Background: The C-terminal domains (CTDs) of NMDA receptors are essential for normal brain function.

Results: We developed kinetic mechanisms for receptors lacking CTDs using single-channel methods.

Conclusion: GluN1 CTDs control primarily unitary conductance and GluN2 CTDs control gating kinetics.

Significance: Results afford quantitative insight into how intracellular perturbations can change the time course of NMDA receptor currents.

Keywords: Gating; Glutamate Receptors Ionotropic (AMPA, NMDA); Ion Channels; Kinetics; Patch Clamp Electrophysiology; Single Molecule Biophysics

Abstract

NMDA receptors (NRs) are glutamate-gated calcium-permeable channels that are essential for normal synaptic transmssion and contribute to neurodegeneration. Tetrameric proteins consist of two obligatory GluN1 (N1) and two GluN2 (N2) subunits, of which GluN2A (2A) and GluN2B (2B) are prevalent in adult brain. The intracellularly located C-terminal domains (CTDs) make a significant portion of mass of the receptors and are essential for plasticity and excitotoxicity, but their functions are incompletely defined. Recent evidence shows that truncation of the N2 CTD alters channel kinetics; however, the mechanism by which this occurs is unclear. Here we recorded activity from individual NRs lacking the CTDs of N1, 2A, or 2B and determined the gating mechanisms of these receptors. Receptors lacking the N1 CTDs had larger unitary conductance and faster deactivation kinetics, receptors lacking the 2A or 2B CTDs had longer openings and longer desensitized intervals, and the first 100 amino acids of the N2 CTD were essential for these changes. In addition, receptors lacking the CTDs of either 2A or 2B maintained isoform-specific kinetic differences and swapping CTDs between 2A and 2B had no effect on single-channel properties. Based on these results, we suggest that perturbations in the CTD can modify the NR-mediated signal in a subunit-dependent manner, in 2A these effects are most likely mediated by membrane-proximal residues, and the isoform-specific biophysical properties conferred by 2A and 2B are CTD-independent. The kinetic mechanisms we developed afford a quantitative approach to understanding how the intracellular domains of NR subunits can modulate the responses of the receptor.

Introduction

NMDA receptors (NRs),2 AMPA receptors, and kainate receptors represent the three glutamate-activated receptors of the ionotropic glutamate receptor (iGluR) family that mediate the vast majority of rapid excitatory synaptic transmission in the mammalian central nervous system (reviewed by Ref. 1). They form tetrameric ion channels with similar overall architecture, consisting of extracellular N-terminal and ligand-binding domains, a transmembrane domain, and an intracellular C-terminal domain (CTD) (2).

Among iGluRs, NRs have several unique features; they are obligate heteromers, have high channel conductance, high Ca2+ permeability, voltage-dependent Mg2+ block, and slow kinetics (3–7). NRs comprise two obligatory GluN1 (N1) subunits, which are ubiquitously expressed from a single gene and two GluN2 (N2) subunits, whose expression from four separate genes (2A–2D) is temporally and specialty regulated (8–16). In adult, the 2A and 2B subunits are the most highly expressed N2 isoforms; however, throughout development 2B dominates early, whereas 2A does so in adulthood. A developmental switch in N2 subtype expression underlies a shift in synaptic plasticity, and this is critically dependent on the CTD (17).

The CTDs act as conduits by which intracellular modulators can alter the NR response. N1 CTDs are comparable in size with those of AMPA and kainate receptors (∼100 amino acids) (18) and are crucial for Ca2+-dependent inactivation of NR currents (19, 20). N2 CTDs are ∼6-fold larger (∼600 amino acids) and are the largest within the iGluR family (18). All iGluR CTDs are predicted to adopt an intrinsically disordered structure (21). Knock-in mice expressing 2A receptors with truncated CTDs survive into adulthood but have synaptic plasticity deficits, whereas those expressing truncated 2B CTDs die perinatally (22–24). These mutant receptors maintain ionotropic functionality and are trafficked to the plasma membrane; however, their synaptic localization is impaired (22, 24–28), suggesting that the deficits arise from insufficient synaptic signaling and/or altered channel gating/modulation. Changes in receptor gating could arise from loss of phosphorylation sites, interaction deficits with intracellular proteins, or changes in structural requisites. Consistent with these possibilities, specific residues within the CTD represent molecular targets for modification by kinase/phosphatase systems (reviewed in Ref. 29) and for binding by cytoplasmic proteins such as calmodulin, α-actinin, and PSD-95 (19, 30, 31).

NRs lacking N2 CTDs produce whole cell responses that are distinct from WT receptors. Specifically, 2A receptors with a truncated CTD exhibit increased macroscopic desensitization (26). Additionally, 2A and 2B receptors lacking CTDs have whole cell responses with lower peak open probability and faster deactivation (28). However, swapping the CTDs of 2A and 2B subunits did not change macroscopic responses, an indication that domains other than the CTDs are responsible for subtype-dependent differences in gating kinetics.

Currently, neither the mechanistic basis for these observed changes in macroscopic behaviors nor the portions of the CTD responsible for influencing the response kinetics are known. To investigate these aspects, we examined single-channel activity recorded from individual NRs that lacked the CTDs of the N1, 2A, and 2B subunits. Based on these results, we conclude that: 1) the CTDs of N1 and N2 subunits influence primarily unitary conductance and receptor gating, respectively; 2) the first 100 amino acids of the N2 CTD control the observed gating effects; and 3) isoform-dependent differences in kinetics and unitary conductance are maintained upon swapping CTDs between 2A and 2B subunits.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cells and Plasmids

Rat GluN1–1a (N1) (U08261), GluN2A (2A) (M91561), or GluN2B (2B) (M91562) were expressed in HEK293 cells along with GFP as previously described (32). Plasmids encoding CTD-truncated GluN1–1a (N1Δ) or GluN2A (2AΔ) were generously provided by G. Westbrook (19, 26). We generated additional truncations by introducing stop codons at residue 845 in GluN2B (2BΔ) and at residue 944 in GluN2A (2AΔ944) with standard molecular biology procedures. Chimeric receptors with CTDs swapped between 2A and 2B subunits were generously provided by M. Constantine-Paton (17). N1/2Ac2B had 1–837 of 2A fused with 839–1483 of 2B; N1/2Bc2A had 1–838 of 2B fused to 838–1465 of 2A. As controls for wild-type N1/2A receptors, we used data files recorded previously in our lab (n = 14) (32), whereas for wild-type N1/2B, we recorded new traces (n = 8) to be consistent with the sampling rate used in this study (40 kHz). Both these data sets were reanalyzed to be consistent with the shorter dead times imposed in this study (0.075 ms).

Electrophysiology

Single-channel currents were recorded continuously from cell-attached patches containing only one active receptor with glass pipettes filled with extracellular solution: 150 mm NaCl, 2.5 mm KCl, 1 mm EDTA, 10 mm HEPBS (pH 8.0 with NaOH) and supplemented with 1 glutamate and 0.1 glycine. Inward Na+ currents were elicited by applying +100 mV through the recording pipette, amplified and low-pass filtered (10 kHz, Axopatch 200B), digitally sampled (40 kHz, National Instruments PCI-6229 A/D board), and stored into digital files (QuB software). For single-channel conductance and reversal potential measurements, we stepped the applied pipette potentials between +100 and +20 mV in 20-mV increments in each patch, at 2-min intervals. Traces were subsequently separated by voltage and analyzed individually with QuB (33).

Whole cell currents were recorded using glass pipettes filled with intracellular solution: 135 mm CsCl, 33 mm CsOH, 2 mm MgCl2, 11 mm EGTA, 1 mm CaCl2, and 10 mm HEPES (pH 7.4 with CsOH). The cells were perfused with extracellular solution: 150 mm NaCl, 2.5 mm KCl, 0.5 mm CaCl2, 0.1 mm glycine, 0.01 mm EDTA, and 10 mm HEPBS (pH 8.0 with NaOH) and were supplemented with glutamate (1 mm) when indicated. The cells were held at −70 mV, and inward Na+ currents were elicited by perfusing the cell with a glutamate-containing extracellular solution. Macroscopic currents were amplified and low pass filtered (2 kHz, Axopatch 200B), sampled (5 kHz, Digidata 1440A), and stored as digital files (pClamp10 software; Molecular Devices).

Excised patch experiments were done with the same solutions used for whole cell experiments. To mimic a synaptic stimulation, solutions with or without glutamate were switched rapidly by moving a double-barrel glass theta tube back and forth across the patch using a piezoelectric translation system (Burleigh LSS-3100/3200) (34). For each patch, open tip potentials were measured at the end of the experiment, and the data were retained for analyses only when the 10–90% solution exchange occurred within 0.15–0.25 ms.

Kinetic Modeling

Selection, processing, idealization, and modeling of single-channel data were done in QuB as described in detail previously (32). Briefly, records were minimally processed to correct for artifacts detected visually and base-line drifts, filtered digitally (12 kHz), and idealized with the SKM algorithm (35). Idealized data in each record contained between 2.5 × 105 and 9 × 106 events. After imposing 0.075 ms as the dead time, these data were fit directly with a MIL algorithm by state models that had increasing numbers of closed and open states (36). Best fitting models were selected with an arbitrarily set threshold for log likelihood improvement of 10 units per added state. Time constants and areas of individual kinetic components, as well as rate constants for the transitions considered in each model, were calculated for each data file and are reported for each data set as the means ± S.E. (supplemental Tables S1 and S2).

To represent the activation reaction of the receptors, we selected events that occurred within bursts by defining a τcrit that misclassified an equal number of events belonging to the E3 and E4 components, as described previously (37). The selected “active” portions were fit by a kinetic model containing three closed and two open states (3C2O). The two open states represented a fast open state (O1), which is common to all gating modes, and a “global” long open state (O2), which represented the average of all long open components occurring in each file. Next, we focused on microscopic desensitization by modeling all events in each data file with a 5C2O model. Rate constants within activation were not different from those obtained by fitting active periods only. In addition, this complete model estimated microscopic desensitization rate constants.

Simulations

Macroscopic responses were simulated in QuB software from 100 channels using the experimentally determined single-channel amplitude of each construct. Traces were computed as the time-dependent accumulation of receptors in the open states using the models indicated, to which we appended two identical glutamate-binding steps. For wild-type 2A receptors, we used values reported previously for the association and dissociation rate constants: 1.7 × 107 m−1 s−1 and 60 s−1, respectively (38). For the simulated traces, we measured the 10–90% rise time and the peak current amplitude (Ipk). Time constants for current decay (τd) and desensitization (τD) were estimated by fitting a single exponential function to the declining portion of the trace.

Statistics

The results are presented as the means ± S.E. for each data set; statistical differences were determined using the Student's t-test and were considered significant for p < 0.05.

RESULTS

CTD Contributions to Channel Conductance

To investigate the role of the large intracellular domain of NRs, we examined the activities of recombinant NRs that lacked the entire CTD modules of N1 (N1Δ), 2A (2AΔ), or 2B (2BΔ) subunits (Fig. 1). WT or CTD-truncated subunits were co-expressed in HEK293 cells in the following combinations: N1Δ/N2, N1/N2Δ, or N1Δ/N2Δ for either 2A or 2B isoforms. For each receptor type we obtained long duration recordings (> 105 events) of steady-state currents from cell-attached membrane patches containing only one active channel (Fig. 2). Inward sodium currents were obtained in the presence of saturating levels of agonists (1 mm glutamate and 0.1 mm glycine) in conditions that minimized inhibitory effects of contaminating divalent ions (1 mm EDTA) (3–6, 39–42) and protons (pH 8.0, 10 mm HEPBS) (43–45).

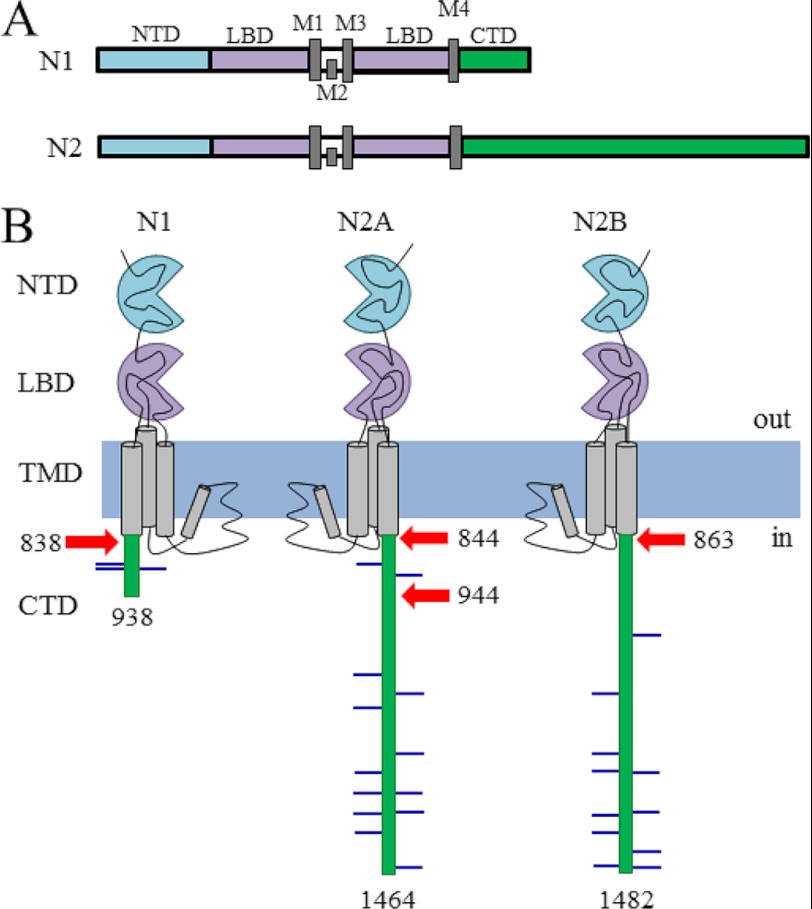

FIGURE 1.

Schematic representation of NR subunits. A, scaled illustration of major functional domains and their respective relative sizes in N1 and N2 subunits. B, cartoon illustrating membrane topology and overall shape for each subunit. Indicated are truncations used in this study (red arrows) and putative phosphorylation sites (lines). NTD, N-terminal domain; LBD, ligand-binding domain.

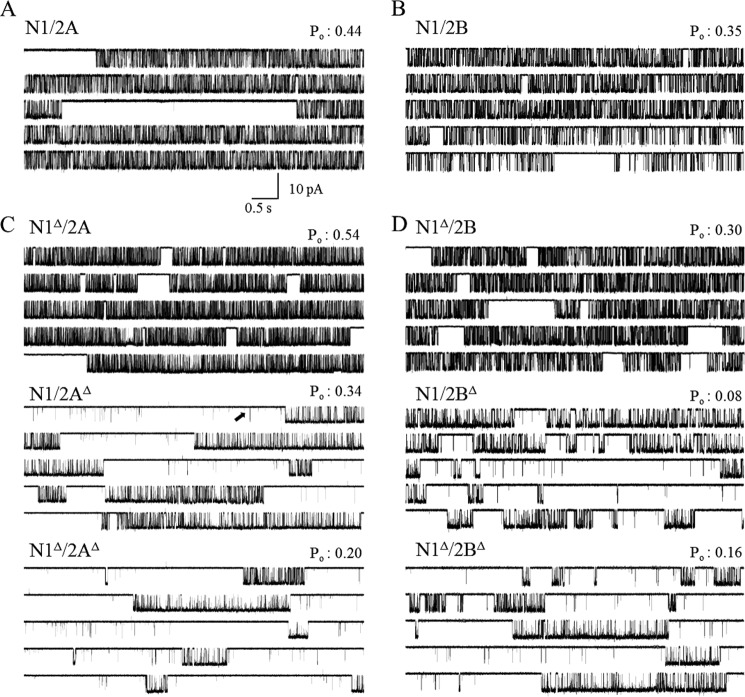

FIGURE 2.

NR single-channel activity. Each panel illustrates a continuous 50-s portion of current recorded from a one-channel HEK293 attached patch expressing wild-type receptors (A) and CTD-truncated receptors (B–D). The Po values indicated in each panel were calculated for the entire file from which the segment was selected. Arrows point to isolated openings that occur only in receptors lacking N2 CTDs.

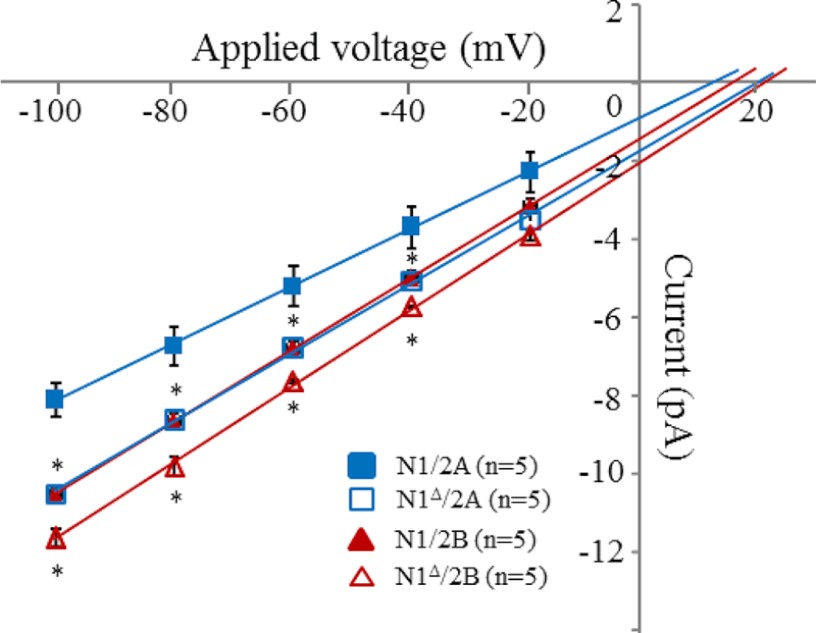

All NRs examined produced unitary currents of uniform amplitudes, with no obvious sublevel or supralevel conductances; currents occurred as bursts of frequent openings separated by long silent periods. In addition to this prevalent bursting behavior, receptors lacking N2 CTDs produced frequently isolated openings (Fig. 2). All events, including these isolated openings, were considered in subsequent analyses. Whether truncated or not, 2B receptors always produced currents with ∼10% larger current amplitudes compared with 2A receptors. Relative to their WT counterpart, 2A and 2B receptors lacking the N1 CTD produced currents with ∼30 and ∼20% larger unitary amplitudes, respectively (Table 1). To test whether these observed changes in unitary current amplitudes reflected greater unitary conductances, we examined the current-voltage relationships for these constructs and estimated their slope conductances (Fig. 3). Both 2A and 2B receptors lacking the N1 CTD had significantly higher single-channel conductance compared with their WT equivalent. Unitary conductance increased from 74 ± 2 to 91 ± 3 pS for N1Δ/2A receptors (p < 0.05) and from 87 ± 2 to 98 ± 3 pS for N1Δ/2B receptors (p < 0.05). All of the receptors tested had similar reversal potential values (Vr = 12–18 mV, p > 0.05), an indication that differences in resting membrane potential between cells did not contribute to the observed changes in unitary current amplitudes.

TABLE 1.

Effects of CTD truncation on global kinetic properties of individual NRs

The values represent the means ± S.E. for each data set.

| Condition | Amplitude | Po | MCT | MOT | Events | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pA | ms | ms | ||||

| N1/2A | 8.7 ± 0.3 | 0.54 ± 0.04 | 4.7 ± 0.5 | 5.4 ± 0.5 | 4.9 × 106 | 14 |

| N1Δ/2A | 11.3 ± 0.4a | 0.54 ± 0.05 | 4.2 ± 0.7 | 4.8 ± 0.5 | 3.3 × 106 | 6 |

| N1/2AΔ | 9.7 ± 0.3 | 0.22 ± 0.04a | 50 ± 10a | 13 ± 2a | 5.0 × 105 | 7 |

| N1Δ/2AΔ | 9.4 ± 0.5 | 0.08 ± 0.02a | 120 ± 20a | 9 ± 1a | 2.0 × 105 | 8 |

| N1/2AΔ944 | 8.6 ± 0.9 | 0.49 ± 0.04 | 5.4 ± 0.3 | 6.0 ± 0.7 | 6.0 × 105 | 6 |

| N1/2B | 10.0 ± 0.4 | 0.33 ± 0.07 | 14 ± 4 | 5.2 ± 0.7 | 2.0 × 106 | 8 |

| N1Δ/2B | 12.3 ± 0.4a | 0.29 ± 0.02 | 13.4 ± 0.9 | 5.6 ± 0.6 | 2.9 × 106 | 6 |

| N1/2BΔ | 10.7 ± 0.3 | 0.12 ± 0.03a | 80 ± 10a | 8.7 ± 0.9a | 5.7 × 105 | 8 |

| N1Δ/2BΔ | 10.5 ± 0.4 | 0.12 ± 0.03a | 100 ± 20a | 11 ± 1a | 5.7 × 105 | 6 |

a Significant difference (lower in bold type and higher in italics) relative to the corresponding wild-type value (p < 0.05).

FIGURE 3.

Current-voltage relationships of single NRs. Amplitudes of single-channel currents recorded from on-cell patches were measured at several applied voltages for receptors lacking the N1 CTD and for wild-type N1/2A and N1/2B. *, significant difference relative to the corresponding wild-type receptor; n = 5 for each condition (p < 0.05).

CTD Contributions to Activation Gating

Next, we used the accumulated single-channel data to estimate channel open probability (Po), mean open time (MOT), and mean closed time (MCT), as global measures of gating kinetics for each receptor. By these metrics, receptors lacking the N1 CTD had WT-like kinetics regardless of the N2 subunit with which they were paired (Table 1). In contrast, receptors lacking the N2 CTD had ∼2-fold lower Po relative to the corresponding WT receptor. For either 2A or 2B, the lower activity was due solely to longer closures (MCT ∼10- or ∼3-fold, respectively) because the openings were also significantly longer in each case (MOT ∼2-fold or ∼1.5-fold, respectively) (Table 1).

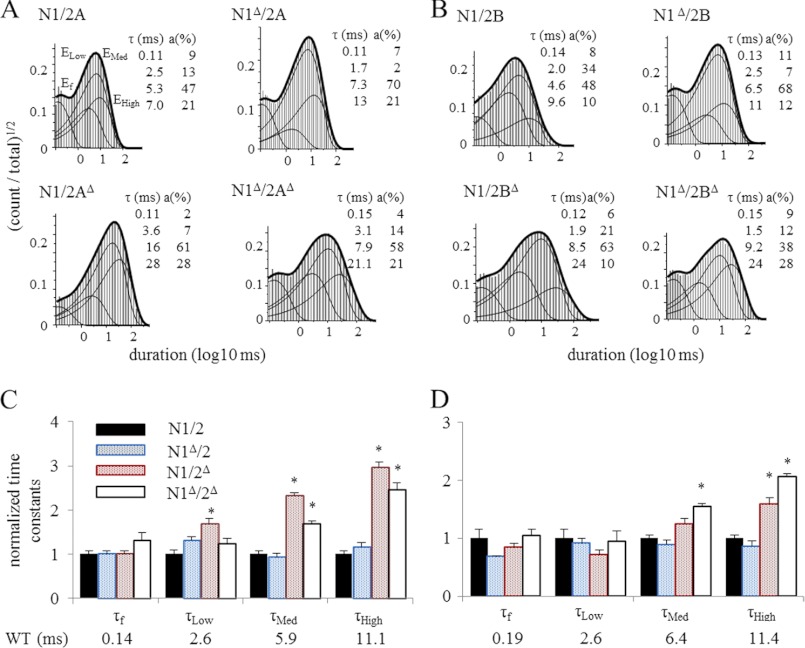

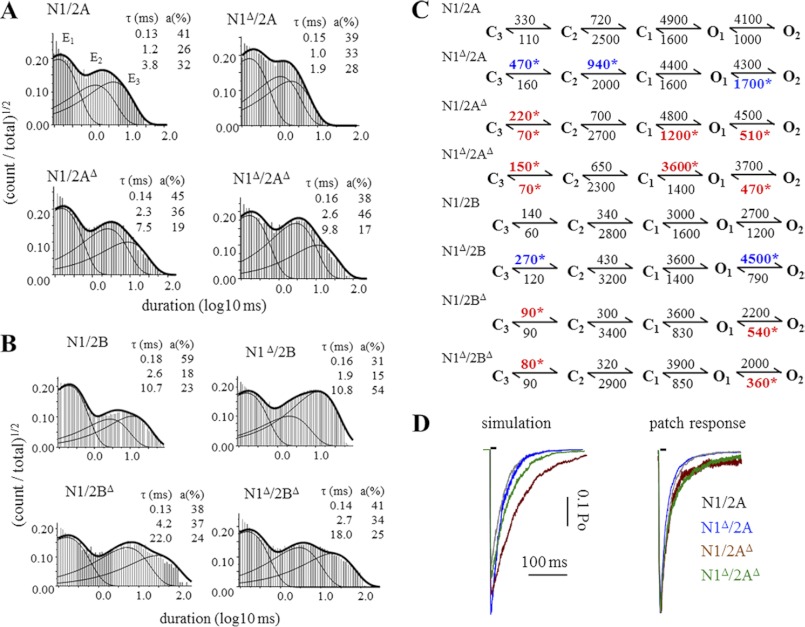

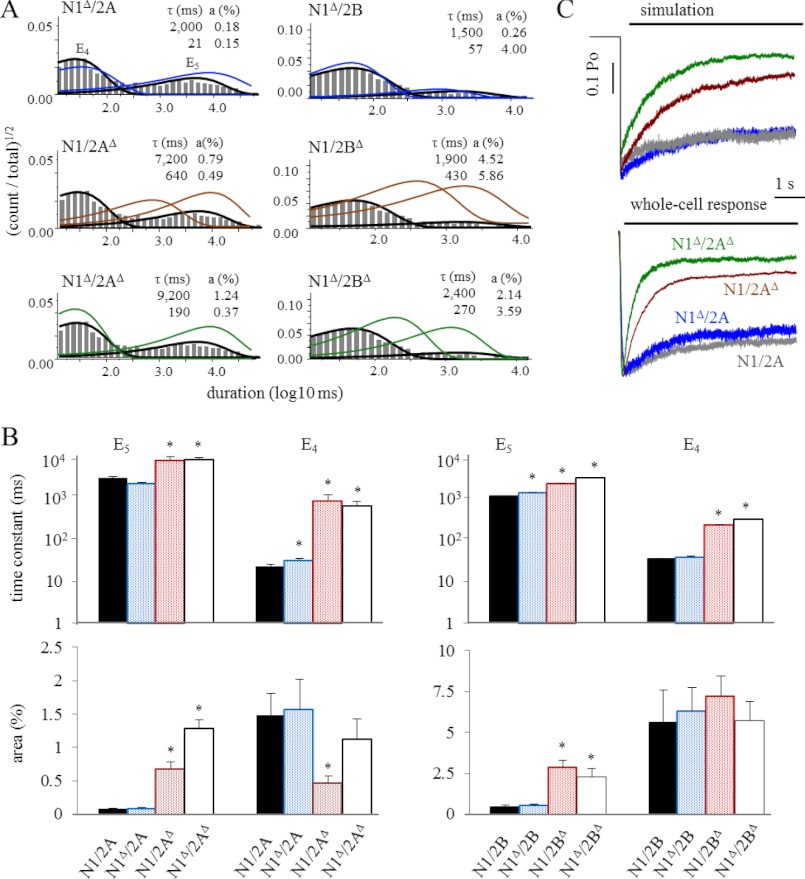

To investigate in further detail how the absence of CTD modules influenced NR gating kinetics, we examined the relative distributions of event durations observed for each receptor type. Previous work established that NRs have complex open and closed event duration distributions. For agonist-bound receptors, closed intervals recorded from WT 2A or 2B receptors have durations that distribute around five components: three shorter components, E1–E3, occur within bursts and make the majority of closed events during brief (1–10 ms) receptor activations (38, 46–48); the two longest components, E4 and E5, occur between bursts and become populated to an observable degree only when receptors are stimulated with longer (>100 ms) agonist pulses (32, 49, 50). Open events have duration distributions that include at least two components: one short and one long when the record examined is kinetically homogeneous, and can have up to four components when the record captures shifts between low, medium, and high kinetic modes, for which the long component adopts mode-specific values (OL, OM, and OH) (47, 51). As observed for WT receptors, all of the constructs investigated in this study produced distributions with five closed and four open components, a clear indication that receptors with truncated CTDs retained the machinery necessary for all gating transitions, including modal shifts. Next, we compared time constants and relative areas of the individual kinetic components.

2A and 2B receptors containing N1Δ had WT-like open distributions consistent with the overall WT-like kinetic parameters reported in Table 1 (supplemental Table S1). For receptors lacking the 2A or 2B CTD, the increases observed in MOTs were entirely explained by across the board increases (1.5–3-fold) in the component durations (Fig. 4), whereas the relative component areas were unchanged (supplemental Table S1). This suggests that the longer MOTs represent changes in the stabilities of open states rather than an alteration in mode distribution (34, 52). In contrast to this generalized effect on open state duration, CTD truncations increased MCTs by increasing preferentially the longer closed intervals, E4 and E5 (supplemental Table S2), an indication that truncated receptors spent more time in desensitized conformations.

FIGURE 4.

Open duration distributions of single NR channels. A and B, histograms of open durations detected in the entire records represented in Fig. 2. Overlaid are probability density functions (thick lines) and individual kinetic components (thin lines) calculated by fitting 5C4O models to each data file. Insets give the calculated time constants (τ) and areas (a) for each open component: Ef, ELow, EMed, and EHigh. C and D, summary bar graphs illustrate the relative changes in the duration of open components. *, statistically significant differences relative to wild type (p < 0.05).

To examine the channels' activation kinetics, we selected from each record the events that occurred within bursts by using a τcrit that excluded closures associated with the long E4 and E5 components (37) (Fig. 5, A and B). Based on the observation that receptors lacking CTD modules maintain WT-like modal behavior, we chose to represent their activations with a simplified kinetic scheme composed of three closed and two open states (47). This model describes the activation reaction as a series of kinetic transitions that start with the first fully liganded closed state C3 and culminates with two coupled open states, O1 and O2. In this model, modal shifts are not incorporated explicitly; rather the O2 state represents globally all long openings observed. Rate constants were estimated for all transitions explicit in the model by fitting the model to the entire sequence of openings and closures within bursts in each record, and values obtained for a particular transition were averaged within each data set. Results showed a complex pattern of changes suggesting that CTDs influenced the receptor activation pathway for all of the combinations tested (Fig. 5C).

FIGURE 5.

Kinetic analyses of activation events. A and B, histograms of closed durations detected within bursts defined with τcrit (see “Experimental Procedures” and text). Overlaid are probability density functions (thick lines) and individual kinetic components (thin lines) calculated by fitting 3C4O models to each active file. Insets give the calculated time constants (τ) and areas (a) for each closed component: E1, E2, and E3. C, state models fitted to the events occurring within bursts in each record. The values on the arrows are the calculated averages, rounded to the first significant figure, for the respective rate constant (s−1). *, rates that were significantly faster (red) or slower (blue) relative to the corresponding wild-type receptor (p < 0.05). D, macroscopic responses to 10-ms applications of 1 mm glutamate were simulated with the models in C (left panel, absolute scale) or recorded experimentally from excised outside-out patches (right panel, normalized to peak current).

We noted that although 2A and 2B receptors containing N1Δ showed overall kinetic parameters that were not significantly different from WT (Po, MOT, and MCT) (Table 1), the modeling results indicated that the activation reaction was significantly faster for both of these receptors. In contrast, all constructs lacking N2 CTDs had slower activation and deactivation rates (Fig. 5C). We used the kinetic models and the measured channel conductances (Table 1) to simulate population responses to brief synaptic-like agonist applications (10 ms, 1 mm). The resulting traces were compared with macroscopic responses recorded from receptors residing in outside-out patches (Fig. 5D). Below, we present the results we obtained for 2A receptors.

Our simulations predicted an increase in peak current for N1Δ/2A and N1/2AΔ relative to WT (20 and 10%, respectively). This prediction is not testable because in outside-out patches, the number of receptors generating the observed currents is variable and unknown. However, we were able to compare the kinetics of simulated and measured traces and observed that receptors lacking CTDs displayed changes in activation and deactivation time course. Specifically, receptors lacking only the N1 CTDs produced currents that decayed faster, whereas receptors lacking 2A CTDs produced currents that were slower to reach peak and also slower to decay (Fig. 5D and Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Effects of CTD truncation on macroscopic activation and deactivation kinetics

The values represent the means ± S.E. for each data set.

| Condition | Rise time | τd |

n | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fast | Slow | |||

| ms | ms | ms | ||

| N1/2A | 5.2 ± 0.4 | 45 ± 4 | 280 ± 40 | 11 |

| N1Δ/2A | 4.9 ± 0.5 | 38 ± 3 | 130 ± 10a | 9 |

| N1/2AΔ | 9 ± 1a | 60 ± 20 | 1500 ± 500a | 6 |

| N1Δ/2AΔ | 13 ± 5a | 70 ± 10a | 500 ± 100a | 5 |

a Significant difference (higher in italics and lower in bold type) relative to the full-length receptor (p < 0.05).

CTD Contributions to Desensitization

To examine the effects of CTD truncations on desensitization kinetics, we compared the time constants and amplitudes of the two longest duration closed components, E4 and E5 (Fig. 6A). Except for N1/2AΔ, which had a smaller area for E4, all truncated receptors had time constants and areas of equal or greater magnitude for these two components (Fig. 6B and supplemental Table S2).

FIGURE 6.

Kinetic analyses of desensitization events. A, histograms of closed durations for events that occurred outside of τcrit defined bursts (see “Experimental Procedures” and text) for WT receptors overlaid with the E4 and E5 components for WT (black lines) or CTD truncated (colored lines) receptors calculated by fitting 5C4O models to entire data files. Insets give the calculated time constants (τ) and areas (a) for the E4 and E5 closed components. B, summary of measured time constants and areas for E4 and E5. *, significant differences relative to wild type (p < 0.05). C, macroscopic responses to 5-s applications of 1 mm glutamate were simulated with the full kinetic models in supplemental Fig. S1 (top panel, absolute scale) or recorded experimentally from whole cells (bottom panel, normalized to peak).

Next, we fit the entire sequence of events observed in each file with a model that, in addition to the 3C2O states that describe the activation sequence, also included two desensitized states, D1 and D2 (supplemental Fig. S1). The estimated rate constants for the 3C2O sequence were not different from those estimated by fitting bursts; in addition, with this procedure we were able to determine microscopic desensitization and resensitization rates. We used the 5C2O models to simulate macroscopic responses to long glutamate pulses (5 s, 1 mm) and compared these responses to currents we recorded experimentally from whole cells exposed to similar stimuli (Fig. 6C).

We observed a close match in the extent of macroscopic desensitization (Iss/Ipk) between the simulated and experimentally measured responses, with receptors containing 2AΔ desensitizing more deeply (smaller Iss/Ipk ratio) (Fig. 6C and Table 3). The macroscopic desensitization time constant of whole cell currents decreased for receptors lacking the 2A CTD and was in fact faster than what was predicted by our results obtained from cell-attached measurements. However, even for WT receptors, macroscopic desensitization was faster in whole cell recordings relative to values expected from cell-attached measurements (32).

TABLE 3.

Effects of CTD truncation on macroscopic desensitization kinetics

The values represent the means ± S.E. for each data set.

| Condition | τD | Iss | Iss/Ipk | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ms | pa | |||

| N1/2A | 1000 ± 100 | 440 ± 60 | 0.67 ± 0.03 | 8 |

| N1Δ/2A | 700 ± 100 | 600 ± 200 | 0.49 ± 0.05a | 10 |

| N1/2AΔ | 630 ± 50a | 210 ± 50a | 0.29 ± 0.02a | 9 |

| N1Δ/2AΔ | 370 ± 20a | 320 ± 40a | 0.23 ± 0.01a | 10 |

a Significant decrease relative to the full length receptor (p < 0.05).

CTD Residues Proximal to the Membrane Control Channel Gating

Given that CTD truncations in N2 subunits produced a much more robust change to gating than in N1, we wondered whether the magnitude of the effect correlates with the conspicuously larger size of N2 CTDs. To investigate this aspect, we introduced a stop codon at residue 944 of 2A (2AΔ944) (Fig. 1B) to produce a CTD of comparable length with that of WT N1 subunits. We co-expressed 2AΔ944 with WT N1, and we recorded on-cell single-channel steady-state currents (data not shown). We were surprised to observe that N1/2AΔ944 currents had Po, MOT, or MCT values similar to those of wild-type N1/2A (Table 1). This result strongly supports the conclusion that, as with N1 subunits, the gating effects of 2A CTDs are largely mediated by membrane proximal residues.

Isoform-specific Gating Kinetics Are Independent of CTDs

We noted that CTD truncations in 2A and 2B subunits affected channel kinetics in a similar manner and that N1/2AΔ and N1/2BΔ receptors retained isoform-specific reaction mechanisms, despite lacking the entire N2 CTDs. Given the well documented differences in kinetics between WT 2A and 2B receptors and the physiologic importance of this difference, we asked whether CTDs of N2 contribute at all to isoform-specific gating. To address this question, we examined the reaction mechanisms of receptors with chimeric N2 subunits: N1/2Ac2B had 2A subunits that contained the CTD of 2B, and N1/2Bc2A had 2B subunits that contained the CTD of 2A (17). N1/2Ac2B receptors produced currents with similar amplitudes and kinetics as N1/2A, whereas N1/2Bc2A receptors produced currents with similar amplitudes and channel kinetics as N1/2B (Table 4). Together, these results indicate that isoform-specific conductance and gating properties of NRs are independent of the N2 CTD modules.

TABLE 4.

Effects of switching CTDs between 2A and 2B subunits

| Condition | Amplitude | Po | MCT | MOT | Events | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pA | ms | ms | ||||

| N1/2A | 9.0 ± 0.6 | 0.64 ± 0.06 | 6 ± 2 | 11 ± 1 | 1.3 × 106 | 5 |

| N1/2Ac2B | 9.7 ± 0.6 | 0.63 ± 0.03 | 5.9 ± 0.6 | 9.5 ± 0.9 | 1.8 × 106 | 9 |

| N1/2B | 10.2 ± 0.4 | 0.21 ± 0.04 | 34 ± 9 | 5.4 ± 0.5 | 2.5 × 106 | 11 |

| N1/2Bc2A | 11.3 ± 0.5 | 0.21 ± 0.05 | 20 ± 3 | 4.2 ± 0.4 | 1.6 × 106 | 7 |

DISCUSSION

The results reported here describe the mechanism by which the N1 and N2 CTDs impact the amplitude and time course of NR responses. We used stationary single-channel recordings and computational methods to delineate the single channel conductance and gating reaction of receptors lacking CTD modules and receptors with swapped C termini, and we validated these results by comparing the predicted macroscopic responses with those measured in whole cell and excised patch preparations. Our results demonstrate the following: 1) N1 CTDs make significant contributions to channel conductance and to macroscopic deactivation kinetics; 2) N2 CTDs control the peak macroscopic current and the kinetics of macroscopic deactivation and desensitization; 3) the first 100 residues of N2 CTDs are mainly responsible for the observed gating effects; and 4) CTDs do not contribute to isoform-specific conductance or gating differences between 2A- and 2B-containing NRs.

We were surprised to note that N1 CTD truncations increased NR single-channel conductance. Among all iGluRs, NRs have the largest single-channel conductance and have remarkably slow kinetics (1). A main function of NRs in synaptic plasticity is to detect coincident pre- and postsynaptic activity and the frequency of presynaptic firing (38, 53) and to respond with large excitatory fluxes, of which calcium represents a significant fraction (54). The molecular determinants and regulatory mechanisms of high NR conductance and calcium permeability are just beginning to be revealed (55, 56). Our results suggest the possibility that perturbations in the N1-CTD modulate NR conductance. Importantly, however, note that in this study we detected channel activity as Na+ fluxes, and thus we have no information regarding possible changes in channel Ca2+ conductance. Also, because in all our single-channel measurements Ca2+ influx was absent and the membrane integrity was preserved, our results lack information regarding Ca2+-dependent modulatory processes.

Previous reports demonstrated that N1 CTDs mediate Ca2+-dependent modulation of NR kinetics. α-Actinin and/or calmodulin modulate single-channel gating of NRs via binding sites located within the N1 CTD (30, 57, 58). These protein-protein interactions, as well as the phosphorylation status of N1 CTD residues, influence Ca2+-dependent inactivation of NR macroscopic currents (19, 20). More specifically, the N1-CTD contains two PKC phosphorylation sites (Ser-890 and Ser-896) and one PKA phosphorylation site (Ser-897) (59). In the cell-attached preparation used here, it is not clear whether these proteins are bound to NRs at basal levels; thus we cannot directly identify whether the loss of either of these interactions is responsible for the changes we observed in receptors lacking N1 CTDs. Our analyses showed no changes in the global single-channel kinetic parameters and only minor changes in the open and closed time distributions for N1Δ/N2 constructs. However, these receptors had faster deactivation rates raising the possibility that protein phosphorylation and/or protein-protein interactions can modulate the NR signal through the N1 CTD. Alternatively, residues in the N1 CTD may be required for the recognition and Ca2+-dependent binding of these proteins, whereas the gating effect may also demand additional interactions with N2 CTDs.

N2 CTDs had the greatest effect on NR gating, and this effect was largely mediated by the membrane proximal segment. Of all iGluR subunits, N2A and N2B have the longest C termini and also have the largest number of post-translational modification sites (1). Consequently, we were not surprised to observe robust changes to NR gating following full truncation of the N2 CTDs. Consistent with previous reports (24, 27, 28), we observed an overall decrease in Po, which, based on our results, we attribute primarily to increased entry into desensitized states. This is an important observation because, in contrast to AMPA-type iGluRs (60), the molecular determinants of NR microscopic desensitization are not known (61). Interestingly, along with the increase in desensitization, there was a simultaneous increase in open durations. In some ion channel families (62–64), phosphorylation/dephosphorylation events are thought to modulate channel Po by controlling transitions between gating modes. In our study, however, following truncation of the N2 CTD, modal transitions were largely intact. This suggests that protein phosphorylation is not responsible for modal shifts in NRs but instead may regulate the lifetime of open conformations in all modes.

An important advance afforded by the work reported here is the delineation of gating mechanisms that account for the entire kinetic repertoire of receptors with CTD perturbations. We used these models to predict in silico macroscopic responses to two physiologically relevant stimulation patterns: brief pulses of glutamate, which reproduce stimuli experienced by synaptic receptors, and seconds-long pulses that reproduce stimuli experienced by extra-synaptic receptors during pathologic conditions (65, 66). The results, which we also validated by measuring responses from excised patch and whole cell preparations, showed that receptors lacking N2 CTDs produced currents with slower deactivation and much deeper desensitization. Similar changes to macroscopic desensitization have been reported previously for receptors with 2A CTD truncations. In these studies, the authors correlated the progression of calcineurin-dependent desensitization with the availability for phosphorylation at position of S900 of 2A (26). Preliminary data from our lab also support a modulatory role for S900; however, this residue is not solely responsible for the observed phenotype of N1/2AΔ,3 suggesting that additional sites along the first 100 residues of the N2 CTD contribute to NR gating.

The structural mechanism by which the N2 CTD exerts its influence on channel kinetics cannot be fully inferred from the data presented in this paper. However, two potential mechanisms are possible: perturbations in the CTD may be transmitted to the desensitization gate through the M4 helix, with which CTD is continuous in sequence; alternatively, such perturbations may be transmitted through putative interactions with the M1-M2 and/or M2-M3 intracellular linkers between helices in the transmembrane domain. Our observation that the membrane proximal segment is critical for the modulatory effects of the N2 CTD is consistent with both of these scenarios.

Our finding that currents produced by N1/2AΔ receptors were slower to reach peak and also slower to deactivate is in contrast with a recent study showing that the current rise time was unchanged and that deactivation time was faster following truncation of the N2 CTD (28). This apparent discrepancy is likely due to differences in experimental conditions as well as differences in Ca2+-dependent inactivation. Specifically, we used the outside-out configuration and a minimal extracellular calcium concentration (0.5 mm), whereas Punnakkal et al. (28) used the lifted whole cell protocol and physiologic calcium concentrations (1.8 mm). Thus, the slower current rise and decay kinetics we observed for N1/2AΔ most likely reflects a change in channel gating rather than a difference in sensitivity to intracellular signaling. Closer examination of Ca2+-dependent changes in channel kinetics will likely provide valuable information regarding intracellular mechanisms of NR modulation.

The effects of N1 CTD truncations on conductance and gating were distinct from those observed for N2 CTD truncations. Thus, regulatory mechanisms mediated through the obligatory N1 subunit are likely applicable to all NRs, whereas those mediated through the differentially expressed N2 subunits may vary across cells, subcellular locations, and developmental stages. This inference is consistent with the idea that N2 subunits, in addition to controlling kinetic differences between NR isoforms, also control sensitivity to intracellular signaling. Specific biochemical pathways, which can execute these modifications, as well as individual residues along the CTDs that can serve as molecular substrates for such proteins, have yet to be determined. Our demonstration that truncation of the CTDs of either 2A or 2B had similar effects on gating and that swapping CTDs of 2A and 2B have no effect on single-channel channel properties suggest that although intracellular mechanisms acting through N2 C termini may be different, the mechanisms through which they affect channel deactivation kinetics and the extent of desensitization are similar. Both these aspects of channel response are of physiologic significance and pharmacologic interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Gary Westbrook for providing CTD truncation constructs for N1 and 2A subunits, Dr. Martha Constantine-Paton for providing chimeras with swapped CTDs and constructs, Tom Ruffino for contributing single-channel recordings, and Eileen Kasperek for molecular biology and tissue culture procedures.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant 052669 through the NINDS. This work was also supported by SUNY REACH.

This article contains supplemental Table S1 and Fig. S1.

R. F. Cole, personal communication.

- NR

- N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor

- iGluR

- ionotropic glutamate receptor

- CTD

- C-terminal domain

- MOT

- mean open time

- MCT

- mean closed time

- HEPBS

- N-(2-Hydroxyethyl)piperazine-N′-(4-butanesulfonic acid).

REFERENCES

- 1. Traynelis S. F., Wollmuth L. P., McBain C. J., Menniti F. S., Vance K. M., Ogden K. K., Hansen K. B., Yuan H., Myers S. J., Dingledine R. (2010) Glutamate receptor ion channels. Structure, regulation, and function. Pharmacol. Rev. 62, 405–496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sobolevsky A. I., Rosconi M. P., Gouaux E. (2009) X-ray structure, symmetry and mechanism of an AMPA-subtype glutamate receptor. Nature 462, 745–756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mayer M. L., Westbrook G. L., Guthrie P. B. (1984) Voltage-dependent block by Mg2+ of NMDA responses in spinal cord neurones. Nature 309, 261–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nowak L., Bregestovski P., Ascher P., Herbet A., Prochiantz A. (1984) Magnesium gates glutamate-activated channels in mouse central neurones. Nature 307, 462–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ascher P., Nowak L. (1988) The role of divalent cations in the N-methyl-d-aspartate responses of mouse central neurones in culture. J. Physiol. 399, 247–266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mayer M. L., Westbrook G. L. (1987) Permeation and block of N-methyl-d-aspartic acid receptor channels by divalent cations in mouse cultured central neurones. J. Physiol. 394, 501–527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lester R. A., Clements J. D., Westbrook G. L., Jahr C. E. (1990) Channel kinetics determine the time course of NMDA receptor-mediated synaptic currents. Nature 346, 565–567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hollmann M., Boulter J., Maron C., Beasley L., Sullivan J., Pecht G., Heinemann S. (1993) Zinc potentiates agonist-induced currents at certain splice variants of the NMDA receptor. Neuron 10, 943–954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Monyer H., Sprengel R., Schoepfer R., Herb A., Higuchi M., Lomeli H., Burnashev N., Sakmann B., Seeburg P. H. (1992) Heteromeric NMDA receptors. Molecular and functional distinction of subtypes. Science 256, 1217–1221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ishii T., Moriyoshi K., Sugihara H., Sakurada K., Kadotani H., Yokoi M., Akazawa C., Shigemoto R., Mizuno N., Masu M. (1993) Molecular characterization of the family of the N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor subunits. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 2836–2843 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Monyer H., Burnashev N., Laurie D. J., Sakmann B., Seeburg P. H. (1994) Developmental and regional expression in the rat brain and functional properties of four NMDA receptors. Neuron 12, 529–540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sheng M., Cummings J., Roldan L. A., Jan Y. N., Jan L. Y. (1994) Changing subunit composition of heteromeric NMDA receptors during development of rat cortex. Nature 368, 144–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Laurie D. J., Seeburg P. H. (1994) Regional and developmental heterogeneity in splicing of the rat brain NMDAR1 mRNA. J. Neurosci. 14, 3180–3194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Laube B., Kuhse J., Betz H. (1998) Evidence for a tetrameric structure of recombinant NMDA receptors. J. Neurosci. 18, 2954–2961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Furukawa H., Singh S. K., Mancusso R., Gouaux E. (2005) Subunit arrangement and function in NMDA receptors. Nature 438, 185–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Behe P., Stern P., Wyllie D. J., Nassar M., Schoepfer R., Colquhoun D. (1995) Determination of NMDA NR1 subunit copy number in recombinant NMDA receptors. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 262, 205–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Foster K. A., McLaughlin N., Edbauer D., Phillips M., Bolton A., Constantine-Paton M., Sheng M. (2010) Distinct roles of NR2A and NR2B cytoplasmic tails in long-term potentiation. J. Neurosci. 30, 2676–2685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ryan T. J., Emes R. D., Grant S. G., Komiyama N. H. (2008) Evolution of NMDA receptor cytoplasmic interaction domains. Implications for organisation of synaptic signalling complexes. BMC Neurosci. 9, 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Krupp J. J., Vissel B., Thomas C. G., Heinemann S. F., Westbrook G. L. (1999) Interactions of calmodulin and α-actinin with the NR1 subunit modulate Ca2+-dependent inactivation of NMDA receptors. J. Neurosci. 19, 1165–1178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhang S., Ehlers M. D., Bernhardt J. P., Su C. T., Huganir R. L. (1998) Calmodulin mediates calcium-dependent inactivation of N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors. Neuron 21, 443–453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Choi U. B., Xiao S., Wollmuth L. P., Bowen M. E. (2011) Effect of Src kinase phosphorylation on disordered C-terminal domain of N-methyl-d-aspartic acid (NMDA) receptor subunit GluN2B protein. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 29904–29912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sprengel R., Suchanek B., Amico C., Brusa R., Burnashev N., Rozov A., Hvalby O., Jensen V., Paulsen O., Andersen P., Kim J. J., Thompson R. F., Sun W., Webster L. C., Grant S. G., Eilers J., Konnerth A., Li J., McNamara J. O., Seeburg P. H. (1998) Importance of the intracellular domain of NR2 subunits for NMDA receptor function in vivo. Cell 92, 279–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Köhr G., Jensen V., Koester H. J., Mihaljevic A. L., Utvik J. K., Kvello A., Ottersen O. P., Seeburg P. H., Sprengel R., Hvalby Ø. (2003) Intracellular domains of NMDA receptor subtypes are determinants for long-term potentiation induction. J. Neurosci. 23, 10791–10799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rossi P., Sola E., Taglietti V., Borchardt T., Steigerwald F., Utvik J. K., Ottersen O. P., Köhr G., D'Angelo E. (2002) NMDA receptor 2 (NR2) C-terminal control of NR open probability regulates synaptic transmission and plasticity at a cerebellar synapse. J. Neurosci. 22, 9687–9697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Steigerwald F., Schulz T. W., Schenker L. T., Kennedy M. B., Seeburg P. H., Köhr G. (2000) C-Terminal truncation of NR2A subunits impairs synaptic but not extrasynaptic localization of NMDA receptors. J. Neurosci. 20, 4573–4581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Krupp J. J., Vissel B., Thomas C. G., Heinemann S. F., Westbrook G. L. (2002) Calcineurin acts via the C-terminus of NR2A to modulate desensitization of NMDA receptors. Neuropharmacology 42, 593–602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mohrmann R., Köhr G., Hatt H., Sprengel R., Gottmann K. (2002) Deletion of the C-terminal domain of the NR2B subunit alters channel properties and synaptic targeting of N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors in nascent neocortical synapses. J. Neurosci. Res. 68, 265–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Punnakkal P., Jendritza P., Köhr G. (2012) Influence of the intracellular GluN2 C-terminal domain on NMDA receptor function. Neuropharmacology 62, 1985–1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chen B., Roche K. (2007) Regulation of NMDA receptors by phosphorylation. Neuropharmacology 62, 471–478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rycroft B. K., Gibb A. J. (2004) Regulation of single NMDA receptor channel activity by α-actinin and calmodulin in rat hippocampal granule cells. J. Physiol. 557, 795–808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lin Y., Skeberdis V. A., Francesconi A., Bennett M. V., Zukin R. S. (2004) Postsynaptic density protein-95 regulates NMDA channel gating and surface expression. J. Neurosci. 24, 10138–10148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kussius C. L., Kaur N., Popescu G. K. (2009) Pregnanolone sulfate promotes desensitization of activated NMDA receptors. J. Neurosci. 29, 6819–6827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Qin F., Auerbach A., Sachs F. (2000) A direct optimization approach to hidden Markov modeling for single channel kinetics. Biophys. J. 79, 1915–1927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Amico-Ruvio S. A., Murthy S. E., Smith T. P., Popescu G. K. (2011) Zinc effects on NMDA receptor gating kinetics. Biophys. J. 100, 1910–1918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Qin F. (2004) Restoration of single-channel currents using the segmental k-means method based on hidden Markov modeling. Biophys. J. 86, 1488–1501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Qin F., Auerbach A., Sachs F. (1997) Maximum likelihood estimation of aggregated Markov processes. Proc. Biol. Sci. 264, 375–383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Magleby K. L., Pallotta B. S. (1983) Burst kinetics of single calcium-activated potassium channels in cultured rat muscle. J. Physiol. 344, 605–623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Popescu G., Robert A., Howe J. R., Auerbach A. (2004) Reaction mechanism determines NMDA receptor response to repetitive stimulation. Nature 430, 790–793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Peters S., Koh J., Choi D. (1987) Zinc selectively blocks the action of N-methyl-d-aspartate on cortical neurons. Science 236, 589–593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Paoletti P., Ascher P., Neyton J. (1997) High-affinity zinc inhibition of NMDA NR1-NR2A receptors. J. Neurosci. 17, 5711–5725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rachline J., Perin-Dureau F., Le Goff A., Neyton J., Paoletti P. (2005) The micromolar zinc-binding domain on the NMDA receptor subunit NR2B. J. Neurosci. 25, 308–317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Forsythe I. D., Westbrook G. L., Mayer M. L. (1988) Modulation of excitatory synaptic transmission by glycine and zinc in cultures of mouse hippocampal neurons. J. Neurosci. 8, 3733–3741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Banke T. G., Dravid S. M., Traynelis S. F. (2005) Protons trap NR1/NR2B NMDA receptors in a nonconducting state. J. Neurosci. 25, 42–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Traynelis S. F., Cull-Candy S. G. (1990) Proton inhibition of N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors in cerebellar neurons. Nature 345, 347–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tang C. M., Dichter M., Morad M. (1990) Modulation of the N-methyl-d-aspartate channel by extracellular H+. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 87, 6445–6449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Banke T. G., Traynelis S. F. (2003) Activation of NR1/NR2B NMDA receptors. Nat. Neurosci. 6, 144–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Popescu G., Auerbach A. (2003) Modal gating of NMDA receptors and the shape of their synaptic response. Nat. Neurosci. 6, 476–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Erreger K., Dravid S. M., Banke T. G., Wyllie D. J., Traynelis S. F. (2005) Subunit-specific gating controls rat NR1/NR2A and NR1/NR2B NMDA channel kinetics and synaptic signalling profiles. J. Physiol. 563, 345–358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Amico-Ruvio S. A., Popescu G. K. (2010) Stationary gating of GluN1/GluN2B receptors in intact membrane patches. Biophys. J. 98, 1160–1169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Dravid S. M., Prakash A., Traynelis S. F. (2008) Activation of recombinant NR1/NR2C NMDA receptors. J. Physiol. 586, 4425–4439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Popescu G. K. (2012) Modes of glutamate receptor gating. J. Physiol. 590, 73–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kussius C. L., Popescu G. K. (2009) Kinetic basis of partial agonism at NMDA receptors. Nat. Neurosci. 12, 1114–1120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Collingridge G. (1987) Synaptic plasticity. The role of NMDA receptors in learning and memory. Nature 330, 604–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Burnashev N., Zhou Z., Neher E., Sakmann B. (1995) Fractional calcium currents through recombinant GluR channels of the NMDA, AMPA and kainate receptor subtypes. J. Physiol. 485, 403–418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Skeberdis V. A., Chevaleyre V., Lau C. G., Goldberg J. H., Pettit D. L., Suadicani S. O., Lin Y., Bennett M. V., Yuste R., Castillo P. E., Zukin R. S. (2006) Protein kinase A regulates calcium permeability of NMDA receptors. Nat. Neurosci. 9, 501–510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. SieglerRetchless B., Gao W., Johnson J. W. (2012) A single GluN2 subunit residue controls NMDA receptor channel properties via intersubunit interaction. Nat. Neurosci. 15, 406–413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Rycroft B. K., Gibb A. J. (2002) Direct effects of calmodulin on NMDA receptor single-channel gating in rat hippocampal granule cells. J. Neurosci. 22, 8860–8868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ehlers M. D., Zhang S., Bernhadt J. P., Huganir R. L. (1996) Inactivation of NMDA receptors by direct interaction of calmodulin with the NR1 subunit. Cell 84, 745–755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Tingley W. G., Ehlers M. D., Kameyama K., Doherty C., Ptak J. B., Riley C. T., Huganir R. L. (1997) Characterization of protein kinase A and protein kinase C phosphorylation of the N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor NR1 subunit using phosphorylation site-specific antibodies. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 5157–5166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Sun Y., Olson R., Horning M., Armstrong N., Mayer M., Gouaux E. (2002) Mechanism of glutamate receptor desensitization. Nature 417, 245–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Borschel W. F., Murthy S. E., Kasperek E. M., Popescu G. K. (2011) NMDA receptor activation requires remodelling of intersubunit contacts within ligand-binding heterodimers. Nat. Commun. 2, 498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Müllner C., Yakubovich D., Dessauer C. W., Platzer D., Schreibmayer W. (2003) Single channel analysis of the regulation of GIRK1/GIRK4 channels by protein phosphorylation. Biophys. J. 84, 1399–1409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Singer-Lahat D., Dascal N., Lotan I. (1999) Modal behavior of the Kv1.1 channel conferred by the Kvβ1.1 subunit and its regulation by dephosphorylation of Kv1.1. Pflügers Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 439, 18–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Groschner K., Schuhmann K., Mieskes G., Baumgartner W., Romanin C. (1996) A type 2A phosphatase-sensitive phosphorylation site controls modal gating of L-type Ca2+ channels in human vascular smooth-muscle cells. Biochem. J. 318, 513–517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Hardingham G. E. (2009) Coupling of the NMDA receptor to neuroprotective and neurodestructive events. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 37, 1147–1160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Clements J. D., Lester R. A., Tong G., Jahr C. E., Westbrook G. L. (1992) The time course of glutamate in the synaptic cleft. Science 258, 1498–1501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]