Abstract

To compare elliptical excision with primary midline closure and rhomboid excision with limberg flap reconstruction techniques for the sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus. This prospective randomized study of 80 patients of sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus was performed in SKIMS medical college from 2004 to 2007. After assigning patients randomly to either of the surgical groups, group A patients (40/80) were operated by using rhomboid excision with limberg flap reconstruction whereas group B patients (40/80) were operated by using elliptical excision with primary midline closure. Data was compiled in terms of operative period required, immediate post operative complications, post operative pain (VAS scores), work-off period, hospital stay and recurrences over a follow up of 3 years for the two study groups. Data thereby collected was analyzed by using Microsoft excel. The parameters in which the two techniques were found to differ significantly were work-off period, immediate post operative complications profiles and recurrence rates. Rhomboid excision with limberg flap reconstruction technique surely outscores elliptical excision with primary midline closure in certain important parameters. While facing a patient with uncomplicated sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus, instead of, which procedure for the patient? Surgeons should pose the question why not rhomboid excision with limberg flaps reconstruction?

Keywords: Sacrococcygeal, Pilonidal sinus, Limberg flap

Introduction

Pilonidal sinus is a blind track, which extends from the skin of natal cleft up to the presacral fascia. An attribute of “pilonidal” to this particular sinus is to emphasize its unique feature of the presence of tufts of hair within it. The etiology of the sinus has been hypothesized variously whereby the congenital theory of its origin yielded to the acquired nature of the condition in the twentieth century when the sinus cropped up in jeep-drivers during World War II. Presence of tufts of hair within the sinus in around 60% of the cases is now considered important secondary event in the evolution of the sinus. A pilosebaceous unit primed by male sex hormones in young adult males at the peculiar sacrococcygeal prominence with its mouth wide open to receive hair shafts seems a pleasing theory for explaining the acquired model for the disease [1]. The model seems to provide place for various predisposing factors for sinus such as bumping in sitting posture, excessive healthy body hair, obesity, family history, and Caucasian ethnicity.

Patients and Methods

After proper ethical committee approval for the study, a total of 80 patients with sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus were enrolled from 2004 to 2007. After informed consent from the patients, a surgical procedure of “excision with primary midline closure” was applied to 40 patients, while “rhomboid excision with Limberg flap reconstruction” was used in other 40 patients of the study. Patients were randomly assigned to one of the surgical groups, and all patients were operated electively in prone position under local anesthesia only. Patients with recurrent disease and purulent discharge were excluded from the study. Preoperative hair shave of the part was done on the day of surgery, and all patients received ceftriaxone 1 g intravenously before shifting to the theater. Buttocks were retracted using adhesive tape to obtain a better visualization of the operative field. After skin preparation, the anus was excluded from the area with surgical drapes.

Excision with Primary Closure

The external opening of the sinus was gently cannulated by a stile, and methylene blue was injected through the external opening of the sinus tract. Thereafter, all tracts were excised by a vertical elliptical incision up to the presacral fascia. After appropriate hemostasis, the defect was closed by interrupted 0 polyglactin (VicrylTM; Ethicon) and the skin edges approximated with 3-0 polypropylene (ProleneTM; Ethicon).

Rhomboid Excision with Limberg Flap

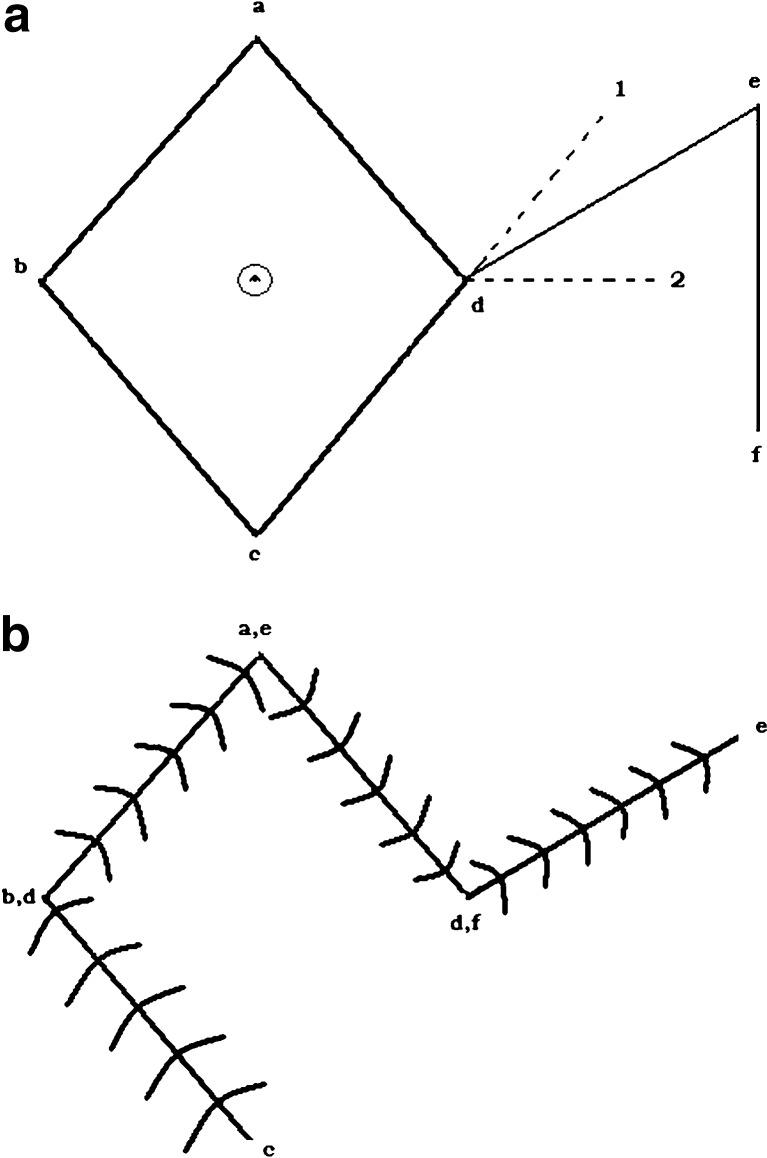

The skin was marked by a marker pen and after methylene blue injection; the involved area was excised by a rhomboid excision (abcd, Fig. 1a). An incision line de equal to the sides of rhomboid was created midway between extension of line cd and the horizontal axis. Another incision ef of the same length was made on the vertical axis to raise a fasciocutaneous rhomboid Limberg flap (cdef). This flap was transposed to the excised area. Subcutaneous tissue and skin were sutured separately without tension using polyglactin and polypropylene interrupted sutures (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

Sketch diagram of rhomboid flap

Operative period was recorded from the time of incision to the completion of wound closure. Wounds were closed without using any kind of drains. Patients were allowed orals after 2–4 h of surgery. Postoperatively, pain was evaluated by visual analog scale and the number of analgesic doses (oral diclofenac sodium) required. Postoperative hospital stay was noted with the day of surgery being day zero. Daily wound care was performed for each individual. Skin sutures were removed on the eighth postoperative day. Follow-up was done after 1, 2, and 4 weeks and 3, 6, and 12 months for the first year after surgery. After the first year, patients were followed yearly for consequent 2 years to conclude a total of 3 years of follow-up.

Data were collected and managed using Microsoft Excel. Unpaired Student’s t-test was used to determine the significance of the difference between two independent groups among continuous variables. For qualitative data, Chi square test was used to see the significant difference in proportion between two groups. A p value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

The study consisted of 74 males (92.5%) and 6 females (7.5%), with a mean age of 28.4 ± 8.6 years (range 16–48 years). Excision with primary midline closure was performed in 40 patients (36 males and 4 females), and rhomboid excision with Limberg flap reconstruction was performed in the other 40 patients (38 males and 2 females) of the study. The mean duration of symptoms was 12.2 months (range 2–23 months). The operative time (minutes) and hospital stay (days) for the primary closure group were 43.50 ± 10.60 and 2.30 ± 1.56 whereas the corresponding values for the Limberg flap group were 47.62 ± 9.30 and 1.77 ± 1.30, respectively, with p values of >0.05 between two groups for both the parameters. The work off period (days) for the primary closure group was 12.52 ± 1.87 against 10.80 ± 3.25 for the Limberg flap group (p = 0.0048). Table 1 compares complication profiles for the two groups of the patients. The VAS scores for the primary closure group were 4.21 (day 1), 2.01 (day 2) against 3.78 (day 1), 1.86 (day 2) for the Limberg flap group with insignificant p values of >0.05. Diclofenac sodium (mg) required for the primary closure group was 175 (mean), while the requirement for the Limberg flap group was 105 with a p value of 0.238.

Table 1.

Post-operative complication profile for the two study groups

| Primary closure (n = 40) | Limberg flap (n = 40) | |

|---|---|---|

| Supurative wound infection | 5(12.5%) | 2(5%) |

| Hematoma/Seroma | 1(2.5%) | 3(7.5%) |

| Wound Disruption | 2(5%) | 0 |

| Recurrence | 3(7.5%) | 0 |

Discussion

Although certain nonsurgical treatment options for treating the condition are still available, but now the consensus for treating it surgically has evolved. A full basket of techniques ranging from simple curette to extensive flap techniques have been published so far. Conceptually, an ideal procedure, in addition to eradicating the disease, should also eliminate the natal cleft so as to take off the anatomical predisposition for the recurrence of the sinus. The procedure should also count well on other parameters such as technical simplicity, hospitalization period required, and off work period. However, none of the techniques have been established to be superior over others in all aspects. Comparative studies of the various procedures are being increasingly published for documenting the relative superiority of one over the other.

Impact of a procedure on the recurrence of the sinus probably depends mainly on the ability of the procedure to tease the depth of natal cleft. Leftover primary residual sinus tracts, a dead space which opens at the gravitational pit of the cleft, regularity of the hair shave of the cleft, and obesity also have an undoubted contribution to the recurrence of the sinus. So, looking that way one expects flap procedures to combat the disease recurrence better than excision with simple closure, keeping in view extensive dissection of the sinus tracts and the shallower cleft that flap procedures provide. Literature has documented a recurrence rate of 0–3% [2–6] for Limberg flap against a significantly high recurrence of 7–42% [7, 8] for primary closure. Outcome of our study in terms of recurrence of the sinus is the same as reported by other studies, namely, three recurrences for the primary closure group against zero recurrence of the Limberg flap group. Fist, a drawback of follow-up of less than 3 years for documenting the recurrence mars the such data of many of the studies since most of the recurrences present within 3 years of the primary procedure [9, 10]. Second, most of the published studies have failed to define recurrence and the second occurrence of the disease. A true recurrence opens at the previous operative scar, otherwise it should define as the second occurrence [11]. However, such confounding probably is least likely to change the published relative recurrence profiles of the procedures, keeping in view the fact that a recurrence is more likely to be a second occurrence in case of a flap procedure than the primary closure technique as in latter scars are oriented longitudinally in the cleft.

The consideration of a financial burden in the surgical management of pilonidal sinus assumes more importance because the disease is an affliction of mainly the second and third decades of life. Published data reveal 7–17.5 days [6, 12, 13] work off period for the Limberg flap and 21–23 days [11, 14] for the midline primary closure. In keeping with these results, our study also documented a less work off period for the Limberg flap group (mean 10.80 ± 3.25; range 7–15 days) as compared to the primary closure group (mean 12.52 ± 1.87; range 8–17 days) and the difference has been found to be statistically significant with a p value of 0.0048.

Literature documents a hospital stay of 1–5 days and 2–4 days for the primary midline closure and Limberg flap techniques, respectively. We observed a total hospital stay of 2.30 ± 1.56 days and 1.77 ± 1.30 days for the primary midline closure group and the Limberg flap group, respectively. Although substantial material has been published on the Limberg flap technique for pilonidal sinus, there is only little documentation of the operative period for the technique. Akca et al. have documented a median operative period 60 min for the Limberg flap group against 45 min for the primary midline closure group, and the difference has been found to have p value of 0.001 [15]. Whereas Abu Galala et al. have observed an insignificant difference in the operative time periods of the two techniques [11]. Our study also documented a statistically nonsignificant difference between operative time periods for the two procedures; a mean of 43.50 ± 10.60 (range 30–65) minutes for primary midline closure against 47.62 ± 9.30 (range 40–70) minutes for Limberg flap. Near similar values of these parameters (operative time and total hospital stay) for the two procedures should render them a less important factor in determining the relative superiority of one procedure over the other. Raising Limberg flap with gluteal fascia and suturing it with the presacral fascia, avoiding use of drains in flap procedure, and performance of the procedure by surgeons relatively more frequently might account for the both decreasing the operative time and total hospital stay for the Limberg flap.

A thorough look at the immediate postoperative complication profile of the two procedures leads to the conclusion that wound collections (hematoma/seroma) tend to occur with Limberg flaps whereas suppurative wound infections, wound disruptions, and postoperative pain tend to occur more with midline primary closure procedure. Such differential tendencies for the two procedures are accounted by the extensive dissection for the flap procedure and strained wound at the basin of natal cleft for the primary midline closure. Published studies documented a wound infection rate and a wound disruption rate of up to 12.4% [16] and 5–10% [15, 17], respectively, for the primary midline closure technique, while published values of such parameters for the Limberg flap group are 1.5–6.5% [4, 6, 15, 18] and 0.9–3.9% [18, 19], respectively. In keeping with the published literature, our study observed an immediate complication rate of 20% (suppurative wound infections or wound disruptions 7/40 and hematoma or seroma 1/40) and 12% (suppurative wound infections 2/40 and hematoma or seroma 3/40) for the primary midline closure group and the Limberg flap group, respectively. From these data, it is evident that a more morbid immediate postoperative complication profile has been established for the primary closure group than with the Limberg flap group. Does a postoperative indoor patient strategy prevent these complications or at least make them less morbid; is a concern to be weighed? Data are unavailable on the proportion of patients who would actually benefit from postoperative indoor strategy for preventing their immediate postoperative complications. Presumably, it seems that the proportion will be too less to be cost-effective for the procedure, keeping in view the over all immediate complication rates for the procedure and management protocols for such complications. Such discussion might provide an overnight postoperative stay and an OPD visit after 48 h of discharge an effective alternative to the postoperative indoor strategy. Similar to the results of other studies, a significantly higher rate of seroma/hematoma formation in the Limberg flap group (3/40) as compared to the primary closure group (1/40) is attributed to the relatively extensive dissection involved in flap procedures, whereas more pain VAS scores for the latter than the former technique are attributed to more wound tension associated with the latter technique.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interest

None

Financial support

None

References

- 1.Bascom JU. Pilonidal disease: correcting overtreatment and under treatment. Contemporary Surg. 1981;18:13–28. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Azab AS, Kamal MS, Bassyoni F. The rationale of using the rhomboid fasciocutaneous transposition flap for the radical cure of pilonidal sinus. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1986;12:1295–1299. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1986.tb01070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mentes BB, Leventoglu S, Cihan A, et al. Modified Limberg transposition flap for sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus. Surg Today. 2004;34:419–423. doi: 10.1007/s00595-003-2725-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eryilmaz R, Sahin M, Alimoglu A, et al. Surgical treatment of sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus with Limberg transposition flap. Surgery. 2003;134:745–749. doi: 10.1016/S0039-6060(03)00163-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kapan M, Kapan S, Pekmezci S, et al. Sacrococygeal pilonidal sinus disease with Limberg flap repair. Tech Coloproctol. 2002;6:27–32. doi: 10.1007/s101510200005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Topgul K, Ӧzdemir E, Kilic K, et al. Long term results of Limberg flap procedure for the treatment of pilonidal sinus: A report o 200 cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:1545–1548. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6811-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sondenaa K, NesvikI AE, et al. Bacteriology and complications of pilonidal sinus treated with excision and primary closure. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1995;10:161–166. doi: 10.1007/BF00298540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iesalnieks I, Furat A, Rentsch M, et al. Primary mid line closure after excision of pilonidal sinus is associated with high recurrence rate. Chirurg. 2003;74:461–468. doi: 10.1007/s00104-003-0616-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kronborg O, Christensen K, Zimmermann-Nielsen C. Chronic pilonidal disease: a randomised trial with a complete 3-year follow-up. Br J Surg. 1985;72:303–304. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800720418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aydede H, Erhan Y, Sakarya A, et al. Comparison of three methods in surgical treatment of pilonidal disease. Aust N Z J Surg. 2001;71:362–364. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1622.2001.02129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abu Galala KH, Salam IM, Abu Samaan KR, et al. Primary closure with a transposed rhomboid flap compared with deep suturing: a prospective randomised clinical trial treatment of pilonidal sinus. Eur J Surg. 1999;165:468–472. doi: 10.1080/110241599750006721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Urhan MK, Kucukel F, Topgul K, et al. Rhomboid excision and Limberg flap for managing pilonidal sinus: results of 102 cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:656–659. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6263-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bozkurt MK, Tezel E. Management of pilonidal sinus with the Limberg flap. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41:775–777. doi: 10.1007/BF02236268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khaira HS, Brown JH. Excision and primary suture of pilonidal sinus. Ann R Coll Surg Eng. 1995;77:242–244. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Akca T, Colak T, Ustunsoy B, et al. Randomised clinical trial comparing primary closure with the Limberg flap in the treatment of primary sacrococygeal pilonidal disease. Br J Surg. 2005;92:1081–1084. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Petersen S, Koch R, Stelzner S, et al. Primary closure techniques in chronic pilonidal sinus: a survey of results of different surgical approaches. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:1458–1467. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6451-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee HC, Ho YH, Seow CF, et al. Pilonidal disease in Singapore: clinical features and management. Aust N Z J Surg. 2000;70(3):196–198. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1622.2000.01785.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mentes O, Bagci M, Bilgin T, et al. Limberg flap procedure for pilonidal sinus disease: results of 353 patients. Langen Becks Arch Surg. 2008;393(2):185–189. doi: 10.1007/s00423-007-0227-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kabukcu A, Gonullu NN, Paksoy M, et al. The role of obesity on the recurrence of pilonidal sinus disease patients, who were treated by excision and Limberg flap transposition. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2000;15:173–175. doi: 10.1007/s003840000212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]