24h) (Fig. 2C) and 29.2% (after 72h), values that were close to those observed for grains incubated at 30 °C (Table 1), a temperature at which the seeds could not germinate (cf. Fig. 1). However, the 4C/2C ratio was lower (0.38–0.44) than that for dormant seeds incubated with water at 30 °C (0.50–0.52) (Table 1). Nuclei with an intermediate DNA signal, i.e. in an apparent S phase, corresponded to only 4–5% of the population, while they represented about 10% of the nuclei population when incubated with water either at 20 or 30 °C (Fig. 2C, Table 1). Application of hydroxyurea did not result in a shoulder in the 2C peak (Fig. 2F).

Expression of CDK, CYC, KRP, and WEE

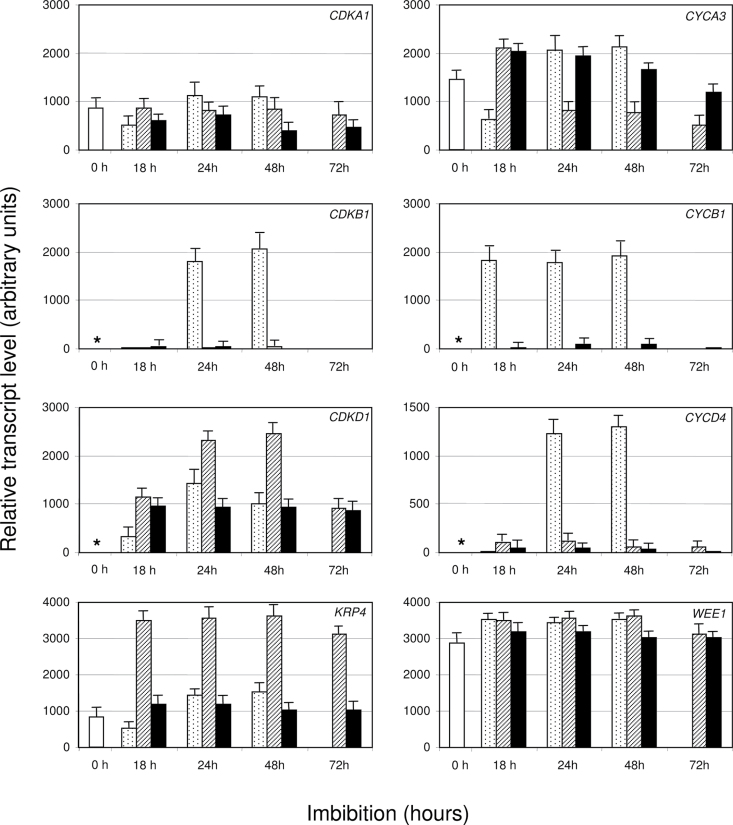

Changes in transcript abundance of CDK (CDKA1, CDKB1, and CDKD1), cyclins (CYCA3, CYCB1, and CYCD4) and regulatory genes such as KRP4 and WEE1 were analysed by RT-PCR in embryos during incubation of seeds at 20 and 30 °C with water or at 20 °C with 1mM ABA. The results are presented in Fig. 3, and Supplementary Fig. S1 shows the expression profiles. Transcripts of some genes (CDKA1, CYCA3, KRP4, and WEE1) were present in dry seeds, while those of CDKB1, CDKD1, CYCB1, and CYCD4 were not detected. CDKA1, KRP4, and WEE1 expression did not change significantly during seed imbibition/germination at 20 °C. In contrast, CDKB1, CDKD1, CYCA3, CYCB1, and CYCD4 transcripts accumulated during germination, with CYCB1 expression reaching a maximum at 18h, while the expression of the other genes was maximal at 24h, i.e. when about 80% of the grain population germinated (cf. Fig. 1).

Fig. 3.

Transcript abundance of the main genes involved in cell-cycle activity in embryos of grains incubated at 20 and 30 °C with water, or at 20 °C with 1mM ABA. Data from RT-PCR (mean ± SD of three replicates) are given in arbitrary units. Dry seeds (white), seeds incubated at 20 °C with water (light grey), 30 °C with water (dark grey), or at 20 °C on 1mM ABA (black). *, no detectable signal.

Incubation of the grains at 30 °C resulted in an almost complete suppression of CDKB1, CYCB1, and CYCD4 expression (Fig. 3) and in an overexpression of CDKD1 and KRP4. Expression of CDKA1 and WEE1 was not significantly affected at 30 °C as compared to 20 °C, when that of CYCA3 was higher at 18h and then reduced from 24h.

Application of exogenous 1mM ABA at 20 °C, similarly to incubation at 30 °C, resulted in a suppression of the expression of CDKB1, CYCB1, and CYCD4 (Fig. 3). However, ABA did not increase the expression of CDKD1 and KRP4. With the exception of 18h incubation, expression of CDKA1, CDKD1, CYCA3, KRP4, and WEE1 was close to that measured in embryos of control grains incubated at 20 °C with water.

Discussion

As previously shown in non-dormant barley grains (Gendreau et al., 2008) and other species (Bino et al., 1993; Lanteri et al., 1994; Özbingöl et al., 1999; Sánchez et al., 2005), the majority of radicle-tip nuclei of dry dormant barley grains arrested in G1 phase of the cell cycle, i.e. with a 2C DNA level, the remaining cells being in G2 or S phase. In non-dormant grains, 8% of the nuclei population arrested in the cell cycle with 4C DNA levels (Gendreau et al., 2008) while 4C signals were observed in 17% of the nuclei population in dormant grains at harvest (Table 1). This decrease in the G2 nuclei population during after-ripening might result from a progressive dehydration of the grain during dry storage, as observed in sugar beet seeds after drying (Sliwinska, 2003).

Seed dormancy is defined as an inability to germinate in apparently favourable conditions (Bewley and Black, 1994; Bewley, 1997). In barley, it corresponds to a difficult germination at temperatures higher than 20 °C (Corbineau and Côme, 1996; Benech-Arnold, 2004). At 20 °C, a temperature at which dormancy was not expressed in the current seed batch, the time to obtain 50% germination was about 20h (Fig. 1), and cell-cycle activity was initiated in radicle-tip nuclei after 18h of imbibition, i.e. before the radicle elongation of all seeds (Table 1). The induction of the cell cycle during imbibition varies among species; the G2 population reaches 56% at 14h, when radicle protrusion occurs, in non-dormant barley grains (Gendreau et al., 2008), 35% at 15h in maize (Sánchez et al., 2005), and 30–39% in sugar beet (Sliwinska, 2000). On the other hand, application of 50mM hydroxyurea, which resulted in a blocking of the cell cycle (Fig. 2D and Table 1), did not prevent germination but inhibited radicle growth (Fig. 1), suggesting that cell-cycle initiation may not be totally required for the early phases of germination.

At 30 °C, a temperature at which dormant grains cannot germinate (Fig. 1), the dynamic of the cell cycle was different than that at 20 °C (Figs 2A and 2B and Table 1). A partial activation occurred, 30% of the nuclei moving from G1 to G2 at 24h, but the proportion of 4C nuclei remained at this level until 72h, versus 44.5–56.8% at 20 °C. The results obtained with hydroxyurea suggest that, at 30 °C, the cell cycle is not being completed. The G2 population remained stable (about 37.5%) even after blocking the S phase (Fig. 2E and Table 1), when it was lowered to 8.5% at 20 °C (Fig. 2D and Table 1), probably because nuclei moved to the M and G1 phases. It can be concluded that, in non-germinated dormant barley seeds at 30 °C, the nuclei of the radicle tips are blocked in the G2/M transition and in the S phase.

Similarly to numerous species (Bewley, 1997; Nambara and Marion-Poll, 2003; Nambara et al., 2010), barley seed dormancy and germination are mainly regulated by ABA (Benech-Arnold et al., 2006; Millar et al., 2006). The inability of dormant barley grains to germinate at 30 °C is associated with a maintenance of a high concentration of ABA (Benech-Arnold et al., 2006; Gubler et al., 2008) and higher embryo sensitivity to ABA (Corbineau and Côme, 2000; Benech-Arnold et al., 1999, 2006). In the current study, at 20 °C, exogenous ABA (1mM) inhibited germination (Fig. 1) and resulted in an almost 2-fold reduction of the 4C nuclei population at 24 and 48h of imbibition (Table 1). The hydroxyurea treatment revealed that ABA, similarly to incubation at 30 °C, resulted in a blocking of the G2/M and G1/S transitions.

Similarly to non-dormant seeds (Gendreau et al., 2008), major changes in the transcript levels of CDK and CYC occurred in the embryo during incubation at 20 °C (Fig. 3), a temperature at which dormant seeds germinated (Fig. 1). In contrast, at 30 °C and at 20 °C with ABA, expression of CDKA1 and CDKD1 suggested that cell-cycle progression was possible, but the lack of expression of CDKB1 might explain the arrest in G1/S transition observed (Menges et al., 2005).

Absence of germination of dormant grains at 30 °C and at 20 °C with ABA is associated with low expression of CYCB1 and CYCD4 (Fig. 3), which might be a cause of the arrest in the G2/M and G1/S transition of the cell cycle, respectively (Menges et al., 2005). CYCB1 was not also induced in non-dormant barley seeds incubated with low water content, which did not allow germination, while expression of CYCD4 remained high in correlation with an increase in the 4C population (Gendreau et al., 2008). Since cyclins are strongly regulated at the transcriptional level (Barrôco et al., 2005), the disappearance of CYCB1 might be a good indication of the regulation of the cell cycle at the G2/M transition when no germination occurs independently of the dormancy phenomenon. In contrast, the reduced expression of CYCD4 is related to dormancy per se and not to the absence of germination.

KRP negatively regulates the cyclin–CDK complex at the G1/S phase transition by interfering with formation of the complex (Oakenfull et al., 2002; Cho et al., 2009). In the barley databank, one KRP was found with a clear protein motif as in KRP4 and KRP6 according to the KRP classification of De Veylder et al. (1999). The current results indicate that KRP4 is expressed even when the cell cycle is turning normally at 20 °C and that KRP4 is upregulated at 30 °C. However, its expression was not increased with exogenous ABA at 20 °C, although KRPs have been shown to be induced by ABA (Wang et al., 1998; Ruggiero et al., 2004). Nevertheless, KRP4 overexpression at 30 °C could be considered a good candidate to explain cell-cycle progression in embryos of dormant seeds incubated at high temperatures. WEE1 expression, involved in the G2/M transition, did not change as a function of incubation time either at 20 or 30 °C or even at 20 °C with ABA (Fig. 3); thus, if this gene is involved, it is probably not through its transcriptional expression.

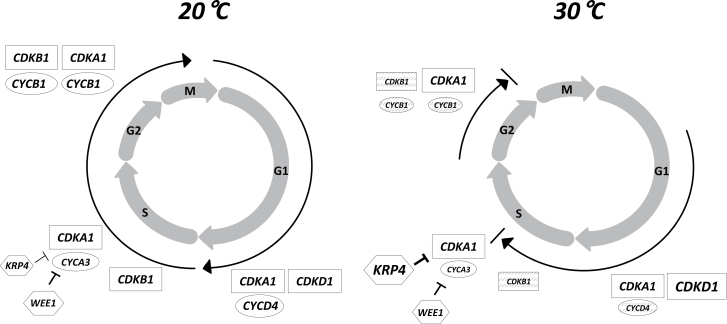

Overall, the results reported here shed new light on the regulation of the cell cycle during incubation of dormant barley seeds as related to temperature. Fig. 4 gives a diagram depicting cell-cycle progression in dormant barley seeds incubated at 20 and 30 °C as related to the expression of CDK, CYC, and KRP genes. When germination can occur, for example at 20 °C, the cell cycle is initiated early, before radicle elongation, as previously shown in non-dormant barley grains (Gendreau et al., 2008) and in Arabidopsis thaliana (Barrôco et al., 2005; Inzé and De Veylder, 2006). The inability of dormant grains incubated at 30 °C to germinate is a blocking of the G2/M transition, with a downregulation of the expression of CDKB1 and CYC A3, B1, and D4 and an upregulation of CDKD1 and KRP4. Comparison between the expression profiles of the main genes involved in cell-cycle activity in non-germinated dormant barley grains incubated at 30 °C (Fig. 3) and in non-dormant grains partially hydrated at 30 °C (Gendreau et al., 2008) allows the current study to propose that the blockage in the G2/M transition and the S phase in embryos of dormant seeds incubated at 30 °C involves a specific regulation through CYCD4 and KRP4. Application of 1mM ABA inhibited germination at 20 °C (Fig. 1) but surprisingly did not simulate the effect of incubation at 30 °C at the level of gene expression (Fig. 3). Therefore, it is suggested that cell-cycle regulation during incubation of dormant seeds is only partially by the metabolism of ABA.

Fig. 4.

The regulation of cell-cycle progression in dormant barley grains incubated at 20 and 30 °C. At 20 °C, temperature at which the grains can germinate, the cell cycle can progress through expression of CDK (CDKA1, CDKB1, CDKD1) and CYC (CYCA3, CYCB1, CYCD4); expression of KRP4 is low. At 30 °C, the cell cycle is blocked in the S phase and at the G2/M transition which is related to a strong reduction in CYCD4, CDKB1, CYCA3, and CYCB1 transcript accumulation and an overexpression of KRP4. Very low expression is specified in grey. ABA has the same effects as 30 °C on all genes, except on the expression of KRP4, which is not enhanced.

Supplementary material

Supplementary data are available at JXB online.

Supplementary Table S1. Oligonucleotide sequences used for reverse transcription PCR.

Supplementary Fig. S1. Expression profiles of the main genes involved in cell-cycle activity in embryos of grains incubated at 20 °C and 30 °C with water or at 20 °C with 1mM ABA.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0/uk/) which permits unrestricted noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

© 2012 The Authors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Spencer Brown (Plateforme de Cytologie, Institute des Sciences Vegetales, CNRS, Gif sur Yvette, France) for his skill in flow cytometry.

Footnotes

This paper is available online free of all access charges (see http://jxb.oxfordjournals.org/open_access.html for further details)

References

- Barrôco RM , Van Poucke K , Bergervoet JHW , De Veylder L , Groot SPC , Inze D , Engler G . 2005. The role of the cell cycle machinery in resumption of postembryonic development Plant Physiology 137 127–140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benech-Arnold RL. 2004. Inception, maintenance, and termination of dormancy in grain crops: physiology, genetics, and environmental control . In: Benech-Arnold RL, Sanchez RA. , eds, Handbook of seed physiology; applications to agriculture Binghamton: NY: Food Products Press; , pp 169–198 [Google Scholar]

- Benech-Arnold RL , Giallorenzi MC , Frank J , Rodríguez V . 1999. Termination of hull-imposed dormancy in barley is correlated with changes in embryonic ABA content and sensitivity Seed Science Research 9 39–47 [Google Scholar]

- Benech-Arnold RL , Gualano N , Leymarie J , Côme D , Corbineau F . 2006. Hypoxia interferes with ABA metabolism and increases ABA sensitivity in embryos of dormant barley grains Journal of Experimental Botany 57 1423–1430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berckmans B , De Veylder L . 2009. Transcriptional control of the cell cycle Current Opinion in Plant Biology 12 599–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bewley JD . 1997. Seed germination and dormancy The Plant Cell 9 1055–1066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bewley JD Black M. 1994. Seeds: physiology of development and germination New York:Plenum Press [Google Scholar]

- Bino RJ , Lanteri S , Verhoeven HA , Kraak HL . 1993. Flow cytometric determination of nuclear replication stages in seed tissues Annals of Botany 72 181–187 [Google Scholar]

- Cho H-J , Kwon H-K , Wang M-H . 2009. Expression of Kip-related protein 4 gene (KRP4) in response to auxin and cytokinin during growth of Arabidopsis thaliana BMP Reports 43 273–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbineau F , Côme D . 1996. Barley seed dormancy Bios Boissons Conditionnement 261 113–119 [Google Scholar]

- Corbineau F , Côme D . 2000. Dormancy of cereal seeds as related to embryo sensitivity to ABA and water potential. In: Viémont JD, Crabbé J, eds, 2nd international symposium on plant dormancy Oxon: CAB International; pp 183–194 [Google Scholar]

- De Castro RD Bino RJ Jing HC Keift H Hilhorst HWM. 2001. Depth of dormancy in tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) seeds is related to the progression of the cell cycle prior to the induction of dormancy Seed Science Research 11,45–54 [Google Scholar]

- De Veylder L , Beeckman T , Beemster GT , Krols L , Terras F , Landrieu I , van der Schueren E , Maes S , Naudts M , Inzé D . 2001. Functional analysis of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors of Arabidopsis The Plant Cell 13 1653–1668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Veylder L , Beeckman T , Inzé D . 2007. The ins and outs of the plant cell cycle Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 8 655–665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Veylder L , de Almeida Engler J , Burssens S , Manevski A , Lescure B , Van Montagu M , Engler G , Inze D . 1999. A new D-type cyclin of Arabidopsis thaliana expressed during lateral root primordia formation Planta 208 453–462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewitte W , Murray JAH . 2003. The plant cell cycle Annual Review of Plant Biology 54 235–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feurtado JA , Kermode AR . 2007. A merging of paths: abscisic acid and hormonal cross-talk in the control of seed dormancy maintenance and alleviation. In: Bradford KJ, Nonogaki H, eds, Seed development, dormancy and germination Oxford: Blackwell Publishing; pp 176–223 [Google Scholar]

- Galbraith DW , Harkins KR , Maddox JM , Ayres NM , Sharma DP , Firoozabady E . 1983. Rapid flow cytometric analysis of the cell cycle in intact plant tissues Science 220 1049–1051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gendreau E , Romaniello S , Barad S , Leymarie J , Benech-Arnold R , Corbineau F . 2008. Regulation of cell cycle activity in the embryo of barley seeds during germination as related to grain hydration Journal of Experimental Botany 59 203–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genschik P , Criqui MC , Parmentier Y , Derevier A , Fleck J . 1998. Cell cycle-dependent proteolysis in plants. Identification of the destruction box pathway and metaphase arrest produced by the proteasome inhibitor mg132 The Plant Cell 10 2063–2076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gornik K , De Castro RD , Liu Y , Bino RJ , Groot SPC . 1997. Inhibition of cell division during cabbage (Brassica oleracea L.) seed germination Seed Science Research 7 333–340 [Google Scholar]

- Gubler F , Hughes T , Waterhouse P , Jacobsen J . 2008. Regulation of dormancy in barley by blue light and after-ripening: effects on abscisic acid and gibberellin metabolism Plant Physiology 147 886–896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inzé D , De Veylder L . 2006. Cell cycle regulation in plant development Annual Review of Genetics 40 77–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joubès J , Chevalier C , Dudits D , Heberle-Bors E , Inze D , Umeda M , Renaudin JP . 2000. CDK-related protein kinases in plants Plant Molecular Biology 43 607–620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koroleva OA , Tomlinson M , Parinyapong P , Sakvarelidze L , Leader D , Shaw P , Doonan JH . 2004. CycD1, a putative G1 cyclin from Antirrhinum majus, accelerates the cell cycle in cultured tobacco BY-2 cells by enhancing both G1/S entry and progression through S and G2 phases The Plant Cell 16 2364–2379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanteri S , Saracco F , Kraak HL , Bino RJ . 1994. The effect of priming on nuclear replication activity and germination of pepper (Capsicum annuum) and tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) seeds Seed Science Research 4 81–87 [Google Scholar]

- Lenoir C , Corbineau F , Côme D . 1983. Principales caractéristiques de la dormance de l’Orge de brasserie et de son élimination Bios 14 24–29 [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y , Bergervoet JHW , de Vos CHR , Hilhorst HWM , Kraak HL , Karssen CM , Bino RJ . 1994. Nuclear replication activities during imbibition of gibberellin- and abscisic acid-deficient tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) mutant seeds Planta 194 378–373 [Google Scholar]

- Meijer M Murray JAH. 2000. The role and regulation of D-type cyclins in the plant cell cycle Plant Molecular Biology 43 621–633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menges M , de Jager SM , Gruissem W , Murray JA . 2005. Global analysis of the core cell cycle regulators of Arabidopsis identifies novel genes, reveals multiple and highly specific profiles of expression and provides a coherent model for plant cell cycle control The Plant Journal 41 546–566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millar AA , Jacobsen JV , Ross JJ , Helliwell CA , Poole AT , Scofield G , Reid JB , Gubler F . 2006. Seed dormancy and ABA metabolism in Arabidopsis and barley: the role of ABA 8'-hydroxylase The Plant Journal 45 942–954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nambara E , Marion-Poll A . 2003. ABA action and interactions in seeds Trends in Plant Science 8 213–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nambara E , Okamoto M , Tatematsu K , Yano R , Seo M , Kamiya Y . 2010. Abscisic acid and the control of seed dormancy and germination Seed Science Research 20 55–67 [Google Scholar]

- Oakenfull EA , Riou-Khamlichi C , Murray JA . 2002. Plant D-type cyclins and the control of G1 progression. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London Series B, Biological Sciences 357 749–760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Özbingöl N , Corbineau F , Groot SPC , Bino RJ , Côme D . 1999. Activation of cell cycle in tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) seeds during osmoconditioning as related to temperature and oxygen source Annals of Botany 84 245–251 [Google Scholar]

- Pines J . 1995. Cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases: a biochemical view The Biochemistry Journal 308 697–711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Planchais S , Glab N , Inze D , Bergounioux C . 2000. Chemical inhibitors: a tool for plant cell cycle studies FEBS Letters 476 78–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Planchais S , Samland AK , Murray JA . 2004. Differential stability of Arabidopsis D-type cyclins: CYCD3;1 is a highly unstable protein degraded by a proteasome-dependent mechanism The Plant Journal 38 616–625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggiero B , Koiwa H , Manabe Y , Quist TM , Inan G , Saccardo F , Joly RJ , Hasegawa PM , Bressan RA , Maggio A . 2004. Uncoupling the effects of abscisic acid on plant growth and water relations. Analysis of sto1/nced3, an abscisic acid-deficient but salt stress-tolerant mutant in Arabidopsis Plant Physiology 136 3134–3147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez MP , Gurusinghe SH , Bradford KJ , Vázquez-Ramos JM . 2005. Differential response of PCNA and Cdk-A proteins and associated kinase activities to benzyladenine and abscisic acid during maize seed germination Journal of Experimental Botany 56 515–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson GM . 1990. Seed dormancy in grasses Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; [Google Scholar]

- Sliwinska E . 2000. Analysis of the cell cycle in sugarbeet seed during development, maturation and germination. In: Black M, Bradford KJ, Vázquez-Ramos J, eds, Seed biology. Advances and applications Oxford: CAB International; 133–139 [Google Scholar]

- Sliwinska E . 2003. Cell cycle and germination of fresh, dried and deteriorated sugarbeet seeds as indicators of optimal harvest time Seed Science Research 13 131–138 [Google Scholar]

- Sorrell DA , Marchbank A , McMahon K , Dickinson JR , Rogers HJ , Francis D . 2002. A WEE1 homologue from Arabidopsis thaliana Planta 215 518–522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swiatek A Lenjou M Van Bockstaele D Inzé D Van Onckelen H. 2002. Differential effect of jasmonic acid and abscisic acid on cell cycle progression in tobacco BY-2 cells Plant Physiology 128,201–211 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandepoele K , Raes J , De Veylder L , Rouzé P , Rombauts S , Inzé D . 2002. Genome-wide analysis of core cell cycle genes in Arabidopsis The Plant Cell 14 903–916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez-Ramos JM Sánchez MP. 2003. The cell cycle and seed germination Seed Science Research 13,113–130 [Google Scholar]

- Verwoerd TC , Dekker BM , Hoekema A . A small-scale procedure for the rapid isolation of plant RNAs. Nucleic Acids Research. 1989;17:2362. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.6.2362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H , Qi Q , Schorr P , Cutler AJ , Crosby WL , Fowke LC . 1998. ICK1, a cyclin-dependent protein kinase inhibitor from Arabidopsis thaliana interacts with both Cdc2a and CycD3, and its expression is induced by abscisic acid The Plant Journal 15 501–510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.