Abstract

Remission is key to prevent progression of rheumatoid arthritis, but it is still rarely seen in clinical practice, not to speak of sustained remission, which is the best possible disease outcome of rheumatoid arthritis. New strategies and recommendations focus on achievement of remission, but it is unclear how long remission can actually be maintained in clinical practice. A study by Prince and colleagues gives insights into this question, and raises some other questions for the future.

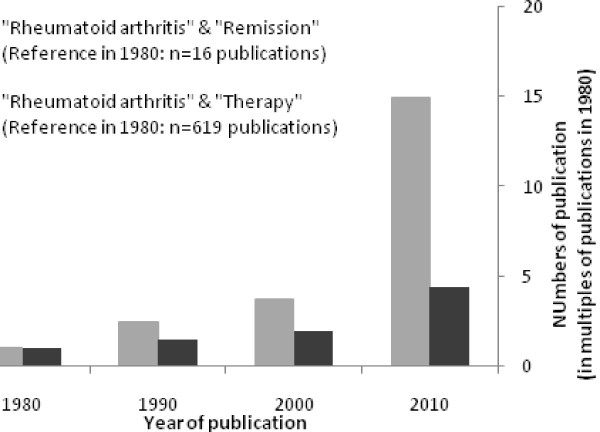

Remission of rheumatoid arthritis (RA): not so long ago this concept was illusory and far out of reach for rheumatologists. In fact, there was also little scientific interest, as the main focus of RA therapy was to prevent severe disability, which was evident in a good portion of patients until even the 1990s. It can easily be appreciated that things have changed by looking at the trend over time in the scientific interest in remission of RA: if one simply pulls publications on 'rheumatoid arthritis' and compares those including the term 'remission' with those including the term 'therapy', it is striking that when comparing the number of publications in the year 1980 with the respective number in 2010, the indexed articles increased 4.4-fold when the term 'therapy' was used, and 15-fold with the term 'remission' (Figure 1). The current article on sustainment of remission by Prince and colleagues [1] thus hits a very timely topic.

Figure 1.

Studies on remission in rheumatoid arthritis. The graph shows the disproportional increase of studies on remission of rheumatoid arthritis (light bars) when compared to studies of treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (dark bars) over the years.

In recent years, particularly the treat to target concept has engaged therapy towards reaching the goal of remission in patients with RA [2], and this has also been reflected in recent management recommendations for RA by the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) [3], and finally culminated in the publication of new remission criteria by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and EULAR [4]. Throughout the years, a central question in the definition of remission has been whether it should be at a single point in time or should include a time perspective. The most recent decision on this in the aforementioned ACR/EULAR remission criteria was the former.

This single time point definition of remission may sound contradictory to the concept of RA being a progressive and destructive disease, and disease activity over time being the most robust predictor of such progression. On a closer look, and considering the treat to target approach, it begins to make more sense: as long as remission at a single point in time is not reached, treatment needs to be adapted. There is no doubt, however, that achieving remission is just the beginning of therapeutic success in RA: years ago, for example, in their definition of remission, the US Food and Drug Administration had adopted the concept of reaching a good state without radiographic progression [5], and this concept can similarly be found in some of the most recent clinical trials.

Still, little definite is known about how often sustained remission can be achieved, and what then the minimum time requirements would be. The current paper by Prince and colleagues provides insights into the question of maintenance of remission, troubling insights in fact, as they conclude that only about half of individuals in remission at a single time point (by any instrument) remain in remission at a subsequent measurement a year later. Among those losing the remission status, only one in four patients was able to regain the remission status subsequently.

Another aspect of the data, as can be deduced from the Kaplan-Meier plots in the pulication of Prince and colleagues [1], is the fact that the greatest loss of remission status occurred after a single remission visit, and once remission was seen on two subsequent visits, the chance of remaining in remission became much higher. This matches other reports on the fact that frequency of remission in patients in a typical outpatient setting drops from approximately 40% if a single random visit is looked at to about 20% if two subsequent visits in remission are required [6]. Van der Kooij and colleagues [7] used the data from the BeST trial and further showed that the longer and the better a good clinical state is maintained, the greater the likelihood of remaining in that state.

One limitation in the present study remains the fact that the remission status has been determined only on an annual basis. RA is a fluctuating disease, and the fluctuating disease activity over time, even when overall levels were low, had been shown to be a risk factor for radiographic progression, the prevention of which is a core structural target of RA treatment [8]. Since no data are available about the time points between the annual assessments, nor radiographic data, not all the final questions can be answered by Prince and colleagues.

In fact, there are many other questions around this topic, some of which may even sound a bit heretical, such as: 'Why remission?' Particularly when biological drugs are used, reaching remission may not always be necessary: it has been shown for tumour necrosis factor-α inhibitors that structural progression is abrogated even if some levels of disease activity remain [9,10]. Recently, this has also been shown for interleukin-6 receptor blockade [11] and it remains to be seen if this is the case also for other biologic modes of action, such as inhibition of co-stimulation or B-cell-directed therapy. This supports the single point in time approach to remission as discussed above, which for some patients in some circumstances may even only need to be low disease activity [3].

In summary, we can conclude that we have come a long way, and the road remains ahead of us. Sustained remission is an ambitious goal for patients with RA, and with the current article we have learned that it is only infrequently seen. At the same time we have also noticed the developments in therapies and therapeutic strategies in the past decades, and extrapolating this to the future, it may be more than timely to start thinking about sustainment of remission, its definition as an outcome measure of successful treatment, and eventually also its definition in regards to the right timing of a therapeutic withdrawal.

Abbreviations

ACR: American College of Rheumatology; EULAR: European League Against Rheumatism; RA: rheumatoid arthritis.

Competing interests

The author declares that they have no competing interests.

See related research by Prince et al., http://arthritis-research.com/content/14/2/R68

References

- Prince FH, Bykerk VP, Shadick NA, Lu B, Cui J, Frits M, Iannaccone CK, Weinblatt ME, Solomon DH. Sustained rheumatoid arthritis remission is uncommon in clinical practice. Arthritis Res Ther. 2012;14:R68. doi: 10.1186/ar3785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Bijlsma JW, Breedveld FC, Boumpas D, Burmester G, Combe B, Cutolo M, de Wit M, Dougados M, Emery P, Gibofsky A, Gomez-Reino JJ, Haraoui B, Kalden J, Keystone EC, Kvien TK, McInnes I, Martin-Mola E, Montecucco C, Schoels M, van der Heijde D. T2T Expert Committee. Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:631–637. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.123919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smolen JS, Landewé R, Breedveld FC, Dougados M, Emery P, Gaujoux-Viala C, Gorter S, Knevel R, Nam J, Schoels M, Aletaha D, Buch M, Gossec L, Huizinga T, Bijlsma JW, Burmester G, Combe B, Cutolo M, Gabay C, Gomez-Reino J, Kouloumas M, Kvien TK, Martin-Mola E, McInnes I, Pavelka K, van Riel P, Scholte M, Scott DL, Sokka T, Valesini G. et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:964–975. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.126532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felson DT, Smolen JS, Wells G, Zhang B, van Tuyl LH, Funovits J, Aletaha D, Allaart CF, Bathon J, Bombardieri S, Brooks P, Brown A, Matucci-Cerinic M, Choi H, Combe B, de Wit M, Dougados M, Emery P, Furst D, Gomez-Reino J, Hawker G, Keystone E, Khanna D, Kirwan J, Kvien TK, Landewé R, Listing J, Michaud K, Martin-Mola E, Montie P. et al. American college of rheumatology/european league against rheumatism provisional definition of remission in rheumatoid arthritis for clinical trials. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:404–413. doi: 10.1136/ard.2011.149765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry. Clinical Development Programs for Drugs, Devices and Biological Products for the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) US Department of Health and Human Services, FDA; 1999. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/ucm071579.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Mierau M, Schoels M, Gonda G, Fuchs J, Aletaha D, Smolen JS. Assessing remission in clinical practice. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46:975–979. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Kooij SM, Goekoop-Ruiterman YP, de Vries-Bouwstra JK, Peeters AJ, van Krugten MV, Breedveld FC, Dijkmans BA, Allaart CF. Probability of continued low disease activity in patients with recent onset rheumatoid arthritis treated according to the disease activity score. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:266–269. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.079368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsing PM, Landewé RB, van Riel PL, Boers M, van Gestel AM, van der Linden S, Swinkels HL, van der Heijde DM. The relationship between disease activity and radiologic progression in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a longitudinal analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:2082–2093. doi: 10.1002/art.20350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smolen JS, Han C, van der Heijde DM, Emery P, Bathon JM, Keystone E, Maini RN, Kalden JR, Aletaha D, Baker D, Han J, Bala M, St Clair; EW. Active-Controlled Study of Patients Receiving Infl iximab for the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis of Early Onset (ASPIRE) Study Group. Radiographic changes in rheumatoid arthritis patients attaining different disease activity states with methotrexate monotherapy and infliximab plus methotrexate: the impacts of remission and tumour necrosis factor blockade. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:823–827. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.090019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landewe R, van der HD, Klareskog L, van VR, Fatenejad S. Disconnect between inflammation and joint destruction after treatment with etanercept plus methotrexate: results from the trial of etanercept and methotrexate with radiographic and patient outcomes. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:3119–3125. doi: 10.1002/art.22143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smolen JS, Avila JC, Aletaha D. Tocilizumab inhibits progression of joint damage in rheumatoid arthritis irrespective of its anti-inflammatory effects: disassociation of the link between inflammation and destruction. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;71:687–693. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]