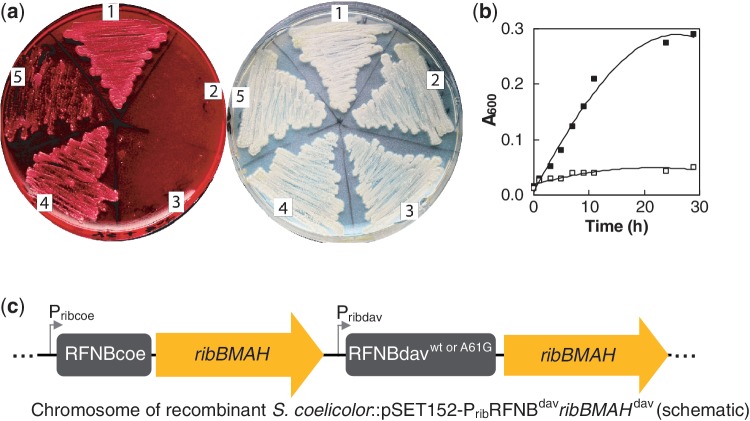

Figure 5.

The S. davawensis FMN riboswitch confers roseoflavin resistance to S. coelicolor. Spores of different Streptomyces strains were applied to each of the sectors of the YS plates shown (1, wild-type S. davawensis; 2, wild-type S. coelicolor; 3, S. coelicolor::pSET152; 4, S. coelicolor::pSET152-PribRFNBdavribBMAHdav and 5, S. coelicolor:: pSET152-PribRFNBdavA61GribBMAHdav), and the plates were aerobically incubated at 30°C for 60 h. The recombinant S. coelicolor in sector 4 was generated by introducing the S. davawensis ribBMAH cluster into the chromosome of S. coelicolor by homologous recombination. The strain in sector 3 is a control containing empty pSET152 at Φ31. The recombinant S. coelicolor in sector 5 was generated by introducing the S. davawensis ribBMAH-genes (including the roseoflavin-sensitive A61G mutant FMN ribB riboswitch). (a) The plate to the left contained 200 µM roseoflavin, and the plate to the right did not contain any antibiotic. The spores in sector 5 of the left plate produced less mycelium when compared with the spores in sector 4. (b) Growth of the strains S. coelicolor::pSET152-PribRFNBdavribBMAHdav (solid squares) and S. coelicolor::pSET152-PribRFNBdavA61GribBMAHdav (open squares) was also monitored in a liquid culture (minimal medium). (c) Schematic drawing showing the chromosome of recombinant S. coelicolor strains containing two different gene clusters controlled by two different promoters (with very similar activity) and two different FMN ribB riboswitches (RFNBcoe, from S. coelicolor, and RFNBdav from S. davawensis).