Abstract

EMBO J (2012) 31 19, 3833–3844 doi:; DOI: 10.1038/emboj.2012.217; published online September 07 2012

EMBO Rep (2012) 13 9, 840–846 doi:; DOI: 10.1038/embor.2012.105; published online September 07 2012

The ‘RING-between-RING’-type E3 ubiquitin ligase HOIP acts via a novel RING/HECT-hybrid ubiquitin transfer mechanism and catalyses the formation of linear ubiquitin chains by non-covalently binding the acceptor ubiquitin. But in the absence of a binding partner, HOIP is auto-inhibited. This explains why assembly of either HOIP/HOIL-1L or HOIP/SHARPIN is required to catalyse linear chain formation.

Post-translational modification of a protein with Ubiquitin (Ub) requires the activity of three enzymes: a Ub activating enzyme (E1), a Ub conjugating enzyme (E2), and a Ub ligase (E3). Final Ub transfer is performed by an E3 enzyme, which mediates the ligation of Ub from an E2∼Ub conjugate (‘∼’ denotes a thioester) onto a substrate. E3s are commonly divided into two mechanistic classes: RING/U-box E3s and HECT E3s. RING/U-box E3s facilitate the transfer of Ub from the E2∼Ub directly onto a substrate amino group. In contrast, HECTs transfer Ub from the E2∼Ub to the substrate via a HECT∼Ub intermediate. This mechanistic difference leads to an important distinction regarding what determines the type of Ub product (i.e., the specific Ub-chain linkage) formed: in ubiquitination pathways involving RING-type E3 ligases, the E2 determines the product formed, whereas for HECT-catalysed pathways, the E3 governs product formation (Christensen et al, 2007; Kim and Huibregtse, 2009).

RING-between-RING (RBR) E3s comprise a class of E3s that appear to have special properties. Although RBR E3s have been considered as a subfamily of RING E3s, the RBR E3 HHARI (Human Homologue of ARIadne) was recently shown to form a HECT-like E3∼Ub intermediate (Wenzel et al, 2011). Two other members of the RBR family, HOIL-1 and HOIP, form the Linear Ub Chain Assembly Complex (LUBAC), the only E3 ligase known to catalyse the synthesis of linear Ub chains (Kirisako et al, 2006). Linear Ub chains are produced by head-to-tail conjugation of Ub molecules through their N- and C-termini and have been shown to activate the canonical NF-κB pathway (Tokunaga et al, 2009).

Two studies by the Rittinger and Sixma groups now reveal important insights regarding the formation of linear Ub chains by the dimeric RBR E3 complex HOIP/HOIL-1L (Smit et al, 2012; Stieglitz et al, 2012). Results from these studies highlight three emerging themes among RBR ligases: a RING/HECT-hybrid Ub transfer mechanism; auto-inhibition of RBR E3 activity, and a role for E3:Ub interactions.

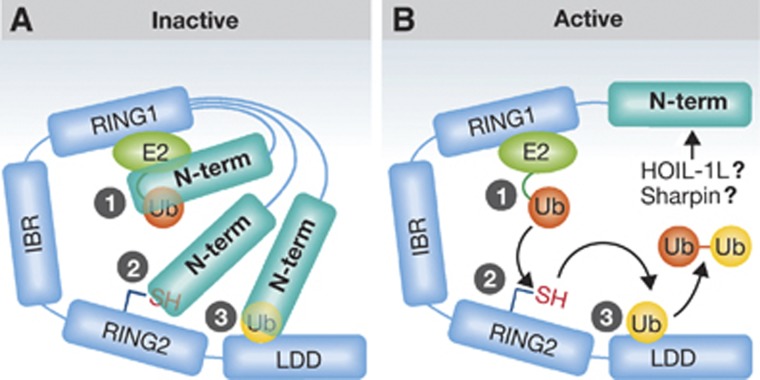

The RBR E3 ligase domain consists of two distinct RING domains, called RING1 and RING2, connected by an IBR (In-Between-Ring) domain. Despite its name, RING2 is not a canonical RING domain as it contains an active site Cysteine (Cys), which has recently been shown to form a thioester E3∼Ub intermediate, as directly detected for the RBR E3 HHARI. Although the Ub-loaded species could not be detected for the RBR E3 parkin, mutation of the analogous cysteine residue abrogated parkin’s ligase activity implying that it works via the same mechanism. On the basis of these observations, Wenzel et al (2011) proposed that the RBR E3s are a family of RING/HECT hybrids that use RING1 to bind an E2 (RING-like) and RING2 to present the active site Cys (HECT-like) as shown schematically in Figure 1. Both Smit et al (2012) and Stieglitz et al (2012) observed a HOIP∼Ub thioester, confirming that HOIP also acts via a RING/HECT-hybrid mechanism. Furthermore, Smit et al (2012) used a clever strategy to uncouple the first transfer event (E2∼Ub to E3) from the final transfer event (E3∼Ub to substrate Ub) to verify that the E3∼Ub intermediate is a prerequisite for Ub transfer onto a substrate and not just a serendipitous side product. The results extend the number of RBR E3s for which a thioester intermediate has been observed and support the notion that RBR E3s are indeed RING/HECT hybrids.

Figure 1.

Three common themes are emerging among RBR ligases: a RING/HECT-hybrid Ub transfer mechanism; auto-inhibition of RBR E3 activity, and a role for E3:Ub interactions. RBR E3s are characterized by their RBR domain that consists of two distinct RING domains, RING1 that binds the E2, and RING2 that harbours the active site Cys. Two new studies on the RBR E3 HOIP show that (a) domain(s) in HOIP’s N-terminal region inhibits its ligase activity and (b) a domain C-terminal to HOIP’s RBR binds and orients an acceptor Ub to direct linear Ub-chain formation (‘Linear Ub chain Determining Domain’ or LDD). (A)Three ways in which auto-inhibition might occur are illustrated: (1) inhibition of E2∼Ub binding by RING1, (2) obstruction of the active site cysteine on RING2, and/or (3) occlusion of acceptor Ub binding on the LDD. (B) A possible flow of events that occur once auto-inhibition released is shown. Details of each step and how specifically auto-inhibition is released are still unknown.

Previous studies have established that HOIP Ub ligase activity and subsequent activation of NF-κB require either the RBR-containing protein, HOIL-1L, or SHARPIN, an adaptor protein associated with LUBAC (Ikeda et al, 2011; Tokunaga et al, 2011). The two current studies now show that although full-length HOIP exhibits very low activity on its own, removal of the N-terminal ∼700 residues results in robust ligase activity. Thus, HOIP appears to be auto-inhibited in the absence of a binding partner. Further analysis revealed that HOIP’s UBA (Ub-Associated) domain is partly responsible for auto-inhibition, although additional N-terminal domains appear to have auto-inhibitory effects as well. SHARPIN, which contains a UBL (Ub-Like) domain, can relieve auto-inhibition of HOIP. Similarly, the addition of the HOIL-1L UBL domain, previously shown to interact with the HOIP UBA domain (Yagi et al, 2012), relieves inhibition. Interestingly, the addition of full-length HOIL-1L results in even greater ubiquitination activity.

Stieglitz et al (2012) show that the RBR E3 HOIL-1L has very low E3 activity on its own. Intriguingly, they found that mutation of the HOIL-1L RING2 active site Cys (C460A) reduced activity of the HOIP/HOIL-1L complex back to levels comparable to HOIP activity in presence of HOIL UBL alone. This suggests a more active, catalytic role for HOIL-1L in linear Ub-chain formation than previously appreciated. The details regarding this role must await further studies, but involvement of an active site Cys residue on a second RING2 domain suggests a possible reciprocal transfer mechanism. Perhaps linear chains can be pre-built via such a mechanism and passed en bloc to substrate, similarly to mechanisms used by some HECT-type bacterial E3 ligases (Levin et al, 2010).

Parkin, another RBR E3, also exhibits auto-inhibition (Chaugule et al, 2011), but the auto-inhibitory mechanism and the release thereof differ from HOIP. Unlike parkin’s N-terminal UBL, which is thought to interact within the RBR domain at RING2, HOIP’s UBA does not bind detectably in trans to any region in the RBR domain (Stieglitz et al, 2012). Furthermore, addition of its UBA in trans does not inhibit the activity of HOIP RBR E3 as was seen with parkin and its UBL domain. The auto-inhibition of parkin is likely released by substrate binding, because addition of either the UIM of Eps15 or the SH3 domain of endophilin-A, both known to bind the parkin UBL, can restore the activity of parkin (Chaugule et al, 2011). In addition, phosphorylation of Ser65 within the UBL of parkin by PINK-1 activates parkin, presumably by releasing the UBL from RING2 (Kondapalli et al, 2012). In contrast, HOIP overcomes its auto-inhibition through binding either HOIL-1L or SHARPIN. There is no additive effect when both binding partners are present, consistent with the notion that both proteins act via their UBL domains, although this remains to be demonstrated for SHARPIN. The activity of either SHARPIN/HOIP or HOIL-1L/HOIP can activate NF-κB (Ikeda et al, 2011; Tokunaga et al, 2011), but how the protein complexes differ in their cellular roles remains to be further analysed.

The finding that HOIP and parkin exhibit auto-inhibition raises the question whether there is something special about the RBR E3s that require auto-inhibition. In this regard, we note that RBR E3s bind the E2 UbcH7 with significantly tighter affinity than canonical RING E3s bind their E2s (Dove and Klevit, unpublished). In the absence of a substrate, RING1 loaded with UbcH7∼Ub would lead to non-productive transfer of Ub from UbcH7∼Ub to the active site of RING2. Occlusion of the active site by auto-inhibition may therefore act as a safety check until its activity is required for transfer of Ub to a substrate. As yet, there is no evidence to indicate whether substrate binding will release HOIP auto-inhibition, as it does for parkin, but this remains a possibility.

The revelation that removal of all domains N-terminal to the HOIP RING1 domain yields a highly active ligase allowed both groups to explore questions pertaining to how linear chains are built. Remarkably, constructs comprised of only the RBR domain through the C-terminus of HOIP are sufficient to specify linear Ub chains. (The two groups use HOIP constructs that differ by only two N-terminal residues (697/699–1072) but Stieglitz et al call their construct RBR whereas Smit et al call it RBR-LDD.) (Smit et al, 2012; Stieglitz et al, 2012). Smit et al (2012) demonstrate that the region immediately C-terminal to RING2 is required for linear chain building activity and name the region the ‘LDD’ (Linear Ub chain Determining Domain). Their results indicate that the LDD binds and orients the acceptor Ub to promote transfer of the donor Ub from the RING2 active site to the N-terminus of the acceptor Ub (Figure 1). Parkin has also been suggested to bind free Ub. Details about whether parkin binds acceptor or donor Ub and whether Ub binding determines Ub-chain specificity are still unknown.

There is precedence for acceptor Ub binding by HECT E3s and this interaction is essential for chain formation by NEDD4 and its yeast orthologue Rsp5 (Kim et al, 2011; Maspero et al, 2011). In another example, the inactive E2 variant MMS2 binds an acceptor Ub and orients the Ub-Lys63 into the active site of Ubc13 thereby guaranteeing K63-linked chain formation by the E2 (Eddins et al, 2006). Besides proper orientation of the acceptor Ub, chemical differences between α- and ε-amino groups likely contribute to linear Ub-chain specificity. For example, E2s known to be active with RING-type E3s can transfer Ub onto the amino acid lysine, but not the other amino acids containing α-amino groups indicating specificity towards the ε-amino of lysine (Wenzel et al, 2011).

Catalysed by the unexpected discovery that HHARI is a HECT/RING hybrid E3, details about how the RBR class of E3s function are beginning to emerge. We now know, either directly or indirectly, that at least 4 RBR E3s of the 13 identified in humans (HHARI, HOIL, HOIP, and parkin) require a trans-thiolation event using an active site cysteine within RING2. Conservation of this cysteine among all RBR E3s strongly suggests that the RING/HECT-hybrid mechanism is conserved and therefore defines the class. The hybrid mechanism also offers an explanation for the heretofore puzzling observation that, despite being categorized as a RING E3, HOIP determines the type of Ub chain formed. The ability to bind an acceptor Ub close to the RING2 active site likely contributes to how the RBR E3s dictate the type of product they produce. Finally, both HOIP and parkin are auto-inhibited. It remains to be seen whether HOIP’s auto-inhibitory domains work via inhibition of E2∼Ub binding by RING1, obstruction of the active site cysteine on RING2, and/or occlusion of acceptor Ub binding on the LDD (Figure 1). Regardless of the mechanistic details, the ability to modulate their activity may be a common trait of the RBR E3s. Given recent rapid progress, our understanding of this special class of E3s will continue to grow apace.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Chaugule VK, Burchell L, Barber KR, Sidhu A, Leslie SJ, Shaw GS, Walden H (2011) Autoregulation of Parkin activity through its ubiquitin-like domain. EMBO J 30: 2853–2867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen DE, Brzovic PS, Klevit RE (2007) E2-BRCA1 RING interactions dictate synthesis of mono- or specific polyubiquitin chain linkages’. Nat Struct Mol Biol 14: 941–948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddins MJ, Carlile CM, Gomez KM, Pickart CM, Wolberger C (2006) Mms2-Ubc13 covalently bound to ubiquitin reveals the structural basis of linkage-specific polyubiquitin chain formation. Nat Struct Mol Biol 13: 915–920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda F, Deribe YL, Skånland SS, Stieglitz B, Grabbe C, Franz-Wachtel M, van Wijk SJ, Goswami P, Nagy V, Terzic J, Tokunaga F, Androulidaki A, Nakagawa T, Pasparakis M, Iwai K, Sundberg JP, Schaefer L, Rittinger K, Macek B, Dikic I (2011) SHARPIN forms a linear ubiquitin ligase complex regulating NF-κB activity and apoptosis. Nature 31: 637–641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HC, Huibregtse JM (2009) Polyubiquitination by Hect E3s and the determinants of chain type specificity. Mol Cell Biol 29: 3307–3318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HC, Huibregtse JM, Steffen AM, Oldham ML, Chen J (2011) Structure and function of a HECT domain ubiquitin-binding site. EMBO Rep 12: 334–341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirisako T, Kamei K, Murata S, Kato M, Fukumoto H, Kanie M, Sano S, Tokunaga F, Tanaka K, Iwai K (2006) A ubiquitin ligase complex assembles linear polyubiquitin chains. EMBO J 25: 4877–4887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondapalli C, Kazlauskaite A, Zhang N, Woodroof HI, Campbell DG, Gourlay R, Burchell L, Walden H, Macartney TJ, Deak M, Knebel A, Alessi DR, Muqit MM (2012) PINK1 is activated by mitochondrial membrane potential depolarization and stimulates Parkin E3 ligase activity by phosphorylating Serine 65. Open Biol 2: 120080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin I, Eakin C, Blanc M-P, Klevit RE, Miller SI, Brzovic PS (2010) Identification of an unconventional E3 binding surface on the UbcH5∼Ub conjugate recognized by a pathogenic bacterial E3 ligase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 2848–2853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maspero E, Mari S, Valentini E, Musacchio A, Fish A, Pasqualato S, Polo S (2011) Structure of the HECT:ubiquitin complex and its role in ubiquitin chain elongation. EMBO Rep 12: 342–349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smit JJ, Monteferrario D, Noordermeer SM, van Dijk WJ, van der Reijden BA, Sixma TK (2012) The E3 ligase HOIP specifies linear ubiquitin chain assembly through its RING-IBR-RING domain and the unique LDD extension. EMBO J 31: 3833–3844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stieglitz B, Morris-Davies AC, Koliopoulos MG, Christodoulou E, Rittinger K (2012) LUBAC synthesizes linear ubiquitin chains via a thioester intermediate. EMBO Rep 13: 840–846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokunaga F, Sakata S, Saeki Y, Satomi Y, Kirisako T, Kamei K, Nakagawa T, Kato M, Murata S, Yamaoka S, Yamamoto M, Akira S, Takao T, Tanaka K, Iwai K (2009) Involvement of linear polyubiquitylation of NEMO in NF-kappaB activation. Nat Cell Biol 11: 123–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokunaga F, Nakagawa T, Nakahara M, Saeki Y, Taniguchi M, Sakata S, Tanaka K, Nakano H, Iwai K (2011) SHARPIN is a component of the NF-κB-activating linear ubiquitin chain assembly complex. Nature 31: 633–636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel DM, Lissounov A, Brzovic PS, Klevit RE (2011) UBCH7 reactivity profile reveals parkin and HHARI to be RING/HECT hybrids. Nature 474: 105–108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagi H, Ishimoto K, Hiromoto T, Fujita H, Mizushima T, Uekusa Y, Yagi-Utsumi M, Kurimoto E, Noda M, Uchiyama S (2012) A non-canonical UBA-UBL interaction forms the linear-ubiquitin-chain assembly complex. EMBO Rep 13: 462–468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]