Abstract

This is a report of 14 patients who suffered from oral cancer and underwent radical excisions of the oral cancer lesion with functional neck dissection at the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery in Annasawmy Mudaliar General Hospital, Bangalore, between 2010 and 2011. Eleven males and 3 females were involved, with the average age of 68.7 years. All patients had positive cervical lymph nodes proven by clinical and ultrasound examination. Level IB was positive in all cases and Level II of the neck was found additionally involved in five cases. A functional neck dissection in patients with a clinically positive node neck achieved better disease-free survival with minimal postoperative co-morbidity.

KEY WORDS: Functional neck dissection, lymph node metastasis, oral cancer

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the most common form of cancer seen in the oral cavity in the Indian subcontinent. More than half the subjects present with lymph node metastases and histological confirmation of metastatic disease is the most important prognostic factor. Neck metastasis is the most important prognostic factor in head and neck SCCs.[1] On account of this widely demonstrated fact, management of neck disease in head and neck cancer has been considered one of the most important aspects of treatment. Nobody can deny the important effect of therapeutic neck dissection in the prognosis of head and neck cancer patients.

Of the head and neck diseases, oral cancer has been the most widely studied tumor as far as neck dissection is concerned. However, the amount and quality of information currently available does not offer a definitive answer to the question of the prognostic effect of elective neck dissection. The ablation of oral SCC involves both local and regional techniques. The goal of surgery is to totally eradicate all visible gross disease as well adequate margins to include suspected microscopic metastasis.[2,3]

Between 90% and 95% of all cases of oral cancer arise from the cells of the oral mucosa.[4] However, the signs and symptoms of oral cancer are relatively easy to see and feel, and easy to watch.[5] The main routes of the cervical lymph node spread are through the first station nodes (Levels I and II) and second station nodes including the Levels III, IV, and V).[6] Predicting the lymphatic spread can help in choosing the appropriate surgical procedure and may also help in predicting the outcome.[7] In the case of the lymph node metastasis, neck dissection should be performed.[8]

The first description of radical neck dissection has traditionally been considered the publication by George Crile in 1906, in his classic paper with 132 patients, with 8% mortality and 3-year survival of 38%.[9] Ward,[10] in 1951, was one of the firsts to suggest the possibility of making a formal selective neck dissection sparing the spinal accessory nerve. At that time, the technique of neck dissection included the en bloc resection of the spinal accessory nerve, the jugular vein, and the sternocleidomastoid muscle, and in some cases, the resection of the vagus nerve. It was Bocca and Pignataro who first described the functional neck dissection or MND III in their landmark paper in 1967. This change of surgical technique had an important relationship with neck dissection because it is intrinsic in the philosophy of a preventive treatment, to make it the less invasive possible without losing oncologic results. In this report, we present the results of the operative treatment of 10 patients with oral cancer treated with functional neck dissection.

Materials and Methods

Between March 2010 and July 2011, 14 patients from the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery in the Annasawmy Mudaliar General Hospital, Bangalore, between 2010 and 2011 underwent primary surgery for the treatment of the oral cavity carcinoma [Figure 1]. Data were recorded according to age, sex, histopathology level grade, and tumor node metastasis (TNM). Preoperative biopsy was done to confirm clinical diagnosis and all tumors were graded as per TNM (AJCC) classification. Ultrasound examination of neck was done to determine the extent of neck metastasis. Distant metastases were excluded by chest radiography and further clinical examination of distant nodal sites. Male:female ratio was 11:3. The patients’ age ranged from 53 to 90 years, with the average of 68.7 years. All the 14 patients underwent functional neck dissection [Figure 2].

Figure 1.

Squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity

Figure 2.

Clinically disease-free neck after functional neck dissection

Results

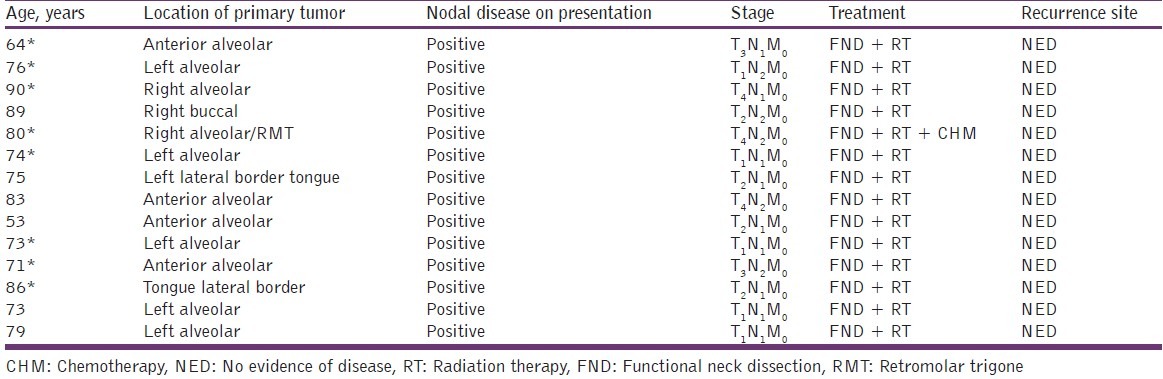

The study group comprised 11 men and 3 women, ranging in age from 53 to 90 years. Data were recorded as shown in Table 1. Postsurgical follow-up ranged from 7 to 45 months (mean 16.58 ± 4.23 months). The mean postsurgical follow-up for was 26.43 ± 5.40 months. At presentation, 20% of the patients with oral SCC harbored cervical nodal disease, as evidenced by either clinical examination or radiographic findings consistent with malignancy. In this series, 42.9% of the patients ultimately demonstrated regional nodal disease attributed directly to the primary tumor.

Table 1.

Patient data: Mandibular, buccal, RMT, and tongue

Histopathologic examination of the excised specimens showed that the most common type of carcinoma was well-differentiated SCC in eight patients and moderately differentiated carcinoma in six patients.

Level II of the neck region was affected (in five patients) and Level IB neck region was affected in all 14 patients. The metastases were not observed in Level III, Level IV, or Level V. None of the patients had a positive resection margin. All respected margins had an average of 2 cm free edges. In all cases, the spinal accessory nerve, internal jugular vein, and sternocleidomastoid muscle were preserved in form and function, and all patients were in good condition with no recurrence. All patients were sent for postoperative radiotherapy with an average of 27 fractionated doses.

Discussion

Carcinoma of the oral cavity has a great potential for metastatic spread to neck lymph nodes, with the incidence reported to be 34-50%.[11] While the importance of treatment of the neck in clinically detected lymph nodes is beyond doubt, elective treatment of the clinically negative neck continues to bring controversy.[12]

Our review of the available literature shows that in all the cases where neck dissection was done, the co-morbidity due to sacrifice of the spinal accessory nerve, internal jugular vein, or the sternocleidomastoid muscle which is always present with a radical neck dissection or modified neck dissection I or II is very high.

In all our cases, the postoperative histopathologic examination showed clear margins to upto 1.4 cm. In all cases, mandibulectomy was done and the mandible resected as part of the primary specimen. None of our patients had any postoperative neurological or functional problems.

Trismus was also absent, and at 1-year postoperative examination after radiation, all patients were disease free [Figure 2]. Even the absence of any reconstruction did not impair their quality of life too much.

Our results found that Level II was the most commonly involved site (63.3%) in the patients with SCC of the oral cavity. Shah had documented similar results.[13]

On the contrary, Byers et al. showed that 16% of patients with oral cancer had metastasis in Level IV without nodes in Levels I, II, or III.[14] Kligerman reported that a total of 67 patients of a group who had undergone resection plus functional neck dissection developed fewer neck recurrences than those on whom resection was performed alone (24% vs. 42%). The disease-free survival rate at 3.5 years in his study for the group treated with the functional neck dissection was 72%, compared with 49% in the group treated with resection alone.[15]

In our study, all patients were treated with functional neck dissection and were disease free at the 1-year postoperative follow-up period.

Low sensitivity and specificity value of ultrasound examination strongly favors functional neck dissection as the only method for clear diagnosis and prediction of the neck metastases in a clinically positive neck.[16]

Conclusion

The role of supraomohyoid neck dissection in the clinically negative neck in the management of early cell carcinoma of the oral cavity remains a controversial subject. The high incidence of occult cervical metastases, poor salvage rates,[17–19] and the increased incidence of extracapsular spread in cases that have developed palpable lymphadenopathy[20] provide a strong argument in favor of a more aggressive treatment of the neck upto removing Level V group of nodes, but the tilt toward functional neck dissection as against radical neck dissection is because of the much lesser co-morbidity in the functional neck dissection as opposed to the radical neck dissection. The role of the functional neck dissection in patients with a clinically positive neck is explored here, but whether this is ideal for the management of cervical node metastasis remains to be proved in prospective multi-institutional trials with a much larger pool of patients.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Mamelle G, Pampurik J, Luboinski B, Lancar R, Lusinchi A, Bosq J. Lymph node prognostic factors in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Am J Surg. 1994;168:494–8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(05)80109-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnes L. Surgical pathology of the head and neck. V. New York: Dekker; 1985. p. 2. (xi, 1866) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gnepp DR. Diagnostic surgical pathology of the head and neck. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2001. p. 11. 888. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goodger NM. Cell cycle regulatory proteins-an overview with relevance to oral cancer. Oral Oncology. 1997;33:61–75. doi: 10.1016/s0964-1955(96)00071-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ackerman IV, Del Regato J. Cancer: Diagnosis, treatment and prognosis. 6th ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alkhalil M, Smajilagić A, Redzić A. The lymph node neck metastasis in oral cancer and elective neck dissection as method of the choice. Medicinski Glasnik. 2007;4:94–6. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Woolgar JA, Scott J. Prediction of cervical lymph node metastasis in squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue/floor of mouth. Head Neck. 1995;17:463–72. doi: 10.1002/hed.2880170603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee JG, Krause CJ. Radical neck dissection: Elective, therapeutic and secondary. Arch Otolaryngol. 1975;101:656–9. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1975.00780400014004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kazi RA. The life and times of George Washington Crile. J Postgrad Med. 2003;49:289–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ward GE, Robben JO. A composite operation for radical neck dissection and removal of cancer of the mouth. Cancer. 1951;4:98–109. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(195101)4:1<98::aid-cncr2820040110>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nithya CS, Pandey M, Naik BR, Mahamed I. Patterns of cervical metastasis from carcinoma of the oral tongue. World J Surg Oncol. 2003;1:1186–96. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-1-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yii NW, Patel SG, Rhys-Evans PH, Breach NM. Management of the N0 neck in early cancer of the oral tongue. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1999;24:75–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2273.1999.00224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shah JP, Candela FC, Poddar AK. The pattern of cervical lymph node metastases from squamous carcinoma of the oral cavity. Cancer. 1990;66:109–13. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19900701)66:1<109::aid-cncr2820660120>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Byers RM, Weber RS, Andrews T, McGill D, Kare R, Wolf P. Frequency and therapeutic implications of “skip metastasis” in the neck from squamous carcinoma of the tongue. Head Neck. 1997;19:14–19. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0347(199701)19:1<14::aid-hed3>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kligerman J, Lima RA, Soares JR. Supraomohyoid neck dissection in the treatment of T1/T2 squamous cell carcinoma of oral cavity. Am J Surg. 1994;168:391–4. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(05)80082-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lydiatt DD, Robbins KT, Byers RM. Treatment of stage I and II oral tongue cancer. Head Neck. 1993;15:308. doi: 10.1002/hed.2880150407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Teichgraeber JF, Clairmont AA. Incidence of occult metastases for cancer of the oral tongue and floor of the mouth, treatment rationale. Head Neck. 1984;7:15–21. doi: 10.1002/hed.2890070105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ho CM, Lam KH, Wei EI. 1992 Occult lymph node metastasis in small oral tongue cancers. Head Neck. 1992;14:359–63. doi: 10.1002/hed.2880140504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Franceschi D, Gupta R, Spiro RH. 1993 Improved survival in the treatment of squamous carcinoma of the oral tongue. Am J Surg. 1993;166:360–5. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(05)80333-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson JT, Barnes L, Myers EN. The extracapsular spread of tumours in cevical node metastasis. Arch Otolaryngol. 1981;107:725–9. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1981.00790480001001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]