Abstract

Background

Transfers of care have become increasingly frequent and complex with shorter inpatient stays and changes in work hour regulations. Potential hazards exist with transfers. There are few reports of institution-wide efforts to improve handoffs.

Methods

Our institution developed a hospital-wide physician handoff task force to proactively address issues surrounding handoffs and to ensure a consistent approach to handoffs across the institution.

Results

In this report, we discuss our experiences with handoff standardization, provider utilization of a new electronic medical record-based handoff tool, and implementation of an educational curriculum; our future work in developing hospital wide policies and procedures for transfers; and our consensus agreement on best methods for monitoring and evaluation of trainee handoffs.

Conclusion

The handoff task force infrastructure has enabled us to take an institution-wide approach to improving handoffs. The task force has improved patient care by addressing handoffs systematically and consistently and has helped create new strategies for minimizing risk in handoffs.

Keywords: Handoff, transition of care, sign-out, internship and residency, quality improvement

Background

In any setting, transfers of care among clinicians have the potential for error and adverse events.1–3 In large academic medical centers, the potential for error is even more acute. Decreasing length of stay, tighter work-hour restrictions for house staff, frequent changes in levels of care, and an expanding role of hospitalist physicians have made transfers in academic institutions more frequent, more complex, and potentially more dangerous.4 At the same time, accrediting organizations in the United States such as the Joint Commission and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) have become more vocal in advocating for standardization and improvements in handoff procedures.5,6

While numerous reports of interventions to improve intrahospital handoffs within specialties or units have been published, little has been written about attempts to standardize, formalize and coordinate handoffs across an entire institution. We developed an institution-wide hand off task force focused on licensed independent practitioners. Separate institutional efforts focused on nursing handoffs. This task force conducted a number of quality improvement activities to improve the quality of handoffs throughout the institution. Here we report on the barriers and facilitators we experienced in implementing a consistent hospital-wide approach to patient handoffs.

Local context and assessment of problems

Yale-New Haven Hospital is a 966-bed urban, academic medical center hosting over 80 training programs and 836 ACGME-accredited trainee positions. In 2007, when this initiative began, multiple conditions conspired to make handoffs a particularly high risk area. Mean length of stay was declining (from 5.46 days in 2002 to 5.18 days in 2007), while hospital admissions were rising (from 43,540 in 2002 to 51,431 in 2007), resulting in ever-increasing turnover of patients. Tighter ACGME regulations on resident work hours beginning in 2003 had increased the average daily number of transfers of care.4 Sign-out practices were variable among specialties, settings and teams. Studies of medicine house staff handoffs revealed deep-seated flaws in the sign-out process and a high rate of errors.7,8 In a Safety Attitudes Questionnaire9 completed by 4,721 nursing and medical staff in 2008, 56.8% of responses about handoffs and transitions were negative, indicating overall concern that handoffs and transitions were a safety gap at the institution.

Altogether, increased frequency of handoffs, variability in practice, and errors identified in internal assessments led both caregivers and institutional leadership to conclude that transfers of care were a major safety gap at our institution.

Results of assessment

In September, 2007, high level hospital administration convened a hospital-wide physician handoff task force to address system-wide problems with transfers of care. Each clinical department head was asked to nominate a front-line clinician to represent the department and to grant that person sufficient autonomy and resources to implement necessary changes.

The first hospital-wide physician handoff task force met in November, 2007 with representation from the largest specialties: medicine (both teaching and hospitalist services), general surgery, obstetrics and gynecology, pediatrics and emergency medicine. In addition, representatives from nursing and information technology were present. Over the next two years, the membership expanded to include representation from anesthesiology, neurosurgery, neurology, oncology, otolaryngology, psychiatry and medical education. The group has met on a monthly basis and been led by the task force chair (L.I.H.), whose research focus is handoffs.

The first meetings were devoted to process mapping of shift-to-shift handoffs within each specialty and to identifying major existing gaps. Some gaps were unique to individual specialties. For instance, process mapping in pediatrics revealed the on-call team had no dedicated pager and was therefore difficult for nurses to reach. This problem was rapidly solved by the purchase of a pager. More challenging situations were also uncovered: for instance, in the surgical service, the senior residents were often in the operating room at the time the junior house staff were transferring care to the night shift.

However, process mapping by LIPs in each specialty also revealed three gaps in handoffs that were common to all the different specialties: poor written documentation that was not always consistent with privacy regulations, lack of training and evaluation, and no standard policies. We determined that these three areas would therefore be most appropriate for the task force to focus on from a hospital-wide perspective. Our intention was to develop a consistent approach to documentation, training and policies across the whole institution. Initial efforts focused primarily on improving documentation, training and policies for shift-to-shift handoffs among primary team members (including house staff, physician assistants, nurse practitioners and attendings); however, many efforts had ancillary benefits for other types of handoffs such as those among consultants, at ends of rotations and between services.

Strategies for quality improvement/change

Standardization of written handoff documentation

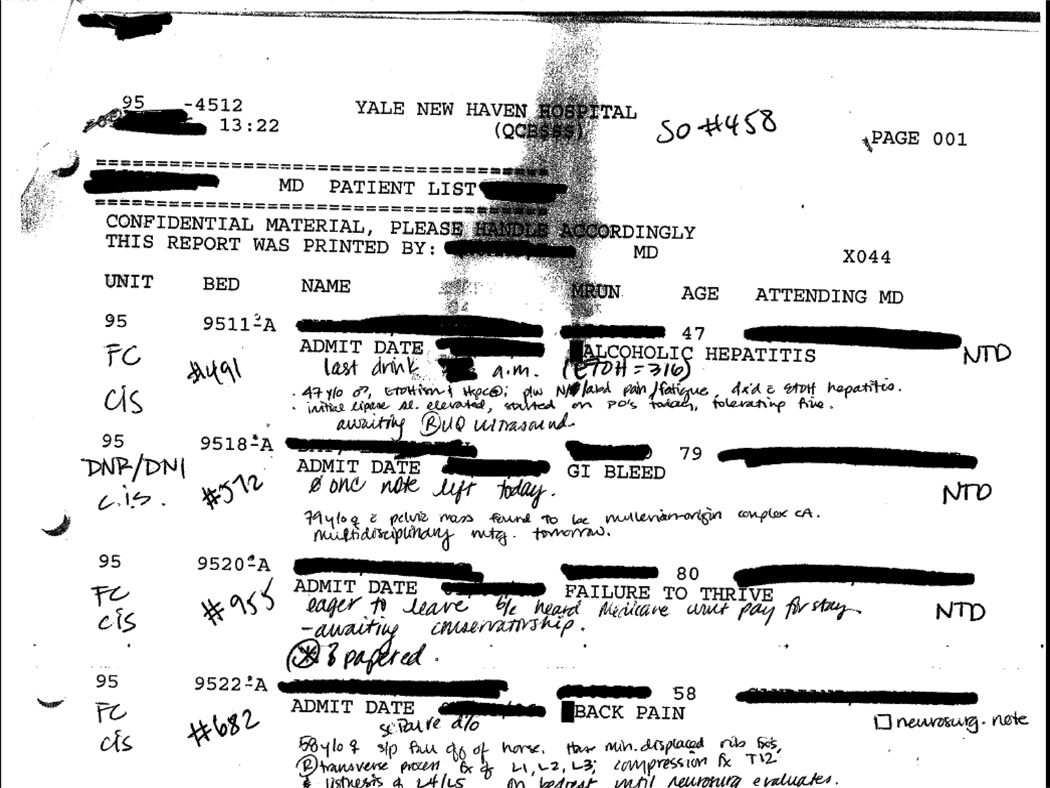

At the time the task force was created, the written sign-out was a potential hazard for all specialties. Clinicians were hand-writing sign-out notes (at times illegible or with minimal clinical information), using Word documents saved on local workstations, and saving Excel documents with patient information on memory sticks that were passed amongst physicians. There was no standardization, little ability to incorporate information from the electronic medical record, and a risk to patient confidentiality. (See Figure 1 for example of pre-existing written sign-out.)

Figure 1.

Example of medicine sign-out document, 2007

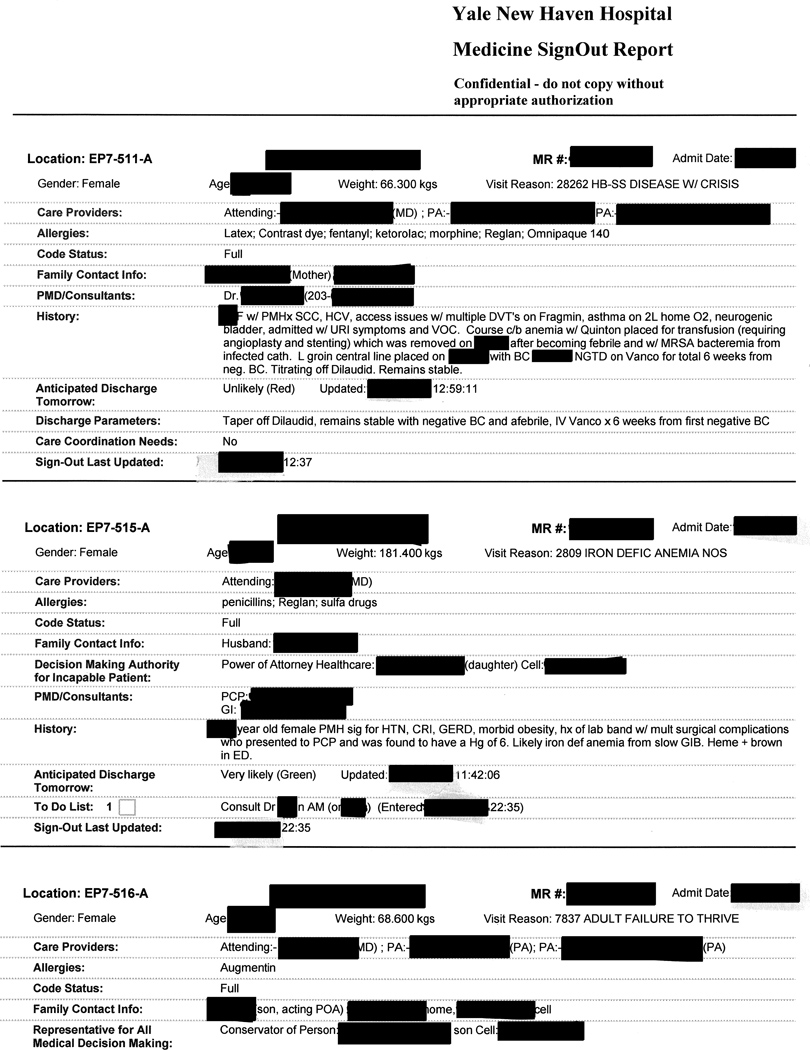

In the first six months, the task force developed and customized an institution-wide written sign-out tool. Based on our internally-developed mnemonic SIGNOUT [Sick/DNR, Identification, General hospital course, New events of the day, Overall clinical condition, Upcoming possibilities, and Tasks to do],10 we created a common format for all specialty sign-out notes that incorporated a few fields that were customized according to specialty. We used the opportunity of our hospital transitioning from paper notes to a fully integrated electronic medical record system (Sunrise Clinical Manager, Allscripts, Chicago, IL) to embed these electronic sign-out templates into the electronic medical record. For each patient’s hospital visit, specialty-specific sign-out documents could be created, edited at any time during the hospital stay from any clinical workstation, and read by any clinician with access to the medical record (see Appendix A for screenshots of the note template). Only one specialty-specific sign-out note could be created per patient per admission; however, multiple sign-out notes could be created by different specialties for the same patient, enabling consulting services to use a separate sign-out note for their handoffs. Any member of the care team could write and edit the sign-out note, including students, house staff, PAs and attendings. In practice, primary team sign-out notes were generally written by house staff or PAs, but were used by all members of the team including attendings. We created separate specialty sign-out notes for: gynecology, medicine, neurology, neurosurgery, obstetrics, pediatric surgery, pediatrics, psychiatry and surgery. A full list of sign-out elements is provided in Table 2. Although it was possible to access a single sign-out note for a particular patient, users more typically printed a report that collated all sign-out notes for the list of patients selected by the user into a more readable and compact format. (Figure 2) Patient lists are an intrinsic function of the EMR, can be created based on provider, team, specialty, location or other criteria, and are dynamic. Name, location, medical record number, age, gender, admission date, admission diagnosis, allergies and weight were among the fields automatically inserted into every sign-out report. Diet was added to all pediatric reports. Medications could be automatically imported and included in the printed report if desired by the end-user. This list was accurate as of the time of printing.

Table 2.

Information included in written sign-out

| Data field | Method of inclusion | Specialty |

|---|---|---|

| SIGNOUT mnemonic | Text at top of note template; not in printed report |

All |

| Location | Automatic feed from EMR | All |

| Name | Automatic feed from EMR | All |

| Medical record number | Automatic feed from EMR | All |

| Admission date | Automatic feed from EMR | All |

| Gender | Automatic feed from EMR | All |

| Age | Automatic feed from EMR | All |

| Weight | Automatic feed from EMR | All |

| Diet | Automatic feed from EMR | Pediatrics |

| Visit reason (as input by ED or registration) |

Automatic feed from EMR | All |

| Care providers | Manually select from list of providers assigned to patient including service, primary team, consulting team, attending, resident, intern, PA, care coordinator | All |

| Resident pager # | Manual entry | Neurology |

| Allergies | Automatic feed from EMR | All |

| Code status | Manual entry | All |

| Family contact info | Manual entry | All |

| Conservator status | Automatic feed from EMR | All |

| PMD/Consultants | Manual entry | All |

| History or Hospital course | Manual entry; option to insert text from progress note | All |

| Operations | Manual entry; option to insert text from progress note | Surgery |

| Procedure | Manual entry; option to insert text from progress note | Gynecology, obstetrics |

| Prenatal labs | Manual entry; option to insert text from progress note | Obstetrics |

| Oncology history | Manual entry; option to insert text from progress note | Gynecology |

| Medications | Automatic feed from EMR [optional] | All |

| Anticipated discharge date | Manual entry | All |

| Anticipated discharge tomorrow | Manual entry | All but obstetrics and gynecology |

| Discharge parameters | Manual entry | All but obstetrics and gynecology |

| Care coordination needs | Manual entry | All but obstetrics, gynecology and psychiatry |

| W10 [skilled nursing facility paperwork] |

Automatic feed from care coordinator note | All |

| To do list | Manual entry | All |

| Other notes | Manual entry; option to insert text from progress note | All but gynecology |

| Hgb, Hct, PT, PTT, Ca, ionized Ca, WBC, bilirubin, cyclosporin level, tacrolimus level |

Automatic feed from EMR | Surgery |

Major advantages of this new document over the sign-out mechanisms in place included: universal accessibility given access to a network or internet-connected computer; availability of the sign-out note to nurses, social workers, care coordinators, consultants and others not on the primary team; efficiency and error protection achieved by eliminating the need for repeated hand-copying; automatic updating of certain important elements; and potentially reduced risk of privacy violations. We did warn staff that the sign-out note was now considered part of the medical record for legal purposes.

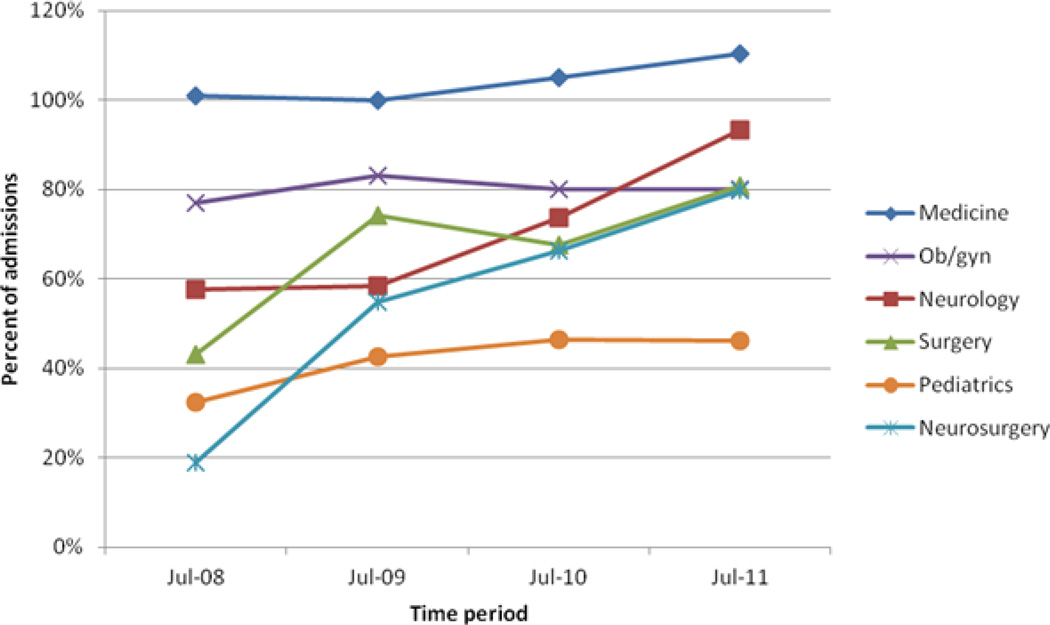

The written electronic sign-out was rolled out department by department with leadership by the representatives of the handoff task force, ensuring local buy-in and congruence with established workflow. By July, 2008 the electronic sign-outs were in institution-wide use. The task force monitored usage of the EMR-based written sign-out tool through periodic audits. Usage rose every year from a total of 3,002 sign-out notes created in July, 2008 to a total of 5,063 notes created in July, 2011. Figure 3 illustrates the proportion of admissions with an EMR-based sign-out note in July, 2008–2011 by specialty. For example, sign-out notes were created for every patient on the medicine service consistently in every year and even exceeded 100% because sign-out notes were written for patients admitted to “observation” status who are not counted as hospital admissions. Pediatrics had the lowest proportion of sign-out notes per admission; audits revealed that admissions without sign-out notes were predominantly well babies and newborn intensive care unit babies. The newborn intensive care unit continued to use its own separate sign-out system.

Figure 3.

Proportion of all July admissions from 2008–2011 with an EMR-based sign-out note created by the primary team. Rates exceed 100% in medicine because sign-out notes are created for observation patients as well as for inpatient admissions. Only the newborn special care unit creates sign-out notes outside the EMR.

Over the course of the 2008–2009 academic year, we devoted our efforts towards rapid-cycle feedback, modifying the written sign-out tool as necessary based on feedback from users. A full list of changes, their impact and remaining challenges is shown in Table 1. For instance, although the sign-out tool included a space to put date/time for a “to do” task overnight, these dates were uniformly omitted. Worse, clinicians sometimes failed to update the sign-out, leaving the same task apparently assigned on more than one night. We addressed this problem for medicine and surgery by adding automatic text to the printed sign-out report showing when the task field was last updated, and to the sign-out as a whole indicating last update date. In this way, even if a task was not removed, it would be immediately apparent to the reader that it was not current. Other specialties did not use the “to do” section. Although this feature was intended only to highlight outdated information, post-intervention audits revealed that sign-outs were routinely updated and outdated tasks were rare. Based on feedback from users, we added the capability to insert data into sign-out fields from fields in other notes to minimize the need for retyping or manual cut/paste. For example, specialties could elect to link the history section of the sign-out note to the assessment section of the progress note. Data was not automatically imported, but could be viewed and selected with minimal clicks. This feature was used in under half of sign-out note, depending on individual user preference and specialty culture. Pediatricians, for instance, routinely copied the entire assessment and plan into the sign-out note on a daily basis. Surgeons more often copied elements of the history from the initial history and physical when first creating a sign-out note and then updated the sign-out note separately each day.

Table 1.

Changes made to written sign-out after implementation

| Problem identified | Solution | Impact | Remaining challenge |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unclear when sign-out last updated | Date/time stamp added to printed sign-out report for each sign-out note | Percent of notes updated same day as of 7pm:* Gynecology: 50% Medicine: 89% Obstetrics: 90% Pediatrics: 83% Surgery: 70% Last updated more than 1 day prior to audit: Gynecology: 29% Medicine: 2% Obstetrics: 3% Pediatrics: 6% Surgery: 8% |

Which fields updated not apparent Continued use of relative time words such as “yesterday,” “tomorrow” |

| Out of date task lists | Date/time stamp added to each to do item | Percent of notes using “to do” section:* Medicine: 51% Surgery: 14% Pediatrics, obstetrics and gynecology: 0% Proportion of tasks ≤1 day old:* Medicine: 82% Surgery: 0% |

“To do” section not used consistently across specialties Tasks inconsistently updated |

| Desire for specific laboratory results by surgeons | Hgb, Hct, PT, PTT, Ca, ionized Ca, WBC, bilirubin, cyclosporin level, tacrolimus level automatically inserted into surgery sign-out notes | Not assessed | |

| Creating sign-out note time consuming | Ability to import progress note data into sign-out note | Proportion of notes linked to progress note:* Medicine: 46% Surgery: 14% Pediatrics: 43% Ob/gyn: 22% |

Purpose and format of progress note not aligned with sign-out note, limiting utility of this option |

| Proper paperwork not completed for discharge | Nursing agency paperwork flag added to sign-out notes | Not assessed | |

| Difficulty identifying patients likely to be discharged | “Likely discharge” field added to sign-out note, with date/time stamp | Year to date 2011 (tracked by service line and including updates from progress notes): Surgery 72% Medicine 85.5% Oncology 51.9% Psych 81.6% Pediatrics 73% Heart and Vascular 89.4% |

Lack of consistent update impaired patient identification; likely discharge field added to progress note as well to improve utilization |

| Patients in care of conservator inappropriately managed without involvement of conservator | Automatic conservator indicator added to sign-out note | Not assessed | |

| Patients admitted to observation status often not documented appropriately | Observation status flag added to printed sign-out report | Not assessed |

Data from 2012 audit of 514 charts, 456 sign-out notes

Data from 2011 audit of 88 charts, 74 sign-out notes

Several other modifications were made to the electronic written sign-out based on input from non-physicians. Because of the widespread physician use and easy accessibility by nursing staff and care-coordinators, the tool became recognized as a useful means of communicating across professional boundaries. At the request of care coordinators, we added a field to the sign-out that imported data from care coordination indicating patients who required specific paperwork to be completed prior to discharge. At the request of hospital administrators, we added a mandatory field indicating likelihood of next day discharge (green/likely, yellow/possible, red/unlikely). Each night, the unit staff used this field to identify patients planned for next day discharge, to prioritize workload and prepare paperwork accordingly. In combination with other workflow changes, this intervention was associated with an increase in the proportion of patient discharges before 11am from 12% in October, 2008 to 21% in fiscal year 2010–2011. Similar approaches have been successful at other institutions.11

Hospital-wide physician training

Once the hospital had a consistent and standardized written sign-out across the institution that was accessible by supervisors and educators, variation and inconsistency in handoff skills became more apparent. Review by the task force found that throughout the institution, handoff practices were “passed down” from resident to intern year by year, without formal training or evaluation. The task force determined that formal, standardized, consistent education and training should be implemented institution-wide.

Each member of the task force separately developed a specialty-specific standard framework for shift-to-shift handoffs that included information content that was expected to be conveyed in oral and written form. These standard protocols were included in specialty-specific training sessions. Task force members developed curricula for each specialty separately, but curricula were shared within the task force, ensuring that a common set of standards was taught throughout the institution. By the 2010–2011 academic year, every major specialty had implemented sign-out training for new house staff; these sessions are now a standard part of orientation or summer lectures.10 Sign-out training varies by specialty but typically includes a didactic lecture and, in medicine, practice sessions with observation and feedback from experienced clinicians. The sharing or cross-fertilization of teaching experiences has been valuable for many of these clinician-educators who rarely have the opportunity to meet other clinician-educators outside their field.

Handoff evaluation

As part of the ACGME Institutional Review Common Program Requirements Section VI, B., (effective July 1, 2011), all programs must create work assignments that minimize the number of transitions of care; programs must ensure and monitor structured handoff processes to facilitate continuity of care and patient safety; programs must ensure that the residents are competent in the handoff communication; and programs must ensure that the schedule of currently responsible attendings and resident for each patient’s care be available to all healthcare providers. Because of the competency component of the above requirement, programs and program directors welcomed the educational program developed by the committee chair and distributed and taught by the committee members.

In order to meet this requirement hospital-wide, the task force collected existing evaluation tools, reviewed internal standards for handoffs, and set institution-wide standards for evaluating trainee handoffs. Based on internal standards and existing evaluation tools,7,12–16 the task force developed evaluation forms for written and for oral handoffs, which were provided to every training program to standardize evaluation practices (Appendices B and C). These evaluation forms were deliberately designed to capture some of the persistent challenges we have found in sign-out quality, such as use of ambiguous time references and lack of clear “to do” lists. Some specialties, such as obstetrics, already had a formal mandate that attendings be present at every shift-to-shift handoff and provide real-time feedback on sign-out skills. For other specialties, the task force determined that involving the attending physician was more challenging. Consequently, the task force chair conducted two “train the trainer” sessions with program directors and chief residents throughout the institution in order to have a cadre of trained evaluators throughout the institution who could ensure high-quality handoffs consistent with institutional policies. Institution-wide evaluation practices will not be fully implemented until academic year 2012–2013 and have not yet been evaluated as to extent and efficacy.

Adverse event monitoring

In 2009, the task force took on the responsibility of reviewing all adverse events or near misses reported by staff related specifically to handoffs. There are typically 3–4 events noted every quarter. The task force has used the adverse event reports to track the efficacy of existing protocols, to identify gaps in care, and to prioritize future work. For example, a consistent trend of adverse event reports related to transfers between units or services has prompted the task force to begin shifting attention from shift-to-shift handoffs to handoffs between settings (i.e. intensive care unit to floor) or services (i.e. medicine to surgery).

Outcomes monitoring

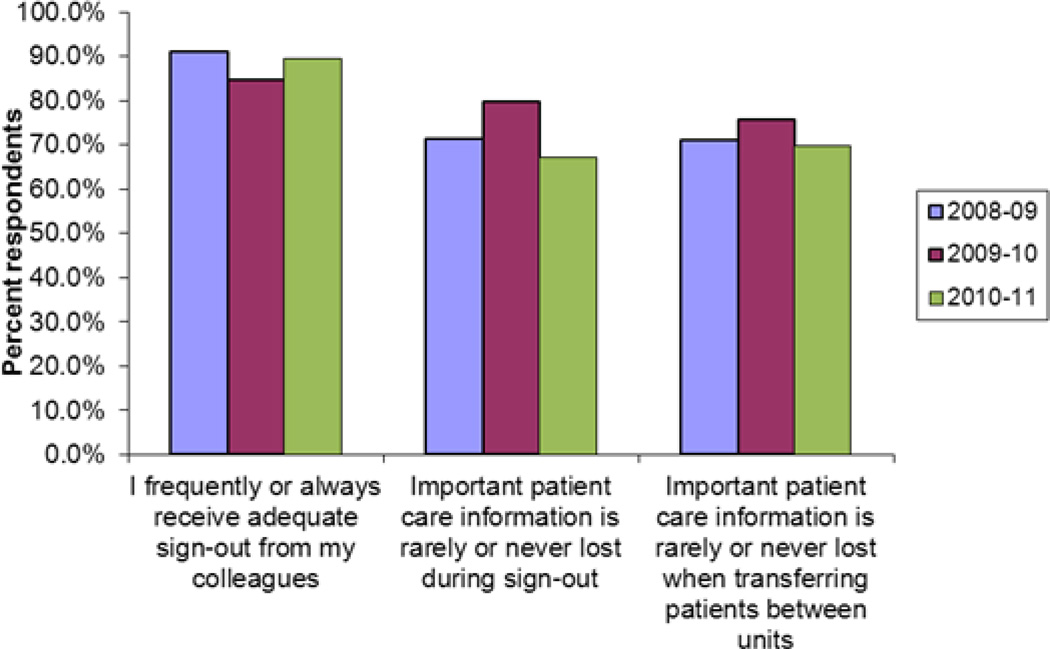

Since 2009 several questions about handoffs have been included in an annual end-of-year house staff and fellow survey conducted by the medical education office and sent to all resident and fellow trainees as part of routine internal evaluation processes. At the end of the 2008–2009 academic year (the first year of the written EMR-based sign-out), 210/624 (33.7%) of house staff responded to the handoff questions, in 2009–2010 247/633 (38.7%) responded and in 2010–2011 222/638 (34.6%) responded. Of respondents in 2008–09, 149/210 (71.3%) house staff reported that important care information was rarely or never lost during sign-out, and 190 (90.9%) reported that they frequently or always received adequate sign-out from their colleagues. Results in 2009–2010 and 2010–2011 were similar (Figure 4). There are several possible explanations for lack of improvement over time. First, we began evaluations only after the EMR-based handoff was in place; consequently, we are unable to determine whether perceptions were worse before interventions. Second, education and training may have raised awareness and expectations for high quality sign-out while potentially not improving skills to the same extent. Third, in most specialties uptake and usage of the EMR-based note was high early on and then sustained, leaving little room for improvement over time. Fourth, perceptions of sign-out adequacy are generally high, also leaving relatively little room for improvement. We will continue to track results as we implement more comprehensive evaluation and feedback programs.

Figure 4.

Percent of house staff responding in the affirmative to sign-out related questions in the annual end-of-year institutional house staff survey. Sign-out related questions are a subset of a larger survey.

Current Work

In addition to ongoing audits of written sign-out documentation, annual handoff training, adverse event reviews and formalizing evaluation methods, the task force has shifted its attention this year to two new areas.

First, a pending institution-wide transition to a new EMR has reignited the issue of written documentation for shift-to-shift handoffs. The new EMR will not be able to precisely replicate the existing written sign-out tool. Consequently, the task force has been working closely with the hospital information technology (IT) department and the new EMR vendor to design an effective and standardized institution-wide tool. The task force’s institution-wide authority, multi-specialty nature, experiences with building the previous EMR-based tool, and knowledge of workflow throughout the institution have been invaluable in ensuring both that the project is an institutional priority, and that the resulting tool will be usable and effective.

Second, the task force has begun interfacing with intensive care unit committees, bed management and hospital IT to address the perennial problem of transfers between settings. The multi-specialty nature of the task force ensures that multiple perspectives are considered, and that barriers and facilitators on part of the transferring party and receiving party are understood. We are currently in the process of developing policies regarding 1) which personnel must approve the handoff, 2) who is involved in the verbal handoff, and 3) standards for transfer orders and written handoffs. In addition, we are working with information technology on mechanisms to ensure that both transferring and receiving parties are aware of the handoff, and to build in safeguards to prevent patients from becoming “lost” in transition.

Lessons and Messages

Overall, the work of the task force appears to have been effective. Usage of the written sign-out report is nearly ubiquitous and has been sustained over several years despite minimal outreach and little enforcement of use (Figure 3). We believe this rapid and comprehensive uptake is a consequence of embedding the written sign-out in the electronic medical record, making it easy to use and a natural fit with existing workflow, and allowing multiple specialties to have their own sign-out note for the same patient. House staff throughout the institution have reported satisfaction with sign-out practices. Other reports of written sign-out documentation have shown similar levels of satisfaction and usage, although nearly all have been specialty-specific.17–23

Having a multi-specialty group responsible for handoffs throughout the hospital has been “more than the sum of its parts” for many reasons. First, the task force reports to the hospital’s Patient Safety and Quality Committee on a regular basis, thus formally establishing handoffs within the hospital’s patient safety structure, ensuring handoffs remain a priority for the institution, and enabling the group to advocate for necessary resources. Individual departments working on their own handoffs in isolation would be less visible and less powerful. Second, the task force has been an efficient means of coordinating responses to hospital-wide changes affecting handoffs, from new regulatory requirements to a new EMR build. Separate work by individual departments would likely be duplicative. Third, as a single voice for handoffs throughout the institution, the task force serves as a centralized resource for anyone interested in working on handoffs, including researchers, nurse committees working on nursing handoffs, and the Yale Medical Group, the physician corporation of Yale University, which in 2011 identified handoffs as a major outpatient physician risk. Fourth, the multi-specialty nature of the group has allowed us to learn from each other, adapt strategies undertaken in other areas, and pool ideas, tools and resources, improving the quality of handoffs hospital-wide.

Supplementary Material

Figure 2.

Example of new medicine sign-out report, medicine service, 2011. This example includes a mix of hospitalist and house staff team patients.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge other members of the handoff task force: Amanda McCabe, PA, Peter Marks, MD, Alicia Romeo, MD, Mert Bahtiyar, MD, and Leslie Hutchins. The authors would like to thank Connor Essick and Amy Schoenfeld for assistance with data collection.

Funding: Dr. Horwitz is supported by the National Institute on Aging (K08 AG038336) and by the American Federation for Aging Research through the Paul B. Beeson Career Development Award Program. Dr. Horwitz is also a Pepper Scholar with support from the Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center at Yale University School of Medicine (#P30AG021342 NIH/NIA). No funding source had any role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Aging, the National Institutes of Health or the American Federation for Aging Research.

Footnotes

Competing interests: No author has competing interests to report.

Contributorship statement: The ten authors are justifiably credited with authorship, according to the authorship criteria of ICMJE guidelines. Leora Horwitz: project management, conception, design, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, final approval given; all remaining nine authors: conception and design, critical revision of manuscript, final approval given. Dr. Horwitz serves as guarantor.

References

- 1.Ong MS, Coiera E. A systematic review of failures in handoff communication during intrahospital transfers. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2011;37:274–284. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(11)37035-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roy CL, Poon EG, Karson AS, Ladak-Merchant Z, Johnson RE, Maviglia SM, et al. Patient safety concerns arising from test results that return after hospital discharge. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:121–128. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-2-200507190-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moore C, Wisnivesky J, Williams S, McGinn T. Medical errors related to discontinuity of care from an inpatient to an outpatient setting. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:646–651. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20722.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Horwitz LI, Krumholz HM, Green ML, Huot SJ. Transfers of patient care between house staff on internal medicine wards: a national survey. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1173–1177. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.11.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Common Program Requirements. 2011 http://www.acgme-2010standards.org/pdf/Common_Program_Requirements_07012011.pdf.

- 6.Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. 2008 Critical Access Hospital and Hospital National Patient Safety Goals. 2008 http://www.jointcommission.org/PatientSafety/NationalPatientSafetyGoals/08_hap_npsgs.htm.

- 7.Horwitz LI, Moin T, Krumholz HM, Wang L, Bradley EH. Consequences of inadequate sign-out for patient care. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1755–1760. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.16.1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horwitz LI, Moin T, Krumholz HM, Wang L, Bradley EH. What are covering doctors told about their patients? Analysis of sign-out among internal medicine house staff. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18:248–255. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2008.028654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sexton JB, Helmreich RL, Neilands TB, Rowan K, Vella K, Boyden J, et al. The Safety Attitudes Questionnaire: psychometric properties, benchmarking data, and emerging research. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6:44. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-6-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horwitz LI, Moin T, Green ML. Development and implementation of an oral sign-out skills curriculum. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1470–1474. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0331-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oldfield P, Clarke E, Piruzza S, Holmes R, Paquette S, Dionne M, et al. Red light-green light: from kids' game to discharge tool. Healthc Q. 2011;14:77–81. doi: 10.12927/hcq.2011.22163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bump GM, Jovin F, Destefano L, Kirlin A, Moul A, Murray K, et al. Resident sign-out and patient hand-offs: opportunities for improvement. Teach Learn Med. 2011;23:105–111. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2011.561190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flanagan ME, Patterson ES, Frankel RM, Doebbeling BN. Evaluation of a Physician Informatics Tool to Improve Patient Handoffs. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2009;16:509–515. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farnan JM, Paro JA, Rodriguez RM, Reddy ST, Horwitz LI, Johnson JK, et al. Hand-off education and evaluation: piloting the observed simulated hand-off experience (OSHE) J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:129–134. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1170-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gakhar B, Spencer AL. Using direct observation, formal evaluation, and an interactive curriculum to improve the sign-out practices of internal medicine interns. Acad Med. 2010;85:1182–1188. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181da8370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pickering BW, Hurley K, Marsh B. Identification of patient information corruption in the intensive care unit: using a scoring tool to direct quality improvements in handover. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:2905–2912. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181a96267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bernstein JA, Imler DL, Sharek P, Longhurst CA. Improved physician work flow after integrating sign-out notes into the electronic medical record. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2010;36:72–78. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(10)36013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Palma JP, Sharek PJ, Longhurst CA. Impact of electronic medical record integration of a handoff tool on sign-out in a newborn intensive care unit. J Perinatol. 2011;31:311–317. doi: 10.1038/jp.2010.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nabors C, Peterson SJ, Lee WN, Mumtaz A, Shah T, Sule S, et al. Experience with faculty supervision of an electronic resident sign-out system. Am J Med. 2010;123:376–381. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Eaton EG, Horvath KD, Lober WB, Rossini AJ, Pellegrini CA. A randomized, controlled trial evaluating the impact of a computerized rounding and sign-out system on continuity of care and resident work hours. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;200:538–545. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ryan S, O'Riordan JM, Tierney S, Conlon KC, Ridgway PF. Impact of a new electronic handover system in surgery. Int J Surg. 2011;9:217–220. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Petersen LA, Orav EJ, Teich JM, O'Neil AC, Brennan TA. Using a computerized sign-out program to improve continuity of inpatient care and prevent adverse events. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 1998;24:77–87. doi: 10.1016/s1070-3241(16)30363-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kochendorfer KM, Morris LE, Kruse RL, Ge B, Mehr DR. Attending and resident physician perceptions of an EMR-generated rounding report for adult inpatient services. Family Medicine. 2010;42:343–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.