Abstract

This review illustrates a wide spectrum of gastric neoplasms with emphasis on imaging findings helpful in characterizing various gastric neoplasms. Both the malignant and benign neoplasms along with focal gastric masses mimicking tumour are illustrated. Moreover, imaging clues to reach an accurate diagnosis are emphasized.

Keywords: Stomach, cancer, CT, gastric neoplasm, imaging, mimickers of stomach cancer

Introduction

Multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) offers an excellent evaluation of the gastric lumen, gastric wall and the adjacent structures. MDCT has a primary role in characterizing several gastric conditions while in others it complements upper gastrointestinal fluoroscopy and endoscopy in establishing the diagnosis and defining the extent of the disease. This article reviews the cross-sectional imaging features of common and uncommon neoplastic gastric pathologies with emphasis on imaging clues that help to diagnose a particular gastric tumour. It also highlights the imaging features in certain diseases that can potentially mimic gastric neoplasia.

MDCT technique

An optimum computed tomography (CT) technique requires high spatial resolution, optimal gastric distension, and proper timing of contrast media injection to detect subtle changes in the gastric wall and to accurately stage tumours. When CT is performed specifically to evaluate the stomach, the patient is given 750 ml of water approximately 15 min before scanning. An additional 250 ml may be given immediately prior to the study. Non-ionic contrast material (120 ml at a rate of 3 ml/s) and an arterial phase (30 s after contrast injection) and venous phase (60 s after contrast injection) are required for accurate tumour staging and characterization. When imaging a patient with known gastric disease, we use 4×1.0-mm collimator setting. Sections 1.25-mm thick are then generated and reformatted at 1-mm intervals. With advanced CT scanners (16–256 slice) collimation thickness as low as 0.2 mm may be obtained. Two-dimensional and three-dimensional multiplanar reformations are also generated. In addition, CT data of the stomach can be manipulated to simulate endoscopic images (virtual gastroscopy). Administration of effervescent and hypotonic agents (butyl scopolamine) to improve gastric distension and prone imaging for better delineation of the proximal stomach are some of the techniques that may be used for optimal evaluation of a specific gastric pathology.

Gastric adenocarcinoma

Adenocarcinoma is the most common gastric malignancy, representing over 95% of malignant tumours of the stomach. About 30% of cancers are located in the antrum, 30% in the body, and 30% in the fundus or cardia region[1]. The remaining 10% are diffusely infiltrating lesions that involve the entire stomach. Signet-ring cell carcinomas account for 5–15% of all gastric cancers and typically cause scirrhous infiltration of the gastric wall[1].

Gastric adenocarcinoma can manifest on CT as focal wall thickening with or without ulceration, polypoidal mass or diffuse infiltration (linitis plastica). Wall thickening >1 cm that is focal, eccentric, and enhancing favours malignancy[2]. However, smooth wall thickening of the distal gastric antrum relative to the proximal stomach on MDCT with or without submucosal low attenuation may be a normal finding. Antral wall thickness commonly exceeds 5 mm and may measure up to 12 mm[3]. Signet-ring cell cancer usually manifests as a scirrhous tumour of the stomach that leads to obliteration of gastric folds and diffuse thickening of the gastric wall (linitis plastica) (Fig. 1). In early advanced gastric cancers (T2), malignant invasion is limited to the muscularis propria or serosa and the outer border may be smooth or show a few small linear strands of soft tissue extending into the perigastric fat, as is the case with a desmoplastic or inflammatory reaction (Fig. 2). The probability of transmural extension of the tumour (T3) is directly correlated with mural thickness. In transmural extension, the serosal contour becomes blurred and strandlike areas of increased attenuation may be seen extending into the perigastric fat (Fig. 3). Tumour spread frequently occurs via ligamentous and peritoneal reflections to adjacent organs (T4). MDCT has a reported accuracy of 77.1–88.9% in determining T-stage with a major limitation being differentiating T2 lesions from T3 lesions[2].

Figure 1.

A 58-year-old man with gastric carcinoma. Oblique coronal contrast-enhanced CT reveals diffuse thickening (arrows) and enhancement of the gastric wall in the distal stomach with obliteration of the gastric folds and decreased distension in the affected region. This is classic Linitis plastica and on pathology was a T3 signet-ring cell carcinoma. This subtype of gastric carcinomas frequently involves the distal half of the stomach, is often understaged and has a higher rate of peritoneal spread.

Figure 2.

Contrast CT demonstrates a large polypoidal mass (arrows) along the lesser curvature of the stomach with a smooth outer gastric wall and the absence of perigastric stranding signifying T2 gastric carcinoma.

Figure 3.

Coronal contrast CT shows focal markedly enhancing wall thickening in the antrum (circle) with resultant gastric outlet obstruction. There is an irregular border with a blurred fat plane along the medial margin (arrow) signifying T3 carcinoma.

Lymphatic spread is found in 74–88% of patients with gastric carcinoma because of the abundant lymphatic vessels in the stomach[1]. The frequency of lymphatic metastases is related to the size and depth of penetration of the tumour. N staging depends on the number of positive perigastric lymph nodes (N1, 1–5; N2, 6–15; and N3, >15 affected lymph nodes)[1]. MDCT has an accuracy of 51–97% in lymph nodal staging of gastric cancers[4].

Haematogenous metastases from gastric carcinoma most commonly involve the liver because the stomach is drained by the portal vein. Other less common sites of haematogenous spread include the lungs, adrenal glands, kidneys, bones, and brain.

Lymph node involvement outside the perigastric location is considered M1 disease. Advanced cancers can develop peritoneal metastases[1]. Some patients with signet-ring cell gastric carcinomas may have intraperitoneally seeded metastases to the ovaries, which are known as Krukenberg tumours (Fig. 4).

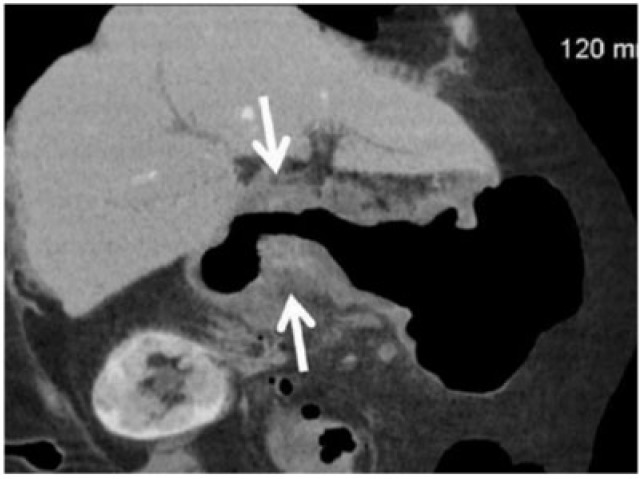

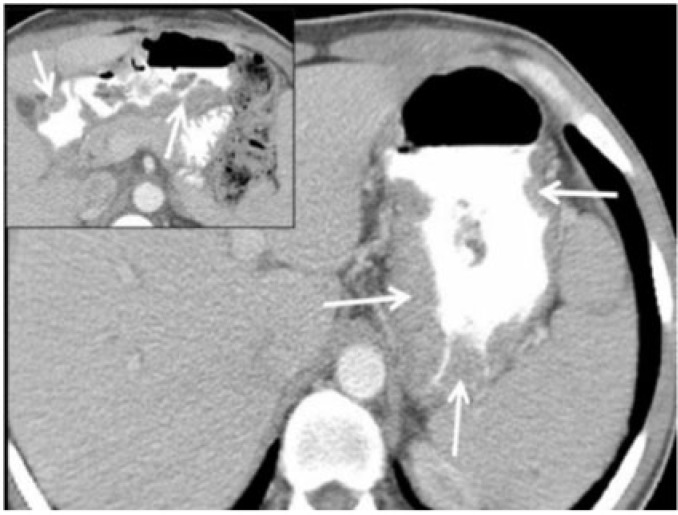

Figure 4.

Surgically proven infiltrative mucinous gastric carcinoma in a 45-year-old man. Coronal contrast CT reveals diffuse low attenuation thickening of the gastric wall with punctuate calcifications (arrows). The thin high-attenuating inner layer (arrowhead) is preserved while the middle and outer layers show low density thickening; this along with the punctate calcifications favours mucinous adenocarcinoma. Inset: image at the level of the pelvis reveals bilateral complex solid cystic masses (arrows) consistent with ovarian metastases or Krukenberg tumours. Mucinous gastric carcinoma is a rare subtype of gastric carcinoma and has a poorer prognosis than other subtypes.

Gastric lymphoma

Gastric lymphoma represents 1–5% of malignant tumours of the stomach[5]. Primary gastric lymphomas are confined to the stomach and regional lymph nodes. They comprise about 35% of gastrointestinal lymphomas and are predominantly non-Hodgkin lymphomas of B-cell origin[5]. Lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) is a distinct type of extranodal lymphoma that is characterized by a relatively indolent clinical course and has a much better prognosis than gastric carcinoma, with overall 5-year survival rates of 50–60%[1]. There is evidence linking Helicobacter pylori gastritis with the development of lymphomas of the MALT type. High-grade B-cell lymphoma has a relatively aggressive course as opposed to the more indolent and favourable outcome of MALT lymphoma (Fig. 5). In high-grade gastric lymphomas, the extent of disease is usually greater at presentation, with involvement of adjacent organs and perigastric lymph nodes. Most cases involve the antrum and body, although the entire stomach can be involved. Transpyloric spread of tumour into the duodenum occurs in about 30% of patients[1,5].

Figure 5.

Low-grade gastric lymphoma in a 45-year-old man presenting with loss of appetite and dyspepsia. Axial CT demonstrates segmental circumferential, poorly enhancing homogeneous thickening of the distal body of the stomach (arrowheads). The perigastric fat planes are maintained and there is no gastric outlet obstruction. There were no enlarged lymph nodes. Biopsy revealed MALT lymphoma, a relatively indolent form of lymphoma with a good prognosis.

There are four gross pathologic types of gastric lymphoma. Infiltrative gastric lymphomas manifest as focal or diffuse enlargement of gastric folds due to submucosal spread of tumour. One or more ulcerated lesions characterize ulcerative gastric lymphoma. Polypoidal gastric lymphomas are characterized by intraluminal masses that may simulate polypoid carcinomas. Multiple submucosal nodules ranging in size between several millimetres and several centimetres characterize nodular gastric lymphoma[1,5].

The typical CT appearance of gastric lymphoma is segmental or diffuse gastric wall thickening of usually more than 1 cm (average 2.9–5 cm). Diffuse homogeneous wall thickening with less pronounced enhancement and maintained perigastric fat planes help differentiate gastric lymphoma from cancer (Fig. 6). Transpyloric spread and bulky adenopathy below the level of the renal hilum also favour lymphoma[3]. Despite extensive lymphomatous infiltration, the stomach usually remains pliable and distensible without significant luminal narrowing or obstruction. Perforation and fistulization are known complications, especially after chemotherapy (Fig. 7). Other than gastric cancer, causes of diffuse wall thickening of the stomach, including Menetrier disease, infiltrative metastases and inflammatory disorders, are potential mimickers of lymphoma.

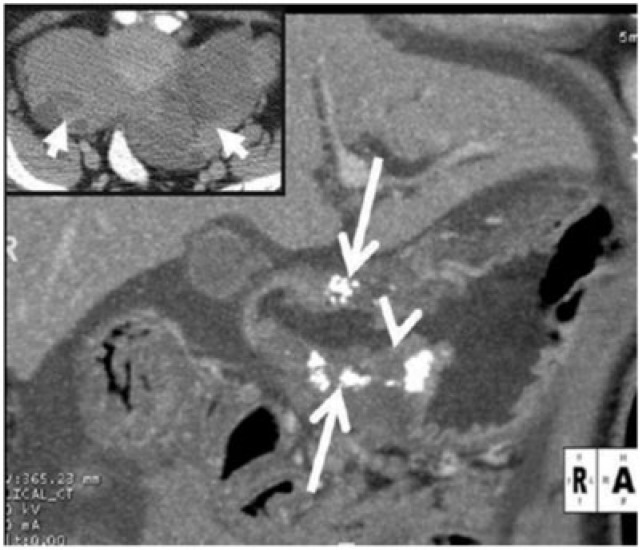

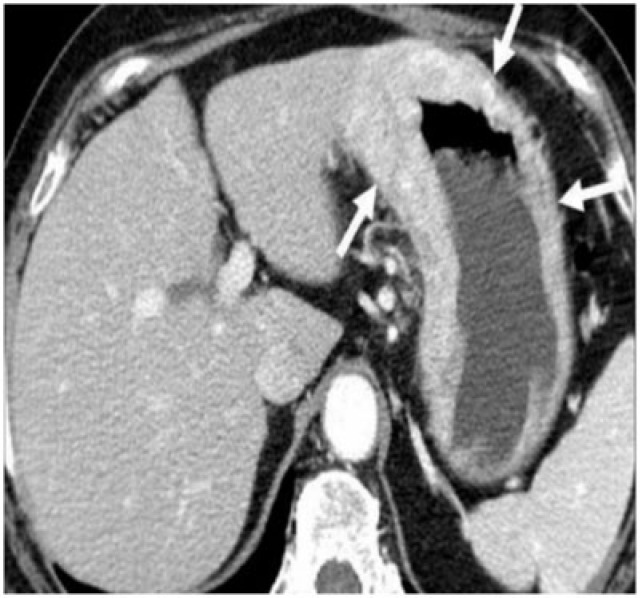

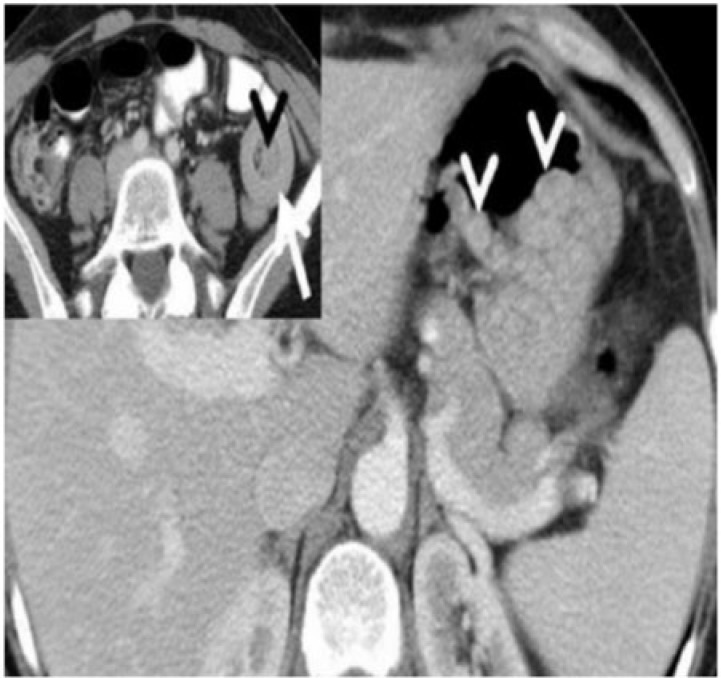

Figure 6.

A 45-year-old man with large B-cell gastric lymphoma and peritoneal lymphomatosis. Axial contrast-enhanced CT shows diffuse concentric, homogeneous thickening of the gastric wall (arrowheads) measuring 4–5 cm with maintained perigastric fat planes. Inset: image at the level of the lower pole of the kidneys reveals diffuse infiltration of the omentum (white arrows) and extensive mesenteric (arrowheads) and retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy (black arrows). The presence of lymph nodes below the renal hilum, as in this case, would be unusual in metastatic lymphadenopathy from gastric carcinoma and favours lymphoma.

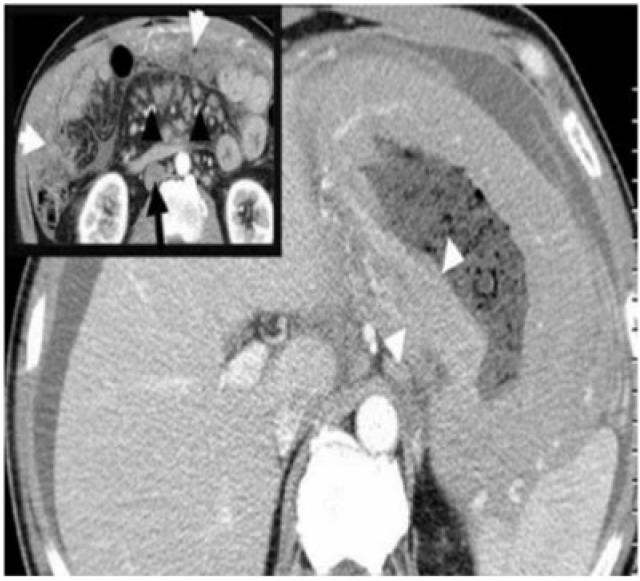

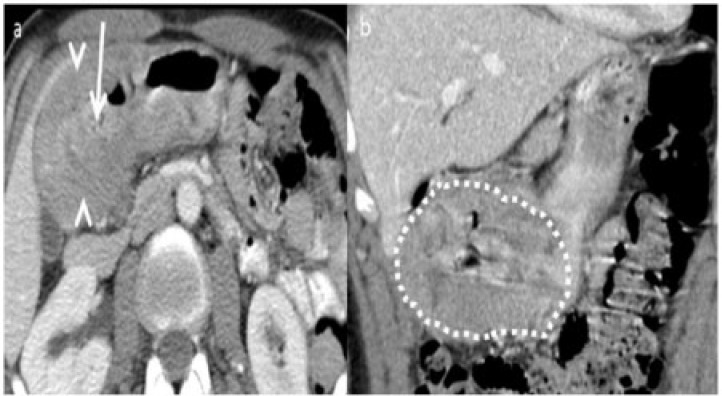

Figure 7.

Diffuse large B-cell gastric lymphoma infiltrating the spleen. (a) Axial contrast-enhanced CT reveals bulky a heterogeneous mass (arrows) infiltrating the spleen (arrowheads). (b) Follow-up coronal contrast-enhanced CT after four cycles of chemotherapy shows localized perforation of the stomach (arrows) with extensive adjacent infiltration by the mass. The patient was referred for surgery and underwent splenectomy and partial gastrectomy, which demonstrated gastric perforation and fistulization with the spleen.

Gastrointestinal stromal tumour

Gastrointestinal stromal tumour (GIST) is the most common mesenchymal tumour of the gastrointestinal tract with 60–70% of the tumours affecting the stomach[6]. The typical CT appearance is of a large (average 3–10 cm), predominantly exophytic, and hypervascular mass with areas of heterogeneity due to of necrosis, haemorrhage, or cystic degeneration (Fig. 8). Mucosal ulceration or fistulization may be seen in 15–50% of cases and manifest on CT as the presence of air or oral contrast within the mass[1,6]. Calcification is seen in 5–10% of cases[6]. Size larger than 5 cm, presence of an ulcer or necrosis, mesenteric fat or adjacent organ infiltration and metastases favour malignant GIST[1,6] (Figs. 9 and 10). Preoperative biopsy of suspected GISTs has been controversial because of the potential risks of haemorrhage and tumour seeding into the peritoneal cavity[7].

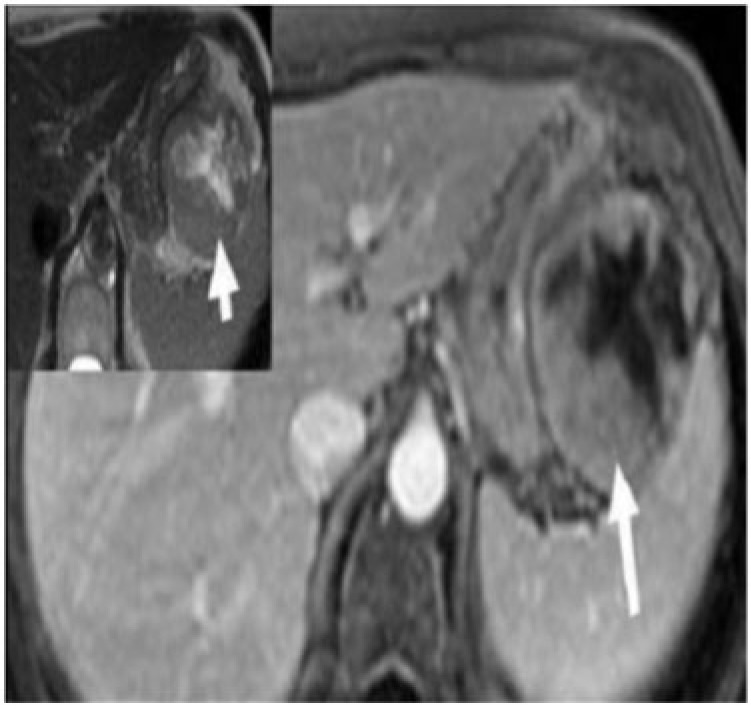

Figure 8.

Malignant gastric GIST in a 54-year-old man presenting with gastrointestinal bleeding and epigastric pain. Axial enhanced MRI demonstrates a large, well-defined mass with a predominant exogastric component (white arrow) arising from the greater curvature. There is an avidly enhancing peripheral component with central non-enhancing necrosis. Inset: image reveals the mass to be intermediate to high signal intensity (arrow) on T2-weighted MRI.

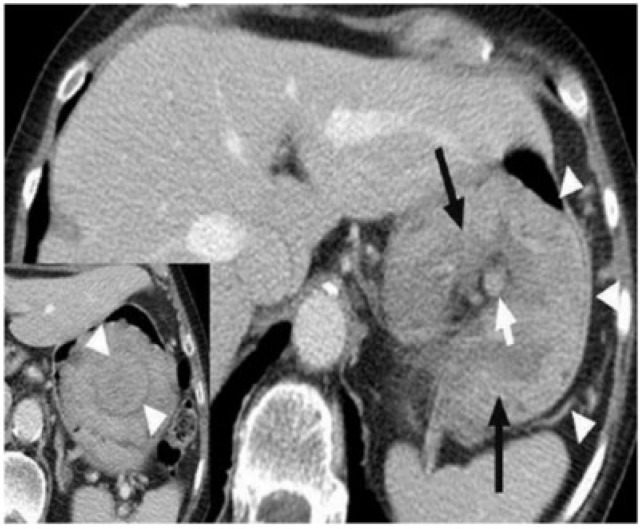

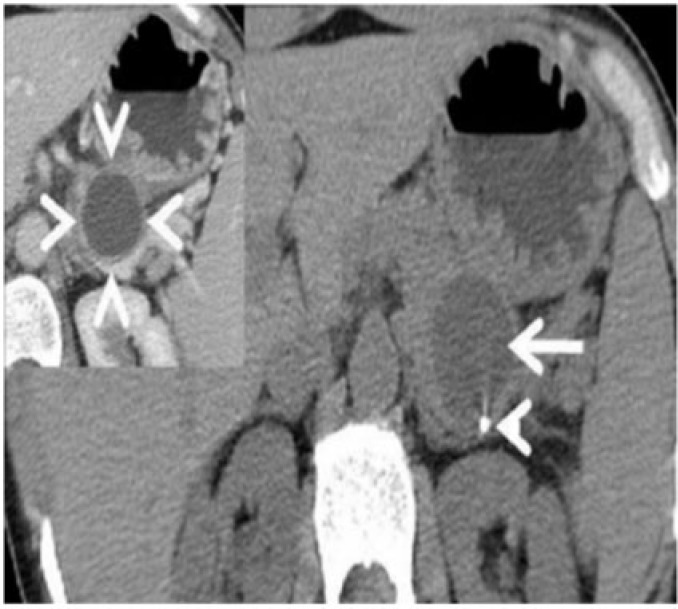

Figure 9.

A 62-year-old man with malignant GIST. Coronal contrast-enhanced CT reveals a large, lobulated, heterogeneous mass with extensive contiguous peritoneal spread (arrowheads). It is compressing the stomach (arrow).

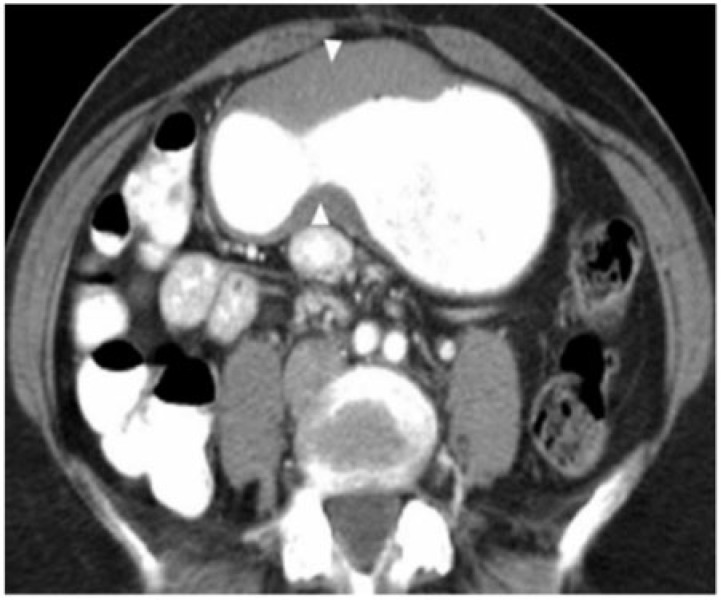

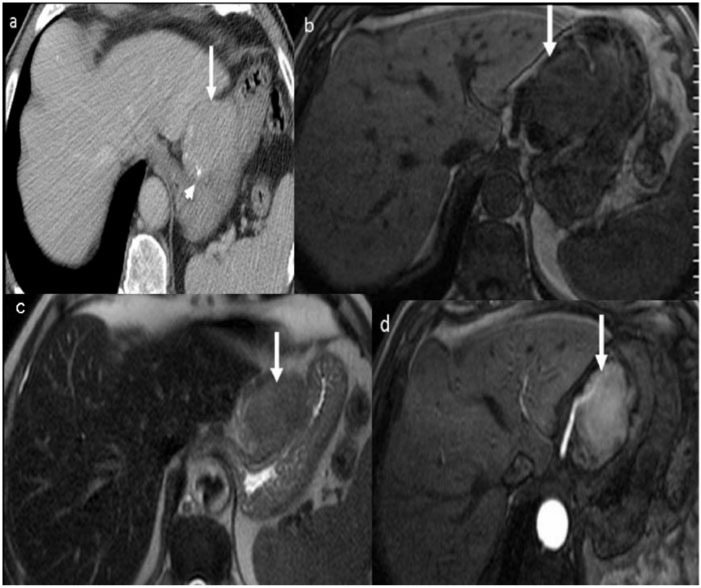

Figure 10.

Surgically proven gastro-gastric intussusception with malignant gastric GIST as the lead point. Axial contrast-enhanced CT reveals opacified blood vessels and mesenteric fat (white arrow) within intussusceptum (black arrow), which represents the lesser curvature of the stomach. The thin outline of the intussuscipiens is barely perceived (arrowheads). Inset: caudal axial section reveals a homogeneously enhancing mass as the lead point (arrowheads). Pathology revealed it to be a malignant GIST. True gastro-gastric intussusception is extremely rare and has been reported in polyps or in a gastric remnant through gastrojejunal anastomosis.

Gastric carcinoids

Gastric carcinoids are rare tumours and comprise approximately 0.3% of all gastric tumours[8]. Based on their clinical, imaging and pathological differences they are classified into three distinct types by Bordi et al.[8] (Fig. 11) (Table 1). More recently, neuroendocrine tumours of the gastrointestinal tract have been grouped with gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumours, which is a pathological classification with important prognostic implications[9].

Figure 11.

Type III gastric carcinoid in a 39-year-old man with carcinoid syndrome. (a) Axial contrast-enhanced CT shows a solitary homogeneous exogastric mass (arrow) arising from the lesser curvature with multiple calcific foci within it (arrowhead). (b) Axial T1-weighted and (c) T2-weighted MRI shows the mass (arrow) to be hypointense on the T1-weighted image and mildly hyperintense on the T2-weighted image. (d) Contrast-enhanced arterial phase MRI reveals the mass (arrow) is intensely hypervascular.

Table 1.

Classification of gastric carcinoids

| Gastric carcinoid | Frequency (%) | Association | Carcinoid syndrome | CT features | Metastases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type 1 | 80 | Chronic atrophic gastritis, pernicious anaemia, hypergastrinaemia | − | Usually <1 cm, multicentric mucosal and submucosal masses | Usually benign |

| Type 2 | 5–10 | Zollinger–Ellison syndrome, multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN-1), hypergastrinaemia | − | Multiple small masses with gastric wall thickening | Lymph node metastases |

| Type 3 | 10–15 | Sporadic, no hypergastrinaemia | + | Large solitary hypervascular mass with exophytic component | Hematogenous metastases |

Metastases

Metastases to the stomach are uncommon and most occur through haematogenous spread from melanoma, breast, lung and ovarian cancers[10]. They usually present on CT as smooth submucosal masses (Fig. 12). Haematogenous dissemination from infiltrating lobular breast carcinoma can cause metastatic linitis plastica with diffuse thickening and enhancement of the gastric wall (Fig. 13).

Figure 12.

Metastases to the stomach in a 45-year-old man with a history of treated superficial spreading melanoma of the back. Contrast-enhanced CT reveals multiple smooth submucosal masses (arrows) with hypodense centre (arrowhead) mimicking the bull’s eye appearance. Metastases were confirmed on histopathology.

Figure 13.

A 58-year-old woman with gastric linitis plastica from metastatic lobular carcinoma of the breast. Contrast-enhanced CT shows a diffusely thickened and enhancing gastric wall (arrows). There were also multiple lung and hepatic metastases (not shown).

Kaposi sarcoma

Kaposi sarcoma is the most common AIDS-associated malignancy. Kaposi sarcoma is caused by a subtype of herpes virus, and now occurs almost exclusively in homosexual or bisexual men infected by human immunodeficiency virus. The neoplasm is multicentric and can involve the skin, solid viscera, gastrointestinal tract, and mucous membranes. Kaposi sarcoma involves the gastrointestinal tract in about 40–50% of affected individuals, with the stomach being involved in 15% of cases[11]. Submucosal masses with fold thickening are seen on CT (Fig. 14). Bulky lymphadenopathy may develop in the mesentery and retroperitoneum, and intense lymph node enhancement at CT is highly suggestive of the disease in the appropriate clinical context.

Figure 14.

Kaposi sarcoma of the stomach in a 32-year-old HIV-positive man. Axial CT with oral contrast reveals multifocal variable sized submucosal nodules (arrows) in the stomach. Inset: image reveals well-defined nodules (arrows) in the antropyloric region and proximal duodenum. The skin and gastrointestinal tract are the most common organs involved in Kaposi sarcoma and within the gastrointestinal tract, the stomach and small bowel are most commonly affected.

Neural tumours

Gastric neural tumours are benign submucosal neoplasms and comprise 4% of all benign gastric neoplasms[12]. They have non-specific imaging characteristics and are indistinguishable from other submucosal gastric lesions. CT features are a well-demarcated, homogeneous, solid ovoid or multilobulated mass (Fig. 15). An exogastric component may be present. Uncommonly ulceration, calcification or cystic change may occur. Contrast enhancement is variable[12]. Gastric neural tumour may be a part of the Carney triad; the other two components being pulmonary chondroma and extra-adrenal paraganglioma.

Figure 15.

Gastric neurogenic tumour in a 29-year-old man with epigastric pain. Inset: axial non-contrast CT shows a predominantly exophytic submucosal mass (arrow) arising from the fundus of the stomach with a speck of calcification within it (arrowhead). Axial contrast-enhanced CT at the same level demonstrates mild homogeneous enhancement within the mass (arrow). A large exogastric component and calcification are not typical features of gastric neural tumours. Enhancement is variable but usually less than that seen in GIST.

Gastric lipomas

Gastric lipomas are solitary submucosal lesions usually detected incidentally in asymptomatic patients. They comprise 2–3% of gastric benign tumours and 5% of all gastrointestinal lipomas[13]. The antrum is the most common site. CT features are a solitary, submucosal, well-demarcated lesion with homogeneous fat attenuation (Fig. 16). Occasionally, linear strands of soft tissue at the base or mild adjacent gastric wall thickening may be present. Complications are rare, but larger lesions may present with ulceration, haemorrhage, intussusception and obstruction[13].

Figure 16.

Gastric lipoma incidentally detected in a 36-year-old woman. Axial non-contrast CT demonstrates a well-defined submucosal endogastric fat density mass (arrow) in the fundus of the stomach. There is minimal adjacent gastric wall thickening (arrowhead).

Gastric polyps

Non-neoplastic gastric polyps include hyperplastic and hamartomatous polyps. Hyperplastic polyps constitute 80–90% of all gastric polyps; hamartomatous polyps are seen in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, juvenile polyposis syndrome and Cronkhite-Canada syndrome[14]. Typical CT findings are multiple smooth, sessile, clustered round or oval lesions measuring 5–10 mm in size, usually located in the fundus or body of the stomach (Fig. 17).

Figure 17.

Gastric and small bowel hamartomatous polyps in a 16-year-old boy with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Axial contrast-enhanced CT reveals multiple clustered, sessile, homogeneously enhancing polyps in the body of the stomach (arrowheads). Inset: caudal sections of the pelvis reveal small bowel intussusception (arrow) with a polyp as the lead point (arrowhead).

Adenomatous polyps have malignant potential and harbour carcinomatous foci in 40% of cases. They are solitary and commonly occur adjacent to the antrum. They are larger than hyperplastic polyps with an average size of >2 cm[1,14]. Occasionally they can be multiple and distributed throughout the stomach especially when associated with syndromes like familial polyposis coli, Turcot syndrome and Gardner syndrome (Fig. 18).

Figure 18.

Adenomatous gastric polyps in a 28-year-old man with familial polyposis coli. Axial contrast-enhanced CT reveals innumerable sessile and pedunculated polyps (arrows) measuring 1–4 cm distributed diffusely in the stomach. Biopsy confirmed that many of these harboured malignant foci.

Focal masses mimicking tumour

A number of conditions can mimic the appearance of neoplastic processes in the stomach. The importance of knowing these entities cannot be underestimated given the implications for management.

Inflammatory pseudotumour

Occasionally benign gastric lesions may mimic neoplasms; some like inflammatory pseudotumours have a non-specific appearance on CT and the differentiation with a neoplasm can be made only on histology. In the abdomen, inflammatory pseudotumour or myofibroblastic tumour is seen most commonly in the terminal ileum and greater curvature of stomach. There is predominance in females and preschool-age children[15]. CT appearance is of a hypodense to isodense mass on unenhanced scans with variable to no enhancement. It may have aggressive features including ulceration and exogastric extension (Fig. 19). Calcification has been reported[15].

Figure 19.

Myofibroblastic tumour in a 14-year-old girl with epigastric pain. Axial non-contrast CT shows a well-defined, hypodense mass (arrow) arising from the body of the stomach with a predominant exogastric component. A speck of calcification is seen at the periphery of the mass (arrowhead). Inset: contrast-enhanced CT demonstrates peripheral enhancement of the lesion (arrowheads). Intraoperatively the lesion was arising from the gastric serosa. Pathology revealed it to be a myofibroblastic tumour.

Ectopic pancreatic rest

Heterotopic pancreas is rare and is most commonly found in the stomach. It is usually located along the greater curvature in the prepyloric region. CT findings are a 1–3 cm, well-defined oval to round, submucosal lesion, indistinguishable from other submucosal lesions. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is diagnostic as heterotopic pancreas follows the signal and enhancement patterns of the pancreas[16] (Fig. 20). Small cystic areas within the mass represent dilated anomalous ducts.

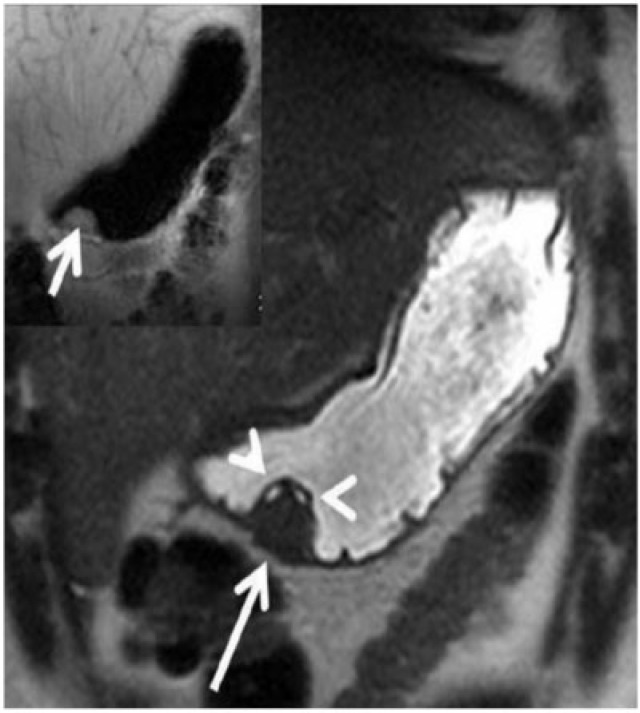

Figure 20.

Ectopic pancreatic rest in a 35-year-old man presenting with gastrointestinal bleeding. Coronal T2-weighted MRI demonstrates a well-defined submucosal lesion along the prepyloric greater curvature of the stomach (arrow). The lesion parallels the signal intensity of the pancreas on the T2-weighted image. A few small cystic areas within the lesion were confirmed to be an anomalous dilated duct on pathology. Inset: coronal T1-weighted MRI reveals the lesion (arrow) to be mildly hyperintense on the T1-weighted image, again following the signal intensity of the pancreas.

Gastric outlet obstruction due to scarring

Thickening of the pylorus with stenosis is a rare cause of gastric outlet obstruction in adults and may be primary or secondary related to scarring of a gastric/duodenal ulcer, postoperative adhesions or carcinoma. CT findings include smooth circumferential pyloric wall thickening. The pylorus is elongated and narrow with an intact smooth border giving rise to the cervix sign[17] (Fig. 21). Gastric distension is present due to gastric outlet obstruction. It is indistinguishable from carcinoma on imaging and endoscopic biopsy usually provides the diagnosis.

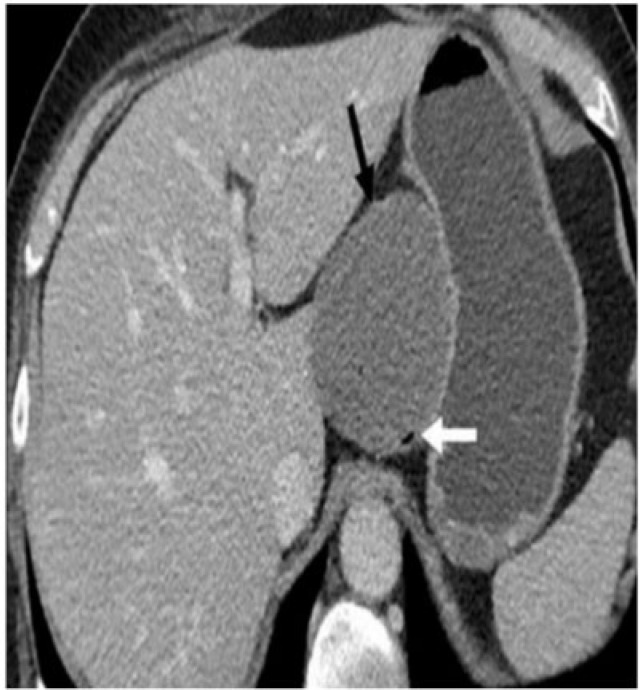

Figure 21.

Adult hypertrophic pyloric stenosis secondary to scarring of a gastric ulcer in a 54-year-old man presenting with abdominal pain and vomiting for 6 months. (a) Axial contrast CT reveals circumferential smooth wall thickening of the antropyloric region (arrowheads) with narrowing and elongation of the pylorus (arrow). (b) Coronal CT further confirms wall thickening and narrowing of the pylorus and the appearance resembles that of a cervix (cervix sign) (dotted). A preoperative diagnosis of carcinoma was made. The patient underwent distal gastrectomy and pathology, which showed it to be benign wall thickening from hypertrophic pyloric stenosis.

Gastric abscess

Gastric abscess is an uncommon condition representing a localized form of suppurative gastritis[18]. MDCT findings include localized thickening of the gastric wall or focal mass with heterogeneous enhancement (Fig. 22). Fluid or air within the mass and adjacent inflammatory stranding may be present.

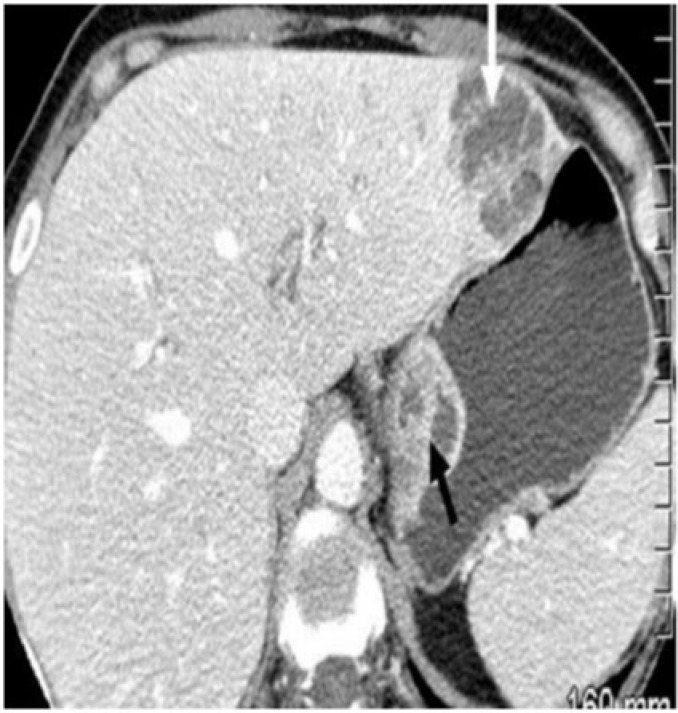

Figure 22.

A 65-year-old patient with AIDS with intramural gastric and liver abscess. Axial contrast-enhanced CT revealed heterogeneously enhancing masses in the wall of the stomach (black arrow) and liver (white arrow). Biopsy revealed abscess in both the liver and stomach with gram-negative organisms.

Gastric duplication cyst

Gastric duplication cyst is the least common of the enteric duplications with the common age of presentation being the first decade[19]. Typical CT appearance is a spheric or ovoid non-enhancing cyst close to the greater curvature. Occasionally, peripheral enhancement or marginal calcification may be present[19] (Fig. 23).

Figure 23.

Gastric duplication cyst in a 21-year-old woman presenting with epigastric pain. Contrast-enhanced CT revealed a cystic lesion (black arrow) along the medial wall of the fundus with an air speck (white arrow) within it suggesting communication with the stomach. There is no significant enhancement. Pathology confirmed gastric mucosa within the cystic lesion.

Conclusion

Cross-sectional imaging often helps differentiate benign from malignant gastric pathologies. It also helps in detection and staging of gastric neoplasms and accurately characterizes various gastric neoplasms. Familiarity with imaging findings helps to formulate the correct diagnosis and guide effective and timely management.

Footnotes

This paper is available online at http://www.cancerimaging.org. In the event of a change in the URL address, please use the DOI provided to locate the paper.

References

- 1.Ba-Ssalamah A, Prokop M, Uffmann M, et al. Dedicated multidetector CT of the stomach: spectrum of diseases. RadioGraphics. 2003;23:625–644. doi: 10.1148/rg.233025127. . PMid:12740465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Insko EK, Levine MS, Birnbaum BA, et al. Benign and malignant lesions of the stomach: Evaluation of CT criteria for differentiation. Radiology. 2003;228:166–171. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2281020623. . PMid:12759472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pickhardt PJ, Asher DB. Wall thickening of the gastric antrum as a normal finding: multidetector CT with cadaveric comparison. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;181:973–979. doi: 10.2214/ajr.181.4.1810973. PMid:14500212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Habermann CR, Weiss F, Riecken R. Preoperative staging of gastric adenocarcinoma: comparison of helical CT and endoscopic US. Radiology. 2004;230:465–471. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2302020828. . PMid:14752188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghai S, Pattison J, Ghai S, et al. Primary gastrointestinal lymphoma: spectrum of imaging findings with pathologic correlation. RadioGraphics. 2007;27:1371–1388. doi: 10.1148/rg.275065151. . PMid:17848697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim H-C, Lee JM, Kim KW, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the stomach: CT findings and prediction of malignancy. AJR. 2004;183:893–898. doi: 10.2214/ajr.183.4.1830893. PMid:15385278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hong X, Choi H, Loyer EM, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor: role of CT in diagnosis and in response evaluation and surveillance after treatment with imatinib. RadioGraphics. 2006;26:481–495. doi: 10.1148/rg.262055097. . PMid:16549611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levy AD, Sobin LH. Gastrointestinal carcinoids: imaging features with clinicopathologic comparison. RadioGraphics. 2007;27:237–257. doi: 10.1148/rg.271065169. . PMid:17235010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tan EH, Tan CH. Imaging of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. World J Clin Oncol. 2011;2:28–43. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v2.i1.28. . PMid:21603312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Green LK. Hematogenous metastases to the stomach. A review of 67 cases. Cancer. 1990;65:1596–1600. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19900401)65:7<1596::AID-CNCR2820650724>3.0.CO;2-5. . PMid:2311070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pantongrag-Brown L, Nelson AM, Brown AE, et al. Gastrointestinal manifestations of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: radiologic-pathologic correlation. RadioGraphics. 1995;15:1155–1178. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.15.5.7501857. PMid:7501857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park SO, Han JK, Kirn TK, et al. Unusual gastric tumours: radiologic pathologic correlation. RadioGraphics. 1999;19:1435–1446. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.19.6.g99no051435. PMid:10555667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferrozzi F, Tognini G, Bova D, et al. Lipomatous tumours of the stomach: CT findings and differential diagnosis. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2000;24:854–858. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200011000-00006. . PMid:11105700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Merino S, Saiz A, Moreno MJ, et al. CT evaluation of gastric wall pathology. Br J Radiol. 1999;72:1124–1131. doi: 10.1259/bjr.72.863.10700834. PMid:10700834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Narla LD, Newman B, Spottswood SS, et al. Inflammatory pseudotumor. RadioGraphics. 2003;23:719–729. doi: 10.1148/rg.233025073. . PMid:12740472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okuhata Y, Maebayashi T, Furuhashi S, et al. Characteristics of ectopic pancreas in dynamic gadolinium-enhanced MRI. Abdom Imaging. 2008;35:85–87. doi: 10.1007/s00261-008-9491-6. . PMid:19048331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horton KM, Fishman EK. Current role of CT in imaging the stomach. RadioGraphics. 2003;23:75–87. doi: 10.1148/rg.231025071. . PMid:12533643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khan M, Leya J, Dhillon S. An unusual case of recurrent gastric abscess. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;4:641–643. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berrocal T, Torres I, Gutierrez J, et al. Congenital anomalies of the upper gastrointestinal tract. RadioGraphics. 1999;19:855–872. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.19.4.g99jl05855. PMid:10464795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]