Abstract

Despite recent advances, metastatic renal cell carcinoma remains largely an incurable disease. Vascular endothelial growth factor and mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors have provided improvements in clinical outcomes. High-dose interleukin 2 remains an option for highly selected patients and is associated with durable remissions in a small minority of patients. The toxicity profiles of specific agents and patient characteristics and comorbidities and costs have an important role in the current choice of therapy. Major challenges encountered in developing molecular biomarkers to guide therapy are tumour heterogeneity and standardisation of tissue collection and analysis. Although biomarkers are in their infancy of development, they should be a priority in early preclinical and clinical development in order to guide rational tailored development of emerging agents.

Keywords: renal cell carcinoma, biomarkers, prognostic, predictive

Systemic therapy for clear cell (CC)-renal cell carcinoma (RCC) has been dramatically altered with the addition of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors to the therapeutic armamentarium (Table 1) However, most patients are not cured and the median progression-free survival (PFS) is 8–12 months in the first-line setting and 4–5 months following VEGF inhibitors. In the absence of biomarkers predictive for activity, patients are currently selected based on eligibility criteria in pivotal phase III trials, patient preferences, toxicity profiles, comorbidities and costs.

Table 1. Current algorithm for management of advanced RCC.

| Setting | Patients | Primary therapy | Other options |

|---|---|---|---|

| First line | Good or intermediate riska | Sunitinib Bevacizumab+IFN Pazopanib | HD IL-2 Sorafenib Observation |

| Poor riska | Temsirolimus | Sunitinib Pazopanib | |

| Second line | Post cytokine | Sorafenib Pazopanib Axitinib | Sunitinib Bevacizumab Temsirolimus |

| Post VEGF inhibitor | Everolimus Axitinib | Other VEGF inhibitors Temsirolimus | |

| Post mTOR inhibitor | Axitinib | Other VEGF inhibitors | |

| Third line | Post TKI→TKI | Everolimus | Temsirolimus |

| Post mTOR→TKI or Post TKI→mTOR | Different TKI | Rechallenge TKI |

Abbreviations: HD=high dose; IFN=interferon; IL=interleukin; mTOR=mammalian target of rapamycin; TKI=tyrosine kinase inhibitor; VEGF=vascular endothelial growth factor.

Based on anaemia, hypercalcaemia, KPS<80%, time from diagnosis to treatment <1 year and high LDH (Motzer et al, 2002); prognostic factors identified in patients receiving first-line VEGF-targeting therapy were: anaemia, hypercalcaemia, KPS <80%, time from diagnosis to treatment <1 year, neutrophilia and thrombocytosis (Heng et al, 2009).

Given the modest increments provided by VEGF and mTOR inhibitors coupled with their toxicities and comorbidities prevalent in RCC patients, optimal patient selection is necessary to maximise outcomes. There is a need to incorporate molecular factors in clinical decision making to optimise the therapeutic index and facilitate more rational therapy. This review focuses on biomarkers to guide the therapy of metastatic CC-RCC.

Candidate molecular biomarkers based on tumour biology

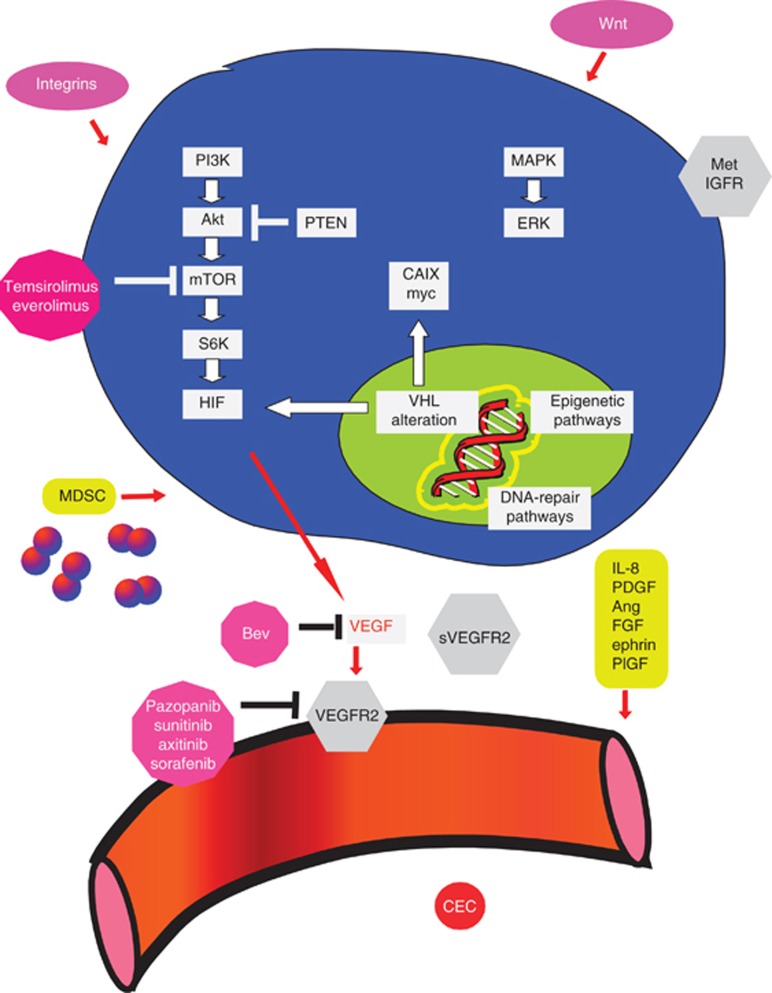

A knowledge of molecular biology and mechanisms of resistance is necessary to provide insights to develop predictive biomarkers (Figure 1) (Bergers and Hanahan, 2008). Tumour tissue amplifications of relevant genes or proteins in the pathways targeted by the agent or the alternative pathways that mediate resistance may be hypothesised to guide therapy. In addition, host genomics may modulate drug metabolism and mediate activity, toxicities and outcomes. Somatic mutations or loss of the tumour suppressor, Von Hippel Lindau (VHL) by the epigenetic pathways, frequently occurs in CC-RCC. Loss of VHL function upregulates hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF), a transcription factor that leads to the amplification of VEGF, in addition to a number of other growth factors (Kaelin, 2008). Indeed, alternative pro-angiogenic pathways (interleukin-8, fibroblast growth factor, ephrin and the angiopoietin–Tie pathways) may drive tumorigenesis. The mTOR pro-survival pathway lies downstream of the PI3K/Akt pathway and is regulated by the PTEN tumour-suppressor gene. The mTOR phosphorylation induces translation of messenger RNAs encoding cell-cycle regulators and transcription factors that promote proliferation, including HIF. The mTOR inhibition can be expected to directly inhibit tumour cell proliferation, as well as inhibit growth factors regulated by HIF, including VEGF production. The mTORC1 inhibition has been reported to upregulate the PI3K/AKT pathway, which may engender compensatory mTORC2 signalling. The alternative pathways that enhance epithelial mesenchymal transition, invasion, metastasis (for example, hepatocyte growth factor-MET, insulin-like growth factor and Wnt), metabolic pathways, proliferation (ERK/MAPK and c-myc) and immunosuppression (for example, by myeloid derived suppressor cells) may also drive growth and resistance (Gordan et al, 2008; Paez-Ribes et al, 2009; Brannon et al, 2010; Huang et al, 2010; Finke et al, 2011).

Figure 1.

Candidate molecular biomarkers for the therapy of advanced RCC with VEGF or mTOR inhibitors. Abbreviations: Bev=bevacizumab; CEC=circulating endothelial cells; FGF=fibroblast growth factor; HIF=hypoxia-inducible factor; IGFR=insulin-like growth factor receptor; IL-8=interleukin-8; MDSC=myeloid-derived suppressor cells; PDGF=platelet derived growth factor; PlGF=placental growth factor; VEGFR2=VEGF receptor 2; VHL=Von Hippel Lindau.

Potential molecular predictive biomarkers to current systemic agents

High-dose (HD) interleukin (IL)-2

Histological factors

The HD IL-2 remains an important component of decision making due to ∼7% of selected patients enjoying durable remissions. In addition to the benefit in a small minority of patients, the toxicities, especially ∼3 potential toxic death rate suggest the need for predictive biomarkers. In a retrospective analysis of 163 patients receiving HD IL-2, those with non-CC-RCC or with CC-RCC with papillary, no alveolar and/or >50% granular features appeared to respond poorly (Upton et al, 2005).

Tumour tissue factors

Although historical data suggested that high tumour CAIX (expression in >85% tumour cells) may be predictive for benefit from HD IL-2, the phase II SELECT trial (n=120) failed to demonstrate the predictive value of tumour CAIX expression on overall response rate (Leibovich et al, 2003; Atkins et al, 2005; McDermott et al, 2010). Specifically, the trial did not demonstrate a doubling of response rate in the clinically defined good risk group compared with the poor risk group. Conversely, the clinical high-risk SANI (Survival after Nephrectomy and Immunotherapy) group demonstrated a dismal PFS, suggesting that clinicopathological features may help select patients unlikely to benefit from HD IL-2. The SANI score is composed of lymph node status, constitutional symptoms, location of metastases (site other than lung or bone or multiple sites of metastases), sarcomatoid histology and TSH level (Leibovich et al, 2003).

Vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors

Histological factors

In a retrospective study, a higher clear-cell component was independently associated with better outcomes from VEGF receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors (Choueiri et al, 2010). It has also been observed in phase II trials that non-CC-RCC demonstrates substantially lower response rates and PFS with VEGF inhibitors, compared with CC-RCC (Choueiri et al, 2008a; Lee et al, 2012b). Among patients with sarcomatoid RCC, partial responses with VEGF inhibitors were limited to patients who had underlying CC histology and <20% sarcomatoid elements (Golshayan et al, 2009).

Tumour tissue factors

In a retrospective study of 123 patients receiving sunitinib, sorafenib, axitinib or bevacizumab, VHL inactivation was not associated with overall response, PFS or overall survival (OS). However, those with loss-of-function mutations (frameshift, nonsense, splice and in-frame deletions/insertions) had a significantly higher response rate compared with those with wild-type VHL, even after adjustment for several clinical variables (52% vs 31%, P=0.04) (Choueiri et al, 2008b). Another study (n=118) identified heterogeneity in tumour responsiveness to sunitinib or sorafenib according to CAIX status (Choueiri et al, 2010). Although CAIX expression had no prognostic value, it appeared to be predictive for response to sorafenib. When examining high vs low tumour CAIX expression by IHC, the mean tumour regresion was −17% vs −25% for sunitinib and −13% vs +9% for sorafenib therapy (P=0.05). Nevertheless, a follow-up study looking at patients treated on the TARGET trial (133 evaluable with baseline tumour tissue out of 903 enrolled) did not corroborate CAIX (by IHC) to be either predictive or prognostic in patients receiving sorafenib (Qu et al, 2012). In another study of 43 patients, frozen tumour HIF levels (by western blot) were associated with sunitinib sensitivity (Patel et al, 2008). Patients with high tumour HIF1α or HIF2α were significantly more likely to respond to sunitinib, relative to tumours containing low levels. A total of 92% (12 out of 13) tumours with high HIF2α vs 13% (2 of 15) with no detectable HIF2α responded. Supportive evidence was provided by RCC cells lines where 5 out of 10 lines showing high HIF1α and 2α by western blot were sensitive to sunitinib. Sunitinib decreased pS6K and HIF2α rapidly in vitro, but did not inhibit the phosphorylation of activated receptor tyrosine kinases, AKT or ERK. Moreover, downregulation of HIF by insertion of VHL into sensitive cells conferred resistance.

Plasma studies

Plasma proteins were analysed to identify biomarkers in a subset of patients enrolled in the Treatment Approaches in Renal Cancer Global Evaluation Trial that evaluated sorafenib vs placebo (Escudier et al, 2009; Pena et al, 2010). Baseline biomarker data were available for VEGF (n=712), soluble (s)-VEGFR-2 (n=713), CAIX (n=128), tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase (TIMP)-1 (n=123), Ras p21 (n=125) and VHL mutational status (n=134). Higher performance status correlated with elevated baseline VEGF and VHL mutations, whereas higher risk grouping correlated with elevated VEGF, CAIX and TIMP-1. Analyses identified baseline VEGF, CAIX, TIMP-1 and Ras p21 as prognostic for survival, but not predictive for benefit. Nevertheless, patients with baseline VEGF concentrations in the highest quartile gained the most PFS benefit from sorafenib. The TIMP-1 remained prognostic for survival in a multivariable analysis model that included performance status, risk group and other biomarkers. In the placebo cohort, TIMP-1 and Ras p21 levels increased at 12 weeks. In the sorafenib cohort, VEGF levels increased, whereas sVEGFR-2 and TIMP-1 levels decreased. However, baseline sVEGFR-2 and changes in VEGF or sVEGFR-2 with treatment were not predictive of response.

The concentrations of 52 plasma cytokine and angiogenic factors (CAFs) were measured in patients receiving sorafenib alone or with interferon (IFN) (n=69) to identify an association with outcomes (Zurita et al, 2012). A CAF signature (osteopontin, VEGF, CAIX, collagen IV, VEGF receptor-2 and tumour necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) correlated with PFS benefit from the combination, whereas another signature predicted benefit from sorafenib alone. Levels greater than the cut-off were associated with shorter PFS in the combination arm for all markers except TRAIL, which showed the opposite effect. Although changes in angiogenic factors were frequently attenuated by the sorafenib+IFN combination, most immunomodulatory mediators increased.

Following one cycle of sunitinib in a nonrandomised phase II trial enrolling cytokine-pretreated patients (n=63), VEGF and placental growth factor plasma levels commonly increased >3-fold relative to baseline (Deprimo et al, 2007). The sVEGFR-2 and sVEGFR-3 levels decreased and tended to return to near baseline after 2 weeks of treatment. Overall, significantly larger changes in VEGF, sVEGFR-2 and sVEGFR-3 levels were observed in responding patients. Furthermore, baseline sVEGFR-3 and VEGF-C below the median were associated with better outcomes in a phase II trial (n=61) that evaluated sunitinib following prior bevacizumab exposure (Rini et al, 2008). One group of investigators studied 85 patients that received sunitinib and identified baseline serum VEGF and neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin as prognostic, independent of clinicopathological factors (Porta et al, 2010). In a phase II study (n=225) in metastatic RCC receiving pazopanib, response correlated with a decrease in plasma sVEGFR2 (P=0.00002) but not with tumour VHL status or other soluble markers (sVEGFR1, VEGF and CEC) (Hutson et al, 2008, 2010).

Host genetic factors

Host genetics, which governs drug metabolism and the constitution of the microenvironment in which the tumour resides, can be anticipated to have an impact on clinical outcomes. Germline variants in angiogenesis and exposure-related genes were demonstrated to potentially predict response to pazopanib in a retrospective analysis of 397 evaluable patients from a phase III trial (Xu et al, 2011). Three polymorphisms in IL-8 and HIF1α and five polymorphisms in HIF1α, NR1I2 and VEGF-A were associated with outcomes (Table 2). Compared with the wild-type AA genotype, the IL-8 2767TT genotype exhibited inferior median PFS (48 vs 27 weeks, P=0.009). The HIF1A 1790AG genotype was associated with inferior outcomes compared with the wild-type GG genotype (median PFS, 20 vs 44 weeks; P=0.03). Reductions in RR were detected for the NR1I2-25385TT genotype, compared with the wild-type CC genotype (37% vs 50%, P=0.03), and for the VEGFA-1498CC genotype compared with the TT genotypes (33% vs 51%). In another study of 63 patients treated with sunitinib, VEGF single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)-634 was associated with HTN and a combination of VEGF SNP 936 and VEGFR2 SNP 889 genotypes was associated with survival (Kim et al, 2012). Interestingly, in the setting of advanced breast cancer receiving bevacizumab, certain VEGF genotypes were associated with hypertension and appeared to derive a preferential benefit (Schneider et al, 2008). In another study, IL-4 promoter variants carried prognostic value in metastatic RCC, possibly through regulation of immune surveillance (Kleinrath et al, 2007). Similarly, SNPs in VEGF and MDM2 appeared prognostic (Hirata et al, 2007; Kawai et al, 2007).

Table 2. Reported potentially predictive molecular biomarkers in advanced RCC.

| Author (reference) | Number of patients | Tissue | Biomarker | Therapeutic agent | Predictive finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Choueiri et al, 2008b | 123 | Tumour | VHL mutations | Sorafenib or sunitinib | VHL loss of functions had higher RR than wild-type VHL |

| Choueiri et al, 2010 | 118 | Tumour | CAIX | Sorafenib or sunitinib | CAIX amplification associated with response to sorafenib but not sunitinib |

| Qu et al, 2012 | 133 | Tumour | CAIX | Sorafenib | CAIX was neither prognostic nor predictive |

| Patel et al, 2008 | 43 | Tumour | HIF | Sunitinib | High HIF1α or HIF2α tumours more likely to respond |

| Xu et al, 2011 | 397 | Host | Angiogenesis and exposure-related genes | Pazopanib | Polymorphisms in IL-8, HIF1A, NR1I2 and VEGFA were associated with outcomes |

| Kim et al, 2012 | 63 | Host | VEGF polymorphisms | Sunitinib | Combination of VEGF SNP 936 and VEGFR2 SNP 889 was associated with survival |

| Escudier et al, 2009; Pena et al, 2010 | 713 | Plasma | VEGF pathway | Sorafenib | VEGF, CAIX, TIMP-1, Ras and p21 prognostic for survival, but not predictive for benefit |

| Zurita et al, 2012 | 69 | Plasma | CAFs | Sorafenib±IFN | CAF signature (osteopontin, VEGF, CAIX, collagen IV, VEGF receptor-2 and TRAIL) correlated with better PFS from the combination, and another signature predicted for benefit from sorafenib alone |

| Deprimo et al, 2007 | 55 | Plasma | VEGF and PLGF pathways | Sunitinib | Larger increases in VEGF, sVEGFR-2, and decreases in sVEGFR-3 in responding patients |

| Rini et al, 2008 | 61 | Plasma | VEGF pathway | sunitinib | Baseline sVEGFR-3 and VEGF-C below median were associated with better outcomes |

| Hutson et al, 2008 | 78 | Plasma, Tumour tissue | VEGF pathway, CECs and tumour VHL | Pazopanib | Tumour response correlated with decrease in sVEGFR2, but not with VHL status or other markers |

| Cho et al, 2007 | 20 | Tumour | mTOR pathway | Temsirolimus | High pS6K significantly associated and high pAkt trending to be associated with response; no correlation of CAIX, PTEN or VHL status with regression |

| Figlin et al, 2009 | 416 | Tumour | PTEN and HIF-1α | Temsirolimus | No association with response |

| Armstrong et al, 2012 | 404 | Plasma | LDH | Temsirolimus | Survival was extended with baseline LDH >ULN vs ⩽ULN; also, a decline in LDH with therapy was prognostic |

Abbreviations: CAF=cytokine and angiogenic factor; CAIX=carbonic anhydrase IX; CEC=circulating endothelial cell; HIF=hypoxia-inducible factor; IFN=interferon; IL=interleukin; LDH=lactate dehydrogenase; PFS=progression-free survival; PLGF=placental growth factor; RR=response rate; SNP=single-nucleotide polymorphism; sVEGFR2=soluble VEGF receptor 2; TIMP=tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase; TRAIL=tumour necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand; ULN=upper limit of normal; VHL=Von Hippel Lindau; VEGF=vascular endothelial growth factor.

Mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors

Histological factors

Temsirolimus is considered by some to be the defacto conventional therapy for non-CC-RCC based on the substantial proportion of these patients enrolled in the phase III temsirolimus trial. Moreover, non-CC patients also appeared to have an unanticipated benefit relative to the CC-RCC patients in this trial (Hudes et al, 2007).

Tumour tissue factors

Tumour pS6 and pAkt expression may be promising predictive biomarkers for response to temsirolimus (Cho et al, 2007). In this study, paraffin-embedded tissue sections from 20 patients who had received temsirolimus underwent IHC for mediators or downstream molecules of the mTOR pathway (phosphorylated (p)-S6, pAkt and PTEN), CAIX and VHL mutational analysis. There was a positive association of pS6 expression (P=0.02) and a trend toward positive expression of pAkt (P=0.07) with response to temsirolimus. No patient without high expression of either pS6 or pAkt demonstrated tumour regression. There was no correlation of CAIX, PTEN or VHL status with regressions. Furthermore, analysis of tumour from patients treated with temsirolimus in the randomised phase III trial found no correlation between PTEN or HIF1α expression and outcomes (Figlin et al, 2009). In another study, the mTOR pathway was found to be activated in metastases with correlation between different components of this signalling cascade, but without PTEN deletion (Abou Youssif et al, 2011). Only cytoplasmic p-mTOR was independently prognostic and demonstrated concordance between primary and metastasis.

Plasma-based factors

Baseline serum LDH may be a potential pretreatment predictive biomarker for the benefits conferred by mTOR inhibitors in patients with poor-risk RCC (Armstrong et al, 2012). In this retrospective analysis of the phase III trial, among 140 patients with elevated LDH, survival was significantly improved with temsirolimus compared with IFN (6.9 vs 4.2 months, P<0.002). Conversely, among 264 patients with normal LDH, survival was not improved with temsirolimus compared with IFN (11.7 vs 10.4 months, P=0.514). Adjusting for known prognostic factors, the HR for death was 2.01 for patients with LDH >1 upper limit of normal (ULN) vs ⩽1 ULN (P<0.0001). Intriguingly, a decline in LDH with therapy was also prognostic for OS (P<0.0001).

Early toxicities as pharmacodynamic biomarkers for anti-tumour activity

Vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors

HTN appears to be a pharmacodynamic marker correlating with outcomes with sunitinib (Rini et al, 2011a). This retrospective analysis included pooled efficacy (n=544) and safety (n=4917) data from four studies evaluating sunitinib. Blood pressure (BP) was measured on days 1 and 28 of each 6-week cycle. Efficacy and toxicities were compared between patients with and without HTN (maximum systolic BP (SBP)⩾140 mm Hg or diastolic BP (DBP)⩾90 mm Hg). Patients with systolic HTN had better outcomes than those without HTN (RR: 54.8% vs 8.7% median PFS: 12.5 vs 2.5 months and OS: 30.9 vs 7.2 months). Similarly, HTN defined by DBP was also associated with improved outcomes. Rates of adverse events were similar with and without HTN defined by mean SBP, although hypertensive patients experienced more renal adverse events. Similarly, a retrospective analysis of a phase III trial (n=716) demonstrated that patients receiving bevacizumab who developed grade ⩾2 HTN had improved outcomes (Harzstark et al, 2010). On multivariable analysis, HTN at 2 months was an independent predictor of OS (HR 0.62, P=0.046). Moreover, in an 8-week landmark analysis of 230 patients, the efficacy of axitinib was associated with DBP ⩾90 mm Hg (Rini et al, 2011b). Prospective randomised phase II (NCT 00835978) comparison of the standard dose vs dose titration and escalation of axitinib to attain hypertension and enhance outcomes is ongoing (Table 3). One retrospective study of 770 patients from prospective trials suggested that hand-foot syndrome (HFS) may serve as a predictive biomarker of sunitinib efficacy. The 179 patients (23%) who developed any-grade HFS had significantly better response rate (55.6% vs 32.7%), PFS (14.3 vs 8.3 months), and OS (38.3 vs 18.9 months) compared with those who did not develop HFS (P<0.0001). In a multivariate analysis, sunitinib-associated HFS remained a significant independent predictor of OS even by time-dependent analysis (Michaelson et al, 2011).

Table 3. Ongoing trials developing predictive biomarkers in RCC.

| Trial | Agent | Phase of trial | Target accrual | Design of trial | Tissue being analysed | Biomarker |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT 01297244 | Tivozanib | II | 100 | Open-label non-randomised | Tumour and plasma | Tumour tissue: CD68, HIF1/HIF2, VEGF A, VEGF-B, VEGF-C, VEGF-D, HGF, CAIX, PLGF and transcriptional profiles Plasma: VEGF-A, VEGF-B, VEGF-C, VEGF-D, HGF, and PLGF levels, protein expression, metabolite patterns and PK studies |

| NCT 00835978 | Axitinib | II | 200 | Double-blinded randomised with or without dose titration | Plasma PK studies | HTN |

| NCT00827359 | Everolimus | II | NA | Open label non-randomised | Tumour | NA |

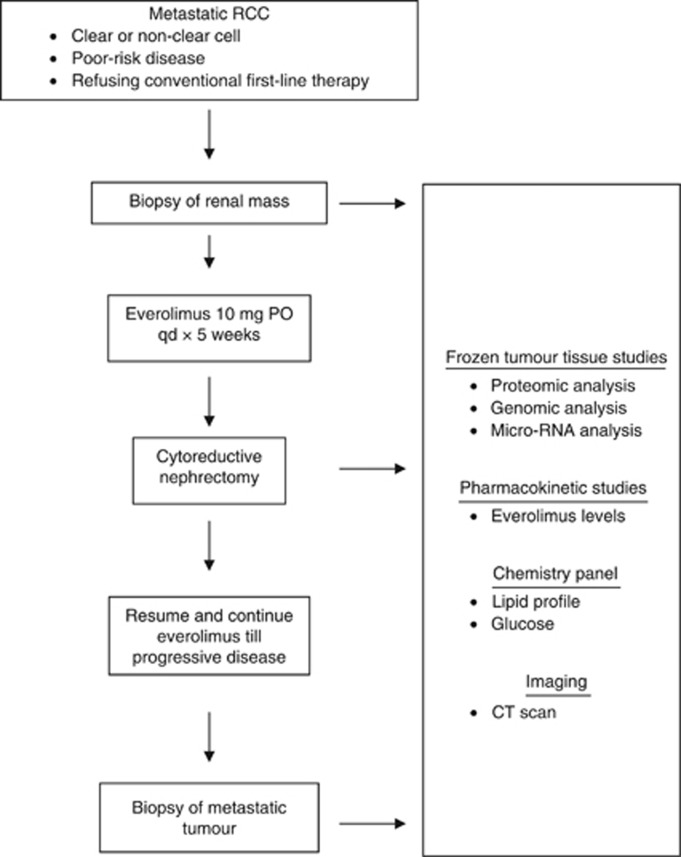

| NCT00831480 | Everolimus | II | 27 | Open label non-randomised with brief neoadjuvant therapy preceding CN | Tumour, plasma | Tumour tissue at baseline and post-therapy: proteomic and genomic studies, miRNA profiling, Plasma PK studies |

Abbreviations: CAIX=carbonic anhydrase IX; CN=cytoreductive nephrectomy; HGF=hepatocyte growth factor; HIF=hypoxia-inducible factor; HTN=hypertension; miRNA=micro RNA; NA=not applicable; PK=pharmacokinetic; PLGF=placental growth factor; VEGF=vascular endothelial growth factor.

The mTOR inhibitors

One retrospective study reviewed 44 patients metastatic RCC treated with temsirolimus or everolimus to investigate the association of drug-induced interstitial pneumonitis and outcomes (Dabydeen et al, 2011). Stable disease was achieved in 12 out of 14 patients (86%) who developed pneumonitis compared with 13 out of 30 (43%) without pneumonitis. Progressive disease (PD) was present in 1 out of 14 patients (7%) who developed pneumonitis compared with 16 out of 30 (53%) without pneumonitis. The mean change of tumour size by RECIST was −2.9% in the pneumonitis group and +4.13% in the non-pneumonitis group (P=0.005). In a retrospective analysis of the Global Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma phase III trial (416 evaluable patients), hypercholesterolaemia with temsirolimus was associated with prolonged survival (HR 0.77 per mmol l−1, P<0.0001), whereas the effect on triglycerides or glucose was not associated with survival (Lee et al, 2012a). However, biomarkers reliant on early changes are inherently less useful than biomarkers present at baseline (because baseline markers do not warrant the initiation of therapy, sometimes associated with expense and toxicities, before measurement).

Functional imaging

The mTOR inhibitors decrease glucose uptake and may be expected to downregulate fluoro-deoxy-glucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) uptake. However, one study suggested that FDG-PET uptake correlated with pAkt expression but did not predict mTOR inhibitor activity (Ma et al, 2009). Unfortunately, a phase II trial evaluating early FDG-PET changes to predict benefit from second-line everolimus could detect only a modest association with tumour regressions (Chen et al, 2011). In patients receiving sunitinib, baseline high FDG PET uptake and increased number of positive lesions appeared to yield prognostic information. Additionally, PET-computerised tomography progression at 16 weeks was associated with poor survival (Katani et al, 2011). Changes in vascular perfusion as imaged by dynamic contrast enhanced (DCE)-magnetic resonance imaging parameters after 4 weeks of sorafenib were not predictive for outcomes and were characterised by high variability and low magnitude of effect (Hahn et al, 2008). Another small study suggested that DCE-ultrasound changes may facilitate the prediction of efficacy of sunitinib (Lassau et al, 2010).

Future directions and challenges when developing biomarkers

Hypothetically, agents should probably be developed in molecularly enriched subsets likely to benefit across different tumours rather than in trials dedicated to morphological tumour subtypes. The therapeutic landscape for metastatic CC-RCC has witnessed the addition of a large number of VEGF and mTOR inhibitors. However, the critical determinants of response to each of these agents, which have slightly differing molecular targets and potencies, are unclear. Paradoxically, the rapid pace of expansion of the therapeutic armamentarium and commercial availability of multiple agents has hampered the development of predictive biomarkers. Moreover, the discovery studies performed heretofore are limited by small sample sizes and heterogeneous populations. Hence, large multicenter data sets are necessary to discover potential biomarkers. Notably, a 16-gene panel remained significantly associated with recurrence-free interval independent of clinical and pathological factors (necrosis, grade, stage, tumour size and lymph node involvement) in a study of 931 patients with localised RCC following nephrectomy (Rini et al, 2010). Lower recurrence was observed for angiogenesis (EMCN and NOS3) and immune-related (including CCL5 and CXCL9) genes. Thus, with further validation in the setting of randomised phase III trials, molecular biomarkers may assist in selection of high-risk patients likely to benefit from adjuvant therapy. Thereafter, in addition to carefully validating selected candidate genomic and proteomic biomarkers, metabolomic and micro-RNA profiling also need study. In conjunction with these efforts, standardisation of tissue sample acquisition, storage and analysis are imperative to enhance reproducibility and enable generalisability (Di Napoli and Signoretti, 2009). This problem is illustrated by the challenges still being encountered after years and even decades of clinical use of biomarkers in other settings, for example, IHC for Her2 and oestrogen receptor to guide breast cancer therapy.

A combination of clinicopathological and molecular factors may optimise patient selection for specific agents. More specifically, the molecular profile should provide a clinically meaningful increment in predictive performance over conventional clinical factors. The development of such predictive models may be complicated by the differing utility of specific molecular biomarkers based on the clinical risk group and specific agent being considered (Vickers et al, 2008). Despite the challenges and complexities, the predictive model should be characterised by optimal performance and be user-friendly to enable its employment at the bedside. Given the moderate increment in median PFS with the available VEGF and mTOR inhibitors, the vast majority of patients (70–80%) benefit to some extent, whereas a minority (20–30%) of patients have primary refractory disease. Thus, it may be important to prioritise biomarker development to initially identify baseline biomarkers for resistance in order to avoid subjecting those with primary refractory disease to futile and potentially toxic therapy. Multiple trials are attempting to combine bevacizumab with mTOR inhibitors, which may warrant the incorporation of biomarkers to identify subsets that preferentially benefit. The utility of biomarkers may be even more important in the setting of combinations, which may yield greater toxicities than single agents. Incorporation of biomarkers in the early development of novel agents in clinical trials is important to guide late-phase development, for example, tumour B7-H1 expression may be associated with response to PD-1-inhibiting agents to bolster the anti-tumour immune response, as suggested by a phase I trial (Brahmer et al, 2010).

A major challenge when developing personalised therapy is intratumor heterogeneity, which is underestimated by single tumour-biopsy samples. Molecular heterogeneity may promote adaptation and hinder personalised medicine as demonstrated in a recent study (Gerlinger et al, 2012). This study examined this issue by performing IHC, exome sequencing, chromosome aberration analysis and ploidy profiling on multiple spatially separated samples obtained from primary renal carcinomas and associated metastatic sites. Analysis revealed that 63–69% of all somatic mutations (including mTOR) were not detectable across every tumour region. Interestingly, gene-expression signatures of good and poor prognosis were detected in separate regions of the same tumour.

The neoadjuvant paradigm may assist in expediting the development of predictive biomarkers. In one trial of patients receiving bevacizumab plus erlotinib (n=23) or bevacizumab alone (n=27) for 8 weeks, frozen nephrectomy tumour specimens were subjected to correlative studies and compared with untreated controls (Jonasch et al, 2009). High tumour total AMPK (which regulates the PI3K pathway) and low PI3K pathway expression (low pAkt, low pS6K, high PTEN) correlated with longer survival, which may be a candidate pathway that interacts with the VEGF pathway and is a potential resistance mechanism. However, it is unclear if this tumour tissue profile is present at baseline or is induced by bevacizumab. An ongoing phase II trial (NCT00831480) is evaluating frontline everolimus administered before CN for metastatic RCC (Table 3, Figure 2). Patients undergo a baseline biopsy of the renal tumour followed by 3–5 weeks of everolimus before CN. Following surgery, everolimus is resumed and continued until progression or intolerable toxicity. Modulation of the mTOR signalling pathway and downstream proliferation, apoptosis and angiogenesis in the nephrectomy tumour specimen will be correlated with time to progression. Potentially, baseline markers as well as biological alterations in the tumour with brief therapy during a window of opportunity may predict long-term outcomes. However, this paradigm will only be applicable to patients presenting with metastatic disease who have not undergone prior nephrectomy. Brief neoadjuvant therapy evaluating highly tolerable novel agents before excision of localised high-risk RCC may also be worthy of utilisation to obtain signals of biological activity and develop predictive biomarkers. Moreover, functional imaging of tumour proliferation, metabolic pathways and vascular perfusion requires a commitment to prospective evaluation and validation.

Figure 2.

Design of phase II trial of neoadjuvant frontline everolimus preceding cytoreductive nephrectomy for metastatic RCC.

Conclusions

Renal cell carcinoma is not one disease but comprises a spectrum of subtypes based on different molecular drivers and host genetic backgrounds. Predictive biomarkers are in their infancy of development, but should be a priority in early preclinical and clinical development in order to guide rational tailored development of emerging agents. Multiple early prospective efforts to study biomarkers are ongoing (Table 3). The current economic climate demands a more focused development of new agents in populations likely to enjoy larger increments in outcomes than currently observed in unselected populations. Rational delivery of therapeutic agents is intimately coupled with molecular biomarkers in the contexts of breast cancer (Her2 predictive for benefit from Her2 inhibitors, Recurrence Score (Oncotype-DX, Genomic Health, Redwood City, CA, USA) predictive for benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy in oestrogen receptor-amplified breast cancer), colorectal cancer (K-ras wild type predictive for benefit from EGFR-inhibiting monoclonal antibodies), melanomas (V600E Raf kinase mutation predictive for benefit from Raf kinase inhibitors) and non-small cell lung cancer (EML4-ALK translocations or EGFR mutations to predict benefit from ALK and EGFR inhibitors, respectively). Hopefully, the rational selection of agents for the therapy of RCC will also take a step in this direction.

Footnotes

Guru Sonpavde received Research support from Novartis, Pfizer, and is speaker or advisory board for Novartis, Pfizer, GSK. Toni K Choueiri recieved Research support from Pfizer and is advisory board for Pfizer, Novartis, Aveo, GSK, Bayer/Onyx, Genentech, but not the speakers bureau.

References

- Abou Youssif T, Fahmy MA, Koumakpayi IH, Ayala F, Al Marzooqi S, Chen G, Tamboli P, Squire J, Tanguay S, Sircar K (2011) The mammalian target of rapamycin pathway is widely activated without PTEN deletion in renal cell carcinoma metastases. Cancer 117: 290–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong AJ, George DJ, Halabi S (2012) Serum lactate dehydrogenase predicts for overall survival benefit in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with inhibition of mammalian target of rapamycin. J Clin Oncol; e-pub ahead of print 13 August 2012 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Atkins M, Regan M, McDermott D, Mier J, Stanbridge E, Youmans A, Febbo P, Upton M, Lechpammer M, Signoretti S (2005) Carbonic anhydrase IX expression predicts outcome of interleukin 2 therapy for renal cancer. Clin Cancer Res 11: 3714–3721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergers G, Hanahan D (2008) Modes of resistance to anti-angiogenic therapy. Nat Rev Cancer 8: 592–603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brahmer JR, Drake CG, Wollner I, Powderly JD, Picus J, Sharfman WH, Stankevich E, Pons A, Salay TM, McMiller TL, Gilson MM, Wang C, Selby M, Taube JM, Anders R, Chen L, Korman AJ, Pardoll DM, Lowy I, Topalian SL (2010) Phase I study of single-agent anti-programmed death-1 (MDX-1106) in refractory solid tumors: safety, clinical activity, pharmacodynamics, and immunologic correlates. J Clin Oncol 28: 3167–3175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brannon AR, Reddy A, Seiler M, Arreola A, Moore DT, Pruthi RS, Wallen EM, Nielsen ME, Liu H, Nathanson KL, Ljungberg B, Zhao H, Brooks JD, Ganesan S, Bhanot G, Rathmell WK (2010) Molecular stratification of clear cell renal cell carcinoma by consensus clustering reveals distinct subtypes and survival patterns. Genes Cancer 1: 152–163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JL, Appelbaum DE, Kocherginsky Rathmell K, McDermott DF, Stadler WM (2011) FDG-PET as a predictive marker for therapy with everolimus in metastatic renal cell cancer. J Clin Oncol 29, (suppl; abstr e15047) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho D, Signoretti S, Dabora S, Regan M, Seeley A, Mariotti M, Youmans A, Polivy A, Mandato L, McDermott D, Stanbridge E, Atkins M (2007) Potential histologic and molecular predictors of response to temsirolimus in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. Clin Genitourin Cancer 5: 379–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choueiri TK, Plantade A, Elson P, Negrier S, Ravaud A, Oudard S, Zhou M, Rini BI, Bukowski RM, Escudier B (2008a) Efficacy of sunitinib and sorafenib in metastatic papillary and chromophobe renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 26: 127–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choueiri TK, Regan MM, Rosenberg JE, Oh WK, Clement J, Amato AM, McDermott D, Cho DC, Atkins MB, Signoretti S (2010) Carbonic anhydrase IX and pathological features as predictors of outcome in patients with metastatic clear-cell renal cell carcinoma receiving vascular endothelial growth factor-targeted therapy. BJU Int 106: 772–778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choueiri TK, Vaziri SA, Jaeger E, Elson P, Wood L, Bhalla IP, Small EJ, Weinberg V, Sein N, Simko J, Golshayan AR, Sercia L, Zhou M, Waldman FM, Rini BI, Bukowski RM, Ganapathi R (2008b) Von Hippel-Lindau gene status and response to vascular endothelial growth factor targeted therapy for metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma. J Urol 180: 860–865. discussion 865-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabydeen DA, Jagannathan JP, Ramaiya NH, Krajewski KM, Schutz F, Cho DC, Pedrosa I, Choueiri TK (2011) Pneumonitis associated with mTOR therapy in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: incidence, radiographic findings, and correlation with clinical outcome. J Clin Oncol 29 (suppl; abstr e15176) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deprimo SE, Bello CL, Smeraglia J, Baum CM, Spinella D, Rini BI, Michaelson MD, Motzer RJ (2007) Circulating protein biomarkers of pharmacodynamic activity of sunitinib in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: modulation of VEGF and VEGF-related proteins. J Transl Med 5: 32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Napoli A, Signoretti S (2009) Tissue biomarkers in renal cell carcinoma: issues and solutions. Cancer 115: 2290–2297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escudier B, Eisen T, Stadler WM, Szczylik C, Oudard S, Staehler M, Negrier S, Chevreau C, Desai AA, Rolland F, Demkow T, Hutson TE, Gore M, Anderson S, Hofilena G, Shan M, Pena C, Lathia C, Bukowski RM (2009) Sorafenib for treatment of renal cell carcinoma: final efficacy and safety results of the phase III treatment approaches in renal cancer global evaluation trial. J Clin Oncol 27: 3312–3318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figlin RA, de Souza P, McDermott D, Dutcher JP, Berkenblit A, Thiele A, Krygowski M, Strahs A, Feingold J, Boni J, Hudes G (2009) Analysis of PTEN and HIF-1alpha and correlation with efficacy in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma treated with temsirolimus versus interferon-alpha. Cancer 115: 3651–3660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finke J, Ko J, Rini B, Rayman P, Ireland J, Cohen P (2011) MDSC as a mechanism of tumor escape from sunitinib mediated anti-angiogenic therapy. Int Immunopharmacol 11: 856–861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlinger M, Rowan AJ, Horswell S, Larkin J, Endesfelder D, Gronroos E, Martinez P, Matthews N, Stewart A, Tarpey P, Varela I, Phillimore B, Begum S, McDonald NQ, Butler A, Jones D, Raine K, Latimer C, Santos CR, Nohadani M, Eklund AC, Spencer-Dene B, Clark G, Pickering L, Stamp G, Gore M, Szallasi Z, Downward J, Futreal PA, Swanton C (2012) Intratumor heterogeneity and branched evolution revealed by multiregion sequencing. N Engl J Med 366: 883–892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golshayan AR, George S, Heng DY, Elson P, Wood LS, Mekhail TM, Garcia JA, Aydin H, Zhou M, Bukowski RM, Rini BI (2009) Metastatic sarcomatoid renal cell carcinoma treated with vascular endothelial growth factor-targeted therapy. J Clin Oncol 27: 235–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordan JD, Lal P, Dondeti VR, Letrero R, Parekh KN, Oquendo CE, Greenberg RA, Flaherty KT, Rathmell WK, Keith B, Simon MC, Nathanson KL (2008) HIF-alpha effects on c-Myc distinguish two subtypes of sporadic VHL-deficient clear cell renal carcinoma. Cancer Cell 14: 435–446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn OM, Yang C, Medved M, Karczmar G, Kistner E, Karrison T, Manchen E, Mitchell M, Ratain MJ, Stadler WM (2008) Dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging pharmacodynamic biomarker study of sorafenib in metastatic renal carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 26: 4572–4578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harzstark AL, Halabi S, Stadler WM et al (2010) Hypertension is associated with clinical outcome for patients(pts) with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (RCC) treated with interferon and bevacizumab on CALGB 90206. Genitourinary Cancer Symposium. (abstr 351)

- Heng DY, Xie W, Regan MM, Warren MA, Golshayan AR, Sahi C, Eigl BJ, Ruether JD, Cheng T, North S, Venner P, Knox JJ, Chi KN, Kollmannsberger C, McDermott DF, Oh WK, Atkins MB, Bukowski RM, Rini BI, Choueiri TK (2009) Prognostic factors for overall survival in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with vascular endothelial growth factor-targeted agents: results from a large, multicenter study. J Clin Oncol 27: 5794–5799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirata H, Hinoda Y, Kikuno N, Kawamoto K, Suehiro Y, Tanaka Y, Dahiya R (2007) MDM2 SNP309 polymorphism as risk factor for susceptibility and poor prognosis in renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 13: 4123–4129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang D, Ding Y, Zhou M, Rini BI, Petillo D, Qian CN, Kahnoski R, Futreal PA, Furge KA, Teh BT (2010) Interleukin-8 mediates resistance to antiangiogenic agent sunitinib in renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Res 70: 1063–1071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudes G, Carducci M, Tomczak P, Dutcher J, Figlin R, Kapoor A, Staroslawska E, Sosman J, McDermott D, Bodrogi I, Kovacevic Z, Lesovoy V, Schmidt-Wolf IG, Barbarash O, Gokmen E, O'Toole T, Lustgarten S, Moore L, Motzer RJ (2007) Temsirolimus, interferon alfa, or both for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 356: 2271–2281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutson TE, Davis I, Machiels JH, de Souza PL, Baker K, Bordogna W, Westlund R, Crofts T, Pandite L, Figlin RA (2008) Biomarker analysis and final efficacy and safety results of a phase II renal cell carcinoma trial with pazopanib (GW786034), a multi-kinase angiogenesis inhibitor. J Clin Oncol 26: 5046 [Google Scholar]

- Hutson TE, Davis ID, Machiels JP, De Souza PL, Rottey S, Hong BF, Epstein RJ, Baker KL, McCann L, Crofts T, Pandite L, Figlin RA (2010) Efficacy and safety of pazopanib in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 28: 475–480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonasch E, Tsavachdidou D, Wood CG, Matin SF, Corn PG, Tamboli P, Wang X, Tannir N (2009) Phase II presurgical study of bevacizumab plus erlotinib in untreated patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 27: 15s (suppl; abstr 5004) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaelin WG (2008) The Von Hippel-Lindau tumour suppressor protein: O2 sensing and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 8: 865–873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katani I, Avril NE, Bomanji J, Chowdhury S, Rockall A, Sahdev A, Nathan P, Wilson P, Shamash J, Sharpe K, Lim L, Dickson J, Ell P, Reynolds AR, Powles T (2011) Sequential FDG-PET/CT as a biomarker of response to sunitinib in metastatic clear cell renal cancer. Clin Cancer Res 17: 6021–6028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai Y, Sakano S, Korenaga Y, Eguchi S, Naito K (2007) Associations of single nucleotide polymorphisms in the vascular endothelial growth factor gene with the characteristics and prognosis of renal cell carcinomas. Eur Urol 52: 1147–1155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JJ, Vaziri SA, Rini BI, Elson P, Garcia JA, Wirka R, Dreicer R, Ganapathi MK, Ganapathi R (2012) Association of VEGF and VEGFR2 single nucleotide polymorphisms with hypertension and clinical outcome in metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma patients treated with sunitinib. Cancer 118: 1946–1954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinrath T, Gassner C, Lackner P, Thurnher M, Ramoner R (2007) Interleukin-4 promoter polymorphisms: a genetic prognostic factor for survival in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 25: 845–851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lassau N, Koscielny S, Albiges L, Chami L, Benatsou B, Chebil M, Roche A, Escudier BJ (2010) Metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with sunitinib: early evaluation of treatment response using dynamic contrast-enhanced ultrasonography. Clin Cancer Res 16: 1216–1225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CK, Marschner I, Simes J, Voysey M, Egleston BL, Hudes G, de Souza PL (2012a) Increase in cholesterol predicts survival advantage in renal cell carcinoma patients treated with temsirolimus. Clin Cancer Res 18: 3188–3196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JL, Ahn JH, Lim HY, Park SH, Lee SH, Kim TM, Lee DH, Cho YM, Song C, Hong JH, Kim CS, Ahn H (2012b) Multicenter phase II study of sunitinib in patients with non-clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Ann Oncol 23: 2108–2114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibovich BC, Han KR, Bui MH, Pantuck AJ, Dorey FJ, Figlin RA, Belldegrun A (2003) Scoring algorithm to predict survival after nephrectomy and immunotherapy in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a stratification tool for prospective clinical trials. Cancer 98: 2566–2575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma WW, Jacene H, Song D, Vilardell F, Messersmith WA, Laheru D, Wahl R, Endres C, Jimeno A, Pomper MG, Hidalgo M (2009) [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography correlates with Akt pathway activity but is not predictive of clinical outcome during mTOR inhibitor therapy. J Clin Oncol 27: 2697–2704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDermott DF, Ghebremichael MS, Signoretti S, Margolin KA, Clark J, Sosman JA, Dutcher JP, Logan T, Figlin RA, Atkins MB (2010) The high-dose aldesleukin (HD IL-2) ‘SELECT’ trial in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 28: 15s (suppl; abstr 4514) [Google Scholar]

- Michaelson MD, Cohen DP, Li S, Motzer RJ, Escudier B, Barrios CH, Burnett PE, Puzanov I (2011) Hand-foot syndrome as a potential biomarker of efficacy in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with sunitinib. J Clin Oncol 29(suppl 7; abstract 320) [Google Scholar]

- Motzer RJ, Bacik J, Murphy BA, Russo P, Mazumdar M (2002) Interferon-alfa as a comparative treatment for clinical trials of new therapies against advanced renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 20: 289–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paez-Ribes M, Allen E, Hudock J, Takeda T, Okuyama H, Vinals F, Inoue M, Bergers G, Hanahan D, Casanovas O (2009) Antiangiogenic therapy elicits malignant progression of tumors to increased local invasion and distant metastasis. Cancer Cell 15: 220–231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel PH, Chadalavada RS, Ishill NM, Patil S, Reuter VE, Motzer RJ, Chaganti RS (2008) Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) 1a and 2a levels in cell lines and human tumor predicts response to sunitinib in renal cell carcinoma (RCC). J Clin Oncol 26: 15s (suppl; abstr 5008) [Google Scholar]

- Pena C, Lathia C, Shan M, Escudier B, Bukowski RM (2010) Biomarkers predicting outcome in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma: Results from sorafenib phase III Treatment Approaches in Renal Cancer Global Evaluation Trial. Clin Cancer Res 16: 4853–4863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porta C, Paglino C, De Amici M, Quaglini S, Sacchi L, Imarisio I, Canipari C (2010) Predictive value of baseline serum vascular endothelial growth factor and neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin in advanced kidney cancer patients receiving sunitinib. Kidney Int 77: 809–815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu AQ, Cheng S, Atkins MB, Signoretti S, Choueiri TK (2012) Carbonic anhydrase IX (CAIX) as a potential biomarker of efficacy in metastatic clear-cell renal cell carcinoma (mccRCC) in patients (pts) receiving sorafenib: Analysis of a randomized controlled trial (TARGET). J Clin Oncol 30 (suppl 5; abstr 352) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rini BI, Cohen DP, Lu DR, Chen I, Hariharan S, Gore ME, Figlin RA, Baum MS, Motzer RJ (2011a) Hypertension as a biomarker of efficacy in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with sunitinib. J Natl Cancer Inst 103: 763–773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rini BI, Michaelson MD, Rosenberg JE, Bukowski RM, Sosman JA, Stadler WM, Hutson TE, Margolin K, Harmon CS, DePrimo SE, Kim ST, Chen I, George DJ (2008) Antitumor activity and biomarker analysis of sunitinib in patients with bevacizumab-refractory metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 26: 3743–3748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rini BI, Zhou M, Schiller JH, Fruehauf JP, Cohen EE, Tarazi JC, Rosbrook B, Bair AH, Ricart AD, Olszanski AJ, Letrent KJ, Kim S, Rixe O (2011b) Diastolic blood pressure as a biomarker of axitinib efficacy in solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res 17: 3841–3849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rini BIZM, Aydin H, Elson P, Maddala T, Knezevic D, Parodi L, Bukowski RM, Novotny WF, Cowens JW (2010) Identification of prognostic genomic markers in patients with localized clear cell renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 28: 15s (suppl; abstr 4501) [Google Scholar]

- Schneider BP, Wang M, Radovich M, Sledge GW, Badve S, Thor A, Flockhart DA, Hancock B, Davidson N, Gralow J, Dickler M, Perez EA, Cobleigh M, Shenkier T, Edgerton S, Miller KD (2008) Association of vascular endothelial growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 genetic polymorphisms with outcome in a trial of paclitaxel compared with paclitaxel plus bevacizumab in advanced breast cancer: ECOG 2100. J Clin Oncol 26: 4672–4678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upton MP, Parker RA, Youmans A, McDermott DF, Atkins MB (2005) Histologic predictors of renal cell carcinoma response to interleukin-2-based therapy. J Immunother 28: 488–495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vickers AJ, Cronin AM, Elkin EB, Gonen M (2008) Extensions to decision curve analysis, a novel method for evaluating diagnostic tests, prediction models and molecular markers. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 8: 53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu CF, Bing NX, Ball HA, Rajagopalan D, Sternberg CN, Hutson TE, de Souza P, Xue ZG, McCann L, King KS, Ragone LJ, Whittaker JC, Spraggs CF, Cardon LR, Mooser VE, Pandite LN (2011) Pazopanib efficacy in renal cell carcinoma: evidence for predictive genetic markers in angiogenesis-related and exposure-related genes. J Clin Oncol 29: 2557–2564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zurita AJ, Jonasch E, Wang X, Khajavi M, Yan S, Du DZ, Xu L, Herynk MH, McKee KS, Tran HT, Logothetis CJ, Tannir NM, Heymach JV (2012) A cytokine and angiogenic factor (CAF) analysis in plasma for selection of sorafenib therapy in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Ann Oncol 23: 46–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]