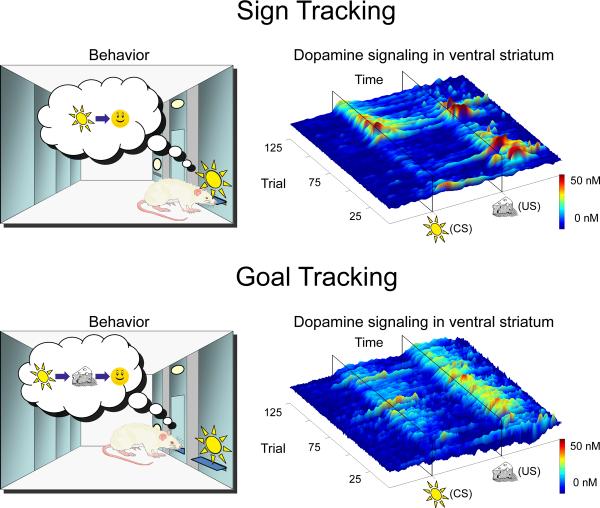

Figure 1. Alternative Pavlovian valuation systems indicated by behavior and corresponding neurotransmission.

When reward-predictive stimuli are spatially displaced from the reward-delivery location, animals can adopt different conditioned responses (left panels). The initial delivery of a primary reward elicits the appropriate unconditioned response such as approach and consumption. After repeated pairing, some animals approach the conditioned stimulus during its presentation (“sign tracking” – top panel; left) whereas others approach the location where the reward will be delivered in the future (“goal tracking” – bottom panel; left). The surface plots depict trial-by-trial fluctuations in dopamine concentration during the twenty-second window around conditioned-stimulus (CS) and unconditioned-stimulus (US) presentation over five days of training (one session per day) in both sign-tracking (top panel; right) and goal-tracking animals (bottom panel; right). Dopamine signaling in sign trackers is consistent with the reporting of a reward prediction error, as US signaling decreases across trials when it becomes predicted, in parallel with the acquisition of approach behavior. However, dopamine signaling in goal-tracking animals is not consistent with the reporting of a reward prediction error, as US signaling is maintained even when approach behavior reaches asymptote. These data are a replication of those reported in reference [34**]. Importantly, the use of selectively bred animals allowed for the demonstration that learning is dopamine dependent in animals where reward prediction errors are encoded but not in animals that lack such encoding [34**]. These findings favor the reward-prediction-error hypothesis of dopamine function in model-free learning.