Abstract

The lantibiotic lacticin 3147 has been the focus of much research due to its broad spectrum of activity against many microbial targets, including drug-resistant pathogens. In order to protect itself, a lacticin 3147 producer must possess a cognate immunity mechanism. Lacticin 3147 immunity is provided by an ABC transporter, LtnFE, and a dedicated immunity protein, LtnI, both of which are capable of independently providing a degree of protection. In the study described here, we carried out an in-depth investigation of LtnI structure-function relationships through the creation of a series of fusion proteins and LtnI determinants that have been the subject of random and site-directed mutagenesis. We establish that LtnI is a transmembrane protein that contains a number of individual residues and regions, such as those between amino acids 20 and 27 and amino acids 76 and 83, which are essential for LtnI function. Finally, as a consequence of the screening of a bank of 28,000 strains producing different LtnI derivatives, we identified one variant (LtnI I81V) that provides enhanced protection. To our knowledge, this is the first report of a lantibiotic immunity protein with enhanced functionality.

INTRODUCTION

Lantibiotics are posttranslationally modified antimicrobial peptides produced by Gram-positive bacteria. Many lantibiotics are active in nanomolar concentrations and have a broad spectrum of activity against many bacteria, including drug-resistant pathogens (5, 7, 18, 35, 43). As a consequence, lantibiotics have been the subject of much investigation with respect to clinical and/or food applications (3, 4, 7, 15, 30, 55). Because of the potency of lantibiotics, each producer must provide immunity against its own lantibiotic. Lacticin 3147 is a type II lantibiotic produced by rare strains of Lactococcus lactis (50). The lacticin 3147 producer employs two systems to provide immunity (12, 13, 34). One system is comprised of an ABC transporter complex designated LtnFE, thought to function through the extrusion of lacticin 3147 from the cytoplasmic membrane. Such immunity transporters have been identified in other lantibiotic producers and are generically designated LanFE(G) (17, 41, 44, 48, 49). Immunity to lacticin 3147 is also provided by a dedicated immunity protein, LtnI. Generically designated LanI, these heterogeneous proteins/lipoproteins can provide protection against an associated lantibiotic alone or in combination with LanFE(G) (27, 31, 34, 40, 42). Immunity to a number of other lantibiotics, including Pep5, epicidin 280, lactocin S, and cytolysin, is provided solely by the corresponding immunity proteins, PepI, EciI, LasI, and CylI, respectively (6, 19, 21, 47).

Relatively little regarding the mechanism by which LtnI provides protection to lacticin 3147 is known. Although this 116-amino-acid (aa) protein is predicted to be membrane associated on the basis of hydrophobicity profiling (34), to date, other insights into LtnI function have had to be inferred from what is known about other LanI proteins. NisI and SpaI, proteins associated with immunity to nisin and subtilin, respectively, differ from LtnI in that they are lipoproteins that are linked to the membrane by a lipid moiety. These proteins have been investigated in some depth. For example, a series of C-terminally truncated NisI proteins were created and expressed in L. lactis in order to identify the region of NisI that interacts with nisin. A 21-amino-acid C-terminal deletion resulted in the retention of just 14% of the protective effect provided by native NisI, whereas longer deletions (up to 74 aa) had no additional effect. When the corresponding 21-aa region of SpaI was replaced with that of NisI and expressed in L. lactis, the SpaI'-‘NisI fusion protein provided immunity to nisin, confirming the nisin-specific protective capabilities of these C-terminally located amino acids (51).

Similar investigations have been carried out to identify essential domains within PepI, a LanI protein associated with Pep5 immunity (37), and its homologue, EciI, which is responsible for epicidin 280 immunity and cross immunity to Pep5 (19). The introduction of charged amino acids into the N-terminal hydrophobic 20-amino-acid stretch of PepI impacted the membrane localization of the protein. One such mutant protein, PepI-I17R, conferred substantially reduced immunity to Pep5. The addition of an F13D change in this background slightly increased immunity levels compared to that achieved with I17R alone but also resulted in an enhanced susceptibility to proteolysis (21). To investigate the importance of the C-terminal domain of PepI, a truncated protein, PepI1-65, that lacked the four C-terminally located charged amino acids was created. The immunity provided by this truncated version was greatly reduced (42). A further study focused on three other C-terminally truncated versions of PepI: PepI1-63, PepI1-57, and PepI1-53. As each segment consisting of two positively charged residues next to one negatively charged amino acid was removed, the level of protection was further reduced. The negative impact on immunity was evident, despite the fact that these proteins remained located in the membrane, thereby suggesting that the C terminus of PepI is also involved in target recognition. The importance of charge distribution within this C-terminal region was also apparent from the negative impact on immunity arising from the creation of truncated versions of PepI (21).

Finally, the structure and function of the LanH protein associated with immunity to the type II lantibiotic nukacin ISK-1, NukH (92 amino acids), have been extensively investigated (1). NukH, although distinct from LanI proteins, in that it functions as an accessory protein to the ABC transporter immunity system NukFEG, has a transmembrane (TM) location. Through the creation of truncated versions of NukH fused to an alkaline phosphatase (PhoA) reporter and by evaluation of their sensitivity to proteinase K, it was established that NukH contains 3 transmembrane domains (TMDs). The PhoA fusion sites of NukH from amino acids 1 to 33 [NukH(1-33)-PhoA] and amino acids 1 to 92 [NukH(1-92)-PhoA] were shown to be extracellularly located, in that they were subject to proteinase K degradation, whereas the PhoA domain of NukH(1-64)-PhoA was not, thereby supporting in silico predictions that this corresponded to a transmembrane domain (40). To identify functional domains within NukH, amino acid substitutions, deletions, and truncated versions were created. Deletion of either the N terminus (positions 1 to 6) or the C terminus (positions 89 to 92) of NukH did not have any effect on its nukacin ISK-1 binding capabilities or immunity function. However, substituting the amino acids of the internal or external loop for alanines abolished NukH function. It was revealed that the external loop was of the greatest importance with respect to target binding and that while deletion of the transmembrane regions abolished immunity completely, the truncated protein was still capable of binding its target (40).

Here, to address a lack of knowledge with respect to the topology and functional domains of LtnI or, indeed, type II immunity proteins in general, a series of fusion proteins and site-directed mutagenesis derivatives was created. We also created the first bank of randomly mutated LanI proteins and identified the first LanI variant that provides enhanced lantibiotic protection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Growth conditions.

The strains and plasmids utilized during this study are found in Table 1. Lactococci were routinely grown at 30°C without aeration in M17 broth (Oxoid Ltd., Basingstoke, Hampshire, England) supplemented with 0.5% (wt/vol) glucose (GM17); GM17 supplemented with K2HPO4 (36 mM), KH2PO4 (13.2 mM), sodium citrate (1.7 mM), MgSO4 (0.4 mM), (NH4)2SO4 (6.8 mM), and 4.4% glycerol (GM17 freezing buffer) without aeration; or GM17 agar unless otherwise stated. Escherichia coli was grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth (45) at 37°C with vigorous agitation. Antibiotics were used, where indicated, at the following concentrations: ampicillin (Amp) was used at a concentration of 100 μg ml−1 for E. coli, and chloramphenicol (Cm) was used at a concentration of 10 μg ml−1 for E. coli and one of 5 μg ml−1 for L. lactis.

Table 1.

Strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli CC118 | ΔphoA20 | 32 |

| E. coli Top10 | Intermediate cloning host | Invitrogen |

| L. lactis MG1363 | Plasmid free, lacticin 3147 sensitive | 16 |

| L. lactis MG1363/pMRC01 | MG1363 with lacticin 3147-producing plasmid | 8 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pRMCD28 | E. coli phoA in pWSK29; Ampr | 11 |

| pRMCD70 | E. coli lacZ in pWSK29; Ampr | 11 |

| pNZ44 | L. lactis P44 promoter in pNZ8048; Cmr | 36 |

| pNZ44ltnI | pNZ44 containing ltnI | 12 |

General molecular biology techniques.

Plasmid DNA was isolated from E. coli strains using a High Pure plasmid isolation kit as recommended by the manufacturer (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). Plasmids isolated from L. lactis were isolated in the same way following treatment with protoplast buffer (5 mM EDTA, 50 U ml−1 mutanolysin, 10 mg ml−1 lysozyme, 0.75 M sucrose, 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5). Total cell DNA was isolated using a Roche High Pure PCR template preparation kit (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). Chemically competent E. coli Top10 was used as an immediate host for plasmid pNZ44 following the manufacturer's guidelines for transformation. L. lactis strains were made electrocompetent following the procedure described by Holo and Nes (23). In both cases, electrotransformation was performed with an Electro cell manipulator (BTX-Harvard apparatus). PCR was performed according to standard procedures using BioTaq DNA (Bioline), Vent polymerase (New England Biolabs), KOD DNA polymerase (Novagen), and Pwo DNA polymerase (Roche Diagnostics). For colony PCR, genomic DNA was accessed through lysis of cells in 10% Igepal CA-630 (Sigma-Aldrich) at 94°C for 10 min. Extraction of DNA from agarose gels were performed using a KeyPrep spin gel DNA cleanup kit (Anachem, Bedfordshire, United Kingdom) as recommended by the manufacturer. DNA ligations were executed according to established procedures using T4 ligase supplied by Roche Diagnostics. Restriction enzymes were also used according to the manufacturer's guidelines and were supplied by Roche Diagnostics. DNA sequencing was performed by MWG Biotech AG or Beckman Coulter Genomics.

Random mutagenesis of ltnI.

Plasmid DNA was isolated from E. coli Top10/pNZ44ltnI (12) using a Maxiprep plasmid kit (Qiagen) to a concentration of approximately 428 ng μl−1. pNZ44ltnI was then used as the template for the Genemorph II random mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) according to the manufacturer's guidelines. To introduce an average of 1 base pair change in the 488-bp cloned fragment, amplification was performed in a 50-μl reaction mixture containing approximately 500 ng of target DNA (pNZ44ltnI), 2.5 units Mutazyme DNA polymerase, 1 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, and 200 ng each of primers LtnIRMFor and LtnIRMrev. The reaction mixture was preheated at 96°C for 1 min, then incubated for 25 cycles at 96°C for 1 min, 52°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min, and then finished by incubation at 72°C for 10 min. Amplified products were purified by gel extraction and reamplified with KOD DNA polymerase, before being digested with KpnI and XbaI, ligated with similarly digested and shrimp alkaline phosphatase-treated pNZ44, and introduced into E. coli Top10. To determine if the correct rate of mutation had been achieved, recombinant plasmid DNA was isolated from selected clones and sequenced. Transformants were pooled and stored in 80% glycerol at −20°C. Plasmid DNA isolated from the mutant bank was used to transform L. lactis MG1363. Transformants (approximately 28,000) were isolated from Q trays using a Genetix QPIX II-XT colony-picking robot, inoculated into 384-well plates containing GM17 freezing buffer, incubated overnight, and subsequently stored at −20°C.

Construction of lacZ- and phoA-ltnI gene fusions.

pMRC01 was used as the template to amplify, by PCR, C-terminally truncated ltnI fragments using LtnIxbaF (containing the ribosomal binding site and start codon for ltnI) as the forward primer for all constructs. The respective reverse primers are listed in Table 2. All lacZ reverse primers (LtnI21B to LtnI114B) contain a BamHI restriction site to facilitate in-frame fusion with the lacZ gene of pRMCD70 (11), whereas reverse primers for phoA fusions (LtnI21H to LtnI114H) contain a HindIII site to facilitate in-frame fusion with phoA of pRMCD28 (11). All constructs were electroporated into E. coli CC118, and transformants were selected on LB plates containing ampicillin and initially checked using a phoA or lacZ check primer situated upstream of the cloned ltnI gene fragment in conjunction with the appropriate reverse primer used to make the constructs. The integrity of the constructs was subsequently confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Table 2.

Primers used for truncation and site-directed mutagenesis of LtnI and to construct LacZ and PhoA fusions

| Primer use and name | Sequence (5′ to 3′)a |

|---|---|

| Truncation and site-directed mutagenesis of LtnI | |

| 5563F | ATGCATGCAACTATACACCTTCTT |

| 5562R | TATAAGCTTTACCATGTGCTATTGAT |

| Nterm14F | GGGCTGCAGATGTTTTACTCATTAAAAGAGTGGGCG |

| Nterm20W | GGCTGCAGATGTGGGCGGAAGGTTCAGCAAAC |

| Nterm28Y | GGGCTGCAGATGTATAATATACTTTTAGGCTTAAGT |

| Cterm83 | GTCTAGATTAAAATATTATGTCACATATAATTAG |

| Cterm90 | GTCTAGATTATGGTTGAATTAAATATCC |

| Cterm109 | GGGAAGCTTTAAAAGACAATAAATCCCACC |

| LtnID57AF | CCACAAAGATTGGGAAAAAAGGCAGAAAGAACAACTAAAATAAGTT |

| LtnID57AR | AACTTATTTTAGTTGTTCTTTCTGCCTTTTTTCCCAATCTTTGTGG |

| LtnID57Ach | CAAAGATTGGGAAAAAAGCA |

| LtnIR59AF | CCACAAAGATTGGGAAAAAAGATGAAGCAACAACTAAAATAAGTT |

| LtnIR59AR | AACTTATTTTAGTTGTTGCTTCATCTTTTTTCCCAATCTTTGTGG |

| LtnID57/R59F | CCACAAAGATTGGGAAAAAAGCAGAAGCAACAACTAAAATAAGTT |

| LtnID57/R59R | AACTTATTTTAGTTGTTGCTTCTGCTTTTTTCCCAATCTTTGTGG |

| LtnIL2AF | CTTTATGGCAAAATATGGTTTTTCTGGCCTTGTTGGTGGG |

| LtnIL2AR | CCATATTTTGCCATAAAGAATGGTTGAATTAAATATCC |

| LtnIL2Ach | CAACCATTCTTTATGGCA |

| LtnIL1AF | CCCAAAGGATATGCAATTCAACCATTCTTTATGTTAAAATATGG |

| LtnIL1AR | CCATATTTTAACATAAAGAATGGTTGAATTCGATATCCTTTGGG |

| LtnIL1Ach | ATTTCCCAAAGGATATGCA |

| pNZF | CTAATGTCACTAACCTGCCCCGTTAG |

| pNZR | GGCTATCAATCAAAGCAACACGTG |

| LtnIRMFor | GGGGTACCCTACACCTTCTTTGTTATTG |

| LtnIRMRev | GCTCTAGAGCTTATATTATTTATTATCTTTAATATAT |

| Construction of LacZ and PhoA fusions | |

| LtnIxbaF | AAATCTAGACTGGAGGACATAAGAATGAAGAATGAAAAT |

| LtnI21B | AAAGGATCCCGCCCACTCTTTTAATGAGTA |

| LtnI45B | AAAGGATCCAAAAACTACACTTGACAT |

| LtnI55B | AAAGGATCCTTTCCCAATCTTTGTGGAAATTG |

| LtnI75B | AAAGGATCCTAGAGTAATTAAAACACA |

| LtnI85B | AAAGGATCCTCCTTTGGGAAATATTAT |

| LtnI100B | AAAGGATCCGCAAGAAAAACCATATTT |

| LtnI114B | AAAGGATCCATCTTTAATATATTTTAA |

| LtnI21H | AAAAAGCTTCGCCCACTCTTTTAATGAGTA |

| LtnI45H | AAAAAGCTTAAAAACTACACTTGACAT |

| LtnI55H | AAAAAGCTTTTTCCCAATCTTTGTGGA |

| LtnI75H | AAAAAGCCTTAGAGTAATTAAAACACA |

| LtnI85H | AAAAAGCTTTCCTTTGGGAAATATTAT |

| LtnI100H | AAAAAGCTTATCTTTAATATATTTTAA |

| LtnI114H | AAAAAGCTTATCTTTAATATATTTTAAAAGAC |

| phoA/lacZ check | GCACCCCAGGCTTTACAC |

Underlining and bold represent restriction sites.

Creation of truncated LtnI proteins.

Plasmid pMRC01 was used as a template to facilitate the creation of truncated ltnI genes. The primer 5562R was used to generate all N-terminal deletion mutant constructs in combination with the forward primers Nterm14F, Nterm20W, and Nterm28Y (all containing a PstI site; Table 2). Primers 5563F, Cterm83, Cterm90, and Cterm109 were used to generate the C-terminal deletion mutant. In all cases, the PCR products were digested with the appropriate restriction enzymes, introduced downstream of the constitutive P44 promoter in pNZ44, and transformed into E. coli Top10 cells. Transformants were selected on LB-Cm plates, further analyzed by PCR, and sequenced to ensure their integrity. Plasmids were then electroporated into L. lactis MG1363 to assess the level of immunity provided.

Site-directed mutagenesis in LtnI.

Amino acids in LtnI were changed using the site-directed mutagenesis strategy (QuikChange; Stratagene), as described previously (9), using pNZ44ltnI as the template and the primers listed in Table 2. That is, the primers LtnIL1AF/R and LtnIL2AF/R were used for constructing pNZltnIL87A and pNZltnIL94A, respectively; and pNZ44ltnID57A and pNZ44ltnIR59A were created using the primers LtnID57AF/R and LtnIR59AF/R, respectively, for the single mutants. A double mutant (pNZ44ltnID57A-R59A) was created using one pair of primers (LtnID57/R59F/R) encompassing both mutations. The QuikChange procedure was used according to the manufacturer's instructions, with the exception that E. coli Top10 was used as the cloning host. Putative mutants were selected on LB-Cm plates, confirmatory PCRs were carried out using an appropriate check primer in conjunction with pNZR or 5562R, successful mutation was confirmed with DNA sequencing, and the immunity provided when these plasmids were introduced into MG1363 was assessed.

Agar-based lacticin 3147 sensitivity tests.

Using the Genetix QPIX II-XT colony-picking robot, the mutant bank was stamped onto Q trays containing GM17 seeded with various concentrations of a skimmed milk-based preparation of lacticin 3147 (lacticin 3147 fermentation; Teagasc Moorepark), a 1-mg ml−1 solution of which corresponds to 640 activity units (AU) ml−1 against the lacticin 3147-sensitive target L. lactis HP. Sensitivity to lacticin 3147 was indicated by a failure to grow in the presence of 3 mg ml−1 lacticin 3147 powder. Enhanced resistance to lacticin 3147 was screened for through exposure to 12 mg ml−1 (7,680 AU ml−1) lacticin 3147 powder. Sensitivity to lacticin 3147 was also assessed using a gradient agar sensitivity test (21). Briefly, square petri dishes (100 by 100 mm) were filled with 25 ml of GM17 containing 15 mg ml−1 lacticin 3147-milk powder, placed at approximately a 3° angle, and allowed to set. The petri dish was then placed in a horizontal position and an additional 25 ml of GM17 was added, resulting in the creation of a lacticin 3147 concentration gradient. Diluted bacterial cultures (0.5 McFarland standard unit) were applied with a sterile cotton swab along the lacticin 3147 gradient, and the dish was incubated overnight at 30°C.

Broth-based lacticin 3147 sensitivity assays.

Broth-based growth assays were performed by inoculating L. lactis MG1363/pNZ44ltnI strains to give a final inoculum of 105 CFU ml−1 in a volume of 0.2 ml in GM17 containing 1.1 μM lacticin 3147 and monitoring the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) with a Spectromax 340 spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) over a 16-h period. MIC assays were performed as described previously (12).

β-Galactosidase and alkaline phosphatase assays.

β-Galactosidase and alkaline phosphatase assays were carried out as described by Miller (38) and Manoil (32), respectively. Briefly, for LacZ constructs, E. coli cells were grown in 10 ml LB broth until the OD600 reached ∼0.5, collected by centrifugation, and resuspended in 1 ml LacZ buffer. Cells were permeabilized with 0.1% SDS and chloroform as described previously (24). Subsequently, 4 mg ml−1 2-nitrophenyl β-d-galactopyranoside (ONPG) was mixed with the permeabilized cells, the mixture was incubated at 30°C until the development of a yellow pigment, and the reaction was stopped with 1 M sodium carbonate (NaCO3). Enzymatic activities were calculated using the following formula [(522 × OD420 of reaction mixture)/(OD600 of culture × volume per ml of culture used × time of reaction)]. Miller activity per ml of culture represents the average of three triplicate experiments. To assay PhoA activity, E. coli cells were grown as described for the β-galactosidase assays, resuspended in 1 M Tris, pH 9.0, and permeabilized as before; phosphatase substrate (10 mg ml−1) was added; and samples were incubated at 37°C until the development of a yellow pigment; the reaction was stopped with 10 M sodium hydroxide (NaOH). PhoA activity was calculated using the formula [(1,000 × OD420 of reaction mixture)/(OD600 × volume of culture × time of reaction)].

RESULTS

In silico analysis of LtnI.

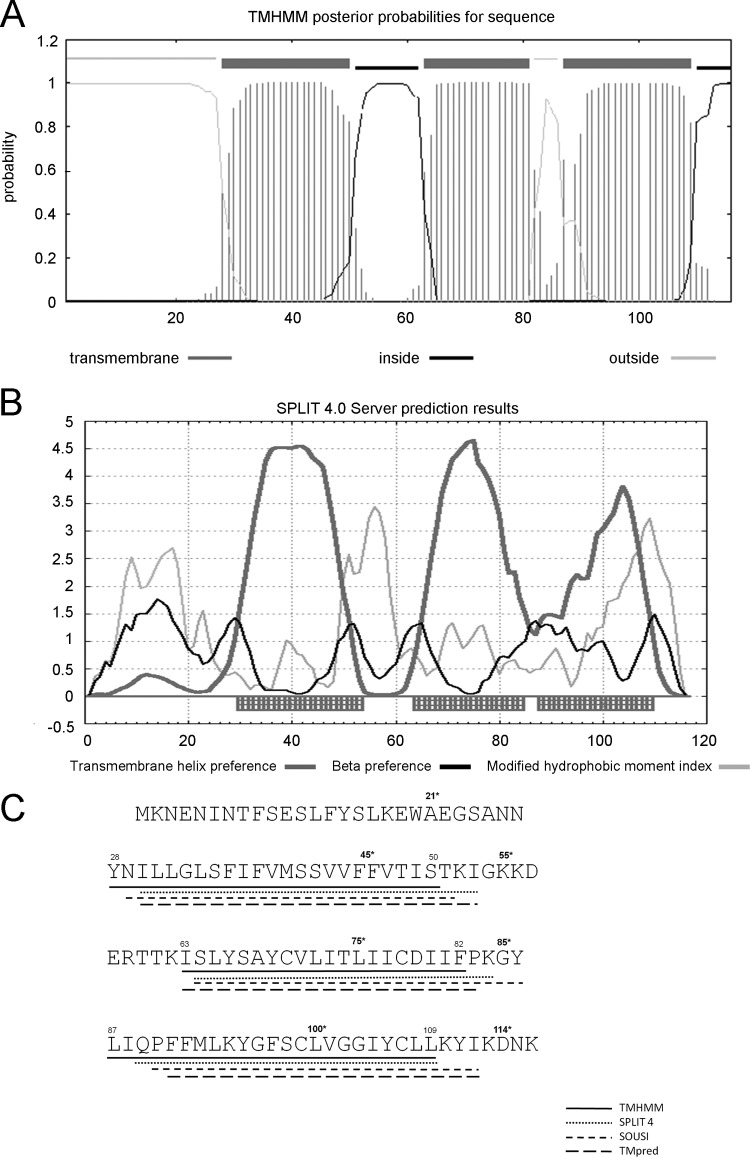

It was previously reported by McAuliffe et al. that LtnI (116 amino acids in length) is likely to be an integrated membrane protein, based on Kyte and Doolittle hydrophobicity plots that predict three highly hydrophobic domains (34). We can now report a more extensive bioinformatic analysis, using the TMHMM (29), HMMTOP (52), SPLIT (version 4.0) (26), SOUSI (20), and TMpred (22) servers, which also strongly predict that these hydrophobic regions correspond to three transmembrane domains (TMDs). All predictions suggest that the N terminus of LtnI is located outside the cell, that TMD1 and TMD3 have an outside-to-inside orientation, that TMD2 has an inside-to-outside orientation, and that the C terminus has a cytoplasmic location (Fig. 1). A study analyzing the accuracy of 13 TM helix prediction methods, including those used in this study, has highlighted the accuracy of TMHMM2 and SPLIT (version 4.0) (10), and thus, the structures predicted by TMHMM2 and SPLIT (version 4.0) were used as the templates (Fig. 1C) to design all subsequent experimentation.

Fig 1.

LtnI topology predictions. Membrane topology models of LtnI using TM prediction sites. TMHMM (A) and SPLIT (version 4.0) (B) analysis. (A) Dark grey, amino acids predicted to be in the membrane; black, amino acids inside; light grey, amino acids outside. (B) Dark grey hatched boxes indicate amino acids in the membrane. (C) On the basis of the study by Cuthbertson et al. (10), the findings obtained with different algorithms were compared to indicate LtnI transmembrane regions: TMHMM, SPLIT (version 4.0), SOUSI, and TMpred. Protein sequence of LtnI also indicates residues fused to reporter enzymes LacZ and PhoA (residues numbered and with asterisks).

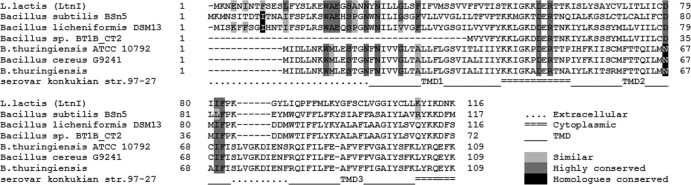

In silico analysis (PSI-BLAST; http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) has also facilitated the identification of genes encoding LtnI-like proteins from within microorganisms whose genomes have been sequenced (Fig. 2). This includes a bliI gene that has previously been shown to provide protection against lacticin 3147 when expressed heterologously (12). An alignment of the putative amino acid sequences of the LtnI-like proteins facilitates the identification of conserved regions that potentially correspond to regions that are essential to the function of these proteins. One notable feature relates to the fact that the putative cytoplasmic loop is characterized by a large number of what are mostly charged amino acids that are conserved across homologues, represented in LtnI by D57, E58, R59, and T60. Furthermore, while previous in silico investigations have predicted the presence of a leucine zipper in LtnI (34), the identification of leucine zippers can easily be assigned incorrectly when the correct orientation of leucines alone is employed. Notably, when reassessed using 2ZIP, a server for leucine zipper prediction (2), it becomes apparent that LtnI lacks other essential coiled coil segments, thus casting doubt over the existence of a leucine zipper domain. Finally, a Batch CD search (a conserved domain search tool) (33) fails to annotate functional protein domains within LtnI.

Fig 2.

Investigation of LtnI homologues. LtnI and its closest homologues derived from a variety of Bacillus strains. Highlighted are the amino acids that were involved in random or site-directed mutagenesis. The amino acids between W20 and N27 have also been investigated for homology due to the importance of this region in immunity. Where homology is conserved among homologues alone (highlighted in black) is of particular interest, as conversion of the amino acid at this position in LtnI to the corresponding conserved amino acid diminishes immunity.

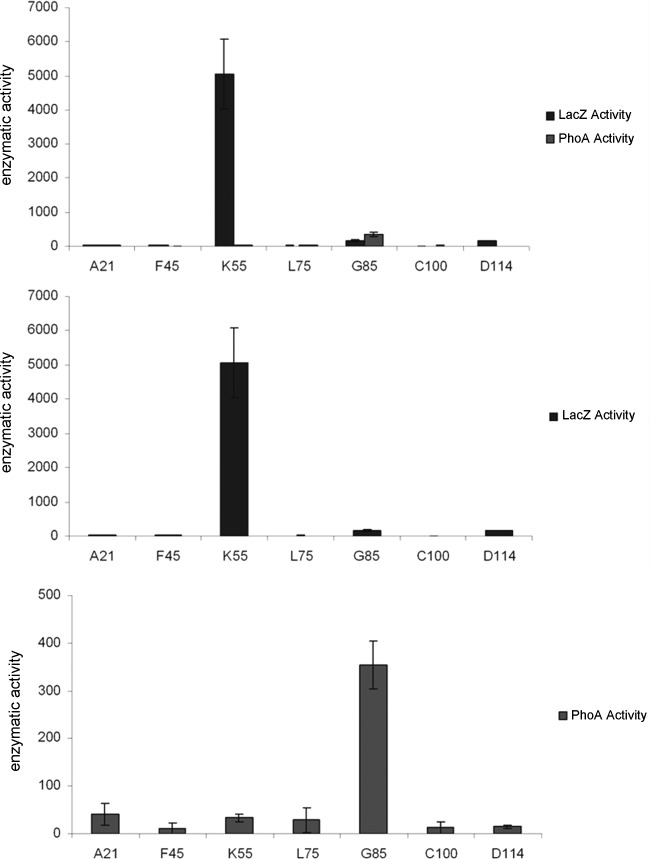

Analysis of LtnI membrane topology in E. coli using ltnI-lacZ and ltnI-phoA gene fusions.

We used β-galactosidase (lacZ) and alkaline phosphatase (phoA) gene fusions to experimentally probe LtnI membrane topology (32). The aforementioned bioinformatic analysis was used as the basis for constructing a series of constructs whereby each of the predicted inside/outside domains, including the 3 TMDs (Fig. 1C), was fused to LacZ and PhoA. Fusions of this nature can reveal the location of individual domains on the basis of the premise that enzymatically active LacZ is achieved only if it is located in the cytoplasm and active PhoA hybrids are observed only if the enzyme is located outside the cytoplasmic membrane. The low-copy-number vectors pRMCD28 (phoA) and pRMCD70 (lacZ) were utilized to fuse truncated forms of ltnI to phoA or lacZ genes lacking the first eight codons. These were under the control of a lacI promoter. Fourteen hybrids were generated. In these hybrids, LacZ and PhoA were fused to the C-terminal amino acids A21, F45, K55, L75, G85, C100, and D114 of truncated LtnI proteins. β-Galactosidase and phosphatase assays showed that the K55 hybrid had a LacZ-positive and PhoA-negative phenotype, indicating that, as predicted, K55 is located in the cytoplasm (Fig. 3). Similarly, the G85 fusions behaved as expected (LacZ negative, PhoA positive), indicating that this region is located outside the cytoplasmic membrane. A21 fusions have a LacZ- and PhoA-negative phenotype, which may be due to the production of a nonfunctional hybrid protein as a consequence of its small size or may indicate that A21 may be located in the membrane. The C-terminal region D114 fusions had a PhoA-negative phenotype and a slightly LacZ-positive phenotype, suggesting that the C terminus of LtnI is located in the cytoplasm but is in close contact with the membrane, in a manner that results in lower LacZ activity. Fusions made within putative TM regions (F45, L75, and C100) all have a LacZ- and PhoA-negative phenotype, thus indicating that these amino acids are indeed embedded in the membrane (Fig. 3).

Fig 3.

Activity of LtnI-LacZ and LtnI-PhoA fusions in E. coli CC118. Activity of ltnI-lacZ and ltnI-phoA fusions in E. coli CC118. A21, F45, etc., represent the residue of LtnI fused to lacZ or phoA. Activity is representative of the average of three independent triplicate experiments.

Design and analysis of N-terminal and C-terminal deletions of LtnI.

To further investigate the importance of different regions, truncated versions of LtnI were created. Initially, the N terminus, a region highly conserved between LtnI-like proteins, was truncated to exclude residues 1 to 13 of LtnI (abbreviated ltnIΔNT1-13), while a second mutant that lacks this region as well as residues 14 to 19 and a third mutant lacking residues 1 to 27 were also generated (Fig. 2). The construct pNZ44ltnIΔNT1-13 was cloned into MG1363 and was initially tested by well diffusion assay for an immunity phenotype. The level of immunity provided by MG1363/pNZ44ltnIΔNT1-13 was comparable to that provided by MG1363/pNZ44ltnI, as was that provided by MG1363/pNZ44ltnIΔNT1-19, a fact that was confirmed by MIC studies (Table 3). In contrast, MG1363/pNZ44ltnIΔNT1-27 was as sensitive as the control host strain MG1363, thus demonstrating that the region between W20 and N27 inclusive of the N terminus of LtnI is essential for its functionality. In contrast, it was apparent that the absence of the C-terminal region of LtnI pNZ44ltnIΔCT110-116 did not alter the immunity phenotype, with an MIC of 1.25 μM (identical to that of MG1363/pNZ44ltnI). While the removal of larger regions of the C terminus (facilitated by the creation of pNZ44ltnIΔCT90-116 and pNZ44ltnIΔCT83-116) resulted in decreased immunity, strains expressing these proteins remained quite resistant (MICs, 625 nM) relative to the sensitive host, MG1363 (Table 3).

Table 3.

MICs of N- and C-terminally truncated derivatives of LtnI

| Construct expressed in L. lactis MG1363 | MIC |

|---|---|

| MG1363 (control) | 19.5 nM |

| pNZ44ltnI | 1.25 μM |

| pNZ44ltnID57A | 1.25 μM |

| pNZ44ltnIR59A | 1.25 μM |

| pNZ44ltnID57A-R59A | 1.25 μM |

| pNZ44ltnIΔNT1-13 | 1.25 μM |

| pNZ44ltnIΔNT1-19 | 1.25 μM |

| pNZ44ltnIΔNT1-27 | 19.5 nM |

| pNZ44ltnIΔCT83-116 | 625 nM |

| pNZ44ltnIΔCT90-116 | 625 nM |

| pNZ44ltnIΔCT110-116 | 1.25 μM |

Creation and analysis of site-directed mutants in LtnI.

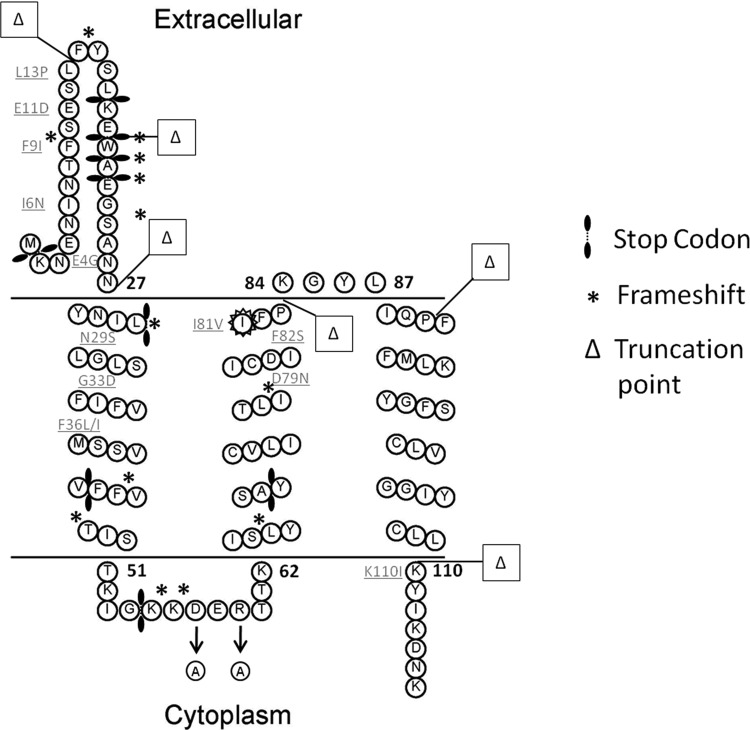

In order to investigate a role for the previously identified leucine zipper-associated residues in LtnI, residues L87 and L94 (the 1st and 2nd leucines within the motif) were individually converted to an alanine through manipulation of pNZ44ltnI and expression in MG1363. A number of conserved residues corresponding to residues D57, E58, R59, and T60 in LtnI were also investigated. One positively charged amino acid (R59) and one negatively charged amino acid (D57) within the conserved, putatively cytoplasmically located domain were converted to alanine to assess their importance. A double D57A-R59A change was also made (Fig. 4). In all cases, immunity levels were equal to those provided by pNZ44ltnI, as determined by well diffusion assays (data not shown). Subsequently, more sensitive MIC determination tests were carried out. However, it was again evident that the changes made did not impact the level of immunity provided (Table 3), thereby revealing that neither the putative leucine zipper nor the two charged residues in the cytoplasmic domain are essential for immunity.

Fig 4.

Prediction of LtnI topology with overview of mutagenesis and truncation positions. Predicted here is the membrane location of LtnI. Indicated are positions at which random mutagenesis due to amino acid changes, frameshifts, and stop codon introduction resulted in diminished immunity, or as for I81V, in which the amino acid change resulted in a functionally enhanced LtnI peptide. Positions at which truncated LtnI proteins were created are also present.

Random mutagenesis of ltnI and identification of essential residues and domains.

Given the failure of rational site-directed mutagenesis to identify residues that are important with respect to the provision of LtnI-mediated immunity, a random mutagenesis-based strategy was developed. More specifically, plasmid pNZ44ltnI was isolated and utilized as a template for a GeneMorph II PCR-based reaction that was carried out in a manner designed to result in the introduction of at least a 1-bp change in the ltnI amplicons. Ligation of these amplicons into pNZ44 and heterologous expression in L. lactis MG1363 led to the creation of a bank of 28,000 strains expressing randomly mutated forms of ltnI. Spotting of the bank onto GM17 infused with 3 mg ml−1 (1,920 AU ml−1) lacticin 3147-skim milk powder revealed more than 200 strains that were unable to grow despite PCR confirmation that a copy of the ltnI gene was present. Ninety-five representative mutants were selected for DNA sequencing to identify the changes responsible for the dysfunction of LtnI immunity (Table 4; Fig. 4). In 18 cases, disruption of immunity was as a consequence of a single amino acid substitution. These represented 12 unique mutants, as I6N, E11D, and N29S variants were each detected on two occasions, while D79N was recovered four times (Table 4). Of the 12 unique single amino acid substitutions, 5 occurred at the N terminus between amino acid positions 4 and 13. The E4G change alters the overall charge of the external N terminus of LtnI from a net charge of −2 to one of −1 by replacing glutamic acid with glycine. Conversion of the isoleucine at position 6 to an asparagine replaces a hydrophobic residue with a hydrophilic one. While the F9I mutation maintains a hydrophobic moiety at this position, it does, however, involve the loss of an aromatic ring at this position. Similarly, the mutation E11D does not alter the overall charge but does result in the loss of a carbene group. The final amino acid to be altered in the external N-terminal stretch in LtnI is leucine at position 13, which is converted to a proline.

Table 4.

Results from sequencing of 96 randomly mutated LtnI proteins susceptible to lacticin 3147

| Mutant | Change |

|---|---|

| 1 | Start codon disruption |

| 2 | N29S |

| 3 | I6N |

| 4 | K56 frameshift |

| 5 | K56 frameshift |

| 6 | K110I |

| 7 | E22 stop |

| 8 | E11D |

| 9 | K56R, T74S, C107R |

| 10 | E11D |

| 11 | >20 changes |

| 12 | D79N |

| 13 | F45 stop |

| 14 | E22 stop |

| 15 | K2 stop |

| 16 | E22K, A25P, S42R, F45 frameshift |

| 17 | K2 stop |

| 18 | K55 stop |

| 19 | L32 frameshift |

| 20 | Y69H, L87 stop |

| 21 | >20 changes |

| 22 | S10 frameshift |

| 23 | K56 frameshift |

| 24 | F82S |

| 25 | E22G, T51A, M93R |

| 26 | E4G |

| 27 | F36L |

| 28 | D79N |

| 29 | Y15 frameshift |

| 30 | S16T, M40T |

| 31 | W20 frameshift |

| 32 | L13P |

| 33 | F9I |

| 34 | G33D |

| 35 | I80T, F82C |

| 36 | >20 changes |

| 37 | K56 frameshift |

| 38 | >20 changes |

| 39 | D79N |

| 40 | K2 stop |

| 41 | Start codon disruption |

| 42 | Y15 frameshift |

| 43 | K55 stop |

| 44 | I76 frameshift |

| 45 | K56 frameshift |

| 46 | >20 changes |

| 47 | E19 frameshift |

| 48 | A21 frameshift |

| 49 | Y15 frameshift |

| 50 | K56 frameshift |

| 51 | >20 changes |

| 52 | D79N |

| 53 | T48 frameshift |

| 54 | A21V, N29S, L32 stop |

| 55 | A21V, N29S, L32 stop |

| 56 | V47 frameshift |

| 57 | Y69 stop |

| 58 | >20 changes |

| 59 | F36I |

| 60 | A21 stop |

| 61 | F46 frameshift |

| 62 | K55 stop |

| 63 | L32 frameshift |

| 64 | A21V, N29S, L32 stop |

| 65 | >20 changes |

| 66 | D57 frameshift |

| 67 | S24 frameshift |

| 68 | T8P, V47 frameshift |

| 69 | N7Y, A21V |

| 70 | S10 frameshift |

| 71 | >20 changes |

| 72 | W20 stop |

| 73 | N29S |

| 74 | I6N |

| 75 | Y15 frameshift |

| 76 | >20 changes |

| 77 | Y15 frameshift |

| 78 | >20 changes |

| 79 | >20 changes |

| 80 | Y15 frameshift |

| 81 | >20 changes |

| 82 | S24 frameshift |

| 83 | >20 changes |

| 84 | K2 stop |

| 85 | K2 stop |

| 86 | L32 stop |

| 87 | Y69 stop |

| 88 | E19 frameshift |

| 89 | L65 frameshift |

| 90 | K18 stop |

| 91 | E19 frameshift |

| 92 | N5Y, A25V, D57 frameshift |

| 93 | >20 changes |

| 94 | S24 frameshift |

| 95 | >20 changes |

| 96 | Wild type (control) |

Within the transmembrane region, there are a total of six changes resulting in a complete loss of immunity. The changes in the first membrane-spanning domain include N29S, G33D, F36I, and F36L. The change at N29S maintains the hydrophilic nature of the region, but altering this essential amino acid to a serine reduces the immunity phenotype. The second change, G33D, introduces a negative charge into the membrane. Two different changes occur at phenylalanine 36: conversion to an isoleucine and conversion to a leucine. Within the second transmembrane domain, two mutations, D79N and F82S, resulted in the elimination of activity. Replacement of the aspartic acid at position 79 with an arginine represents the loss of a negative charge, while replacement of phenylalanine at position 82 with a hydrophilic serine results in the loss of the hydrophobic moiety of this region. The final single amino acid change identified related to K110I, whereby the positively charged lysine was replaced by isoleucine, thus altering the net charge of the protein at the membrane.

Thirty-two strains expressing mutated forms of ltnI were sensitive as a consequence of frameshift mutations (Table 4; Fig. 4). These represented 16 distinct mutations, as M1, Y15, E19, S24, L32, and K56 were each altered on multiple occasions. Notably, all detrimental frameshift mutations occurred within codons corresponding to regions between residues 1 and 65 but not in more C-terminally located residues. Stop codons were introduced in 17 instances corresponding to 9 different positions, as stop codons at positions corresponding to K2, E22, K55, and Y69 were identified on more than one occasion. In all cases, these stop codons occurred within the region between residues 2 and 69. It is also noteworthy that while frameshifts have multiple effects, the effects are comparable to the effects of stop codons, as they indicate that the region after the frameshift must have been important if activity has been eliminated. In combination, the location of the detrimental frameshift and stop mutations provides further evidence that the provision of LtnI is not dependent on the presence of intact C-terminal domains.

Finally, of the 95 mutants sequenced, there were 12 incidences (10 of which were distinct) of 2 to 4 changes, changes that resulted in amino acid changes, frameshifts, and/or the introduction of stop codons; and thus, the specific change responsible for inactivity was not apparent. Finally, there were 16 cases where ≥20 changes were identified in the genes that resulted from excessive mutagenesis of ltnI.

Identification of an LtnI derivative that provides enhanced protection.

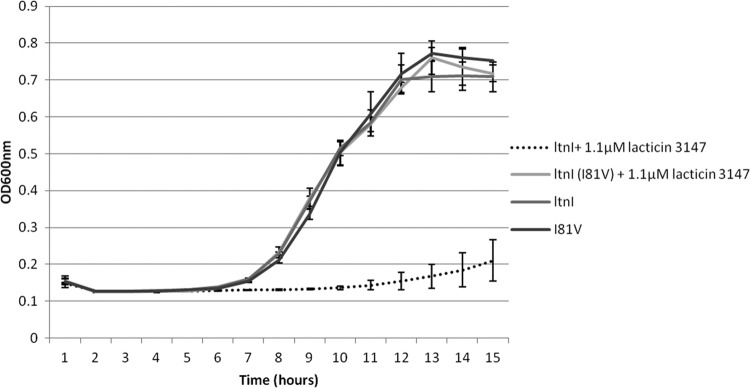

An agar-based screening strategy was employed to screen for ltnI derivatives that provide enhanced protection resulting in the ability of the host strain to grow in the presence of 12 mg ml−1 (7,680 AU ml−1) lacticin 3147-milk powder. A single mutant with an ability to survive in the presence of increased levels of lacticin 3147 was identified. To ensure that this enhanced protection was as a consequence of the ltnI-associated change rather than a spontaneous change within the host's genome, the associated pNZ44ltnI plasmid was isolated, reintroduced into a fresh MG1363 background, and found to again provide enhanced protection. The corresponding ltnI gene was sequenced, and a mutation predicted to result in an I81V change was identified. Residue 81 of LtnI is predicted to be part of the second transmembrane domain, close to the interface of the extracellular membrane. To further assess the enhanced protection provided by this change, MG1363/pNZ44ltnI and MG1363/pNZ44ltnI (I81V) were grown in the presence and absence of 1.1 μM lacticin 3147. This confirms the enhanced resistance of LtnI(I81V) to the lantibiotic (Fig. 5).

Fig 5.

Growth curve demonstrating the enhanced immunity of LtnI (I81V). MG1363/pNZ44ltnI and MG1363/pNZ44ltnI (I81V) were grown in the presence and absence of 1.1 μM lacticin 3147. Each strain was grown in triplicate, and readings of the absorbance at 600 nm were taken hourly.

DISCUSSION

The dedicated immunity proteins associated with lantibiotic production are a heterogeneous group of proteins of different sizes, compositions, and structures. They are target molecule-specific and are highly efficient in their action. NisI, SpaI, and PepI are anchored to the cytoplasmic membrane, and unusually, NisI has also been found as a lipid-free form, presumably scavenging for exogenous nisin (21, 28, 48, 49). In contrast, it was previously recognized that LtnI was very likely to traverse the membrane (34) in a manner similar to that predicted for CylI (6) and established for NukH (40). Notably, however, none of these proteins show any homology to each other.

In this study, the assessment of LtnI topology suggests that LtnI contains three transmembrane regions. This is consistent with the results obtained with the SPLIT (version 4.0) and TMHMM algorithms, which have previously been established to be 85% and 83% accurate, respectively, in predicting the location of residues (10). The biological and in silico data predict the existence of an internal loop between TMD1 and TMD2 and an external loop between TMD2 and TMD3. The predicted cytoplasmic loop has a large number of positively charged residues, and in general, such residues act as strong topogenic signals, influencing the conformation of membrane proteins in prokaryotes and eukaryotes (46, 53, 54). On the basis of an extensive study comparing integral membrane proteins from 107 genomes (both prokaryotic and eukaryotic) in which the distribution of the positively charged amino acids lysine and arginine was analyzed, it was suggested that this trend is true for all TM proteins (39). Our biological assessment of topology relied on assays carried out in E. coli. It is thus important to note that it has previously been demonstrated that topological data derived from E. coli are highly reflective of the situation in lactic acid bacteria (25). Therefore, it is likely that the topology of LtnI predicted is a true reflection of the situation in a lacticin 3147-immune L. lactis isolate.

Our targeted mutagenesis focused on specific residues and domains within LtnI. The importance of two charged amino acids within a highly conserved region of the cytoplasmic loop of LtnI was assessed by their substitution, both singly and in combination. Interestingly, unlike that observed for PepI, where loss of charged residues at the C terminus reduces immunity function (21), here in neither case was there a detrimental impact on the associated immunity phenotype, establishing that neither of these residues has a role in the immunity function of LtnI. While it may be the case that other positively charged residues in this region and/or the other topological signals within LtnI are sufficient to ensure the retention of functionality, it was notable that random mutagenesis did not reveal essential residues within this internal loop. The leucine zipper-like motif located near the C terminus of LtnI was also subjected to mutagenesis to investigate if this unusual feature had a role in the functionality of LtnI. Site-directed mutagenesis of either the 1st or 2nd leucine had no effect on the immunity phenotype, suggesting that the zipper motif has no functional role in immunity. It appears that prediction of the presence of a leucine zipper solely on the basis of bioinformatic tools identifying a distinct pattern of leucines cannot be made with confidence, and our findings would seem to indicate that the presence of the leucine repeats in LtnI may be coincidental. Truncation of the N and the C termini of LtnI revealed that the extended N terminus plays a key role in the immunity phenotype but that the latter part of the C terminus, as also seen in the case of NukH (40), is not essential. Furthermore, the removal of TMD3 alone or in conjunction with the external loop from the C terminus results in a reduction of immunity but does not eliminate immunity. This is a phenomenon also observed for NukH, whereby the TMD3 is essential only for a full immunity level (40). Interestingly, the last 7 amino acids of LtnI would not appear to make any contribution to protection, as pNZ44ltnIΔCT110-116 provided the same level of immunity as pNZ44ltnI. However, it is noteworthy that removal of a positive charge within this region (K110I) has a more dramatic impact. Such an alteration may have a knock-on effect on other, nearby regions and/or negatively impact the native structure of the protein. This is also true for the N terminus of LtnI, where removal of the negative charge at position 4 results in loss of function. In contrast, although truncation within the extended N terminus of LtnI results in inactivity (MG1363/pNZ44ltnIΔNT1-27 is not immune but MG1363/pNZ44ltnIΔNT1-20 is), no immunity-eliminating amino acid substitutions were identified between positions 20 and 27, suggesting that the region as a whole, rather than specific amino acids, is important. In contrast, substitutions involving charge (E4G) or the loss (F9I) or gain (L13P) of large or secondary structure-distorting amino acids within the region from amino acids 1 to 13 in the N terminus have a greater impact than the deletion of this entire region. The first of two absolutely essential domains identified in this study is therefore within the N terminus and contains a region between W20 and N27 (inclusive) that is essential for immunity and notably contains conserved amino acids among homologues.

With respect to the transmembrane regions, it was observed that changes resulting in loss of immunity in most cases were found close to the membrane and in all cases were confined to TMD1 and TMD2. In this regard, the use of a level of 3 mg ml−1 (1,920 AU ml−1) lacticin 3147 in agar was effective in identifying only strains in which LtnI activity was completely eliminated. From analysis of the various LtnI derivatives that have been generated in this study, it is clear that a second defined region of LtnI between I76 (where a frameshift eliminates immunity) and P83 (after which a truncated derivative retains 50% activity) is of essential importance. It can also be inferred that although TMD3 (F91 to L109) appears to be tolerant of change, its presence is essential for optimal activity. As previously mentioned, the TMD3 region of NukH is also essential for a full immunity phenotype, and another region of significance is the external loop (40). Here we found that it is a region adjacent to this loop that appears to be essential for lacticin 3147 immunity.

Finally, and perhaps most notably, we have identified an alteration that provides an immunity protein (LtnI I81V) with an enhanced ability to protect against its cognate lantibiotic. Modified lantibiotic immunity proteins with enhanced activity have not previously been described. This observation is of significant interest. The bioengineering of lantibiotic producers to generate overproducing strains or strains that produce lantibiotic derivatives with enhanced antimicrobial activity has been the focus of much attention in recent years (14). Bacteria producing these proteins need to be protected from the bactericidal agent that they are producing, and thus, self-protection may ultimately become a limiting factor. It is thus anticipated that mechanisms to enhance immunity may in turn facilitate enhanced production.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by the Irish Government under the National Development Plan, through Science Foundation Ireland Investigator awards 06/IN.1/B98 and 10/IN.1/B3027.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 16 July 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Aso Y, et al. 2005. A novel type of immunity protein, NukH, for the lantibiotic nukacin ISK-1 produced by Staphylococcus warneri ISK-1. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 69:1403–1410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bornberg-Bauer E, Rivals E, Vingron M. 1998. Computational approaches to identify leucine zippers. Nucleic Acids Res. 26:2740–2746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Breukink E, de Kruijff B. 2006. Lipid II as a target for antibiotics. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 5:321–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brumfitt W, Salton MR, Hamilton-Miller JM. 2002. Nisin, alone and combined with peptidoglycan-modulating antibiotics: activity against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and vancomycin-resistant enterococci. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 50:731–734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chatterjee C, Paul M, Xie L, van der Donk WA. 2005. Biosynthesis and mode of action of lantibiotics. Chem. Rev. 105:633–684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Coburn PS, Hancock LE, Booth MC, Gilmore MS. 1999. A novel means of self-protection, unrelated to toxin activation, confers immunity to the bactericidal effects of the Enterococcus faecalis cytolysin. Infect. Immun. 67:3339–3347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cotter PD, Hill C, Ross RP. 2005. Bacteriocins: developing innate immunity for food. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3:777–788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cotter PD, Hill C, Ross RP. 2003. A food-grade approach for functional analysis and modification of native plasmids in Lactococcus lactis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:702–706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cotter PD, et al. 2005. Posttranslational conversion of l-serines to d-alanines is vital for optimal production and activity of the lantibiotic lacticin 3147. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:18584–18589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cuthbertson JM, Doyle DA, Sansom MS. 2005. Transmembrane helix prediction: a comparative evaluation and analysis. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 18:295–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Daniels C, Vindurampulle C, Morona R. 1998. Overexpression and topology of the Shigella flexneri O-antigen polymerase (Rfc/Wzy). Mol. Microbiol. 28:1211–1222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Draper LA, et al. 2009. Cross-immunity and immune mimicry as mechanisms of resistance to the lantibiotic lacticin 3147. Mol. Microbiol. 71:1043–1054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Draper LA, Ross RP, Hill C, Cotter PD. 2008. Lantibiotic immunity. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 9:39–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Field D, Hill C, Cotter PD, Ross RP. 2010. The dawning of a ‘golden era’ in lantibiotic bioengineering. Mol. Microbiol. 78:1077–1087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Galvin M, Hill C, Ross RP. 1999. Lacticin 3147 displays activity in buffer against gram-positive bacterial pathogens which appear insensitive in standard plate assays. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 28:355–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gasson MJ. 1983. Plasmid complements of Streptococcus lactis NCDO 712 and other lactic streptococci after protoplast-induced curing. J. Bacteriol. 154:1–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Guder A, Schmitter T, Wiedemann I, Sahl HG, Bierbaum G. 2002. Role of the single regulator MrsR1 and the two-component system MrsR2/K2 in the regulation of mersacidin production and immunity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:106–113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Guder A, Wiedemann I, Sahl HG. 2000. Posttranslationally modified bacteriocins—the lantibiotics. Biopolymers 55:62–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Heidrich C, et al. 1998. Isolation, characterization, and heterologous expression of the novel lantibiotic epicidin 280 and analysis of its biosynthetic gene cluster. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:3140–3146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hirokawa T, Boon-Chieng S, Mitaku S. 1998. SOSUI: classification and secondary structure prediction system for membrane proteins. Bioinformatics 14:378–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hoffmann A, Schneider T, Pag U, Sahl HG. 2004. Localization and functional analysis of PepI, the immunity peptide of Pep5-producing Staphylococcus epidermidis strain 5. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:3263–3271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hofmann K, Stoffel W. 1993. TMbase—a database of membrane spanning proteins segments. Biol. Chem. Hoppe-Seyler 374:166 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Holo H, Nes IF. 1995. Transformation of Lactococcus by electroporation. Methods Mol. Biol. 47:195–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Israelsen H, Madsen SM, Johansen E, Vrang A, Hansen EB. 1995. Environmentally regulated promoters in lactococci. Dev. Biol. Stand. 85:443–448 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Johnsborg O, Diep DB, Nes IF. 2003. Structural analysis of the peptide pheromone receptor PlnB, a histidine protein kinase from Lactobacillus plantarum. J. Bacteriol. 185:6913–6920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Juretic D, Zoranic L, Zucic D. 2002. Basic charge clusters and predictions of membrane protein topology. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 42:620–632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Klein C, Entian KD. 1994. Genes involved in self-protection against the lantibiotic subtilin produced by Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6633. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:2793–2801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Koponen O, Takala TM, Saarela U, Qiao M, Saris PE. 2004. Distribution of the NisI immunity protein and enhancement of nisin activity by the lipid-free NisI. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 231:85–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Krogh A, Larsson B, von Heijne G, Sonnhammer ELL. 2001. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J. Mol. Biol. 305:567–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kruszewska D, et al. 2004. Mersacidin eradicates methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in a mouse rhinitis model. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 54:648–653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kuipers OP, Beerthuyzen MM, Siezen RJ, De Vos WM. 1993. Characterization of the nisin gene cluster nisABTCIPR of Lactococcus lactis. Requirement of expression of the nisA and nisI genes for development of immunity. Eur. J. Biochem. 216:281–291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Manoil C. 1991. Analysis of membrane protein topology using alkaline phosphatase and beta-galactosidase gene fusions. Methods Cell Biol. 34:61–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Marchler-Bauer A, et al. 2011. CDD: a conserved domain database for the functional annotation of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 39:D225–D229 doi:10.1093/nar/gkq1189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. McAuliffe O, Hill C, Ross RP. 2000. Identification and overexpression of ltnl, a novel gene which confers immunity to the two-component lantibiotic lacticin 3147. Microbiology 146(Pt 1):129–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. McAuliffe O, Ross RP, Hill C. 2001. Lantibiotics: structure, biosynthesis and mode of action. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 25:285–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. McGrath S, Fitzgerald GF, van Sinderen D. 2001. Improvement and optimization of two engineered phage resistance mechanisms in Lactococcus lactis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:608–616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Meyer C, et al. 1995. Nucleotide sequence of the lantibiotic Pep5 biosynthetic gene cluster and functional analysis of PepP and PepC. Evidence for a role of PepC in thioether formation. Eur. J. Biochem. 232:478–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Miller JH. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nilsson J, Persson B, von Heijne G. 2005. Comparative analysis of amino acid distributions in integral membrane proteins from 107 genomes. Proteins 60:606–616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Okuda K, et al. 2005. Characterization of functional domains of lantibiotic-binding immunity protein, NukH, from Staphylococcus warneri ISK-1. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 250:19–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Otto M, Peschel A, Gotz F. 1998. Producer self-protection against the lantibiotic epidermin by the ABC transporter EpiFEG of Staphylococcus epidermidis Tu3298. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 166:203–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Pag U, Heidrich C, Bierbaum G, Sahl HG. 1999. Molecular analysis of expression of the lantibiotic pep5 immunity phenotype. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:591–598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pag U, Sahl HG. 2002. Multiple activities in lantibiotics—models for the design of novel antibiotics? Curr. Pharm. Des. 8:815–833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Peschel A, Gotz F. 1996. Analysis of the Staphylococcus epidermidis genes epiF, -E, and -G involved in epidermin immunity. J. Bacteriol. 178:531–536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sipos L, von Heijne G. 1993. Predicting the topology of eukaryotic membrane proteins. Eur. J. Biochem. 213:1333–1340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Skaugen M, Abildgaard CI, Nes IF. 1997. Organization and expression of a gene cluster involved in the biosynthesis of the lantibiotic lactocin S. Mol. Gen. Genet. 253:674–686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Stein T, Heinzmann S, Dusterhus S, Borchert S, Entian KD. 2005. Expression and functional analysis of the subtilin immunity genes spaIFEG in the subtilin-sensitive host Bacillus subtilis MO1099. J. Bacteriol. 187:822–828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Stein T, Heinzmann S, Solovieva I, Entian KD. 2003. Function of Lactococcus lactis nisin immunity genes nisI and nisFEG after coordinated expression in the surrogate host Bacillus subtilis. J. Biol. Chem. 278:89–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Suda S, Cotter PD, Hill C, Ross RP. 2012. Lacticin 3147—biosynthesis, molecular analysis, immunity, bioengineering and applications. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 13:193–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Takala TM, Saris PE. 2006. C terminus of NisI provides specificity to nisin. Microbiology 152:3543–3549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Tusnady GE, Simon I. 2001. The HMMTOP transmembrane topology prediction server. Bioinformatics 17:849–850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. von Heijne G. 1989. Control of topology and mode of assembly of a polytopic membrane protein by positively charged residues. Nature 341:456–458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. von Heijne G. 2006. Membrane-protein topology. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7:909–918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wiedemann I, et al. 2001. Specific binding of nisin to the peptidoglycan precursor lipid II combines pore formation and inhibition of cell wall biosynthesis for potent antibiotic activity. J. Biol. Chem. 276:1772–1779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]