Abstract

Purpose: To assess if the uterine cavity depth measured by a blind pre-cycle mock transfer changes after gonadotropin stimulation.

Methods: This is a retrospective cohort study at an academic IVF program involving 128 infertility patients. The main outcome measures were uterine cavity depth measured at the blind pre-stimulation mock transfer and the ultrasound-guided embryo transfer.

Results: A ≥ 1 cm increase in uterine cavity depth was found in 57.9% of the patients. The mean pre-cycle blind mock transfer uterine depth significantly differed from the mean uterine depth measured at embryo transfer. Based on the mock transfer, the anticipated embryo transfer depth was significantly less than the actual ultrasound-guided embryo transfer depth.

Conclusion: Uterine depth significantly differed between the blind pre-cycle mock transfer measurement and the ultrasound-guided embryo transfer measurement. The mock transfer may predict a difficult embryo transfer but it is an inaccurate predictor of the final embryo transfer depth.

Keywords: Blind pre-cycle mock embryo transfer, In vitro fertilization, Infertility, Pregnancy rate, Ultrasound-guided embryo transfer, Uterine cavity depth

Introduction

There are many factors that determine a successful outcome during an in vitro fertilization (IVF) cycle. A successful embryo transfer is the final step of the IVF process. To ensure proper placement of the embryos, many providers perform a transabdominal ultrasound-guided embryo transfer (UG-ET). The UG-ET technique has been the focus in many clinical trials and two large meta-analyses [1–11].

The technique of UG-ET was first described by Strickler et al. and Leong et al. and has been met with great advances in ultrasound technology and greatly expanded clinical experience [12, 13]. The use of ultrasound to place the embryos in the uterine cavity has been shown to improve pregnancy outcome in multiple studies [1–4]. Two recent meta-analyses have confirmed the improvement in pregnancy success with UG-ET [5, 6].

Often providers will perform a pre-cycle mock transfer and uterine cavity measurement to document the depth of the uterus, the path of the cervical canal, and the degree of difficulty in entering the uterine cavity. The depth of the uterus with the pre-cycle mock transfer can then be used as a template for the depth of the planned embryo transfer. According to provider preference, embryos are generally placed 1–2 cm from the uterine fundus. The depth of embryo placement has been shown to influence IVF pregnancy success [7–10].

The published clinical trials on UG-ET have shown conflicting results. In the eight prospective clinical trials reviewed by Buckett et al. and Sallam et al. five showed a benefit of UG-ET and only three of these studies were deemed by the reviewing authors as properly randomized [5, 6]. Most recently, Shamonki et al. presented the results of a small prospective study suggesting that a benefit does exist with UG-ET [11]. This trial concluded that even in highly experienced clinical hands UG-ET provided a major benefit over the traditional blind transfer.

The conflicting results found in our literature review prompted us to examine the uterine depth measured at the time of UG-ET compared to the anticipated transfer depth determined by the blind pre-cycle mock transfer. We hypothesized that using the blind pre-cycle mock transfer uterine depth was an inaccurate measurement of actual uterine depth at the time of embryo transfer. We planned a retrospective study to assess if the pre-cycle mock transfer measurement of uterine depth changed after gonadotropin stimulation and to evaluate the parameters that were associated with any change in uterine depth.

Materials and methods

Population

The patient population consisted of 128 couples undergoing 128 fresh autologous IVF cycles. All infertile women undergoing IVF were eligible to participate in the study. Inclusion criteria included normal basal FSH concentration per our laboratory (≤12 mIU/mL), documented measurement of the blind pre-cycle mock transfer uterine depth, and transabdominal ultrasound documented uterine depth at the time of the embryo transfer. Patients were included independent of their diagnoses or reproductive history. Exclusion criteria included patients >42 years and patients without a documented cavity depth for both the pre-cycle mock transfer and UG-ET.

Experimental design

This is a retrospective cohort analysis of 128 couples undergoing 128 IVF cycles at the Tripler Army Medical Center In Vitro Fertilization Institute from January 2002 to September 2005. IRB approval was obtained from the Tripler Army Medical Center Institutional Review Board, Honolulu, HI.

To document uterine cavity depth, degree of transfer difficulty, and anticipated embryo transfer depth, the patients received a blind pre-cycle mock transfer using a Wallace trial transfer catheter (Cooper Surgical, Shelton, CT) while on oral contraceptive pills (OCs) in the month prior to undergoing gonadotropin stimulation. The mock embryo transfer was preformed as a blind technique with the depth of the uterine cavity determined by clinical touch not by ultrasound visualization. The trial transfer catheter was placed through the cervix until the tip was perceived to touch the uterine fundus. This depth was measured with the anticipated embryo transfer to occur at a depth 1.5 cm short of the fundus. All embryo transfers were performed with ultrasound guidance using a 5 MHz transducer (Aloka SSD-3500, Aloka, Wallingford, CT). The depth of the embryo transfer and the uterine depth were recorded. All patients had a full bladder prior to both the mock transfer and the embryo transfer. All mock transfers and embryo transfers were performed by the senior author (JLF).

All patients started OCs (30 μg ethinyl estradiol, 0.15 mg norgestrel) the evening of menstrual day 3. The patients continued the OCs for 21 days prior to pituitary suppression with GnRH agonist (500 μg) (GnRH-a, Luprolide acetate, Lupron; TAP Pharmaceuticals, North Chicago, IL, USA). There was a seven day overlap between the OCs and the GnRH-a. After 14 days of GnRH-a (500 μg), the dose was decreased to 250 μg and stimulation with exogenous gonadotropins was initiated 5 days later. When the largest cohort of follicles reached the 16 mm to 18 mm range, a single 10,000 IU intramuscular dose of hCG was administered. Transvaginal follicular aspiration was performed approximately 35 hr after hCG administration. Using a Wallace transfer catheter (Cooper Surgical, Shelton, CT), embryos were transferred 1.5 cm from the uterine cavity apex under transabdominal ultrasound guidance 72–120 hr after follicular aspiration.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measure was the change in uterine depth from the blind mock embryo transfer to the UG-ET. Secondary outcome measures were age, BMI, day 3 hormone levels (FSH, LH, estradiol), IVF stimulation parameters (antral follicles, ovarian volume, peak estradiol on day of hCG administration, number of follicles, number of oocytes, number of embryos, number of ampules of gonadotropins used, and days of stimulation) and pregnancy outcomes (implantation rate, pregnancy rate, miscarriage rate, and live birth rate).

Pregnancies and the accompanying rates were defined as follows. Initial pregnancy was documented by a rising serum β-hCG concentration on luteal days 14 and 16. Biochemical pregnancies were defined as having a positive pregnancy test on luteal day 14 with a rising titer confirmed by a second β-hCG concentration but with loss of the pregnancy prior to sonographic evidence of the pregnancy. Spontaneous pregnancy loss was defined as a pregnancy loss following sonographic visualization of an intrauterine gestational sac at five to six weeks of gestation. Live birth rate was defined as those pregnancies proceeding to deliver a live infant. Implantation rate was calculated by dividing the number of gestational sacs visualized on transvaginal ultrasound at five to six weeks gestation by the number of embryos transferred.

Statistical analysis

Approximately 130 patients were required to detect a 20% difference in uterine cavity depth with a power of 0.8 and an α-error of 0.05. A Wilcoxon Signed Rank test was used to compare uterine cavity depth and other outcome variables not normally distributed in the same patient. A Mann-Whitney Rank Sum test was used to compare uterine cavity depth and other outcome variables not normally distributed between two different groups. For normally distributed data, a paired t-test was used to compare uterine depth measurements in the same patient. A t-test was used to compare normally distributed data between two different groups.

The amount of uterine cavity depth change was evaluated for each patient. Success rates (implantation rates, pregnancy rates, pregnancy loss rates, and live birth rates) were calculated for each 0.5 cm uterine depth change from 0.0 cm to 3.0 cm. The success rates above and below each 0.5 cm increment change in uterine depth were evaluated to determine if there were any obvious break points at which there was a significant change in success rates. Contingency table analysis and receiver-operator characteristic (ROC) curves were then used to evaluate the outcome rates above and below the selected threshold value. Differences in outcome rates were analyzed using a Chi-square or two-tailed Fisher exact test where appropriate.

Univariate analysis included regression and correlation coefficients examining the association of endometrial depth measurements with parameters of ovarian reserve and response. An alpha error of 0.05 was considered significant for all comparisons. Relative risk and 95% confidence intervals are displayed where appropriate. All data are reported as means with their associated standard deviations.

Results

A total of 128 IVF cycles were analyzed. The patient demographics, pre-stimulation and stimulation parameters are depicted in Table 1. Of the 128 patients, 70 (54.7%) became pregnant, 11 (15.7%) had a pregnancy loss, and 59 (46.1%) had a live birth. The implantation rate for the patient population was 28.9%. When subdividing the patients into those who conceived (n = 70) and those who did not conceive (n = 58), there were expected significant differences between these two groups with regard to age, peak estradiol level on day of hCG administration, number of follicles, number of oocytes obtained, total number of embryos, ampules of gonadotropins used, and number of days of stimulation (Table 1). However, there was no difference in the blind pre-cycle mock transfer uterine cavity depth or the UG-ET uterine cavity depth when comparing the pregnant to the non-pregnant patients (Table 1).

Table 1.

Population demographics, pre-stimulation and stimulation parameters for the IVF study group which was further subdivided into patients who conceived and patients who did not conceive

| Variables | All patients (N = 128) | Pregnant (N = 70) | Not Pregnant (N = 58) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 33.8 ± 4.3 | 33.3 ± 3.9 | 34.7 ± 4.9 | <0.05b |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.8 ± 4.9 | 25.7 ± 4.8 | 25.6 ± 5.0 | 0.84b |

| Day 3 FSH (mIU/mL) | 5.5 ± 1.6 | 5.4 ± 1.7 | 5.6 ± 1.4 | 0.26c |

| Day 3 LH (mIU/mL) | 5.3 ± 3.4 | 5.1 ± 2.9 | 5.5 ± 4.2 | 0.71b |

| Mock uterine depth (cm) | 7.6 ± 0.7 | 7.6 ± 0.8 | 7.4 ± 0.7 | 0.83b |

| UG-ET uterine depth (cm) | 8.4 ± 0.7 | 8.5 ± 0.8 | 8.3 ± 0.5 | 0.67b |

| Total ovarian volume (cm3) | 13.5 ± 6.6 | 14.4 ± 6.6 | 12.3 ± 6.8 | 0.24c |

| Total antral follicles | 20.3 ± 13.1 | 23.2 ± 13.8 | 17.3 ± 11.3 | 0.11b |

| Day of hCG estradiol (pg/mL) | 2559.5 ± 1497.8 | 2718.8 ± 1458.4 | 2351.7 ± 1540.0 | <0.05b |

| Number of follicles | 18.1 ± 11.0 | 19.2 ± 10.8 | 16.6 ± 11.0 | <0.05b |

| Number of oocytes retrieved | 15.9 ± 11.2 | 17.5 ± 11.9 | 14.9 ± 11.5 | <0.05b |

| Number of embryos | 10.0 ± 7.6 | 11.5 ± 8.0 | 8.9 ± 7.5 | <0.01b |

| Ampules of gonadotropins used | 49.6 ± 19.6 | 46.6 ± 19.8 | 51.1 ± 21.3 | <0.05b |

| Days of stimulation | 9.5 ± 2.0 | 9.2 ± 2.0 | 9.8 ± 2.1 | <0.05b |

Note. Values represent means and the associated standard deviation.

aComparing pregnant patients with those not pregnant, p < 0.05 is considered statistically significant.

bNormality test failed. Mann-Whitney Rank Sum Test was used to determine significance.

cNormality test passed. T-Test was used to determine significance.

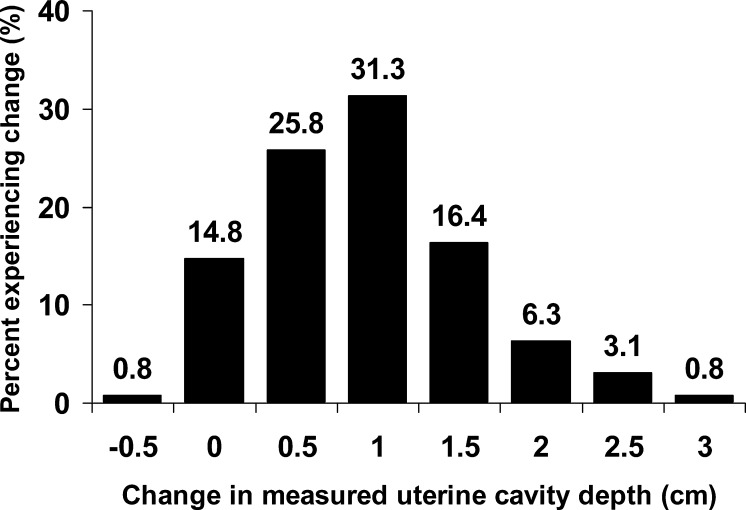

The percent of patients experiencing a change in uterine cavity depth is depicted in Fig. 1. Only one patient had a measured decrease in uterine depth (−0.5 cm), while 14.8% experienced no changed in uterine depth. One patient had a 3 cm increase in measured uterine depth and 57.9% of the patients had a ≥1 cm increase in uterine depth (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Histogram depicting the percent of the patient population experiencing each 0.5 cm change in measured uterine cavity depth. The change in uterine cavity depth is defined as the change in the measured depth from the blind pre-cycle mock transfer to the ultrasound guided embryo transfer

The mean blind pre-cycle mock embryo transfer uterine depth measurement was 7.6 ± 0.7 cm (Table 1). The mean UG-ET uterine depth was 8.4 ± 0.7 cm. The mean change in uterine cavity depth measurement for the patient population was 0.94 ± 0.7. Using a Wilcoxon Signed Rank test, the difference in uterine depth was significant (p < 0.001). Based on the blind pre-cycle mock transfer uterine depth, the anticipated embryo transfer depth (6.1 ± 0.7) was significantly different than the actual ultrasound-guided embryo transfer depth (6.9 ± 0.7 cm) (p < 0.001).

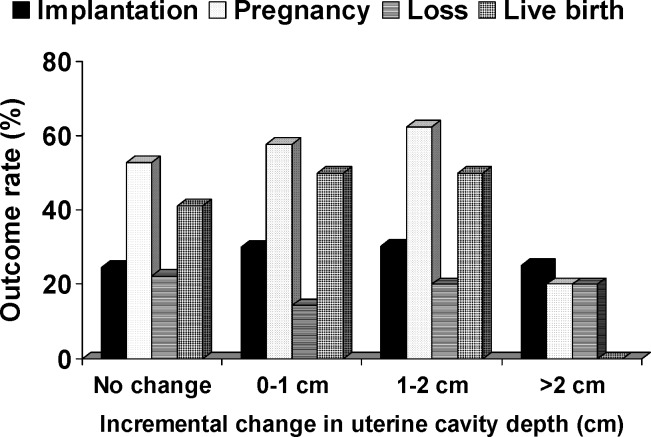

When evaluating pregnancy outcomes (implantation rate (IR), pregnancy rate (PR), miscarriage rate (SAB), and live birth rate (LBR)), there was no significant difference in the pre-cycle blind mock transfer uterine depth (IR: p = 0.72, PR: p = 0.83, SAB: p = 0.65, LBR: p = 0.90), UG-ET uterine depth (IR: p = 0.77, PR: p = 0.67, SAB: p = 0.69, LBR: p = 0.89), or change in uterine depth (IR: p = 0.83, PR: p = 0.67, SAB: p = 0.78, LBR: p = 0.95). Figure 2 depicts the success rates for the various changes in uterine depth. There was no significant difference in success rates based on amount of uterine cavity depth change. While the success rates for the >2 cm incremental change group appear lower, this group was represented by only 5 patients and therefore grossly underpowered to show a significant difference. Contigency table analysis evaluating uterine depth change at intervals of 0.5 cm did not find a significant threshold value at any uterine depth increment change for any of the IVF outcomes.

Fig. 2.

Outcome rates (implantation, pregnancy, loss, and live birth) for the patient population subdivided into 1.0 cm incremental uterine cavity depth changes. The change in uterine cavity depth is defined as the change in the measured depth from the blind pre-cycle mock transfer to the ultrasound guided embryo transfer

When evaluating the change from blind pre-cycle mock transfer uterine depth to the UG-ET uterine depth, univariate analysis did not reveal a significant correlation with any of the IVF pre-stimulation or stimulation parameters (age, BMI, day 3 hormone levels (FSH, LH, estradiol), antral follicles, ovarian volume, peak estradiol, follicles, oocytes, embryos, number of ampules of gonadotropins used, and days of stimulation) (data not shown).

Discussion

Our study suggests that the depth of the uterine cavity increased during IVF stimulation by an average of almost 1 cm (0.94 ± 0.7 cm). If the blind embryo transfer technique is used based on a pre-cycle blind mock transfer, these data suggest that the embryo transfer is unlikely to occur at the planned uterine cavity depth. These findings are significant since the depth of embryo placement has been shown to influence IVF pregnancy success [7–10]. Our results agree with the three recent studies which suggested that a discrepancy may exist between the pre-cycle and the in-cycle uterine depth [10, 11, 14].

Knowledge of the uterine cavity depth is crucial at the time of embryo transfer. If the pre-cycle measured uterine cavity depth is not accurate and not realized at the time of embryo transfer, the success of the IVF cycle can be jeopardized. Not all providers use a transabdominal ultrasound to guide the embryo transfer. Some providers use the pre-cycle uterine cavity measurement to determine the depth of embryo placement and perform a blind (clinical touch) embryo transfer. Furthermore, in obese patients and patients with a retroverted uterus, it may be difficult to adequately visualize the uterus and embryo placement with a transabdominal ultrasound at the time of embryo transfer. In these cases, the pre-cycle uterine cavity measurement is used to determine depth of embryo placement. Additionally, a recent study looked at the consistency in uterine position between the mock and the real embryo transfer and found that a retroverted uterus at the time of a mock transfer will often change position at the real transfer [15].

Our data suggest that without the use of UG-ET, the embryos will be transferred on average 1 cm lower in the uterine cavity than anticipated. Buckett et al. concluded that the main disadvantage of UG-ET stems from the additional time and personnel required for this type of embryo transfer [5]. It has been postulated by recent investigators that the benefit of UG-ET is derived from its ability to minimize several important factors [1–8]. These factors include the improper placement of embryos within the uterine cavity, placement of embryos completely outside the uterine cavity, or indentation of the endometrium [9, 16, 17]. Others have suggested that difficult transfers leading to more pronounced cervical trauma, endometrial trauma, or bleeding are potential variables [1–5].

Although we did not find a significant correlation between estradiol levels and uterine depth change, hormonal stimulation to the uterus has been shown to produce a change the uterine depth [18]. In addition, the mock transfer was performed after 21 days of pituitary suppression. Pituitary suppression may decrease uterine cavity depth by decreasing uterine size. Another possible reason for the inaccuracy of the measurement is that the pre-cycle mock transfer was performed as a blind (clinical touch) technique. The blind technique has been shown to be less accurate than the ultrasound guided technique [11].

Since transfer depth in relationship to the uterine fundus is an important factor during an embryo transfer, transferring embryos under direct ultrasound guidance allows a more accurate transfer at the desired uterine depth. Only one patient experienced a decrease in uterine cavity depth with gonadotropin stimulation. This highlights the fact that when using the blind pre-cycle mock transfer uterine depth measurement to determine embryo transfer depth the embryo transfer catheter is unlikely to contact the uterine fundus and embryos are more likely to be placed lower in the uterine cavity than planned.

Although there were numerous significant differences between the pregnant and non-pregnant patients, these data do not reflect a change in success rates based on incremental uterine depth change (Table 1). However, all embryo transfers were performed under ultrasound guidance. This change in uterine depth may be a factor in the decreased pregnancy and implantation rates seen when UG-ET is compared to the clinical touch method [1–6].

Possible weaknesses of this study include its retrospective nature. However, these data were derived from a prospective database. Therefore, there was no chart review and no patients were lost to follow-up. This decreases the possibility of selection and information biases. The use of contingency table analysis and ROC curves to seek significant threshold values so as not to use arbitrary cut-off points was a major strength of the study. Likewise, all stimulation cycles, ultrasounds, oocyte retrievals, and embryo transfers were performed by the senior author (JLF).

Conclusion

In summary, these data demonstrate a significant change in uterine cavity depth measurements from the blind pre-cycle mock transfer to the UG-ET. The exact etiology for the change in uterine depth is uncertain. The blind pre-cycle mock transfer may still be useful for assessing the possibility of a difficult embryo transfer. However, based on these data, the utility for determining embryo transfer uterine depth with the blind pre-cycle mock transfer is questionable. More research is needed to ascertain the utility of a pre-cycle ultrasound-guided mock transfer in determining the ultimate uterine depth for the embryo transfer.

Acknowledgments

There was no financial support for this study. This study was approved by the Department of Clinical Investigation at Tripler Army Medical Center, Honolulu, HI. The views expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or the U. S. Government.

References

- 1.Wood EG, Batzer FR, Go KJ, Gutmann JN, Corson SL. Ultrasound-guided soft catheter embryo transfers will improve pregnancy rates in in-vitro fertilization. Hum Reprod. 2000;15:107–112. doi: 10.1093/humrep/15.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Letterie GS. Three-dimensional ultrasound-guided embryo transfer: a preliminary study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:1983–1987. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.02.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tang OS, Ng EH, So WW, Ho PC. Ultrasound-guided embryo transfer: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Hum Reprod. 2001;16:2310–2315. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.11.2310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li R, Lu L, Hao G, Zhong K, Cai Z, Wang W. Abdominal ultrasound-guided embryo transfer improves clinical pregnancy rates after in vitro fertilization: experiences from 330 clinical investigations. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2005;22:3–8. doi: 10.1007/s10815-005-0813-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buckett VM. A meta-analysis of ultrasound-guided versus clinical touch embryo transfer. Fertil Steril. 2003;80:1037–1041. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(03)01015-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sallam HN, Sadek SS. Ultrasound-guided embryo transfer: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Fertil Steril. 2003;80:1042–106. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(03)01009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Egbase PE, Al-Sharhan M, Grudzinskas JG. Influence of position and length of uterus on implantation and clinical pregnancy rates in IVF and embryo transfer treatment cycles. Hum Reprod. 2000;15:1943–1946. doi: 10.1093/humrep/15.9.1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frankfurter D, Silva CP, Mota F, Trimarchi JB, Keefe DL. The transfer point is a novel measure of embryo placement. Fertil Steril. 2003;79:1416–1421.. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(03)00263-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coroleu B, Barri Pn, Carreras O, Martinez F, Parriego M, Hereter L, Parera N, Veiga A, Balasch J. The influence of the depth of embryo replacement into the uterine cavity on implantation rates after IVF: a controlled, ultrasound-guided study. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:341–346. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.2.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pope CS, Cook EK, Arny M, Novak A, Grow DR. Influence of embryo transfer depth on in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer outcomes. Fertil Steril. 2004;81:51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shamonki MI, Spandorfer DS, Rosenwaks Z. Ultrasound-guided embryo transfer and the accuracy of trial embryo transfer. Hum Reprod. 2005;20:709–716. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strickler RC, Christianson C, Crane JP, Curato A, Knight AB, Yang V. Ultrasound guidance for human embryo transfer. Fertil Steril. 1985;43:54–61. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)48317-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leong M, Leung C, Tucker M, Wong C, Chan H. Ultrasound-assisted embryo transfer. Fertil Steril. 1986;3:383–385. doi: 10.1007/BF01133254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shamonki MI, Schattman GL, Spandorfer SD, Chung PH, Rosenwaks Z. Ultrasound-guided trial transfer may be beneficial in preparation for an IVF cycle. Hum Reprod. 2005;20:2844–2849. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dei139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henne MB, Milki AA. Uerine position at real embryo transfer compared with mock embryo transfer. Hum Reprod. 2004;19:570–572. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosenlund B, Sjoblom P, Hillensjo T. Pregnancy outcome related to the site of embryo deposition in the uterus. J Assist Reprod Genet. 1996;13:511–513. doi: 10.1007/BF02066534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Woolcott R, Stanger J. Potentially important variables identified by transvaginal ultrasound-guided embryo transfer. Hum Reprod. 1997;12:963–966. doi: 10.1093/humrep/12.5.963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gull B, Karlsson B, Milson I, Granberg S. Factors associated with endometrial thickness and uterine size in a random sample of postmenopausal women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:386–391. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.115869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]