ABSTRACT

PURPOSE

To explore the factors influencing primary care providers’ ability to care for their dying patients in Michigan.

METHODS

We conducted 16 focus groups to explore the provision of end-of-life care by 7 diverse primary care practices in southeast Michigan. Twenty-eight primary care providers and 22 clinical support staff participated in the study. Interviews were analyzed using thematic analysis.

RESULTS

Primary care providers (PCPs) wanted to care for their dying patients and felt largely competent to provide end-of-life care. They and their staff reported the presence of five structural factors that influenced their ability to do so: (1) continuity of care to help patients make treatment decisions and plan for the end of life; (2) scheduling flexibility and time with patients to address emergent needs, provide emotional support, and conduct meaningful end-of-life discussions; (3) information-sharing with outside providers and within the primary care practice; (4) coordination of care to address patients’ needs quickly; and (5) authority to act on behalf of their patients.

CONCLUSIONS

In order to provide end-of-life care, PCPs need structural supports within primary care for continuity of care, flexible scheduling, information-sharing, coordination of primary care, and protection of their authority.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11606-012-2088-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

KEY WORDS: primary care practice, palliative care, end of life, qualitative

INTRODUCTION

Despite primary care’s commitment to comprehensiveness and continuity,1 there is reason to believe few Americans die under the stewardship of a familiar primary care provider (PCP). While the exact numbers who die under a PCP’s care are unknown, it is known that 70 % of Americans die in hospitals or other institutions2 where increasingly fewer PCPs follow their patients.3–6 Moreover, many patients and family caregivers report feelings of abandonment by physicians at the time of death.7–9 This reality is in stark contrast to the wish many patients have to die at home10,11 and under the care of their personal physician.12–14

Primary care at the end of life not only benefits the patient, but also the health system. At the end of life, greater continuity with primary care is associated with fewer avoidable hospitalizations,15 less emergency department use,16 and increased out-of-hospital death in cancer patients.17 In the UK, where 90 % of the care of dying patients during the last year of life is supervised by a general practitioner,18,19 less money is spent per person for all the care received after age 65,20 and fewer people die using intensive care.21

Two recent developments promise to change both access to and delivery of primary care in the US. First, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act22 expands the access Americans have to PCPs by mandating health insurance coverage and expanding the primary care workforce. Second, the Primary Care Medical Home (PCMH), which emphasizes comprehensive, continuous, and coordinated care, is becoming a dominant model of primary care delivery.23–26 While currently little is known about the processes involved in the delivery of end-of-life care by PCPs,27 a better understanding of these processes may inform how care for dying patients can be improved as primary care evolves.

In this vein, we conducted a qualitative study to describe how PCPs currently provide end-of-life care for their patients who have life-limiting conditions in order to describe the process of care and identify areas for practice improvement. We were particularly interested in how PCPs and their staff addressed the physical, psychological, and social needs of their patients within the confines of a busy practice and how the structure of care (prior to reform) presented challenges to PCPs’ ability to provide good end-of-life care. We used qualitative methods because they are oriented toward understanding complex social environments and mechanisms underlying outcomes.28 To our knowledge, ours is the only qualitative study of US PCPs that focuses on issues related to the delivery of end-of-life care by PCPs.

METHODS

Design, Sampling, and Participants

We gathered information through in-depth focus group interviews with PCPs and the staff of seven primary care practices in southeast Michigan. Clinic directors at each site served as key informants who introduced the study concept to potential participants who were then recruited by a research assistant. To qualify for the study, interviewees (PCPs = MD, DO, or NP; affiliated clinical support staff = LPN, RN, or MA) had to work in one of the practices selected and had to have experienced the death of at least one patient in the last year. Potential participants were excluded if they were actively participating on a palliative care or hospice team (since they would not be as representative of the norm).

Primary care practices were identified by the lead author using their affiliation with the five largest medical centers serving the community. Within these centers, individual practices were sampled using maximum variation to include a variety of practice settings (hospital based vs community based), specialty (family medicine vs general internal medicine), patient populations (urban vs suburban, affluent vs poor, racially diverse vs primarily white), and practice type (small private practice vs multispecialty clinic). We used maximum variation sampling so we could identify common themes across diverse settings.29 Clinic directors from each practice consented to their staff’s involvement.

Data Collection

Focus groups were held at the study sites. We conducted focus groups rather than individual interviews because, as we were trying to understand systems and processes of care, we felt that the validity of our data would be increased by real-time discussion that allowed us to cross check across participants.30 We conducted focus groups with both PCPs and clinical support staff from the same practice to gain more holistic and valid accounts of end-of-life care in each practice. Primary care providers and clinical support staff were interviewed separately to promote candor and comfort.

Due to the busy schedules of interviewees as well as the small size of each practice, focus groups ranged from two to five participants. Smaller focus group size allowed for in-depth discussion. Participants received a snack and a nominal honorarium for their time.

The same, doctorally trained, and experienced professional moderator conducted all focus groups. One of the authors (JF) served as an assistant moderator for most of the focus groups to provide detailed knowledge of end-of-life care when necessary. Each focus group was a single event lasting 90 min. At the opening of each focus group, participants were asked to reflect on the last patient who died under their care, focusing specifically on the care of adults with ‘chronic, progressive, life-limiting conditions.’ Follow-up questions were used to flush out the needs of their dying patients and how those were addressed, with attention in subsequent discussion to barriers and facilitators to good care, as well as interviewees’ recommendations for change (see Online Appendix for focus group guide).

Data Analysis

All focus groups were audio-taped and transcribed verbatim. To assess the reliability of transcription, a subset of transcripts was compared against the original recordings.

Data analysis was conducted in an iterative fashion using constant comparison31 to develop codes. Two senior researchers experienced in qualitative research (MJS, JF) reviewed the first four transcripts from the first two sites to generate analytically meaningful categories, or “codes.” They refined these codes and their definitions over several meetings through iterative coding of the same data. The coding scheme was finalized by the third and fourth study sites. At that point, two research assistants were instructed in its use, and each coded the first ten transcripts (including the 4 used to generate the coding scheme). Double coding of the first ten transcripts was done to insure proper and uniform application of the coding scheme. Discrepancies were resolved through team discussion and consensus;31 conflicts were resolved by deferring to the Principal Investigator. The remaining six transcripts were coded by one coder each.

The coded transcripts were entered into NVivo 7© software (2006, QSR International) to facilitate data analysis. Senior researchers (MJS, JF) reviewed the code reports for all 16 focus groups and conducted within-case and cross-case analysis to develop themes32 that were presented to the entire research team to check face validity.

Human Subject Concerns

The study was fully reviewed and approved by the institutional review boards at the University of Michigan, the Ann Arbor Veterans Administration Medical Center, and each hospital-affiliated study site. All interviewees provided informed consent.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

We conducted 16 focus groups in 5 general internal medicine and 2 family medicine practices serving diverse communities throughout southeast Michigan. Descriptions of the seven practices are available in the Online Appendix. Twenty-eight PCPs (19 internists, 7 family physicians, and 2 nurse practitioners) and 22 clinical support staff (10 registered nurses, 9 licensed practical nurses, and 3 medical assistants) participated in the focus groups. PCPs described being responsible for managing acute and chronic illnesses; internists primarily cared for geriatric patients (although none sub-specialized in geriatrics), while family physicians cared for pediatric and obstetric patients as well. Support staff roles varied by practice―from answering telephones, to checking in patients, case managing, nursing, and social work.

Primary Care for Dying Patients

The ability to care for patients at the end of life was largely dependent upon continuity (i.e., the continued relationship with the patient after diagnosis), which, in turn, was highly influenced by the nature of the patient’s diagnosis. Patients with non-cancer diagnoses typically maintained continuity with their PCPs until death or enrollment in hospice. Patients with cancer, on the other hand, were largely “lost to follow-up” and received end-of-life care from oncologists. Some PCPs regretted this occurrence:

The oncologists often manage a lot of the other issues having to deal with their health without my input necessarily…I tend to see less of my cancer patients than what I’m comfortable with.

However, other PCPs felt that cancer patients should be managed primarily by oncologists in order to limit patient travel and because oncologists had the expertise to manage such patients.

Occasionally, cancer patients did maintain continuity with their PCP while concurrently receiving treatment from oncologists. This occurred when the PCP insisted on follow-up or when the patient had other chronic illnesses the oncologist preferred not to manage. PCP attitudes toward maintaining contact varied, even within the same practice.

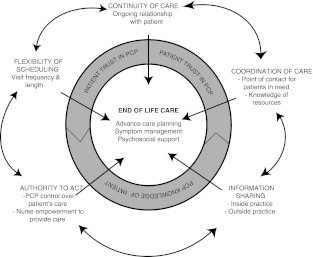

Overall, PCPs largely felt comfortable providing the end-of-life care themselves without the support of palliative care consultation. Still, they cited five structural factors that affected their ability to address the needs of patients with life-limiting conditions. Figure 1 shows how these structural factors relate to the provision of end-of-life care, as well as to each other.

Figure 1.

Schematic of themes and interrelationships identified in study.

Continuity of Care

Participants reported that a continued relationship with their patients facilitated decision-making and planning for the end of life. Continuity allowed the PCP to know the patient as a whole person. With deep knowledge of the patient, the PCP could provide information and cast recommendations within a context that patients and families could relate to. By so doing, the physician fostered trust and helped patients and families feel comfortable with treatment decisions. Trust and comfort were particularly important for decisions about withholding or withdrawing treatment.

They want their doctor to say that it’s okay. They trusted me for ten years—-if I say ‘Good,’ they’ll unflinchingly trust. They just want to make sure that the [treatment] program has got my blessing.

Knowledge of the patient as a whole person also contributed to the PCP’s ability to respond appropriately to patient and family needs, such as pain and emotional issues.

Scheduling Flexibility and Time

PCPs needed flexibility in their schedule to allow timely visits for addressing emerging needs, such as symptoms. When physicians’ schedules allowed for booking appointments on short notice, patients were often prevented from resorting to emergency or urgent care. When schedules were set months in advance, however, patients ended up in urgent care.

[Urgent care is] used because [patients] might not be able to get an appointment with a provider… [A problem] becomes even more urgent and they just go to urgent care.

Most providers felt they needed longer and more frequent visits to develop the knowledge of the patient necessary to provide emotional support and conduct meaningful end-of-life conversations.

With time and a number of visits I’m establishing a rapport with someone so I can bring up [psychosocial issues] in conversation.

Without time, physicians prioritized physical needs over psychosocial ones; advance care planning was especially affected when there were competing demands on clinicians’ time.

Information-Sharing

Clinicians’ ability to know their patients and provide meaningful guidance hinged on access to the right information from outside providers. Contextualized, prognostic information was necessary to know how to present treatment options and guide patients though decision-making about CPR and life support, as well as when to refer to hospice.

The piece that I would probably welcome most is somebody who had the knowledge to help the patient and the family and I understand the prognosis and then be able to be part of a fairly technical conversation about options.

When such information could not be gleaned from medical records, some providers would “call up [subspecialists] in order to have that kind of communication.”

Information-sharing within the practice allowed clinical staff to know how to apply their expertise to make referrals, call in prescriptions, and offer basic recommendations for symptom management.

[The nurse] is aware of the diagnosis, she's aware of what we're doing, and she's calling as a prophylactic check in, If I say, ‘Mrs. Jones needs X Y Z.’ They’re like, ‘Oh, yeah. I talked to her yesterday.’ So, it makes it easier.

When good within-practice information-sharing did not exist, PCPs bore the brunt of responsibility for coordination of care and did not benefit from existing nurse support.

Coordination of Care

Coordination of care was central to providing timely and robust end-of-life care. Coordination of care involved gathering all the necessary information about a patient’s history, status, and prognosis, as well as arranging referrals to other providers (such as hospice), providing medications, and accessing community services. This activity was time consuming, taking physicians away from more pressing concerns; “Can you imagine doing [social worker]'s job on top of everything else you do?” Thus, many providers relied on support staff to coordinate care; one practice even took resources originally budgeted for physician time to hire a full-time social worker instead.

Sites with good coordination of care had a point person who could be easily reached by patients, was familiar with the patient’s history and status, had some clinical and social work skills, and was empowered to address the patient’s needs. At sites lacking such a contact person, PCPs and families largely bore the responsibility for coordinating care. Patients would show up in the clinic unannounced to get questions answered or crises addressed, and patient phone calls would be passed from person to person―creating a constant source of interruption and stress for staff, described by one staff member as “hanging on by our toenails.”

Authority to Act

Whether a physician or clinical staff member, participants needed authority—i.e., a sense of control or mastery over the patient’s care, in order to participate in the patient’s end-of-life care. Authority granted clinical support staff the independence to address patients’ needs without involving physicians. Authority allowed PCPs the freedom to counsel patients at the end of life on options such as hospice or comfort care.

The general internist is the primary ‘treater’ of the heart failure and that's where you'll see [us] start to make the hospice referrals in the clinic -because we're the person that's responsible for the care of that specific disease…We're really making those decisions with the patients.

PCPs needed subspecialists―oncologists in particular―to respect their place as the patient’s primary physician in order to maintain a meaningful role in the patient’s care. When PCPs actively asserted themselves with subspecialists, PCPs were the ones to break bad news, and make transitions in care and advanced care plans. On the other hand, when PCPs felt powerless to help their patients, they abdicated end-of-life care to subspecialists.

DISCUSSION

Primary care providers (PCPs) in our study wanted to care for their dying patients and largely felt competent to provide end-of-life care, but many faced obstacles related to five structural elements of the system in which they practiced: continuity of care, scheduling flexibility and time with patients, coordination of care, information-sharing, and authority to act. We found that the presence of these structures fostered patient trust in the physician and physician knowledge of the patient, which, in turn, were necessary for PCPs to address both the physical and psychosocial needs at the end of life. Interestingly, the elements physicians needed for providing good end-of-life care are elements germane to providing good primary care in general; i.e., no structural elements unique to the provision of palliative care were identified.

This study has its limitations. Because this was a qualitative study, our findings are not meant to be generalized to all primary care practices, but rather to provide insight into phenomena that cannot be studied quantitatively. There is the possibility of sample bias, as those individuals who volunteered for the focus groups could have been particularly sympathetic or antagonistic to the topic of inquiry. Moreover, primary care practices in southeast Michigan may not be illustrative of primary care practices elsewhere.

Additionally, the small size of some of our focus groups makes it more likely that one strong opinion could sway the tenor of discussion. There is also the possibility that focus group participants provided answers that were socially desirable or that their responses were influenced by cognitive dissonance; however, the spectrum of responses suggests that this was not common. Lastly, we did not directly observe providers in practice or collect data from patients, and so could not confirm providers’ self-reports.

Nevertheless, our findings resonate with the existing literature. Studies from Europe have shown that general practitioners value coordination, time, authority, and continuity.33–36 Studies in the US have shown that “role ambiguity” is a barrier to end-of-life care when multiple providers attend to the same patient,27 and that communication between primary care and subspecialists is inadequate.37,38 Additionally, the connections between continuity and trust,39 as well as continuity and physician knowledge40 have been demonstrated before.

Our data provide some clues as to how practices can overcome some of the barriers to providing end-of-life care. These include personal actions by PCPs, such as personally calling subspecialists to ask for prognostic information, or making structural changes to the practice, such as hiring a social worker. Still, the specific structures and processes that are put into place to address structural barriers will need to vary based on organizational context41 and practice type. A future study with an even larger purposive sample stratified by organizational and practice characteristics would be needed to produce a valid description of how these characteristics affect provision of end-of-life care.

Some might posit that advance directives could be used to delegate authority over end-of-life care to the PCP; however, it is important to remember that advance directives only come into play once patients have lost decisional capacity, while delegation of authority is an issue the entire time a patient is being cared for within a complex medical system.

Many of the factors we identified as crucial to providing end-of-life care are consistent with elements of the Patient Centered Medical Home (PCMH),23 which emphasizes patient access to care, care coordination, and smooth information transfer, both within the practice and with outside providers. Whether or not the PCMH model will allow PCPs to provide robust end-of-life care is a hypothesis worth future examination.

Having the means to provide robust end-of-life care does not guarantee that PCPs will provide the care. Across our panel of subjects, we saw variation in the sense of ownership of end-of-life care. How physician attitudes determine practice change or use of available supports is an important relationship that was not explored in this study. Moreover, while the PCPs in this study felt confident in their skills for providing end-of-life care, other studies have demonstrated that many lack those skills.42–44 Future qualitative work is necessary to understand how PCP knowledge and attitudes affect the willingness to put in place and use structures that facilitate good end-of-life care.

It is important to underscore that our results do not suggest that all five practice elements are necessary or that any one is sufficient for PCPs to provide end-of-life care. Moreover, the factors themselves are not binary in nature, but they can be present within a practice in varying degrees depending upon the characteristics of the practice. In-depth ethnographic work could shed more light on how these factors work together in various contexts to affect the quality and delivery of end-of-life care. Future research into how to measure these factors may provide tools necessary for practice evaluation and improvement, as well as statistical testing of relationships.

ELECTRONIC SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Appendix (DOC 39 kb)

Acknowledgements

Dr. Silveira’s salary was supported by a US Veterans Administration Career Development Award. Research costs were supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Generalist Scholars Program. Neither the US Veterans Administration nor the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation had any role in the design of the study, collection or analysis of data, or writing of this article.

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Silveira and Dr. Forman have no conflicts of interest related to this work.

Disclaimer

The authors alone are responsible for the views, opinions, and conclusions expressed herein.

Footnotes

Prior Presentations

Preliminary results of this research were presented as abstracts at the Society of General Internal Medicine meeting in New Orleans, LA, May 2005, and the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine meeting in Nashville, TN, February 2006.

References

- 1.Starfield B. Primary care: concept, evaluation, and policy. New York: Oxford University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Center for Health Statistics. Deaths by place of death, age, race, and sex: United States, 1999–2005. 2005; http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/mortality/gmwk309.htm. Accessed March 16, 2012.

- 3.Macguire P. Use of mandatory hospitalists blasted; ACP others protest plans that force doctors to give up inpatient care. ACP Internist: ASP-ASIM; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown RG. Hospitalist concept: another dangerous trend. Am Fam Physician. 1998. [PubMed]

- 5.Lo B. Ethical and policy implications of hospitalist systems. Am J Med. 2001;111(9B):48–52. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Bagley B. The hospitalist movement and family practice—an uneasy fit. J Fam Pract. 2002;51(12):1028–1029. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanson LC, Danis M, Garrett J. What is wrong with end-of-life care? Opinions of bereaved family members. JAGS. 1997;45(11):1339–1344. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb02933.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teno JM, Clarridge BR, Casey V, et al. Family perspectives on end-of-life care at the last place of care. JAMA. 2004;291(1):88–93. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.1.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Back AL, Young JP, McCown E, et al. Abandonment at the end of life from patient, caregiver, nurse, and physician perspectives: loss of continuity and lack of closure. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(5):474–479. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Palmer TA, Galanos AN, Hays JC. Preference for place of death among healthy elderly. JAGS. 1999;47(9):S50. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Townsend J, Frank AO, Fermont D, et al. Terminal cancer care and patients' preference for place of death: a prospective study. BMJ. 1990;301(6749):415–417. doi: 10.1136/bmj.301.6749.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steinhauser KE, Christakis NA, Clipp EC, et al. Factors considered important at the end of life by patients, family, physicians, and other care providers. JAMA. 2000;284(19):2476–2482. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.19.2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sisler JJ, Brown JB, Stewart M. Family physicians' roles in cancer care. Survey of patients on a provincial cancer registry. Can Fam Physician. 2004;50(6):889–896. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Michiels E, Deschepper R, Kelen G, et al. The role of general practitioners in continuity of care at the end of life: a qualitative study of terminally ill patients and their next of kin. Palliative Medicine. 2007;21(5):409–415. doi: 10.1177/0269216307078503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheng SH, Chen CC, Hou YF. A longitudinal examination of continuity of care and avoidable hospitalization: evidence from a universal coverage health care system. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(18):1671–1677. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burge F, Lawson B, Johnston G. Family physician continuity of care and emergency department use in end-of-life cancer care. Medical Care. 2003;41(8):992–1001. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200308000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burge F, Lawson B, Johnston G, Cummings I. Primary care continuity and location of death for those with cancer. J Palliat Med. 2003;6(6):911–918. doi: 10.1089/109662103322654794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.End of life care strategy: promoting high quality care for all adults at the end of life. London: National Health Service;2008.

- 19.Cartwright A. The role of hospitals in the last year of people's lives. Br J Hosp Med. 1992;47(11):801–803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duncan DE. Life at All Costs: Part One, The Mid-Death Crisis. The Fiscal Times. March 9, 2010; Life & Money.

- 21.Wunsch H, Linde-Zwirble WT, Harrison DA, et al. Use of intensive care services during terminal hospitalizations in England and the United States. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180(9):875–880. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200902-0201OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.United States Congress, House of Representatives. Compilation of Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act: as amended through November 1, 2010 including Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act health-related portions of the Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010. Washington: US Government Printing Office; 2010.

- 23.Patient-centered Primary Care Collaborative. Joint principles of patient centered medical home. 2007; http://www.pcpcc.net/joint-principles. Accessed March 16, 2012.

- 24.Assurance NCQF. Patient centered medical home. 2012; http://www.ncqa.org/tabid/631/default.aspx. Accessed March 16, 2012.

- 25.AHRQ. Patient Centered Medical Home: Resource Center. 2012; http://www.pcmh.ahrq.gov/portal/server.pt/community/pcmh_home/1483. Accessed March 16, 2012.

- 26.Veterans Administration. Patient-Centered Medical Home Concept Paper. 2011; www.va.gov/PrimaryCare/docs/pcmh_ConceptPaper.doc. Accessed March 16, 2012.

- 27.Han P, Rayson D. The coordination of primary and oncology specialty care at the end of life. JNCI. 2011;40:31–37. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgq003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patton MQ. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Patton MQ. Enhancing the quality and credibility of qualitative analysis. Health Services Research. 1999;34(5 Pt 2):1189–1208. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sobo EJ.Culture and Meaning in Health Services Research: a practical field guide. Walnut Creek, CA.: Left Coast Press; 2009.

- 31.Sandelowski M, Barroso J. Writing the proposal for a qualitative research methodology project. Qual Health Res. 2003;13(6):781–820. doi: 10.1177/1049732303013006003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miles MB, Huberman M. Focusing and bounding the collection of data: the substantive start. Qualitatvie Data Analysis, 2nd edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994.

- 33.Robinson L, Stacy R. Palliative care in the community: setting practice guidelines for primary care teams. Br J Gen Pract. 1994;44(387):461–464. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aspinal F, Hughes R, Dunckley M, Addington-Hall J. What is important to measure in the last months and weeks of life?: A modified nominal group study. I J Nurs Stud. 2006;43(4):393–403. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Groot MM, Vernooij-Dassen MJ, Crul BJ, Grol RP. General practitioners (GPs) and palliative care: perceived tasks and barriers in daily practice. Palliat Med. 2005;19(2):111–118. doi: 10.1191/0269216305pm937oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Borgsteede SD, Graafland-Riedstra C, Deliens L, et al. Good end-of-life care according to patients and their GPs. Br J Gen Pract. 2006;56(522):20–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Forrest CB, Glade GB, Baker AE, Bocian A, von Schrader S, Starfield B. Coordination of specialty referrals and physician satisfaction with referral care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154(5):499–506. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Gandhi TK, Sittig DF, Franklin M. al. E. Communication breakdown in the outpatient referral process. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(9):626–631. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.91119.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tarrant C, Dixon-Woods M, Colman AM, Stokes T. Continuity and trust in primary care: a qualitative study informed by game theory. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(5):440–446. doi: 10.1370/afm.1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rodriguez HP, Rogers WH, Marshall RE, Safran DG. The effects of primary care physician visit continuity on patients' experiences with care. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(6):787–793. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0182-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nutting PA, Crabtree BF, Miller WL, et al. Journey to the patient-centered medical home: a qualitative analysis of the experiences of practices in the National Demonstration Project. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8 Suppl 1:S45-56; S92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Christakis NA, Lamont EB. Extent and determinants of error in doctors' prognoses in terminally ill patients: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2000;320(7233):469–472. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7233.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tulsky JA, Fischer GS, Rose MR, Arnold RM. Opening the black box: how do physicians communicate about advance directives? Ann Intern Med. 1998;129(6):441–449. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-129-6-199809150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bradley EH, Cramer LD, Bogardus ST, Jr, Kasl SV, Johnson-Hurzeler R, Horwitz SM. Physicians' ratings of their knowledge, attitudes, and end-of-life-care practices. Acad Med. 2002;77(4):305–311. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200204000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix (DOC 39 kb)