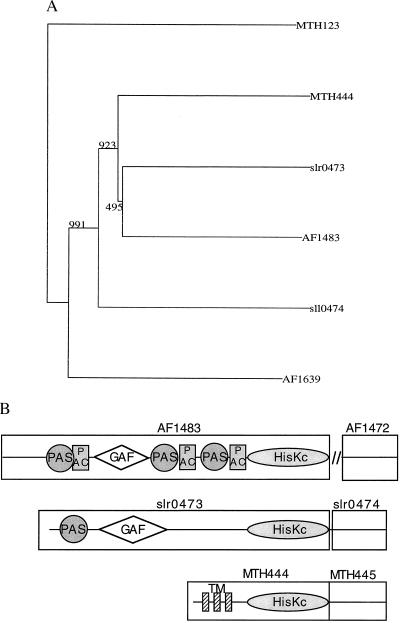

Figure 1.

An example of complexities in assigning orthology to multidomain proteins. The M. thermoautotrophicum genes MTH444 (a sensory transduction histidine kinase) and MTH445 (a sensory transduction regulatory protein) are orthologs of the Synechocystis sequences slr0473 (phytochrome; ref. 41) and slr0474, respectively (the gene nomenclature is from the GenBank files of complete genomes, the first letters of gene names generally represent the initials of the genomes). The arguments for orthology are: (i) The genes have a 34.8% and a 40.2% identity to each other, which is significantly higher than either of them has to other sequences in the other’s genome. (ii) They are neighboring genes in both genomes. (iii) Both MTH444 and slr0473 have the highest level of identity to a single sequence from a third species Archeoglobus fulgidus (42), AF1483, the same is true for MTH445 and slr0474 with respect to AF1472. Interestingly, the level of identity of the Synechocystis sequences slr0473 and slr0474 is significantly higher to the M. thermoautotrophicum and A. fulgidus sequences than it is to any of the sequences in the Bacteria, including sequences in Synechocystis itself. The reverse is even more dramatic: MTH445, AF1472, and MTH444, AF1483 are more identical, not only to their Synechocystis orthologs, but also to 27 respectively 28 other sequences in Synechocystis than they are to sequences in their own genomes. These 27 (28) sequences are paralogs of slr0473 (slr0474). The similarity between MTH444 and AF1483 is slightly lower than that between AF1483 and slr0473, whereas the similarity between AF1472 and MTH444 is significantly higher than that of either of them to slr0473. Neighbor-joining clusterings of the histidine kinase orthologs together with their most similar sequences from the three genomes (A) illustrates the most likely evolutionary scenario: a horizontal transfer of the genes in the branch that has led to Synechocystis, to the branch leading to M. thermoautotrophicum and A. fulgidus. Given the relative similarities of the proteins, this event occurred after a major amplification of the histidine kinase family in Synechocystis and not long before the split of the branches that led to M. thermoautotrophicum and A. fulgidus. The fact that none of the proteins have a detectable homolog in M. jannaschii, which branched off in the Archaea not long before the branching of A. fulgidus and M. thermoautotrophicum, supports this hypothesis. The only inconsistency is the fact that in the clustering of the kinases, AF1483 and slr0473 are slightly more similar to each other than either is to MTH444. (B) Domain architecture of slr0473, AF1483, and MTH444. The genes slr0473 and AF1483 are multidomain proteins, carrying GAF (43) domains and PAS (44, 45) motifs at their N terminus. The PAC motif (44, 45) could be detected only in AF1483. The GAF domain and PAS and PAC motifs are absent in MTH444, and have been replaced by three transmembrane regions (see ref. 11). All three genes possess a histidine kinase domain (HisKc) at their C terminus; 3′ to the slr0473 and MTH444 genes are the regulatory response genes slr0474 and MTH445. The distances between the reading frames are short: 15 nucleotides in Synechocystis and the reading frames overlap in M. thermoautotrophicum. In A. fulgidus the spatial association between these genes is absent. The absence of the GAF and PAS domains in MTH444 might have caused different selective constraints in MTH444 than in slr0473 and AF1483, and thus increased its rate of evolution, thereby reducing its similarity to its A. fulgidus and Synechocystis orthologs at a relatively high rate. The GAF, PAC, and PAS domains were predicted by using the smart system (ref. 46; http://www.bork.embl-heidelberg.de/Modules/sinput.shtml).